Abstract

Statement of Translational Relevance

Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), such as rapamycin and its analogues, are currently being tested in clinical trial for TSC as well as many human cancers, which display hyperactivated mTORC1 signaling. mTORC1 has emerged as a critical integrator of signals from growth factor, nutrient, oxygen, and energy to regulate cell growth and proliferation. This study demonstrates for the first time that mTORC1 signaling is aberrantly hyperactivated in primary chordoma tumors/cell lines and PTEN deficiency may be frequently associated with sporadic chordomas. Furthermore, we show that the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin suppresses mTORC1 signaling and proliferation of chordoma-derived cell line. Therefore, this study not only reveals pathogenic mechanisms of chordomas, but also provides a rationale for initiating clinical trials of Akt/mTORC1 inhibition in patients with sporadic chordomas.

Purpose

Chordomas are rare, malignant bone neoplasms in which the pathogenic mechanisms remain unknown. Interestingly, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) is the only syndrome where the incidence of chordomas has been described. We previously reported the pathogenic role of the TSC genes in TSC-associated chordomas. In this study, we investigated whether aberrant TSC/mTORC1 signaling pathway is associated with sporadic chordomas.

Experimental Design

We assessed the status of mTORC1 signaling in primary tumors/cell lines of sacral chordomas and further examined upstream of mTORC1 signaling, including PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome ten) tumor suppressor. We also tested the efficacy of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin on signaling and growth of chordoma cell lines.

Results

Sporadic sacral chordoma tumors and cell lines examined commonly displayed hyperactivated Akt and mTORC1 signaling. Strikingly, expression of PTEN, a negative regulator of mTORC1 signaling, was not detected or significantly reduced in chordoma-derived cell lines and primary tumors. Furthermore, rapamycin inhibited mTORC1 activation and suppressed proliferation of chordoma-derived cell line.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that loss of PTEN as well as other genetic alterations which result in constitutive activation of Akt/mTORC1 signaling may contribute to the development of sporadic chordomas. More importantly, a combination of Akt and mTORC1 inhibition may provide clinical benefits to chordoma patients.

Keywords: chordomas, tuberous sclerosis complex, mTOR, PTEN, Akt

Introduction

Chordomas are uncommon, slow growing, malignant neoplasms, which are thought to originate from notochordal remnants along the axial skeleton in the sacrococcygeal/sacral, sphenooccipital/clivus, and spinal regions (1). Chordomas are usually sporadic, but a few families have been reported with multiple family members affected by chordoma (2–6), suggesting that inherited variations may predispose to these tumors. Intriguingly, several investigations identified chordomas in TSC patients (7–11). We previously reported two cases of TSC with concomitant sacrococcygeal chordomas and identified somatic inactivation of the TSC genes, thus providing the first evidence of a pathogenic role of the TSC genes in sacrococcygeal chordomas (12).

TSC is a tumor suppressor syndrome characterized by abnormal tissue growths, known as hamartomas, in many organs (13). TSC is caused by inactivating mutations in tumor suppressor genes TSC1 or TSC2, which encode hamartin (TSC1) and tuberin (TSC2), respectively. Of note, somatic mutations in these genes are also found in sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) (14, 15). TSC proteins form a heterodimeric TSC1-TSC2 complex and function to inhibit mTORC1 signaling, which critically regulates cell growth and proliferation (16, 17). Activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt or Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by growth factors leads to TSC2 phosphorylation and inhibition of the TSC protein complex by Akt, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p90 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (RSK1) kinases (Fig. 1A). Another important negative regulator of Akt/mTOR pathway is PTEN, a lipid phosphatase that decreases the effective concentration of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) in cells. In cells lacking TSC1, TSC2, or PTEN, mTORC1 is hyperactivated resulting in constitutive phosphorylation of S6K, S6 and 4EBP1, which is potently inhibited by the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. Importantly, the TSC/mTORC1 pathway is dysregulated in several hamartoma syndromes as well as in many cancers (16–18).

