Abstract

Despite the well established sympathoexcitation evoked by chemoreflex activation, the specific sub-regions of the central nervous system underlying such sympathetic responses remain to be fully characterized. In the present study we examined the effects of intermittent chemoreflex activation in awake rats on Fos-immunoreactivity (Fos-ir) in various subnuclei of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), as well as in identified neurosecretory preautonomic PVN neurons. In response to intermittent chemoreflex activation, a significant increase in the number of Fos-ir cells was found in autonomic-related PVN subnuclei, including the posterior parvocellular, ventromedial parvocellular and dorsal-cap, but not in the neurosecretory magnocellular-containing lateral magnocellular subnucleus. No changes in Fos-ir following chemoreflex activation were observed in the anterior PVN subnucleus. Experiments combining Fos immunohistochemistry and neuronal tract tracing techniques showed a significant increase in Fos-ir in rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM)-projecting (PVN-RVLM), but not in nucleus of solitarii tract (NTS)-projecting PVN neurons. In summary, our results support the involvement of the PVN in the central neuronal circuitry activated in response to chemoreflex activation, and indicate that PVN-RVLM neurons constitute a neuronal substrate contributing to the sympathoexcitatory component of the chemoreflex.

Keywords: chemoreflex, arterial chemoreceptors, Fos protein, paraventricular nucleus, sympathetic activity

1 - INTRODUCTION

The arterial chemosensitive cells located in the carotid body, at the bifurcation of the carotid arteries, are very sensitive to a reduction in arterial PO2 (Biscoe and Dunchen, 1990). Potassium cyanide (KCN), used experimentally for activation of chemosensitive cells, causes cytotoxic-hypoxia and produces cardiovascular and respiratory responses similar to those evoked by hypoxic-hypoxia in awake rats (Franchini and Krieger, 1993; Bao et al., 1997; Barros et al., 2002). The activation of the chemoreflex in awake rats produces sympathoexcitation (increase in arterial pressure) and parasympathoexcitation (bradycardia) through activation of independent mechanisms (Haibara et al., 1995).

While it is well established that chemoreceptor primary afferent fibers terminate in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) (Spyer, 1990), the projections from this nuclei to other areas in the brain involved with the sympathoexcitatory component of this reflex are not fully characterized. In this sense, functional evidence indicates that projections from the NTS to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), a key center for autonomic and neuroendocrine integration (Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980), as well as the parabrachial nuclei contribute to the sympathoexcitatory response to chemoreflex activation in awake rats (Berquin et al., 2000a, b; Olivan et al., 2001; Haibara et al., 2002). Moreover, recent data from our laboratory further support an important role for the PVN in the integration of autonomic responses to chemoreflex activation (Olivan et al., 2001; Cruz et al., 2004).

Anatomical and electrophysiological studies demonstrated the presence of direct connections between the NTS and the PVN (Ricardo and Koh, 1978; Kooy et al., 1984; Kannan and Yamashita, 1985; Krukoff et al., 1995; Hardy, 2001), as well as direct connections from the PVN to the rostral ventrolateral medulla [RVLM (Ricardo and Koh, 1978; Spyer, 1990; Koshiya and Guyenet, 1996; Badoer and Meerolli, 1998; Badoer, 2001; Coote et al., 1998; Cunningham et al., 1990; Hardy et al., 2001; Stern and Zhang, 2003)] and the spinal cord (Shafton et al., 1998; Badoer, 2001; Stocker et al., 2004). Recent studies documented that a bilateral electrolytic lesion of the PVN produced a significant reduction in the magnitude and duration of the pressor response evoked by chemoreflex activation with KCN (Olivan et al., 2001). Moreover, an involvement of PVN neurons in the increased renal sympathetic nerve activity produced by chemoreflex activation with KCN was recently demonstrated (Reddy et al., 2005). While these data support the concept that the PVN plays an important role in the central neuronal circuitry underlying the processing of the sympathoexcitatory component of the chemoreflex, the precise PVN neuronal populations activated during the chemoreflex remain to be established.

In the present study, we used Fos immunohistochemistry along with neuronal tract tracing approaches to map neuronal populations activated within specific sub-regions of the PVN in response to intermittent chemoreflex activation by intravenous administration of KCN. Our results support a non-homogeneous activation of PVN subnuclei in response to chemoreflex activation, affecting predominantly preautonomic ones, including PVN neurons innervating the RVLM.

2 – EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

2.1 - Animals

Wistar male rats weighting 270–310 g were used in all experimental protocols. All the experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Ethical Principles for Animal Experimentation established by the Brazilian Committee for Animal Experimentation and approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (Protocol # 057/2003).

2.2 – Arterial pressure and heart rate recordings

One day before the experiments, while rats were under tribromoethanol [2.5%-100ml/kg (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, (USA)] anesthesia (i.p.), a catheter [PE-10 connected to PE-50 (Clay Adams, Parsippany, NJ)] was inserted into the femoral artery for measurement of pulsatile arterial pressure (PAP) and a second catheter was inserted into the femoral vein for systemic administration of drugs. PAP was measured with a pressure transducer (model CDX III, Cobe Laboratories, Lakewood, CO) connected to a polygraph (Narcotrace 80, Narco Bio-Systems, Austin, TX). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was derived from the PAP using a universal coupler (model 7179, Narco Bio-Systems), and heart rate (HR) was quantified from the PAP using a Biotachometer Coupler (model 7302, Narco Bio-Systems) and recorded in the same polygraph.

2.3 - Activation of the chemoreflex with potassium cyanide (KCN)

Twenty four hours after catheters implantation, the cardiovascular parameters were recorded simultaneously in pairs of animals: one rat received intermittent injections of KCN (80 µg/0.05 ml/injection, performed every 3 min during a total period of 30 min) for stimulation of the chemoreflex and the second rat received intermittent injection of saline (0.9 %) as a volume control. Before the experimental protocols, rats from both groups received an intravenous injection of KCN to verify if the venous catheter was patent. When compared to control rats, no differences in PVN Fos-ir were observed following the single injection of KCN used to test the venous catheter (results not shown). The values of mean arterial pressure and heart rate are representative of the peak values obtained in response to chemoreflex activation. The magnitude of peak changes in mean arterial pressure (56±5 vs 46±5 mmHg, F=0.35, P<0.8) and heart rate (−266±21 vs −270±12 bpm, F=1.0, P<0.4) in response to the initial and final KCN injections, respectively, were not statistically different.

2.4 Baroreflex activation

In a separate group of rats (n= 6) the baroreflex was intermittently activated in awake rats using phenyleprine [1.0 or 1.5 µl/0.05 ml, iv., activated every 3 min during 30 min], while control rats received an intravenous injection of the same volume of saline (0.9%). The magnitude of the pressor response to phenylephrine injection was similar to that produced by chemoreflex activation with KCN. Thirty min after the last activation, the animals were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with fixative as described elsewhere.

