Abstract

Background

The specific associations between plant roots and the soil microbial community are key to understanding nutrient cycling in grasslands, but grass roots can be difficult to identify using morphology alone. A molecular technique to identify plant species from root DNA would greatly facilitate investigations of the root rhizosphere.

Results

We show that trnL PCR product length heterogeneity and a maximum of two restriction digests can separate 14 common grassland species. The RFLP key was used to identify root fragments at least to genus level in a field study of upland grassland community diversity. Roots which could not be matched to known types were putatively identified by comparison of the nuclear ribosomal ITS sequence to the GenBank database. Ten taxa were identified among almost 600 root fragments. Additionally, we have employed capillary electrophoresis of fluorescent trnL PCR products (fluorescent fragment length polymorphism, FFLP) to discriminate all taxa identified at the field site.

Conclusion

We have developed a molecular database for the identification of some common grassland species based on PCR-RFLP of the plastid transfer RNA leucine (trnL) UAA gene intron. This technique will allow fine-scale studies of the rhizosphere, where root identification by morphology is unrealistic and high throughput is desirable.

Background

Plants can be difficult to identify from roots, even for experienced taxonomists. Fine roots often grow deep and intertwined with each other in swards and it is not easy to link above and below ground plant parts for morphological identification. Studies of of below-ground processes are currently hindered by the inability to identify fine roots in soil [1]. To understand nutrient cycling in an upland grassland we are studying the spatial relationship between co-occurring plant roots and their associated microbes, both endomycorrhizal fungi and rhizoplane bacteria. To address the question 'do the roots of different plant species harbour distinct microbial populations?' we first required a method to identify plant species from root fragments.

A molecular method for identification must satisfy requirements for specific amplification of plant DNA and reveal enough variability to distinguish species. The trnL UAA intron from plastid DNA shows variability comparable to that of nuclear intergenic regions and can resolve taxa at the genus/species level in RFLP-based studies[2]. It has been exploited to identify tree species from fine roots collected in the Alps [3]. Sequence variation in the trnL intron has also been used to identify Cinnamomum species [4] and cyanobacterial partners of Peltigera lichens [5], and has recently been used to confirm morphological identification of three grass species in a study of AM diversity in upland grassland [6].

Our aims were firstly to extend the molecular data for grasses so that we could identify, to species level, small (< 1 cm) root fragments collected from soil cores sampled from an upland grassland, and secondly, to develop a high-throughput method of plant root identification utilising capillary electrophoresis of fluorescently labelled PCR products.

Results and Discussion

trnL PCR-RFLP key to grass identification

The trnL intron was successfully amplified from a range of grasses including the dominant species recorded at the field site. Nucleotide sequence data was deposited in GenBank with accession numbers as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key to grass identification at Sourhope using trnL PCR-RFLP. Fragment sizes were determined using nucleotide sequence data of the trnL PCR product of each reference species. Restriction enzyme(s) are followed by the fragment sizes expected from digestion with the enzyme(s). GenBank accession numbers are provided in brackets following the species name.

| trnL PCR | Restriction digest 1 | Restriction digest 2 | Identity (accession number) |

| ~500 bp | BfaI: 158/277/61 | Agrostis capillaris (AY177347b) | |

| BfaI: 439/61 | Agrostis vinealis (AY177332) | ||

| >500 bp | NlaIV/DdeI: 57/53/187/317-329 | Poa pratensis/trivialisa(AY177349b/AY177338) | |

| NlaIV/DdeI: 57/53/200-204/298-300 | XmnI: 197/45/367-370 | Festuca rubra/ovinaa (AY177345b/AY177342) | |

| XmnI: 197/45/178/154 | Festuca juncifolia (AY177344) | ||

| NlaIV/DdeI: 57/53/505-536 | Hsp92II: 125/435/86 | Deschampsia flexuosa (AY177336) | |

| Hsp92II: 125/405/86 | Deschampsia caespitosa (AY177335) | ||

| Hsp92II: 336/200/86 | Nardus stricta (AY177337) | ||

| Hsp92II: 563/86 | Holcus lanatus (AY177348) | ||

| Hsp92II: 343/281 | Luzula campestris (AY177333) | ||

| Hsp92II: 528/86 | Phleum pratense (AY177339) |

a can be separated by ITS PCR-RFLP with HinfI (Pp:335/293/76/17, Pt:293/207/127/76/17; Fr:337/297/76/17, Fo:293/230/107/76/17) b sequences from reference [6].