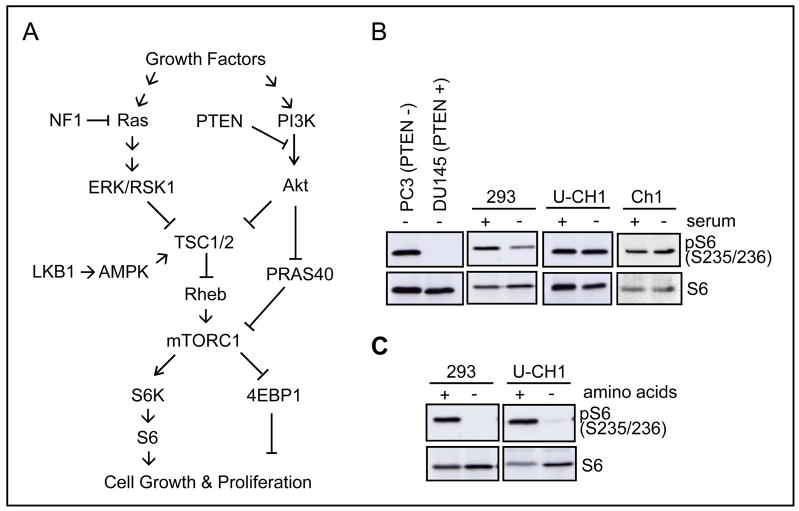

Figure 1.

Hyperactivated mTORC1 signaling in U-CH1 cells. A, PI3K/Akt/TSC/mTORC1 pathway in control of cell growth and proliferation. Activated Akt/ERK/RSK1 kinases upon growth factor stimulation or loss of PTEN or NF1 mediate inactivation of TSC complex and subsequent increase in Rheb activity, which in turn result in mTORC1 activation and phosphorylation of S6K, S6, and 4EBP1 proteins to promote protein synthesis. Akt also inhibits PRAS40, which negatively regulates mTORC1 signaling. In low energy condition, LKB1 phosphorylates AMPK to stabilize and activate TSC1/2 activity. B, growth factor-independent phosphorylation of S6 in serum-starved U-CH1 cells. Cells were grown in the absence or presence of 10% FBS for 20 hr and then harvested for western analysis. C, termination of S6 phosphorylation upon amino acid depletion. U-CH1 and 293 cells were cultured in the absence of serum for 20 hr (+ amino acid) and then incubated with Dulbecco’s PBS (D-PBS) containing glucose and pyruvate for 1 hr (− amino acid).

Based on the roles of the TSC genes in the pathogenesis of TSC-associated chordomas, we hypothesized that dysregulation in the TSC/mTORC1 pathway may be associated with sporadic chordoma. Here, we show that aberrant hyperactivation of Akt/mTORC1 pathway is commonly found in sporadic sacrococcygeal chordomas, and rapamycin treatment strongly inhibits mTOR activation and proliferation of chordoma-derived U-CH1 cells. In addition, we have observed either reduced or lack of expression of PTEN in many of the sporadic sacral chordomas examined, which may explain the activation of Akt/mTORC1 signaling. These findings suggest the potential efficacy of Akt/mTOR inhibitors as a possible therapeutic approach for this malignant tumor.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Ten cases of sporadic chordoma and one case of TSC-associated chordoma tumors were available through the Department of Pathology at Massachusetts General Hospital under the approval of Institutional Review Board.

Cell culture, antibodies, and reagents

The human sacrococcygeal chordoma-derived U-CH1 cell line was maintained as described with minor modification (19). U-CH1 cells were grown in plates coated with 0.005% collagen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a 4:1 mixture of IMDM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and RPMI-1640 (Sigma) media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Human prostate tumor cell lines PC3 and DU145, human embryonic kidney 293, and human chordoma-derived Ch1 cell lines were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. All antibodies used in this study, except for anti-TSC2 (20), anti-GAPDH (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and anti-pPRAS40 (Invitrogen), were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Wortmannin and DMSO (Sigma), rapamycin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), and Dulbecco’s PBS (D-PBS, Invitrogen) containing glucose and pyruvate were also utilized.

Western analysis

Preparation of cell lysates and western analysis were performed as described previously (20).

Immunohistochemistry

Human tissues were fixed in formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin.

Immunohistochemistry was carried out using anti-PTEN (1:100), anti-pPRAS40 (T246, 1:750), anti-pS6 (S240/244, 1:100), and anti-p4EBP1 (T37/46, 1:100) antibodies, employing methods described earlier (21).

Proliferation assay of U-CH1 cells

At day 0, U-CH1 cells were plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in a 24-well plate. Each experimental group was carried out in triplicate. At days 1, 3, 5, and 7, cells were fed with fresh growth media containing vehicle DMSO (0.1%) or rapamycin (1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 nM). At days 3, 6, and 9, cells were collected by trypsin treatment, and cell numbers were determined using a hemacytometer.

