Abstract

Background

Bacterial mercury resistance is based on enzymatic reduction of ionic mercury to elemental mercury and has recently been demonstrated to be applicable for industrial wastewater clean-up. The long-term monitoring of such biocatalyser systems requires a cultivation independent functional community profiling method targeting the key enzyme of the process, the merA gene coding for the mercuric reductase. We report on the development of a profiling method for merA and its application to monitor changes in the functional diversity of the biofilm community of a technical scale biocatalyzer over 8 months of on-site operation.

Results

Based on an alignment of 30 merA sequences from Gram negative bacteria, conserved primers were designed for amplification of merA fragments with an optimized PCR protocol. The resulting amplicons of approximately 280 bp were separated by thermogradient gelelectrophoresis (TGGE), resulting in strain specific fingerprints for mercury resistant Gram negative isolates with different merA sequences. The merA profiling of the biofilm community from a technical biocatalyzer showed persistence of some and loss of other inoculum strains as well as the appearance of new bands, resulting in an overall increase of the functional diversity of the biofilm community. One predominant new band of the merA community profile was also detected in a biocatalyzer effluent isolate, which was identified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The isolated strain showed lower mercury reduction rates in liquid culture than the inoculum strains but was apparently highly competitive in the biofilm environment of the biocatalyzer where moderate mercury levels were prevailing.

Conclusions

The merA profiling technique allowed to monitor the ongoing selection for better adapted strains during the operation of a biocatalyzer and to direct their subsequent isolation. In such a way, a predominant mercury reducing Ps. aeruginosa strain was identified by its unique mercuric reductase gene.

Background

Phylogenetic profiling of microbial communities based on sequence specific separation of phylogenetic marker genes (mainly the 16S rRNA gene or the 16S-23S ribosomal intergenic spacer region) is widely used in microbial ecology to study changes in community diversity in response to environmental parameters or experimental perturbations. However, physiological traits are often dispersed across the phylogenetic tree, and so conclusions regarding the processes driven by the microbes in question cannot be drawn. Functional gene profiling has the potential to provide information about the functional diversity of microbial populations with respect to a key enzyme of interest, and therefore should be much more meaningful. There are only very few reports of functional community profiling so far, two recent examples being the pufM gene of photosynthetic marine bacteria in a permanently frozen Antarctic lake [1] and the amoA gene of ammonia oxidizers in soil [2]. Engineered systems contain enriched specialized populations which have often been subject to prolonged selection pressure and should therefore provide especially good applications for functional community profiling.

Recently a new process for remediation of mercury contaminated wastewater has been developed [3] and demonstrated in technical scale [4]. It is based on the microbial mercury resistance (mer) operon [5-8]. Mercury resistant bacteria were immobilized on inert carrier material within a packed bed bioreactor and shown to remove up to 99 % of incoming ionic mercury from raw industrial wastewater by reducing it to elemental mercury which accumulated outside of the bacterial cells in the carrier material [3]. The process was scaled up to a biocatalyzer volume of 1000 L and demonstrated for 8 months at a chloralkali factory, where it was highly efficient and stable against fluctuations in inflow parameters inherent to the production process [4,9,10]. The key enzyme of this process is the mercuric reductase, encoded by the merA gene. Profiling the diversity of merA genes in the bioreactor community allows to focus directly on that part of the microbial community relevant for the process. Since the concentrations of mercury ions in the wastewater were rather high (4.3 mg L-1 on average), microorganisms not having a detoxification mechanism were not able to survive in the bioreactor. For this particular example therefore one would expect the merA profile to give a fairly complete picture of the most abundant members of the microbial community present.

Previous culture independent analyses of the biocatalyzer system were based upon phylogenetic markers like the 16S rRNA gene [4,9] or the internal transcribed spacer region between 16S and 23S (RISA, [10-13]). However, any information on the mercury resistance of individual community members relied on their isolation and subsequent physiological characterization, a tedious approach which can be very biased. In the biocatalyzer studied here [10] the more abundant effluent isolates have been identified by comparing their RISA fingerprints to the community fingerprint. These isolates were tested for their mercury resistance levels and shown to grow on plates containing up to 10 mg HgCl2 per liter. However, determination of mercury resistance levels is not straightforward, since media composition and inoculum density have a large influence. Moreover, especially at low mercury concentrations, tolerance mechanisms for mercury can play a role besides enzymatic mercury reduction (e.g. unspecific adsorption to cell surface components; indirect reduction by cell metabolites; [14,15]) Since active mercury reduction in microorganisms is performed only by the mercuric reductase enzyme [16] encoded in the conserved merA gene, a more straightforward way to identify the abundant mercury reducers within the biofilm community was feasible, which was independent of cultivation. Here we report the development of a community profiling method for merA and its application to monitor changes in the functional diversity of mercury reducing biofilm communities.

