Abstract

A randomized clinical trail (RCT) employed a 12-month individualized cognitive/sensorimotor stimulation program to look at the efficacy of the intervention on 62 infants with suspected brain injury. The control group infants received the State-funded follow-up program provided by the Los Angeles (LA) Regional Centers while the intervention group received intensive stimulation using the Curriculum and Monitoring System (CAMS) taught by public health nurses (PHNs). The developmental assessments and outcome measures were performed at 6, 12 and 18 months corrected age and included the Bayley motor and mental development, the Home, mother–infant interaction (Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS) and Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS)), parental stress and social support. At 18 months, 43 infants remained in the study.

The results indicate that the intervention had minimal positive effects on the Bayley mental and motor development scores of infants in the intervention group. Likewise, the intervention did not contribute to less stress or better mother–infant interaction at 12 or 18 months although there were significant differences in the NCAFS scores favoring the intervention group at 6 months. There was a significant trend, however, for the control group to have a significant decrease over time on the Bayley mental scores. Although the sample was not large and attrition was at 31%, this study provides further support to the minimal effects of stimulation and home intervention for infants with brain injury and who may have more significant factors contributing to their developmental outcome.

Keywords: Newborn brain injury, Stimulation, Intervention, Outcome

Over the past 30 years, evidence has been accumulating for the neuro-plasticity of the human brain, allowing for recovery of important brain regions after injury. The organization of interconnected neurons, which make up neural systems, is not structurally or functionally rigid as once believed. Rather, individual neurons are able to modify their intrinsic membrane properties and the strength of their synaptic connections in response to varying levels of stimulation (du Plessis & Volpe, 2002; Kennedy & Marder, 1992). The newborn’s brain develops in a stepwise, organized fashion. It involves the unfolding of discrete, sequential embryonic processes that include the division, migration and differentiation of neural elements, dendritic arborization, and maturation of synapses. As the brain develops and matures, behavioral patterns emerge that reflect the integration of complex cerebral networks (Berger & Garnier, 1999; Volpe, 2000).

Several factors are implicated in the etiology of brain injury. The most common cause is hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) which has been associated with neuronal reorganization. Current data suggest that about 2–5 of 1000 live term births experience hypoxic–ischemic brain injury or intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) of those, 30–40% die during the newborn period and 20–50%; of those, who survive develop significant neurological impairments including cerebral palsy, seizures, mental retardation, and learning disabilities (Berger & Garnier, 1999; Bracwell & Marlow, 2002; de Dois, Maya, & Vioque, 2001).

Animal research has indicated that in normal rats without brain damage the quality of the environment can determine brain size. For example, rats maintained in an environmentally enriched environment had heavier cerebral cortices and increased brain levels of acetylcholine compared to rats reared in impoverished environments (Bennett, Rosenzweig, & Diamond, 1969). Likewise, studies with human infants have supported the benefits of intervention/stimulation on developmental outcome of children from impoverished backgrounds, as well as on high-risk children such as premature infants and drug-exposed infants (e.g. Fazzi et al., 1997; Norr et al., 2003; Parker, Zahr, Cole, & Brecht, 1992; Schuler, Nair, & Kettinger, 2003; Zigler & Muenchow, 1992). Therefore, a rich environment with intensive stimulation may well allow infants with brain injury to recover.

Specific studies on the efficacy of intervention on the outcome of children with brain injury are few, mostly due to the difficulty in conducting such studies and in diagnosing brain injury (Butler et al., 1999). Only five such studies are found in the literature. One study used auditory–tactile–visual–vestibular intervention which began in the NICU and continued for 2 months after discharge on 37 infants with severe central nervous system injury. Although the intervention group had better Bayley mental and motor scores at 12 months, the differences were not significant (Nelson et al., 2001). An earlier study by Piper et al. (1986) failed to find any positive effects of an early neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT) by a physical therapist on 134 infants who had experienced birth asphyxia, central nervous system disorders or were who were premature. The intervention, which included parental teaching, positioning and stimulation for 12 months, did not significantly alter the neurodevelopmental outcome of infants as measured on the Wilson Developmental Reflex Profile, the Milani-Comaretti Motor Development screening test or the Grifiths Mental Development Scale. Likewise, there were no differences in the developmental quotients of 80 very low birth weight infants (half of whom were neurologically impaired) assigned to a NDT or a control group at 1 year or at 6 years of age (Goodman, Rothberg, Houston-McMillan, Cooper-Cartwright, & van der Velde, 1985; Rothberg, Goodman, Jacklin, & Cooper, 1991). A study using an individualized sensorimotor intervention at 3 months after discharge on 58 medically fragile infants, some of whom had intraventricular hemorrhage, followed by an intervention based on the Curriculum and Monitoring System (CAMS) at 18 months also failed to show any benefits of the intervention at 30 months. This latter study assessed children on the Batelle Developmental Inventory, the Stanford-Binet Screening Test and Toddler Temperament Scale (Boyce, Smith, Immel, Casto, & Escobar, 1993). A recent study in Japan (Ohgi, Fukuda, Akiyama, & Gima, 2004) used developmental support on a group of 23 high-risk infants with cerebral injuries. At 44 weeks post-conceptual age, infants in the intervention group (n = 12) had significantly better behavioral scores and higher Bayley scores, albeit not significantly higher, than the control group.

