Abstract

Higher plants share with animals a responsiveness to the Ca2+ mobilizing agents inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) and cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR). In this study, by using a vesicular 45Ca2+ flux assay, we demonstrate that microsomal vesicles from red beet and cauliflower also respond to nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), a Ca2+-releasing molecule recently described in marine invertebrates. NAADP potently mobilizes Ca2+ with a K1/2 = 96 nM from microsomes of nonvacuolar origin in red beet. Analysis of sucrose gradient-separated cauliflower microsomes revealed that the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ pool was derived from the endoplasmic reticulum. This exclusively nonvacuolar location of the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ pathway distinguishes it from the InsP3- and cADPR-gated pathways. Desensitization experiments revealed that homogenates derived from cauliflower tissue contained low levels of NAADP (125 pmol/mg) and were competent in NAADP synthesis when provided with the substrates NADP and nicotinic acid. NAADP-induced Ca2+ release is insensitive to heparin and 8-NH2-cADPR, specific inhibitors of the InsP3- and cADPR-controlled mechanisms, respectively. However, NAADP-induced Ca2+ release could be blocked by pretreatment with a subthreshold dose of NAADP, as previously observed in sea urchin eggs. Furthermore, the NAADP-gated Ca2+ release pathway is independent of cytosolic free Ca2+ and therefore incapable of operating Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. In contrast to the sea urchin system, the NAADP-gated Ca2+ release pathway in plants is not blocked by L-type channel antagonists. The existence of multiple Ca2+ mobilization pathways and Ca2+ release sites might contribute to the generation of stimulus-specific Ca2+ signals in plant cells.

A wide variety of environmental stimuli is transduced via Ca2+-based signaling pathways in plants (1). Low resting levels of cytosolic free calcium ([Ca2+]c) are sustained by Ca2+-ATPases and additionally, at the vacuolar membrane, by a Ca2+/H+ antiporter, which removes Ca2+ from the cytosol. Elevation of [Ca2+]c during signaling occurs through the opening of one or more classes of Ca2+-permeable ion channel that are variously located at the plasma membrane, vacuolar membrane, or endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Targets for Ca2+ signals include Ca2+/calmodulin-domain protein kinases, a calcineurin B-subunit homolog, or Ca2+-dependent ion channels.

Cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) act as signaling molecules for the mobilization of Ca2+ stores in both plant (2–6) and animal cells (7, 8). More recently, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), a metabolite of NADP, also has been identified as a potent mobilizer of Ca2+ in sea urchin eggs, pancreatic acinar cells, and brain (9–11). Pharmacological and fractionation studies (9, 11, 12) demonstrate that both the release mechanism and the Ca2+ stores sensitive to NAADP are distinct from those that are sensitive to InsP3 and cADPR. NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release also displays biochemical features not found in the other two ligand-gated systems. NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release is not [Ca2+]c-dependent (13, 14) and therefore, unlike InsP3- and cADPR-dependent release, cannot contribute to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. Inhibitors of L-type channels (dihydropyridines, verapamil, and diltiazem) block NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release, indicating that the release pathway might share structural similarities to L-type Ca2+ channels (15, 16). In addition, NAADP exhibits a unique self-desensitization mechanism: Pretreatment with a low (<3 nM), subthreshold dose of NAADP inhibits Ca2+ release by a subsequent saturating dose of NAADP (16, 17). This self-inactivation phenomenon of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release after Ca2+ signaling during fertilization suggests that NAADP plays a physiological role in the fertilization process (18). Inhibition of fertilization-associated membrane expansion in ascidian oocytes by NAADP led to a similar conclusion (19). Mammalian systems contain the enzymatic machinery to synthesize and degrade NAADP (11, 20), and the presence of endogenous NAADP has been inferred in Arabidopsis thaliana with desensitization experiments (2). However, NAADP is far from being described as a ubiquitously important [Ca2+]c modulator because NAADP-dependent Ca2+-mobilization has yet to be elucidated in systems other than marine invertebrates, pancreatic acinar cells, and brain (9–11).

In this study, we use vesicles derived from Beta vulgaris L. tap roots and Brassica oleracea L. inflorescences to investigate the potential of NAADP to mobilize Ca2+ in plants. The presence of highly active Ca2+ sequestration mechanisms (21–24) and Ca2+ channels, including ligand-gated channels (3, 4, 25, 26), underlines the importance of Ca2+ metabolism in these experimental systems.

Materials and Methods

Red Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) Membrane Production.

Microsomes were isolated from the storage root of greenhouse-grown red beet as described previously (27). Vacuole-enriched vesicles were produced by using sucrose density gradient centrifugation of a microsomal preparation as reported (27), but with the following modifications: 1 μg/ml soybean trypsin-inhibitor, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 5 mM benzamidine⋅HCl were added to the homogenization medium, replacing nupercaine. Soybean trypsin inhibitor (1 μg/ml) and leupeptin (1 μg/ml) also were included in the suspension medium. After separation of membranes on a sucrose step-gradient (27), the pink protein band at the 10–23% (wt/wt) sucrose interphase was removed and diluted 10-fold into calcium transport buffer (see Ca2+ Transport Assay), which included 1 mM DTT. A further centrifugation step followed at 80,000 × g for 30 min. The final vacuolar membrane pellet was resuspended in the same buffer, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use.

Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L.) Membrane Production.

Microsomes were isolated from the outermost 5 mm of cauliflower inflorescences as described (23). The yield was typically 0.5–0.8 mg of protein per g of fresh weight starting material. Microsomes were further separated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation as previously reported (26). Briefly, 2 ml of microsomal vesicles (10–15 mg/ml) were loaded onto a 30-ml, 10–45% (wt/wt) linear sucrose gradient, centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 6 h at 4°C, and fractionated from the top into 2-ml fractions. Sucrose concentration was measured by refractometry. Plasma membrane preparations were obtained by aqueous two-phase partitioning of the microsomal fraction as previously described (28).

NAADP Production by Cauliflower Homogenates.

Approximately 15 g of cauliflower inflorescence (top 2 mm) was homogenized in 30 ml of assay medium comprised of 340 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Hepes (pH 5.0) with 1.7% (vol/vol) plant cell protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). The homogenate was filtered through two layers of muslin, and Ca2+ was removed with Chelex resin (Sigma). Aliquots (5 μl) were tested for the presence of NAADP, and for its production from 0.25 mM β-NADP and 7 mM nicotinic acid, by using the NAADP densitization method (29) with a sea urchin microsome Ca2+-release bioassay. NAADP was quantified as described (29). Values reported are the means from two independent determinations.

Protein Determination.

Protein concentration was determined with a Bio-Rad assay kit as described (30). BSA was used as a standard.

Marker Enzyme Assays.

Marker enzyme assays were used to determine the membrane origin of the vesicles on the continuous sucrose gradients. Activities of bafilomycin A1-sensitive V-type H+-ATPase (to identify vacuolar membranes), latent inosine 5′-diphosphate (IDP)ase (Golgi marker), and antimycin A-insensitive NADH cytochrome c (Cyt c) reductase (ER marker) were all determined as previously described (31–33). An extinction coefficient for Cyt c of 28 mM⋅cm−1 was used. Glucan synthase II (plasma membrane marker) was determined by using a modified protocol based on a reported method (34). Membrane vesicles (1–5 μg of protein) were resuspended in 100 μl of 330 mM sucrose, 50 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.25), 0.2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM DTT, 20 mM cellobiose, 0.2 mM spermine, 0.006% (wt/vol) digitonin, 2 mM UDP-glucose containing 0.46 kBq UDP-[14C]glucose (original specific activity 11 GBq/mmol). Enzymatic activity was stopped after 20 min incubation at 25°C by boiling for 3 min. Samples were spotted onto filter paper, dried, and subsequently washed three times for 45 min each in 0.5 M ammonium acetate (pH 3.6) and 30% (vol/vol) ethanol. Filters were dried overnight, and incorporation of UDP-[14C]glucose was determined by scintillation counting.

Ca2+ Transport Assay.

Membrane vesicles (50 μg of protein) were resuspended in 500 μl of calcium transport buffer (400 mM glycerol/5 mM bis-Tris propane-Mes, pH 7.4/25 mM KCl/3 mM MgSO4/3 mM bis-Tris propane-ATP/0.3 mM NaN3). Ca2+ uptake into and release from the vesicles was monitored with a radiometric filtration assay as described (26). Radioactivity remaining on filters after the addition of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (10 μM) was defined as nonaccumulated Ca2+ and was subtracted from all data. Typically, nonaccumulated Ca2+ amounted to 20% of total radioactivity.

Results

NAADP-Induced Ca2+ Release from Beet Microsomes.

