SUMMARY

Small Cajal body (CB)-specific RNPs (scaRNPs) function in posttranscriptional modification of small nuclear (sn)RNAs. An RNA element, the CAB box, facilitates CB localization of H/ACA scaRNPs. Using a related element in Drosophila C/D scaRNAs, we purified a fly WD40 repeat protein that UV crosslinks to RNA in a C/D CAB box dependent manner and associates with C/D and mixed domain C/D-H/ACA scaRNAs. Its human homolog, WDR79, associates with C/D, H/ACA, and mixed domain scaRNAs, as well as with telomerase RNA. WDR79’s binding to human H/ACA and mixed domain scaRNAs is CAB box dependent and its association with mixed domain RNAs also requires the ACA motif, arguing for additional interactions of WDR79 with H/ACA core proteins. We demonstrate a requirement for WDR79 binding in the CB localization of a scaRNA. This and other recent reports establish WDR79 as a central player in the localization and processing of nuclear RNPs.

INTRODUCTION

Stable RNAs in eukaryotic cells undergo extensive posttranscriptional modification. The most abundant modifications in ribosomal (r)RNA and small nuclear (sn)RNAs are 2′-O-methylation of certain sugar moieties and conversion of selected uridines to pseudouridines (reviewed in Maden, 1990; Massenet et al., 1998). Both types of modifications in rRNA are carried out in nucleoli by small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins (snoRNPs), while the modifications in snRNAs are introduced in Cajal bodies (CBs) by highly related particles referred to as Cajal body-specific RNPs or scaRNPs (reviewed in (Carmo-Fonseca, 2002; Terns and Terns, 2002). The box C/D RNPs are responsible for 2′-O-methylation, while the H/ACA RNPs carry out pseudouridylation.

Knowledge of the composition, structure, and function of the modification RNPs comes primarily from analyses of snoRNPs. Each snoRNP particle contains a unique small RNA molecule and a common set of four core proteins. Accordingly, a C/D particle possesses a box C/D RNA, typically of 70–90 nt, and the fibrillarin (the methyltransferase), Nop58, Nop56, and 15.5 kD proteins (reviewed in (Reichow et al., 2007). An H/ACA snoRNP is composed of a 120–200 nt-long box H/ACA snoRNA and the NAP57/dyskerin (the pseudouridine synthase), GAR1, NHP2, and NOP10 proteins (reviewed in Meier, 2006; Reichow et al., 2007; Terns and Terns, 2006). ScaRNP particles are similar but more complex, particularly in vertebrates where they often consist of two snoRNP domains. Such composite particles possess either one box C/D and one H/ACA (C/D-H/ACA scaRNPs) (Darzacq et al., 2002; Jady and Kiss, 2001), two box C/D (Tycowski et al., 2004), or two box H/ACA domains (Kiss et al., 2004; Kiss et al., 2002). Except for U85, which is a C/D-H/ACA scaRNP in both vertebrate and Drosophila cells (Jady and Kiss, 2001), all known invertebrate scaRNPs are predicted to be single-domain particles (Huang et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2005a; Yuan et al., 2003).

CBs are dynamic nuclear foci found in most eukaryotic cells (reviewed in Cioce and Lamond, 2005). Their size and number vary between different cell types and metabolic states. CBs are involved in the biogenesis and function of nuclear RNP particles, such as spliceosomal snRNPs, snoRNPs, and telomerase RNP, which accumulate only transiently in CBs (reviewed in Kiss et al., 2006; Matera and Shpargel, 2006; Stanek and Neugebauer, 2006). In vertebrates, CBs also harbor the U7 snRNP and frequently associate with histone gene loci; thus, they have been linked to histone mRNA 3′ end processing (reviewed in Dominski and Marzluff, 2007). Recently, CBs have been identified in Drosophila (Liu et al., 2006). Fly CBs also harbor components of the snRNP maturation machinery, but do not accumulate the U7 snRNP, which instead is found in distinct nuclear structures called histone locus bodies, or HLBs (Liu et al., 2006). Plant CBs, in addition to their role in snRNP assembly, have been postulated to be centers for 24-nt siRNA processing and the assembly of the effector complex for RNA-dependent DNA methylation (reviewed in Pontes and Pikaard, 2008).

The role of CBs in snRNA modification and snRNP assembly has been a subject of intense study (reviewed in Patel and Bellini, 2008; Stanek and Neugebauer, 2006). The RNA polII-transcribed snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, and U5), after re-import from the cytoplasm, where they acquire the Sm core proteins and the TMG cap, accumulate transiently in CBs. Here, they are subject to extensive 2′-O-methylation and pseudouridylation (Jady et al., 2003); these modifications trigger further assembly with specific proteins (Nesic et al., 2004; Yu et al., 1998). Accordingly, the RNP particles that carry out the snRNA modification, the scaRNPs, are also found in CBs.

Previously, Richard et al. (2003) demonstrated that a 4 nt-long RNA element called the CAB box, which is present in both apical loops of the H/ACA domain, is essential for the CB localization of human U85 C/D-H/ACA scaRNA. The CAB tetranucleotide can be recognized in the majority, if not all, of H/ACA and mixed domain C/D-H/ACA scaRNAs from both metazoan and plant cells (Kiss et al., 2006; Richard et al., 2003). It is also present in the H/ACA domain of vertebrate telomerase RNA (Jady et al., 2004). Alignment of more than 200 vertebrate CAB boxes revealed the consensus ugAG, with the AG dinucleotide being highly conserved and essential for the localization of scaRNAs to CBs (Kiss et al., 2006; Richard et al., 2003; Theimer et al., 2007). However, the CB localization signal(s) on C/D scaRNPs, as well as the trans-acting factors that localize scaRNPs to CBs have remained elusive.

Here, we identify in Drosophila C/D scaRNAs an RNA element related to but considerably different from the H/ACA scaRNA CAB box. Short RNAs carrying this element UV crosslink to a 70 kD Drosophila protein. Using the UV crosslinking assay and RNA affinity chromatography, we purified and identified the 70 kD species as a conserved WD40 protein, termed WDR79 in human (Consortium, 2004). We demonstrate that this protein binds cellular scaRNAs in a CAB box dependent manner and that this interaction is required for the scaRNAs to accumulate in CBs.

