Abstract

The parathyroid glands are an infrequent target for autoimmunity; the exception being in the autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1, where autoimmune hypoparathyroidism is the rule. Antibodies that are directed against the parathyroid cell-surface calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) have recently been recognised to be present in the serum of patients with autoimmune hypoparathyroidism. In some individuals, these anti-CaSR antibodies have also been shown to produce functional activation of the receptor, suggesting a direct pathogenic role in hypocalcemia. Additionally, a few hypercalcemic patients with autoimmune hyperparathyroidism owing to anti-CaSR antibodies that inhibit receptor activation have now been identified. Other novel parathyroid autoantigens are starting to be elucidated. These findings suggest that new approaches to treatment, such as CaSR antagonists or agonists (calcilytics/calcimimetics) may be worthwhile.

Keywords: Parathyroid, calcium-sensing receptor, CaSR, autoantibody, anti-parathyroid antibody, ant-CaSR antibody, autoimmune, hypoparathyroidism, autoimmune hypocalciuric hypercalcemia

Introduction

Autoimmunity is an important cause of hypoparathyroidism, either as an isolated endocrinopathy or as a component of autoimmune polyglandular syndromes (e.g., APS1 and 2) (see chapter 11) [1,2]. In Norway, the prevalence of APS1, comprising candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, and Addison's disease, which can be accompanied by chronic active hepatitis, alopecia and primary hypogonadism, is about 1:90,000. In some genetically more homogeneous populations, it is more common, with a prevalence of 1:600-1:9000 in Iranian Jews and 1:25,000 in Finns [2]. The first direct evidence in support of an autoimmune basis for idiopathic hypoparathyroidism (IH) was provided by Blizzard, et al. in 1966, who identified anti-parathyroid antibodies in patients with presumed autoimmune hypoparathyroidism (AH) [3]. The identity of the parathyroid antigen(s) remained uncertain for 30 years. The cloning and characterization of the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) in 1993 [4] (Fig 1) as the molecular mechanism by which parathyroid cells recognize and respond to changes in the extracellular calcium concentration (Ca2+o) identified a logical target for anti-parathyroid antibodies [4]. Shortly thereafter, antibodies directed at the extracellular domain (ECD) of the CaSR were found in patients with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism [5]. Several years later, additional studies documented that some anti-CaSR antibodies can stimulate [6] or inhibit [7] the receptor, producing, respectively, hypoparathyroidism or PTH-dependent hypercalcemia. This chapter will briefly describe the CaSR's role in the homeostatic mechanisms that maintain near constancy of Ca2+o in the blood and other extracellular fluids (ECF). It will then review the history of anti-parathyroid antibodies and the subsequent elucidation of the CaSR as a target for at least some of these antibodies, including those that can directly activate or inhibit the receptor. Finally, it will discuss the treatment of the conditions associated with immunity-mediated alterations in parathyroid function.

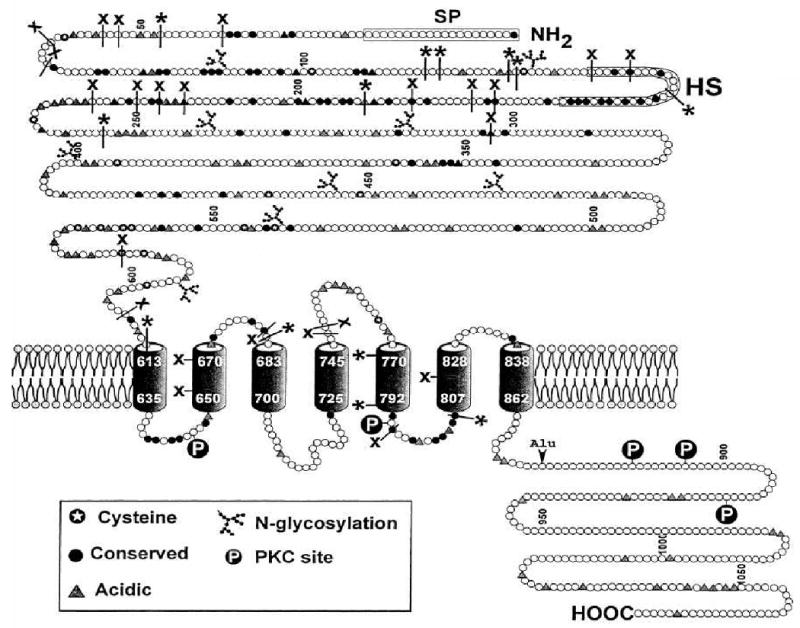

Figure 1.