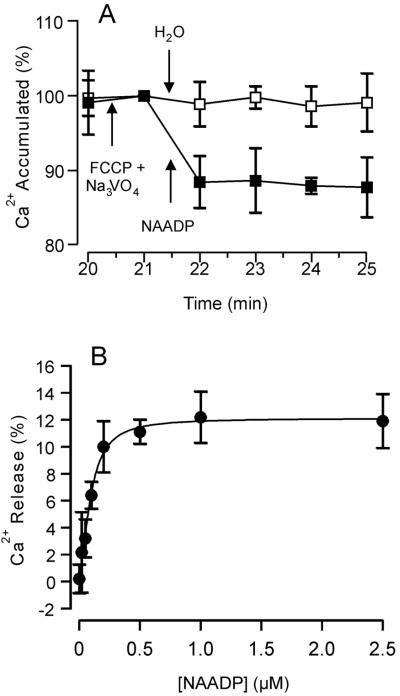

Microsomes prepared from the storage root of beet have been used previously to study Ca2+ mobilization by InsP3 and cADPR (3, 35). We used the same experimental system to examine the possibility that NAADP-activated Ca2+ mobilization occurs in plant cells. Microsomes were loaded with Ca2+ by ATP-dependent pumping. Once vesicular Ca2+ reached steady-state levels (20 min of incubation) further uptake was blocked by the addition of carbonyl cyanide ptrifluoro-methoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) and Na3VO4, inhibitors of Ca2+/H+ antiport and Ca2+-ATPases, respectively. Vesicular Ca2+ at this point, referred to as 100%, was stable for the duration of assay (Fig. 1). Addition of NAADP (1 μM) resulted in significant Ca2+ release amounting to 11.9 ± 2.3% of the total Ca2+ loaded (Fig. 1A). NAADP (0.02–2 μM) released Ca2+ from red beet microsomes in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Fitting the data with the Michaelis–Menten equation yielded a K1/2 of 96 ± 11 nM and a maximal release (Rmax) of 12.1% of the accumulated Ca2+. The K1/2 measured in this plant system is comparable to but slightly higher than that for NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release in sea urchin homogenate (K1/2 = 30 nM) (9).

Figure 1.

NAADP-elicited Ca2+ release from red beet microsomes is dose-dependent. Microsomal vesicles were loaded with Ca2+ by ATP-dependent pumping until a steady intravesicular level of Ca2+ was reached (20 min). The potential for reloading after Ca2+ release was terminated by the addition of the uncoupler FCCP (10 μM) and the P-type ATPase inhibitor Na3VO4 (200 μM). Data are standardized to this point [100% Ca2+ accumulation = 9.9 ± 0.4 nmol of Ca2+ per mg]. (A) Either NAADP (1 μM) (■) or H2O (□) was added to Ca2+-loaded vesicles. (B) Dose-dependence, with NAADP added in equal volumes to reach final concentrations of 0.02–2 μM. Data are the means ± SEM of three replicates from two preparations.

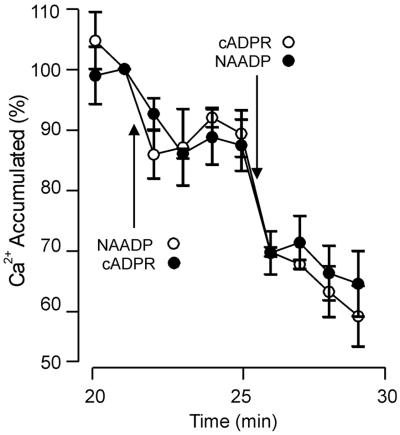

The two Ca2+-mobilizing agents cADPR and NAADP, although structurally related (36) and produced by the same ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity (37), trigger Ca2+ release through independent mechanisms in sea urchin eggs (9, 12). To ascertain whether the NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release pathway is distinct from that activated by cADPR in plant cells, Ca2+-loaded beet microsomes were treated with saturating doses (1 μM) of cADPR and subsequently NAADP. Sequential application of these ligands resulted in an additive release of Ca2+, suggesting that the two agonists act independently on Ca2+ release (Fig. 2). However, these data do not necessarily indicate that the NAADP- and cADPR-sensitive Ca2+ pathways are located on different membranes, because membrane fragmentation during isolation can yield vesicles containing a single channel type. To determine whether the Ca2+ pool(s) on which NAADP acts coreside on the vacuolar membrane with those sensitive to InsP3 and cADPR (3), Ca2+-loaded sucrose step-gradient-purified red beet vacuolar vesicles were challenged with a saturating (1 μM) dose of NAADP. Surprisingly, NAADP induced no significant Ca2+ release from the vacuolar vesicles, even though the same Ca2+-loaded vacuolar vesicles were still sensitive to InsP3 and cADPR (data not shown). This finding indicates that the site of action of NAADP is at a membrane distinct from the vacuolar membrane.

Figure 2.

Additive Ca2+ release from red beet microsomes by cADPR and NAADP. Red beet microsomal vesicles were loaded with Ca2+ for 20 min, and potential reloading after Ca2+ release subsequently inhibited as described in the legend to Fig. 1 [100% Ca2+ accumulation = 7.4 ± 0.9 nmol of Ca2+ per mg]. Ca2+ release from red beet microsomal vesicles was initiated by addition of 1 μM cADPR, then 1 μM NAADP (●) or these ligands were added in reverse order (○). Data are the means ± SEM of six (●) or nine (○) replicates from three preparations.

Distribution of NAADP-Sensitive Ca2 + Pools in Cauliflower.

