Abstract

The plasma membrane is organized into various subdomains of clustered macromolecules. Such domains include adhesive structures (cellular synapses, substrate adhesions, and cell–cell junctions) and membrane invaginations (clathrin-coated pits and caveolae), as well as less well-defined domains such as lipid rafts and lectin-glycoprotein lattices. Domains are organized by specialized scaffold proteins including the intramembranous caveolins, which stabilize lipid raft domains, and the galectins, a family of animal lectins that cross-link glycoproteins forming molecular lattices. We review evidence that these heterogeneous microdomains interact to regulate substratum adhesion and cytokine receptor dynamics at the cell surface.

Introduction

Cellular compartmentalization into and within organelles segregates biochemical reactions and increases local molecular concentrations, thereby promoting efficiency of cellular processes. At the plasma membrane, subdomains generate lateral heterogeneity that organizes the spatial distribution of glycoprotein receptors and membrane-proximal effectors. Morphologically identifiable plasma membrane domains include the neuronal and immunological synapses, clathrin-coated pits, caveolae, focal adhesions, and cell–cell junctions. Lipid rafts, including Cav1 oligomers or scaffolds, and galectin-glycoprotein lattices form classes of plasma membrane domains that are poorly defined morphologically. Lipid rafts are transient, nanoscale domains enriched for cholesterol and sphingolipids. Cav1 scaffolds are stabilized mesoscale (5–100 nm) raft domains, which likely contain at least 15 Cav1 molecules. Galectins bind and cross-link N-glycans on cell surface glycoproteins to form a heterogeneous lattice. The scaffolding function of caveolins and galectins promotes recruitment of proteins and lipids to domains where homotypic and heterotypic clustering modulates the dynamics and functionality of plasma membrane molecules. Macromolecular complexes often exhibit restricted diffusion in membranes of living cells due to their reduced ability to cross barriers between membrane compartments (Kusumi et al., 2005). Domain formation and dynamics are therefore tightly regulated by various cellular components including the actin cytoskeleton and scaffold proteins. In this mini-review, we describe how concerted and competitive interactions between rafts, scaffolds, and lattices regulate receptor dynamics and add another layer of complexity to receptor signaling at the cell surface.

Lattices

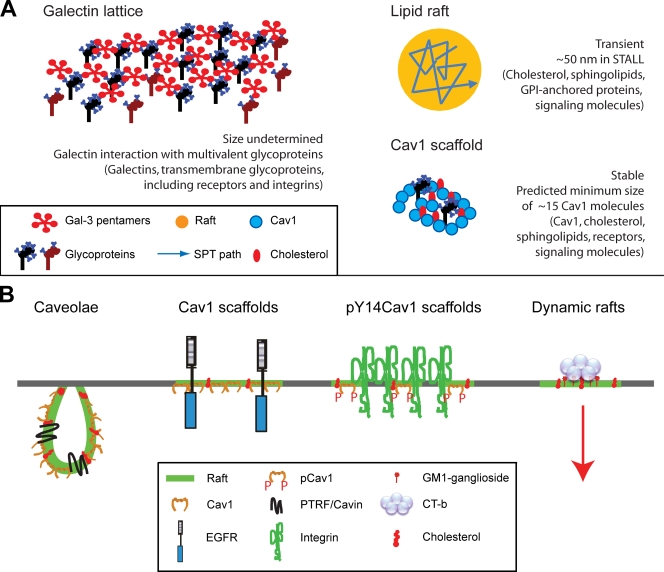

Galectins are a family of lectins that bind Gal-GlcNAc branches of N-glycans of glycoproteins. Interaction of dimeric and pentameric galectins (Fig. 1) with multivalent cell surface glycoproteins promotes lattice formation (Demetriou et al., 2001; Ahmad et al., 2004; Partridge et al., 2004). Branched N-glycans, particularly tetraantennary structures generated by Golgi β1, 6N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V (GlcNAc-TV; encoded by the Mgat5 gene), represent higher affinity ligands for galectins (Hirabayashi et al., 2002). The number of N-glycans present on glycoproteins also controls galectin affinity for glycosylated receptors (Lau et al., 2007). When added to the surface of neutrophils and endothelial cells, fluorescently conjugated galectin-3 (Gal-3) forms stable oligomers (Nieminen et al., 2007). Gal-3 binding also regulates diffusion rates of cell surface glycoprotein receptors and integrins (Lajoie et al., 2007; Goetz et al., 2008a). Lattices are therefore domains that function to promote homotypic and heterotypic interactions. However, the dynamics and composition of galectin lattices in different cell types remain to be determined.

