Abstract

Mutational inactivation of p53 is a hallmark of most human tumors. Loss of p53 function also occurs by overexpression of negative regulators such as MDM2 and MDM4. Deletion of Mdm2 or Mdm4 in mice results in p53-dependent embryo lethality due to constitutive p53 activity. However, Mdm2−/− and Mdm4−/− embryos display divergent phenotypes, suggesting that Mdm2 and Mdm4 exert distinct control over p53. To explore the interaction between Mdm2 and Mdm4 in p53 regulation, we first generated mice and cells that are triple null for p53, Mdm2, and Mdm4. These mice had identical survival curves and tumor spectrum as p53−/− mice, substantiating the principal role of Mdm2 and Mdm4 as negative p53 regulators. We next generated mouse embryo fibroblasts null for p53 with deletions of Mdm2, Mdm4, or both; introduced a retrovirus expressing a temperature-sensitive p53 mutant, p53A135V; and examined p53 stability and activity. In this system, p53 activated distinct target genes, leading to apoptosis in cells lacking Mdm2 and a cell cycle arrest in cells lacking Mdm4. Cells lacking both Mdm2 and Mdm4 had a stable p53 that initiated apoptosis similar to Mdm2-null cells. Additionally, stabilization of p53 in cells lacking Mdm4 with the Mdm2 antagonist nutlin-3 was sufficient to induce a cell death response. These data further differentiate the roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 in the regulation of p53 activities.

Introduction

Proper p53 control is critical for its tumor suppressive function. Under homeostatic conditions, p53 is maintained at low levels by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mdm2, which catalyzes p53 ubiquitination, marking it for degradation by the proteasome (1-3). Mdm2 also binds and inhibits the p53 transcriptional activation domain (4, 5). In response to DNA damage, p53 phosphorylation disrupts Mdm2 binding, leading to p53 stabilization and activation (6). The importance of Mdm2 in p53 regulation was shown in vivo by the lethality of Mdm2−/− embryos at 3.5 days postcoitum whereas p53−/−Mdm2−/− mice develop without abnormalities (7, 8). Mdm2−/− blastocysts undergo spontaneous apoptosis, and reintroduction of p53 into p53−/−Mdm2−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEF) also induces an apoptotic response (9, 10). Similarly, tissue-specific deletion of Mdm2 in cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and the central nervous system results in p53-dependent apoptosis (11-14). Thus, Mdm2 regulation of p53 is essential for proper development, and loss of Mdm2 is sufficient to induce p53-dependent apoptosis in many cell types.

A homologue of Mdm2, Mdm4, also binds the p53 transactivation domain, inhibiting its activity (15). However, the role of Mdm4 in p53 protein stability is murky at best. Overexpression of MDM4 inhibits MDM2-mediated degradation of p53 in immortalized human tumor cell lines, suggesting that MDM4 stabilizes p53 (16-19). Likewise, loss of Mdm4 in MEFs containing a p53 mutant that lacks the proline-rich domain yielded lower p53 levels, albeit a more active p53 (20). In contrast, MEFs lacking Mdm4 contain elevated p53 levels (21, 22). Tissue-specific deletion of Mdm4 in the central nervous system is also associated with increased p53 immunostaining (12, 14). Two other studies showed that MDM4 contributes to MDM2 E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (23, 24). Gu et al. (25) have shown that the MDM2-to-MDM4 ratio may affect p53 stability, providing a possible explanation for these seemingly conflicting results. MDM4 protects p53 from degradation when overexpressed at a ratio greater than 2:1 with respect to MDM2. However, when expressed at similar levels, MDM4 inhibits MDM2 autoubiquitination and enhances MDM2 degradation of p53.

Deletion of Mdm2 or Mdm4 in vivo yields cell lethal phenotypes by different mechanisms (7, 8, 21, 22, 26). As indicated, loss of Mdm2 results in apoptosis in all cells examined to date. Examination of embryos from two Mdm4 mutant lines revealed proliferation defects (22, 26). However, the Mdm4 mutants generated by Migliorini et al. (22) also display apoptosis but only in the developing central nervous system. Conditional deletion of Mdm4 specifically in the central nervous system results in a proliferative defect and apoptosis, whereas cells lacking Mdm2 undergo apoptosis (12, 14). Adult cardiomyocytes lacking Mdm4 also die with time (27). These data suggest that Mdm2 and Mdm4 affect p53 activity differently, resulting in distinct p53 functions in different cell types.