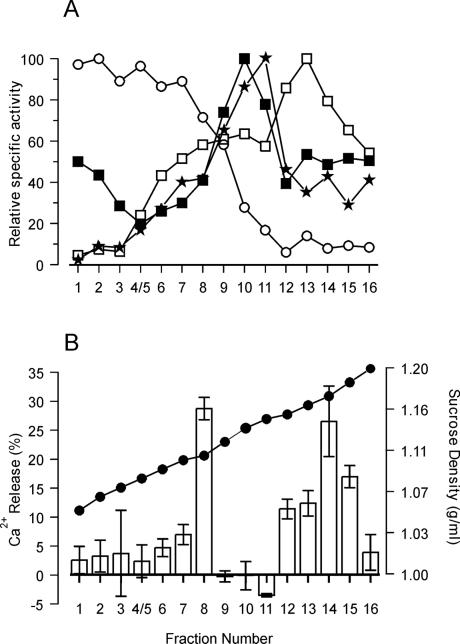

As a more convenient source of membranes to define the cellular location of NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ pools, Brassica oleracea florets were used. The uppermost region of the cauliflower inflorescences consists of cells that are mainly meristematic in nature and contain extensive ER but relatively little vacuolar membrane (38). Microsomes from this source released 15 ± 3% of accumulated Ca2+ within the first 90 s of application of 1 μM NAADP. The nonphosphorylated analog NAAD (1 μM) failed to release Ca2+, whereas in response to 1 μM NADP, 9 ± 4% of accumulated Ca2+ was mobilized during the first 90 s. This limited release of Ca2+ by NADP has been characterized in sea urchin homogenates and has been shown to result from the contamination of commercial preparations of NADP with NAADP (36, 39). The membrane identity of the Ca2+-pools sensitive to NAADP was investigated by using microsomal vesicles that had been separated on 10–45% (wt/wt) linear sucrose gradients. The protein elution profile (data not shown) revealed that the majority of protein eluted at a buoyant density of 1.16 g/ml, which closely mirrored previously reported results (26). Analysis of membrane-associated marker enzyme distribution (Fig. 3) showed that vacuolar membranes, identified by bafilomycin A1-sensitive H+-ATPase activity, resided in fractions 1–7 in the low-density region of the gradient (1.05–1.10 g/ml). Golgi-derived membranes, identified by latent IDPase activity, were in fractions 9–11 (1.12–1.15 g/ml). The peak of glucan synthase II (plasma membrane marker) activity was measured at a density of 1.15 g/ml (fraction 11). The peak of the ER marker antimycin A-insensitive NADH Cyt c reductase was in fraction 13 (1.16 g/ml), although a smaller broad peak also was observed in fractions 8–9 (1.11–1.12 g/ml). Muir and Sanders (26) described a major peak at a buoyant density of 1.12 g/ml and more diffuse activity at buoyant densities of around 1.13–1.20 g/ml. The two peaks are likely to represent two forms of ER membranes: smooth ER, characteristically found at 1.12 g/ml, and rough ER, found at a higher density, typically 1.13–1.18 g/ml, because of the presence of attached ribosomes (40).

Figure 3.

NAADP-induced Ca2+ release from cauliflower microsomal vesicles separated on continuous sucrose gradients. Freshly prepared cauliflower microsomal vesicles were separated on 10–45% (wt/wt) linear sucrose gradients. (A) Distribution of membrane marker enzyme specific activities. (○), V-type (bafilomycin A1-sensitive) H+-ATPase (100% = 31.2 μmol/mg per h); (■), latent IDPase (100% = 13.02 μmol/mg per h); (★), glucan synthase II (100% = 12.7 × 104 dpm/mg per h); (□), antimycin A-insensitive NADH-Cyt c reductase (100% = 6.03 μmol/mg per h). (B) (●), Sucrose percentage (wt/wt) of the fractions collected from the top to the bottom of the gradients. Vesicles (50 μg of protein) from each fraction were incubated for 60 min in 500 μl of Ca2+ uptake medium to obtain steady-state Ca2+ levels. The potential for reloading after Ca2+ release was prevented by the addition of FCCP (10 μM) and Na3VO4 (200 μM). NAADP (1 μM) subsequently was added and the change in accumulated Ca2+, shown as bars, was measured by the analysis of radioactivity content in aliquots removed 1 and 2 min after the addition of NAADP. Results are the means ± SEM of three experiments.

All sucrose gradient fractions were capable of accumulating Ca2+ in the presence of 3 mM Mg-ATP and vesicular steady-state Ca2+ levels were reached after 60 min of incubation (data not shown). Vesicles from each fraction then were challenged with 1 μM NAADP. Fig. 3B shows that NAADP was effective in releasing Ca2+ from fraction 8 (buoyant density, 1.11 g/ml) and fractions 12–15 (1.16–1.18 g/ml). The magnitude of Ca2+ release ranged from 11 to 28% of the total accumulated A23187-sensitive Ca2+. This finding corresponds to 1.5–5.3 nmol of Ca2+ per mg of protein. Importantly, no significant release of Ca2+ (<5% of the total A23187-sensitive Ca2+ uptake) was observed in the lighter-density fractions (1.05–1.10 g/ml) corresponding to vacuolar membranes, confirming the results obtained in beet. The first population of NAADP-sensitive vesicles (fraction 8), although residing in the lighter-density zone of the gradient (1.11 g/ml) is unlikely to be vacuolar in origin and is most likely to correspond to smooth ER. The second population of NAADP-sensitive membranes coincided with the main peak of activity of antimycin A-insensitive NADH-Cyt c reductase (Fig. 3A) and therefore is most likely representative of rough ER. Participation of Golgi and plasma membranes in NAADP-induced Ca2+ release seems to be negligible because no Ca2+ release in response to NAADP was observed in fractions 10 and 11, which correspond to the peak of latent IDPase and glucan synthase II activities, respectively.