Except for the study by Nelson et al. (2001) and Ohgi et al. (2004) both of which had a small sample size, the intervention was initiated after discharge or at 3 months which could have had a negative impact on the results. While early intervention in the above cited studies did not improve motor or mental outcome for infants at neurological risk, nor was there any effect on the incidence of cerebral palsy, most studies which have focused on specific interventions for children with cerebral palsy have noted positive results. For example, a study on 26 young children with cerebral palsy using an intervention based on the principles of conductive education found that the intervention had positive effects on motor development (Liberty, 2004). Likewise a non-randomized study using the “Vojta Method”, which is an extensive family oriented physiotherapy program found a positive effect on the motor outcome of 10 infants with cerebral palsy at 5 years (Kanda, Pidcock, Hayakawa, Yamori, & Shikata, 2004). In contrast an earlier study by Palmer, Shapiro, and Capute (1989), which randomly assigned 48 infants with mild to severe spastic diplegia to either a NDT alone or a NDT plus stimulation intervention, found that motor and mental development measured on the Bayley scales favored the stimulation group after 12 months of treatment.

With regards to home intervention and broad based stimulation with high-risk and premature infants, most researchers agree that overall intervention provides short- and long-term benefits. Positive influences on cognitive, behavioral and social development, on parent–child relationships, on school attendance and performance have been documented (Drummond, Weir, & Kysela, 2002; Dumaret, 2003).

Based on the above and acknowledging that few researchers have attempted to assess the efficacy of stimulus repetition or an enriched environment on the functional recovery potential of infants with suspected brain injury, the goals of this study were to (1) enhance cognitive and sensorimotor development in infants with hypoxic brain injury (HIE); (2) improve parent–infant interaction; and (3) reduce the stress experienced by mothers. The study also differed from earlier studies in that is attempted to apply specific criteria to the diagnosis of HIE and to use MRI as a tool for evaluating infants with brain injury.

1. Methods

1.1. Study design

This randomized blinded clinical study tested the efficacy of home-based cognitive and sensorimotor intervention on the development of infants who have sustained a brain injury.

1.2. Setting

The intervention and outcome variables were conducted and assessed in the homes of infants who were diagnosed with brain injury before their discharge from one of the four hospitals in Southern California. The MRIs and the neurological assessments were performed at the pediatric clinics at UCLA. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from all hospitals that agreed to participate in the study. All parents who agreed to be in the study signed an informed consent.

1.3. Subjects

The initial sample consisted of a total of 62 families with infants who had sustained a brain injury. Infants were recruited when they met the following criteria: (1) a brain injury based on the criteria established by the University of California at San Francisco group studying brain asphyxia (Miller et al., 2002), (2) abnormal findings on a neurological examination by the neurologist at each facility (performed as soon as the brain injury was suspected within 1 or 2 days after birth), (3) an abnormal MRI or EEG and (4) born after 28 weeks gestation (see Table 1 for details). Mothers were between 17 and 40 years of age, from different socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds, and willing to participate actively in the intervention if they were in the experimental group. Infants were excluded if they had Grade IV IVH with periventricular leukomalacia or evidence of severe cortical destruction or atrophy (see Table 1). Exclusion criteria were based on the severe long-term consequences and higher mortality rates for infants with these conditions, or if those conditions prevented the acquisition of magnetic resonance imaging (ACOG, 1998; Nelson et al., 2001). At 18 months, 43 infants remained in the study; 2 died (one form each group), 3 were dropped from the study due to non-compliance with the intervention and 14 were lost to follow-up. There were no differences in attrition rates between the control group and the experimental group and no differences in the background characteristics between the group lost to attrition and the group retained.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Children must have at least three or more of the following characteristics: |

| 1. pH at <7.00 per cord blood and/or a base deficit of −10 meq/1 or more, or an arterial pH of <7.1 within 72 h of birth |

| 2. Intrapartum distress: as evidenced by placenta abruption, thick stained meconium amniotic fluid and abnormal fetal heart rate patterns (a pattern of late decelerations with no accelerations and bradycardia <100 beats per minute) |

| 3. Intubation and resuscitation in the delivery room or within an hour after birth |

| 4. Abnormal neurological exam in the NICU |

| 5. Abnormal head ultrasound, EEG, MRI or CT scan |

| 6. Intraventricular hemorrhage: Grades III and IV without perventricular leukomalacia or evidence of severe cortical destruction or atrophy |

| 7. Seizure activity anytime during NICU stay |

| 8. Apgar <5 at 5 min or beyond that of birth (e.g., 10 min Apgar score would be acceptable replacement for 5 min appraisal) |

| Children may not have any of the following conditions: |

| 1. Cochlear implant or pacemaker implants |

| 2. Congenital orthopedic anomalies requiring surgery for implants and wires and corrections (due to limited ROM) |

| 3. Congenital anomalies of the CNS rare genetic conditions and syndromes (e.g., 13 trisomy 18, trisomy 21, fragile X syndrome) |

| 4. Severe structural or multiple congenital cardiac anomalies requiring surgery |

| 5. Genetic syndromes indicating inborn errors in metabolism, e.g. phenylketonuria |

| 6. Grade IV with perventricular leukomalacia or evidence of severe cortical destruction or atrophy |