We decided to probe the molecular aspects of this regulation in a different system where we could actually measure p53 half-life. To accomplish this goal, we first asked whether we could generate mice and cells lacking all three genes. Mice lacking p53, Mdm2, and Mdm4 were viable but succumbed to tumorigenesis at a rate similar to that of p53−/− mice. Primary MEFs null for p53 with varying Mdm genotypes were established and infected with a retrovirus encoding a temperature-sensitive p53 mutant. In this system, loss of Mdm2 or Mdm4 led to p53-dependent apoptosis or cell cycle arrest, respectively. In addition, p53 exhibited transcriptional activation of distinct p53 target genes in cells lacking Mdm2 or Mdm4. Analysis of p53 protein half-life revealed that Mdm4 protected p53 from Mdm2-mediated degradation. Understanding the mechanisms by which Mdm2 and Mdm4 regulate p53 is essential to maximize their potential as therapeutic targets for reactivating p53 in tumors.

Results

Mice Lacking p53, Mdm2, and Mdm4 Are Viable

To explore the genetic interaction between Mdm2 and Mdm4 in regulating p53 activity, we attempted to generate mice and cells lacking all three genes. We crossed p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/− and p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/− mice to generate p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− mice. Triple-null mice were viable and born according to the expected Mendelian ratio (Table 1). Moreover, p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− bred well and were subsequently crossed to generate a cohort of triple-null mice. These mice succumbed to tumorigenesis at a rate similar to that of p53−/− mice. Triple-null and p53-null mice had a mean survival of 135 and 140 days, respectively (P = 0.75; Fig. 1A). Triple-null mice also developed mainly thymic lymphomas (67%) and sarcomas (33%), with a few mice presenting with more than one tumor, similar to p53−/− mice (Fig. 1B; Table 2; refs. 28, 29). Thus, the comparable survival and tumor incidence of p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− and p53−/− mice showed that the principal role of Mdm2 and Mdm4 was proper control of p53 activity.

Table 1.

Generation of p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− Mice

| p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/− | × | p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/− | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Expected | Observed (P = 0.78) | |

| p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/− | 6 | 7 | |

| p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/+ | 3 | 3 | |

| p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− | 3 | 2 | |

| p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/− | × | p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− | |

| Genotype | Expected | Observed (P = 0.71) | |

| p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4+/− | 3.5 | 4 | |

| p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− | 3.5 | 3 |

NOTE: Two different crosses were set up to examine the combined effects of Mdm2, Mdm4, and p53 loss on survival. All possible genotypes of progeny are shown. P values were determined by χ2 test.

FIGURE 1.

A. Survival curves of p53−/− (n = 23) and p53−/−Mdm2−/− Mdm4−/− (n = 25) mice as determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis. B. Representative tumors arising in p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− mice. Clockwise from top left corner: lymphoma in the lung, thymic lymphoma, angiosarcoma, and a sarcoma adjacent to a lymphoma in the same mouse.

Table 2.

Tumor Spectrum of p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− Mice

| Tumor Types | Tumor Totals |

|---|---|

| Lymphoma, n (%) | 14 of 21 (67) |

| Sarcoma, n (%) | 7 of 21 (33) |

| Osteosarcoma | 1 |

| Spindle cell | 1 |

| Epithelioid | 1 |

| Angiosarcoma | 2 |

| Unclassified | 2 |

| Total | 21 |

NOTE: n = 19; two animals developed both a lymphoma and sarcoma.

Loss of Mdm2 or Mdm4 Determines p53 Protein Levels

To analyze the effects of Mdm2 and Mdm4 loss on p53 stability and function, we generated isogenic primary MEFs. Because Mdm2−/− and Mdm4−/− embryos are not viable, we isolated fibroblasts from p53−/−Mdm2−/−, p53−/−Mdm4−/−, and p53−/− embryos and infected them with a retrovirus encoding a temperature-sensitive p53 mutant, p53A135V. The cells were maintained and characterized as populations and are hereafter referred to as TSΔ2, TSΔ4, and TS cells, respectively. The p53A135V allele resembles a p53-null allele in vivo (30). In cells, ∼80% of p53A135V resides in the cytoplasm in a nonfunctional conformation at 39°C, whereas at 32°C it migrates to the nucleus and exhibits wild-type conformation and function (31,32). This enabled us to approximate Mdm2−/− and and Mdm4−/− contexts at the permissive temperature of 32°C.

