Abstract

Autoimmune pathologies are caused by a breakdown in self-tolerance. Tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDC) are a promising immunotherapeutic tool for restoring self-tolerance in an antigen-specific manner. Studies about tolDC have focused largely on generating stable maturation-resistant DC, but few have fully addressed questions about the antigen-presenting and migratory capacities of these cells, prerequisites for successful immunotherapy. Here, we investigated whether human tolDC, generated with dexamethasone and the active form of vitamin D3, maintained their tolerogenic function upon activation with LPS (LPS-tolDC), while acquiring the ability to present exogenous autoantigen and to migrate in response to the CCR7 ligand CCL19. LPS activation led to important changes in the tolDC phenotype and function. LPS-tolDC, but not tolDC, expressed the chemokine receptor CCR7 and migrated in response to CCL19. Furthermore, LPS-tolDC were superior to tolDC in their ability to present type II collagen, a candidate autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. tolDC and LPS-tolDC had low stimulatory capacity for allogeneic, naïve T cells and skewed T cell polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, although LPS-tolDC induced significantly higher levels of IL-10 production by T cells. Our finding that LPS activation is essential for inducing migratory and antigen-presenting activity in tolDC is important for optimizing their therapeutic potential.

Keywords: tolerance, migration, CCR7, naïve T cells, immunotherapy

INTRODUCTION

The optimal treatment for autoimmunity and transplant rejection should be the reinstatement of tolerance in an antigen-specific manner, leaving immunogenic responses to pathogen-derived antigens and cancer immunity intact. One potential immunotherapeutic tool for achieving antigen-specific self-tolerance is tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDC). DC are professional APC, which display inherent plasticity. Thus, depending on their maturation state, they can initiate and modulate immune responses to effector immunity (mature state) or tolerance (immature state) [1,2,3,4].

Numerous studies using rodent models of transplantation and disease have demonstrated that tolDC have great therapeutic potential: They can inhibit rejection and prolong survival of allografts [5,6,7,8,9,10], prevent graft-versus-host disease [11], and inhibit various autoimmune diseases [12,13,14,15,16,17]. We have shown recently that “alternatively activated” DC [DC modulated by dexamethasone (Dex), vitamin D3 (VitD3), and LPS] have regulatory effects on T cells and can migrate in a CCR7-dependent manner [18]. However, we did not address the role that LPS activation played in the induction of these functional characteristics.

Studies about DC vaccines for the induction of cancer immunity have highlighted the fact that DC maturation is essential for effective antigen-specific immunotherapy [19, 20]. Immature DC (immDC) capture and process antigen but do not have the abilities to migrate from peripheral tissues to draining lymph nodes and present the antigen to T cells: DC only acquire these abilities after maturation by inflammatory stimuli, such as LPS.

Although our aim is to induce tolerance and not immunity, it is necessary that tolDC have the abilities to migrate to lymph nodes, process and present the antigen to which tolerance is to be induced, and promote a tolerogenic effect on T cells. There are numerous strategies available to generate stable tolDC in vitro. These include modification of DC with immunological agents, such as IL-10 [21, 22] or vasoactive intestinal peptide [23, 24]; with drugs, such as Dex [25, 26], rapamycin [27, 28], or aspirin [29]; via gene modification, for example, transduction of DC with IL-10 [30, 31] or TGF-β [32, 33]; and through gene silencing using NF-κB decoy oligodeoxyribonucleotides [34, 35] or small interfering RNA [36, 37]. However, most of these strategies impair DC maturation, retaining them in an immature state.

Here, we hypothesize that LPS activation of tolDC is essential for the induction of characteristics necessary for optimal immunotherapeutic potential: the ability to migrate in a CCR7-dependent manner and to present exogenous antigens. We examined the chemokine receptor profiles of tolDC and LPS-activated tolDC and their abilities to migrate in response to the CCR7 ligand CCL19 and to present exogenous autoantigen in the context of MHC class II molecules (MHC II). Importantly, we also tested whether LPS activation of tolDC affected their regulatory activity on naïve T cells. An important finding for the development of tolDC therapies is that LPS activation is essential for the promotion of migratory activity and antigen presentation by tolDC and does not alter their tolerogenic function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of cells from peripheral blood

Human samples were obtained with informed consent after approval by the North Tyneside Research Ethics Committee (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK). PBMC were isolated from fresh blood or buffy coats by density gradient centrifugation on Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield Diagnostics, Dundee, UK). CD14+ monocytes were isolated by positive magnetic selection using anti-CD14 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). CD45RA+/RO– naïve T cells were isolated by negative magnetic selection using RoboSep (StemCell, Vancouver, Canada). The purity of naive T cells was routinely >95%.

Generation of DC populations

Monocytes were cultured at 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in the presence of IL-4 and GM-CSF (50 ng/ml each, Immunotools, Friesoythe, Germany) for 6 days to generate immDC. Medium supplemented with cytokines was refreshed at day 3. tolDC were generated by addition of Dex (10−6 M, Sigma, Poole, UK) at day 3 and Dex plus the active form of VitD3, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (10−10 M, Leo-Pharma, Ballerup, Denmark), at day 6. On day 6, immDC and tolDC were left untreated for another 24 h or were treated with LPS (0.1 μg/ml, Sigma) for 24 h to generate mature DC (matDC) and LPS-tolDC, respectively. All DC populations were washed extensively before using them in functional assays. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