Schematic view of the topology of the extracellular calcium sensing receptor, showing the amino terminal extracellular domain of the receptor in the upper part of the figure, the seven membrane-spanning domains, shown as barrel-like structures in the middle, and the intracellular C-tail at the bottom right. Also shown are cysteines, which are involved in intra- or intercellular disulfide bonds, N-glycosylation sites, acidic sites that may bind calcium ions, and regulatory protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation sites. X denote inactivating mutations, which, like inactivating antibodies, inhibit activation of the the receptor, while * indicate activating mutations, which, similar to activating antibodies, render the receptor more sensitive to extracellular calcium.

Role of the CaSR in normal mineral ion homeostasis

An understanding of the pathophysiology of hypoparathyroidism requires some knowledge of how humans maintain near constancy of Ca2+o [8,9]. The homeostatic mechanism that accomplishes this comprises three key components: (1) kidney, bone and intestine, which translocate Ca2+ into or out of the ECF in response to homeostatic signals, (2) two Ca2+o–elevating hormones, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and 1,25-dihdroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3], and a Ca2+o–lowering hormone, calcitonin (CT), which regulate the fluxes of Ca2+ into and out of the ECF; and (3) Ca2+o-sensing cells that regulate the production/secretion of these Ca2+o– regulating hormones and, in some cases, the transport of calcium ions per se. The production of the two Ca2+o–elevating hormones is normally stimulated by hypocalcemia and inhibited by hypercalcemia, while that of CT, which lowers Ca2+o by inhibiting bone resorption, is stimulated by hypercalcemia and inhibited by hypocalcemia—creating homeostatically appropriate negative feedback loops [8,9]. This system responds to a hypocalcemic challenge as follows: low Ca2+o directly stimulates the secretion of PTH by the parathyroid glands and the production of 1,25(OH)2D3 by the proximal tubular cells of the kidney [10], while at the same time inhibiting CT secretion by the thyroidal C-cells. PTH increases renal tubular Ca2+ reabsorption and enhances 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis from its precursor, 25(OH)D3. Hypocalcemia also directly increases renal tubular reabsorption of Ca2+ through the mechanism described in the next section. 1,25(OH)2D3 increases intestinal Ca2+ absorption and acts in concert with PTH to enhance net release of Ca2+ from bone. The increased fluxes of Ca2+ into the ECF from intestine and bone, coupled with renal Ca2+ conservation, restore Ca2+o toward normal, usually within a matter of minutes to hours. In addition to PTH, 1,25(OH)2D3 and CT, another recently identified protein, alpha-klotho, present in kidney and parathyroid in both membrane-bound and secreted forms, likely plays a key role in Ca2+o homeostasis by promoting PTH secretion and renal tubular Ca2+o reabsorption and inhibiting 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis [11,12].