RESULTS

Identification of a CAB-like Sequence in Drosophila C/D scaRNAs

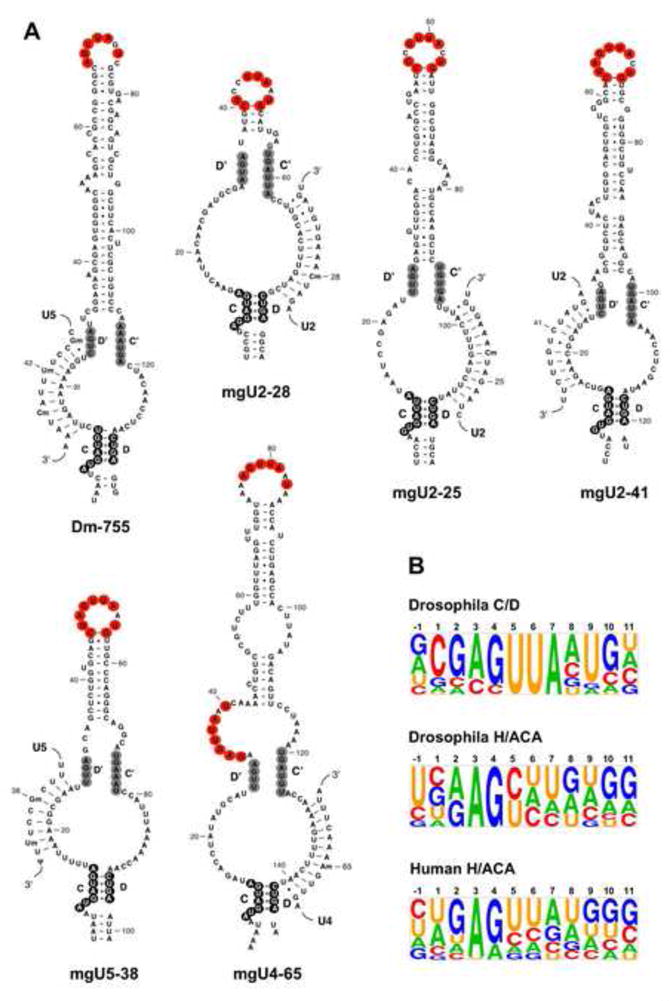

We searched for conserved sequence and/or secondary structure elements that might constitute a CB localization signal for box C/D scaRNAs in Drosophila. Two previously identified box C/D guide RNAs predicted to modify D. melanogaster snRNAs, Dm-755 (Yuan et al., 2003) and mgU2-28 (Huang et al., 2005b), exhibit single-domain guide RNA structures, thus simplifying the search (Figure 1A). Using bioinformatics, we identified four additional single-domain box C/D guide RNAs in multiple Drosophila species. Since they are predicted to modify U2, U4, or U5 snRNA, we refer to them as mgU2-25, mgU2-41, mgU4-65, and mgU5-38 RNAs (see Figure 1A and data not shown). Yet another Drosophila guide for modification of snRNAs, the mixed domain C/D-H/ACA U85 scaRNA, was earlier documented to localize to CBs (Liu et al., 2006; Richard et al., 2003). This argues that the box C/D RNAs likewise can be referred to as scaRNAs. Northern blot analyses confirmed the expression of mgU2-25, mgU2-41, mgU4-65, and mgU5-38 scaRNAs in S2 tissue culture cells (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

A CAB-like box in D. melanogaster box C/D scaRNAs. (A) Primary and predicted secondary structures of previously reported Dm-755 (Yuan et al. 2003) and mgU2-28 (Huang et al., 2005b) scaRNAs, as well as of scaRNAs described in this paper. The conserved loop residues that constitute the putative CAB box are in red circles. Boxes C and D nucleotides are in black, while C′ and D′ residues are in gray circles. The reported 2′-O-methyl groups in snRNAs (Huang et al., 2005b; Myslinski et al., 1984) are marked by “m”. (B) The Drosophila C/D CAB box compared to H/ACA CAB boxes of fly and human scaRNAs. (Top panel) 32 putative CAB box sequences (positions 1–10) and their flanking nucleotides from the scaRNAs shown in (A) from D. melanogaster, D. grimshawi, D. pseudoobscura, D. virillis, and D. willistoni were aligned manually and displayed using the Pictogram algorithm (Burge et al., 1998). (Middle panel) Pictogram representation of 9 CAB tetranucleotides (positions 1–4) and their flanking sequences from the H/ACA domain of U85 scaRNA from the five Drosophila species listed above. (Bottom panel) Pictogram representation of 27 CAB tetranucleotides (positions 1–4) and their flanking sequences from human H/ACA scaRNAs, H/ACA domains of C/D-H/ACA scaRNAs, and telomerase RNA. The relative frequencies of the four nucleotides are represented by the heights of the letters.

In each of these RNAs, the sequences between boxes D′ and C′ can be folded into a stemloop structure with the apical loop harboring several highly conserved nucleotides that are also present in the two previously described RNAs (see Figure 1A). mgU4-65 RNA possesses an additional copy of this conserved sequence abutting the D′ box, which is the only copy in some Drosophila species (data not shown). Alignment of the conserved sequences from five distantly related Drosophila species, D. melanogaster, D. grimshawi, D. pseudoobscura, D. virillis, and D. willistoni, revealed a cgaGUUAnUg consensus (the residues shown by capital letters are at least 80% conserved, Figure 1B, top panel). Similarity of the first four residues to the previously described CAB box (ugAG consensus) of H/ACA scaRNAs (Richard et al., 2003) suggested functional homology. Therefore, we hypothesized that cgaGUUAnUg constitutes a CB localization signal for Drosophila box C/D scaRNAs.

To compare the putative C/D scaRNA CAB box with the H/ACA scaRNA box derived from the same organisms, we aligned the U85 scaRNA sequences from the same five Drosophila species. This analysis revealed again marked similarity at the first four positions and only very weak similarity downstream (Figure 1B, compare top and middle panels). All loop sequences carrying the CAB tetranucleotide of human H/ACA scaRNAs (bottom panel) also exhibited weak similarities downstream of the ugAG sequence. Together, these observations indicate that the putative CB localization signal for Drosophila C/D scaRNAs is related to but differs significantly from the signal found on H/ACA scaRNAs.

A 70 kD Protein UV Crosslinks to Stemloops Carrying the Putative CAB Box of Drosophila C/D scaRNAs

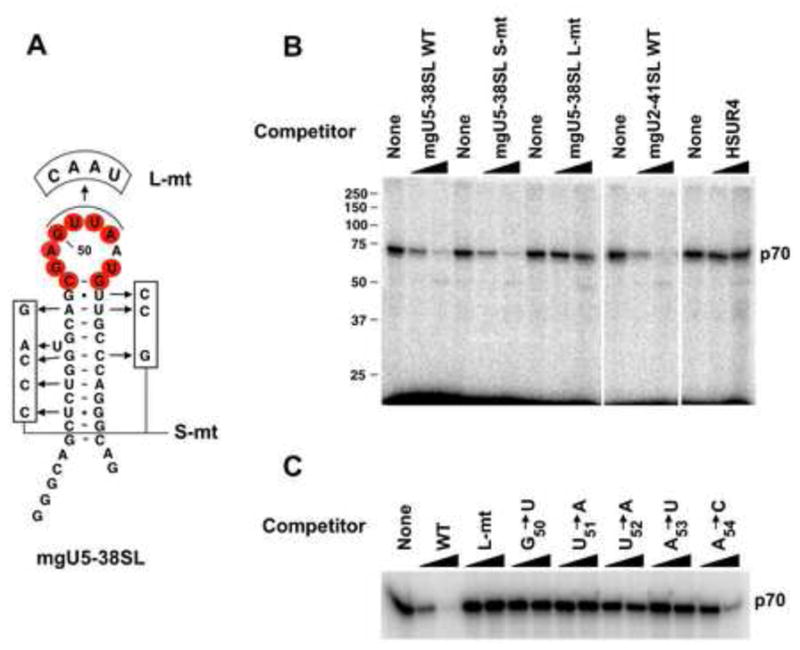

To search for factors that bind the C/D scaRNA CAB box, uniformly 32P-labeled stemloop (SL) RNAs, derived from either mgU5-38 (mgU5-38SL, Figure 2A) or mgU2-41 (mgU2-41SL, see legend to Figure 2 for description) scaRNA, were incubated in S2 nuclear extract and exposed to UV light, then treated with RNase One. A protein of apparent molecular weight 70 kD crosslinked to both mgU5-38SL and mgU2-41SL RNAs (Figure 2B, first lane and data not shown). Similar exposure of the analogous stemloops from the H/ACA domain of D. melanogaster U85 C/D-H/ACA scaRNA, which contain the canonical CAB box, did not yield any specific crosslinks (data not shown); this surprising result is explained below.

Figure 2.

CAB box-containing stemloops (SLs) of Drosophila C/D scaRNAs UV-crosslink to a 70 kD protein in S2 cell extracts. (A) Sequence and predicted secondary structure of the mgU5-38 scaRNA SL (mgU5-38SL). The residues constituting a putative CAB box are in red circles. Nucleotide substitutions in the stem and loop mutant constructs (S-mt and L-mt, respectively) are boxed. The first two G residues are not present in mgU5-38 scaRNA but were added for efficient in vitro transcription. The nucleotide numbering follows that of mgU5-38 scaRNA (see Figure 1). (B and C) UV crosslinking of 32P-labeled mgU5-38SL RNA in S2 cell nuclear extract. Incubation at 30°C was in the presence of E. coli tRNA (see Experimental Procedures for details) either with (7- or 50-fold excess) or without an additional competitor RNA, indicated at the top. Upon subsequent UV irradiation and RNase One digestion, proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. mgU2-41SL is a stemloop corresponding to nts 46–90 of mgU2-41 scaRNA (see Figure 1), while HSUR4 is a small RNA from Herpesvirus saimiri (Lee et al., 1988). In (C), the competitors indicated at the top were either wild-type (WT), L-mt, or individual point mutant mgU5-38SL RNAs.