DC cytokine production

DC were washed and stimulated at 1.5 × 105 DC/ml with CD40 ligand (CD40L)-transfected J558L mouse cells (kindly provided by Peter Lane, Birmingham University, UK) at a 1:1 ratio. After 24 h, supernatants were harvested and stored at –20°C. Cytokines (IL-10, TNF-α, and IL-12p70) were quantified using sandwich ELISA (BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry

The following antibodies were used for cell-surface phenotype analysis: CD3-PE (UCHT1), CD4-FITC (RPA-T4), CD40-PE (5C3), CD80-PE (L307.4), and CD86-FITC (2331; all from BD PharMingen); HLA-DR-FITC (B8.12.2; Immunotech, Marseille, France); CD83-FITC (HB15a; Immunotech); and CCR7-allophycocyanin (150503; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). Briefly, cells were centrifuged and resuspended in staining buffer (PBS supplemented with 3% FCS, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.01% sodium azide). Human IgG (Grifols, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was added with antibodies to prevent FcR binding. Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min, centrifuged, and resuspended in staining buffer. To assess IL-10 production, cells were stimulated with T cell CD3/CD28 expander beads (1:1, Dynal, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) for 18 h, and IL-10 secretion was measured using an IL-10 secretion assay (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were also surface-stained for anti-human CD3 and anti-human CD4. Cell viability was assessed using Via-Probe (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were collected on a Beckton Dickinson FACScan and analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA).

Micro Fluidic Cards

RNA was extracted from DC using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using random hexamers and SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen). cDNA samples were run on a custom Micro Fluidic Card (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using an ABI Prism 7900HT system (Applied Biosystems). mRNA expression was normalized to that of human GAPDH by subtracting the comparative threshold (CT) value of the gene of interest from the CT value of the human GAPDH gene (ΔCT). Results are expressed as 2–ΔCT.

DC migration

DC migration was assessed in a transwell system (pore size 8 μm, Corning Life Sciences, UK). DC (2×105; input DC) were added in the upper chamber, and medium, with or without CCL19 (250 ng/ml, R&D Systems), was added to the lower chamber. Migration of DC was assessed after a 2 h incubation period at 37°C by harvesting the DC in the lower chamber and counting using a hemocytometer. DC migration is expressed as the percentage of input DC that had migrated (migration efficiency). To assess whether migration was CCR7-dependent, DC were incubated with 5 μg/ml neutralizing anti-human CCR7 antibody (150503; R&D Systems) or 5 μg/ml matched isotype control (mouse IgG2A: 20102; R&D Systems) for 30 min prior to their addition to the upper chamber of the transwell system.

Antigen-presentation assay

DC were generated from a HLA-DR1+ donor and were loaded with 20 μg/ml human type II collagen (hCII) or 20 μg/ml nonglycosylated peptide pCII259–273 (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) on Day 6 along with the addition of LPS and/or Dex and VitD3. After 24 h, loaded or unloaded DC were harvested and washed thoroughly. DC were incubated with the transgenic murine HLA-DR1-restricted T cell hybridoma, HCII-9.1, at the indicated ratio (see Fig. 4). The T cell hybridoma HCII-9.1 was developed against the nonglycosylated version of the immunodominant T cell epitope of hCII (CII259–273; GIAGFKGEQGPKGET), as described previously [38]. Upon recognition of hCII, the T cell hybridoma secretes IL-2. The IL-2 content of hybridoma supernatants was measured by bioassay as the proliferative response of the cytotoxic T cell line-2 (CTLL-2; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; 3×104/well) during 20 h incubation. CTLL-2 proliferation was assessed by incorporation of 3H-thymidine for the last 18 h of culture by scintillation counting (Microbeta TriLux, Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA).

Fig. 1.

LPS activation induces a semi-mature phenotype in tolDC with retention of an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile. (A) immDC, matDC, tolDC, and LPS-tolDC were stained with antibodies against cell-surface molecules, as indicated, and were assessed by flow cytometry. Debris and dead cells were excluded on the basis of forward-scatter and side-scatter, and viability was detected with Via-Probe. One representative experiment of 12 independent donors is shown. (B) DC populations were washed, cultured at 1.5 × 105 DC/ml, and activated with CD40L-expressing cells (1.5×105/ml) for 24 h. Cytokines in supernatants were quantified by sandwich ELISA. Error bars represent sem of triplicates. One representative experiment of five independent donors is shown. Detection level of IL-12p70 ELISA was 30 pg/ml.

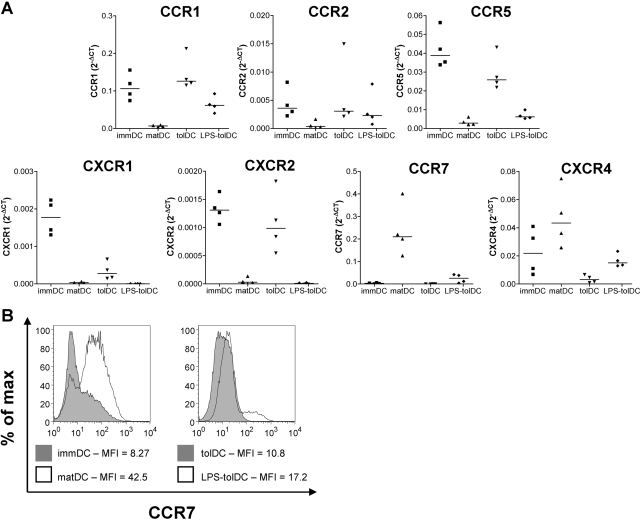

Fig. 2.

tolDC and LPS-tolDC have differential expression of chemokine receptors. (A) Expression of chemokine receptor genes by DC was measured using a custom Micro Fluidic Card (Applied Biosystems). mRNA expression was normalized to that of human GAPDH by subtracting the CT value of the gene of interest from the CT value of the human GAPDH gene (ΔCT). Results are expressed as 2–ΔCT for four independent experiments. Horizontal lines represent median values. (B) DC were harvested 48 h after the addition of LPS and/or Dex and VitD3. DC populations were stained with anti-human CCR7 and were assessed by flow cytometry. Debris and dead cells were excluded on the basis of forward-scatter and side-scatter. The median fluorescent intensity (MFI) is shown. One representative experiment of three independent donors is shown.