Results

Primer Design and PCR protocol for merA

Conserved primers for the merA gene of Gram negative bacteria and a PCR protocol for amplification of merA from a diverse mixture of Proteobacterial merA genes were developed based on a sequence alignment of 30 merA sequences from Gram negative bacteria. Suitable priming regions could not be identified for Gram-positives due to their high merA sequence variability. For Gram-negatives, the end part of the sequence, coding for the reaction center, could be used for primer design. Two highly conserved regions in a distance of more than 200 bp were identified. However, the region of identical nucleotide sequences was only 10 bp long. Degenerate primers are prone to produce band multiplication on TGGE. Therefore, ambiguous nucleotide positions were eliminated in the following way: Where the primer target sequence showed a C or T, the primer got a complementary G, since this can also bind to T. Accordingly, where the primer target sequence showed a A or G, the primer got a complementary T, since this can also bind to G. To reduce the probability for mismatches with unknown merA sequences, relatively low annealing temperatures were applied.

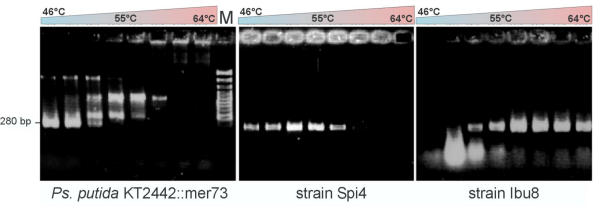

Primer annealing temperatures were tested between 46.6 and 63.8°C. Some merA genes could not be amplified using annealing temperatures above 50°C, while others required more than 55°C (Fig. 1). The latter may have been caused by interactions with non-target genomic DNA of the respective strains. The high GC content of the merA sequences (average of 64%) may have played a role as well. Thus, the PCR protocol consisted of an initial high-temperature (59–55°C) annealing touch down step to amplify sequences requiring high annealing temperatures (e.g. Spi3, Ibu8) followed by a subsequent low-temperature annealing step (46°C). In such a way it was possible to amplify the merA fragment from all Gram-negative isolates in the same PCR reaction. Using this protocol, all Pseudomonas strains (Spi3, Spi4, Elb2, Elb5, Kon12, Ibu8, Spi11, Bro12) and the mercury resistance transposons and plasmids used as controls showed one clear amplicon of approximately 280 bp length without any side products (Fig. 2). One strain (Bro62) showed a second, larger amplicon. Two strains (Spi5 and Spi7) had aberrant fragment lengths, possibly caused by variations in the sequence and length of the merA gene. For example, strain Spi7 had an amplicon of. >400 bp length which yielded nevertheless a distinct band on TGGE (Fig. 3). Strain Spi7 has been identified as a Sphingomonas sp. (Alphaproteobacteria)[17], and thus has no close phylogenetic relationship to the strains with sequenced merA genes which were used for primer design. Interestingly, the other two aberrant PCR reactions also occurred with genera other than Pseudomonas: Spi5 has been identified as a Klebsiella sp. and Bro62 as Citrobacter freundii [10].

Figure 1.

Effect of PCR annealing temperature (between 46°C and 64°C) on merA amplification efficiency with primers GC-merAf and merAr. The ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels show different annealing temperature dependencies for merA PCR products of representative isolates. (1) Ps. putida KT2442::mer73 [29] had its optimum al low annealing temperature; (2) P. putida Spi4 and most other strains tested worked best at medium annealing temperature; (3) P. stutzeri Ibu8 failed at low annealing temperatures but worked well at high temperatures.

Figure 2.

Amplification of merA fragments from mercury resistant strains and cloned mer operons using an optimized PCR protocol with primers GC-merAf and merAr on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. On the left hand, environmental isolates (black), biocatalyzer inoculum strains (violet) and the main invader (red) are shown. On the right hand, merA-containing vectors kindly provided by M. Osborn [14] are shown. For strain identification of inoculum strains and invader see Fig. 5; environmental isolates were Klebsiella sp. Spi5; P. putida Elb5; Citrobacter freundii Bro62; Sphingomonas sp. Spi7.

Figure 3.

