Abstract

Studies show increased oxidative damage in the brains of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). To determine if RNA oxidation occurs in MCI, sections of hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus (HPG) from 5 MCI, 5 late stage AD (LAD) and 5 age-matched normal control (NC) subjects were subjected to immunohistochemistry using antibodies against 8-hydroxyguanine (8-OHG) and 1-N2-propanodeoxyguanosine (NPrG). Confocal microscopy showed 8-OHG and NPrG immunostaining was significantly (p < 0.05) elevated in MCI and LAD HPG compared with NC subjects and was predominately associated with neurons identified using the MC-1 antibody that recognizes conformational alterations of tau, which are associated with early neurofibrillary tangle formation. Pretreating sections with RNase or DNase-I showed immunostaining for both adducts was primarily associated with RNA. In addition, levels of both adducts in MCI were comparable to those measured in LAD, suggesting RNA oxidation may be an early event in the pathogenesis of neuron degeneration in AD.

Keywords: RNA, oxidative stress, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, lipid peroxidation

Introduction

An increasing body of evidence supports a role for oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Multiple studies over the past 10 to 15 years show increased lipid peroxidation, and protein, DNA, and RNA oxidation are present in multiple vulnerable regions of the late stage AD (LAD) brain (Markesbery and Lovell, 1998; Picklo et al., 2002; Nunomura et al., 2006; Sultana et al., 2006). Although these studies show oxidative damage is present in LAD, it is unclear whether oxidative damage is a consequence of the disease or whether it occurs early in the pathogenesis, thus making it a potential therapeutic target.

With recent emphasis on early diagnosis of adult dementing disorders, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a transition between normal aging and dementia, has become a research focus. Subjects with MCI convert to AD or other dementias at a rate of 10% to 15% per year (Knopman et al., 2003), although approximately 5% remain stable or correct back to normal (Bennett et al., 2002; DeCarli, 2003). Recent studies of MCI brain show increased levels of DNA (Wang et al., 2006) and protein oxidation (Sultana et al., 2006) and lipid peroxidation (Keller et al., 2005; Markesbery et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2006) compared to age-matched normal control (NC) subjects. These studies also show levels of oxidative damage in MCI that are comparable to those observed in LAD, suggesting oxidative damage to a variety of cellular targets occurs early in the progression of AD and may contribute to the pathogenesis of neuron degeneration.

Although previous studies show increased levels of RNA oxidation in LAD (Nunomura et al., 1999; Nunomura et al., 2001; Ding et al., 2005; Ding et al., 2006; Shan and Lin, 2006) and familial AD (Nunomura et al., 2004) as well as other neurologic disorders including Parkinson’s disease (Zhang et al., 1999) and diffuse Lewy body disease (DLB) (Nunomura et al., 2002), there have been few studies of RNA oxidation in MCI. Because RNA oxidation may lead to alterations in protein synthesis, its presence early in the progression of AD could contribute to changes in protein translation observed in AD. To determine whether RNA oxidative modification occurs in vulnerable neurons in MCI, we used immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy to analyze sections of hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus (HPG) double labeled for MC-1, an antibody that recognizes specific conformational changes in tau observed only in AD (Weaver et al., 2000) and antibodies against 8-hydroxyguanine (8-OHG), a by-product of hydroxyl attack of C-8 of guanine or 1,N2-propanoguanosine (NPrG), an adduct formed between guanine and acrolein, anα,β-unsaturated aldehydic by-product of lipid peroxidation elevated in MCI and LAD brain (Lovell et al., 2001; Williams et al., 2006).

Materials and methods

Subject selection and neuropathologic examination

Sections (10 μm) of paraffin embedded HPG were obtained from short postmortem interval (PMI) autopsies of 5 subjects with LAD (3 men, 2 women), 5 subjects with MCI (2 men, 3 women) and 5 age-matched normal control (NC) subjects (2 men, 3 women) through the Neuropathology Core of the University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UK-ADC). All LAD subjects had annual mental status testing and physical and neurological examinations, demonstrated progressive intellectual decline, and met NINCDS-ADRDA Workgroup criteria for the clinical diagnosis of probable AD (McKhann et al., 1984).