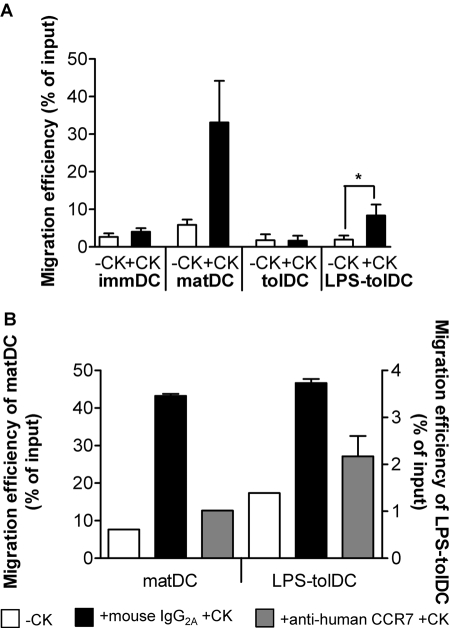

Fig. 3.

LPS activation of tolDC induces migratory activity in response to the CCR7 ligand CCL19. DC populations were left untreated (A) or were treated with 5 μg/ml anti-human CCR7 antibody or mouse IgG2A isotype control for 30 min prior to assessment of migration. (B) Migration of DC was measured over a 2 h period in a transwell system. –CK, No chemokine; +CK, CCL19 (250 ng/ml) in the lower compartment. Migration efficiency was calculated as the percentage of the input DC that had migrated. Data are shown as the mean ± sem of five independent experiments (A) or are representative of three independent experiments; mean ± sem of duplicates are shown (B). * P < 0.05.

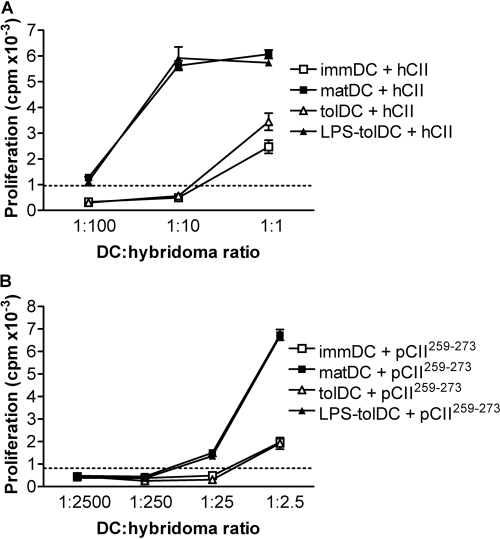

Fig. 4.

LPS activation of tolDC promotes antigen presentation. DC, generated from a HLA-DR1+ donor, were loaded with 20 μg/ml hCII (A) or 20 μg/ml nonglycosylated peptide pCII259–273 (B) on day 6, along with the addition of LPS and/or Dex and VitD3, or were left unloaded. After 24 h, DC were washed and cocultured with the T cell hybridoma HCII-9.1, which is specific for hCII259–273 (ratios are indicated in the figure). IL-2 production by the T cell hybridomas was measured by bioassay as the proliferative response of the IL-2-responsive cell line, CTLL-2. Proliferation was determined during the last 18 h of culture by incorporation of 3H-thymidine. Results are representative of two independent experiments. The dotted line shows the maximum background proliferation induced by unloaded DC. Error bars represent sem of triplicates.

DC-T cell cocultures

DC (1×104) were cultured with 1 × 105 allogeneic, naïve T cells in 200 μl cultures. Supernatants were harvested after 6 days and assayed for IFN-γ by sandwich ELISA (BD PharMingen). Proliferation was determined during the last 18 h of culture by incorporation of 3H-thymidine.

T cell restimulation

Allogeneic, naïve T cells were primed with DC (one DC:10 T cells) for 6 days and rested for 4 days with 0.1 ng/ml recombinant (r)IL-2. Primed T cells were washed and restimulated with matDC from the original DC donor (one DC:10 T cells) or T cell CD3/CD28 expander beads (1:1, Dynal, Invitrogen). No residual DC were observed in the T cell lines. Supernatants were harvested after 72 h and assayed for IL-10 and IFN-γ by sandwich ELISA (BD PharMingen). Cultures were pulsed with 3H-thymidine for a further 8 h to determine proliferation. IL-10 secretion was assessed using an IL-10 secretion assay (Miltenyi Biotec) after 18 h incubation with CD3/CD28 expander beads.