1.4. Intervention

The intervention used the Curriculum and Monitoring System (CAMS) method which consists of mental and sensorimotor stimulation (CAMS, 1992). This program was taught to mothers by trained public health nurses (PHNs). The CAMS has been used by researchers at the Utah State University (Casto & White, 1993) and consists of five programs: Cognitive, Language, Motor, Self-Help, and Social Skills programs. The Self-Help and Social Skills programs were not used in this study due to the length of the entire program and based on the fact that the nurses were providing extensive and individualized care to the families. The program consists of more than 100 defined and illustrated cognitive, motor, and language activities aimed at enhancing development of children from birth to 5 years. Although very specific and detailed, the CAMS was individualized based on the progress of each child and the needs of each mother. The PHNs recorded how many minutes mothers provided the intervention and coached them to adhere to daily 20-min stimulation activities.

In addition to teaching the CAMS, the PHNs supported and empowered mothers in the care of their infants. Research has consistently found that when mothers feel supported and empowered, they are more likely to comply with intervention and to be motivated to continue in the study (Cochran, 1988; Landry, Smith, & Swank, 2003).

1.4.1. Outcome measures

All dependent variables, except for the MRI were obtained by a trained research assistant (RA) who was blinded to group assignment and the objectives of the study. The MRI was performed by the co-investigator who was blind to group assignment at the UCLA, neuroimaging department. The RA was trained to a reliability of 90% on all the assessment scales. The scales have been used in previous studies and have established validity and reliability with White-Americans, African-Americans and Latinos. The RA visited the mothers in their homes at discharge from the NICU, and at 6, 12 and 18 months corrected age. During these visits the RA performed the Bayley assessment scales, the mother–infant interaction scales and the assessment of the home environment (HOME). Mothers filled out two questionnaires: the social support scale and the perceived stress scale. Each visits lasted between 1.5 and 2 h.

1.4.2. Infant outcome measures The Bayley Assessment Scales and the MRI

1.4.2.1. Motor and mental development

The Bayley Scales of Infant Development are the most widely used standardized measures of cognitive and motor development in infancy and early childhood (Bayley, 1969). The Bayley developmental evaluation provides two measures; the Mental Development Index (MDI) and the physical development Psychomotor Developmental Index (PDI). The mean for the MDI at baseline in this study for the control group was 89.73 ± 15.0 and for the experimental it was 83.21 ± 18.3. For the PDI at baseline, the control scored at 89.53 ± 17.9 while the experimental scored 85.63 ± 19.1.

1.4.2.2. MRI

All infants underwent a structural MRI at base line and at 18 months. All MR imaging was performed on a 1.5T GE (Milwaukee, MI, USA) MR scanner (Version 5.8), with EPI capable gradient strengths. A saggital scout scan was acquired, second, a 3D set of axial T1-weighted images was acquired followed by T2-weighted FAST Spin Echo imaging. A total of 2 min of scanning time was used for two sets of 20 s of scanner noise and 40 s of stimulation. All images were transferred via secure internet, to off-line computers for image processing, and reading by a radiologist who was not aware of any clinical findings. Of the initial 62 infants, 39 had scans that could be read and analyzed for this study. Two scans had motion artifacts and could not be read accurately. The MRI scans were examined by one certified radiologist at UCLA and were labeled as either normal or abnormal.

1.4.3. Maternal measures mother–infant interaction, and parental stress

1.4.3.1. Mother–infant interaction

The Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS) and Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) were used to assess mother–infant interaction in this study, (Barnard & Bee, 1983; Barnard et al., 1987). The scales consist of 149 items that are answered on a yes/no form and yield a summary score.

1.4.3.2. Parenting stress

Parental stress was assessed using the Parenting Stress Index (Abiddin, 1986). This questionnaire was designed to assess the degree of stress related to parenting. The short form of the PSI was used which has 36 items which the parents complete by rating on a 5-point scale how much they agreed or did not agree with the statement. The PSI has established reliability and validity (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000).

1.4.4. Intervening variables: the HOME, social support, neurological examinations and background characteristics

1.4.4.1. The home environment

The Caldwell HOME inventory was used to assess the home environment (Caldwell & Bradley, 1978). This is a widely used scale that has been significantly correlated with the child’s cognitive ability at 3 years of age.

1.4.4.2. Social support

Social support was assessed using the Perceived Social Support Scale by Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, and Farley (1988). The 12-item scale of Perceived Social Support (PSS) assesses the degree of satisfaction with the support received from family members, friends and significant others.