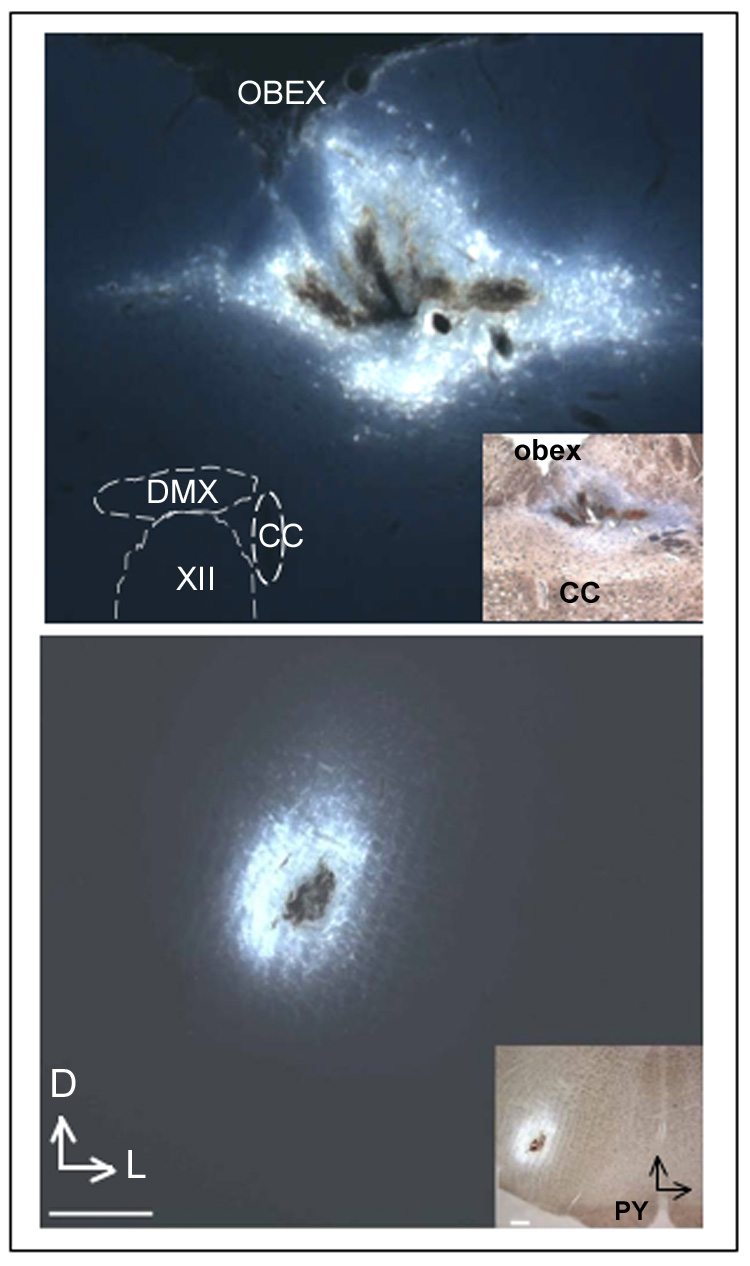

2.5 - Retrograde labeling of NTS- and RVLM-projecting PVN neurons

Unilateral microinjections of Fluorogold (2%, 100 nl, Fluorochrome Inc., Denver, CO, USA) were performed in the NTS or in the RVLM (n= 4 for each case) in rats under tribromoethanol anesthesia 4–6 days before intermittent chemoreflex activation. The stereotaxic coordinates used for microinjections into the caudal aspect of the commissural subnucleus of the NTS or in the RVLM were in accordance with the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986). Figure 1 shows representative examples of the injection site following a unilateral microinjection of Fluorogold in the caudal aspect of the commissural NTS or the RVLM. In all cases, RVLM injection sites were contained within the caudal pole of the facial nucleus to ~ 1 mm more caudal, and were ventrally located with respect to the nucleus ambiguous (Stern and Zhang, 2003).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs showing representative examples of injection sites following unilateral microinjection of Fluorogold into the caudal aspect of the commissural NTS (upper panel) and the RVLM (lower panel). Insets: NTS and RVLM injection sites shown at a lower magnification. Scales=200 µm. DMX=dorsal motor nucleus of vagus; CC=central canal; XII=hypoglossal nucleus, PY=pyramidal tract; Vertical and horizontal arrows point to dorsal (D) and lateral (L) aspects of the brainstem.

2.6 - Tissue Preparation and Fos Immunocitochemistry

In most studies, unless indicated otherwise, Fos immunohistochemistry was assessed thirty minutes following the last chemoreflex activation (i.e., 60 min following the first stimulation). Rats were deeply anesthetized with thionembutal® [0.1ml/100g, i.p (Abbot Laboratories, North Chicago, USA)] and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 50ml) followed by 4% PFA (500 ml). The brains were post fixed in 4% PFA overnight, and then cryoprotected with 0.1M PBS containing 30% sucrose, overnight. Brain sections (30 µm) were cut using a cryostat (Micron, International GmbH, Waldorf, Germany), and sequentially divided in three groups: experimental group; control group (omission of the primary antibody), and Nissl staining group (cresyl-violet) in order to better delineate the specific sub-nuclei used for quantification and identify the antero-posterior aspects of the PVN.

In a first set of experiments, brain sections were incubated in normal goat serum [(1:250), Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove MO, USA] during 2h. Sections were then incubated overnight in the presence of a rabbit anti-Fos antibody [(1:4000), sc-52, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA], followed by 2h incubation in the presence of a goat anti-rabbit biotinylated antibody [(1:500), Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove MO, USA]. Sections were then processed with the avidin-biotin complex (ABC-Standart, 1:50, 2 h; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and the immunoreactivity was visualized by subsequent addition (5 min) of H202 0.007% and diaminobenzidine [DAB, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA (50 mg/100 ml)].

In a second set of experiments, we co-localized Fos immunoreactivity in retrogradely-labeled NTS- and RVLM-projecting PVN neurons (n=4 rats/group). To this end, dual-immunofluorescent reactions using antibodies against Fos and the tracer Fluorogold were performed. Sections were incubated overnight in the presence of an antibody cocktail containing a goat anti-Fos [(1:2000) Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA], and a rabbit anti Fluorogold [1:10.000; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA]. Reactions in primary antibodies were followed by 4h incubation in a cocktail of fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies containing a donkey anti-goat Cy3-labeled and a donkey anti-rabbit Cy2-labeled antibodies (1:400, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove MO, USA). Finally, in a third set of experiments we colocalized Fos immunoreactivity in immunoidentified oxytocin (OT) and vasopressin (VP) magnocellular neurons. General procedures were the same as above. Sections were incubated overnight in the presence of an antibody cocktail containing a goat anti-Fos [(1:2000) Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA], guinea pig anti-oxytocin [(1:50000) Peninsula, San Carlos, CA, USA] and rabbit anti-vasopressin [(1:20000) Peninsula, San Carlos, CA, USA]. Reactions in primary antibodies were followed by 4h incubation in a cocktail of fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies containing donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488-labeled (1:250, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA); donkey anti-guinea pig Cy5-labeled and a donkey anti-rabbit Cy3-labeled antibodies (1:50 and 1:400 respectively, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, MO, USA).

2.7 - Quantification of single-labeled, Fos-ir neurons in the PVN

Fos immunoreactivity was visualized using a microscope [Axioskop (Carl Zeiss, Germany)] connected to a digital camera (Axiocam HRc, Carl Zeiss, Vision GmbH, Germany). Images were captured using a computerized AxioVision 3.0 system (Carl Zeiss, Vision GmbH, Germany). Fos-ir neurons were identified by the presence of dark, nuclear staining, and were manually counted. Fos-ir neurons were systematically quantified within specific rostro-caudal coordinates of the anterior, medial and posterior sub-regions of the PVN (Chan et al., 1998), at a 90 µm interval. In the anterior PVN, containing the anterior PVN subnucleus (PaA), Fos-ir was counted in three rostro-caudal levels (from −1.5 to −1.7 mm caudal to bregma). In the medial PVN, containing the lateral magnocellular (LM), dorsal-cap (DC) and ventral-medial parvocellular (PaV) subnuclei, Fos-ir neurons were counted in four rostro-caudal levels (from −1.8 to −2.1 mm caudal to bregma)]. In the posterior aspects of the PVN containing the posterior parvocellular subnucleus (PaPo), Fos-ir neurons were counted in three rostro-caudal levels (from −2.1 to −2.3 mm caudal to bregma). The atlas of the Paxinos and Watson (1996) was used as a reference. On average, 7–12 sections (30 µm) were counted from each rostro-caudal coordinate of the anterior, medial and posterior PVN. We attempted to equalize the total number of sections sampled in each animal. However, in some cases sections were lost during the sectioning and/or incubation procedure. Thus, the mean number of positive Fos-ir per section per subnucleus region was calculated within each experimental group for quantitative purposes.