However, because the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ pool has been suggested to be in close proximity to the plasma membrane in sea urchin eggs (41), we investigated the possible contribution of the plasma membrane to NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release in cauliflower. Cauliflower microsomes were subjected to aqueous two-phase partitioning to obtain plasma membrane vesicles of higher purity than is possible by using methods based on sucrose gradients. Enrichment of plasma membrane was confirmed by marker enzyme analysis (Table 1), which indicated a 4-fold increase of the glucan synthase II specific activity in the upper phase as compared with microsomes. Concomitantly, antimycin A-insensitive NADH-Cyt c reductase activity was found to be reduced more than 8-fold in comparison with the microsomal fraction, suggesting a strong depletion of ER in the upper phase. Levels of plasma membrane and ER marker enzyme activity in the lower phase were not significantly different as compared with the original microsomes.

Table 1.

Distribution of marker enzyme-specific activities between the upper and lower phases from aqueous two-phase partitioning of cauliflower microsomes

| Membrane fraction | Protein, mg | Glucan synthase II, dpm × 103/mg per min | Antimycin A-insensitive NADH Cyt c reductase, nmol/mg per min |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microsomes | 25 | 9.5 | 76.8 |

| Upper phase | 2.8 | 38.1 | 9.0 |

| Lower phase | 14.6 | 7.4 | 69.0 |

The data are representative of two separate membrane preparations.

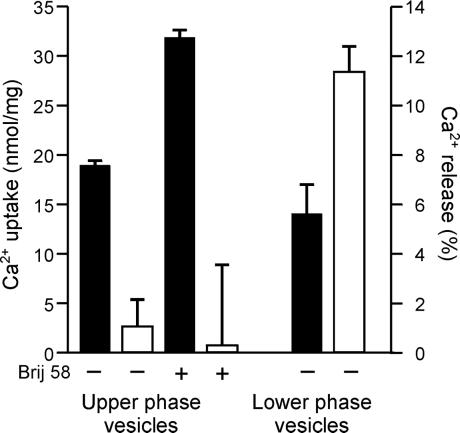

Freeze-thawed upper-phase membranes containing 40–50% cytoplasmic side-out vesicles (42) accumulated Ca2+ in an ATP-dependent manner (18.8 ± 0.6 nmol of Ca2+ per mg). On treatment with NAADP, no significant Ca2+ release was observed (Fig. 4). Addition of a very low concentration of the detergent Brij 58, which generates 100% inside-out plasma membrane vesicles (42), resulted in a 70% increase of accumulated Ca2+. However, no increase in sensitivity to NAADP was observed. In marked contrast, the lower phase, which contains the bulk of the intracellular membranes, was found to respond to NAADP by releasing 11.4 ± 1.1% of the accumulated Ca2+ (Fig. 4). Calcium could still be mobilized from the upper phase by imposing a 60 mV K+ diffusion potential on addition of valinomycin to membranes with 25 mM K+ inside and 2.5 mM K+ outside the vesicles (data not shown), demonstrating the viability of the upper-phase vesicles to release Ca2 + via a voltage-dependent pathway (43). These data indicate that the plasma membrane plays no role in NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release.

Figure 4.

Ca2+ uptake and NAADP-sensitivity of cauliflower vesicles separated by aqueous two-phase partitioning. Vesicles (100 μg/ml) from the upper and lower phases obtained after aqueous two phase-partition of cauliflower microsomes were loaded with Ca2+ for 60 min in the absence (−) or presence (+) of Brij 58 (0.05% wt/vol), as shown. The potential for reloading after Ca2+ release was abolished by the addition of FCCP (10 μM) and Na3VO4 (200 μM). Levels of Ca2+ uptake (expressed as nmol of Ca2+ per mg) are indicated by the black bars. Subsequently, NAADP (1 μM) was added, and three aliquots from each preparation were removed to estimate Ca2+ remaining in the vesicles by measuring radioactive content. Magnitude of Ca2+ release (expressed as percentage of the total accumulated Ca2+) is indicated by the white bars. Data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples from three independent experiments; for clarity, only the positive SEM is shown.

NAADP Production by Tissue Homogenates.

To determine whether cauliflower inflorescences are competent in NAADP synthesis, tissue homogenate was incubated with the precursors NADP and nicotinic acid for 0 to 3 h. In the absence of precursors, a basal level of 125 pmol/mg of protein was detected by using the sea urchin microsome desensitization assay (29). In the presence of the precursors, NAADP was synthesized at a rate of 6.5 pmol/mg per min (linear for 20 min).

Pharmacology of NAADP-Dependent Ca2+ Release.