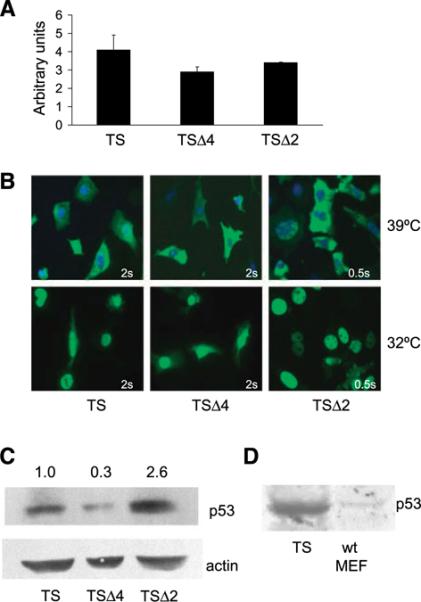

To confirm comparable infection of cells, we measured p53A135V mRNA expression by real-time reverse transcription-PCR in TS, TSΔ2, and TSΔ4 cells. At the nonpermissive temperature, all three cell populations expressed comparable p53A135V mRNA levels and, thus, similar infection efficiency (Fig. 2A). To determine if p53A135V was localized as expected (31), we carried out indirect immunofluorescent staining for p53. At 39°C, p53A135V was predominantly localized in the cytoplasm of TS, TSΔ2, and TSΔ4 cells and relocalized to the nucleus by 6 hours at 32°C (Fig. 2B). p53 was readily detected in TSΔ2 cells with an exposure of 0.5 seconds. However, the levels of p53 were very low in TS and TSΔ4 cells, requiring 2-second exposures. Western blotting confirmed a difference in the steady-state levels of p53A135V protein among cells with different genotypes (Fig. 2C). The level of p53 was 2.6-fold higher in cells lacking Mdm2 than in control cells. Moreover, the level of p53 was distinctly lower in TSΔ4 cells (0.3-fold) than in TS cells. By comparison to endogenous p53 levels in wild-type MEFs, the levels of p53A135V were higher in TS cells (Fig. 2D). Because cell manipulations often lead to activation and stabilization of p53, this system may represent an activated p53. We could not detect endogenous Mdm2 or Mdm4 by Western blot analysis in any of these cell populations.

FIGURE 2.

Endogenous Mdm2 and Mdm4 have distinct effects on steady-state p53 levels. A. Relative p53 mRNA levels of the temperature-sensitive mutant p53A135V were determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR using RNA from TS, TSΔ4, and TSΔ2 cells cultured at the nonpermissive temperature of 39°C and normalized to a Gapdh internal control. SDs were determined from triplicate samples. B. TS, TSΔ4, and TSΔ2 cells were cultured at 39°C or 32°C for 6 h, fixed, and incubated with a p53 primary antibody and a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Exposure times are indicated. C. Immunoblot of p53 from whole-cell lysates prepared from MEFs after culturing at 32°C for 6 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Protein levels were determined by densitometric quantification of immunoblots and relative p53 level is shown. D. A comparison of wild-type (wt) p53 protein levels in MEFs to p53A135V protein levels after retroviral infection of p53-null MEFs by Western blot analysis. Equal amounts of total protein were loaded.

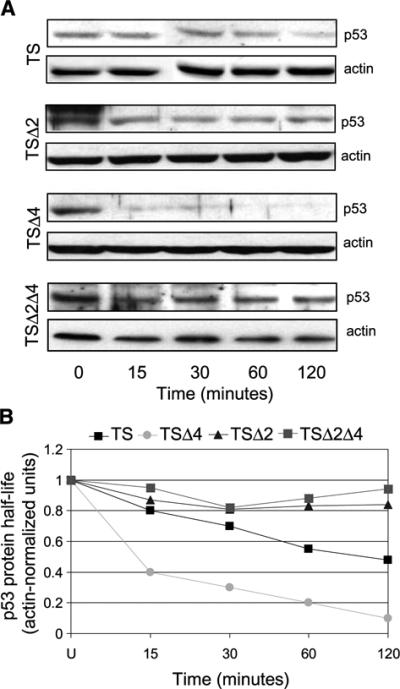

Mdm4 stabilizes p53 presumably by inhibiting p53-Mdm2 interactions because Mdm2 and Mdm4 bind the same domain of p53 (15-19). However, other reports implicate Mdm4 in the down-regulation of p53 protein levels (22, 33). To address the effects of Mdm4 loss on p53 stability, we measured p53A135V protein half-life in TSΔ4 cells. TS, TSΔ2, and TSΔ4 cells were cultured at 32°C for 6 hours to allow for conversion of p53A135V to its wild-type conformation, treated with cycloheximide, and monitored for p53 levels by Western blotting. In control TS cells, p53A135V protein half-life was ∼60 minutes (Fig. 3). In the absence of Mdm2, p53A135V protein levels remained constant throughout the 120-minute time course examined. In contrast, in the absence of Mdm4, p53A135V was quickly degraded and had a half-life of <15 minutes. Thus, the loss of Mdm4 resulted in a decrease in p53A135V steady-state levels and a drastic reduction in p53A135V protein half-life, whereas loss of Mdm2 stabilized p53A135V. We, next introduced p53A135V into p53−/−Mdm2−/−Mdm4−/− (TSΔ2Δ4) MEFs. In these cells, p53A135V was stable throughout the 120-minute time course of cycloheximide treatment, similar to the stability of p53A135V in TSΔ2 cells (Fig. 3). Thus, in the absence of Mdm4, decreased p53A135V stability was due to Mdm2 as deletion of both Mdm2 and Mdm4 resulted in a very stable p53 protein.