Role of the CaSR in Ca2+o homeostasis

The molecular mechanism through which the parathyroid gland and kidney respond to changes in Ca2+o was identified in 1993 as the extracellular Ca2+–sensing receptor [4], which is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) of the same family (family 3 or C) as those sensing glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), odorants, sweet taste, and pheromones [13]. This family of receptors has large amino terminal extracellular domains (ECDs), comprising 612 amino acids in the human CaSR, and the seven membrane-spanning helices characteristic of the superfamily of GPCRs. The CaSR is heavily glycosylated and resides on the cell surface as a disulfide-linked dimer. The ECD contains important determinants for binding Ca2+o, the receptor's principal biologically relevant ligand, although there are additional Ca2+–binding sites within the 7 membrane-spanning domain, since a “headless” receptor entirely lacking the ECD still responds to Ca2+o [13]. In addition to Ca2+o, the CaSR also responds to Mg2+o, polycations (e.g., spermine and aminoglycoside antibiotics), aromatic and other amino acids, and pharmacological activators (“calcimimetics”) and antagonists (“calcilytics”) [14]. Of the naturally occurring CaSR agonists/activators, Ca2+o, Mg2+o, spermine and amino acids can be present in biological fluids at concentrations appropriate to serve as biologically relevant ligands of the receptor, although Ca2+o is by far the best characterized regulator of the CaSR. The CaSR controls cellular functions via numerous intracellular signalling pathways. It activates phospholipases A2 (PLA2) C (PLC), and D (PLD), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and inhibits adenylate cyclase [15]. These effector systems enable it to regulate numerous biological processes, including hormonal and other secretory processes, ion transporters and channels, chemotaxis, and cellular proliferation, differentiation, and death, to name a few [16].

The CaSR's best-established roles in Ca2+o homeostasis are to inhibit parathyroid cellular proliferation, PTH secretion, and PTH gene expression, to stimulate CT secretion, and to directly inhibit renal tubular Ca2+ reabsorption [17]. Less well-documented actions are promoting proliferation, chemotaxis, differentiation of osteoblasts and their mineralization of bone, as well as inhibiting osteoclastic differentiation and activity [16]. As will be seen later, some anti-CaSR antibodies exert functional effects on the CaSR, stimulating or inhibiting PTH secretion as well as CaSR-regulated second messenger pathways.

Anti-parathyroid antibodies in hypoparathyroidism

In 1966, Blizzard, et al. first reported the presence of anti-parathyroid antibodies in 38% of 75 patients with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism, 26% of 92 patients with idiopathic Addison's disease, 12% of 49 patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis and in 6% of 245 normal controls using indirect immunofluorescence [3]. Sections of parathyroid adenomas or normal human parathyroid glands were incubated with the patients' sera and then with a fluorescein-conjugated anti-human immunoglobulin antibody. The antibodies appeared to be specific for parathyroid, as it was blocked by preabsorption with parathyroid extracts but not those from gastric, thyroid, adrenal, liver or kidney tissue. Several subsequent studies raised the possibility that at least some anti-parathyroid antibodies were not, in fact, specific for parathyroid tissue but reacted with mitochondrial [18,19] or endomyseal [20] (eg., in celiac sprue) antigens. Brandi, et al., in two publications in the late 1980's further investigated the potential role of anti-parathyroid antibodies in the pathogenesis of AH. They first identified antibodies that reacted with bovine parathyroid cells and elicited complement-dependent cytotoxicity [21]. In a second study, however, these antibodies were shown to be directed predominantly at bovine parathyroid endothelial cells, raising the possibility of a novel paradigm, whereby, damage to parathyroid endothelial cells serves as the basis for parathyroid gland damage and destruction [22]. There have been no follow up investigations, however, related to these two studies.

Documentation of anti-CaSR antibodies in autoimmune hypoparathyroidism

Li, et al. [5] first identified anti-CaSR antibodies in patients with AH. They studied 25 patients with IH, 17 with APS1 and 8 with coexistent autoimmune hypothyroidism but no other endocrinopathies. By immunoblotting of human parathyroid gland extracts, sera from 5 of the 25 patients (25%) had immunoreactivity with proteins of a size consistent with the CaSR. They then utilized membrane fractions from HEK293 cells transfected with the human CaSR, which express more CaSR protein than parathyroid glands, to show that 8 sera were positive, including the five serum samples identified previously using parathyroid extracts. No reactivity was observed with membranes prepared from non-transfected HEK cells, documenting that the sera reacted with the CaSR per se. When the sera were tested for their capacity to immunoprecipitate (IP) in vitro translated CaSR ECD, 14 (56%) were positive [6 (35%) with APS1 and 8 (100%) with adult onset idiopathic hypoparathyroidism], while no anti-CaSR antibodies were detected in sera from 22 normal controls and 50 patients with other autoimmune disorders who did not have hypoparathyroidism. Those patients with AH for <5 years were more likely to harbor anti-CaSR antibodies (72%) than those with the condition for >5 years (14%), presumably because of loss of the antigen with ongoing destruction of the parathyroid glands. While the authors stated that the antibodies did not change the intracellular Ca2+ level of CaSR-transfected HEK293 cells, slow binding of antibody to the CaSR might preclude observing the transient release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores due to antibody-evoked CaSR-mediated PLC activation in this assay.