Figure 1.

Plasma membrane domains. (A) Depictions of lattices as multivalent interactions between pentameric Gal-3 and glycoproteins, rafts as a component of STALL by single particle tracking (Suzuki et al., 2007b), and scaffolds as a minimum oligomer of 15 Cav1 molecules. Illustrations are not drawn to scale. (B) Cav1 domains include caveolae, Cav1 scaffolds, and pY14Cav1 scaffold domains in focal adhesions. Cav1 scaffolds may function to restrict signaling of cytokine receptors, such as EGFR, through direct interactions. However, how stable Cav1 domains regulate dynamic raft behavior, both within the plane of the membrane and in the endocytosis of various ligands such as CT-b, remains unclear.

One potential role for the lattice might be to enhance crosstalk between integrins and signaling receptors. Indeed, Mgat5 expression regulates EGF-dependent dephosphorylation of FAK and activation of Shp2, key regulators of focal adhesion dynamics (Guo et al., 2007). Integrin cross-linking by Gal-1 recruits pre-B cell receptors into the immune synapse (Rossi et al., 2006). Further N-glycan modifications can fine tune galectin binding. For instance, terminal α2-6 sialylation of N-glycans on integrins and the TRPV5 Ca2+ channel reduces binding to galectins (Cha et al., 2008; Zhuo et al., 2008), and may represent a general regulator of lattice avidity.

Rafts

Lipid rafts are dynamic cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich membrane domains. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer, single particle tracking, and electron microscopy studies all support the concept of rafts as dynamic and transient nanoscale structures (Hancock, 2006). Lipid rafts may however fuse in response to signaling events into larger, more stable signal transduction platforms (Simons and Toomre, 2000).

Advances in temporal and spatial resolution using single particle tracking and stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy have highlighted the cholesterol-sensitive, subsecond (10–20 ms in <20-nm domains by STED) transient anchoring of raft-associated sphingolipids and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins (Chen et al., 2006; Eggeling et al., 2009). The GPI-anchored CD59 receptor interacts frequently with its effector, Lyn kinase; but only after recruitment of Gαι2 does the CD59–Lyn complex stabilize, forming a domain (∼50 nm in diameter) termed “stimulation-induced temporary arrest of lateral diffusion” (STALL). STALL is actin-dependent and cholesterol-sensitive, and replacing the GPI anchor of Lyn with a nonraft transmembrane domain limits STALL, implicating rafts in STALL formation (Fig. 1 A; Suzuki et al., 2007a,b). Cortical actin is also a critical determinant of the formation of cholesterol-sensitive GPI-anchored protein nanoclusters (Goswami et al., 2008). Transient recruitment and stabilization of signaling complexes within rafts thereby generates quantal signals whose integration produces the bulk cellular signaling response.

Scaffolds and noncaveolar Cav1

Oligomerized Cav1 microdomains, for which we propose the name “Cav1 scaffold,” represent stable raft structures that may exhibit many of the signaling regulatory properties associated with Cav1. Cav1 is the major protein constituent of caveolae, smooth cholesterol-sensitive invaginations of the plasma membrane (Parton and Simons, 2007) whose formation also requires a cytoplasmic protein, PTRF-Cavin (Hill et al., 2008; Liu and Pilch, 2008). Caveolae are predicted to contain between 100 and 200 Cav1 molecules, but the minimal SDS-stable Cav1 oligomer contains only ∼15 Cav1 molecules (Monier et al., 1995; Parton et al., 2006) that may correspond to the Cav1 scaffold domain (Fig. 1). Indeed, even when expressed at low levels independently of caveolae formation, Cav1 still forms oligomers that are effectively immobile in the plasma membrane (Lajoie et al., 2007). As discussed below, noncaveolar functions of the Cav1 scaffold may include regulation of growth factor receptor signaling, raft-dependent endocytosis, and focal adhesion dynamics.