Control subjects were followed longitudinally in the normal control clinic of the UK-ADC and had neuropsychologic testing annually and physical examinations biannually. All control subjects had neuropsychologic scores in the normal range and showed no evidence of memory decline. Subjects with MCI were derived from the control group and were followed longitudinally in the UK-ADC clinic. All MCI patients were normal on enrollment into the longitudinal study and developed MCI during follow-up. The clinical criteria for diagnosis of amnestic MCI were those of Petersen et al. (Petersen et al., 1999) and included: a) memory complaints, b) abnormal memory impairment for age and education, c) normal general cognitive function, d) intact activities of daily living, and e) the subject did not meet criteria for dementia. Objective memory test impairment was based on a score of ≤ 1.5 standard deviations from the mean of controls on the CERAD Word List Learning Task (Morris et al., 1989) and corroborated in some cases with the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

Histopathologic examination of multiple sections of neocortex, hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, amygdala, basal ganglia, thalamus, nucleus basalis of Meynert, midbrain, pons, medulla, and cerebellum using hematoxylin and eosin and the modified Bielschowsky stains along with 10D-5 (for Aβ) and α-synuclein immunochemistry were carried out on all subjects. All AD patients met accepted criteria for the histopathologic diagnosis of AD (Mirra et al., 1991) (National, 1997), and typically demonstrated Braak scores of VI.

Histopathologic examination of control subjects showed only age-associated changes and Braak staging scores of I to II. Control subjects met the NIA-Reagan Institute low likelihood criteria for the histopathologic diagnosis of AD. MCI subjects demonstrated only age-associated brain gross changes. Braak staging scores were II to V. The major difference between NC subjects and MCI patients was a significant increase in neuritic plaques in neocortical regions and an increase in neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in amygdala, hippocampus, and entorhinal cortex (Markesbery et al., 2006). Demographic data for all subjects in the study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Mean ± SEM Age (yr) | Sex | Mean ± SEM PMI (hr) | Median Braak Staging Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 87.2 ± 1.1 | 2 Men/ 3 Women | 11.4 ± 8.7 | I |

| MCI | 87.4 ± 1.5 | 2 Men/ 3 Women | 4.9 ± 1.8 | III* |

| LAD | 86.2 ± 1.8 | 3 Men/ 2 Women | 5.6 ± 3.0 | VI* |

Immunohistochemistry and antibodies

To visualize the cellular distribution of RNA oxidation, sections (10 μm) of paraffin-embedded HPG from MCI, LAD and NC subjects were cut using a Shandon Finesse microtome (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), placed on Plus-slides and rehydrated through xylene, descending alcohols, and water. Following rehydration sections were digested with 10 μg/ml proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 40 min at 37° C. Sections were double-labeled for confocal microscopy using antibodies against 8-OHG or NPrG and MC-1, a conformation-dependent monoclonal antibody that recognizes distinct pathologic confirmations of tau (Jicha et al., 1997) observed only in AD brain (Weaver et al., 2000) that identifies early NFT formation (Weaver et al., 2000) (kindly provided by Dr. Peter Davies). For immunohistochemistry sections were blocked in 10% normal goat serum in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 150 mM tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) at room temperature for 2 h. For NPrG and MC-1 double labeling, sections were incubated overnight in a 1:100 dilution of MC-1 and a 1:100 dilution of a custom polyclonal antibody generated against synthetic NPrG prepared as previously described (Chung et al., 1984) in 1.5% normal goat serum/TBS at 4° C. Following thorough washing in TBS, sections were incubated in a 1:1000 dilution of Alexa-568 conjugated anti-mouse IgG and 1:1000 dilution of Alexa-488 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 2 h at room temperature. For 8-OHG/MC-1 double labeling, sections were sequentially stained with MC-1 primary antibody and Alexa-568 labeled secondary as described above, blocked in 10% normal goat serum/TBS and incubated overnight in a 1:100 dilution of anti-8-OHG antibody (QED Biosciences, San Diego, CA) in 1.5% goat serum/TBS. Following thorough rinsing in TBS sections were incubated in a 1:1000 dilution of Alexa-488 conjugated IgG/1.5% goat serum/TBS for 2 h at room temperature. After 5 rinses in TBS and distilled/deionized water, sections were coverslipped using fluorescent anti-fade (Molecular Probes) and imaged using a Leica DM IRBE confocal microscope equipped with argon, krypton and HeNe lasers and a 40X oil objective. Confocal images were captured from a single z plane without optical sectioning and were the average of 3 scans. Images were captured from 10 fields/section with an average of 10 to 20 cells per field without knowledge of subject diagnosis. Fluorescence intensities of all cells in each field were quantified using Leica image analysis software. Mean fluorescence intensities were calculated for 8-OHG or NPrG for each slide.