2.8 - Mapping of double-labeled cells

Stained sections were examined with a Leica TCS SL confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany). Confocal stacks of 6 consecutive optical planes (1 µm thick) were obtained using appropriate emission and excitation wavelengths. The argon-krypton laser was used to excite the Cy2 and Cy3 fluorochromes at 488 and 543 nm, respectively. To determine co-localization of the two fluorescent markers within single cells, confocal images obtained from the different fluorophores were merged. Quantification of the number of double-labeled neurons was done as previously described (Stern and Zhang, 2003). Briefly, retrogradely labeled and/or Fos immunoreactive neurons were counted in the ipsilateral (with respect to the brainstem injection), PaV and PaPo subnuclei, previously shown to contain brainstem-projecting PVN neurons (Ricardo and Koh, 1978; Cunningham et al., 1990; Spyer, 1990; Koshiya and Guyenet, 1996; Badoer and Merolli, 1998; Coote et al., 1998; Badoer, 2001; Hardy, 2001; Stern and Zhang, 2003; Coote, 2004). The number of neurons labeled with Fluorogold alone, Fos alone, and the number of double-labeled neurons were counted using imaging analysis software (Image Pro, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). These data were obtained from 6 sections of the PVN within the specified coordinates, which contained the ventral parvocellular (PaV) and the dorsal cap (DC) preautonomic subnuclei. Within each one of the experimental groups (e.g., saline- and KCN-treated rats), neurons sampled were pooled together, and the percentage of colocalization determined. In addition, the percentage of double-labeled cells was calculated for each experimental animal, and a mean value was then obtained for each experimental group. A similar approach was used to detect colocalization of Fos in immunoidentified OT and VP magnocellular neurosecretory neurons in the lateral magnocellular (LM) and medial magnocellular (MM) PVN subnuclei.

2.9 - Control groups for Fos immunoreactivity

To determine whether the anesthesia itself contributed to Fos-ir, one group of rats (n=3) was submitted only to the anesthesia procedure, and the number of Fos-ir neurons were determined as described above. Another control group consisted of rats (n=3) submitted both to the anesthetic and catheterization procedure, and one day after, brains were extracted and the number of Fos-ir neurons were determined. We verified that the number of Fos-ir neurons in the different subnuclei of the PVN in these two control groups was similar to the control group that received one injection of KCN to test the venous catheter and the intermittent saline injections (results not shown)]. Data obtained from these two control groups were not combined with data from the saline group for further comparisons against the KCN-treated group.

2.10 - Statistics analysis

To compare changes in Fos-ir according to experimental group (i.e., saline- vs. KCN-treated) and topographical distribution within the PVN, the mean number of positive Fos-ir per section per subnucleus region was calculated within each experimental group. Data were analysed using one or two-way ANOVA, as indicated in the text, followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. Two complementary analyses were used to compare differences in the incidence of double-labeled neurons (i.e., retrogradely-labeled and Fos-ir) between experimental groups. Firstly, neurons sampled from rats in each experimental groups (e.g., saline- and KCN-treated rats), were pooled together and the percentage of colocalization was determined within each group. A Chi Square test was used to statistically compare differences in double-labeling incidence between groups. In addition, the percentage of double-labeled cells was calculated for each experimental animal, and a mean value was then obtained for each experimental group. A Student’s t test was used to compare difference between experimental groups. All values are reported as means ± SEM.

3 - RESULTS

Cardiovascular responses to chemoreflex activation in awake rats

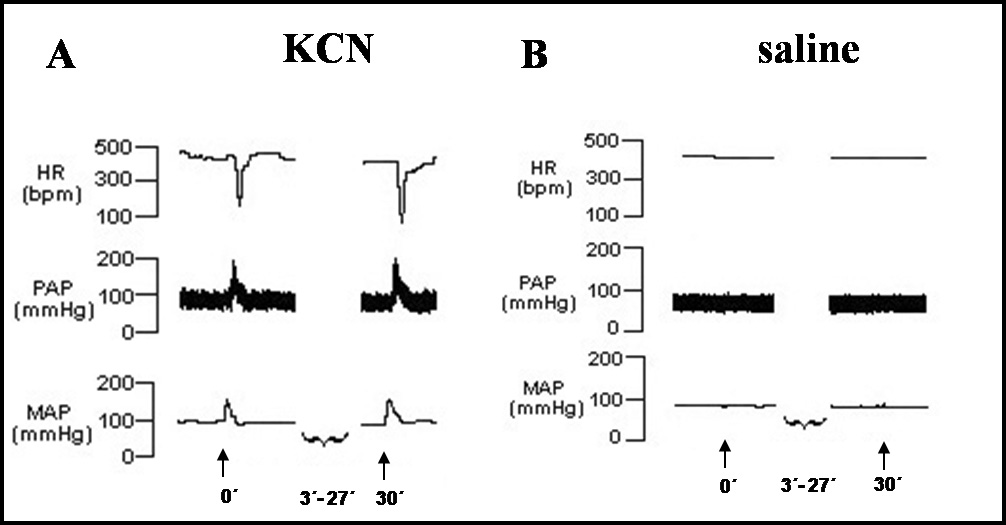

Intermittent chemoreflex activation in awake rats elicited hypertension and bradycardic response (ΔMAP = +52 ± 5 mmHg; ΔHR = −265 ± 9 bpm; n=7), while injection of saline produced negligible effect on both parameters (ΔMAP = +2 ± 1 mmHg; ΔHR = −4 ± 4 bpm; n=7, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A- Tracings showing changes in heart rate (HR), pulsatile arterial pressure (PAP) and mean arterial pressor (MAP) in response to the first (at the time 0) and the last (at 30 min) injection of potassium cyanide [KCN, iv (arrow)] in an awake rat representative of the group. B- Tracings of one awake rat showing no changes in MAP and HR in response to vehicle (saline) injection [iv (arrow)]. The injections were performed every 3 min during 30 min.

Changes in Fos-ir within discrete PVN subnuclei of rats submitted to chemoreflex activation