Separation of merA amplicons (primers GC-merAf and merAr) on a silver-stained TGGE gel. All strains showed clearly distinguishable merA-TGGE fingerprints. See Fig. 5 for strain identification. M, mix of PCR products from all eight strains.

merA-TGGE fingerprints of mercury resistant isolates

Amplicons generated by the merA specific PCR were separated on TGGE gels. Every strain tested yielded one dominant band with a migration behavior different from that of all other strains (Fig. 3). Thus, strain specific merA fingerprints were obtained. Often one or two secondary bands were present which were always following the primary band like a shadow. This indicated a non-linear melting order of the molecule down to the GC-clamp during TGGE migration, likely due to the partially high GC content. In some cases (Elb2, Spi4, Spi3) weak side bands at varying distance to the primary band were found which may have been caused by amplification errors during early phases of the PCR reaction which were subsequently amplified further and thus yielded separate bands on TGGE.

Analysis of the merA sequences of the inoculum strains

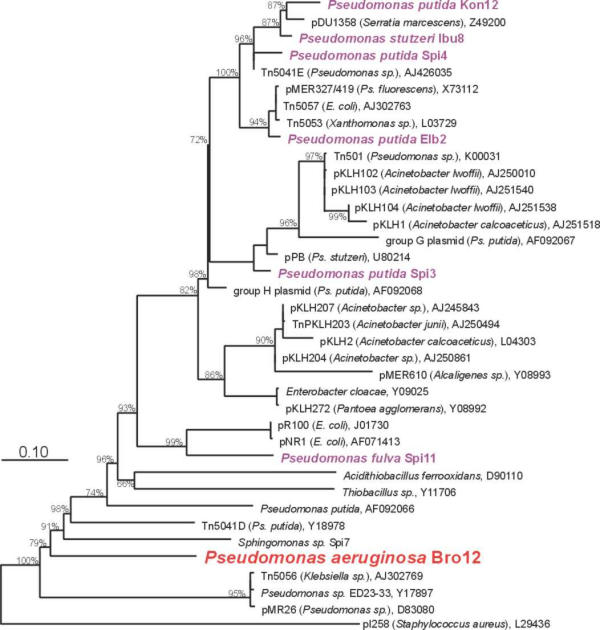

To obtain complete sequences for the merA genes of the inoculum strains and several strong mercury reducing bioreactor isolates, a large set of partly overlapping primers was used (Fig. 4, Table 1), some of which binding in conserved genes outside of merA. After sequencing of the various amplified fragments, the complete merA genes were assembled and aligned. Fig. 5 shows a phylogenetic tree for the 30 published merA sequences used for the design of the conserved merA-TGGE primers as well as for the six Pseudomonas sp. used as inoculum for the technical scale biocatalyzer (Kon12, Ibu8, Spi4, Elb2, Spi3, Spi11), the isolate Sphingomonas sp. Spi7 (not used as an inoculum strain) and the invading strain P. aeruginosa Bro 12 (see below).

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of a typical broad-spectrum mercury resistance operon of Gram-negative bacteria and the location of primers (arrowheads) used for amplification of merA. The merA stretch used for TGGE analysis is marked orange. R, regulator protein merR; OP, operator/promotor region and start of transcription; T, periplasmic transport protein merT; P, membrane bound transport protein merP; A, mercuric reductase merA; B, mercuric lyase merB; D, regulatory protein merD.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for sequencing of merA genes and for merA-TGGE.

| mer primers | Direction | Nucleotide sequence (5' to 3') |

| primers used for sequencing | ||

| T1 | Forward | GTCTGGATCGGCAACTTGA |

| P1 | Forward | GGCTATCCGTCCAGCGTCAA |

| A1 | Forward | ACCATCGGCGGCACCTGCGT |

| A5 | Reverse | ACCATCGTCAGGTAGGGGACCAA |

| A7 | Reverse | TGGCGCATTGACAGTBGACCC |

| A9 | Forward | GAAYTGGATCCAGACGGCKG |

| A10 | Reverse | GATCATGATCTTGGACGGCACACA |

| D1 | Reverse | TCATGGCAAACTCTCCGC |

| TGGE primers (GC-clamp in italics) | ||

| GC-merAf | Forward | CCCGCCGCCCCGCCCGCCGCCCCGCCCCGCCGCCCGCCTTGGAGAACGTGC |

| merAr | Reverse | ACGTCCTTGGTGAAGGTCTG |

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationship between merA genes of Gram-negative bacteria. The tree was based on an alignment of 30 published and eight newly determined nucleic acid sequences of merA genes and calculated with the maximum likelihood algorithm. Bootstrap values above 65 % are given at the branching points. The bar indicates one nucleotide exchange per ten nucleotide positions. EMBL accession numbers are given after the names. Inoculum strains are shown in violet, Ps. aeruginosa Bro12 is the invading strain identified on the basis of its band in the merA community profile.