To verify specificity of RNA staining, representative sections were pretreated with RNase free DNase-I (10 U/μl in PBS, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) or DNase-I free RNase (0.5 μg/μl PBS, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) for 2 h at 37° C following proteinase-K treatment. To verify antibody specificity, antibodies were preincubated with 1 mg/ml 8-OHG (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) or NPrG prepared as previously described (Chung et al., 1984) at 4° C for 16 hr prior to addition to sections.

To verify RNA oxidative modifications were associated with neurons and not astrocytes, representative sections of HPG were triple labeled for 8-OHG or NPrG, neuron specific β-tubulin(β-tubulin-III; Tuj-1), and GFAP, an astrocyte specific marker. The sections were labeled for 8-OHG or NPrG as described above, blocked 1 h in 10% normal goat sereum/TBS followed by incubation overnight in a 1:100 dilution of monoclonal anti-tubulin-III (Tuj-1; Covance, Denver, PA ) and a 1:100 dilution of rabbit anti-GFAP (Dako, Capinteria, CA). The sections were washed three times in TBS and incubated in 10% normal goat serum/TBS containing Alexa-568 labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000) and Alexa-633 labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000) for 1 h. Following three washes in TBS the sections were coverslipped using fluorescent anti-fade and imaged as described above using a 100X objective.

Statistical analysis

Age and postmortem intervals (PMI) were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and ABSTAT software (AndersonBell, Arvada, CO). Results of 8-OHG and NPrG immunostaining are reported as mean ± SEM% control immunostaining and were compared using ANOVA. Braak staging scores were compared using non-parametric testing and the Mann-Whitney U-test and results are expressed as the median.

Results

Subject demographic data are shown in Table 1. Statistical comparison of age, PMI, and Braak scores showed no significant differences in age or PMI between control, MCI or LAD subjects. Braak staging scores for MCI (median = III) and LAD subjects (median = VI) were significantly higher than for NC subjects (median = I).

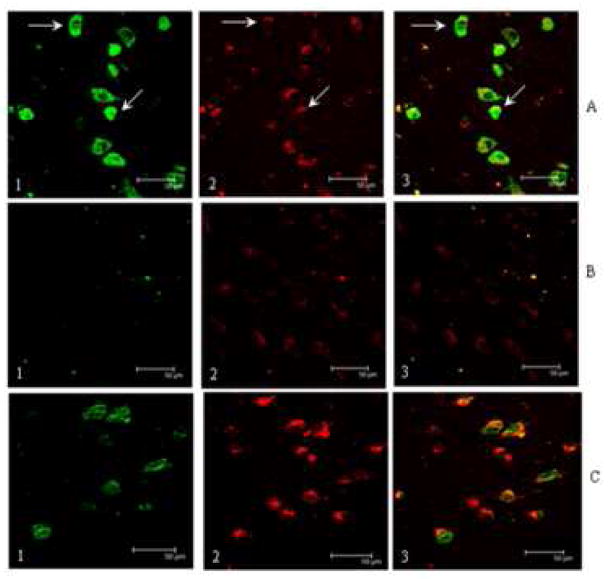

Figure 1 shows representative confocal micrographs of HPG immunostained for NPrG (1-A1; green) or 8-OHG (1-B1; green), neuron specific β-tubulin-III (Banerjee et al., 1990) (Tuj-1; 1-A2, 1-B2; blue) and GFAP, an astrocyte specific marker (1-A3, 1-B3; red). The last image in each series is a merged image. Immunostaining for NPrG was primarily associated with Tuj-1-positive neurons (1-A2) and not GFAP-positive astrocytes (1-A3). Consistent with previous studies (Nunomura et al., 1999), Figure 1-B shows 8-OHG immunostaining (1-B1; green) is specifically associated with Tuj-1-positive neurons (1-B2; blue) and not is not associated with GFAP-positive astrocytes (1-B3; red).

Fig. 1.

Confocal micrographs (100X objective) of representative sections of HPG immunostained for 1-N2-propanoguanosine, an exocyclic adduct formed between guanosine and acrolein, anα, β unsaturated aldehydic by-product of lipid peroxidation (1-A1), Tuj-1, a monoclonal antibody against neuron specific tubulin-III (Tuj-1; 1-A2; blue) and GFAP, an astrocyte specific marker (1-A3; red). Figure 1-A4 is a merged image. Note NPrG immunostaining is uniquely associated with β-tubulin-III-1-positive neurons and is minimally associated with GFAP-positive astrocytes. Figure 1-B shows an adjacent section of HPG immunostained for 8-OHG (1-B1; green), Tuj-1 (1-B2; blue) and GFAP (1-B3; red). Figure 1-B4 is a merged image. As was observed for NPrG, immunostaining for 8-OHG was specifically associated with Tuj-1-positive neurons and not with GFAP-positive astrocytes. Scale bar = 20 μm.