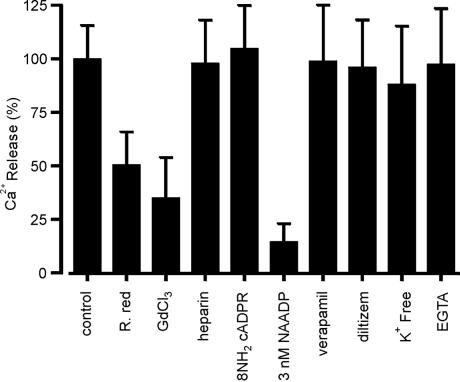

Cauliflower membrane vesicles collected at 1.17 g/ml buoyant density from the linear sucrose gradient (fraction 14 in Fig. 3) were further characterized with respect to the pharmacological properties of NAADP-gated Ca2+ release. The sensitivity of NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release to the nonspecific Ca2+ channel blockers Gd3+ and ruthenium red was tested. Gd inhibits Ca2+ channels in animals and plants (44, 45), and ruthenium red inhibits cADPR-induced Ca2+ release in plant cells (3) as well as several classes of plant plasma membrane Ca2+ channel (43). We observed a 70% and 50% reduction of the Ca2+ release induced by NAADP in the presence of Gd3+ and ruthenium red, respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Pharmacology of NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release. Cauliflower membrane vesicles sampled at 1.17 g/ml equilibrium density in sucrose were incubated for 60 min in 500 μl of Ca2+ uptake medium to obtain steady-state Ca2+ levels. Potential reloading after Ca2+ release was prevented by addition of FCCP (10 μM) and Na3VO4 (200 μM) (100% = 8.4 ± 0.3 nmol of Ca2+ per mg). The following subsequently were imposed: 8-NH2-cADPR (2.5 μM), low-molecular weight heparin (10 μM), NAADP (3 nM), verapamil (50 μM), diltiazem (50 μM), GdCl3 (100 μM), ruthenium red (30 μM), or EGTA (150 μM). After 1 min of pretreatment, the vesicles were challenged with NAADP (1 μM). For assays performed in K+-free reaction medium, the loading medium also was K+-free. Results are the means ± SEM of three experiments.

A more detailed investigation into the NAADP-induced Ca2+ release was instigated by using the specific inhibitors of the cADPR- and InsP3-gated Ca2+ release pathways 8-NH2-cADPR (46) and heparin (47, 48). These antagonists had no effect on NAADP-induced Ca2+ release (Fig. 5), reinforcing the hypothesis that NAADP acts on a separate and distinct Ca2+-releasing pathway to those previously reported in plants. In sea urchin eggs, NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release displays a unique inactivation phenomenon, namely low nanomolar concentrations (≤3 nM) of NAADP, which are subthreshold with respect to Ca2+ release, fully inactivate subsequent Ca2+ release by a normally permissive dose of NAADP (16, 17). We observed a similar inhibition of NAADP-elicited Ca2+ release when the ligand was added at a saturating concentration (1 μM) to Ca2+-loaded cauliflower membrane vesicles pretreated with 3 nM NAADP (Fig. 5). The addition of 3 nM NAADP itself caused no change in vesicular Ca2+ levels (data not shown).

In sea urchin eggs, L-type Ca2+ channel blockers (15, 16) were found to inhibit fully Ca2+ release by NAADP, suggesting similarities between these two classes of Ca2+ channel (15). However, we found that two L-type channel blockers, diltiazem and verapamil, had no effect on Ca2+ release by NAADP (Fig. 5). These compounds also have been shown to have no effect on plant plasma membrane Ca2+ channels (44).

It has been suggested that K+, either as a counter ion or as a cofactor, is a requirement for InsP3-induced Ca2+ release (49), whereas NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release pathways seem to be independent of the presence of monovalent cations (15). In the absence of K+ on the cytosolic side, NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release from cauliflower membrane vesicles exhibits no requirement for monovalent cations such as K+ (Fig. 5). NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release also has been shown to be independent of [Ca2+]c (0–100 μM) (14). In this study, a decrease in [Ca2+]c from 10 μM to 5 nM by the addition of EGTA (150 μM) did not significantly affect the Ca2+ release by NAADP. This result indicates that [Ca2+]c does not play a role in NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release and suggests, as in animal systems, that this pathway plays no role in Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release.

Discussion

Microsomes derived from cauliflower and beet previously have been described as sensitive to the Ca2+-mobilizing ligands InsP3 and cADPR (3, 26, 35). In this study, we demonstrate release by a third Ca2+-mobilizing agent, the NADP-derived metabolite NAADP. Ca2+ release induced by NAADP is dose-dependent with a K1/2 in the nanomolar range (96 nM) similar to that observed in animal species (39). Specific antagonists of cADPR- and InsP3-gated Ca2+ release pathways fail to block NAADP-induced Ca2+ release from both beet and cauliflower microsomes, indicating that the NAADP-sensitive pathway is distinct from the other two.