1.4.4.3. Neurological examinations

Neurological examinations were performed by one experienced pediatric neurologist blinded to the MRI findings, the clinical course of the infants or the objectives of the study. The examinations took place at UCLA at four points in time: at baseline, and at 6, 12 and 18 months corrected age. The neurological examinations recorded items such as head lag, limb tone and movement, reflexes, developmental delays, vision and hearing impairments and head circumference. Thee results of the neurological examinations were classified as normal or abnormal by the neurologist.

1.4.4.4. Demographic variables

Information on both mothers and infants were obtained from the medical records and were documented on special forms. Information obtained included the background of the parents, such as income, education and number of children as well as the medical history of both the mother and the infant.

1.4.5. Procedure

Infants were recruited from four hospitals in Southern California after they had been suspected to have sustained a brain injury and after their parents signed the consent form. Infants were randomly assigned to an experimental or a control group. The trained PHNs visited the experimental families twice a week for 1 month, weekly until the infant was 4 months and then every other week until the infant was 12 months old. All infants received a neurological assessment by one neurologist at baseline, at 6, 12 and 18 months, to verify the relevancy of the intervention to each child’s neuropathy for the experimental group and as a comparison for the control group. The parents in the control group did not receive any special training or visitation by trained PHNs; however, they received the standard care provided by the Los Angeles regional centers.

1.4.6. Statistical analysis

Summary statistics for all variables at each of the four time points were obtained. A two-group statistical comparison of the variables was performed at baseline using the two-sample Wilcoxon test and the chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Wilcoxon p-values were used instead of the t-test p-values to get non-parametric estimates since the values of the variables were not always normally distributed. Analysis of variance looked at the effect of intervention on the outcome variables: MDI, PDI, NCAFS, NCATS and the PSI at 6, 12 and 18 months. In addition, ANCOVAS with APGARS at 5 min as a covariate were performed to examine the effect of both intervention and APGAR scores on the outcome variables. Finally, graphs showing the mean profiles of these outcome variables at the various time points were created. Due to attrition, the sample size decreased over time and the sample size was different at each time period. The graphs show the number of participants at each assessment period.

2. Results

The characteristics of the sample are described in Table 2. Sixty-eight percent of the sample was of Hispanic origin, which reflects the birth rates of Los-Angeles, and 60% had prenatal care in the second trimester. Although randomization was used, the experimental group had lower APGAR Scores at 5 min, albeit not significant (p = 0.07). All other background characteristics of experimental and control groups, as well as the intervening variables showed no differences between groups (Table 2). Eleven infants (6, intervention and 5 control) manifested abnormal neurological findings at 12 and 18 months. Abnormal findings included hemiparesis, hemiplegia, decreased muscle tone, scissoring, choreoathetosis, microcephaly, decreased vision and spastic cerebral palsy. Not all infants had MRI scans at baseline due to difficulties such as the parents not being able to transfer unstable infants and scheduling problems. Forty-one infants had scans performed at baseline, 39 of which were readable; of those, 26 (67%) were abnormal (14 intervention and 12 control), 2 infants (5%) had normal MRI results at baseline and had abnormal neurological findings that persisted till 18 months and 11 out of the 39 (28%) had normal MRI results yet manifested abnormal neurological signs at baseline and at 6 months but those disappeared at 18 months. At 18 months, 32 scans were performed, 25 were abnormal (13, intervention and 12 control).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the sample

| Characteristic | Control (30) (mean ± S.D.) | Experimental (32) (mean ± S.D.) | Wilcoxon p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight | 1882.83 ± 1393.42 | 1538.41 ± 893.34 | 0.74 |

| Gestational age | 30.98 ± 2.06 | 30.03 ± 2.72 | 0.72 |

| APGAR score—1 min | 6.09 ± 1.98 | 4.82 ± 2.69 | 0.11 |

| APGAR score—5 min | 7.74 ± 1.39 | 6.64 ± 2.22 | 0.07 |

| Male to female ratio | 18/12 | 20/12 | 0.84 |

| Prenatal care in the second trimester | 18 of 30 | 25 of 32 | 0.20 |

| Maternal age | 25.41 ± 1.04 | 29.1 ± 1.2 | 0.05 |

| Maternal education: Grade 12 or more | 18 of 30 | 17 of 32 | 0.77 |

| Days in hospital | 69.5 ± 9.03 | 57.8 ± 5.2 | 0.76 |

| Hispanic (n) | 21 | 22 | 0.92a |

| Caucasian (n) | 3 | 4 | 0.76a |

| African American (n) | 3 | 4 | 0.76a |

| Other ethnic group (n) | 3 | 2 | 0.94a |

Note that these chi-square test p-values should be used with caution since the counts were low (less than 5).