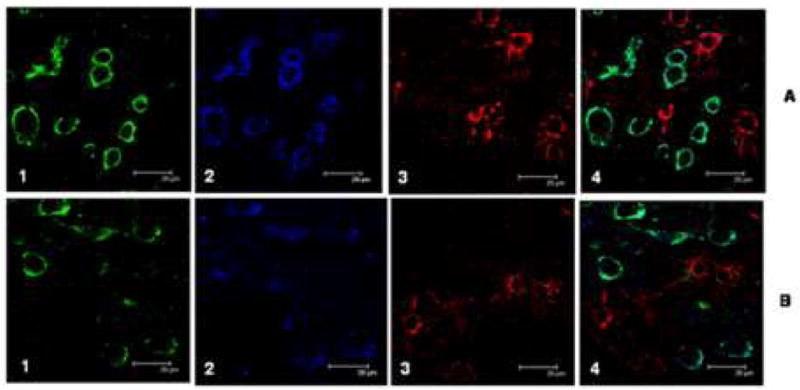

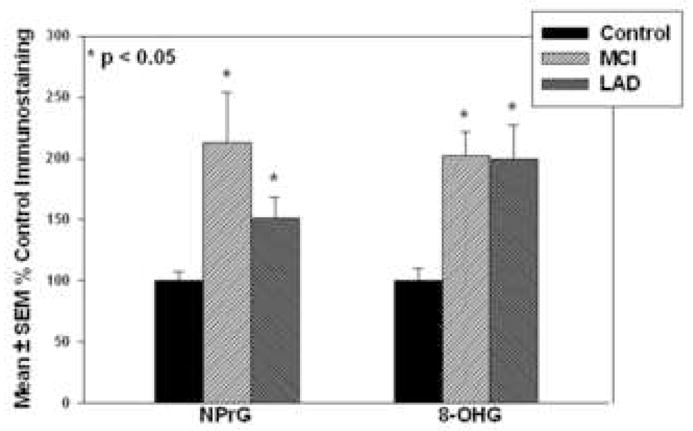

Figure 2 shows representative confocal micrographs of MCI HPG immunostained for NPrG (2-A1; green) and MC-1 (2-A2; red). The third panel shows a merged image. In general, NPrG immunostaining was present in MC-1 positive neurons throughout CA1, subiculum and the parahippocampal gyrus of MCI and LAD HPG. Immunostained neurons were typically flame-shaped, globular and hemispiked. Immunostaining for NPrG was generally stronger in MC-1 positive neurons compared to MC-1 negative neurons and was predominantly cytoplasmic. Figure 2-A shows there was considerable overlap between MC-1 and NPrG immunostaining (arrows) although we did observe neurons immunopositive for NPrG but MC-1 negative (arrows). The observation of increased NPrG immunostaining in neurons that show minimal MC-1 immunostaining suggests RNA oxidation preceeds the earliest changes in tau conformation and may play a meaningful role in neurodegeneration and NFT formation in AD. Figure 2-B shows a representative section of MCI HPG immunostained using NPrG antibody pre-incubated with 1-N2-propanoguanine for 16 hr prior to addition to the section and shows nearly complete elimination of NPrG immunostaining (2-B1) but not MC-1 immunostaining (2-B2). Figure 2-C shows an adjacent section pretreated with DNase-I-free RNase prior to immunostaining and shows decreased NPrG immunostaining (2-C1) but no change in MC-1 staining (2-C2). Statistical comparison of NPrG immunostaining (Figure 3) showed significantly (p < 0.05) increased fluorescence intensity of neurons in both MCI (213.0 ± 40.8% control) and LAD (150.9 ± 17.7% control) compared to NC subjects (100.0 ± 7.4%). There was no significant difference in NPrG immunostaining between MCI and LAD subjects.

Fig. 2.