For 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation to detect S-phase cells, U-CH1 cells were plated in collagen-coated coverslips, treated with DMSO or varying concentration of rapamycin as described above, incubated with 10 μM BrdU for the final 24 hr. BrdU incorporation was detected using a fluorescein-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody in In Situ Cell Proliferation Kit, FLUOS (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). BrdU-positive cells were counted in 5 randomly chosen fields per condition using a TCS SP5 confocal microscopy (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and the percentage of BrdU-positive cells were calculated.

Statistical analysis

For comparisons of cell numbers in vehicle versus rapamycin-treated groups, a paired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used.

Results

mTORC1 signaling is activated in U-CH1 cells

We first examined mTORC1 signaling in the sacral chordoma-derived U-CH1 cell line, which has nearly identical immunohistochemical, morphological, and cytogenetic aberrations found in its parental primary sacral tumor (19). We tested whether mTORC1 signaling in U-CH1 cells is constitutively active in the absence of growth factors or amino acids, by monitoring the level of phosphorylated S6 (Ser235/236) which serves as a readout for mTORC1 signaling. The human prostate tumor-derived, PTEN-negative PC3 and PTEN-positive DU145 cells were employed as positive and negative controls for mTORC1 signaling, respectively (21, 22). S6 phosphorylation in both U-CH1 and another chordoma-derived Ch1 cell lines was persistently elevated, even under serum-starved conditions, in the same way as in PC3 cells, whereas S6 phosphorylation was significantly reduced in serum-starved 293 and DU145 cells (Fig. 1B). In contrast to serum deprivation, amino acid depletion for 1 hr resulted in complete termination of S6 phosphorylation in U-CH1 cells, which was also observed in amino acid-starved 293 cells (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that mTORC1 signaling in chordoma-derived cell lines is deregulated in response to growth factor deprivation, but remains sensitive to amino acid availability.

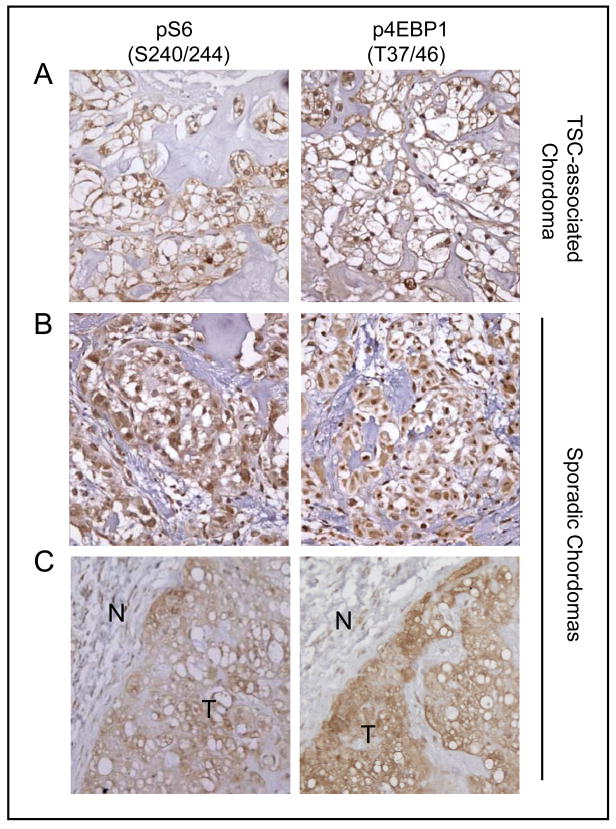

mTORC1 signaling is abnormally hyperactivated in sporadic chordomas

We next examined mTORC1 signaling in 10 sporadic sacral chordoma tumors and one TSC-associated chordoma by immunohistochemical staining to detect the levels of pS6 (S240/244) and p4EBP1 (T37/46) proteins, which serve as readouts for mTORC1 signaling. Previously, we reported that TSC-associated angiomyolipomas, tubers, and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas displayed highly elevated levels of mTORC1 signaling (21). Consistent with these results, the TSC-associated chordoma stained strongly positive for pS6 (S240/244) (Fig. 2A). Strikingly, all 10 sacral chordomas examined in this study also exhibited varying degrees of positivity for pS6 (S240/244), compared to non-neoplastic neighboring normal cells (Fig. 2B, C and Table 1). Furthermore, all the tumors also showed high immunoreactivity to p4EBP1 (T37/46) antibody (Fig. 2 and Table 1). These results indicate that mTORC1 signaling is hyperactivated in sporadic sacral chordomas.