2.1. Mental and motor development

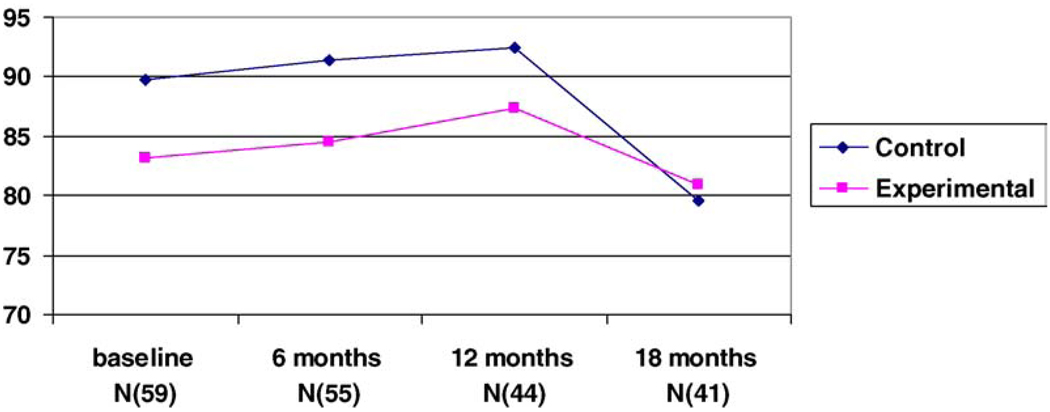

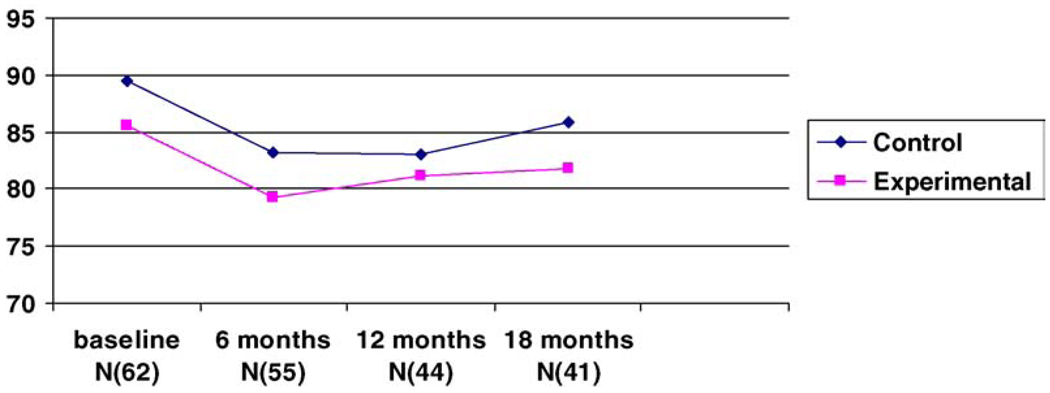

The results of the ANOVA indicated that there were no differences between groups on the Bayley mental scores (MDI) and the Bayley motor scores (PDI) at 6, 12 or 18 months. As noted in Fig. 1 and Fig 2, both mental and motor scores for the experimental and control groups declined with time irrespective of group assignment. However, the drop was significant for the control group on the MDI which declined from a baseline mean of 89.7 ± 15.0 to a mean of 79.5 ± 15.4 at 18 months (F(2/39) = 6.23, p = .042). It is worth noting that the intervention group started off with lower mental and motor scores albeit, not a significant difference. The scores on the Bayley scales were extremely variable with scores ranging from below 50 to 112. Three infants from the experimental group and one from the control group scored below 50 on the MDI and the PDI scales. We analyzed our results excluding these four infants to ascertain whether the outliers had a negative effect on outcome. The results did not show any difference when these infants were excluded. Furthermore, the significance of the 5 min APGAR scores in determining outcome and the difference between groups in the APGAR scores in this study (p = 0.07) were sufficient to warrant ANCOVA with APGAR scores at 5 min as the covariate. The results of the ANCOVA were not different than the results reported above.

Fig. 1.

Bayley mental scores for the four time periods.

Fig. 2.

Bayley motor scores for the four time periods.

2.2. Mother–infant Interaction

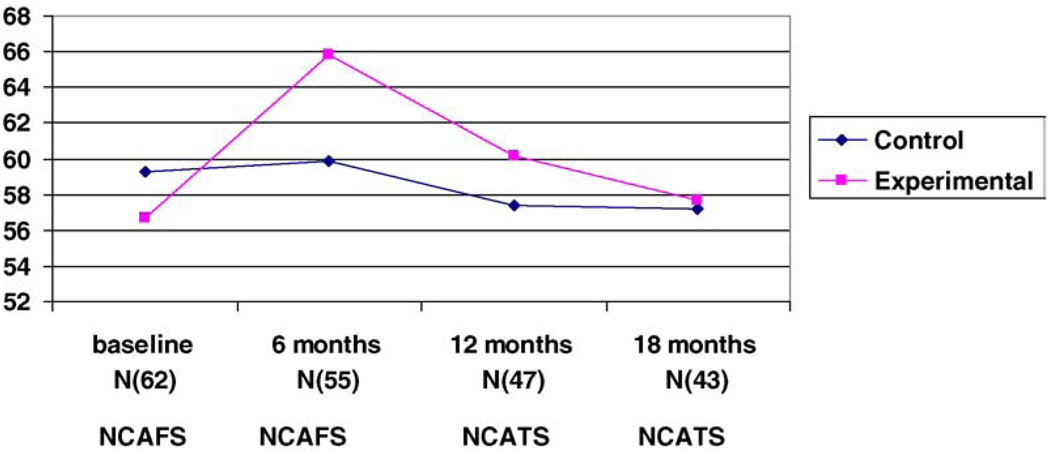

Likewise there were no differences between groups on the NCATS scores at 12 and 18 months (Fig. 3). Group assignment had no effect on the how the mothers interacted with their infants at the 12- and 18-month follow-up periods. The only significant finding was that at 6 months the NCAFS scores favored the experimental group (F(2/53) = 3.35, p = 0.03).