Several subsequent studies, utilizing a variety of techniques to identify anti-CaSR antibodies, have yielded generally similar results but with varying rates of positivity. Goswami, et al. [23] documented the presence of anti-CaSR antibodies in 49% of 51 patients with sporadic IH and 13.3% of healthy controls, as assessed by immunoblotting of membrane preparations of parathyroid adenomas shown to express robust CaSR levels. Six of the patients with IH had other forms of autoimmunity, including three with hypothyroidism and one with type 1 diabetes. In contrast to the results of Li, et al. [5], a study of 90 patients with APS1 failed to identify anti-CaSR antibodies utilizing immunoprecipitation of in vitro translated CaSR [24]. The basis for the difference between the results of these two studies is not known. However, the methodologies differed, and while the reactivity of a commercial anti-CaSR antiserum with its peptide antigen was used as a positive control, there were no positive controls using patient sera in the latter study. Another study [25], published the same year, investigated 17 patients with acquired IH and 14 with either APS1 or 2 for the presence of anti-CaSR antibodies using immunoblotting with in vitro translated CaSR ECD, similar to Li, et al. [5]. Five (29%) of the patients with IH and 2 (14%) of those with APS (one with APS1 and 1 with APS2) harbored anti-CaSR antibodies. A recent study by Gavalas, et al. [26] utilized three techniques, IP of CaSR expressed by CaSR-transfected HEK-293 cells, a flow cytometry assay and a radiobinding assay, to identify anti-CaSR antibodies in 14 patients with APS1 and 28 patients with Graves' disease but without AH. The first technique was most sensitive and identified anti-CaSR antibodies in 12 (86%) of the patients with APS1 and in 2 (7%) of those with Graves' disease. The variety of techniques used in these various studies to identify anti-CaSR antibodies makes it difficult to compare the results directly, and some techniques likely underestimate the prevalence of anti-CaSR antibodies. However, it appears that a substantial proportion of patients with either APS1 or adult onset IH harbor anti-CaSR antibodies. Based on the studies reviewed to this point, however, it is not possible to determine whether the antibodies played any direct role in the pathogenesis of the disorder or were simply a marker of the disease process, perhaps owing to destruction of the parathyroid glands and associated production of antibodies to self-antigen.

Hypoparathyroidism due to activating antibodies to the CaSR

Kifor, et al. reported in 2004 [6] that anti-CaSR antibodies occurring in AH could exert direct functional actions on the CaSR and, in turn, the parathyroid gland. They described two patients with IH. In one, transient hypoparathyroidism developed in a patient with Addison's disease, as manifested by hypocalcemia with an inappropriately low-normal PTH level. Over several weeks, the serum calcium and PTH levels normalized, and long-term therapy was not needed to maintain normocalcemia. In the second, a patient had coexistent hypoparathyroidism--causing seizures and requiring therapy with oral calcium and vitamin D--and difficult-to-treat Graves' disease that eventually necessitated subtotal thyroidectomy. During surgery, a parathyroid gland, normal by both size and histological criteria, was identified, demonstrating that the patient's AH had not destroyed the parathyroid glands. Both patients harbored anti-CaSR antibodies as assessed by immunoblotting of CaSR extracted from parathyroid glands or CaSR-transfected HEK cells, immunoprecipitation utilizing the patients' sera, and an ELISA using peptides from within the CaSR's ECD. In the first case, the antibody titer decreased as the hypoparathyroidism remitted. Furthermore, the anti-CaSR antibodies in both patients activated the CaSR, as documented by stimulation of PLC and MAPK in CaSR-transfected HEK293 cells and inhibition of PTH release from dispersed cells from parathyroid adenomas. Thus in both cases, the hypoparathyroidism may have resulted from a functional effect of the antibodies on the CaSR in the parathyroid glands and not from irreversible parathyroid damage [6]. In retrospect, the patient described by Possilico, et al. [27] with hypoparathyroidism that fluctuated in its severity may have harbored activating antibodies that varied in their titer. It is also worthy of note that polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies raised to the CaSR have been shown to either activate [28,29] or inhibit the receptor [7,28]. In addition, the impact of activating antibodies to the CaSR on calcium homeostasis and the functions of parathyroid and kidney is conceptually equivalent to the biochemically similar syndrome arising from activating mutations of the CaSR, autosomal dominant hypoparathyroidism or hypocalcemia (ADH) [17].