Figure 2.

Elevated levels of pS6 and p4EBP1 in sporadic chordomas and a TSC-associated chordoma. Representative images of a TSC-associated chordoma (A) and two examples of sporadic chordomas (B and C) showing strong immunoreactivity to anti-pS6 (S240/244) and anti-p4EBP1 (T37/46) antibodies. N, non-neoplastic normal cells; T, tumor. Magnification: X 400 (A and B); X200 (C).

Table 1.

Summary of immunohistochemical staining in 10 cases of sporadic chordomas & one case of TSC-associated chordoma

| Case # | pS6 | p4EBP1 | PTEN | pPRAS40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ++ | ++ | − | ++ |

| 2 | +++ | ++ | − | +++ |

| 3 | +++ | +++ | + | ++ |

| 4 | +++ | +++ | + | + |

| 5 | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| 6 | +++ | ++ | − | ++ |

| 7 | +++ | ++ | − | ++ |

| 8 | +++ | +++ | + | nd |

| 9 | +++ | +++ | − | nd |

| 10 | ++ | +++ | − | nd |

| a TSC-associated chordoma | +++ | +++ | ++ | nd |

Note: Two independent observers blindly scored staining semiquantitatively: −, negative; +, weak; ++, medium; +++, strong; nd, not determined.

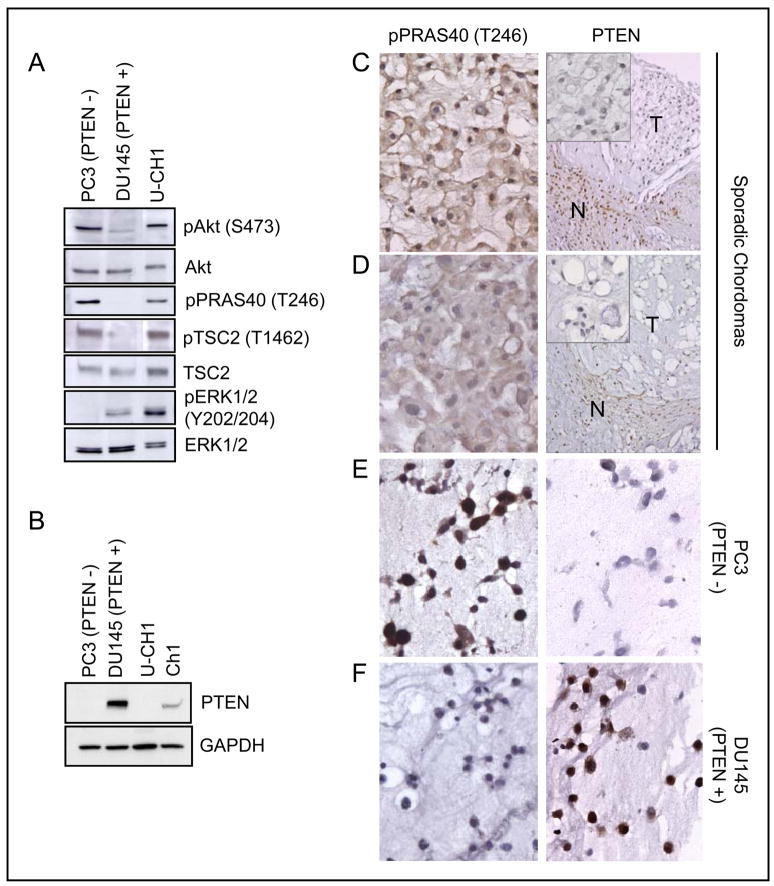

Constitutively activated Akt signaling and PTEN loss in U-CH1 cells

To determine the mechanism of constitutively elevated mTORC1 signaling in U-CH1 cells, we examined Akt/TSC and MAPK signaling pathways, which are well-known upstream regulators of mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 1A). Activated Akt, ERK, and RSK1 kinases phosphorylate and inactivate the tumor suppressor TSC2, thus relieving its inhibitory role on mTORC1. Akt also phosphorylates and inactivates a novel mTOR-binding partner PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa), a negative regulator of mTORC1 (Fig.1) (23). Similar to PC3 cells, serum-starved U-CH1 cells exhibited high levels of pAkt, pTSC2, and pPRAS40, compared to serum-starved DU145 cells (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that Akt signaling in U-CH1 cells is also constitutively activated in a growth factor-independent manner. Interestingly, ERK phosphorylation was also high in serum-starved U-CH1 cells.