To establish that p70 crosslinking is specific, we performed competition assays using seven- or 50-fold excess of cold competitor SL RNA along with the uniformly labeled mgU5-38SL RNA. Wild-type (WT) mgU5-38SL and mgU2-41SL RNAs competed efficiently for crosslinking to p70, as did the stem-mutated mgU5-38SL RNA, called mgU5-38SL S-mt, which contains one third of the stem residues substituted in a manner that retains the predicted secondary structure of the stem (Figure 2A and B). Conversely, the mutant mgU5-38SL, which substitutes the four most conserved residues (G50-A53) in the putative CAB box (mgU5-38SL L-mt), failed to compete, as did control HSUR4 RNA. Moreover, point mutations within the conserved 4-nt core of the CAB box also rendered an RNA unable to compete efficiently for p70 crosslinking, while substitution of the non-conserved A54 had little effect (Figure 2C). We conclude that crosslinking of Drosophila p70 to the stemloop RNA fragments of fly C/D scaRNAs is CAB box dependent.

We also attempted to use HeLa nuclear extract to identify a human p70 homolog but Drosophila mgU5-38SL and mgU2-41SL RNAs did not yield specific crosslinks (data not shown). Likewise, analogous fragments derived from the H/ACA domain of either Drosophila or human U85 scaRNA did not identify any human protein.

P70 Is a Novel WD40 Repeat Protein

To isolate Drosophila p70, we performed a three-step purification employing UV crosslinking as the assay. The protocol (Figure S2A) included fractionation on Heparin-Agarose and DEAE-Sepharose resins, followed by mgU5-38SL RNA affinity chromatography using mgU5-38SL L-mt RNA as a negative control (Figure S2B). Mass spectrometry identified the 70 kD protein selected as a conserved WD40 repeat-containing species encoded by the D. melanogaster CG9226 gene. The CG9226 protein produced in rabbit reticulocyte lysate UV crosslinked to mgU5-38SL RNA, yielding a product that co-migrated in SDS-PAGE gels with the crosslinked protein from S2 nuclear extract (Figure S3A). Moreover, the reticulocyte lysate-produced protein responded to the CAB box mutations in the UV crosslinking/competition assay in the same manner as p70 (Figure S3B). We conclude that the CG9226 protein, which has a calculated molecular mass 60.5 kD, corresponds to p70 identified by UV crosslinking. The CG9226 protein’s function is unknown.

Sequence homology searches identified p70 homologs in many vertebrate, invertebrate, protist, plant and fungal species including model organisms (Figure S4), with homology confined to the seven WD40 repeats. Human WDR79 [WD repeat domain 79 (Consortium, 2004)] is 30% identical to the Drosophila protein.

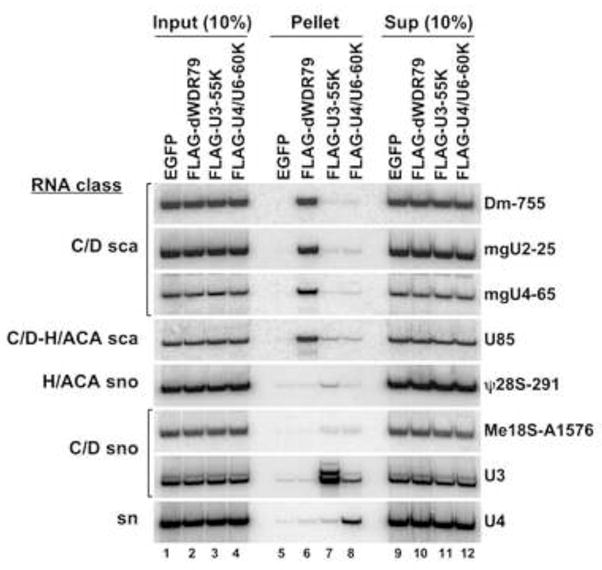

WDR79 Associates with scaRNAs in both Drosophila and Human Cells

To confirm WDR79 association with endogenous scaRNAs, we performed immunoprecipitation of the N-terminally FLAG-tagged Drosophila protein (dWDR79) transiently expressed in S2 cells. Northern blot analysis of co-precipitated RNAs revealed 7–15% recovery of all box C/D scaRNAs tested (Figure 3, lane 6, and data not shown), as well as of U85, a C/D-H/ACA scaRNA that carries two copies of the canonical CAB box. Box C/D and H/ACA snoRNAs, which carry neither the C/D nor the H/ACA CAB box, were not precipitated. As controls two FLAG-tagged fly WD40 proteins, U3-55K (lane 7) and U4/U6-60K (lane 8), which accumulated to even higher levels than dWDR79 (see Figure S5A), gave only inefficient co-selection of scaRNAs, whereas U3-55K co-selected U3 snoRNA (lane 7) and U4/U6-60K co-precipitated U4 and U6 snRNAs (lane 8 and data not shown).

Figure 3.

Drosophila WDR79 is associated with endogenous scaRNAs carrying either the C/D or H/ACA CAB box. S2 cells were transfected with FLAG-dWDR79, FLAG-U3-55K, FLAG-U4/U6-60K, or untagged EGFP construct. Whole cell extracts were precipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody and co-immunoprecipitated RNAs were fractionated by denaturing 7% PAGE alongside RNAs isolated from 10% of either input extract or IP supernatant (Sup). RNAs were analyzed by Northern blot hybridization using oligonucleotide probes (see Supplemental Data). The IP efficiency of scaRNAs ranged from 7% (mgU2-25) to 15% (mgU4-65).

Because the Drosophila C/D-H/ACA U85 scaRNA does not appear to possess the C/D CAB box, its co-precipitation suggested that dWDR79 might bind the H/ACA domain. This in turn predicted that WDR79 should also associate with H/ACA scaRNAs. Since no Drosophila H/ACA scaRNAs have yet been described, we asked whether human WDR79 (hWDR79) associates with human H/ACA scaRNAs.

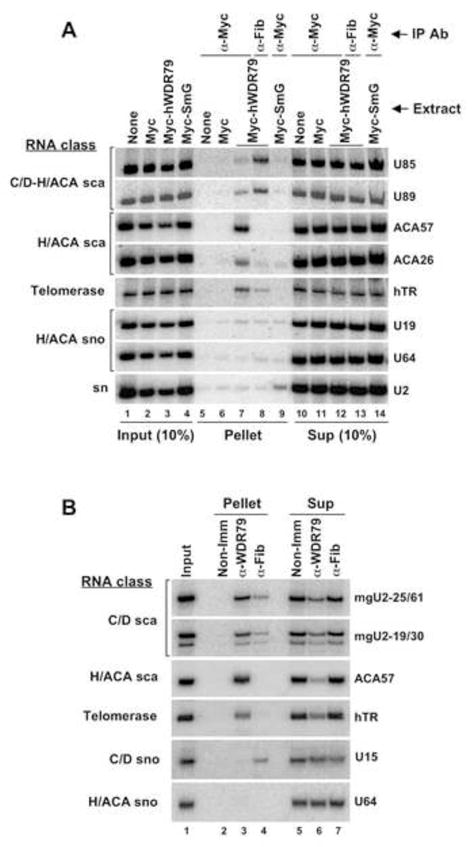

N-terminally Myc-tagged hWDR79 was transiently expressed in HEK293 cells. Northern blot analysis of RNAs precipitated with anti-Myc antibody (Figure 4A) revealed both H/ACA and C/D-H/ACA scaRNAs (lane 7), whereas only background levels were precipitated from extracts of cells expressing either the Myc peptide alone (lane 6) or the control Myc-SmG fusion (lane 9). Telomerase RNA (hTR), which possesses an H/ACA domain with a canonical CAB box, was efficiently co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-hWDR79 (lane 7), while U2 snRNA was specifically co-selected by the Myc-SmG protein (lane 9).