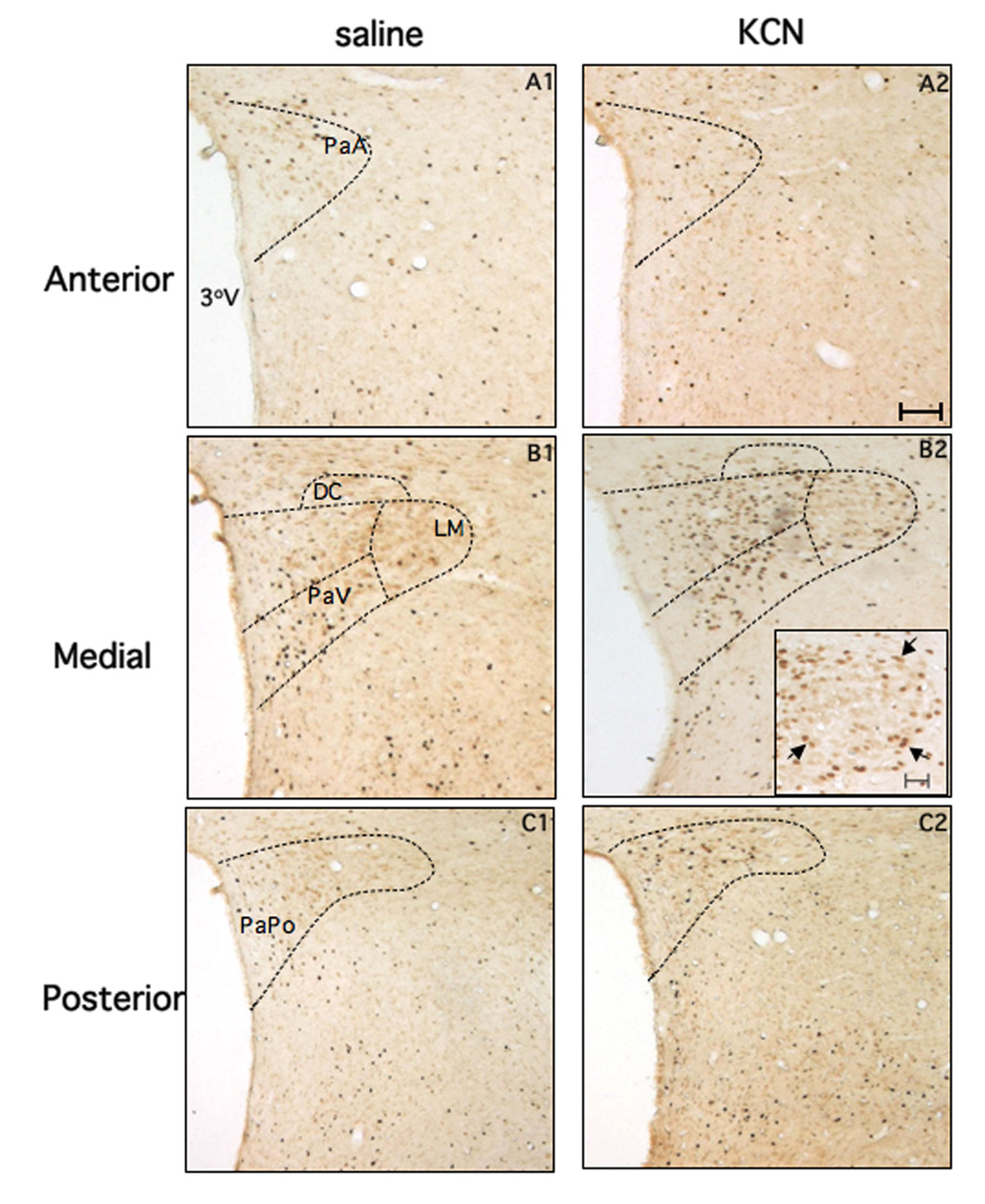

Representative examples of Fos-ir in the anterior, medial, and caudal PVN levels (see Methods) of rats submitted to injection of saline (left panels) or KCN (right panels), are shown in Figure 3. In general, the forebrain of rats submitted to saline injection presented few Fos-ir neurons in all rostro-caudal levels of the PVN. On the other hand, an increased number Fos-ir neurons in the medial and posterior aspects of the PVN was apparent following chemoreflex activation with KCN. Results from a detailed quantitative analysis according to specific PVN subnuclei are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs showing Fos-ir neurons at three rostro-caudal sections (30 µm thickness) representative of the anterior, medial and posterior PVN (objective magnification, 5×). Panels A1, B1 and C1 are from rats submitted to intermittent injection of saline (iv) whereas panels A2, B2 and C2 are from rats submitted to intermittent chemoreflex activation with KCN (iv). The insert in the panel B2 illustrates the LM region at higher magnification (objective magnification, 20×, bar 20µm), to better depict the presence of Fos-ir neurons (arrows) located predominantly in the periphery, but not in the core of the subnucleus. 3°V= third ventricle. Bar (panel A1): 100 µm. The area correspondent to the PVN subnuclei was outlined in accordance with the atlas of Paxinos and Watson.

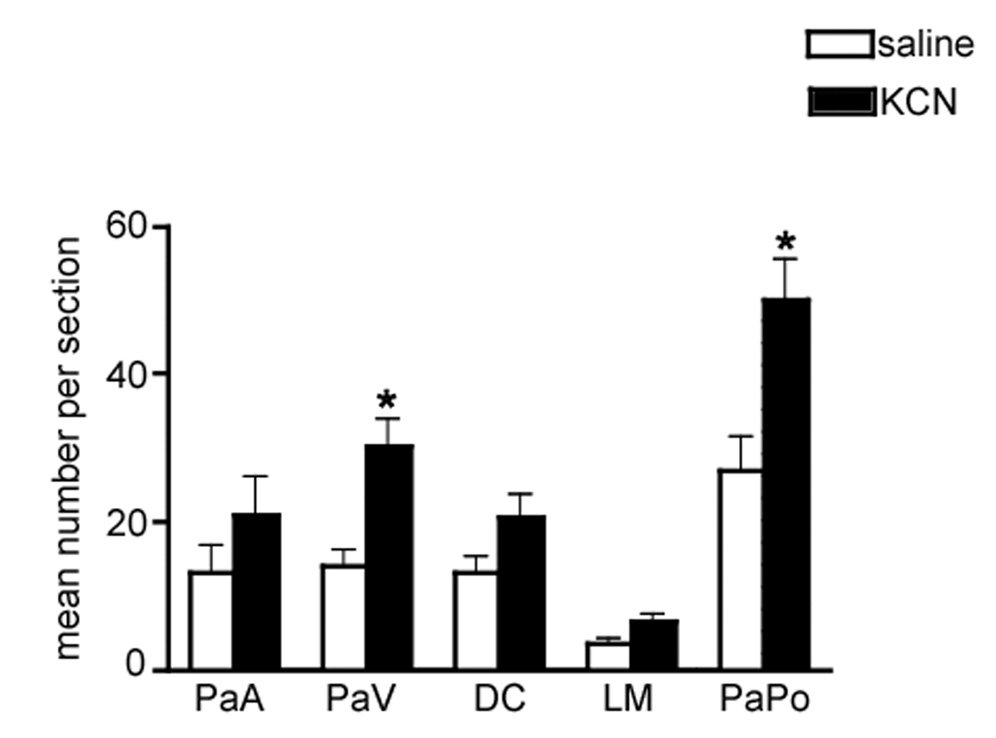

Figure 4.

Mean number of Fos-ir neurons per section in different PVN subnuclei following intermittent chemoreflex activation. PaA: anterior parvocellular, PaV: ventromedial parvocellular; DC: dorsal cap; LM: lateral magnocellular; PaPo: posterior parvocellular. *P<0.001, when compared to saline group. Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test.

Results from a 2 way ANOVA indicated that Fos-ir in the PVN varied significantly as a function of the treatment (saline vs. KCN, F= 12.7, df=1; P< 0.0001) as well as subnuclei distribution (F= 45.0, df= 4, P< 0.0001). Significant interactions between the two factors were also observed (F= 4.5, df= 4, P< 0.05). Bonferroni Post hoc tests indicated a significant increase in the number of Fos-ir neurons following chemoreflex activation in the ventromedial (VM) and in the posterior (PaPo) subnuclei (P< 0.01 and P< 0.001, respectively). On the other hand, no changes were observed in the anterior (PaA), dorsal cap (DC) or lateral magnocellular (LM) subnuclei (P<0.05 in all cases). Similar increase in PVN Fos-ir was observed in a subset of animals (n=3) in which Fos immunohistochemistry was assessed 60 minutes following the last chemoreflex activation [i.e., 90 min following the first stimulation (not shown)].

Fos-ir in retrogradely-labeled PVN-RVLM and PVN-NTS neuronal populations

The topographical distribution of Fos-ir following chemoreflex supports activation of PVN neurons predominantly located in PVN subnuclei enriched with preautonomic neurons (e.g., PaV and PaPo). To further confirm this, we combined Fos immunohistochemistry with tract tracing techniques to label preautonomic PVN neurons projecting to two separate targets, the RVLM or the NTS (see Methods; Figure 1). The degree of colocalization of Fluorogold-labeled PVN neurons and Fos immunoreactivity in saline and KCN treated rats was then determined (see Methods).