Using sequence data, we selected restriction digests which would separate the taxa. PCR products varied in size from 496 bp – 646 bp, and this length heterogeneity provided a useful character for discriminating Agrostis spp. from other grasses (Table 1). Agrostis was subdivided into A. capillaris and A. vinealis with BfaI. A double digest with NlaIV and DdeI allowed the remaining species to be separated into Festuca, Poa and 'others'. The Festuca group was further divided to F. arundinaceae, F. juncifolia and F. rubra/F. ovina with XmnI. F. rubra and F. ovina proved difficult to separate by trnL RFLP since they varied at only 6 nucleotide positions. P. pratensis and P. trivialis were also not separable by RFLP since the trnL intron sequences did not contain informative restriction site differences. The trnL intron of closely related species may not always contain enough sequence variation for separation by RFLP [3]. However, we were able to distinguish between F. rubra & F. ovina, and between P. pratensis & P. trivialis by amplification of the ribosomal ITS region followed by digestion with HinfI. Amplification with ITS4 and the newly designed ITS1P consistently amplified a single band from reference plant DNA but often produced multiple bands from environmental samples. However, optimisation of cycling conditions allowed the amplification of a single band from environmental root samples.

The remaining sequences, Deschampsia caespitosa, Deschampsia flexuosa, Nardus stricta, Holcus lanatus, Luzula campestris and Phleum pratense, were separated by digestion with Hsp92II. With a combination of length heterogeneity and one or two enzyme digests a total of ten taxa could be identified to species and the remaining four to genus level. A key was designed to aid interpretation of trnL PCR product length and restriction patterns (Table 1).

Identification of field roots

The RFLP key was used in an attempt to identify 960 root fragments sampled from the field. Amplification yielded a single PCR product in 579 roots (60.3 %), and a mixed product in 17 roots (1.8 %), possibly due to small root fragments of more than one species. Samples which twice failed to amplify were considered either to be dead and degraded, or to contain inhibitory compounds co-precipitated from root pigments or adhering soil. Co-precipitation of root pigments has previously been reported to inhibit PCR [7] and we made no attempt to remove soil particles since the molecular characterisation of rhizoplane microbes was the subject of a related study.

By comparing RFLP patterns to the key we were able to assign most root fragments to species. Ten grass species were represented among the 579 root fragments analysed. The frequency and distribution of each species across the study site was determined. Agrostis capillaris dominated the root population, representing 61.3 % of identified roots (Table 2) and present in every core. Eleven percent of roots were identified as A. vinealis, 7.8 % D. caespitosa, 7.3 % F. rubra and 5.4 % P. pratensis. The remaining species occurred at frequencies of less than 5 % (Table 2). Using this method we were able to select a subset of samples for further analysis of microbial diversity such that comparative information could be maximised within and between species and cores (results not shown).

Table 2.

Occurrence of grass species at Sourhope based on identification of 579 roots.

| Taxon | Number of roots | Frequency of occurrence (%) | Number sequenced |

| Agrostis capillaris | 355 | 61.3 | 11 |

| Agrostis vinealis | 66 | 11.4 | 2 |

| Deschampsia caespitosa | 45 | 7.8 | 4 |

| Festuca rubra | 42 | 7.3 | 6 |

| Poa pratensis | 31 | 5.4 | 3 |

| Agrostis sp. | 19 | 3.3 | 4 |

| Festuca sp. | 14 | 2.4 | 2 |

| Nardus stricta | 3 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Holcus sp. | 3 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 1 | 0.2 | 1 |

While the majority of RFLP patterns matched the grass species known to be present at the site, a few roots yielded unexpected patterns. Fourteen roots yielded an RFLP pattern which matched F. juncifolia and three roots matched H. lanatus. Since these species have not been recorded at the Sourhope field site or indeed at this altitude, corresponding roots were cautiously recorded as Festuca sp. and Holcus sp.