The overall similarity between these merA sequences is very high. Since the mer operon is often located on transposable elements or plasmids, it is not surprising to find merA genes from phylogenetically distant organisms to be highly related, e.g. the mercuric reductase genes from pMER327, Tn5057 and Tn5053 are identical, although they were found in P. fluorescens, E. coli and Xanthomonas sp., respectively.

However, in accordance with the results from the merA-TGGE fingerprints, every strain investigated here had a sequence distinct from that of all other strains and from published sequences. The inoculum strain Spi3 carried a mercuric reductase very closely related to the one of Tn501 (517 of 527 amino acids identical, 95.7 % DNA sequence identity, Fig. 5). The strains Ibu8 and Kon12 showed a very close relationship to a mercuric reductase from plasmid pDU1358 (97.5 and 99.0 % nucleotide identity, respectively). The merA sequences of strains Elb2 and Spi4 were more distantly related to pDU1358 (91.1 and 93.9 % nucleotide identity). Strain Spi11 had a remote similarity to a mercuric reductases from E. coli plasmids (<80 % nucleotide identity). The strain Ps. aeruginosa Bro12, which became predominant during biocatalyzer operation, had the lowest similarity to already known mercuric reductases (around 70 % nucleotide identity). Only 402 nucleotides, resp. 133 amino acids could be identified for Bro12 because the mer-specific sequencing primers showed a low coverage in this case.

Sequence analysis of the merA genes of the inoculum strains for the binding region of the merA-TGGE primers showed that three strains carried a possibly critical mismatch in the primer binding site at the second position of the 3'-end of the forward primer (T instead of G). However, these strains (Spi3, Spi4, Elb2) showed no indication for reduced amplification efficacy. Strain Spi3 even required annealing temperatures above 55°C.

Functional profiling of mercury reducing biofilms

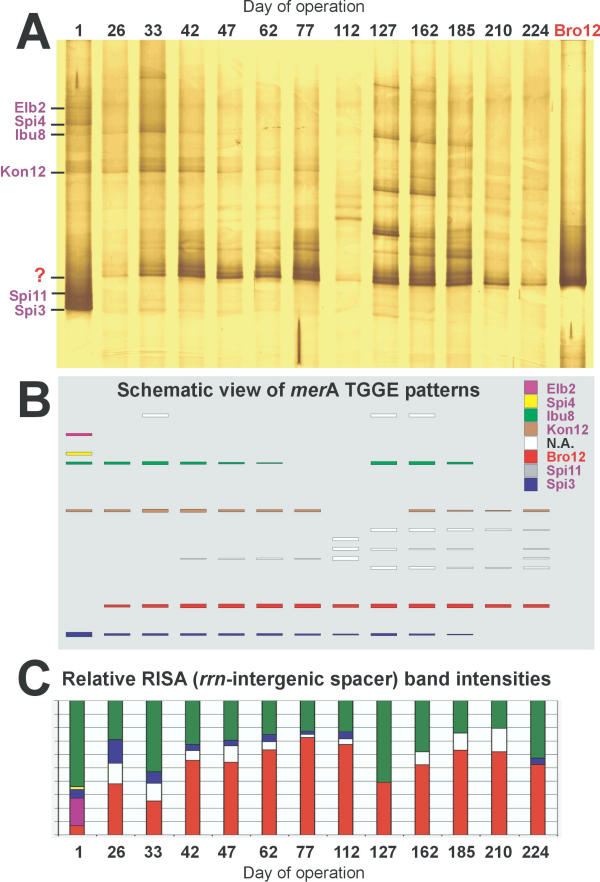

Amplification of merA from mercury reducing biofilm communities of the technical scale biocatalyzer yielded clear fingerprints after separation by TGGE (Fig. 6A,6B). Bands from five of the six inoculum strains (Elb2, Spi4, Ibu8, Kon12, Spi3) could be identified on day 1, strain Spi11 was not detectable. This was probably due to its low abundance in the inoculum caused by problems with cultivation (Wagner-Döbler, personal comm.). During the following 224 days of pilot plant operation, large changes in the merA fingerprints were observed. Spi4 and Elb2 were never again detected. The relative abundance of Spi3, which was a dominant component of the inoculum, gradually decreased to below detection. Bands representing the merA genes from Ibu8 and Kon12 were detected up to the end of operation at varying intensities. In addition to the merA amplicons from the inoculum strains, additional bands were observed on the merA-TGGE fingerprints, especially after day 127. Thus, the initial diversity of 5 merA bands on day1 increased to 7 – 8 merA bands during the later phase of pilot plant operation. The strongest additional band (designated "?" in Fig. 6A) was already weakly present on day 1 and became the predominant merA gene of the biofilm community throughout the operating period.

Figure 6.