Statistics

Two-tailed paired t-tests were performed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

LPS activation induces a semi-mature phenotype in tolDC with retention of an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile

We first compared the cell-surface phenotype of tolDC and LPS-tolDC (Fig. 1A). tolDC displayed an immature phenotype with moderate levels of HLA-DR and low levels of CD40, the costimulatory molecules CD80/CD86, and the DC maturation marker CD83. Upon LPS activation, tolDC switched to a semi-mature phenotype with high levels of HLA-DR and CD80 and intermediate levels of CD40 and CD86. CD83 was expressed only at a low level by LPS-tolDC. These changes reflect those seen upon maturation of immDC (Fig. 1A).

tolDC and LPS-tolDC had similar anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles upon restimulation with CD40L, although LPS-tolDC produced lower levels of all cytokines measured (Fig. 1B). Compared with matDC, tolDC and LPS-tolDC produced high levels of IL-10 and low levels of IL-12p70. tolDC produced high levels of TNF-α but upon LPS activation levels, reduced to those seen in matDC.

tolDC and LPS-tolDC have different chemokine receptor profiles

As DC function is closely associated with their migratory ability, we measured chemokine receptor expression in the tolDC populations. We found that a number of chemokine receptor genes were expressed differentially by tolDC and LPS-tolDC (Fig. 2A). tolDC expressed chemokine receptors characteristic of an immature phenotype: CCR1, CCR2, CCR5, CXCR1, and CXCR2. LPS activation of tolDC induced a down-regulation of these chemokine receptor genes and an up-regulation of CCR7 and CXCR4, although the levels of expression were lower than in matDC.

To confirm that CCR7 transcripts were translated, we used flow cytometry to assess CCR7 protein expression on the cell surface. CCR7 was up-regulated moderately following LPS activation of tolDC (Fig. 2B), although levels remained lower than on matDC. Together, these data show that tolDC expressed a chemokine receptor profile associated with immDC, whereas LPS-tolDC displayed a profile more consistent with matDC, although to a lower degree (semi-mature phenotype).

LPS activation of tolDC enables them to migrate in response to the CCR7 ligand CCL19

CCR7 directs DC migration to T cell areas in secondary lymph nodes in response to the chemokine CCL19. As tolDC and LPS-tolDC displayed differential expression of CCR7, we assessed the functional capacity of these DC populations to migrate in response to CCL19. As expected, tolDC, which expressed low levels of CCR7 (Fig. 2B), did not migrate in response to CCL19 (Fig. 3A). LPS-tolDC were able to migrate in response to CCL19 (Fig. 3A), consistent with their higher expression of CCR7 (Fig. 2B). Migration of LPS-tolDC and matDC was CCR7-dependent, as neutralization of CCR7 bioactivity resulted in a decrease in migration of DC toward CCL19 (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that activation of tolDC by LPS is vital for the induction of migratory capacity. LPS-tolDC migrated with 25% of the efficiency of matDC in response to CCL19 (Fig. 3A), most likely reflecting their lower levels of CCR7 expression (Fig. 2).

LPS activation of tolDC promotes antigen presentation

To restore self-tolerance efficiently and safely, in vivo tolDC therapy should be tailored toward a specific antigen(s) to avoid inducing nonspecific immunosuppression. To determine the antigen-presenting ability of the various DC populations, we used a hCII-specific murine T cell hybridoma derived from HLA-DR1 transgenic mice, HCII-9.1. In this system, antigen is presented independently of costimulation and cytokine activation, thus the ability to present exogenous antigen is the sole determinant of the response. Similar to immDC, tolDC presented hCII inefficiently (Fig. 4A). As it is not clear if this inefficiency to present antigen reflects reduced antigen processing or reduced antigen presentation by tolDC, we assessed presentation of the nonglycosylated peptide pCII259–273, which is loaded directly onto HLA-DR1 without antigen processing. Similarly to hCII, tolDC presented pCII259–273 inefficiently (Fig. 4B), suggesting a reduced ability to present antigen. LPS activation of tolDC, however, enhanced their ability to present hCII and pCII259–273 to the same level as matDC (Fig. 4). These data suggest that LPS activation of tolDC is essential for efficient antigen presentation in a MHC II-restricted manner.

tolDC and LPS-tolDC have low stimulatory capacity and similar immunomodulatory effects on allogeneic, naïve T cells

In this study, we have shown that LPS activation of tolDC modulates their migratory and antigen-presenting capabilities. To test whether LPS activation of tolDC had an impact on their tolerogenic function, we assessed the T cell-stimulatory capacity of the tolDC populations. Compared with matDC, tolDC and LPS-tolDC had a reduced ability to induce proliferation and IFN-γ production in allogeneic, naïve T cells (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