Cav1 is a well-characterized inhibitor of growth factor receptor signaling (Goetz et al., 2008b). For example, Cav1 interacts with EGF receptor (EGFR) via its 20–amino acid scaffolding domain and negatively regulates EGF responsiveness and EGFR lateral diffusion, even under conditions of reduced caveolae formation (Couet et al., 1997; Lajoie et al., 2007). Furthermore, EGFR distribution to morphologically defined caveolae by electron microscopy is evident only in cells treated with high levels of EGF (Sigismund et al., 2005). This suggests that in the absence of ligand, EGFR binds Cav1 outside of caveolae. Similarly, endothelial cell-specific expression of Cav1 reduces endothelial NOS activation but not plasma membrane caveolae, which suggests a functional role for noncaveolar Cav1 (Bauer et al., 2005).

Cav1 may function indirectly to regulate raft-dependent endocytosis by altering the lipid composition of raft domains (Lajoie and Nabi, 2007). Cav1 inhibition of the raft-dependent endocytosis of cholera toxin b subunit (CT-b) and dysferlin occurs independently of direct interaction with Cav1 or caveolae (Hernandez-Deviez et al., 2008; Lajoie et al., 2009). Overexpression of glycosphingolipids and cholesterol overrides negative regulation of raft-dependent endocytosis by Cav1 (Sharma et al., 2004). Cav1 binding to cholesterol and recruitment of cholesterol to raft domains (Murata et al., 1995; Smart et al., 1996) could induce both local and global changes in membrane lipid composition that impact on the dynamics, functionality, and endocytic potential of lipid rafts.

Cav1 is a substrate of Src kinase, and its tyrosine 14 phosphorylation (pY14Cav1) regulates its interaction with integrins, various signaling adapters, and protein tyrosine phosphatases (Goetz et al., 2008b). The ability of pY14Cav1 to induce ordered microdomains within focal adhesions as well as stabilize focal adhesion–associated FAK implicates pY14Cav1-mediated domain organization in the promotion of focal adhesion signaling and turnover leading to increased tumor cell migration (Gaus et al., 2006; Goetz et al., 2008a; Joshi et al, 2008). Structural differences between oligomerized Cav1 and pY14Cav1 scaffold domains remain unclear; however, both appear to regulate the formation of ordered lipid domains (Gaus et al., 2006; Parton and Simons, 2007). Collectively, stable Cav1 oligomers distinct from caveolae therefore form scaffolds that interact with proteins and lipids to regulate plasma membrane organization, cell surface signaling, and raft-dependent endocytosis (Fig. 1 B).

Domain interplay at the cell surface

Exchange of receptors between membrane domains is a critical aspect of cellular sensitivity to extracellular cues. Reduced T cell activation and autoimmunity in mice lacking Mgat5 and the galectin lattice is due to enhanced T cell receptor (TCR) clustering (Demetriou et al., 2001). In resting T cells, the Mgat5/galectin lattice partitions CD45 inside the raft immune synapse and partitions TCR–CD4-Lck–Zap-70 complexes outside the raft immune synapse, opposing cytoplasmic interactions with the actin cytoskeleton and TCR activation (Chen et al., 2007). Recruitment to the galectin lattice, promoted by metabolite flux through the hexosamine pathway (Grigorian et al., 2007), dampens TCR signaling and autoimmunity by sequestering TCR outside the immune synapse.

For EGFR and other cytokine receptors (including TGFβR, PDGFR, and insulin-like growth factor receptor [IGFR]), receptor recruitment to the galectin lattice potentiates ligand-induced clustering and signaling (Partridge et al., 2004). In mammary tumor cells, the Mgat5/galectin lattice sequesters EGFR, protecting them from interacting with Cav1 scaffolds, hence promoting growth factor signaling potential and tumor growth (Lajoie et al., 2007). Multivalent association of EGFR with the galectin lattice under conditions of higher N-glycan branching (i.e., Mgat5 activity) appears to be dominant over stable interaction of the receptor with Cav1 scaffolds.