FIGURE 3.

Endogenous Mdm2 and Mdm4 have distinct effects on p53 protein stability. A. TS, TSΔ2, TSΔ4, and TSΔ2Δ4 MEFs were cultured at 32°C for 6 h. Cells were then cultured in the presence of cycloheximide for the indicated times. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting with a p53 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. B. p53 half-life was determined by densitometric quantification of the representative immunoblots depicted in A. Cycloheximide experiments were done at least thrice for each cell population.

Loss of Mdm2 or Mdm4 Determines Distinct p53 Phenotypes

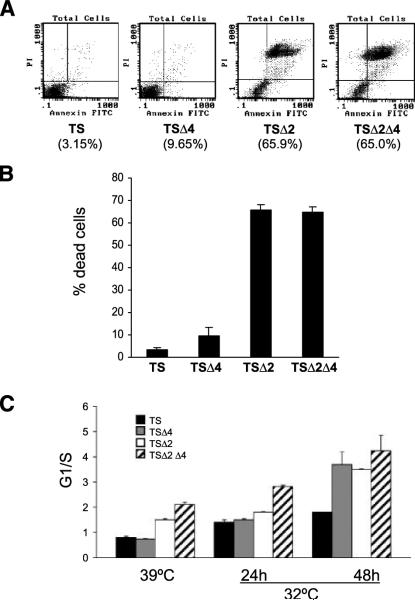

We have previously shown that expression of p53A135V in p53−/−Mdm2−/− MEFs recapitulates the in vivo apoptotic phenotype of Mdm2-null blastocysts (9, 10). Accordingly, we wished to determine if p53A135V expression in TSΔ4 cells could reproduce the proliferation or apoptotic defects seen in Mdm4−/− embryos (9, 22, 26). We therefore analyzed p53 initiation of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis after temperature shift in TS, TSΔ2, TSΔ4, and TSΔ2Δ4 cells. We confirmed apoptosis in TSΔ2 cells by Annexin V labeling, which detects cell membrane disruption, an early hallmark of apoptosis. Sixty-six percent of TSΔ2 cells stained positive for Annexin V 12 hours after temperature shift, whereas TS and TSΔ4 cells exhibited negligible Annexin V-FITC reactivity even after 72 hours at 32°C (Fig. 4A and data not shown). Thus, p53A135V induced apoptosis in the absence of Mdm2, but had little effect in cells lacking Mdm4. We next examined the phenotype of TSΔ2Δ4 cells after temperature shift. Cells lacking Mdm2 and Mdm4 underwent p53-dependent cell death similar to TSΔ2 cells (Fig. 4A and B). Thus, additional loss of Mdm2 in the absence of Mdm4 stabilized p53 and induced an apoptotic response. These data indicated that the dominant phenotype, apoptosis, was due to loss of Mdm2 and was independent of Mdm4.

FIGURE 4.

Mdm2 and Mdm4 determine p53 initiation of cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. A. MEFs were cultured at 32°C for 12 h, labeled with Annexin V-fluorescein and propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine cell viability. Percentages represent apoptotic cells (Annexin V positive). B. Cell viability as determined by positive Annexin V staining described in A. C. The G1-to-S ratio was calculated from cells cultured at 39°C and 32°C and analyzed by flow cytometry. Columns, mean from at least three independent experiments done in duplicate; bars, SE.

We next determined the ratio of G1- to S-phase cells at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. At 39°C, the G1-to-S ratio of TS and TSΔ4 cells was 0.8 whereas that of TSΔ2 cells was 1.5 (Fig. 4C). TSΔ2Δ4 cells had a G1-to-S ratio of 2.1. Temperature shift to 32°C for 24 hours had a small effect on the number of TS, TSΔ2, TSΔ4, and TSΔ2Δ4 cells in G1. However, a pronounced G1 cell cycle arrest was evident at 48 hours in TSΔ4 and TSΔ2 as indicated by their G1-to-S ratios of 3.7 and 3.5, respectively. Similarly, TSΔ2Δ4 cells had a G1-to-S ratio of 4.3. Although TSΔ2 and TSΔ2Δ4 cells exhibited a high G1-to-S ratio at 48 hours at 32°C, this represented a small number of cells because the majority of these cells had already died by apoptosis (Fig. 4A and B). In sum, the predominant phenotype in cells lacking Mdm4 was a G1 cell cycle arrest in response to p53 activation, whereas cells lacking Mdm2, regardless of the Mdm4 genotype, readily underwent apoptosis.