tolDC and LPS-tolDC have low stimulatory capacity and similar immunomodulatory effects on allogeneic, naïve T cells. (A) matDC, tolDC, or LPS-tolDC (1×104 cells/well) were cocultured with allogeneic, naïve T cells (1×105 cells/well). Proliferation, measured by 3H-thymidine uptake, and IFN-γ production were assessed at day 6. Results are representative of eight independent experiments. Error bars represent sem of triplicates. (B–D) Allogeneic, naïve T cells were primed with DC (one DC:10 T cells) for 6 days and rested for 4 days with 0.1 ng/ml rIL-2. T cell lines primed by matDC (Tmat), tolDC (Ttol), and LPS-tolDC (TLPS-tol) were restimulated with matDC (B) or CD3/CD28 expander beads (C). Proliferation was assessed on day 3 by 3H-thymidine incorporation, and cytokine levels were measured by sandwich ELISA. Results of 10 (B) and 14 (C) independent experiments are shown. Horizontal lines represent mean values. (D) Primed T cells were restimulated with CD3/CD28 expander beads for 18 h, and IL-10 production was assessed using an IL-10 secretion assay. A CD3+CD4+ gate, identifying T cells, was used to exclude DC from subsequent analysis. The cytokine-positive gates shown were determined using unstimulated Tmat, Ttol, and TLPS-tol populations. Results are representative of two independent experiments. IL-10 APC, IL-10 allophycocyanin. (E) The mean production of IL-10 was divided by the mean production of IFN-γ (n=14; data from Fig. 4D), and the ratio was normalized to the IL-10:IFN-γ ratio of Tmat, which was set to 1. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To further investigate the regulatory effects of these tolDC populations on naïve T cell differentiation, primed T cells were recovered from primary DC-T cell cocultures and were restimulated with matDC or CD3/CD28 beads. Upon restimulation, proliferative responses of naïve T cells primed by tolDC (Ttol) and LPS-tolDC (TLPS-tol) were comparable with those of T cells primed by matDC (Tmat), indicating that tolDC subsets had not anergized the T (Ttol) cells (Fig. 5, B and C). However, Ttol and TLPS-tol were skewed toward lower IFN-γ production (Fig. 5B). TLPS-tol produced significantly higher levels of IL-10 than Tmat, and the higher levels produced by Ttol did not reach significance (Fig. 5B). To confirm that the enhanced IL-10 levels in Ttol and TLPS-tol cultures were T cell-derived, cytokines were also measured after restimulation with CD3/CD28 beads in the absence of DC, by ELISA and flow cytometry (Fig. 5, C and D). Under these conditions, Ttol and TLPS-tol produced significantly higher amounts of IL-10 than Tmat (Fig. 5C). The CD4high population displayed in Figure 5D represents the blasting cell population, whereas the CD4low population corresponds to the nonblasting cell population (data not shown). It should be noted that TLPS-tol also secreted significantly higher amounts of IFN-γ than Ttol but that the IL-10/IFN-γ ratios of these T cell populations were similarly enhanced compared with Tmat (Fig. 5E).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates for the first time that LPS activation of human tolDC, generated with Dex and VitD3, is essential for efficient induction of CCR7-directed migration and antigen presentation. We found that LPS activation of tolDC induced a semi-mature phenotype, including up-regulated CCR7 expression, while leaving the anti-inflammatory cytokine profile unaffected. Compared with unactivated tolDC, LPS-tolDC displayed increased migratory activity in response to the CCR7 ligand CCL19 and enhanced ability to present the candidate autoantigen hCII. Importantly, activation of tolDC with LPS did not alter their regulatory action: tolDC and LPS-tolDC skewed naïve T cell differentiation toward an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile.

The maturation state of DC has been shown previously to be an important determinant for the efficacy of DC-based immunotherapy in cancer [19, 20]. DC maturation stimuli, such as LPS, enhance the antigen-presenting ability and migratory activity of DC, both of which are required for the induction of effective immunity [39,40,41,42]. Studies in the tolerance field have focused largely on DC that are resistant to maturation stimuli, such as DC that have been treated with the immunosuppressive drugs Dex and VitD3. Both of these drugs have inhibitory effects on DC maturation by down-regulating components of the NF-κB signaling pathway [43, 44]. Treatment of human monocyte-derived DC with Dex and/or VitD3 leads to reduced expression of costimulatory molecules and inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production [18, 43, 45,46,47,48,49,50], making these tolDC ideal candidates for the induction of tolerance. However, the abilities to present autoantigens on MHC II and to migrate in a CCR7-dependent manner are also critical for successful therapy with tolDC. The question of how these capabilities can be enhanced in tolDC while retaining their tolerogenic capacity is therefore important and has not been formally addressed by previous studies.

The DC chemokine receptor profile determines, to a large extent, their migratory capacity and is associated with their maturation state [51]. Upon antigen uptake and maturation, DC down-regulate chemokine receptors involved in recruitment to and retention in peripheral tissue and up-regulate expression of CCR7 and CXCR4 [52]. CCR7 is particularly important, as it binds the chemokines CCL19 and CCL21, which direct the DC to draining lymph nodes, facilitating interactions with T cells and induction of immunity. Interestingly, it has been shown that CCR7 is also required for the induction of tolerance and it is thought that CCR7-dependent migration of tolDC plays a pivotal role in this respect [53, 54].

The chemokine receptor profile of our human monocyte-derived tolDC, generated with Dex and VitD3, is similar to those in an immature state, and this is reflected by their inability to migrate in response to CCL19. Using these tolDC for therapy would most likely be ineffective, as the tolDC would be unable to migrate from the site of injection to draining lymph nodes and would therefore be unable to tolerize naïve T cells. We have demonstrated that our tolDC acquire the ability to migrate in response to CCL19 after LPS activation. Our results are similar to a previous murine tolDC study showing that bone marrow-derived DC, genetically modified to express the soluble TNF-α receptor (TNFR) and stimulated with LPS, have the ability to migrate in vitro in response to CCL19, although with lower efficiency than mature DC [55]. It was not clear from that study whether their tolDC migration required LPS activation, however, as unactivated tolDC were not tested. In contrast, our findings are dissimilar to another study demonstrating the inability of migration of a murine DC cell line treated with Dex and LPS [56]. The differences in DC source (human monocyte-derived vs. murine bone marrow-derived vs. murine DC cell line), treatment regimes (Dex/VitD3 vs. TNFR vs. Dex), and migration read-outs (in vitro vs. in vivo) make it difficult to compare these studies but emphasize the need to assess the migratory ability for every type of tolDC prior to clinical application.