Confocal micrographs of representative sections of MCI HPG immunostained for 1-N2-propanoguanosine (2-A1) and MC-1 (2-A2), an antibody that recognizes conformational changes in tau associated with early neurofibrillary tangle formation. Figure 2-A3 shows a merged image. Note NPrG immunostaining is associated with MC-1 positive neurons although we did observe pronounced NPrG immunostaining in several neurons with minimal MC-1 staining (arrows) suggesting oxidative damage to RNA may precede changes in tau conformation. Confocal images in 2-B show a representative section of MCI HPG pretreated with DNase-I-free RNase prior to immunostaining with MC-1 and NPrG. RNase treatment eliminated NPrG staining (2-B1) but not MC-1 staining (2-B2). Figure 2-C shows preincubation of the NPrG antibody with NPrG diminished immunostaining for the acrolein/guanine adduct (2-C1) but did not inhibit MC-1 staining (2-C2). The scale bar in all images = 50 μm.

Fig. 3.

Mean ± SEM fluorescence intensities for NPrG and 8-OHG immunostaining. * p < 0.05.

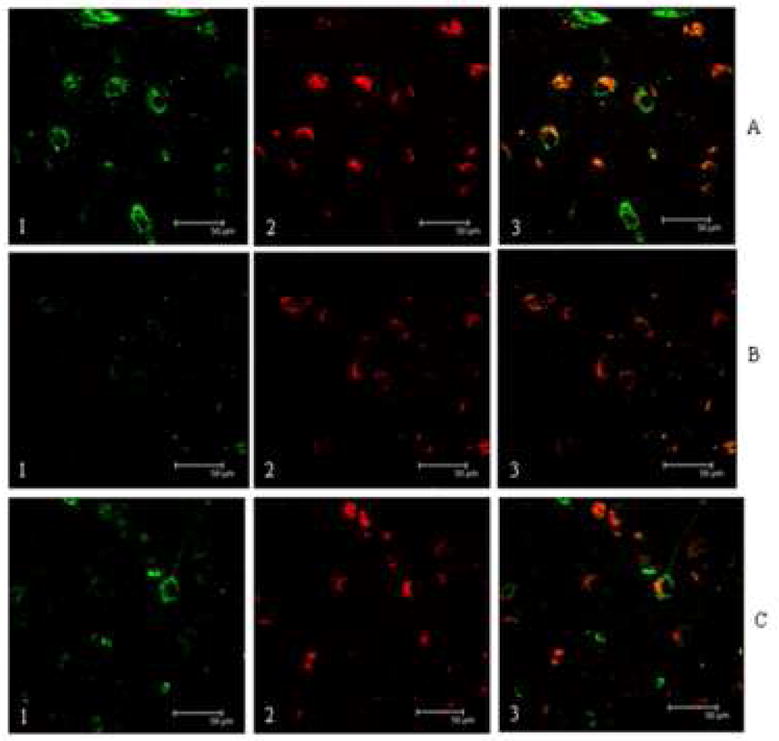

Double immunolabeling of MCI and LAD HPG with MC-1 and an antibody against 8-OHG showed similar results to those observed using anti-NPrG. Figure 4-A shows a representative section of MCI HPG immunostained for 8-OHG and MC-1 and shows considerable overlap between 8-OHG (panel 1; green) and MC-1 (panel 2; red). Panel 3 of each series shows a merged image of panels 1 and 2. As was observed for NPrG, 8-OHG immunostaining was present in several neurons that showed minimal or no MC-1 immunostaining suggesting RNA oxidation occurs prior to changes in tau conformation and may contribute to neurodegeneration and NFT formation. Figure 4-B shows an adjacent section immunostained using 8-OHG antibody that had been preincubated with 1 mg/ml 8-hydroxyguanine for 16 hr prior to addition to the section and shows diminished 8-OHG immunostaining (4-B1) but no change in MC-1 immunostaining (4-B2). As observed for NPrG immunostaining, pretreatment of the section with DNase-I-free RNase prior to immunohistochemistry significantly decreased 8-OHG immunostaining (Figure 4-C1) but not MC-1 immunostaining (4-C2). Statistical comparison of fluorescence intensity of neurons immunopositive for 8-OHG showed a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase in MCI (202.5 ± 19.5% control) and LAD (200.0 ± 27.2% control) compared to NC (100.0 ± 10.1%) subjects (Figure 3). Statistical comparison of fluorescence intensities for 8-OHG immunostaining between MCI and LAD HPG showed no significant difference.

Fig. 4.