Community profiles of merA amplicons from a technical scale biocatalyzer over 224 days of operation at a chloralkali factory. A, Silver-stained TGGE gel with DNA of separated merA PCR products of biofilm samples. The numbers on the top of the lanes indicate the days since operation started. Bro12 indicates the merA PCR product amplified from genomic DNA of Ps. aeruginosa Bro12. Most inoculum strains (lane 1), disappeared and returned from time to time. The predominant signal at position (?) did not belong to any inoculum strain, but was identical to that of the invader Ps. aeruginosa Bro12. B, below is a schematic representation of the identified signals. Different colors represent different strains. C, at the bottom are the corresponding RISA results of the rrn-intergenic spacer region, displayed with a corresponding color code (N.A. = not analyzed).

Phylogenetic versus functional profiling of mercury reducing biofilms

In Fig. 6, the results from the merA-TGGE functional community profiling (Fig. 6A,6B) can be compared to the results of a phylogenetic profiling of the same community DNA which was based on the ribosomal intergenic spacer region (RISA, [10]) (Fig. 6C). In both community fingerprints, the invading strain Bro12 is identified as the predominant organism. Moreover, with both methods Elb2 and Spi4 could only be detected on day 1, and the inoculum strain Spi11 could not be refound at all. Differences between the two profiling methods became apparent for the other strains. The merA-TGGE approach detected bands for Ibu8, Kon12 and Spi3 in most samples. However, the RISA method completely missed Kon12, while Ibu8 appeared sometimes almost as abundant as Bro12. The detection of Spi3 was in agreement among both methods for most samples with the exception of day 1, where according to the merA TGGE the biocatalyzer community appeared to be dominated by Ps. putida Spi3, while it was only a minor component on the RISA fingerprint. In the coming months, the number of detectable strains dropped to 2–4 strains with RISA, but was around 4–8 strains for the merA TGGE fingerprint. Several new bands appeared temporarily, indicating a succession of strains and an increase in diversity of merA amplicons in the technical scale biocatalyzer. Especially from day 127 on, the diversity of merA increased for approximately two months before Bro12 regained dominance. This temporary increase in diversity was not visible with RISA.

Identification of the dominant merA signal

Effluent bacteria from the biocatalyzer were enumerated using the spread plate technique and their mercury resistance levels determined on media containing mercury [10]. Fingerprints using the merA-TGGE PCR were generated from mercury resistant isolates and compared to merA-TGGE community fingerprints. The fingerprint of one predominant isolate (Bro12) matched with the most prominent band (designated as '?' in Fig. 6A) in the merA community profile. Partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene of Bro12 revealed 99.6 % sequence identity to Ps. aeruginosa [10,12]. This identification was supported by a typical bluish-gray color zone around aged colonies. The latter should be due to excretion of pyocyanin, which is very characteristic for Ps. aeruginosa [18].

Discussion

Primer design and diversity of merA sequences

The mercuric reductase-specific PCR-TGGE was based on the selection of wobble nucleotides at ambiguous sequence positions and a touch-down PCR protocol allowing amplification of merA sequences with low and high temperature optimum in the same PCR reaction. It was a useful tool to obtain specific merA fingerprints from Gram-negative bacteria and was applicable to monitor their functional diversity in complex microbial communities. The Gram-positive bacteria had to be excluded from this study since only few mercuric reductases are known for them, and they are quite different from those of Gram-negative bacteria [14] and highly diverse among themselves [19]. However, Gram-positives have never been observed as prominent mercury reducers in the biocatalyzer studied here [10]. The primer design was based on 30 mercuric reductase sequences from the EMBL database, and the PCR gave a product with all tested mercury resistant isolates. These isolates were later shown to have merA genes which were highly similar, but not identical to the previously published sequences. Some of the investigated mercury resistant strains considerably extended the known range of sequence variations of mercuric reductases among Gram-negatives, especially the new isolates Sphingomonas sp. Spi7 and P. aeruginosa Bro12.

Comparison between functional (merA-TGGE) and phylogenetic (RISA) community profiling

Both merA-TGGE and RISA have their limitations and biases. The merA-TGGE suffered from the difficult PCR and the much higher risk of primer mismatch. With RISA, the equality of amplification efficacy was impaired by the highly variable length of the products. Hence, both techniques can only be considered as semi-quantitative. However, for the mercury reducing biofilms investigated here, phylogenetic [10] and functional community profiling methods yielded largely similar results. The same inoculum strains were detected with both methods (with the exception of Kon12), although their relative abundance suggested by band intensities differed between RISA and merA-TGGE community fingerprints. The carrier of the predominant merA gene in the biofilm, Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bro12, was identified as a predominant member of the community based on RISA as well. Invaders were also detected with both methods, although the merA-TGGE appeared to be more sensitive. The concordance between phylogenetic and functional profiling of biofilm communities from the biocatalyzer shown here further supports the conclusion drawn already previously [10] that the presence of toxic mercury in the industrial wastewater entering the system at a high flow rate exerted a continuous selective pressure which allowed only mercury resistant bacteria to maintain high population densities. Consequently, the performance of the biocatalyzer was not impaired by the observed succession of strains, neither in small laboratory reactors nor in the technical scale reactor.