PTH-dependent hypercalcemia due to inactivating antibodies to the CaSR

In contrast to the AH due to activating antibodies to the CaSR, Kifor, et al., also described four patients, two sisters as well as a mother and her daughter, with PTH-dependent hypercalcemia, three of whom exhibited hypocalciuria [7]. The mother had coexistent celiac sprue, while her daughter and the two sisters had Hashimoto's thyroiditis. A genetic cause of PTH-dependent, hypocalciuric hypercalcemia is the autosomal dominant syndrome, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH), which results from heterozygous inactivating CaSR mutations [17]. Kifor, et al., however, ruled out FHH in these patients [7]. Their autoimmune manifestations, however, prompted a search for an autoimmune basis for their hypocalciuric hypercalcemia. All four patients, in fact, harbored inactivating CaSR antibodies that mitigated high Ca2+o-stimulated activation of PLC and MAPK and stimulated PTH secretion. This condition has been termed acquired or autoimmune hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (AHH) [30].

A subsequent report from the same group [31] described a 66 year-old hypercalcemic woman with multiple autoimmune manifestations (psoriasis, adult-onset asthma, Coomb's positive hemolytic anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, uveitis, bullous pemphigoid, sclerosing pancreatitis, and autoimmune hypophysitis with hypothyroidism and diabetes insipidus). Her hypercalcemia (as high as 13.4 mg/dl) was accompanied by elevated intact PTH levels (75-175 pg/ml) and hypocalciuria. A diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism had been made earlier, but a subtotal parathyroidectomy was followed within three weeks by recrudescence of her hypercalcemia. Remarkably, her hypercalcemia subsequently resolved during treatment with glucocorticoids for her bullous pemphigoid, and her intact PTH level decreased concomitantly to the upper limit of normal. While hypercalcemic her serum harbored anti-CaSR antibodies, but there was a substantial drop in the titer of these antibodies during glucocorticoid therapy. To date therapy with glucocorticoids has only been undertaken in this AHH patient and might be expected to be associated with long-term complications (e.g, osteoporosis and diabetes) if used chronically. As in the earlier four cases of AHH [7], the persistence of PTH-dependent hypercalcemia proves unequivocally that the anti-CaSR antibodies had not destroyed the patients' parathyroid glands. Another study [30] described a 74 year-old male patient who developed AHH and was found to harbor anti-CaSR antibodies. Interestingly, in this case the antibodies mitigated the stimulatory effect of high Ca2+o on MAPK activation in CaSR-transfected HEK293 cells, while at the same time sensitizing the HEK cells to the activation of PLC by high Ca2+o. The authors interpreted these findings as evidence that the anti-CaSR antibodies stabilized a novel conformation of the receptor that activates one heterotrimeric G protein, Gq, which is responsible for activating PLC, while at the same time reducing the coupling of the CaSR to Gi, the G protein responsible for activating MAPK in this experimental system. Such a mechanism may make it possible for physiological agonists of the CaSR and other GPCRs to couple preferentially to one or another G protein and, in turn, signalling pathway. A provocative finding, worthy of follow up, was the identification of anti-parathyroid antibodies in a very substantial proportion of patients with parathyroid adenomas [32], raising the possibility that autoimmunity to the parathyroid, and perhaps the CaSR, could participate in the pathogenesis of primary hyperparathyroidism.