Confocal micrographs of representative sections of MCI HPG immunostained for 8-OHG (1) and MC-1 (2). Panel 3 shows a merged image. Figure 4-A1 shows 8-OHG immunostaining is present in neurons immuopositive for MC-1 (4-A2). Confocal images in Figure 4-B show a representative section of MCI HPG pretreated with DNase-I-free RNase prior to immunostaining with MC-1 and 8-OHG. RNase treatment essentially eliminated 8-OHG staining (4-B1) but not MC-1 staining (4-B2). Figure 4-C shows preincubation of the 8-OHG antibody with 8-hydroxyguanosine diminished immunostaining for the acrolein/guanosine adduct (4-C1) but did not inhibit MC-1 staining (4-C2). The scale bar in all images = 50 μm.

Discussion

Considerable evidence shows oxidative damage to a variety of macromolecules can cause cellular dysfunction and lead to cell death. Numerous recent studies support a role for oxidative damage of proteins, lipids, DNA, and RNA in the pathogenesis of AD, although it has been unclear whether the damage is a secondary event or a primary cause of neurodegeneration in AD. With the recent characterization of MCI as an early clinical manifestation of AD, studies have been carried out to determine if oxidative damage is present at the early states of the disease.

Because of the brain’s high lipid content there is increased likelihood of attack of polyunsaturated fatty acids by reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydroxyl radical, leading to lipid peroxidation. Attack of polyunsaturated fatty acids by ROS can lead to structural damage to membranes and production of a variety of saturated and unsaturated aldehydic byproducts including theα, β-unsaturated aldehydes acrolein and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE). These secondary products of lipid peroxidation are neurotoxic and can lead to further cell death at sites remote from the original peroxidation. Previous studies of lipid peroxidation in LAD brain show significantly elevated levels of acrolein and HNE in vulnerable brain regions compared to NC subjects (Markesbery and Lovell, 1998). Immunohistochemical studies also show elevated HNE and acrolein in AD brain associated with NFT-bearing neurons (Montine et al., 1997; Calingasan et al., 1999). Because of the reactivity of HNE and acrolein, they quickly react with proteins, DNA or RNA. Reaction of acrolein with guanine in DNA or RNA leads to the formation of NPrG,, a bulky exocyclic adduct shown to be significantly elevated in DNA isolated from HPG but not superior and middle temporal gyri or cerebellum from LAD subjects compared to NC subjects (Liu et al., 2005). The present study is the first to demonstrate a significant elevation of NPrG in RNA in MCI and LAD brain that is associated with degenerating neurons.

In addition to lipid peroxidation, ROS can directly attack RNA leading to oxidative base modification. Although RNA has generally been thought to undergo rapid turnover that diminishes accumulation of oxidative damage, recent studies (Shan et al., 2003; Ding et al., 2006; Shan and Lin, 2006) suggest RNA accumulates significant levels of oxidative damage. Degradation of RNA, particularly mRNA, is essential for regulation of gene expression and is often initiated by endogenous or exogenous signals by a gradual shortening of the poly (A) tail (Beelman and Parker, 1995; van Hoof and Parker, 1999; Tucker and Parker, 2000; Mitchell and Tollervey, 2001). Following poly A shortening, recent data suggest mRNA degradation occurs through action of a complex of endosomal proteins (van Hoof and Parker, 2002). Although genes for components of the endosomal complex have been identified in yeast and are highly conserved among eukaryotes, it is unclear if they are involved in the degradation of mRNA in humans.

The oxidation of RNA might contribute specific modifications including introduction of strand breaks (Rinke and Brimacombe, 1978; Singh et al., 2004); RNA crosslinking; and specific base modifications such as thymine glycol, 8-OHG, and hydroxymethyluracil (Jezowska-Bojczuk et al., 2002; Martinet et al., 2004). Consistent with our current data, Smith and Perry and colleagues demonstrated increased neuronal RNA oxidation in LAD (Nunomura et al., 1999; Nunomura et al., 2004), dementia with Lewy bodies (Nunomura et al., 2002), and Parkinson’s disease (Zhang et al., 1999). Using immunohistochemistry, these studies show that the oxidative changes occur primarily in the cytoplasm of vulnerable neurons in these disorders. In more recent studies, Shan et al. (Shan et al., 2003) identified several oxidized mRNA species in the brain in LAD that when expressed in cell lines led to abnormal processing of multiple proteins. In further studies, Shan and Lin (Shan and Lin, 2006) showed 30% to 70% of mRNAs in the LAD frontal cortex were oxidized. Quantitative analysis showed the relative amounts of oxidized transcripts reach 50% to 70% for some RNA species. In addition, another study identified that rRNA and mRNA are oxidized by redox-active iron in LAD (Honda et al., 2005), although all of the oxidized mRNA was isolated from a single AD patient. The evaluation was based on amplification abundance compared with the lowest abundance isolated gene from the same group, instead of related genes from controls. This raises the question about the representative significance of these genes, which might be oxidized in controls as well. However, these published findings have implications for AD pathogenesis.