Detection of NAADP in cauliflower inflorescences was achieved by using a desensitization bioassay. Furthermore, the tissue possesses the metabolic machinery to synthesize NAADP from its precursors NADP and nicotinic acid. The rate of NAADP production (6.5 pmol/mg per min) is of the same order, albeit slightly slower, as has been reported in similar conditions for sea urchin and whole brain extracts (11, 29).

The inactivation of NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release by a nonreleasing dose of NAADP (3 nM) in cauliflower vesicles indicates that spontaneous desensitization is conserved across taxonomically diverse groups (cf. refs. 15 and 16). Other pharmacological properties of the sea urchin NAADP-induced Ca2+ release pathway seem not to be as well conserved in plants: The lack of effect of diltiazem and verapamil indicates that the NAADP-mediated Ca2+-release pathway in plants has regulatory and structural differences from that in sea urchins (15).

Previous demonstrations of both cADPR- and InsP3-elicited Ca2+ release at the vacuolar membrane of red beet (3) have highlighted the role of the vacuole as a major store of releasable Ca2+ in plants. Purification of vacuolar vesicles from red beet microsomes revealed, somewhat surprisingly, that the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ pool does not reside at the vacuolar membrane. In sea urchin eggs, the membrane location of the NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release pathway is still under scrutiny. Separation of sea urchin microsomes on Percoll gradients has demonstrated that the InsP3- and cADPR-dependent Ca2+ release pathways coreside in the same fraction, whereas the NAADP-sensitive vesicles are scattered throughout various fractions (39). However, the precise membrane location of the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ pool could not be defined (12, 50). It is interesting to note that the distribution of ligand-sensitive Ca2+ pools share similar patterns in both sea urchins and plants, whereby InsP3- and cADPR-gated channels coreside on the same membrane type, ER in the case of sea urchins and the vacuolar membrane in the case of plants. The possibility that InsP3- and cADPR-gated channels also reside on the ER of plants has not yet been rigorously investigated. Nevertheless, the NAADP-gated pathway clearly differs from the other two by its absence in vacuolar membranes. Cauliflower membrane fractionation showed that the majority of the NAADP-sensitive membrane vesicles (1.16–1.18 g/ml) colocalized with the peak of the ER marker enzyme activity, corresponding to rough ER. The additional presence of NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release at a buoyant density of 1.11 g/ml, in the middle of the ER marker enzyme activity attributed to smooth ER, reinforces the evidence for an ER location of the NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ pool.

The ER and plasma membrane have a close physical relationship in plant cells (51), and activity of enzymes attributed to the ER and plasma membrane partially overlap in the higher density fractions of sucrose gradients (ref. 40 and Fig. 3A). However, possible involvement of the plasma membrane in NAADP-elicited Ca2+ mobilization was excluded because plasma membrane vesicles purified by aqueous two-phase partitioning demonstrated a lack of response to NAADP. Another possible contaminating membrane type in the high-density fractions of sucrose gradients is mitochondrial membrane. Mitochondria were unlikely to participate in NAADP-elicited Ca2+ release in these experimental conditions because the mitochondrial H+-ATPase inhibitor NaN3 was always included in the Ca2+ transport assays.

This paper reports a ligand-gated Ca2+ release pathway at the ER in plants. The ER increasingly is being seen as an important Ca2+ store in plant cells (52). P-type Ca2+ ATPases, which are sensitive to Na3VO4 but insensitive to the specific blocker of animal ER-located Ca2+ ATPases, thapsigargin (53), are present at the ER membrane (54). The ER additionally contains the Ca2+-binding protein calreticulin that is thought to act, as in animal cells, as an effective Ca2+ buffer within the ER lumen (55). A voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (56) and possibly InsP3 receptors (26) exist at the ER membrane. The presence of Ca2+-release mechanisms suggests that the ER is not just a Ca2+ repository for the cell but can play an active part in Ca2+ signaling as a mobilizable Ca2+ store.

A long-standing problem in Ca2+ signaling is how, given the wide array of stimulus-response pathways in which Ca2+ is involved (1), stimulus specificity can be encoded. This information has been proposed to be encoded in the spatial and temporal components of the Ca2+ signal (9, 57). The presence of multiple, distinct pathways through which Ca2+ can be released at different intracellular locations and at least three endogenous molecules that can act as Ca2+-mobilizing agents (InsP3, cADPR, and NAADP) add an extra dimension to our current understanding of plant Ca2+ signaling specificity.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Walseth (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis) for the kind gifts of NAADP, cADPR, and 8-NH2-cADPR. We are grateful to L. Williams (University of Southampton, U.K.) and S. R. Muir (Unilever, Colworth, U.K.) for their helpful advice on membrane separation. L.N. was supported by a long-term fellowship from the European Molecular Biology Organization, and M.A.B., A.S., and G.D.D. were supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Abbreviations