Loss of Mdm2 or Mdm4 Enhances Transcriptional Activity of Distinct p53 Targets

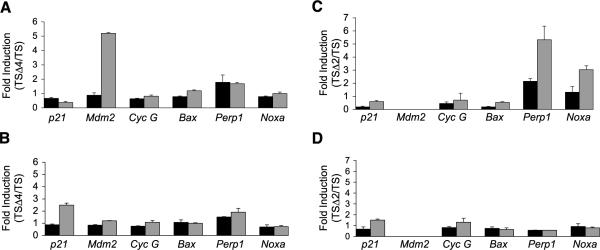

Both Mdm2 and Mdm4 bind the p53 amino terminus, inhibiting its transcriptional activity (15, 34). Although loss of Mdm4 rendered p53 unstable, it still caused a p53-dependent cell cycle arrest likely due to enhanced p53 transcriptional activation. To assess p53 transcriptional activity, we measured induction of endogenous p21, Mdm2, cyclin G, Bax, Perp, and Noxa mRNAs by quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR. TS, TSΔ2, and TSΔ4 cells were cultured at 39°C or 32°C for 6 and 12 hours and then harvested for analysis. Interestingly, TSΔ4 cells exhibited a 5-fold increase in Mdm2 levels over TS cells by 6 hours at 32°C (Fig. 5A). In addition, p21 was induced 2.5-fold by 12 hours after temperature shift (Fig. 5B). However, there was no induction of cyclin G, Bax, Perp, and Noxa in the absence of Mdm4. The gene expression profiles were different in TSΔ2 cells; these cells expressed Perp 3-fold over control cells at 39°C and 6-fold higher after temperature shift for 6 hours (Fig. 5C). Noxa was also expressed 3-fold higher than in controls at 32°C and p21 mRNA levels were slightly elevated over control cells 12 hours after temperature shift (Fig. 5D). Expression of cyclin G and Bax did not change in TSΔ2 cells. These findings indicated that in the absence of Mdm4, p53A135V activated Mdm2 and p21. In contrast, the apoptotic genes Perp and Noxa were preferentially up-regulated in TSΔ2 cells. Our results suggested that Mdm2 and Mdm4 determined initiation of cell cycle arrest or apoptosis by controlling p53 transcriptional activation of distinct target genes.

FIGURE 5.

Transcriptional activation of p53 target genes in TS, TSΔ2, and TSΔ4 MEFs. Fold induction was calculated as gene expression in TSΔ4 cells over TS cells 6 h (A) and 12 h (B) after temperature shift, and in TSΔ2 cells over TS cells 6 h (C) and 12 h (D) after temperature shift. Values were normalized to expression of Gapdh in each reaction. Columns, mean from three independent experiments done in duplicate; bars, SE.

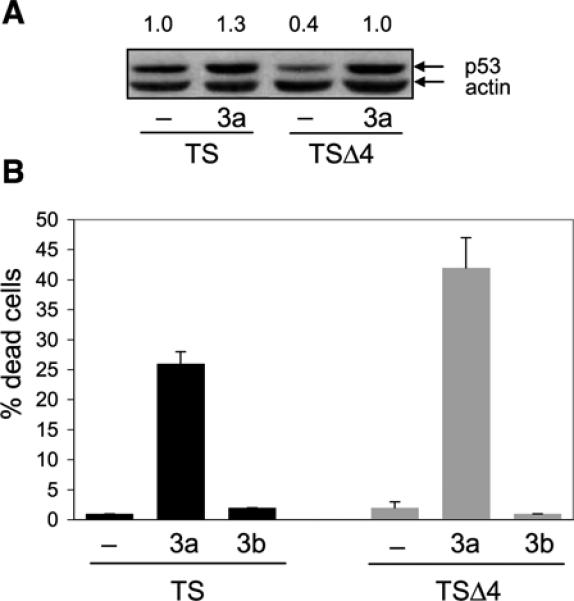

Disruption of Mdm2/p53 Interaction Stabilizes p53 and Initiates Apoptosis in the Absence of Mdm4