Another requirement for successful tolDC therapy, particularly in autoimmune diseases, is the ability of tolDC to present autoantigen(s) on MHC II, but most studies on tolDC therapy have not addressed this issue. Although peptide loading could be considered for autoantigens, where the immunodominant epitope(s) and the patient’s MHC haplotype are known, this is not always the case nor practical, and loading with whole protein antigens may be the preferred option. Here, we demonstrate that LPS activation of tolDC is required for efficient antigen presentation of a candidate autoantigen to levels comparable with matDC. In apparent contrast to our data, two previous studies using human monocyte-derived DC treated with Dex or VitD3 showed that these tolDC displayed low efficiency in presenting tetanus toxoid (TT) to autologous T cell lines, even after treatment with a DC maturation stimulus [45, 48]. However, whether the low stimulation of TT-specific T cells in these studies was due to a low antigen presentation capacity per se or to other features of tolDC (e.g., lack or low expression of costimulatory molecules, low production of proinflammatory cytokines, or expression of inhibitory molecules) cannot be distinguished. Our antigen-presentation model using T cell hybridomas generated from human HLA-DR1 transgenic mice that recognize hCII in a DR1-restricted manner [38, 57] is independent of costimulation and DC cytokine production and is therefore a useful tool to assess the antigen-presenting capacity of tolDC.

The importance of LPS activation for effective tolDC therapy in vivo has been demonstrated in a murine model of transplantation [58]. tolDC generated with Dex and LPS but not those generated with Dex alone prolonged the survival of a fully MHC-mismatched heart allograft. The reason why LPS activation of Dex-treated tolDC was required for tolerance induction in vivo was unclear, but our data provide a possible explanation. This would be consistent with another in vivo study, which demonstrated that CCR7 expression by DC transduced with viral IL-10 was essential for the prolongation of cardiac allograft survival in a murine model [53].

Importantly, we have shown that LPS activation of tolDC improves their ability to present exogenous antigen without diminishing their tolerogenic function. tolDC and LPS-tolDC had a reduced ability to stimulate allogeneic, naïve T cells as compared with mature DC. Although the T cells were not anergized, their responses were skewed toward higher IL-10 and lower IFN-γ production upon restimulation. Immune deviation of T cells from a harmful proinflammatory to a protective, anti-inflammatory cytokine profile may be beneficial for the treatment of a variety of diseases, including various autoimmune disorders [59, 60] and allograft rejection [61].

In conclusion, LPS activation of tolDC is required for the acquisition of migratory activity and enhancement of exogenous antigen presentation but does not affect their tolerogenic function. Migratory capacity and antigen-presenting ability will be essential for the induction of safe, effective antigen-specific T cell tolerization in vivo. These findings are important for optimizing the therapeutic potential of tolDC for the use in diseases such as autoimmunity.

Acknowledgments

The Arthritis Research Campaign (grant No. 17750) funded this work. We thank Dr. Simi Ali for helpful advice about the migration assay.