Figure 4.

Human WDR79 protein associates with endogenous scaRNAs and telomerase RNA. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with either Myc-hWDR79, Myc-SmG, or Myc tag construct. Whole cell extracts were exposed to either anti-Myc or anti-fibrillarin antibody as indicated at the top. The IP efficiency of scaRNAs and telomerase RNA by anti-Myc antibody ranged from 2% (U85) to 11% (ACA57). (B) HeLa nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated with either anti-WDR79 or anti-fibrillarin antibody as indicated. The IP efficiency of scaRNAs and telomerase RNA by anti-WDR79 antibody ranged from 55% (mgU2-19/30) to 81% (ACA57). Co-precipitated RNAs were fractionated by 7% denaturing PAGE alongside the RNAs isolated from either 10% (A) or 100% (B) the amount of input extract or IP supernatant (Sup). RNAs were detected by Northern blot hybridization using oligonucleotide probes (see Supplemental Data).

Unlike H/ACA and mixed domain C/D-H/ACA scaRNAs, human C/D scaRNAs were only marginally co-precipitated with the ectopically expressed Myc-hWDR79 fusion (data not shown). To check whether this was due to unstable interactions between the C/D particles and Myc-hWDR79, we crosslinked the cells with formaldehyde before lysis but saw no improvement (data not shown). Alternatively, poor co-precipitation might be due to interference of the 100 aa-long Myc-tag with binding of the ectopically expressed Myc-hWDR79 fusion to C/D particles. Therefore, we used a recently developed anti-WDR79 antibody (for Western blot, see Figure S5C) and obtained significantly improved precipitation of C/D scaRNAs from HEK293 whole cell extract, but still several-fold less efficient than that of the H/ACA species (data not shown). Efficient precipitation of C/D scaRNAs was finally achieved using HeLa cell nuclear extract prepared according to Dignam et al. (1983) (Figure 4B). Together, these data argue that in both fly and human cells, WDR79 associates with scaRNAs carrying either the C/D or H/ACA CAB box.

Two out of three known human H/ACA guide RNAs for modification of U6 snRNA (ACA12 and HBI-100) were classified as scaRNAs (Lestrade and Weber, 2006). The third known guide, ACA65, also possesses two copies of the CAB tetranucleotide. Accordingly, all three H/ACA RNAs are co-precipitated from HEK293 whole cell extracts with Myc-hWDR79, while the C/D guides for modification of U6 snRNA are not (Figure S6).

An Intact CAB Box Is Necessary for Association of an H/ACA scaRNA with WDR79

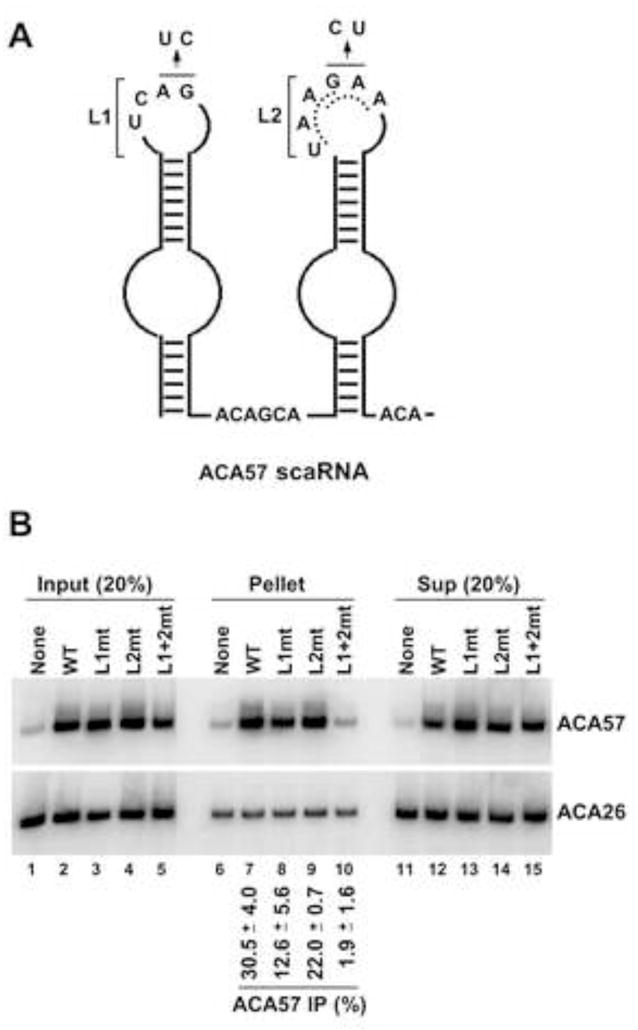

The requirements for the association of WDR79 with an H/ACA scaRNA were investigated using human ACA57 scaRNA, a typical box H/ACA species with CAB boxes in both apical loops (Figure 5A). Two-nt mutations were introduced into the CAB box either in loop 1 (L1), loop 2 (L2), or both, yielding L1mt, L2mt, or L1+2mt RNAs, respectively. In L2, which contains two overlapping CAB tetranucleotides (dotted lines), the changes were designed to mutate at least one highly conserved residue in each. L1mt, L2mt, L1+2mt, or a WT construct was co-expressed with Myc-hWDR79 in HEK293 cells and the RNAs checked for co-precipitation using anti-Myc antibody (Figure 5B). The transfected ACA57 constructs (lanes 2–5) produced 10 times more RNA than endogenous ACA57 level (lane 1).

Figure 5.

The CAB box is essential for association of an H/ACA scaRNA with WDR79 protein. (A) Secondary structure schematic of human ACA57 scaRNA. Putative CAB boxes in loop 1 (L1) and 2 (L2) as well as H (ACAGCA) and ACA box sequences are shown. Loop 2 contains two potential, overlapping CAB boxes indicated by dotted lines. The double nucleotide substitutions in L1mt and L2mt constructs are indicated. (B) Northern blot analysis of ACA57 scaRNA and its CAB mutants co-precipitating with Myc-hWDR79 fusion protein. Wild-type (WT) or mutated L1mt, L2mt, or combined (L1+2mt) RNAs were overexpressed in HEK293 cells together with Myc-tagged hWDR79. Anti-Myc precipitated RNAs were resolved by 7% denaturing PAGE and analyzed by Northern blot hybridization using oligonucleotide probes (see Supplemental Data). The endogenous ACA26 scaRNA served as an IP and gel loading control. The IP efficiency of the overexpressed wild-type or mutated ACA57 scaRNA represents an average value derived from three experiments with standard error shown (for details see Experimental Procedures).

Mutating the CAB box in loop 1 of ACA57 RNA reduced co-precipitation with hWDR79 by half compared to WT (Figure 5B, compare lane 8 with 7). Changes in loop 2 had little effect (compare lane 9 with 7). However, mutating the CAB boxes in both loops resulted in drastic reduction (15-fold) in the level of RNA precipitated (compare lane 10 with 7); the remaining trace of RNA precipitated in lane 10 most likely represents endogenous ACA57 (compare with lane 6). The levels of the control ACA26 scaRNA precipitated remained constant in each sample (lanes 6–10). These data demonstrate a requirement for the CAB box in human H/ACA scaRNAs to associate with the hWDR79 protein.