Various factors such as the cellular context and p53 protein levels have been shown to influence p53 initiation of a cell cycle arrest or apoptosis (35). Our data suggest that in MEFs, protein levels regulated p53 response. To directly test whether enhanced p53 protein levels were sufficient to induce cell death, we treated TS and TSΔ4 cells with the Mdm2 antagonist nutlin-3 (36). Cells were cultured at 32°C for 4 hours and for an additional 4 hours in the presence of nutlin-3. Treatment with nutlin-3a caused p53A135V stabilization in both TS and TSΔ4 cells (Fig. 6A). In TSΔ4 cells, however, stabilization is specifically due to loss of p53 interactions with Mdm2 because these cells do not have Mdm4. Moreover, nutlin-3a, but not the inactive enantiomer nutlin-3b, reduced the viability of both cell types. Treatment with nutlin-3a caused cell death in ∼28% of TS cells and 42% of TSΔ4 cells at 4 hours (Fig. 6B). Thus, treatment of primary murine fibroblasts with the Mdm2 antagonist nutlin-3a stabilized p53 and was sufficient to induce a cell death response independent of Mdm4.

FIGURE 6.

p53 stabilization induces a cell death response independent of Mdm4. A. TS and TSΔ4 MEFs were cultured at 32°C for 4 h, treated with 50 μmol/L nutlin-3a for 1 h, and analyzed for p53 expression by immunoblotting. Protein levels were determined as in Fig. 1C and relative p53 levels are shown. B. MEFs were cultured at 32°C for 4 h and then treated with 50 μmol/L of nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b for an additional 4 h. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. At least 200 cells were counted for each treatment. Columns, mean from two independent experiments done in duplicate; bars, SE.

Discussion

Knowledge of the mechanisms by which p53 chooses to initiate apoptosis or cell cycle arrest is critical to understanding tumor response on reactivation of p53 (37-39). Clearly, context is important in this decision, but we wanted to further these studies to examine the molecular aspects of this decision. To examine the roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 in this process, we first recapitulated Mdm2−/−, Mdm4−/−, and double-null contexts by expression of a temperature-sensitive p53 protein in primary MEFs. Although various studies have shown that MDM4 overexpression stabilizes p53 in tumor-derived cell lines (16-19, 40), we show that endogenous levels of Mdm4 are sufficient to stabilize p53A135V from Mdm2-mediated degradation because loss of Mdm4 resulted in reduced p53A135V protein half-life. Thus, in these studies, the levels of Mdm4 overwhelm the amount of Mdm2 present in the cell, resulting in p53A135V stabilization. Because Mdm2 and Mdm4 bind the same domain of p53, p53A135V stabilization likely resulted from Mdm4 impeding Mdm2 access to p53A135V (5, 15). Importantly, various studies have shown that Mdm2-Mdm4 interactions also regulate p53 stability and function. In human cells, Mdm4 (also called Hdmx) enhances Mdm2 (also called Hdm2) ligase activity and p53 degradation (40). On the basis of structural analysis, Kostic et al. (41) proposed that Mdm2 and Mdm4 heterodimerization via their respective RING domains contributes to enhanced Mdm2 activity. DNA damage also redirects the ligase activity of Mdm2 from p53 to itself and Mdm4, facilitating p53 activation (42). Therefore, cellular context becomes important as the ratios of Mdm2, Mdm4, and p53 might favor Mdm4-p53, Mdm2-p53, or Mdm4-Mdm2 complexes, resulting in p53 stabilization or degradation. Whereas we know that Mdm2 is transcriptionally regulated by p53, little is known about the transcriptional regulation of Mdm4 (43). Further studies of the interactions of these proteins under specific conditions as well as identification of modifications conducive to particular interactions are needed to further understand the mechanisms of p53 response.

In our studies, a very unstable p53A135V in the absence of Mdm4 retained some transcriptional activity. In TSΔ4 cells, Mdm2 was robustly and rapidly induced by p53A135V after temperature shift, indicating that the initial response to enhanced p53 activity may be to restore physiologic p53 levels. The cell cycle inhibitor p21 was also activated, and these cells exhibited a G1-S arrest. Although MEFs lacking Mdm4 exhibited enhanced p53 activity, these cells did not undergo apoptosis. Under the same conditions, MEFs lacking Mdm2 expressed a stable p53A135V and readily underwent apoptosis at 32°C. Furthermore, cells lacking both Mdm2 and Mdm4 died by apoptosis, suggesting that Mdm2 loss and p53 stabilization are the critical determinants of apoptosis in this system. This idea was further supported by the observation that stabilization of p53A135V on treatment of TS and TSΔ4 cells with the Mdm2 antagonist nutlin-3a also induced a prompt cell death response. Thus, stabilization of p53A135V was associated with the activation of apoptotic target genes and was sufficient to induce apoptosis. The prediction then is that tumors will undergo apoptosis if p53 levels are high enough.