Using ITS-RFLP to distinguish F. rubra from F. ovina and P. pratensis from P. trivialis, only the F. rubra and P. pratensis types were detected. Nineteen root samples displayed an RFLP pattern not seen in any of our 'key' species. A Blast search [8] of the NCBI database using the ITS sequence from of a subset of the unassigned samples matched Calamagrostis epigeios most closely although this species has not been detected in previous vegetation surveys of the site. The number of ITS sequences in Genbank makes this region potentially more useful than the trnL intron for identifying unknowns but because the chloroplast trnL intron is plant-specific we thought it better suited to plant identification than the nuclear-encoded ITS which can sometimes be amplified from both plants and fungi [9].

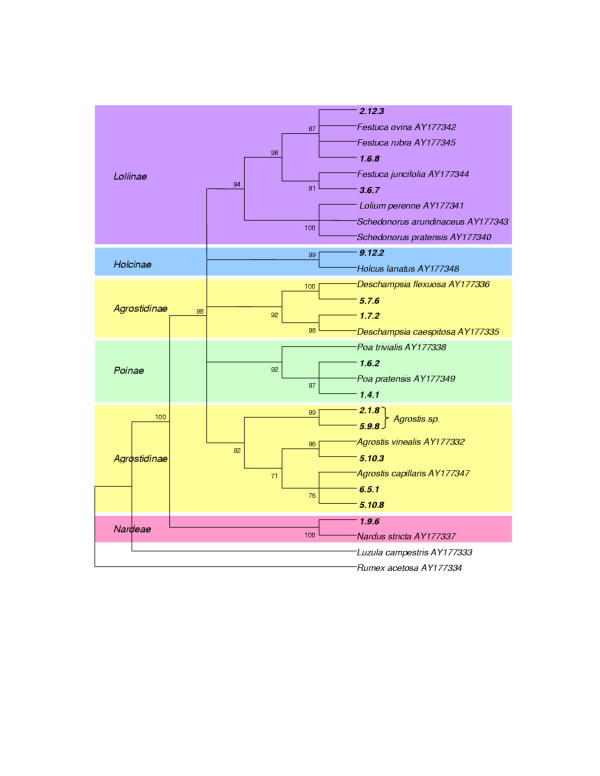

PCR products from root samples representing each trnL intron RFLP type were sequenced to verify identity. The nucleotide sequence from a root identified as H. lanatus was 34 bp longer than our database key sequence, confirming the need for caution in assigning species names to RFLP types. The alignment of eleven A. capillaris trnL intron sequences shows little intraspecific variation (1 bp difference in 500 bp). A phylogenetic tree to compare trnL sequences from roots with key species supports current taxonomic relationships in the Poaceae (Fig. 1). Since the trnL sequence of the unassigned samples grouped with Agrostis we labelled these unknowns as Agrostis sp.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships within the Poaceae based on trnL intron sequences from this study. Individual roots from field sampling are shown in bold with a unique identifier. Coloured blocks denote subtribes. The consensus tree was constructed using maximum parsimony in MEGA version 2.1 [13]. Bootstrap percentages from 100 replications are indicated.

Fluorescent fragment length polymorphism

Capillary electrophoresis of fluorescently labelled trnL PCR products was tested as a high-throughput method of discriminating the ten species detected at the field site. Table 3 shows the range of fragment lengths obtained from at least three samples of each taxon where available. Fragment lengths for most taxa varied within the range of resolution (+/- 2 bp) and seven species could be unambiguously defined. N. stricta and Agrostis sp. had length variants of 3 bp and 6 bp respectively, resulting in an overlap between the fragment lengths of N. stricta, Agrostis sp. and P. pratensis. However, variation in the 5' terminal fragment from Hsp92II digestion can resolve all 3 species.

Table 3.