Although several studies show significant RNA oxidative modification (8-OHG) in LAD, it is unclear whether the damage is a secondary product or a primary cause of neurodegeneration in AD. With the recent characterization of MCI as the earliest clinical manifestation of AD studies have been carried out to determine if oxidative damage is present in subjects early in disease progression. Studies by Keller et. al. (Keller et al., 2005) showed significantly increased protein carbonyl formation and increased levels of lipid peroxidation measured using the thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARs) assay in temporal lobe of MCI subjects compared to NC subjects. In addition, Markesbery et al. (Markesbery et al., 2005) showed significantly elevated levels of F2-isoprostanes and F4-neuroprostanes in multiple vulnerable regions of MCI brain compared to NC subjects. Using LC/MS, Williams et al. (Williams et al., 2006) showed significantly elevated levels of HNE and acrolein in the HPG and superior and middle temporal gyri of MCI subjects compared to NC subjects.

Studies of oxidative damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in MCI show significant elevations of 8-OHG, 8-OHA, and 5-hydroxycytosine in neocortical regions of MCI brain compared to NC subjects (Wang et al., 2006). In the only study of oxidative RNA damage in early AD, Ding et al. (Ding et al., 2006) showed significantly elevated 8-OHG immunoreactivity in the inferior parietal lobule of subjects early in disease progression. In the first immunohistochemical characterization of RNA oxidative modification in MCI, our current data show statistically significantly elevations of 8-OHG in RNA from neurons showing early changes in tau conformation associated with AD in HPG from MCI subjects compared to HPG from NC subjects. Although our previous studies show elevated 8-OHG in MCI DNA our current study demonstrates elevations of 8-OHG immunostaining in neurons treated with RNase free DNase-I but not in sections pretreated with DNase-I free RNase suggesting that the 8-OHG levels measured in this study are associated with RNA. In addition our current data also show a significant elevation of levels of NPrG in RNA from MCI subjects associated with MC-1 positive neurons. Although our previous study showed elevated NPrG in DNA in LAD, there have been no studies of levels of this exocyclic adduct in RNA in MCI.