Remarkably, mice lacking p53, Mdm2, and Mdm4 were viable. Furthermore, loss of all three genes did not exacerbate the tumorigenic effect of p53 loss alone, indicating that the primary in vivo role of endogenous Mdm2 and Mdm4 levels was control of p53 activity. Nevertheless, the distinct effects of Mdm4 on p53 stability, activity, and function underscore its potential as another mechanism for inactivating p53 in human tumors (44).

Materials and Methods

Mice and Cell Culture

Generation of Mdm4−/− and Mdm2−/− mice was previously described (8, 26). Mice were crossed with C57BL/6 mice for more than five generations until the background was >90% C57BL/6. MEFs were derived from 13.5-d-old embryos and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotics. 293 Eco Pac packaging cells (Clontech) were maintained per manufacturer's recommendations. Twenty-four hours after plating, packaging cells were transfected with 3 μg of pBabe empty vector or pBabe-p53A135V using Fugene 6 reagent (Roche). For retroviral transduction of MEFs, viral supernatants from 293 cells were applied to early passage (P0-P5) MEFs in the presence of polybrene (4 μg/mL). Infected MEFs were cultured at 39°C for 24 to 48 h to allow for infection, and then media were supplemented with puromycin (2.5 μg/mL) for selection. Confluent puromycin-resistant pools of cells were split into duplicate dishes and either cultured at 32°C or 39°C and harvested for analysis at the indicated times. Infected cells were continuously cultured in the presence of puromycin. For nutlin experiments, 50 μmol/L of nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b (kindly provided by Michael Andreeff, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) was used.

Flow Cytometry and Annexin V Assay

MEFs were harvested by trypsinization, washed in PBS, and then fixed with cold 70% ethanol. On the day of analysis, cells were washed with PBS-T (0.1% Triton X-100), incubated with p53 antibody FL-393 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:400) for 1 h. After washing, cells were incubated with 50 μg/mL propidium iodide in PBS-T (1% Triton X-100) and analyzed by flow cytometry on a Coulter Counter EPICS Profile Analyzer. Annexin V assays were done with an Annexin V-FLUOS kit per manufacturer's recommendations (Roche).

Immunoblotting and Protein Stability

Cells were harvested by scraping in cold PBS and cell pellets were resuspended in 2×SDS loading buffer. Proteins were resolved by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gels, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted with antibodies to p53 (FL-393, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and β-actin (Sigma). To measure protein stability, cells were cultured in the presence of 30 μg/mL cycloheximide (Sigma) for the indicated times and harvested for analysis. Protein levels were quantified by densitometry with a Storm 880 Phosphoimager (Molecular Dynamics).

Immunofluorescent Labeling

Cells were cultured under indicated conditions on coverslips in six-well plates, then washed with PBS and fixed with methanol/acetone (50:50%) for 3 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with p53 antibody (FL-393) for 16 h at 4°C and then incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. Coverslips were then mounted on slides with mounting media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories). Cells were visualized with a Lieca Epifluorescence microscope for the indicated exposure times.

Quantitative Real-time Reverse Transcription-PCR

RNA was extracted from MEFs using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription reactions were done with the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit per manufacturer's recommendation (GE Healthcare). Real-time reverse transcription-PCR was done according to the manufacturer's specification (Applied Biosystems). The Primer Express program was used to design primer sequences that were confirmed for specificity by BLASTN. The following primers were used: Perp, CAGAGCCTCATGGAGTACGC and GAGAATGAAGCAGATGCACAGG. Sequences of p21, Mdm2, cyclin G, Bax, Noxa, and Gapdh primers were previously described (45, 46). Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh expression in each reaction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sohela de Rozieres, Young-Ah Suh, Shunbin Xiong, John Parant, and Sean Post for helpful discussions, and Karen Ramirez for help with flow cytometry.