Range of estimated fragment lengths for Sourhope grass species determined by capillary electrophoresis of fluorescent dye-labelled trnL PCR.

| Grass species | trnL PCR length (bp) |

| Agrostis capillaris | 496.5–497.5 |

| Agrostis vinealis | 500.7–501.9 |

| Festuca rubra | 612.6–614.8 |

| Festuca sp. | 616.0–618.3 |

| Deschampsia caespitosa | 618.9–620.7 |

| Nardus stricta | 626.8–629.8 (337a) |

| Agrostis sp. | 624.2–630.4 (528–535a) |

| Poa pratensis | 629.7–630.8 (539a) |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 648.8–649.6 |

| Holcus sp. | 652.4 |

a Hsp92II 5' terminal fragment length

Identification of plant species from root DNA by trnL PCR fluorescent fragment length polymorphism (FFLP) represents a considerable advance on the use of agarose gel based PCR-RFLP techniques by offering high resolution, which removes the need for multiple enzyme digests. Also, fewer steps and more automation can reduce sources of error when dealing with large numbers of samples. Further savings could be made by combining, in one well, the fluorescent products of both root and associated microbial products if different terminal dyes are used. Multiplex PCR is also an option if primers pairs can be designed to avoid interaction and anneal efficiently at the same temperature. Additionally, the peak area of diagnostic fragments allows relative quantification of each amplification product in mixed samples [10].

Conclusions

A molecular identification key based on RFLP of the plastid trnL intron was successfully developed and utilised to identify a large number of small root fragments sampled from an upland grassland. This procedure could be adapted to any field system in which it is desirable to identify plant species from roots, or other plant material insufficient for morphological taxonomy. ITS sequence data can be used for identification if unexpected patterns occur. Furthermore, by employing capillary electrophoresis of fluorescently labelled trnL PCR products, large numbers of samples can be rapidly processed with a higher precision than agarose gel methodologies. Semi-automated throughput of > 100 samples per day at a resolution of +/- 2 bp makes this method ideally suited to the molecular characterisation of both root and associated microbes. With the ability to identify individual roots in soil we can begin to address questions of how below-ground processes influence community diversity and composition at a small scale.

Methods

Reference plant material

Plant material from species known to occur at the field site under investigation was collected in order to develop a trnL intron sequence database. Closely related species were included where possible or available. (Agrostis vinealis, Deschampsia caespitosa, Deschampsia flexuosa, Festuce ovina, Festuca juncifolia, Festuca arundiaceae, Holcus lanatus, Luzula campestris, Nardus stricta, Phleum pratense, Poa trivialis). The trnL intron sequences for Agrostis capillaris (AY177347), Festuca rubra (AY177345), Poa pratensis (AY177349) were available from a previous study [6].

DNA isolation and PCR-RFLP

DNA was isolated from plant tissue samples using the CTAB method [11]. The plastid trnL intron was amplified from plant DNA using the primer pair c and d [12]. Amplifications were performed in 50 μL volume containing 2 μL of template DNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 10 pmoles of each primer, 100 μM dNTPs, 2 mM MgCl2 and 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). PCR program consisted of 30 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1.5 min) on a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research Inc.). Each amplification reaction was analysed by electrophoresis in TBE buffer on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel and visualised under UV light after staining with ethidium bromide. PCR products were sequenced in both directions using BigDye and either the forward or reverse PCR primer and resolved on an ABI 377 automated sequencer according to the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems). Theoretical digests to discriminate between taxa were performed using Lasergene (DNAstar). Fragment sizes of less than 50 bp or differences in fragment sizes of less than 20 bp were not considered informative for agarose gel electrophoresis. Theoretical restriction patterns were confirmed by digestion of PCR product with the restriction endonucleases found to be most discriminating. Digests were performed at 37°C for at least 2 h according to manufacturers' instructions. The double digest with NlaIV and DdeI was performed in Promega buffer B. BfaI and NlaIV were obtained from New England Biolabs; DdeI, HinfI, Hsp92II and XmnI from Promega. Fragments were separated on a 2 % (w/v) Agarose:Metaphor agarose (FMC Bioproducts, UK) (1:1) gel in TBE buffer and visualised by staining with ethidium bromide.

Field sampling and identification of roots

Field sampling took place on Fassett Hill at Sourhope (National Grid Reference NT 852207), an upland grassland in the Scottish Borders. Forty soil cores (10 cm diameter) were taken from a 14 m × 12 m plot. Twenty four root fragments were randomly selected from a 1 cm cube of soil from each core and frozen prior to DNA isolation. The Qiagen DNeasy 96 Plant Kit was utilised for high-throughput DNA isolation from the 960 spatially referenced root fragments following the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was stored at -20°C prior to amplification.