Fig. 3.

NCAFS and NCATS scores for the four time periods.

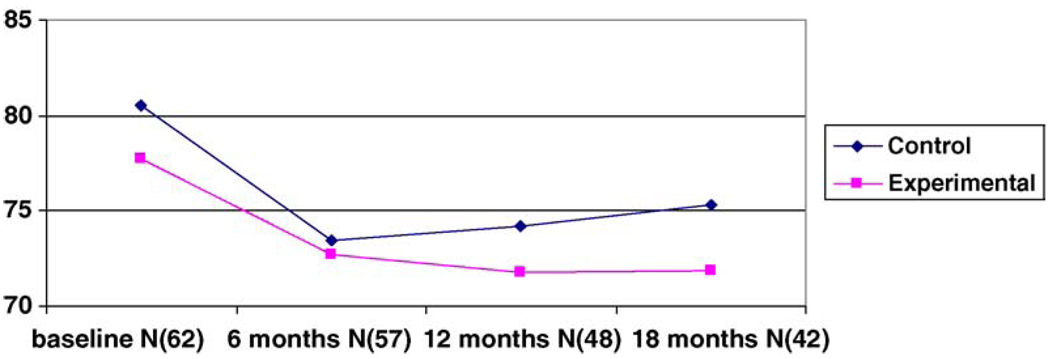

2.3. Parental stress

There were no differences between groups on the PSI scale at the three time periods. Fig. 4 describes the changes in the stress scores for both groups over time. Both groups had significantly less stress over the three time periods, with the control group manifesting more stress at 18 months with the difference approaching significance, p = 0.06.

Fig. 4.

PSI scores over the four time periods.

In general, there was no major advantage to the intervention provided in this study. The broad form of intervention using the CAMS and the intense support provided to mothers by the PHNs did not improve the developmental outcome of infants with suspected brain injury at 18 months. These results were observed despite the fact that mothers in the experimental group reported satisfaction with the care provided by the PHNs and did not want to end their relationships with the nurses once the study was completed.

3. Discussion

Although a number of medical interventions have been attempted with infants with brain injury, there is a dearth of research on the efficacy of stimulation or parental support. The rationale for this study was that repeated stimulation by mothers in the homes of infants with suspected brain injury will enhance their motor and mental functioning and will improve parental stress and mother infant interaction. Because the performance of children in both groups on the Bayley mental and motor scores, as well as their neurological outcome and MRI findings were not significantly different at 18 months suggests that there may be other factors that influence the long-term outcomes of infants with brain injury. Several explanations to these findings are plausible.

Numerous factors may have contributed to the outcome of infants with brain injury and which may have been more influential than the intervention. Such factors include, but are not limited to, the type and timing of the brain injury, the method of treatment or intervention received in the NICU and the actual stimulation provided by mothers. Our findings support previous results that found no positive effects of intervention on the neuro-developmental outcome of infants with brain injury at 1 year (Nelson et al., 2001; Piper et al., 1986). The main determinant of Bayley scores in the study by Nelson et al. (2001) was the presence of PVL. Although we excluded infants with PVL and severe asphyxia in our study, infants remained extremely sick and fragile with medical conditions which may have prohibited them from benefiting from intervention. Earlier studies that have provided support to the benefits of intervention were conducted on older children with diagnosed motor delay or cerebral palsy (Kanda et al., 2004; Liberty, 2004; Trahan & Malouin, 2002) rather than to infants at risk for neuro-developmental delay (e.g. Piper et al., 1986). Intervention may therefore be more effective when focused on a specific group of children with well-defined diagnoses, rather than on infants with a wide variation of diagnoses and illnesses.

Another explanation may be that the intervention provided to this sample, which was mostly of Hispanic origin, may not have been culturally sensitive. An earlier study by the author using a similar approach of intervention by PHNs found no effect of intervention on a group of high-risk premature infants form Latino backgrounds (Zahr, 2000). Latino families may experience more stress and difficulty in coping with an infant with a brain injury and a visit by a PHN may actually add to their anxiety and inability to cope. Although the mothers in our intervention expressed their gratitude to the PHNs, this may not have alleviated their stress in coping with such visits. Mothers may have felt that the intervention was more of a burden than a benefit to them. Indeed, it has been suggested that offering mothers formal support when they do not express such a need may have a negative impact on their adjusting to their high-risk infants (Affleck, Tennen, Rowe, Roscher, & Walker, 1989).