References

- Lutz M B, Schuler G. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahnke K, Schmitt E, Bonifaz L, Enk A H, Jonuleit H. Immature, but not inactive: the tolerogenic function of immature dendritic cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:477–483. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R M, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig M C. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M. Dendritic cells in immunity and tolerance—do they display opposite functions? Immunity. 2003;19:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczynski R M, Bransom J, Cattral M, Huang X, Lei J, Xiaorong L, Min W P, Wan Y, Gauldie J. Synergy in induction of increased renal allograft survival after portal vein infusion of dendritic cells transduced to express TGFβ and IL-10, along with administration of CHO cells expressing the regulatory molecule OX-2. Clin Immunol. 2000;95:182–189. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Wang Q, Liu Y, Sun Y, Ding G, Fu Z, Min Z, Zhu Y, Cao X. Effective induction of immune tolerance by portal venous infusion with IL-10 gene-modified immature dendritic cells leading to prolongation of allograft survival. J Mol Med. 2004;82:240–249. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Wei M F, Liu F, Shi H F, Wang G. Interleukin-10 modified dendritic cells induce allo-hyporesponsiveness and prolong small intestine allograft survival. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2509–2512. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M Q, Suo Y P, Gong J P, Zhang M M, Yan L N. Augmented regeneration of partial liver allograft induced by nuclear factor-κB decoy oligodeoxynucleotides-modified dendritic cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:573–578. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i4.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Hou L, Qiao H, Pan S, Zhou B, Liu C, Sun X. Administration of tolerogenic dendritic cells induced by interleukin-10 prolongs rat splenic allograft survival. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:3255–3259. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taner T, Hackstein H, Wang Z, Morelli A E, Thomson A W. Rapamycin-treated, alloantigen-pulsed host dendritic cells induce Ag-specific T cell regulation and prolong graft survival. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:228–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorny A, Gonzalez-Rey E, Fernandez-Martin A, Ganea D, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide induces regulatory dendritic cells that prevent acute graft-versus-host disease while maintaining the graft-versus-tumor response. Blood. 2006;107:3787–3794. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S H, Kim S, Evans C H, Ghivizzani S C, Oligino T, Robbins P D. Effective treatment of established murine collagen-induced arthritis by systemic administration of dendritic cells genetically modified to express IL-4. J Immunol. 2001;166:3499–3505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y, Yang J, Gupta R, Shimizu K, Shelden E A, Endres J, Mule J J, McDonagh K T, Fox D A. Dendritic cells genetically engineered to express IL-4 inhibit murine collagen-induced arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1275–1284. doi: 10.1172/JCI11490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Duivenvoorde L M, Louis-Plence P, Apparailly F, van der Voort E I, Huizinga T W, Jorgensen C, Toes R E. Antigen-specific immunomodulation of collagen-induced arthritis with tumor necrosis factor-stimulated dendritic cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3354–3364. doi: 10.1002/art.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges M, Rossner S, Voigtlander C, Schindler H, Kukutsch N A, Bogdan C, Erb K, Schuler G, Lutz M B. Repetitive injections of dendritic cells matured with tumor necrosis factor α induce antigen-specific protection of mice from autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2002;195:15–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verginis P, Li H S, Carayanniotis G. Tolerogenic semimature dendritic cells suppress experimental autoimmune thyroiditis by activation of thyroglobulin-specific CD4+CD25+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:7433–7439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruretagoyena M I, Sepulveda S E, Lezana J P, Hermoso M, Bronfman M, Gutierrez M A, Jacobelli S H, Kalergis A M. Inhibition of nuclear factor-κ B enhances the capacity of immature dendritic cells to induce antigen-specific tolerance in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:59–67. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AE, Sayers BL, Haniffa MA, Swan DJ, Diboll J, Wang XN, Isaacs JD, Hilkens CM. Differential regulation of naive and memory CD4+ T cells by alternatively activated dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:124–133. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt-Boyes S M, Figdor C G. Current issues in delivering DCs for immunotherapy. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:105–110. doi: 10.1080/14653240410005258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesterhuis W J, Aarntzen E H, De Vries I J, Schuurhuis D H, Figdor C G, Adema G J, Punt C J. Dendritic cell vaccines in melanoma: from promise to proof? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:118–134. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrink K, Wolfl M, Jonuleit H, Knop J, Enk A H. Induction of tolerance by IL-10-treated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:4772–4780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A E, Gad M, Kristensen N N, Haase C, Nielsen C H, Claesson M H. Tolerogenic dendritic cells pulsed with enterobacterial extract suppress development of colitis in the severe combined immunodeficiency transfer model. Immunology. 2007;121:526–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorny A, Gonzalez-Rey E, Fernandez-Martin A, Pozo D, Ganea D, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide induces regulatory dendritic cells with therapeutic effects on autoimmune disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13562–13567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504484102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rey E, Chorny A, Fernandez-Martin A, Ganea D, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide generates human tolerogenic dendritic cells that induce CD4 and CD8 regulatory T cells. Blood. 2006;107:3632–3638. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts C L, Shukair S A, Duncan K M, Harris C W, Belyavskaya E, Sternberg E M. Effects of dexamethasone on rat dendritic cell function. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:404–412. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-980195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C Q, Peng R, Beato F, Clare-Salzler M J. Dexamethasone induces IL-10-producing monocyte-derived dendritic cells with durable immaturity. Scand J Immunol. 2005;62:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstein H, Taner T, Zahorchak A F, Morelli A E, Logar A J, Gessner A, Thomson A W. Rapamycin inhibits IL-4-induced dendritic cell maturation in vitro and dendritic cell mobilization and function in vivo. Blood. 2003;101:4457–4463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnquist H R, Raimondi G, Zahorchak A F, Fischer R T, Wang Z, Thomson A W. Rapamycin-conditioned dendritic cells are poor stimulators of allogeneic CD4+ T cells, but enrich for antigen-specific Foxp3+ T regulatory cells and promote organ transplant tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;178:7018–7031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckland M, Jago C, Fazekesova H, George A, Lechler R, Lombardi G. Aspirin modified dendritic cells are potent inducers of allo-specific regulatory T-cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1895–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates P T, Krishnan R, Kireta S, Johnston J, Russ G R. Human myeloid dendritic cells transduced with an adenoviral interleukin-10 gene construct inhibit human skin graft rejection in humanized NOD-scid chimeric mice. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1224–1233. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama T, Tahara H, Thomson A W. Transduction of dendritic cell progenitors with a retroviral vector encoding viral interleukin-10 and enhanced green fluorescent protein allows purification of potentially tolerogenic antigen-presenting cells. Transplantation. 