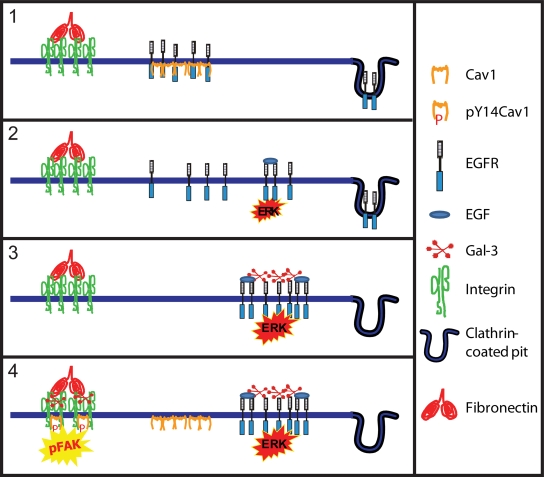

pY14Cav1 promotion of FAK stabilization in focal adhesions is dependent on expression of Mgat5 and Gal-3 (Goetz et al., 2008a). In light of the ability of pY14Cav1 to induce raft-like domains within focal adhesions (Gaus et al., 2006), this is a clear example of microdomain interaction where the extracellular galectin lattice works in concert with intracellular pY14Cav1 scaffold domains to regulate focal adhesion dynamics and cell motility. The ability of the lattice to relieve EGFR suppression, to override Cav1 tumor suppressor activity, and to function with pY14Cav1 to promote tumor cell migration provides an elegant example of how membrane domains interact to regulate complex cell behavior (Fig. 2). The galectin lattice and raft domains therefore compete to regulate receptor signaling, with the lattice functioning as both a suppressor (TCR) and enhancer (EGFR, others) of receptor availability to the ligand, but they also synergize to promote integrin-dependent focal adhesion dynamics.

Figure 2.

Cav1 and Gal-3 in tumor progression. (1) In cells lacking the galectin lattice, Cav1 scaffolds recruit receptors and inhibit signaling. (2) Loss of Cav1 enables receptor signaling, promoting tumor cell proliferation and tumor growth. (3) Expression of Mgat5-branched N-glycans and Gal-3 and receptor recruitment to the galectin lattice limits receptor down-regulation via endocytosis, and promotes signaling potential. (4) Receptor sequestration by the galectin lattice overrides Cav1 suppressor activity, enabling elevated Cav1 expression in advanced tumors. Gal-3 and pY14Cav1 work together to promote focal adhesion turnover and enhance FAK activation, tumor cell migration, and metastasis. Competitive and coordinate action between Cav1 scaffolds and the galectin lattice at various stages of tumor progression may explain how Cav1 can act as both a tumor promoter and suppressor.

Conclusion

At the plasma membrane, caveolins and galectins play important roles as molecular organizers that promote heterotypic protein and lipid interactions to modulate molecular diffusion and turnover of functional domains. The lattice and Cav1 scaffold domains regulate recruitment, dynamics, and exchange of glycoproteins and lipids between membrane microdomains. Crosstalk between lattices, scaffolds, and rafts represents an exciting new level of plasma membrane complexity that is likely to provide insight into the cell biology of development and disease.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP-43938.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; STALL, stimulation-induced temporary arrest of lateral diffusion; TCR, T cell receptor.

