Abstract

Diffuse iris melanoma is an uncommon variant of anterior uveal melanoma. It is characterized by heterochromia and unilateral glaucoma secondary to angle invasion, and can be difficult to diagnose. We present a patient who had been managed for left-sided raised intraocular pressure with latanoprost eye drops for 12-months and pigmentary changes were subsequently noted. On referral to the Ocular Oncology Unit, Sydney, iris melanoma was suspected and confirmed on iridectomy, and the eye was eventually enucleated.

Keywords: iris, diffuse melanoma, glaucoma, latanoprost, cytogenetics

Introduction

Iris melanoma is a rare tumor representing 2%–3% of all uveal melanoma, and the diffuse variant accounts for 10% of cases (Demirci et al 2002). It typically presents with darkening of the iris or blurred vision, and is characterized by unilateral glaucoma and heterochromia. The tumor arises from malignant transformation of an iris stromal melanocyte, and spreads throughout the iris to invade the angle and extraocular tissues.

Case report

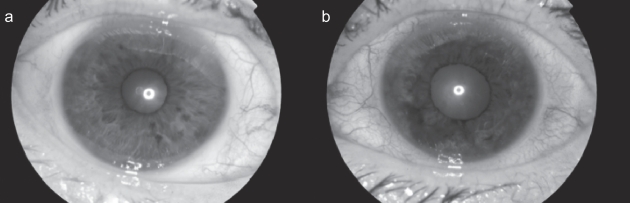

A 70-year old man was referred to the Sydney Ocular Oncology Unit for evaluation of refractory left sided glaucoma and iris heterochromia (Figure 1). 12-months previously he had presented elsewhere with raised left intraocular pressure, associated with asymmetrical disc cupping, open angles on gonioscopy and some early left nasal changes on perimetry. The diagnosis of glaucoma was made and timolol and latanoprost eye drops were started. After 9-months of treatment pigmentary changes in the left iris were observed and thought to be related to latanoprost. On subsequent evaluation malignant heterochromia was suspected and he was referred to the Unit.

Figure 1.

Right and left eyes on presentation. (a) OD. Normal iris. (b) OS. There is an irregular pigmented lesion with loss of iris architecture associated with ciliary injection.

Ophthalmic examination revealed a visual acuity of 6/7.5 OD and 6/7.5 OS, right and left intra ocular pressure (IOP) of 10 and 18 mmHg, and a sluggish left pupillary reflex. On slit-lamp examination there was ciliary injection and a diffuse pigmented iris lesion with irregular surface protrusions and loss of architectural integrity (Figure 1). The anterior chamber, lens and media were clear and left glaucomatous optic disc atrophy was seen. Gonioscopy showed angle invasion with outflow obstruction between clock-hours 4 and 11.

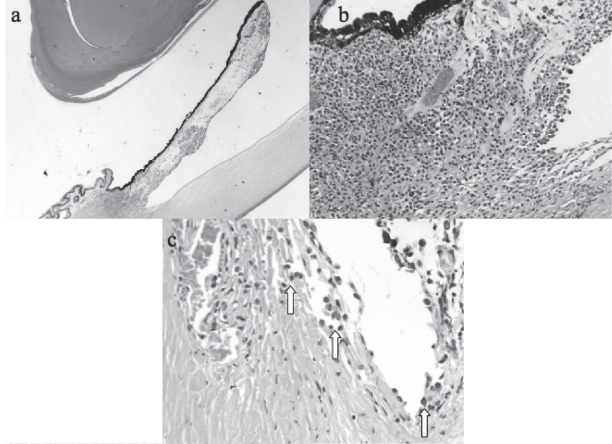

Ultrasound biomicroscopy was performed, which confirmed an irregular iris surface and demonstrated some thickening of segments of the iris root. CT head, chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no evidence of metastatic disease, and blood tests were normal. A left-temporal iridectomy through clear cornea was performed which revealed an iris melanoma. Because of diffuse angle involvement and refractory glaucoma, enucleation was performed and no extraocular extension was detected. Histopathology demonstrated a diffuse iris melanoma with predominant epithelioid cell morphology (Figure 2). Fluorescence in situ hybridization on the paraffin-embedded specimen revealed a single pattern of loss of a chromosome 3 locus but no gain of chromosome 8.

Figure 2.

Enucleated left eye (hematoxylin and eosin). (a) Melanoma diffusely spread throughout the iris and invading the ciliary body (×10). (b) Iris root and corneal endothelial invasion by epithelioid melanoma cells (×60). (c) Tumor cells (arrows) seeding the trabecular meshwork (×80).

Discussion

Diffuse iris melanoma can be challenging to diagnose, and a high degree of suspicion is necessary in patients presenting with pigmentary change and unilateral glaucoma. Patients can receive medical or surgical treatment for glaucoma before the tumor is detected (Demirci et al 2002).

In this case topical latanoprost obscured a malignant cause for heterochromia. Latanoprost has been compared to other commercially available prostaglandin analogues, and all cause a similar degree of iris pigmentary changes (Li et al 2006). With increasing use of topical prostaglandins, heterochromia and glaucoma are not uncommon (Alm and Stjernschantz 1995); however, findings on slit-lamp were suggestive of malignancy. Concern about the oncogenic potential of topical prostaglandins has been raised previously; however, subsequent laboratory and clinical studies have not demonstrated any relationship of this kind (Dutkiewicz et al 2000). In this case an etiological link between latanoprost and malignancy is unlikely given the brief interval between exposure and clinical melanoma; however, benign melanosis is noted in the pigment epithelial layer of the iris (Figure 2).