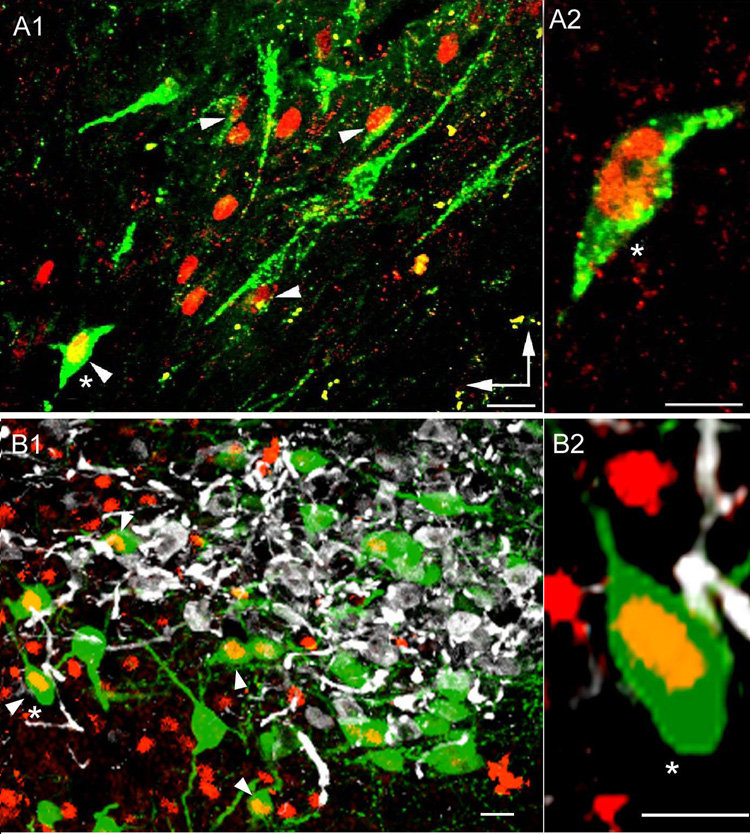

A total number of 340 and 231 PVN-RVLM neurons and 112 and 197 For-ir neurons, located in the medial and caudal PVN, were counted in sections obtained from saline and KCN treated rats, respectively. A representative example of a high power confocal photomicrograph displaying simultaneous Fos and Fluorogold-stained PVN-RVLM is shown in Figure 5A. Our results indicate a significant increase in the number of PVN-RVLM neurons expressing Fos-ir following chemoreflex activation. When data obtained within each experimental group was pooled together, we found the overall proportion of PVN-RVLM neurons displaying Fos-ir to increase from 6.9% (25/340) in saline-treated rats, to 27.3% (63/231) in KCN-treated rats (P< 0.0001, Chi-square test). No differences in the incidence KCN-induced Fos-ir were observed among PVN-RVLM neurons located in the PaV (23/65, 35.3%), DC (20/62, 35.2%) or the PaPo (20/104, 19.2%) subnuclei (P> 0.5, Chi-square test). Conversely, the overall proportion of Fos-ir neurons retrogradely-labeled from the RVLM increased from 22% (25/112) in saline-treated rats, to 32% (63/197) (P< 0.03, Chi-square test) in KCN-treated rats. S

Figure 5.

Fos-ir in identified preautonomic and neurosecretory PVN neurons following intermittent chemoreflex activation with KCN. A- Fos-ir in retrogradely-labeled PVN-RVLM neurons. In A1, a representative confocal photomicrograph showing PVN-RVLM projecting neurons (green) and Fos-ir (red) in the ventro-medial PVN subnucleus is shown. Arrowheads point to examples of double-labeled neurons. A2- Representative example of a retrogradely-labeled PVN-RVLM projecting neuron (same neuron as in A1, marked with an asterisk) displaying clear nuclear Fos-ir. B- Fos-ir in OT and VP immunoreactive neurosecretory neurons. In B1, a representative confocal photomicrograph showing OT (green), VP (white) and Fos-ir (red) in the lateral magnocellular subnucleus is shown. Arrowheads point to examples of double-labeled neurons. B2- Representative example of an OT neuron (same neuron as in B1, marked with an asterisk) displaying clear nuclear Fos-ir. Scale bars= 20 µm. Vertical and horizontal arrows in A point to dorsal and medial aspects of the PVN.

Similar results were obtained when percentages of double-labeled cells were calculated within each animal, and mean values obtained for each experimental group (PVN-RVLM neurons displaying Fos-ir: 7.45 ± 1.0% in saline-treated rats; 28.3 ± 2.7% in KCN-treated rats; n=4; P< 0.001, Student’s t test; Fos-ir neurons retrogradely-labeled from the RVLM: 22.9 ± 3.6% in saline-treated rats; 32.6 ± 1.9% in KCN-treated rats; n=4; P< 0.05, Student’s t test).

On the other hand, we failed to detect any colocalization between Fos-ir and PVN-NTS projecting neurons (results not shown). For these studies, a total of number of 201 PVN-NTS and 86 Fos-ir neurons were sampled in saline-treated rats, whereas a total number and 197 PVN-NTS neurons and 75 Fos-ir were sampled in KCN-treated rats.

Fos-ir in identified OT and VP magnocellular neurons

Interestingly, a consistent finding within the LM subnucleus was that KCN-induced Fos-ir neurons were preferentially located within its peripheral ring (an area known to contain mostly OT neurons (See Fig. 3B, Inset), with few Fos-ir neurons located within the core of the LM (known to mostly contain VP neurons) (Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980). To confirm whether chemoreflex stimulation selectively activated magnocellular neurosecretory OT neurons, we performed triple immunofluorescent reactions to directly assess Fos-ir in identified OT and VP neurons. Representative examples are shown in Fig. 5B. A total number of 292 OT and 103 VP neurons were counted in sections obtained from saline-treated rats, while 338 and 254 OT and VP neurons were counted in KCN treated rats. Our results indicate a significant increase in the number of OT neurons expressing Fos-ir following chemoreflex activation. The proportion of OT neurons displaying Fos-ir increased from 14.4% (42/292) in saline-treated rats, to 26.0% (88/338) in KCN-treated rats (P< 0.001, Chi-square test). Conversely, KCN treatment did not change the proportion of VP neurons displaying Fos-ir (saline: 2.9% (3/103); KCN: 1.2% (3/254) (P> 0.1). Interestingly, a significantly larger proportion of OT neurons were found to express Fos-ir, when compared to VP neurons under control conditions (Fig. 5B).

Cardiovascular responses and Fos-ir in the PVN following baroreflex activation in awake rats

It could be argued that changes in the number of Fos-ir neurons observed in the PVN in response to the intermittent activation of the chemoreflex could be, at least in part, secondary to the baroreflex activation, following the relatively large increase in arterial pressure produced by chemoreflex activation. Therefore, as a control, we tested the effects of intermittent activation of the baroreflex with phenylephrine (iv) on Fos-ir in the PVN. Baroreflex activation by phenylephrine injection produced an increase in MAP of similar magnitude to that evoked by KCN (ΔMAP = +51 ± 1 vs +1 ± 1 mmHg in saline). The bradicardic response however, was of greater magnitude (ΔHR = −66 ± 19 vs +3 ± 4 bpm in saline, n=6). As summarized in Table I baroreflex activation with phenylephrine produced no significant changes in the number of Fos positive cells when compared with the saline treated groups (2 way ANOVA, F= 0.2, P>0.6).

Table I.

Changes in For-ir levels within various PVN subnuclei following intermittent baroreflex activation with phenylephrine.

| subnuclei of PVN | Fos-ir saline | Fos-ir Phenyl |

|---|---|---|

| PaA | 55±7 (4) | 52±15 (6) |

| PaV | 92±17 (4) | 62±10 (6) |

| DC | 61±5 (5) | 47±9 (6) |

| LM | 21±2 (5) | 17±2 (6) |

| PaPo | 91±10 (4) | 155±22 (7) |

The animals received injections of phenylephrine [baroreflex activation (1.5 µg/0.05 ml, iv)] or injections of saline (154 mM, iv) every 3 min during 30 min. PVN: paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; PaA: anterior PVN; LM: lateral magnocellular PVN; DC: dorsal cap PVN; PaV: ventro-medial PVN; PaPo: posterior PVN. Number of animals indicated between parentheses. Values represent mean ± SEM.