The origin of the intruders

Toxic mercuric loads, for instance released by volcanic activity [20], have been present on earth since the beginning of life and therefore, bacteria have evolved mechanisms of resistance to several different chemical mercury forms. Such bacteria can be found across a wide range of Gram-negative and Gram-positive genera and from diverse natural and man-made environments. The genes of the mer operon are not always located on the bacterial chromosome but are often found on transposons and plasmids, adding to the mobility of mercury resistance genes between species. Hence, mercury resistance is ubiquitous, even in environments without notable mercury loads [14]. Every environment in contact with the biocatalyzer, especially the air, may therefore introduce hitherto unknown mercury reducers [21]. The waste water itself was not likely to have been a source of mercury-resistant invaders. Originating from the electrolysis cells, it was virtually carbon- and nitrogen-free, temporarily carried a massive load of chlorine and the pH approximated 2. Consequently, no bacteria could be enriched from the waste water. It is unlikely that the invading strains arrived through the outflow, because the water current was very fast (a few 1000 L h-1) and the outlet of the biocatalyzer was an overflow, thus backwards growth of bacteria was not possible. Invasion of environmental bacteria might however have occurred via the broth tank or the neutralization tank, which were both in prolonged contact with air.

Mercury resistance in biofilms

The predominant mercury reducer in the biocatalyzer, Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bro12, showed slow growth and a medium mercury reduction rate in pure liquid culture tests compared to the inoculum strains [12]. Apparently, the assumption that the best biocatalyzer strain should have the highest mercury reduction rate in liquid media did not hold true. Since the Hg2+ concentration in the biocatalyzer inflow was fluctuating around a mean of 4.2 mg L-1 and extreme inflow concentrations occurred only rarely and were short-lived [10], Bro12 may indeed have been well adapted to the prevailing Hg2+ concentration in the system. During mercury peaks the strain Bro12 may also have been protected by the still persisting and active community of highly resistant inoculum strains [12]. In addition, however, resistance to heavy metal stress (copper, lead, or zinc) has been shown to be up to 600 times higher for Ps. aeruginosa cells forming biofilms than in planktonic cells due to the buffering effect of the extracellular polymeric substance produced in the biofilm [22]. A similar effect might be expected in the case of mercury. The species Ps. aeruginosa is present in many aquatic habitats [23], but also represents an opportunistic pathogen which frequently forms biofilms [24,25]. Such biofilms are comprised of thick EPS (extracellular polysaccharide substance) matrices which protect the cells effectively from antibiotics and disinfectants, and may also buffer the toxicity of Hg2+ in the biocatalyzer environment investigated here [22].

Conclusion

Molecular monitoring of a key functional gene within a bacterial community is clearly favorable even if its members are culturable. Changing culturability and media selectivity may massively bias the results of cultivation based analyses. Functional profiling of the merA gene from technical biofilms showed a microbial community similar to the one identified on the basis of the ribosomal RNA gene interspacer region, confirming the presence of a strong selective pressure exerted by mercury toxicity. By linking the molecular data back to pure cultures we were able to identify and isolate the dominant mercury reducing strain from the technical scale biocatalyzer based on its unique mercuric reductase gene. Strain Ps. aeruginosa Bro12 showed slow growth and medium mercury resistance in liquid media, but was apparently extremely well adapted to the biofilm environment in the biocatalyzer.

Methods

Biocatalyzer sampling and DNA extraction

The biocatalyzer contained 1,000 L of pumice granules covered by a microbial biofilm and maintained in a closed vessel as specified previously [4]. The waste water entering the system typically contained a mercury load of 2 – 10 mg L-1 with a mean concentration of 4.2 mg L-1 and up to 50 g L-1 chloride and approximately 6 mg L-1oxygen. The efflux of the biocatalyzer passed an activated carbon filter which removed remaining mercury both by physical adsorption and by microbial reduction. The system was inoculated with six strains, four were Pseudomonas putida (Spi3, Spi4, Kon12, Elb2), one Pseudomonas stutzeri (Ibu8), and one Pseudomonas fulva (Spi11) as described previously [10]. In the following eight months of operation, solid samples were taken from the lowest accessible horizon of the biocatalyzer, close to the inflow (approximately 30 cm above the bottom). Sampling was done with a hollow sampling lancet picking approximately 4 cm3 of the pumice granules. Biofilms were removed from the carrier surface by vigorous mixing in 2 ml NaCl solution (15 g L-1). Then, DNA was extracted using guanidium thiocyanate as described previously [26].