- cADPR

cyclic ADP-ribose

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FCCP

carbonylcyanide p-trifluoro-methoxyphenylhydrazone

- InsP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- NAADP

nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- [Ca2+]c

cytosolic free calcium

- Cyt c

cytochrome c

- IDP

inosine 5′-diphosphate

Footnotes

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.140217897.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.140217897

References

- 1.Sanders D, Brownlee C, Harper J F. Plant Cell. 1999;11:691–706. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.4.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Y, Kuzma J, Marechal E, Graeff R, Lee H C, Foster R, Chua N H. Science. 1997;278:2126–2130. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen G J, Muir S R, Sanders D. Science. 1995;268:735–737. doi: 10.1126/science.7732384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muir S R, Sanders D. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01000-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen G J, Sanders D. Plant J. 1994;6:687–695. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coté G G, Crain R C. BioEssays. 1994;16:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berridge M J. Nature (London) 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H C. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:355–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAinsh M R, Hetherington A M. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancela J M, Churchill G C, Galione A. Nature (London) 1999;398:74–76. doi: 10.1038/18032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bak J, White P, Timar G, Missiaen L, Genazzani A A, Galione A. Curr Biol. 1999;9:751–754. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chini E N, Beers K W, Dousa T P. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3216–3223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genazzani A A, Galione A. Biochem J. 1996;315:721–725. doi: 10.1042/bj3150721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chini E N, Dousa T P. Biochem J. 1996;316:709–711. doi: 10.1042/bj3160709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genazzani A A, Mezna M, Dickey D M, Michelangeli F, Walseth T F, Galione A. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1489–1495. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genazzani A A, Empson R M, Galione A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11599–11602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aarhus R, Dickey D M, Graeff R M, Gee K R, Walseth T F, Lee H C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8513–8516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Terzic C M, Chini E N, Shen S S, Dousa T P, Clapham D E. Biochem J. 1995;312:955–959. doi: 10.1042/bj3120955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albrieux M, Lee H C, Villaz M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14566–14574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chini E N, Dousa T P. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;209:167–174. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumwald E, Poole R J. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:727–731. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.3.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giannini J L, Gildensoph L H, Reynolds-Niesman I, Briskin D P. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:1129–1136. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.4.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Askerlund P, Evans D E. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1670–1681. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.4.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Askerlund P. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:999–1007. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.3.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanders D, Muir S R, Allen G J. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:856–861. doi: 10.1042/bst0230856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muir S R, Sanders D. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:1511–1521. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.4.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumwald E, Rea P A, Poole R J. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson L J, Xing T, Hall J L, Williams L E. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:553–564. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson H L, Galione A. Biochem J. 1998;331:837–843. doi: 10.1042/bj3310837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradford M M. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sze H, Ward J M, Lai S P. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1992;24:371–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00762530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green J R. In: Isolation of Organelles from Plant Cells. Hall J L, Moore A L, editors. New York: Academic; 1983. pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodges T K, Leonard R T. Methods Enzymol. 1974;32:397–398. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)32039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ray P M. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:594–599. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.4.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muir S R, Bewell M A, Sanders D, Allen G J. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:589–597. doi: 10.1093/jxb/48.Special_Issue.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee H C. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:1133–1164. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aarhus R, Graeff R M, Dickey D M, Walseth T F, Lee H C. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30327–30333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dozolme P, Martymazars D, Clemencet M C, Marty F. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1509–1517. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H C, Aarhus R. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2152–2157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson D G, Hinz G, Oberbeck K. In: Plant Cell Biology: A Practical Approach. Harris N, Oparka K J, editors. Kingston, ON: IRC Press; 1994. pp. 245–272. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Genazzani A A, Galione A. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:108–110. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johansson F, Olbe M, Sommarin M, Larsson C. Plant J. 1995;7:165–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.07010165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White P J. Ann Bot (London) 1998;81:173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang X C, Sachs F. Science. 1989;243:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.2466333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johannes E, Brosnan J M, Sanders D. Plant J. 1992;2:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walseth T F, Lee H C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1178:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90199-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehrlich B E, Kaftan E, Bezprozvannay S, Bezprozvanny I. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brosnan J M, Sanders D. FEBS Lett. 1990;260:70–72. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mezna M, Michelangeli F. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28097–28102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clapper D L, Walseth T F, Dargie P J, Lee H C. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9561–9568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hepler P K, Palevitz B A, Lancelle S A, McCauley M M, Lichtscheidl I. J Cell Sci. 1990;96:355–373. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bush D S. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:95–122. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomson L J, Hall J L, Williams L E. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1295–1300. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harper J F, Hong B M, Hwang I D, Guo H Q, Stoddard R, Huang J F, Palmgren M G, Sze H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1099–1106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Navazio L, Sponga L, Dainese P, Fitchette-Lainé A C, Faye L, Baldan B, Mariani P. Plant Sci. 1998;131:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klüsener B, Boheim G, Liss H, Engelberth J, Weiler E W. EMBO J. 1995;14:2708–2714. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berridge M J. Nature (London) 1997;386:759–760. doi: 10.1038/386759a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]