Another possible explanation for the lack of statistical support for our intervention may be that more intensive intervention may be required for such infants. A 1–2 h weekly visit by PHNs may not be sufficient to ameliorate the neurological impairments or motor and mental deficits of these children. Furthermore, although the nurses recorded how many minutes the mothers provided the stimulation and were consistent in making sure that the mothers were complying with the treatment, in reality the mothers may not have been compliant due to other stressors they were experiencing.

The lack of a true control group is another issue that needs to be mentioned. Ethical considerations prohibit the lack of referral and treatment of infants in need of supportive services in addition to the fact that the control group in this study was receiving the State-funded follow-up program provided by the Los Angeles Regional Centers. Although, the State-funded program was not as intense as the intervention provided in this study and was often not initiated in the early neonatal period, it may still have contaminated the results.

Previous researchers have argued the importance of the timing of intervention (Blauw-Hosper & Hadders-Algra, 2005; Piper et al., 1986). Intervening may need to be initiated prior to the discharge of infants, especially for high-risk premature infants who compromised 80% of our study sample. A previous study by the author and colleagues (Parker et al., 1992), which provided developmental intervention to mothers when their premature infants were still in the NICU, showed that the experimental-group infants performed more optimally on the Bayley mental scale and motor scores at 4 and 8 months of age.

Finally, although we attempted to quantify brain injury by using specific clinical criteria as well as EEG or MRI findings, not all infants recruited into the study were noted to have a brain injury by MRI results (23% had normal MRI findings after discharge). Several explanations could be offered namely that the clinical indicators or histories were not accurate or that the MRIs do not always pick subtle brain insults as evident in the 2 infants in our study that had normal scans at baseline yet significant neurological deficits at 18 months. It is worth noting that none of the MRIs were obtained in the early neonatal period, thus eliminating the possibility that swelling and other abnormal findings had not had time to appear.

Although the incidence of brain injury is quite low, the long-term consequences in terms of health, growth and development are appalling. Thus, the results of this study should not hinder researchers from investigating other modes of intervention taking into consideration the limitations of this study. The sample size was relatively small although larger than most intervention studies with similar populations and the 30% attrition rate may have influenced findings. Attrition is a serious problem with longitudinal studies. Although we attempted to limit it by establishing a rapport with families and gaining their confidence, we were not always successful. As noted, there were no differences in the characteristics of families who were lost to follow-up compared to those retained which limits the effect of differential attrition. Furthermore, there are many factors that could have influenced outcome and which we have not assessed in this study. One such factor is the actual compliance of mothers in the intervention group with the CAMS program. It is one thing to intervene and teach mothers, and another to verify that the teaching has actually been implemented. It is also worth mentioning that any slight initial benefits to the intervention in this study seemed to diminish with time indicating that intervention programs should not be considered successful unless the outcomes are measured over an extended time period.

Although this study did not find positive benefits to intervention for children with suspected brain injury, it is nevertheless important for researchers and health providers to continue to design new and efficacious interventions to ameliorate detrimental neurodevelopmental consequences. We also believe that several studies with larger groups of infants should be conducted before a definite answer to the question of early intervention with infants suspected with brain injury is answered. This is especially true as we continue to learn and yet are puerile in our knowledge about the newborn brain, its plasticity and the potential value of therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the NICHD, R01 and a grant from NIH. MO1RR00425. The authors wish to thank all the hospitals which participated in this study UCLA, Harbor Medical Center, Children’s hospital of Los Angeles and California Medical Center. We also greatly appreciate the help and commitment of all the nurses, physicians and research assistants who made this study possible.

References

- Abiddin RR. Parenting stress index. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Inappropriate use of the terms fetal distress and birth asphyxia. 1998 Committee Opinion, number 174. [Google Scholar]

- Affleck G, Tennen H, Rowe J, Roscher B, Walker L. Effects of formal support on mothers’ adaptation to hospital-to-home transition of high-risk infants: The benefits of costs of helping. Child Development. 1989;60:408–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard K, Bee M. The impact of temporally patterned stimulation on the development of preterm infants. Child Development. 1983;54:1156–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard K, Hammond M, Sumner G, Karg R, Johnson-Crowley N, Snyder C, et al. Helping parents with preterm infants: Field test of a protocol. Early Child Development and Care. 1987;27:255–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant development. The Psychological Corporation; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett EL, Rosenzweig MR, Diamond MC. Rat brain effects of environmental enrichment on wet dry weights. Science. 1969;21:825–826. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3869.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R, Garnier Y. Pathophysiology of perinatal brain damage. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;30:107–134. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauw-Hosper CH, Hadders-Algra M. A systematic review of the effects of early intervention on motor development. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2005;47(6):421–432. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce GC, Smith TB, Immel N, Casto G, Escobar C. Early intervention with medically fragile infants: Investigating the age-at-start question. Early Education Development. 1993;4:290–305. [Google Scholar]