4 – DISCUSSION

Despite the fact that it is well established that chemoreflex activation produces sympathoexcitation and a concomitant increase in MAP, the specific neuronal substrates within the central nervous system underlying such sympathetic responses remain to be fully characterized. Using Fos immunoreactivity as a marker of neuronal activation, we demonstrate in this study that intermittent chemoreflex stimulation in awake rats activates neurons in several PVN sub-nuclei, most remarkably those containing preautonomic neurons. In fact, our studies indicate activation of sympathetic-related PVN-RVLM neurons in response to chemoreflex activation, supporting their involvement in the central neuronal pathway underlying cardiovascular responses to this stimulus. This is to our knowledge, the first study to evaluate in details changes in Fos expression in identified neuronal populations within the PVN following acute intermittent chemoreflex activation in awake rats.

Involvement of the PVN in the neural pathway mediating the chemoreflex

The PVN is a complex cytoarchitectural hypothalamic region subdivided in different subnuclei, comprising distinct neurochemical and functional neuronal populations. These include, 1) OT and VP magnocellular neurosecretory neurons, which project to the posterior pituitary, and are concentrated in the lateral magnocellular (LM) subnucleus; 2) median eminence-projecting neurosecretory neurons (immunoreactive to CRH, TSH, ANGII, among others), concentrated in the anterior parvocellular subnucleus, and 3) preautonomic neurons that send long descending projections to other autonomic centers, including the NTS, RVLM and intermediate lateral column of the spinal cord (Ricardo and Koh, 1978; Kooy et al., 1984; Cunningham et al., 1990; Krukoff et al., 1995; Coote et al., 1998; Shafton et al., 1998; Badoer and Merolli, 1998; Yang and Coote, 1998; Tagawa and Dampney, 1999; Badoer, 2001; Hardy, 2001; Coote, 2004; Stocker et al., 2004). The latter are concentrated in the parvocellular ventromedial, dorsal cap and parvocellular posterior subnuclei.

Our results show that intermittent chemoreflex activation induced a significant increase in the number of Fos-ir neurons in the ventromedial and posterior subnuclei, and to a lesser extent in the lateral magnocellular PVN subnucleus, further supporting the PVN involvement in the neural pathway of the chemoreflex. This is in general agreement with previous studies in which chemoreceptors were stimulated by hypoxia. For example, Smith et al. (1995), using graded hypoxic stimuli, determined that Fos expression in the PVN was dependent on the O2 content, with PVN neurons being recruited at O2 levels lower than 12%. This result likely explains reported differences in the degree of Fos-ir following chemoreflex activation between the present study, and a recent work by Berquim et al. (2000a, b). While a moderate increase in PVN Fos expression was found in the latter (using a “threshold” hypoxic stimulus of 11% of O2), a more robust increament was described in the study using KCN administration, which as stated above, mimicked the pattern and magnitude of cardiovascular responses elicited by 5–7% O2 hypoxic hypoxia.

The involvement of the PVN in the chemoreflex is further supported by recent work demonstrating activation of PVN neurons following tissue hypoxia induced by exposure to CO (Bodineau and Larnicol, 2001) and by hypobaric hypoxia following altitude exposure (Luo et al., 2000). However, none of those studies performed a detailed analysis of the topographical distribution of Fos-ir within various PVN subnuclei, or localized Fos-ir in discretely identified subpopulations of PVN neurons.

Distribution of Fos-ir in identified PVN neuronal populations in response to chemoreflex activation

The involvement of preautonomic PVN subnuclei in the sympathoexcitatory component of the chemoreflex is further supported by our combined Fos-ir and neuroanatomical tracing studies. These studies showed a significant increase in Fos-ir in PVN-RVLM projecting neurons. Accumulating evidence supports an important role for this pathway in the control of basal sympathetic nerve activity (Allen, 2002; Coote et al., 1998; Tagawa and Dampney, 1999; Teppema et al., 1997), as well as elevated activity during pathological conditions, such as hypertension (Akine et al, 2003; Allen, 2002) and water deprivation (Stocker et al., 2004). Furthermore, the RVLM, a key brainstem area for the control of both tonic and reflex of the sympathetic outflow, is also involved in the mediation of the sympathoexcitatory response of the chemoreflex (Smith et al., 1995; Koshiya and Guyenet, 1996; Hirooka et al., 1997). The involvement of PVN-RVLM neurons in the sympathoexcitatory component of the chemoreflex is also in agreement with previous functional experiments from our laboratory (Olivan et al, 2001), showing that a bilateral lesion of the PVN resulted in a significant reduction in the pressor, but not in the bradycardic response to chemoreflex activation. Moreover, our findings are in line with those by Reddy et al. (2005) showing that PVN neurons play a key modulatory role in sympathetic responses to peripheral chemoreceptors activation in anesthetized rats.

A significant proportion of PVN-RVLM neurons did not display Fos-ir following chemoreflex activation, suggesting that a small population of PVN-RVLM neurons are activated following this challenge. Interestingly, a similar partial activation of PVN-RVLM neurons was recently reported in water-deprived rats (Stocker et al., 2004), and in response to haemorrhage (Badoer and Merolli, 1998). It will be important to determine in future studies whether the subsets of PVN-RVLM neurons activated by these various stimuli belong to a similar pool of PVN neurons (i.e., activated by all these stimuli), or alternatively, whether they represent distinct, stimuli-specific subsets of PVN-RVLM neurons. It is also worth mentioning that the total number of Fos-ir PVN neurons following chemoreflex activation exceeded the number of Fos-ir PVN-RVLM neurons. Thus, our results suggest that PVN neurons projecting to other regions in the CNS may be activated by the chemoreflex. These include spinally-projecting PVN neurons, previously shown to play also an important role in the regulation of sympathetic outflow to the cardiovascular system (Badoer and Merolli, 1998; Coote et al., 1998; Yang and Coote, 1998; Badoer, 2001). Further studies will be needed to address this possibility.

Differently from PVN-RVLM neurons, our studies indicate that PVN-NTS projecting neurons, suggested to be involved in the modulation of the baroreflex (Coote, 2004), did not show Fos-ir following chemoreflex activation. However, as stated above, the lack of Fos expression in this PVN neuronal population sending projections to NTS does not rule out the involvement of this pathway in the modulation of chemoreflex-evoked responses.

While our results indicate no significant increase in Fos-ir within the LM subnucleus, a region containing both OT and VP neurosecretory neurons (Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980), a more detailed analysis in immunohistochemically identified neurosecretory neurons within this region demonstrated a significant increase in Fos-ir in OT but not VP neurons. The functional significance of OT neurosecretory neuronal activation in relation to cardiovascular responses associated with the chemoreflex remains at present unknown. It is worth mentioning that previous reports documented increased levels of both OT and VP neuropeptides following chemoreflex activation (Share and Levy, 1966; Chen and Du, 1999; Montero et al., 2006).

Activation of the arterial baroreceptors secondary to the increase in the arterial pressure elicited by chemoreflex activation could also contribute to Fos expression in the PVN. To determine whether this was the case, we intermittently activated the baroreflex with intravenous injections of phenylephrine. While phenylephrine increased MAP to a similar magnitude to that observed in response to chemoreflex activation, no changes in Fos-ir were observed in the different sub-regions of the PVN evaluated. This is in general agreement with previous studies showing either absence or very limited changes in PVN Fos-stained cells following phenylephrine infusions (Li and Dampney, 1994; Graham et al., 1995; Potts et al., 1997). Therefore, our results suggest that baroreflex activation due to the intermittent increase in MAP in response to chemoreflex activation did not contribute to Fos expression in the PVN. The bradycardic response to chemoreflex activation was of greater magnitude than that observed in response to phenylephrine. However, we have previously shown that bradycardic responses to chemoreflex activation are not mediated by the induced increase in arterial pressure (Haibara et al., 1995).