Sequencing of merA genes

Total cellular genomic DNA was isolated from 1 ml of overnight cultures of the involved mercury reducing strains grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 30°C using the Nucleospin C+T Extraction Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The merA region was PCR-amplified using alternative primer pairs that were designed after alignment of all available Gram negative mer operon sequences from the EMBL database with ClustalW. To compensate for possible primer failures on unknown merA sequences, several specific primers were used outside the merA gene. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1, the corresponding location of the priming sites in the mer operon is depicted in Fig. 4.

The amplification reactions were performed in a total volume of 50 μl by using a thermal cycler (Mastercycler personal, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The PCR reaction mixture contained 1 × Qiagen PCR Master Mix (QIAGEN, Germany), 1 μl of template DNA and 0.5 μM of each primer. The PCR protocol consisted of a pre-denaturation step at 94°C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 56°C for 30 s, and an extension step at 68°C for 4.5 min. Positive PCR products were sequenced by the GATC BIOTEC AG (Konstanz, Germany) with the common enzymatic Sanger method using ABI 3700 sequencing instruments and the same primers as before. The obtained sequences were assembled to complete merA sequences and submitted to EMBL with accession numbers AJ418049-AJ418057.

Phylogenetic analyses

The phylogenetic tree for merA sequences was constructed with the ARB package using the implemented Phylip software [27]. The tree was based on 30 nucleic acid sequences downloaded from the EMBL database and 7 additional sequences determined here. The tree was calculated with the maximum likelihood tool. Bootstrap values were presented next to the branching points if they were above 65%.

The mercuric reductase-specific PCR and TGGE

Amplification was performed with a GeneAmp System 9700 (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) using an initial touchdown PCR step of 10 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 59–55°C for 20 s and 68°C for 20 s, afterwards continuing with 45 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 46°C for 20 s and 68°C for 20 s. The PCR reactions (20 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 5% DMSO (v/v), 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 100 μM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 0.4 μM of forward primer GC-merAf and reverse primer merAr, 0.5 units of recombinant Taq DNA polymerase (LifeTechnologies, Paisley, UK), and 1 μl template. The PCR products usually approximated 280 bp and were separated on a TGGE Maxi System (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) against a temperature gradient of 36 – 51°C. A pre-run of 10 min at 10 V to allow gradient stabilization was followed by a 3.5 h electrophoresis at 400 V. The TGGE gel was a 0.8 mm-polyacrylamide gel (6% w/v acrylamide, 0.1% w/v bis-acrylamide, 8 M urea, 20% v/v formamide, 2% v/v glycerol) with 1 × MN buffer (20 mM MOPS, 10 mM NaOH). Silver staining was used to visualize the DNA bands [28].

Author's contributions

ADMF wrote the manuscript, developed the method and carried out the PCR-TGGE monitoring analysis. WF and BVP amplified and sequenced merA genes. HvC did the biofilm sampling, DNA extraction and isolation of effluent bacteria. IWD designed and advised the project and significantly contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

A big 'Thank You' to Ying Li, Harald von Canstein and Johannes Leonhäuser for running the biocatalysers. We gratefully acknowledge Mark Osborn for providing DNA of several archaetypical merA genes. This work was supported by a grant from a European Communities EC project QLK3-1999-01213. ADMF was supported by a grant from the European Communities EC project BACREX (QLK3-2000-01678).

Contributor Information

Andreas DM Felske, Email: Andreas@bacrex.com.

Wanda Fehr, Email: wanda.fehr@web.de.

Björg V Pauling, Email: bjoerg.pauling@web.de.

Harald von Canstein, Email: hari@kais.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Irene Wagner-Döbler, Email: iwd@gbf.de.