An Intact ACA Box Is also Necessary for the Association of a C/D-H/ACA scaRNA with WDR79

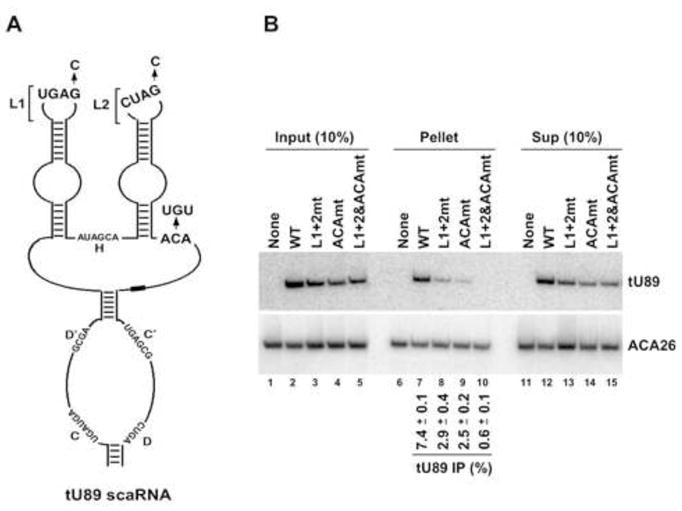

Although required, the CAB box alone appears insufficient for stable association of an H/ACA scaRNA with WDR79. This is evident from the lack of competition for dWDR79 by short stemloop RNA fragments carrying the H/ACA CAB box in UV-crosslinking assay in Drosophila extract (data not shown). Since Richard et al. (2003) demonstrated that the ACA triplet, in addition to CAB box, is essential for the CB localization of human C/D-H/ACA U85 scaRNA, we tested whether box ACA is also required for the association of a scaRNA with the hWDR79 protein. Since U85 is poorly co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged hWDR79, nor could ACA57 RNA be used since mutating box ACA in a single domain H/ACA scaRNA leads to destabilization (Ganot et al., 1997), we chose yet another C/D-H/ACA scaRNA, U89. We tagged U89 by substituting 6 nts in the spacer between the C/D and H/ACA domains (to make tU89, Figure 6A) and used a probe that specifically detects U89 expressed from transfected constructs.

Figure 6.

Both CAB and ACA boxes are required for the association of human U89 C/D-H/ACA scaRNA with WDR79 protein. (A) Secondary structure schematic of tagged human U89 (tU89) scaRNA. Putative CAB boxes in loops 1 (L1) and 2 (L2) as well as H, ACA, C, C′, D and D′ motifs, are indicated. Loop and box ACA substitutions in the mutant tU89 constructs are shown. A 6 nt-long tag generated by changing nucleotides 237–242 into complementary residues is represented by a bar. (B) Northern blot analysis of tU89 scaRNA and its mutants co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-hWDR79 protein. Either wild-type (WT), CAB-mutated (L1+2mt), box ACA-mutated (ACAmt), or combined CAB- and ACA-mutated (L1+2&ACAmt) tU89 scaRNA was co-expressed with Myc-hWDR79 in HEK293 cells. Anti-Myc precipitated RNAs were resolved by 7% denaturing PAGE and analyzed by Northern blot hybridization using oligonucleotide probes (see Supplemental Data). The IP efficiency of either wild-type or mutated tU89 scaRNA represents an average of two experiments with standard error shown (for details see Experimental Procedures).

Changing the highly conserved G residue to C in both copies of the CAB box in tU89 (see Figure 6A) resulted in a 2.5-fold reduction in its co-precipitation with hWDR79 (Figure 6B, compare lane 8 to 7). Similarly, substituting the ACA box yielded 3-fold lower precipitation (compare lane 9 to 7). Combining the CAB and ACA box mutations resulted in a 12-fold decrease in precipitation efficiency (compare lane 10 with 7). We conclude that both CAB and ACA boxes are necessary for stable association of U89 with hWDR79.

WDR79 Localizes to CBs in Human Cells

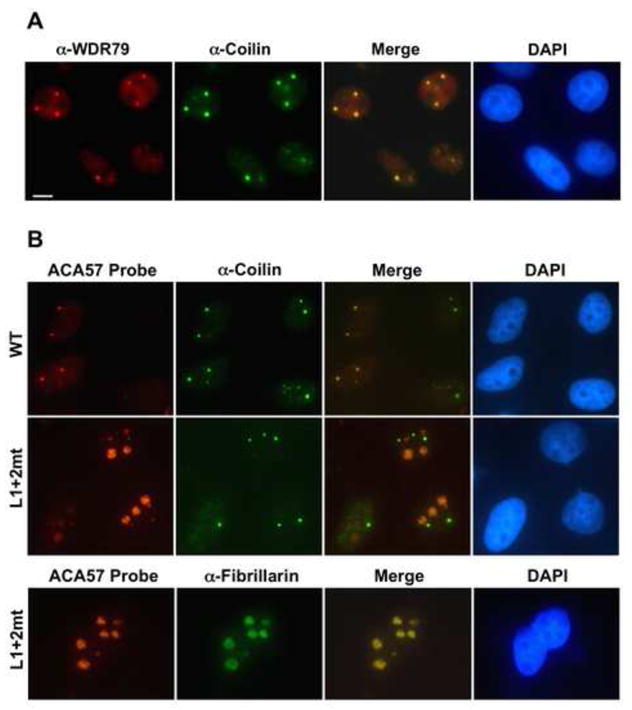

Since we found that the requirements for scaRNA association with WDR79 mimic those deduced for the CB localization (Richard et al., 2003), we asked whether endogenous human WDR79 and transiently expressed Myc-hWDR79 fusion proteins localize to CBs in HeLa cells. In immunofluorescence experiments, anti-WDR79 weakly stains the entire nucleoplasm with clear nucleolar exclusion (Figure 7A). A few bright round bodies that co-stain with anti-coilin, identifying CBs, appear in nearly all cells. In cells expressing the fusion protein, anti-Myc stains the entire nucleus diffusely with some nucleolar exclusion (Figure S7), and a few CBs in most cells. The intensity of the diffuse nuclear staining varies even between cells showing similar CB staining, most likely reflecting differential expression of the fusion protein, which accumulates at 5–10-fold the level of endogenous hWDR79 (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Association with hWDR79 is required for CB localization of a human scaRNA. (A) Subcellular localization of hWDR79 in HeLa cells using rabbit polyclonal antibody. (B) Mislocalization of a CAB box mutant ACA scaRNA. Either WT or L1+2mt ACA57 (see Figure 5A) was transiently overexpressed in HeLa cells and detected by FISH. CBs, nuclei, and nucleoli were visualized with anti-coilin, DAPI, and anti-fibrillarin staining, respectively. Scale bar; 10μm.

Association with WDR79 Is Required for the Localization of a scaRNA to CBs

To check whether binding to WDR79 is necessary for a scaRNA to accumulate in CBs, we localized transiently expressed WT and L1+2mt CAB-box mutant ACA57 RNA, which does not bind WDR79 (see Figure 5), by in situ hybridization (Figure 7B). While the WT scaRNA localizes predominantly to CBs with weaker signal in the nucleoplasm (top row and data not shown), the L1+2mt RNA accumulates mostly in nucleoli with only residual amounts in CBs (middle and bottom rows). Thus, the CB localization of ACA57 scaRNA depends on its association with WDR79.