- Bracwell M, Marlow N. Patterns of motor disability in very preterm children. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2002;4:241–248. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, McCarton CM, Cassey PH, McCormick MC, Bauer CR, Bernbaum JC, et al. Early intervention in low birth weight premature infants. Results through age 5 years from the Infant Health and Development. Journal of American Medical Association. 1994;22(7):126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Butler C, Chambers H, Goldstein M, Harris S, Leach J, Campbell S, et al. Evaluating research in developmental disabilities: A conceptual framework for reviewing treatment outcomes. Developmental Medicine in Child Neurology. 1999;41(1):55–59. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell B, Bradley R. Home observation for measurement of the environment. Little Rock: University of Arkansas; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- CAMS. A curriculum based assessment and intervention program for infants and preschoolers. Logan: Utah State University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Canty-Mitchell J, Zimet GD. Psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:391–400. doi: 10.1023/A:1005109522457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casto G, White K. Longitudinal studies of alternative types of early intervention: Rationale and design. Early Education and Development. 1993;4:224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran M. Parental empowerment in family matters: Lessons learned from a research program. In: Powell DR, editor. Parent education as early childhood intervention: Emerging directions in theory, research and practice. NJ: Ablex; 1988. pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- de Dois G, Moya M, Vioque J. Risk factors predictive of neurological sequlue in term newborn infants with perinatal asphyxia. Revista de Neurologia. 2001;32:210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond JE, Weir AE, Kysela GM. Home visitation programs for at-risk young families. A systematic literature review. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2002;93(2):153–158. doi: 10.1007/BF03404559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumaret AC. Early intervention and psycho-educational support: A review of the English language literature. Archives de Pediatrie. 2003;10(5):448–461. doi: 10.1016/s0929-693x(03)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis AJ, Volpe J. Perinatal brain injury in the preterm and term newborn. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2002;15(2):151–157. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzi E, Orcesi S, Telesca C, Ometto A, Rondini G, Lanzi G. Neurodevelopmental outcome in very low birth weight infants at 24 months and 5 to 7 years of age: changing diagnosis. Pediatric Neurology. 1997;17(3):240–248. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(97)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M, Rothberg AD, Houston-McMillan JE, Cooper PA, Cartwright JD, van der Velde MA. Effect of early neurodevelopmental therapy in normal and at-risk survivors of neonatal intensive care. Lancet. 1985;4:1327–1330. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MB, Marder E. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of neuronal plasticity. In: Hall Z, editor. Molecular neurobiology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1992. pp. 463–494. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda T, Pidcock FS, Hayakawa K, Yamori Y, Shikata Y. Motor outcome differences between two groups of children with spastic diplegia who received different intensities of early onset physiotherapy followed for 5 years. Brain Development. 2004;26(2):118–126. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(03)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR. The importance of parenting during early childhood for school-age development. Development in Neuropsychology. 2003;24:559–561. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2003.9651911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberty K. Developmental gains in early intervention based on conductive education by young children with motor disorders. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2004;27(1):17–25. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SP, Weiss J, Barnwell A, Ferriero DM, Latal-Hajnal B, Ferrer-Rogers A, et al. Seizure-associated brain injury in term newborns with perinatal asphyxia. Neurology. 2002;26(584):542–548. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MN, White-Traut RC, Vasan U, Silvestri J, Comiskey E, Meleed RP, et al. One-year outcome of auditory-tactile-visual-vestibular intervention in the neonatal intensive care unit: Effects of severe prematurity and central nervous system injury. Journal of Child Neurology. 2001;16:493–498. doi: 10.1177/088307380101600706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norr KF, Crittenden KS, Lehrer EL, Reyes O, Boyd CB, Nacion KW, et al. Maternal and infant outcomes at 1 year for a nurse-health advocate home visiting program serving African Americans and Mexican Americans. Public Health Nursing. 2003;20(3):190–203. doi: 10.1046/j.0737-1209.2003.20306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgi S, Fukuda M, Akiyama T, Gima H. Effect of an early intervention programme on low birthweight infants with cerebral injuries. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2004;40(12):689–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer FB, Shapiro BK, Capute AJ. Physical therapy for infants with spastic diplegia. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1989;31(1):128–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SJ, Zahr LK, Cole JG, Brecht ML. Outcome after developmental intervention in the neonatal intensive care unit for mothers of preterm infants with low socioeconomic status. Journal of Pediatrics. 1992;120:780–785. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper MC, Kunos VI, Willis DM, Mazer BL, Ramsay M, Silver KM. Early physical therapy effects on the high-risk infant: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1986;78(2):216–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg AD, Goodman M, Jacklin LA, Cooper PA. Six-year follow-up of early physiotherapy intervention in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1991;88(3):547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler ME, Nair P, Kettinger L. Drug-exposed infants and developmental outcome: effects of a home intervention and ongoing maternal drug use. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent medicine. 2003;157(2):133–138. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trahan J, Malouin F. Intermittent intensive physiotherapy in children with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2002;44(4):233–239. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe J. Neurology of the newborn. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zahr LK. Home based intervention after discharge for Latino families of low birth weight infants. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2000;21(6):448–463. [Google Scholar]

- Zigler E, Muenchow S. Head start. New York: Harper Collins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]