References

- Karr EA, Sattley WM, Jung DO, Madigan MT, Achenbach LA. Remarkable diversity of phototrophic purple bacteria in a permanently frozen Antarctic lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4910–4914. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4910-4914.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrahami S, Liesack W, Conrad R. Effects of temperature and fertilizer on activity and community structure of soil ammonia oxidizers. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:691–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Canstein H, Li Y, Timmis KN, Deckwer WD, Wagner-Dobler I. Removal of mercury from chloralkali electrolysis wastewater by a mercury-resistant Pseudomonas putida strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5279–5284. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5279-5284.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Döbler I, von Canstein H, Li Y, Timmis KN, Deckwer W-D. Removal of mercury from chemical wastewater by microorganisms in technical scale. Environ Sci Technol. 2000;34:4628–4634. [Google Scholar]

- Summers AO, Lewis E. Volatilization of mercuric chloride by mercury-resistant plasmid-bearing strains of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1973;113:1070–1072. doi: 10.1128/jb.113.2.1070-1072.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Camakaris J, Lee BT, Williams T, Morby AP, Parkhill J, Rouch DA. Bacterial resistances to mercury and copper. J Cell Biochem. 1991;46:106–114. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240460204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebert CA, Hall RM, Summers AO. Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:507–522. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.507-522.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G, Silver S. Bacterial resistance mechanisms for heavy metals of environmental concern. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;14:61–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01569887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Dobler I, Lunsdorf H, Lubbehusen T, von Canstein HF, Li Y. Structure and species composition of mercury-reducing biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4559–4563. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4559-4563.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Canstein H, Li Y, Leonhauser J, Haase E, Felske A, Deckwer WD, Wagner-Dobler I. Spatially oscillating activity and microbial succession of mercury-reducing biofilms in a technical-scale bioremediation system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1938–1946. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1938-1946.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Canstein H, Li Y, Wagner-Dobler I. Long-term performance of bioreactors cleaning mercury-contaminated wastewater and their response to temperature and mercury stress and mechanical perturbation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;74:212–219. doi: 10.1002/bit.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Canstein H, Kelly S, Li Y, Wagner-Dobler I. Species diversity improves the efficiency of mercury-reducing biofilms under changing environmental conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2829–2837. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2829-2837.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canstein HF, Li Y, Felske A, Wagner-Dobler I. Long-Term Stability of Mercury-Reducing Microbial Biofilm Communities Analyzed by 16S-23S rDNA Interspacer Region Polymorphism. Microb Ecol. 2001;42:624–634. doi: 10.1007/s00248-001-0028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn AM, Bruce KD, Strike P, Ritchie DA. Distribution, diversity and evolution of the bacterial mercury resistance (mer) operon. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;19:239–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkay T. Mercury Cycle. Encyclopedia of Microbiology. 2000;3:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fox B, Walsh CT. Mercuric reductase. Purification and characterization of a transposon-encoded flavoprotein containing an oxidation-reduction-active disulfide. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:2498–2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Canstein HF, Li Y, Felske A, Wagner-Dobler I. Long-term stability of mercury-reducing microbial biofilm communities analyzed by 16S-23S rDNA interspacer region polymorphism. Microb Ecol. 2001;42:624–634. doi: 10.1007/s00248-001-0028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes EA, Bale MJ, Cannon WH, J.M. Matsen. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by pyocyanin production on Tech agar. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;13:456–458. doi: 10.1128/jcm.13.3.456-458.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MC, Elliott GN, Osborn AM, Ritchie DA, Strike P. Diversity amongst Bacillus merA genes amplified from mercury resistant isolates and directly from mercury polluted soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;27:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brunke M, Deckwer WD, Frischmuth A, Horn JM, Lunsdorf H, Rhode M, Rohricht M, Timmis KN, Weppen P. Microbial retention of mercury from waste streams in a laboratory column containing merA gene bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;11:145–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felske A, Pauling BV, von Canstein HF, Li Y, Lauber J, Buer J, Wagner-Dobler I. Detection of small sequence differences using competitive PCR: molecular monitoring of genetically improved, mercury-reducing bacteria. Biotechniques. 2001;30:142–148. doi: 10.2144/01301rr02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitzel GM, Parsek MR. Heavy Metal Resistance of Biofilm and Planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:2313–2320. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.2313-2320.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penna VT, Martins SA, Mazzola PG. Identification of bacteria in drinking and purified water during the monitoring of a typical water purification system. BMC Public Health. 2002;2:13–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiby N, Krogh Johansen H., Moser C, Song Z, Ciofu O, Kharazmi A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the in vitro and in vivo biofilm mode of growth. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewzyk U, Szewzyk R, Manz W, Schleifer KH. Microbiological safety of drinking water. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:81–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher DG, Saunders NA, Owen RJ. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP -- Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti CJ, Dias Neto E, Simpson AJG. Rapid silver staining and recovery of PCR products separated on polyacrylamide gels. Biotechniques. 1994;17:915–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JM, Brunke M, Deckwer WD, Timmis KN. Pseudomonas-putida strains which constitutively overexpress mercury resistance for biodetoxification of organomercurial pollutants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:357–362. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.357-362.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]