1999;68:1903–1909. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199912270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama T, Kaneko K, Morelli A E, Li W, Tahara H, Thomson A W. Retroviral delivery of transforming growth factor-β1 to myeloid dendritic cells: inhibition of T-cell priming ability and influence on allograft survival. Transplantation. 2002;74:112–119. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200207150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Wang Q, Zhang L, Pan J, Zhang M, Lu G, Yao H, Wang J, Cao X. TGF-β(1) gene modified immature dendritic cells exhibit enhanced tolerogenicity but induce allograft fibrosis in vivo. J Mol Med. 2002;80:514–523. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoukakis N, Bonham C A, Qian S, Chen Z, Peng L, Harnaha J, Li W, Thomson A W, Fung J J, Robbins P D, Lu L. Prolongation of cardiac allograft survival using dendritic cells treated with NF-κB decoy oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Mol Ther. 2000;1:430–437. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiao M M, Lu L, Tao R, Wang L, Fung J J, Qian S. Prolongation of cardiac allograft survival by systemic administration of immature recipient dendritic cells deficient in NF-κB activity. Ann Surg. 2005;241:497–505. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154267.42933.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhang X, Zheng X, Lian D, Zhang Z X, Ge W, Yang J, Vladau C, Suzuki M, Chen D, Zhong R, Garcia B, Jevnikar A M, Min W P. Immune modulation and tolerance induction by RelB-silenced dendritic cells through RNA interference. J Immunol. 2007;178:5480–5487. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang J, Gu X, Zhou Y, Gong X, Qian S, Chen Z. Administration of dendritic cells modified by RNA interference prolongs cardiac allograft survival. Microsurgery. 2007;27:320–323. doi: 10.1002/micr.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Delwig A, Altmann D M, Isaacs J D, Harding C V, Holmdahl R, McKie N, Robinson J H. The impact of glycosylation on HLA-DR1-restricted T cell recognition of type II collagen in a mouse model. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:482–491. doi: 10.1002/art.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M, Engering A, Pinet V, Pieters J, Lanzavecchia A. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:782–787. doi: 10.1038/42030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Turley S, Iyoda T, Yamaide F, Shimoyama S, Reis e Sousa C, Germain R N, Mellman I, Steinman R M. The formation of immunogenic major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide ligands in lysosomal compartments of dendritic cells is regulated by inflammatory stimuli. J Exp Med. 2000;191:927–936. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt T, Pajak B, Muraille E, Lespagnard L, Heinen E, De Baetselier P, Urbain J, Leo O, Moser M. Regulation of dendritic cell numbers and maturation by lipopolysaccharide in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1413–1424. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries I J, Krooshoop D J, Scharenborg N M, Lesterhuis W J, Diepstra J H, Van Muijen G N, Strijk S P, Ruers T J, Boerman O C, Oyen W J, Adema G J, Punt C J, Figdor C G. Effective migration of antigen-pulsed dendritic cells to lymph nodes in melanoma patients is determined by their maturation state. Cancer Res. 2003;63:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matasic R, Dietz A B, Vuk-Pavlovic S. Dexamethasone inhibits dendritic cell maturation by redirecting differentiation of a subset of cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:909–914. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing N, Maldonado M L, Bachman L A, McKean D J, Kumar R, Griffin M D. Distinctive dendritic cell modulation by vitamin D(3) and glucocorticoid pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:645–652. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piemonti L, Monti P, Allavena P, Sironi M, Soldini L, Leone B E, Socci C, Di Carlo V. Glucocorticoids affect human dendritic cell differentiation and maturation. J Immunol. 1999;162:6473–6481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltman A M, de Fijter J W, Kamerling S W, Paul L C, Daha M R, van Kooten C. The effect of calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids on the differentiation of human dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1807–1812. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200007)30:7<1807::AID-IMMU1807>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penna G, Adorini L. 1 α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J Immunol. 2000;164:2405–2411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piemonti L, Monti P, Sironi M, Fraticelli P, Leone B E, Dal Cin E, Allavena P, Di Carlo V. Vitamin D3 affects differentiation, maturation, and function of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:4443–4451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozkova D, Horvath R, Bartunkova J, Spisek R. Glucocorticoids severely impair differentiation and antigen presenting function of dendritic cells despite upregulation of Toll-like receptors. Clin Immunol. 2006;120:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.04.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A E, Gad M, Walter M R, Claesson M H. Induction of regulatory dendritic cells by dexamethasone and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) Immunol Lett. 2004;91:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann M F, Kopf M, Marsland B J. Chemokines: more than just road signs. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:159–164. doi: 10.1038/nri1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Schaniel C, Lenig D, Mackay C R, Qin S, Lanzavecchia A. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2760–2769. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2760::AID-IMMU2760>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrod K R, Chang C K, Liu F C, Brennan T V, Foster R D, Kang S M. Targeted lymphoid homing of dendritic cells is required for prolongation of allograft survival. J Immunol. 2006;177:863–868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R, Davalos-Misslitz A C, Rot A. CCR7 and its ligands: balancing immunity and tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:362–371. doi: 10.1038/nri2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Liu Y, Wang J, Ding G, Zhang W, Chen G, Zhang M, Zheng S, Cao X. Induction of allospecific tolerance by immature dendritic cells genetically modified to express soluble TNF receptor. J Immunol. 2006;177:2175–2185. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzardelli C, Pavelka N, Luchini A, Zanoni I, Bendickson L, Pelizzola M, Beretta O, Foti M, Granucci F, Nilsen-Hamilton M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Effects of dexamethazone on LPS-induced activationand migration of mouse dendritic cells revealed by a genome-wide transcriptional analysis. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1504–1515. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Delwig A, Hilkens C M, Altmann D M, Holmdahl R, Isaacs J D, Harding C V, Robertson H, McKie N, Robinson J H. Inhibition of macropinocytosis blocks antigen presentation of type II collagen in vitro and in vivo in HLA-DR1 transgenic mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R93. doi: 10.1186/ar1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmer P M, van der Vlag J, Adema G J, Hilbrands L B. Dendritic cells activated by lipopolysaccharide after dexamethasone treatment induce donor-specific allograft hyporesponsiveness. Transplantation. 2006;81:1451–1459. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000208801.51222.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racke M K, Bonomo A, Scott D E, Cannella B, Levine A, Raine C S, Shevach E M, Rocken M. Cytokine-induced immune deviation as a therapy for inflammatory autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1961–1966. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala F, Abad S, Ezine S, Taupin V, Masson A, Bach J F. G-CSF therapy of ongoing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis via chemokine- and cytokine-based immune deviation. J Immunol. 2002;168:2011–2019. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X C, Zand M S, Li Y, Zheng X X, Strom T B. On histocompatibility barriers, Th1 to Th2 immune deviation, and the nature of the allograft responses. J Immunol. 1998;161:2241–2247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]