In conclusion, results from the present study indicate that intermittent activation of the chemoreflex in awake rats increases Fos expression in sympathetic PVN-RVLM neurons, as well as other (yet to be identified) neuronal populations within autonomic-related PVN subnuclei. Our findings suggest then that PVN-RVLM neurons constitute a likely substrate contributing to the sympathoexcitatory component of the chemoreflex, and support the notion that the PVN plays a critical role in the complex patterns of autonomic, respiratory and behavioral responses evoked by chemoreflex activation.

Methodological considerations

Several methodological aspects of this work deserve special attention. Firstly, the chemoreflex in this study was intermittently activated using cytotoxic hypoxia evoked by i.v. KCN administration. Previous studies from our laboratory demonstrated that chemoreflex activation with KCN mimicked the pattern and magnitude of cardiovascular responses elicited hypoxic hypoxia (5–7% O2), including an abrupt rise in arterial pressure accompanied by a marked bradycardic response, effects that were abolished by bilateral ligature of carotid body arteries (Barros et al., 2002). Therefore, the low concentration of KCN used in this study is a useful tool for a consistent and repetitive activation of the peripheral chemoreflex, and it was validated in several studies from our laboratory (Haibara et al., 1995, 1999; Machado and Bonagamba, 2005; Braga et al., 2007). Moreover, as discussed below, a similar increase in PVN Fos levels were recently reported using hypobaric hypoxia (Luo et al., 2000), moderate hypoxia (Berquin et al., 2000a, b) intermittent hypoxia (Greenberg et al., 1999). Altogether, these studies indicate that similarly to low oxygen, KCN treatment is a reliable tool to acutely activate the peripheral chemoreflex.

Secondly, cardiovascular responses elicited by KCN chemoreflex activation have been previously reported to be substantially different between anesthetized and conscious animals (Franchini and Krieger 1993). Thus, we believe that the use of intermittent chemoreflex activation in awake rats, as used in this study, more reliably represents the activation of specific subgroups of PVN neurons under more physiological condition.

The use of Fos as a marker of neuronal activation has been extensively characterized (Hirooka et al., 1997; Teppema et al., 1997; Chan and Sawchenko, 1998; Chan et al., 1998; Greenberg et al., 1999; Berquin et al., 2000a, 2000b; Bodineau and Larnicol, 2001; Hayward and Von Reitzenstein, 2002; Weston et al., 2003; Montero et al., 2006). Fos is the protein product of the early intermediate gene c-Fos and is part of the AP-1 transcription complex (Montero et al., 2006). Similarly to other brain regions, synthesis of Fos protein in the brainstem and hypothalamus starts from 15 to 30 min after the first stimulus, achieving a maximum expression 60 to 90 min after the stimulus onset (Chan and Sawchenko, 1998; Chan et al., 1998, Hoffman and Murphy, 2000; Weston et al., 2003). Furthermore, Fos protein synthesis has been shown to depend not only on the intensity of stimulus, but also on the interval between the stimulations (Chan et al., 1998; Hoffman and Murphy, 2000; Weston et al., 2003). In the present study (and in a paradigm similar to that used by Hayward et al. (2002) to evaluate chemoreflex-induced Fos expression in PAG neurons), the chemoreflex was intermittently stimulated every 3 min during a period of 30 min. Importantly, since a single injection of KCN failed to induce Fos expression in the PVN, our results most likely reflect Fos expression in response to repeated chemoreflex stimulations. While most of our studies were performed 60 min after the first KCN injection, similar results were observed in a subset of animals in which Fos was evaluated 90 min after the first stimulus. This is in agreement with previous studies from our laboratory showing similar increases in Fos-labeled cells in the NTS following 60 or 90 min after the first chemoreflex activation (Cruz et al., 2004).

It is important to take into account that the lack of Fos-ir is not a proof for the lack of involvement of a particular neuronal population in the studied stimulus. Thus, whether specific populations of PVN neurons are in fact inhibited by chemoreflex activation cannot be ruled out in the present study.

Finally, since Fluorogold could potentially be taken up by axons en passage (Weston et al J Comp Neurol 2003) (see however Schmued and Fallon, Brain Res 1986), injections in the RVLM could also have labeled direct PVN preautonomic projections to the spinal cord running through the injected area (Luiten et al 1985). Moreover, is likely that the injection site within the RVLM also contained respiratory neurons (Kanjhan et al., 1995). Thus, in addition to sympathetic premotor neurons, respiratory-related neurons could have been included in our studies.

Acknowledgements

In Brazil these studies were funded by FAPESP (01/01252-6 and 04/03285-7), CNPQ (522150/95-0). J.C.C. was supported by a CAPES fellowship. In USA, funding was provided by NIH HL68725 (JES). The authors are grateful to Drs. Patrícia M. de Paula and Gisela P. Pajolla for their important contribution to this study.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- PaP

Anterior parvocellular

- DC

dorsal-cap

- Fos-ir

Fos-immunoreactivity

- HR

heart rate

- LM

lateral magnocellular

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- MM

Medial magnocellular

- NTS

nucleus of solitarii tract

- OT

oxytocin

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus

- PaPo

posterior parvocellular

- KCN

potassium cyanide

- PAP

pulsatile arterial pressure

- RVLM

rostral ventrolateral medulla

- PaV

ventromedial parvocellular

- VP

Vasopressin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

J.C. Cruz, Department of Physiology, School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, 14049-900, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil

L.G.H. Bonagamba, Department of Physiology, School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, 14049-900, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil

B.H. Machado, Department of Physiology, School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, 14049-900, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil

V.C. Biancardi, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta GA USA.

J.E. Stern, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta GA USA.