Additional antigens in the parathyroid gland can also be the target of autoantibodies. Autoantibodies to NALP5 (NACHT leucine-rich-repeat protein 5), have recently been identified in 49% of patients with APS1 and hypoparathyroidism but not in any patients with APS1 without hypoparathyroidism [33], suggesting that it might be a major autoantibody in the hypoparathyroidism of APS1. NALP5 is expressed in the parathyroid in men and women as well as in the ovary in the latter. While its function is unknown, it has some of the structural characteristics of an intracellular signaling molecule.

Treatment of hypo- and hyperparathyroidism arising from AH

The usual treatment of hypoparathyroidism of any etiology is to administer active metabolites of vitamin D, such as 1,25(OH)2D3 (®Rocaltrol), on the order of 0.5-1.5 μg/day, as well as calcium supplementation of about 1-3 grams of elemental calcium in 2 to 4 divided doses [2,8], The desired therapeutic result is to maintain the serum calcium close to the lower limit of normal (8-8.5 mg/dl; 2.0-2.3 mmol/l) while at the same time avoiding the hypercalciuria (>4 mg/kg/day) that results from increased gastrointestinal absorption of calcium in the absence of the renal Ca2+ conservation normally promoted by PTH. If the desired serum calcium concentration cannot be achieved without overt hypercalciuria, treatment with a thiazide diuretic may reduce renal calcium excretion to an acceptable level. Another approach to the same problem of excessive renal calcium excretion during treatment with calcium and vitamin D is once, or preferably twice, daily subcutaneous injection of PTH(1-34), which utilizes the renal calcium-conserving action of PTH to achieve the desired level of serum calcium without excessive hypercalciuria [34].

The identification of patients with activating or inactivating antibodies to the CaSR raises the possibility of treatment with pharmacological antagonists (calcilytics) or activators (calcimimetics) of the receptor [35], respectively, in these two clinical settings. In the former case, antagonizing the antibody-mediated activation of the CaSR could stimulate PTH secretion and promote increased renal calcium excretion due to the actions of the drug in parathyroid and kidney, respectively, thereby returning serum calcium toward normal. Even in patients with AH and irreversible loss of parathyroid function, it might be possible to develop a calcilytic that would increase renal tubular reabsorption at any given level of serum calcium by antagonizing the renal CaSR, thereby facilitating maintenance of the desired level of serum calcium without hypercalciuria. Conversely, in patients with inactivating antibodies causing AHH, activation of the CaSR in parathyroid and kidney with a calcimimetic might reverse or ameliorate the PTH-dependent hypercalcemia and hypocalciuria.