References

- Ahmad N., Gabius H.J., Andre S., Kaltner H., Sabesan S., Roy R., Liu B., Macaluso F., Brewer C.F. 2004. Galectin-3 precipitates as a pentamer with synthetic multivalent carbohydrates and forms heterogeneous cross-linked complexes.J. Biol. Chem. 279:10841–10847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer P.M., Yu J., Chen Y., Hickey R., Bernatchez P.N., Looft-Wilson R., Huang Y., Giordano F., Stan R.V., Sessa W.C. 2005. Endothelial-specific expression of caveolin-1 impairs microvascular permeability and angiogenesis.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:204–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha S.K., Ortega B., Kurosu H., Rosenblatt K.P., Kuro O.M., Huang C.L. 2008. Removal of sialic acid involving Klotho causes cell-surface retention of TRPV5 channel via binding to galectin-1.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:9805–9810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I.J., Chen H.L., Demetriou M. 2007. Lateral compartmentalization of T cell receptor versus CD45 by galectin-N-glycan binding and microfilaments coordinate basal and activation signaling.J. Biol. Chem. 282:35361–35372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Thelin W.R., Yang B., Milgram S.L., Jacobson K. 2006. Transient anchorage of cross-linked glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins depends on cholesterol, Src family kinases, caveolin, and phosphoinositides.J. Cell Biol. 175:169–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couet J., Sargiacomo M., Lisanti M.P. 1997. Interaction of a receptor tyrosine kinase, EGF-R, with caveolins. Caveolin binding negatively regulates tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase activities.J. Biol. Chem. 272:30429–30438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou M., Granovsky M., Quaggin S., Dennis J.W. 2001. Negative regulation of T-cell activation and autoimmunity by Mgat5 N-glycosylation.Nature. 409:733–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggeling C., Ringemann C., Medda R., Schwarzmann G., Sandhoff K., Polyakova S., Belov V.N., Hein B., von Middendorff C., Schonle A., Hell S.W. 2009. Direct observation of the nanoscale dynamics of membrane lipids in a living cell.Nature. 457:1159–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaus K., Le Lay S., Balasubramanian N., Schwartz M.A. 2006. Integrin-mediated adhesion regulates membrane order.J. Cell Biol. 174:725–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz J.G., Joshi B., Lajoie P., Strugnell S., Scudamore T., Kojic L., Nabi I.R. 2008a. Concerted regulation of focal adhesion dynamics by galectin-3 and tyrosine phosphorylated caveolin-1.J. Cell Biol. 180:1261–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz J.G., Lajoie P., Wiseman S.M., Nabi I.R. 2008b. Caveolin-1 in tumor progression: the good, the bad and the ugly.Cancer Metastasis Rev. 27:715–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami D., Gowrishankar K., Bilgrami S., Ghosh S., Raghupathy R., Chadda R., Vishwakarma R., Rao M., Mayor S. 2008. Nanoclusters of GPI-anchored proteins are formed by cortical actin-driven activity.Cell. 135:1085–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorian A., Lee S.U., Tian W., Chen I.J., Gao G., Mendelsohn R., Dennis J.W., Demetriou M. 2007. Control of T cell-mediated autoimmunity by metabolite flux to N-glycan biosynthesis.J. Biol. Chem. 282:20027–20035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.-B., Randolph M., Pierce M. 2007. Inhibition of a specific N-glycosylation activity results in attenuation of breast carcinoma cell invasiveness-related phenotypes: inhibition of epidermal growth factor-induced dephosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase.J. Biol. Chem. 282:22150–22162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J.F. 2006. Lipid rafts: contentious only from simplistic standpoints.Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:456–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Deviez D.J., Howes M.T., Laval S.H., Bushby K., Hancock J.F., Parton R.G. 2008. Caveolin regulates endocytosis of the muscle repair protein, dysferlin.J. Biol. Chem. 283:6476–6488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M.M., Bastiani M., Luetterforst R., Kirkham M., Kirkham A., Nixon S.J., Walser P., Abankwa D., Oorschot V.M., Martin S., et al. 2008. PTRF-Cavin, a conserved cytoplasmic protein required for caveola formation and function.Cell. 132:113–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi J., Hashidate T., Arata Y., Nishi N., Nakamura T., Hirashima M., Urashima T., Oka T., Futai M., Muller W.E., et al. 2002. Oligosaccharide specificity of galectins: a search by frontal affinity chromatography.Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1572:232–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi B., Strugnell S.S., Goetz J.D., Kojic L.D., Cox M.E., Griffith O.L., Chan S.K., Jones S.J., Leung S.P., Masoudi H., Leung S., Wiseman S.M., Nabi I.R. 2008. Phosphorylated caveolin-1 regulates Rho/ROCK-dependent focal adhesion dynamics and tumor cell migration and invasion.Cancer Res. 68:8210–8220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumi A., Nakada C., Ritchie K., Murase K., Suzuki K., Murakoshi H., Kasai R.S., Kondo J., Fujiwara T. 2005. Paradigm shift of the plasma membrane concept from the two-dimensional continuum fluid to the partitioned fluid: high-speed single-molecule tracking of membrane molecules.Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34:351–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie P., Nabi I.R. 2007. Regulation of raft-dependent endocytosis.J. Cell. Mol. Med. 11:644–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie P., Partridge E., Guay G., Goetz J.G., Pawling J., Lagana A., Joshi B., Dennis J.W., Nabi I.R. 2007. Plasma membrane domain organization regulates EGFR signaling in tumor cells.J. Cell Biol. 179:341–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie P., Kojic L., Nim S., Li L., Dennis J., Nabi I.R. 2009. Caveolin-1 regulates the dynamin-dependent raft-mediated endocytosis of cholera toxin b independently of caveolae.J. Cell. Mol. Med. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K.S., Partridge E.A., Grigorian A., Silvescu C.I., Reinhold V.N., Demetriou M., Dennis J.W. 2007. Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation.Cell. 129:123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Pilch P.F. 2008. A critical role of cavin (polymerase I and transcript release factor) in caveolae formation and organization.J. Biol. Chem. 283:4314–4322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monier S., Parton R.G., Vogel F., Behlke J., Henske A., Kurzchalia T.V. 1995. VIP21-caveolin, a membrane protein constituent of the caveolar coat, oligomerizes in vivo and in vitro.Mol. Biol. Cell. 6:911–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata M., Peranen J., Schreiner R., Wieland F., Kurzchalia T.V., Simons K. 1995. VIP21/caveolin is a cholesterol-binding protein.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:10339–10343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen J., Kuno A., Hirabayashi J., Sato S. 2007. Visualization of galectin-3 oligomerization on the surface of neutrophils and endothelial cells using fluorescence resonance energy transfer.J. Biol. Chem. 282:1374–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton R.G., Simons K. 2007. The multiple faces of caveolae.Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton R.G., Hanzal-Bayer M., Hancock J.F. 2006. Biogenesis of caveolae: a structural model for caveolin-induced domain formation.J. Cell Sci. 119:787–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge E.A., Le Roy C., Di Guglielmo G.M., Pawling J., Cheung P., Granovsky M., Nabi I.R., Wrana J.L., Dennis J.W. 2004. Regulation of cytokine receptors by Golgi N-glycan processing and endocytosis.Science. 306:120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi B., Espeli M., Schiff C., Gauthier L. 2006. Clustering of pre-B cell integrins induces galectin-1-dependent pre-B cell receptor relocalization and activation.J. Immunol. 177:796–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D.K., Brown J.C., Choudhury A., Peterson T.E., Holicky E., Marks D.L., Simari R., Parton R.G., Pagano R.E. 2004. Selective stimulation of caveolar endocytosis by glycosphingolipids and cholesterol.Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:3114–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigismund S., Woelk T., Puri C., Maspero E., Tacchetti C., Transidico P., Di Fiore P.P., Polo S. 2005. Clathrin-independent endocytosis of ubiquitinated cargos.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:2760–2765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K., Toomre D. 2000. Lipid rafts and signal transduction.Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart E.J., Ying Y., Donzell W.C., Anderson R.G. 1996. A role for caveolin in transport of cholesterol from endoplasmic reticulum to plasma membrane.J. Biol. Chem. 271:29427–29435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K.G., Fujiwara T.K., Edidin M., Kusumi A. 2007a. Dynamic recruitment of phospholipase C γ at transiently immobilized GPI-anchored receptor clusters induces IP3-Ca2+ signaling: single-molecule tracking study 2.J. Cell Biol. 177:731–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K.G., Fujiwara T.K., Sanematsu F., Iino R., Edidin M., Kusumi A. 2007b. GPI-anchored receptor clusters transiently recruit Lyn and G α for temporary cluster immobilization and Lyn activation: single-molecule tracking study 1.J. Cell Biol. 177:717–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo Y., Chammas R., Bellis S.L. 2008. Sialylation of beta1 integrins blocks cell adhesion to galectin-3 and protects cells against galectin-3-induced apoptosis.J. Biol. Chem. 283:22177–22185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]