The trnL intron was amplified from root DNA, digested with appropriate enzymes as described above, and compared to the RFLP key. For roots with RFLP patterns which did not match any database taxa, the nuclear ribosomal ITS region was amplified using the same PCR protocol as for the trnL intron but with primers ITS4 [9], and ITS1P (AACCTTATCATTTAGAGGAAGG), newly designed to preferentially amplify grasses but not fungi. Sequencing in both directions as above and comparison to GenBank using BlastN [8] allowed identification of unknown taxa.

Capillary electrophoresis of fluorescently-labeled trnL PCR products

For fluorescent detection of trnL PCR products the region was amplified from plant DNA as above except the forward primer was labelled at the 5' end with WellRED Beckman Dye D2-PA (Proligo). PCR products were resuspended in deionized formamide following ethanol precipitation. An aliquot of 0.5 – 2.0 μL was added to 30 μL SLS loading solution containing 0.1 – 0.2 μL Size Standard 600 (Beckman-Coulter). Fluorescently labelled fragments were separated by capillary electrophoresis and detected by laser-induced fluorescence using the CEQ 8000 automated gene sequencer (Beckman-Coulter). Samples were denatured at 95°C for 2 min before injection at 4.8 kV for 40 s and separation for 70 min. Fragments were sized by comparison to the internal standard using CEQ 8000 software for Fragment Analysis. At least three samples of each taxon, previously identified by trnL PCR-RFLP, were analysed to assess the ability to discriminate between species by trnL fragment length.

List of abbreviations

RFLP – Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism, FFLP – Fluorescent Fragment Length Polymorphism, ITS – Internal Transcribed Spacer

Authors' contributions

KPR drafted the manuscript and participated in field collection, DNA isolation and method development. JMD assisted with DNA isolation, polymerase chain reaction and gel electrophoresis. JPWY conceived and supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tim Daniell, Julie Squires and Irene Watson for assistance with field collection. Barbara Smith and Celina Whalley helped with capillary electrophoresis and fragment analysis. This work was funded by the Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department (SEERAD) MICRONET programme.

Contributor Information

Karyn P Ridgway, Email: kpr1@york.ac.uk.

Janette M Duck, Email: janettemduck@yahoo.com.

J Peter W Young, Email: jpy1@york.ac.uk.

References

- Moore PD. Roots of diversity. Nature. 2003;424:26–27. doi: 10.1038/424026a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielly L, Taberlet P. The use of chloroplast DNA to resolve plant phylogenies – noncoding versus rbcL sequences. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1994;11:769–777. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner I, Brodbeck S, Buchler U, Sperisen C. Molecular identification of fine roots of trees from the Alps: reliable and fast DNA extraction and PCR-RFLP analyses of plastid DNA. Molecular Ecology. 2001;10:2079–2087. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojoma M, Kurihara K, Yamada K, Sekita S, Satake M, Iida O. Genetic identification of cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.) based on the trnL-trnF chloroplast DNA. Planta Medica. 2002;68:94–96. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsrud P, Rikkinen J, Lindblad P. Field investigations on cyanobacterial specificity in Peltigera aphthosa. New Phytologist. 2001;152:117–123. doi: 10.1046/j.0028-646x.2001.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenkoornhuyse P, Ridgway KP, Watson IJ, Fitter AH, Young JPW. Co-existing grass species have distinctive arbuscular mycorrhizal communities. Molecular Ecology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Linder CR, Moore LA, Jackson RB. A universal molecular method for identifying underground plant parts to species. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9:1549–1559. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: G Innis MA, DH Snisky JJ, White TJ, editor. Protocols: a Guide to Methods and Applications. San Diego: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Leuders T, Friedrich MW. Evaluation of PCR amplification bias by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of small-subunit rRNA and mcrA genes by using defined template mixtures of methanogenic pure cultures and soil DNA extracts. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2003;69:320–326. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.320-326.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardes M, Bruns TD. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes – application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Molecular Ecology. 1993;2:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1993.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberlet P, Gielly L, Pautou G, Bouvet J. Universal primers for amplification of 3' noncoding regions of chloroplast DNA. Plant Molecular Biology. 1991;17:1105–1109. doi: 10.1007/BF00037152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen IB, Nei M. MEGA2: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1244–1245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]