DISCUSSION

Despite identification of the CAB box in H/ACA scaRNAs and telomerase RNA years ago (Jady et al., 2004; Richard et al., 2003), the trans-acting factor(s) responsible for localizing these RNAs to CBs remained elusive. The mechanism for localizing the other class of scaRNAs, C/D scaRNAs, to CBs was even less understood. Here, we have identified in Drosophila C/D scaRNAs a sequence element related to the CAB box, referred to as the C/D CAB box (Figure 1B, top panel). We isolated a fly WD40 repeat protein whose UV-crosslinking is dependent on this C/D CAB box (Figure 2) and is associated with cellular box C/D and mixed domain C/D-H/ACA scaRNAs from Drosophila (Figure 3). Its human homolog, WDR79, associates with C/D, H/ACA, or mixed domain scaRNAs from human, as well as with telomerase RNA (Figure 4). We show that hWDR79 binds to human H/ACA and mixed domain scaRNAs in a CAB box-dependent manner and that its binding to mixed domain species also requires the ACA motif (Figures 5 and 6). Most importantly, we observe that a human H/ACA scaRNA mutated in its CAB box and thus unable to bind WDR79 mislocalizes to nucleoli in HeLa cells (Figure 7). Human WDR79 was recently independently identified as a component of the telomerase holoenzyme (Venteicher et al., 2009).

A CAB-like Box in Drosophila C/D scaRNAs

To begin our search for signal(s) that facilitate the localization of C/D scaRNAs to CBs, we identified four novel Drosophila box C/D scaRNA species (Figures 1 and S1). These four plus the two previously known Drosophila C/D scaRNAs (Huang et al., 2005b; Yuan et al., 2003) all possess a 10 nt-long conserved sequence that we hypothesized to be a novel CB localization signal because of its presence in scaRNAs but not snoRNAs and its similarity to the previously characterized CAB box localization signal of H/ACA scaRNAs and telomerase RNA [ugAG; (Jady et al., 2004; Richard et al., 2003)]. Similarity is most evident at positions 3 and 4, where an AG dinucleotide is highly conserved in both the C/D and H/ACA CAB boxes (Figure 1B). Accordingly, only these two residues in the H/ACA CAB box were previously found to be essential for the CB localization of human U85 C/D-H/ACA scaRNA (Richard et al., 2003). The UUA triplet, which is invariant in the C/D CAB box, is less well conserved in extended H/ACA CAB consensus sequences from both Drosophila and human (see Figure 1B, middle and bottom panels). The apparent lack of similarity between Drosophila C/D and H/ACA CAB boxes at these positions may be artifactual since the H/ACA consensus is derived from only a single scaRNA, U85 (see Figure 1B, middle panel).

Except for mgU4-65, all Drosophila C/D scaRNAs possess a single copy of the CAB box invariably located in the apical loop of a stemloop structure (Figure 1 and data not shown). mgU4-65 RNA in the one third of Drosophila species whose genomes have been sequenced possesses only a single CAB box copy. Interestingly, in those species this copy abuts box D′ (data not shown), suggesting that the position of the CAB box in C/D scaRNAs is not restricted to apical loops. In contrast, in H/ACA scaRNAs, the CAB box always appears in apical loops (Lestrade and Weber, 2006; Richard et al., 2003), another difference between C/D and H/ACA CAB boxes.

The identification of a novel CAB box sequence provided a tool to search for factors mediating the localization of scaRNAs to CBs. Indeed, a 70 kD Drosophila protein specifically UV crosslinked to short RNAs carrying this sequence (Figure 2) and was identified as a WD40 repeat-containing protein whose human homolog is termed WDR79 (Consortium, 2004).

In vitro binding of p70 (dWDR79) to stemloop RNAs requires the most conserved residues of the CAB box, i.e. G4, the invariant UUA triplet at position 5–7 and U9 (see Figures 1B, top panel and 2). The identities of the stem nucleotides do not seem important, and whether a stem is required at all remains to be established.

The gene encoding hWDR79 has been implicated in human disease. Its single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been linked to estrogen receptor negative breast cancer (Garcia-Closas et al., 2007) and benzene-induced hematotoxicity (Lan et al., 2008). It is not known whether the SNP changes influence the levels and/or function of hWDR79, or whether they affect regulatory elements important for the expression of the closely positioned TP53 gene, encoding the tumor suppressor protein p53. Since the WDR79 and TP53 genes are separated by only 1 kb and are oriented head-to-head, their expression may be co-regulated.

Association of WDR79 with Box C/D scaRNPs

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments on both Drosophila and human cell extracts (Figures 3 and 4) demonstrated that WDR79 associates with endogenous box C/D scaRNAs. Since the protein can be crosslinked in vitro to short stemloops, at least in Drosophila its association with scaRNPs depends solely or predominantly on the CAB box. This notion is consistent with significant variability in the location of the CAB box relative to the main body in different scaRNAs. The stemloops carrying the CAB box vary greatly in length and the CAB sequence can even directly abut box D (see Figure 1 and data not shown). UV crosslinking establishes that the Drosophila WDR79 protein interacts directly with RNA.

In contrast to fly, the CAB box in human C/D scaRNAs is not readily apparent. Although human C/D scaRNAs are associated with WDR79 as judged by their efficient and specific immunoprecipitation from HeLa cell nuclear extract (Figure 4B), most do not possess sequences that conform to the Drosophila C/D CAB box consensus. Divergence of the C/D CAB boxes in these two organisms is supported by the failure of in vitro translated human WDR79 to crosslink to Drosophila C/D CAB box-containing stemloops (data not shown). Since human C/D scaRNAs are on average 3 times longer with poorly defined secondary structures, assessing the significance of sequences that are C/D CAB box related will require further experiments.

Association of WDR79 with Box H/ACA scaRNPs and Telomerase RNP

Although we detected and purified dWDR79 using RNA fragments from Drosophila box C/D scaRNAs, the protein also associates with box H/ACA scaRNAs and H/ACA domains of C/D-H/ACA scaRNAs (Figures 3–6 and Venteicher et al., 2009). This association appears to be conserved throughout the entire animal and plant kingdoms, since both the WDR79 protein (Figure S4 and data not shown) and the H/ACA CAB box (Richard et al., 2003; our observation) are retained. Accordingly, we demonstrated the association of WDR79 with scaRNAs carrying the H/ACA CAB box in both human and Drosophila (Figures 3 and 4).

The association of hWDR79 with human U89 C/D-H/ACA scaRNA requires at least two RNA elements, the CAB and ACA boxes (Figure 6), which we predict is true of all C/D-H/ACA and H/ACA scaRNAs, as well as of telomerase RNA. While either WDR79 alone or a WDR79-containing complex most likely binds the CAB box directly, interaction with the ACA triplet is probably indirect. In the crystal structure of an archeal H/ACA RNP (Li and Ye, 2006), the ACA motif lies on the opposite side from the apical loop, whose scaRNA counterpart harbors the CAB box. Moreover, the ACA triplet is bound by the PUA domain of the pseudouridine synthase and is essential for the binding of other core proteins (Baker et al., 2005; Richard et al., 2003). This suggests that WDR79 interacts with one or more polypeptides of the H/ACA core complex, in addition to the CAB box. Indeed, an RNA-independent interaction between WDR79 and the pseudouridine synthase has been detected (Venteicher et al., 2009). Accordingly, the H/ACA CAB box sequence may be shorter than its C/D counterpart, but its location relative to the main body of scaRNAs may be more rigidly defined. Dependence on the core complex would provide a rationale for the failure of short stemloops carrying the H/ACA CAB box to compete for WDR79 in the in vitro crosslinking assay (data not shown).

Fu and Collins (2006) proposed that two Sm proteins, SmB and SmD3, associate with a fraction of H/ACA scaRNAs and telomerase RNA and that this association is CAB box dependent, at least for telomerase. It will be interesting to learn whether the Sm proteins cooperate or compete with WDR79 for CAB box binding.

Unexpectedly, in addition to canonical H/ACA scaRNA family members that modify polII-transcribed snRNAs, the H/ACA guides for modification of U6 snRNA also associate with WDR79 (Figure S6). A CAB box sequence is present in all known H/ACA guides for U6 snRNA modification (Lestrade and Weber, 2006; our observations), predicting their CB localization, even though it was earlier concluded that pseudouridylation of U6 snRNA takes place in nucleoli (Ganot et al., 1999). Additional studies are necessary to resolve this apparent discrepancy.