Figure 3.

Constitutively activated Akt signaling and PTEN deficiency in chordoma-derived cell lines and sporadic sacral chordoma tumors. A, constitutive phosphorylation of Akt, TSC2, PRAS40, and ERK in U-CH1 cells. Cells were serum-starved for 20 hr before lysates were prepared for western analysis. B, PTEN expression was not observed in U-CH1 cells and significantly reduced in Ch1 cells. PTEN-negative PC3 and PTEN-positive DU145 cells were used as negative and positive controls for PTEN expression. C and D, representative images of two sporadic chordomas showing negative staining with anti-PTEN and positive staining with anti-pPRAS40 (T246) antibodies. N, non-neoplastic normal cells; T, tumor. Magnification: X 400 (left column and insets in right column); X 200 (right column). E and F, PTEN-negative PC3 cells (E) and PTEN-positive DU145 (F) cells showing pPRAS40 and PTEN staining. Magnification: X 400.

We next examined expression of the tumor suppressor PTEN, which is a negative regulator of Akt signaling. Strikingly, PTEN expression was not observed in U-CH1 cells, similar to PTEN-negative PC3 cells, and was significantly reduced in Ch1 cells (Fig. 3B). However, PTEN was robustly expressed in PTEN-positive DU145 cells. These results suggest that constitutively high Akt activity, due to PTEN loss, may be responsible for hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling through inactivation of TSC2 and PRAS40 in U-CH1 cells.

Loss of PTEN expression in sporadic chordomas

We next examined PTEN expression by immunohistochemical staining in sporadic sacral chordomas and a TSC-associated chordoma. Surprisingly, 4 out of 10 sporadic cases stained rather weakly and 6 out of 10 sporadic cases were negative for PTEN staining, while a TSC-associated chordoma stained positive (Table 1). Results from two representative sporadic chordomas are shown (Fig. 3C, D). In supportive of these results, 5 out of 7 sporadic chordomas stained positive for pPRAS40 (T246) and 2 out of 7 cases displayed weak signal (Fig. 3C, D and Table 1). As expected, PTEN-positive DU145 control cells stained strongly for PTEN and revealed negative staining for pPRAS40. PTEN-negative PC3 control cells exhibited no staining for PTEN and showed a strong staining for pPRAS40 (Fig. 3E, F). These results suggest that partial or complete deficiency of PTEN could be responsible for hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling in at least a subset of chordomas.

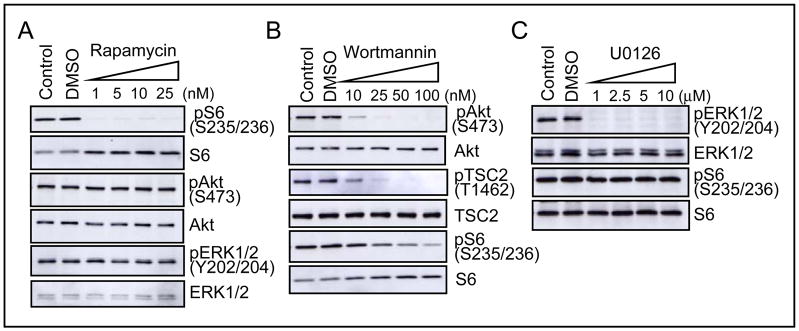

Rapamycin-sensitive mTORC1 signaling and proliferation of U-CH1 cells

In order to characterize constitutively high, growth factor-independent mTORC1 signaling in U-CH1 cells, the effect of the mTOR-specific inhibitor rapamycin was examined. Upon treatment with rapamycin, S6 phosphorylation in serum-starved U-CH1 cells was completely eliminated at concentrations as low as 1 nM, but phosphorylation of Akt and ERK was not downregulated (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that constitutive S6 phosphorylation in U-CH1 cells requires mTOR activity.

Figure 4.

Rapamycin and wortmannin suppress mTORC1 signaling in serum-starved U-CH1 cells. U-CH1 cells were serum-starved for 20 hr and treated with DMSO (0.1%) or varying concentration of rapamycin, wortmannin, or U0126 for 30 min. A, rapamycin completely inhibited S6 phosphorylation, but not either Akt or ERK phosphorylation. B, wortmannin effectively suppressed phosphorylation of Akt, TSC2 and S6. C, U0126 abolished ERK phosphorylation, but not S6 phosphorylation.