The mechanisms responsible for glaucoma caused by iris melanoma were investigated by Shields et al in a series of 169 patients. A diffuse configuration, angle invasion with tumor seeds, peripherally based tumors and increasing tumor size predicted raised IOP (Shields, Materin et al 2001). In this case raised IOP was due to trabecular meshwork and angle invasion, which was associated with a poor visual prognosis. Although this is more commonly a feature of ring melanoma of the ciliary body (Demirci et al 2001), there was not enough contiguous ciliary body involvement to suggest a ring melanoma (Figure 2).

Raised IOP can be medically managed with beta blockers, alpha-2 agonists and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Latanoprost, which upregulates matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) and thereby reduces resistance to uveoscleral flow may theoretically increase the risk of extraocular dissemination of tumor cells through the same pathway. Given that MMPs are found in the sclera as well, latanoprost may affect scleral collagen and improve trans-scleral flow, however there is no evidence that cellular material can pass through this route. Drainage surgery, such as trabeculectomy or shunt procedures, is definitely contraindicated as it may facilitate extraocular tumor spread, and such procedures are often responsible for cases of metastasis (Girkin et al 2002).

A large proportion of iris melanomas will not grow and lesions less than 3 mm can be treated conservatively with initial trial of observation (Conway et al 2001). Any suspicious lesion warrants histological diagnosis with either fine needle aspirate or iridectomy/iridocyclectomy. Under hypotensive general anesthesia, the latter involves a 90% thickness posteriorly-hinged scleral flap to 2–3 mm on either side of the tumor, followed by a large lamellar flap splitting the corneal stroma overlying the tumor and subsequent removal. These techniques minimize the risk of incomplete excision and dissemination of malignant cells (Char et al 2001; Conway et al 2001). While local surgical removal is used to treat most iris melanomas, it is contraindicated in the presence of raised intraocular pressure due to extensive angle involvement by tumor cells. Enucleation is indicated for diffusely growing melanomas, widespread angle invasion and glaucoma (Demirci et al 2002). Plaque brachytherapy can be used to control diffuse variants, but long term data is lacking (Finger 2001).

The chromosomal alterations of iris melanoma are poorly characterized. A few studies have indicated that they are distinct from those found in choroidal melanoma (Sisley et al 1998). However, monosomy in chromosome 3 is a marker of poor prognosis in posterior uveal melanoma, and may imply a similarly poor prognosis in iris melanoma (Prescher et al 1995). The cytogenetic profile of this case is difficult to interpret but may represent an aggressive tumor biology.

The 5-year metastatic rate of diffuse iris melanoma has been reported as 13% over 6-years (Demirci et al 2002), compared to 3% after 5-years for circumscribed iris melanoma (Shields CL, Shields JA et al 2001). Metastases are invariably hematogenous, with the majority going to the liver like other uveal melanomas (Millodot et al 2006). This man has been recommended biannual follow up with baseline full systemic examination, liver imaging and evaluation of blood count and liver function.

Conclusion

This case exemplifies a potential clinical problem of a prostaglandin analogue masking a malignant cause of heterochromia. Establishing the correct diagnosis of iris melanoma is essential, particularly since various treatment modalities for primary glaucoma may contribute to tumor seeding. Tissue diagnosis is required in most cases and with appropriate surgical techniques no increased risk of spreading melanoma cells at biopsy has been demonstrated (Char et al 2001). Because diffuse iris melanoma is typically found with refractory raised intraocular pressure after invasion of the angle has occurred, enucleation is a relatively common end point.

References

- Alm A, Stjernschantz J. The Scandinavian Latanoprost Study Group: effects on intraocular pressure and side effects of 0.005% latanoprost applied once daily, evening, or morning. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1743–52. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Char DH, Miller T, Crawford JB. Uveal tumour resection. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;85:1213–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.10.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway RM, Chua WC, Qureshi C, et al. Primary iris melanoma: diagnostic features and outcome of conservative surgical treatment. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;85:848–54. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Ring melanoma of the anterior chamber angle: a report of fourteen cases. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;132:336–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Diffuse iris melanoma: a report of 25 cases. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1553–60. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutkiewicz R, Albert DM, Levin LA. Effects of latanoprost on tyrosinase activity and mitotic index of cultured melanoma lines. Experimental Eye Research. 2000;70:563–9. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger PT. Plaque radiation therapy for malignant melanoma of the iris and ciliary body. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;132:328–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girkin CA, Goldberg I, Mansberger SL, et al. Management of iris melanoma with secondary glaucoma. Journal of Glaucoma. 2002;11:71–4. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Chen XM, Zhou Y, et al. Travoprost compared with other prostaglandin analogues or timolol in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2006;34:755–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millodot M, Hendler K, Pe’er J. Iris melanoma: a case report and review. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2006;26:120–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Friedrichs W, et al. Cytogenetics of twelve cases of uveal melanoma and patterns of nonrandom anomalies and isochromosome formation. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1995;80:40–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(94)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Materin MA, Shields JA, et al. Factors associated with elevated intraocular pressure in eyes with iris melanoma. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;85:666–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.6.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Shields JA, Materin M, et al. Iris melanoma: risk factors for metastasis in 169 consecutive patients. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:172–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisley K, Brand C, Parsons MA, et al. Cytogenetics of iris melanoma: disparity with other uveal tract melanomas. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1998;101:128–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]