REFERENCES

- Akine A, Montanaro M, Allen AM. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus inhibition decreases renal sympathetic nerve activity in hypertensive and normotensive rats. Auton Neurosci. 2003;31:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AM. Inhibition of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in spontaneously hypertensive rats dramatically reduces sympathetic vasomotor tone. Hypertension. 2002;39:275–280. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.104272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badoer E, Merolli J. Neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus that project to the rostral ventrolateral medulla are activated by haemorrhage. Brain Res. 1998;791:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badoer E. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and cardiovascular regulation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:95–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros RCH, Bonagamba LGH, Okamoto-Canesin R, Oliveira M, Branco LGS, Machado BH. Cardiovascular response to chemoreflex activation with potassium cyanide or hypoxic hypoxia in awake rats. Auton Neurosci. 2002;97:100–105. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao G, Randhawa PM, Fletcher EC. Acute blood pressure elevation during repetitive hypocapnic and eucapnic hypoxia in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:1071–1078. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.4.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berquin P, Bodineau L, Gros F, Larnicol N. Brainstem and hypothalamic areas involved in respiratory chemoreflex: a Fos study in adults rats. Brains Res. 2000a;857:30–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berquin P, Cayetanot F, Gros F, Larnicol N. Postnatal changes in Fos-like immunoreactivity evoked by hypoxia in the rat brainstem and hypothalamus. Brains Res. 2000b;877(2):48–159. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe TJ, Dunchen MR. Cellular basis of transduction in the carotid chemoreceptors. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:L 271–L 278. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.6.L271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodineau L, Larnicol N. Brainstem and hypothalamic areas activated by tissue hypoxia: Fos-like immunoreactivity induced by carbon monoxide inhalation in the rat. Neuroscience. 2001;108:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga VA, Soriano RN, Braccialli AL, de Paula PM, Bonagamba LGH, Paton JF, Machado BH. Involvement of L-glutamate and ATP in the neurotransmission of the sympathoexcitatory component of the chemoreflex in the commissural NTS of awake and in the working heart brainstem preparation. J Physiol. 2007;581(3):1129–1145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JY, Chen WC, Lee HY, Chan SH. Elevated Fos expression in the nucleus tractus solitarii is associated with reduced baroreflex response in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1998;32:939–944. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.5.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RK, Sawchenko PE. Organization and transmitter specificity of medullary neurons activated by sustained hypertension: implications for understanding baroreceptor reflex circuitry. J Neurosci. 1998;18:371–387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00371.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XQ, Du JZ. Hypoxia induces oxytocin release in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1999;20:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JC, Bonagamba LH, Stern JE, Machado BH. Fos expression in the NTS and PVN neurons in response to chemoreflex activation in awake rats. The Faseb Journal. 2004:A667–A668. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coote JH, Yang Z, Pyner S, Deering J. Control of sympathetic outflows by the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;2:461–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coote JH. The hypothalamus and cardiovascular regulation. In: Dun NJ, Machado BH, Pilowsky PM, editors. Neural mechanisms of cardiovascular regulation. 2004. pp. 118–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ET, Bohn MC, Sawchenko PE. Organization of adrenergetic inputs to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;292:651–667. doi: 10.1002/cne.902920413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchini KG, Krieger EM. Cardiovascular response of conscious rats to carotid body chemoreceptors stimulation by intravenous KCN. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1993;42:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90342-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg HE, Sica AL, Ruggiero DA. Expression of Fos in the rat brainstem after chronic intermittent hypoxia. Brains Res. 1999;816:638–645. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JC, Hoffman GE, Sved AF. c-Fos expression in brain in response to hypotension and hypertension in conscious rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;55:92–104. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00032-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haibara AS, Colombari E, Chianca DA, Jr, Bonagamba LG, Machado BH. NMDA receptors in NTS are involved in bradycardic but not in pressor response of chemoreflex. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1421–H1427. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.4.H1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haibara AS, Bonagamba LGH, Machado BH. Neurotransmission of the sympathoexcitatory component of chemoreflex in the nucleus tractus solitarii of unanesthetized rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R69–R80. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.1.R69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haibara AS, Tamashiro E, Olivan MV, Bonagamba LG, Machado BH. Involvement of the parabrachial nucleus in the pressor response to chemoreflex activation in awake rats. Auton Neurosci. 2002;101:60–67. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LF, Von Reitzenstein M. c-Fos expression in the midbrain periaqueductal gray after chemoreceptor and baroreceptor activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1975–H1984. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00300.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SG. Hypotalamic projection to cardiovascular centers of the medulla. Brain Res. 2001;894:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Polson JW, Potts PD, Dampney RAL. Hypoxia-induced Fos expression in neurons projecting to the pressor region in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neurosci. 1997;80:1209–1224. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman GE, Murphy AN. Anatomical markers of activity in hypothalamic systems. In: Humana Press Inc., editor. Neuroendocrinology in Physiology and Medicine. Totowa, NJ: 2000. pp. 541–552. [Google Scholar]

- Kanjhan R, Lipski J, Kruszewska B, Rong W. A comparative study of pre-sympathetic and Bötzinger neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) of the rat. Brain Res. 1995;699:19–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan H, Yamashita H. Connection of neurons in the regions of the nucleus tractus solitarius with the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: their possible involvement in neural control of the cardiovascular system in the rats. Brains Res. 1985;329:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90526-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooy DVD, Koda LY, Mcginty JF, Gerfen CR, Bloom FE. The organization of projections from the cortex, amygdala and hypothalamus to the nucleus of solitary tract in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;224:1–24. doi: 10.1002/cne.902240102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya N, Guyenet PG. NTS neurons with carotid chemoreceptor inputs arborize in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R1273–R1278. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukoff TL, Mactavish D, Harris KH, Jhamandas JH. Changes in blood volume and pressure induce Fos expression in brainstem neurons that projection to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Molecular Brains Res. 1995;34:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00142-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YW, Dampney RA. Expression of Fos-like protein in brain following sustained hypertension and hypotension in conscious rabbits. Neuroscience. 1994;161:613–634. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiten PG, ter Horst GJ, Karst H, Steffens AB. The course of paraventricular hypothalamic efferents to autonomic structures in medulla and spinal cord. Brain Res. 1985;329:374–378. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Kaur C, Ling EA. Hypobaric hypoxia induces Fos and neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression in the paraventricular and supraoptic nucleus in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000;296:145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado BH, Bonagamba LGH. Antagonism of glutamate receptors in the intermediate and caudal commissural NTS of awake rats produced no changes in the hypertensive response to chemoreflex activation. Auton Neurosc. 2005;117:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero S, Mendoza H, Valles V, Lemus M, Alvarez-Buylla R, De Alvarez-Buylla ER. Arginine-vasopressin mediates central and peripheral glucose regulation in response to carotid body receptor stimulation with Na-cyanide. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1902–1909. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01414.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivan MV, Bonagamba LH, Machado BH. Involvement of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the pressor response to chemoreflex activation in awake rats. Brains Res. 2001;895:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts PD, Polson JW, Hirooka Y, Dampney RA. Effects of sinoaortic denervation on Fos expression in the brain evoked by hypertension and hypotension in conscious rabbits. Neuroscience. 1997;77:503–520. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MK, Patel KP, Schultz HD. Differential role of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in modulating the sympathoexcitatory component of peripheral and central chemoreflexes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:789–797. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00222.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo JA, Koh ET. Anatomical evidence of direct projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract to hypothalamus amygdala and other forebrain structures in the rat. Brains Res. 1978;153:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafton AD, Ryan A, Badoer E. Neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus send collaterals to the spinal cord and to the rostral ventrolateral medulla in the rat. Brains Res. 1998;801:239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00587-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Share L, Levy MN. Carotid sinus pulse pressure, a determinant of plasma antidiuretic hormone concentration. Am J Physiol. 1966;211:721–724. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.211.3.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC, Fallon JH. Fluoro-Gold: a new fluorescent retrograde axonal tracer with numerous unique properties. Brain Res. 1986;377:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DW, Buller KM, Day TA. Role of ventrolateral medulla catecholamine cells in hypothalamic neuroendocrine cell responses to systemic hypoxia. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7979–7988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07979.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JE, Zhang W. Preautonomic neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus contain estrogen receptor beta. Brain Res. 2003;975:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker SD, Cunningham JT, Toney GM. Water deprivation increases Fos immunoreactivity in PVN autonomic neurons with projections to the spinal cord and rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1172–R1183. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00394.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE. Paraventicular nucleus: a site for integration of neuroendocrine and autonomic mechanisms. Neuroendocrinology. 1980;31:410–417. doi: 10.1159/000123111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyer KM. The central nervous organization of reflex circulatory control. In: Loewy AC, Spyer KM, editors. Central Regulation of Autonomic Functions. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa T, Dampney RA. AT(1) receptors mediate excitatory inputs to rostral ventrolateral medulla pressor neurons from hypothalamus. Hypertension. 1999;34:1301–1307. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.6.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teppema LJ, Veening JG, Kranenburg A, Dahan A, Berkenbosch A, Olievier C. Expression of Fos in the rat brainstem after exposure to hypoxia and to normoxic and hyperoxic hypercapnia. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:169–190. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<169::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston M, Wang H, Stornetta RL, Sevigny CH, Guyenet PG. Fos expression by glutamatergic neurons of the solitary tract nucleus after phenylephrine-induced hypertension in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:525–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.10663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Coote JH. Influence of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus on cardiovascular neurones in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat. J Physiol. 1998;513:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.521bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]