Acknowledgments

The author was supported by NIH grants, DK67111 and DK67155.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The author has a financial interest in the calcimimetic, ®cinacalcet HCl (®sensipar).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Betterle C. Parathyroid and autoimmunity. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2006;67:147–54. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4266(06)72571-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whyte MP. Autoimmune Hypoparathyroidism. In: Bilezikian JP, Marcus R, Levine MA, editors. The Parathyroids. Second. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 791–805. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blizzard RM, Chee D, Davis W. The incidence of parathyroid and other antibodies in the sera of patients with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. Clin Exp Immunol. 1966;1:119–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown EM, Gamba G, Riccardi D, et al. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature. 1993;366:575–80. doi: 10.1038/366575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Song YH, Rais N, et al. Autoantibodies to the extracellular domain of the calcium sensing receptor in patients with acquired hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:910–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI118513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kifor O, McElduff A, LeBoff MS, et al. Activating antibodies to the calcium-sensing receptor in two patients with autoimmune hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:548–56. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kifor O, Moore FD, Jr, Delaney M, et al. A syndrome of hypocalciuric hypercalcemia caused by autoantibodies directed at the calcium-sensing receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:60–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bringhurst FR, Demay MB, Kronenberg HM. Hormones and disorders of mineral metabolism. In: Wilson JD, Foster DW, Kronenberg HM, et al., editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 9. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1998. pp. 1155–209. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown EM. Physiology of Calcium homeostasis. In: Biliezikian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan G, editors. The Parathyroids. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 167–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisinger JR, Favus MJ, Langman CB, et al. Regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by calcium in the parathyroidectomized, parathyroid hormone-replete rat. J Bone Miner Res. 1989;4:929–35. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nabeshima YI, Imura H. alpha-Klotho: A Regulator That Integrates Calcium Homeostasis. Am J Nephrol. 2007;28:455–64. doi: 10.1159/000112824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renkema KY, Alexander RT, Bindels RJ, et al. Calcium and phosphate homeostasis: Concerted interplay of new regulators. Ann Med. 2008;40:82–91. doi: 10.1080/07853890701689645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brauner-Osborne H, Wellendorph P, Jensen AA. Structure, pharmacology and therapeutic prospects of family C G-protein coupled receptors. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:169–84. doi: 10.2174/138945007779315614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conigrave AD, Quinn SJ, Brown EM. Cooperative multi-modal sensing and therapeutic implications of the extracellular Ca(2+) sensing receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:401–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01546-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward DT. Calcium receptor-mediated intracellular signalling. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:217–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown EM, MacLeod RJ. Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:239–97. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauache OM. Extracellular calcium-sensing receptor: structural and functional features and association with diseases. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:577–84. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swana GT, Swana MR, Bottazzo GF, et al. A human-specific mitochondrial antibody its importance in the identification of organ-specific reactions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;28:517–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betterle C, Caretto A, Zeviani M, et al. Demonstration and characterization of anti-human mitochondria autoantibodies in idiopathic hypoparathyroidism and in other conditions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;62:353–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar V, Valeski JE, Wortsman J. Celiac disease and hypoparathyroidism: cross-reaction of endomysial antibodies with parathyroid tissue. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:143–6. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.2.143-146.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandi ML, Aurbach GD, Fattorossi A, et al. Antibodies cytotoxic to bovine parathyroid cells in autoimmune hypoparathyroidism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:8366–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fattorossi A, Aurbach GD, Sakaguchi K, et al. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies: detection and characterization in sera from patients with autoimmune hypoparathyroidism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4015–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goswami R, Brown EM, Kochupillai N, et al. Prevalence of calcium sensing receptor autoantibodies in patients with sporadic idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:9–18. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soderbergh A, Myhre AG, Ekwall O, et al. Prevalence and clinical associations of 10 defined autoantibodies in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:557–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer A, Ploix C, Orgiazzi J, et al. Calcium-sensing receptor autoantibodies are relevant markers of acquired hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4484–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavalas NG, Kemp EH, Krohn KJ, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor is a target of autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2107–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Posillico JT, Wortsman J, Srikanta S, et al. Parathyroid cell surface autoantibodies that inhibit parathyroid hormone secretion from dispersed human parathyroid cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1986;1:475–83. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650010512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu J, Reyes-Cruz G, Goldsmith PK, et al. Functional effects of monoclonal antibodies to the purified amino-terminal extracellular domain of the human Ca(2+) receptor. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:601–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roussanne MC, Gogusev J, Hory B, et al. Persistence of Ca2+-sensing receptor expression in functionally active, long-term human parathyroid cell cultures. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:354–62. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makita N, Sato J, Manaka K, et al. An acquired hypocalciuric hypercalcemia autoantibody induces allosteric transition among active human Ca-sensing receptor conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5443–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701290104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pallais JC, Kifor O, Chen YB, et al. Acquired hypocalciuric hypercalcemia due to autoantibodies against the calcium-sensing receptor. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:362–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjerneroth G, Juhlin C, Gudmundsson S, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class II expression and parathyroid autoantibodies in primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 1998;124:503–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alimohammadi M, Bjorklund P, Hallgren A, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 and NALP5, a parathyroid autoantigen. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winer KK, Ko CW, Reynolds JC, et al. Long-term treatment of hypoparathyroidism: a randomized controlled study comparing parathyroid hormone-(1-34) versus calcitriol and calcium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4214–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nemeth EF. Calcimimetic and calcilytic drugs: just for parathyroid cells? Cell Calcium. 2004;35:283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]