Grant support: NIH grant CA47296 (G. Lozano) and Cancer Center Support grant CA16672 to M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. J.A. Barboza was supported by Cancer Genetics training grant CA009299.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–9. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:25–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–45. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliner JD, Pietenpol JA, Thiagalingam S, Gyuris J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362:857–60. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shieh SY, Ikeda M, Taya Y, Prives C. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell. 1997;91:325–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones SN, Roe AE, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature. 1995;378:206–8. doi: 10.1038/378206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montes de Oca Luna R, WD, Lozano G. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature. 1995;378:203–6. doi: 10.1038/378203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavez-Reyes A, Parant JM, Amelse LL, de Oca Luna RM, Korsmeyer SJ, Lozano G. Switching mechanisms of cell death in mdm2- and mdm4-null mice by deletion of p53 downstream targets. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8664–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Rozieres S, Maya R, Oren M, Lozano G. The loss of mdm2 induces p53-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene. 2000;19:1691–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boesten LS, Zadelaar SM, De Clercq S, et al. Mdm2, but not Mdm4, protects terminally differentiated smooth muscle cells from p53-mediated caspase-3-independent cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:2089–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francoz S, Froment P, Bogaerts S, et al. Mdm4 and Mdm2 cooperate to inhibit p53 activity in proliferating and quiescent cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3232–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508476103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grier JD, Xiong S, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Parant JM, Lozano G. Tissue-specific differences of p53 inhibition by Mdm2 and Mdm4. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:192–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.192-198.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong S, Van Pelt CS, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Liu G, Lozano G. Synergistic roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 for p53 inhibition in central nervous system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3226–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508500103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shvarts A, Steegenga WT, Riteco N, et al. MDMX: a novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J. 1996;15:5349–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stad R, Ramos YF, Little N, et al. Hdmx stabilizes Mdm2 and p53. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28039–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson MW, Berberich SJ. MdmX protects p53 from Mdm2-mediated degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1001–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.1001-1007.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stad R, Little NA, Xirodimas DP, et al. Mdmx stabilizes p53 and Mdm2 via two distinct mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:1029–34. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp DA, Kratowicz SA, Sank MJ, George DL. Stabilization of the MDM2 oncoprotein by interaction with the structurally related MDMX protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:38189–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marine JC, Francoz S, Maetens M, Wahl G, Toledo F, Lozano G. Keeping p53 in check: essential and synergistic functions of Mdm2 and Mdm4. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:927–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finch RA, Donoviel DB, Potter D, et al. Zhang N. mdmx is a negative regulator of p53 activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3221–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Migliorini D, Lazzerini Denchi E, Danovi D, et al. Mdm4 (Mdmx) regulates p53-induced growth arrest and neuronal cell death during early embryonic mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5527–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5527-5538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poyurovsky MV, Priest C, Kentsis A, et al. The Mdm2 RING domain C-terminus is required for supramolecular assembly and ubiquitin ligase activity. EMBO J. 2007;26:90–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uldrijan S, Pannekoek WJ, Vousden KH. An essential function of the extreme C-terminus of MDM2 can be provided by MDMX. EMBO J. 2007;26:102–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu J, Kawai H, Nie L, et al. Mutual dependence of MDM2 and MDMX in their functional inactivation of p53. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19251–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parant J, Chavez-Reyes A, Little NA, Yan W, Reinke V, Jochemsen AG, Lozano G. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4-null mice by loss of Trp53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate p53. Nat Genet. 2001;29:92–5. doi: 10.1038/ng714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong S, Van Pelt CS, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Fernandez-Garcia B, Lozano G. Loss of Mdm4 results in p53-dependent dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2007;115:2925–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.689901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–21. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nister M, Tang M, Zhang XQ, et al. p53 must be competent for transcriptional regulation to suppress tumor formation. Oncogene. 2005;24:3563–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez J, Georgoff I, Levine AJ. Cellular localization and cell cycle regulation by a temperature-sensitive p53 protein. Genes Dev. 1991;5:151–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michalovitz D, Halevy O, Oren M. Conditional inhibition of transformation and of cell proliferation by a temperature-sensitive mutant of p53. Cell. 1990;62:671–80. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90113-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badciong JC, Haas AL. MdmX is a RING finger ubiquitin ligase capable of synergistically enhancing Mdm2 ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49668–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208593200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bottger V, Bottger A, Garcia-Echeverria C, et al. Comparative study of the p53 − 2 and p53-MDMX interfaces. Oncogene. 1999;18:189–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oren M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:431–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martins CP, Brown-Swigart L, Evan GI. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 2006;127:1323–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, et al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linares LK, Hengstermann A, Ciechanover A, Muller S, Scheffner M. HdmX stimulates Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12009–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2030930100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kostic M, Matt T, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Solution structure of the Hdm2 C2H2C4 RING, a domain critical for ubiquitination of p53. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:433–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang YV, Wade M, Wong E, Li YC, Rodewald LW, Wahl GM. Quantitative analyses reveal the importance of regulated Hdmx degradation for p53 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12365–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701497104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwakuma T, Lozano G. MDM2, an introduction. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:993–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurie NA, Donovan SL, Shih CS, et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature. 2006;444:61–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruins W, Zwart E, Attardi LD, et al. Increased sensitivity to UV radiation in mice with a p53 point mutation at Ser389. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8884–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8884-8894.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu WS, Heinrichs S, Xu D, et al. Slug antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors by repressing puma. Cell. 2005;123:641–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]