Conclusions

Overall, our data show elevated RNA oxidative modification in neurons undergoing early NFT formation in the HPG of MCI and LAD subjects. Consistent with previous studies of lipid, protein and DNA oxidation, levels of RNA oxidative damage in MCI are comparable to those observed in LAD, suggesting that oxidative damage is an early event in the pathogenesis of AD. The presence of RNA oxidative modification early in the progression of AD could contribute to alterations of protein processing and contribute to neuron degeneration.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants 5-P01-AG05119 and 1P30-AG028383, and by a grant from the Abercrombie Foundation. The authors thank Ms. Paula Thomason for technical and editorial assistance, Ms. Sonya Anderson for subject demographic data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Banerjee A, Roach MC, Trcka P, Luduena RF. Increased microtubule assembly in bovine brain tubulin lacking the type III isotype of beta-tubulin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1794–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beelman CA, Parker R. Degradation of mRNA in eukaryotes. Cell. 1995;81:179–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Beckett LA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Fox JH, Bach J. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calingasan NY, Uchida K, Gibson GE. Protein-bound acrolein: a novel marker of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1999;72:751–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung FL, Young R, Hecht SS. Formation of cyclic 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts in DNA upon reaction with acrolein or crotonaldehyde. Cancer Res. 1984;44:990–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarli C. Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Markesbery WR, Cecarini V, Keller JN. Decreased RNA, and increased RNA oxidation, in ribosomes from early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:705–10. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Markesbery WR, Chen Q, Li F, Keller JN. Ribosome dysfunction is an early event in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9171–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3040-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Smith MA, Zhu X, Baus D, Merrick WC, Tartakoff AM, Hattier T, Harris PL, Siedlak SL, Fujioka H, Liu Q, Moreira PI, Miller FP, Nunomura A, Shimohama S, Perry G. Ribosomal RNA in Alzheimer disease is oxidized by bound redox-active iron. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20978–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezowska-Bojczuk M, Szczepanik W, Lesniak W, Ciesiolka J, Wrzesinski J, Bal W. DNA and RNA damage by Cu(II)-amikacin complex. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5547–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jicha GA, Bowser R, Kazam IG, Davies P. Alz-50 and MC1, a new monoclonal antibody raised to paired helical filaments, recognize conformational epitopes on recombinant tau. J Neurosci Res. 1997;48:128–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970415)48:2<128::aid-jnr5>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JN, Schmitt FA, Scheff SW, Ding Q, Chen Q, Butterfield DA, Markesbery WR. Evidence of increased oxidative damage in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2005;64:1152–6. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156156.13641.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Dickson DW, Johnson KA, Petersen LE, McDonald WC, Braak H, Petersen RC. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1087–95. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Lovell MA, Lynn BC. Development of a method for quantification of acrolein-deoxyguanosine adducts in DNA using isotope dilution-capillary LC/MS/MS and its application to human brain tissue. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5982–9. doi: 10.1021/ac050624t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell MA, Xie C, Markesbery WR. Acrolein is increased in Alzheimer’s disease brain and is toxic to primary hippocampal cultures. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:187–94. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markesbery WR, Kryscio RJ, Lovell MA, Morrow JD. Lipid peroxidation is an early event in the brain in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:730–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Four-hydroxynonenal, a product of lipid peroxidation, is increased in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:33–6. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markesbery WR, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Davis DG, Smith CD, Wekstein DR. Neuropathologic substrate of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:38–46. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinet W, de Meyer GR, Herman AG, Kockx MM. Reactive oxygen species induce RNA damage in human atherosclerosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:323–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–86. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P, Tollervey D. mRNA turnover. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:320–5. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine KS, Olson SJ, Amarnath V, Whetsell WO, Jr, Graham DG, Montine TJ. Immunohistochemical detection of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal adducts in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with inheritance of APOE4. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:437–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Mellits ED, Clark C. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–65. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(S4):S1–S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Chiba S, Kosaka K, Takeda A, Castellani RJ, Smith MA, Perry G. Neuronal RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroreport. 2002;13:2035–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200211150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Chiba S, Lippa CF, Cras P, Kalaria RN, Takeda A, Honda K, Smith MA, Perry G. Neuronal RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of familial Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Honda K, Takeda A, Hirai K, Zhu X, Smith MA, Perry G. Oxidative damage to RNA in neurodegenerative diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:82323. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/82323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Perry G, Aliev G, Hirai K, Takeda A, Balraj EK, Jones PK, Ghanbari H, Wataya T, Shimohama S, Chiba S, Atwood CS, Petersen RB, Smith MA. Oxidative damage is the earliest event in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:759–67. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.8.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Perry G, Hirai K, Aliev G, Takeda A, Chiba S, Smith MA. Neuronal RNA oxidation in Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;893:362–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picklo MJ, Montine TJ, Amarnath V, Neely MD. Carbonyl toxicology and Alzheimer’s disease. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002;184:187–97. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinke J, Brimacombe R. 30S ribosomal proteins cross-linked to 16S RNA by periodate oxidation followed by borohydride reduction. Mol Biol Rep. 1978;4:153–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00777516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan X, Lin CL. Quantification of oxidized RNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:657–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan X, Tashiro H, Lin CL. The identification and characterization of oxidized RNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4913–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04913.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Dwarakanath BS, Mathew TL. DNA ligand Hoechst-33342 enhances UV induced cytotoxicity in human glioma cell lines. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2004;77:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana R, Perluigi M, Butterfield DA. Protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation in brain of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease: insights into mechanism of neurodegeneration from redox proteomics. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:2021–37. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M, Parker R. Mechanisms and control of mRNA decapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:571–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof A, Parker R. The exosome: a proteasome for RNA? Cell. 1999;99:347–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof A, Parker R. Messenger RNA degradation: beginning at the end. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R285–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in mild cognitive impairment. J Neurochem. 2006;96:825–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:719–27. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TI, Lynn BC, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased levels of 4-hydroxynonenal and acrolein, neurotoxic markers of lipid peroxidation, in the brain in Mild Cognitive Impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1094–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Perry G, Smith MA, Robertson D, Olson SJ, Graham DG, Montine TJ. Parkinson’s disease is associated with oxidative damage to cytoplasmic DNA and RNA in substantia nigra neurons. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1423–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]