Multiple Roles for WDR79 in Nuclear RNP Localization and Processing

The required binding of hWDR79 to achieve CB localization of human ACA57 H/ACA scaRNA (Figure 7B) strongly suggests that this protein is involved in the sub-nuclear localization of all scaRNPs. Moreover, the requirements we observe for the association of human U89 C/D-H/ACA scaRNA with hWDR79 mirror those deduced by Richard et al. (2003) for the localization of an analogous C/D-H/ACA scaRNA, U85, to CBs. The CAB mutation in U89 (see Figure 6A) is analogous to one that in human telomerase RNA leads to its mislocalization (Jady et al., 2004; Theimer et al., 2007) and, consequently, to the inhibition of telomere elongation (Cristofari et al., 2007). Indeed, a role for WDR79 in the CB localization of human telomerase and in telomere synthesis has been recently demonstrated (Venteicher et al., 2009).

A WD40 repeat protein, MTAP, has been recently described to associate with SLA1 RNP, an H/ACA particle involved in pseudouridylation of splice leader RNA, in Trypanosoma brucei (Zamudio et al., 2009). Although suggested to be unique to kinetoplastids, MTAP exhibits sequence homology with WDR79 from both human and Drosophila (Figure S4) arguing that MTAP is a T. brucei homolog of WDR79. The WD40 domains of MTAP and human WDR79 are 27% identical, compared to only 19% identity between MTAP’s and the next most similar WD40 domains in the human database. MTAP tethers the cap 2′-O-methyltranferase 1 to the SLA1 RNP. MTAP-null trypanosome lines not only exhibit cap undermethylation but also defects in the splice leader RNA 3′ end formation, suggesting additional roles for the MTAP protein. Since splice leader RNP is an Sm class snRNP, WDR79 may function similarly in snRNA biogenesis in higher eukaryotes. Thus, WDR79 emerges as a major player in the localization and processing of small nuclear RNP complexes, exploiting the potential of the WD40 motif to serve as an adaptor for integrating multiple processes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Nucleotide Database Searches and Sequence Alignments

The query sequences to identify novel box C/D guide RNAs for 2′-O-methylation of Drosophila spliceosomal snRNAs were as follows: TGATGA(N)3-5(antisense element)CTGA(N)10TTANT(N)10TGATGA(N)12-14CTGA or TGATGA(N)12-14CTGA(N)10TTANT(N)10TGATGA(N)3-5(antisense element)CTGA. The antisense elements were 11 nt-long. The public Drosophila databases were queried on the NCBI server using the BLAST algorithm. Sequence alignments were performed using the T-coffee program with the default parameters (Notredame et al., 2000).

Plasmids and Mutagenesis

Plasmids containing full-length cDNAs encoding D. melanogaster WDR79 [clone (cl) AT03686], U3-55K (cl LD17611), and U4/U6-60K (cl SD09427) were obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (Bloomington, IN), while that encoding human WDR79 (cl 2924101) was purchased from Open Biosystems.

D. melanogaster FLAG-WDR79, FLAG-U3-55K, and FLAG-U4/U6-60K expression plasmids were constructed by excising the EGFP ORF (BamHI/NotI sites) from the pActin5C-EGFP-N1 plasmid (gift from H. Agaisse, Yale University) and replacing it with an N-terminally FLAG-tagged ORF. To PCR-amplify the WDR79, U3-55K and U4/U6-60K cDNAs, KT377/KT378, KT394/KT395, and KT396/KT397 pairs of primers were used, respectively.

The human Myc-WDR79 expression plasmid was constructed by inserting a PCR-amplified WDR79 cDNA, using KT343 and KT344 primers, into the EcoRI-XhoI site of the CS3+MT vector.

The pcDNA3-ACA57 plasmid was obtained by inserting into the BamHI/EcoRI site of the pcDNA3 vector a PCR-amplified fragment of the human CHD4 gene (host gene for ACA57 scaRNA) using KT367 and KT368 primers.

The pcDNA3-U89 plasmid was constructed as above except that the insert was generated by amplifying a portion of the human PHB2 gene (host gene for U89 scaRNA) using KT375 and KT376 primers.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell Lines and Transfections

Drosophila S2, human HEK293, and HeLa cells were transfected using the Effectene (Qiagen), the TransIT-293 (Mirus Bio) reagents, and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively, according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Whole Cell Lysate Preparation and Immunoprecipitation

Forty-eight hours after transfection, HEK293 cells, grown in 10 cm dishes, were washed with 10 ml and scraped in 1.5 ml of PBS. After pelleting, the cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 0.05% NP-40), incubated on ice for 10 min, and lysed by passing 5–10 times through a 25G1½ needle. After addition NaCl to 150 mM, cell debris was pelleted for 10 min at 15,000g at 4°C and the supernatant was used for immunoprecipitation.

The S2 cell lysates were prepared as described above for HEK293 cells except that cells were passed through the needle 20 times, and after addition of NaCl, they were sonicated 3 times for 10 sec with 15 sec intervals on ice.

For immunoprecipitation of Myc- and FLAG-tagged proteins or of human WDR79, monoclonal 9E10 and M2 antibodies (Sigma) or rabbit polyclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals) were used, respectively. Immunoprecipitations were performed according to a standard protocol (Steitz, 1989). The immunoprecipitation efficiency represents the amount of RNA recovered in the pellet divided by the amount recovered from both the pellet and the supernatant. The immunoprecipitation efficiency of ectopically expressed scaRNAs was normalized to that of endogenous scaRNA.

Nuclear Extract Preparation and UV Crosslinking

Nuclear extracts were prepared by either salt extraction or sonication of nuclei isolated as described (Dignam et al., 1983). For salt extraction, the Dignam protocol was followed (Dignam et al., 1983). For sonication, the nuclei were suspended in buffer D (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT and 0.5 mM PMSF) and sonicated 4 times for 30 sec (with 30 sec intervals) on ice with the Branson sonicator, followed by spinning out the debris at 16,000g.

For UV crosslinking, 50,000 cpm (spec. activity 5×105 cpm/pmole) of RNA, uniformly labeled with [α-32P]UTP, were incubated for 30 min at 30°C with 5μl of nuclear extract (or 1 μl of a TNT reaction programmed with CG9226 cDNA) in a 10 μl mixture containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM ATP, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 0.25 mM DTT, and 10μg E. coli tRNA. The reaction mixture was irradiated twice on ice with 860 mJ/cm2 and then treated with 5 units of RNase One (Promega) for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE.

Immunofluorescence and In Situ Hybridization

IF and FISH were performed according to standard protocols (Pawlicki and Steitz, 2008). To detect ACA57 scaRNA, a cocktail of KT428 and KT429 oligonucleotides (see Supplemental Data) was used. The probes were labeled with DIG-dUTP using the 3′ DIG Tailing kit (Roche) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To visualize hWDR79 or coilin, 500x diluted rabbit polyclonal (Novus Biologicals) or mouse monoclonal C4 antibody (gift from Greg Matera, Chapel Hill, NC), respectively, was used. Fluorescent images were captured with an Axioplan-II microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a digital CCD camera (Hamamatsu).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Matera, Sumit Borah, Nikolay Kolev, and Dennis Mishler for sharing antibodies, cell extracts, plasmids, and protocols. We also thank Andrei Alexandrov, Nikolay Kolev, Jan Pawlicki, and Shobha Vasudevan for critical reading the manuscript, Angie Miccinello for editorial help, and the rest of the Steitz lab for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by grant R01GM026154 from the NIGMS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or the NIH. J.A.S is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Accession Numbers

Nucleotide sequences of D. melanogaster mgU2-25, mgU2-41, mgU4-65, and mgU5-38 scaRNAs are available in the Third Party Annotation Section of the GenBank database under the accession numbers 1186753, 1186817, 1186819, and 1186821.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baker DL, Youssef OA, Chastkofsky MI, Dy DA, Terns RM, Terns MP. RNA-guided RNA modification: functional organization of the archaeal H/ACA RNP. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1238–1248. doi: 10.1101/gad.1309605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge CB, Padgett RA, Sharp PA. Evolutionary fates and origins of U12-type introns. Mol Cell. 1998;2:773–785. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo-Fonseca M. New clues to the function of the Cajal body. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:726–727. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioce M, Lamond AI. Cajal bodies: a long history of discovery. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:105–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.103738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium IHGS. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari G, Adolf E, Reichenbach P, Sikora K, Terns RM, Terns MP, Lingner J. Human telomerase RNA accumulation in Cajal bodies facilitates telomerase recruitment to telomeres and telomere elongation. Mol Cell. 2007;27:882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzacq X, Jady BE, Verheggen C, Kiss AM, Bertrand E, Kiss T. Cajal body-specific small nuclear RNAs: a novel class of 2′-O-methylation and pseudouridylation guide RNAs. EMBO J. 2002;21:2746–2756. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominski Z, Marzluff WF. Formation of the 3′ end of histone mRNA: getting closer to the end. Gene. 2007;396:373–390. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Collins K. Human telomerase and Cajal body ribonucleoproteins share a unique specificity of Sm protein association. Genes Dev. 2006;20:531–536. doi: 10.1101/gad.1390306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganot P, Caizergues-Ferrar M, Kiss T. The family of box ACA small nucleolar RNAs is defined by an evolutionarily conserved secondary structure and ubiquitous sequence elements essential for RNA accumulation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:941–956. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganot P, Jady BE, Bortolin ML, Darzacq X, Kiss T. Nucleolar factors direct the 2′-O-ribose methylation and pseudouridylation of U6 spliceosomal RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6906–6917. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Closas M, Kristensen V, Langerod A, Qi Y, Yeager M, Burdett L, Welch R, Lissowska J, Peplonska B, Brinton L, et al. Common genetic variation in TP53 and its flanking genes, WDR79 and ATP1B2, and susceptibility to breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2532–2538. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZP, Chen CJ, Zhou H, Li BB, Qu LH. A combined computational and experimental analysis of two families of snoRNA genes from Caenorhabditis elegans, revealing the expression and evolution pattern of snoRNAs in nematodes. Genomics. 2007;89:490–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZP, Zhou H, He HL, Chen CL, Liang D, Qu LH. Genome-wide analyses of two families of snoRNA genes from Drosophila melanogaster, demonstrating the extensive utilization of introns for coding of snoRNAs. RNA. 2005a;11:1303–1316. doi: 10.1261/rna.2380905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZP, Zhou H, Qu LH. Maintaining a conserved methylation in plant and insect U2 snRNA through compensatory mutation by nucleotide insertion. IUBMB Life. 2005b;57:693–699. doi: 10.1080/15216540500306983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jady BE, Bertrand E, Kiss T. Human telomerase RNA and box H/ACA scaRNAs share a common Cajal body-specific localization signal. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:647–652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jady BE, Darzacq X, Tucker KE, Matera AG, Bertrand E, Kiss T. Modification of Sm small nuclear RNAs occurs in the nucleoplasmic Cajal body following import from the cytoplasm. EMBO J. 2003;22:1878–1888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jady BE, Kiss T. A small nucleolar guide RNA functions both in 2′-O-ribose methylation and pseudouridylation of the U5 spliceosomal RNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:541–551. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss AM, Jady BE, Bertrand E, Kiss T. Human box H/ACA pseudouridylation guide RNA machinery. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5797–5807. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5797-5807.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss AM, Jady BE, Darzacq X, Verheggen C, Bertrand E, Kiss T. A Cajal body-specific pseudouridylation guide RNA is composed of two box H/ACA snoRNA-like domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4643–4649. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss T, Fayet E, Jady BE, Richard P, Weber M. Biogenesis and intranuclear trafficking of human box C/D and H/ACA RNPs. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:407–417. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, Zhang L, Shen M, Jo WJ, Vermeulen R, Li G, Vulpe C, Lim S, Ren X, Rappaport SM, et al. Large-scale evaluation of candidate genes identifies associations between DNA repair and genomic maintenance and development of benzene hematotoxicity. Carcinogenesis. 2008 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SI, Murthy SC, Trimble JJ, Desrosiers RC, Steitz JA. Four novel U RNAs are encoded by a herpesvirus. Cell. 1988;54:599–607. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lestrade L, Weber MJ. snoRNA-LBME-db, a comprehensive database of human H/ACA and C/D box snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D158–162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Ye K. Crystal structure of an H/ACA box ribonucleoprotein particle. Nature. 2006;443:302–307. doi: 10.1038/nature05151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JL, Murphy C, Buszczak M, Clatterbuck S, Goodman R, Gall JG. The Drosophila melanogaster Cajal body. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:875–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maden BEH. The numerous modified nucleotides in eukaryotic ribosomal RNA. Progr Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1990;39:241–303. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massenet S, Mougin A, Branlant C. Posttranscriptional modifications in the U small nuclear RNAs. In: Grosjean H, Benne R, editors. Modification and Editing of RNA. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1998. pp. 201–227. [Google Scholar]

- Matera AG, Shpargel KB. Pumping RNA: nuclear bodybuilding along the RNP pipeline. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier UT. How a single protein complex accommodates many different H/ACA RNAs. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myslinski E, Branlant C, Wieben ED, Pederson T. The small nuclear RNAs of Drosophila. J Mol Biol. 1984;180:927–945. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic D, Tanackovic G, Kramer A. A role for Cajal bodies in the final steps of U2 snRNP biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4423–4433. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SB, Bellini M. The assembly of a spliceosomal small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6482–6493. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlicki JM, Steitz JA. Primary microRNA transcript retention at sites of transcription leads to enhanced microRNA production. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:61–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes O, Pikaard CS. siRNA and miRNA processing: new functions for Cajal bodies. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichow SL, Hamma T, Ferre-D’Amare AR, Varani G. The structure and function of small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1452–1464. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard P, Darzacq X, Bertrand E, Jady BE, Verheggen C, Kiss T. A common sequence motif determines the Cajal body-specific localization of box H/ACA scaRNAs. EMBO J. 2003;22:1–11. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek D, Neugebauer KM. The Cajal body: a meeting place for spliceosomal snRNPs in the nuclear maze. Chromosoma. 2006;115:343–354. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz JA. Immunoprecipitation of ribonucleoproteins using autoantibodies. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:468–481. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terns M, Terns R. Noncoding RNAs of the H/ACA family. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:395–405. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terns MP, Terns RM. Small nucleolar RNAs: versatile trans-acting molecules of ancient evolutionary origin. Gene Expr. 2002;10:17–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theimer CA, Jady BE, Chim N, Richard P, Breece KE, Kiss T, Feigon J. Structural and functional characterization of human telomerase RNA processing and Cajal body localization signals. Mol Cell. 2007;27:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tycowski KT, Aab A, Steitz JA. Guide RNAs with 5′ caps and novel box C/D snoRNA-like domains for modification of snRNAs in metazoa. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1985–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venteicher AS, Abreu EB, Meng Z, McCann KE, Terns RM, Veenstra TD, Terns MP, Artandi SE. A human telomerase holoenzyme protein required for Cajal body localization and telomere synthesis. Science. 2009;323:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1165357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YT, Shu MD, Steitz JA. Modifications of U2 snRNA are required for snRNP assembly and pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1998;17:5783–5795. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Klambt C, Bachellerie JP, Brosius J, Huttenhofer A. RNomics in Drosophila melanogaster: identification of 66 candidates for novel non-messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2495–2507. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio JR, Mittra B, Chattopadhyay A, Wohlschlegel JA, Sturm NR, Campbell DA. Trypanosoma brucei spliced leader RNA maturation by the cap 1 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase and SLA1 H/ACA snoRNA pseudouridine synthase complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1202–1211. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01496-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.