We next examined the effect of the upstream PI3K and MEK inhibitors wortmannin and U0126, respectively. Wortmannin significantly diminished phosphorylation of Akt and TSC2 at a low concentration of 10–25 nM, and gradually inhibited S6 phosphorylation in serum-deprived U-CH1 cells (Fig. 4B). However, the MEK inhibitor U0126 was unable to suppress S6 phosphorylation, although it completely abolished ERK phosphorylation as expected (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that hyperactive PI3K/Akt activity, and not ERK/MAPK activity, is responsible for constitutive mTORC1 signaling through TSC2 inactivation in U-CH1 cells.

In order to assess the effect of rapamycin on proliferation of U-CH1 cells, we kept track of cell counts with increasing dosage of rapamycin over the course of 9 days. Compared to the control group treated with vehicle DMSO, rapamycin treatment resulted in a decrease in cell number even at 1 nM concentration, which was observed as early as Day 3 with no significant increase in cell numbers through Day 9 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, rapamycin treatment as low as 5 nM resulted in a significant decrease of BrdU incorporation into U-CH1 cells, compared to DMSO-treated control group (Fig. 5B). Therefore, these data demonstrate that inhibition of mTORC1 signaling may be effective in repressing proliferation of U-CH1 cells.

Figure 5.

Rapamycin suppresses proliferation of U-CH1 cells. A, cell growth was suppressed by rapamycin. Cells were cultured in growth media in the presence of DMSO (0.1%) or varying concentrations of rapamycin up to 9 days. At days 3, 6, and 9, cell numbers were determined. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, DMSO-treated control versus rapamycin-treated groups (p<0.01, n=3). B, diminished incorporation of BrdU in rapamycin-treated U-CH1 cells. Cells were cultured as in (A) for 7 days and treated with BrdU for the final 24 hr. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (percentage of DAPI-stained cells). *, DMSO-treated control versus rapamycin-treated groups (p<0.01, n=5).

Discussion

The pathogenic mechanism(s) of chordomas remain unclear and besides surgery there is no effective treatment for patients with chordomas. We demonstrate here for the first time that hyperactivity of Akt and mTORC1 signaling is common in sporadic sacral chordomas. We also observed lack of PTEN expression in approximately 60% (6 out of 10) of chordomas examined as well as the chordoma-derived U-CH1 cell line, suggesting that inactivation of PTEN may be responsible for Akt and mTORC1 activation and consequent development of at least a subset of sporadic chordomas. Genomic DNA analyses by comparative genomic hybridization revealed loss of chromosome 10 in 3 out of 16 sporadic chordomas where PTEN gene is located (19, 24). PTEN mutations are frequently found in glioblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, lung carcinoma, melanoma, endometrial carcinoma and prostate cancer (25, 26). Further genetic investigations are essential in order to confirm PTEN inactivation in a larger panel of sporadic chordomas. However, other possibilities including inactivating mutations in TSC genes or activating mutations in PI3K/Akt may also explain the mTOR dysregulation in sacral tumors. In addition, it will be interesting to extend these studies to sphenooccipital/clivus chordomas to understand whether Akt/mTOR signaling is also aberrantly regulated in these tumors.

Deregulation of cellular signaling pathways involving amplification/activating mutations in PI3K, Akt, S6K or loss/inactivating mutations in tumor suppressor including PTEN, NF1, TSC1, TSC2, VHL, and LKB1 all result in aberrant mTOR activation commonly seen in several hamartoma syndromes and other human cancers (16, 18, 27). Due to their ability to block cell proliferation and angiogenesis, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and its analogues, such as RAD001 (Novartis) and CCI-779 (Wyeth), are currently being tested in clinical trials on a wide range of tumors, including those associated with TSC as well as LAM (28). Many reports demonstrate the effectiveness of rapamycin in treatment of several cancers, such as renal cell carcinoma (29), TSC-associated AML (30, 31), TSC-associate astrocytomas (32), Kaposi’s sarcoma (33), acute myeloid leukemia (34), and mantle-cell lymphoma (35). In addition, PTEN-negative cells have enhanced sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors (36–38). Taken together, our findings imply that mTOR inhibition may provide clinical benefits to chordoma patients. In addition, combined treatment with PI3K inhibitor and mTORC1 inhibitor may be more potent, since hyperactivation of PI3K/Akt activity is known to critically contribute to dysregulation in cell proliferation.

In summary, we found that PTEN deficiency and hyperactivation of Akt/mTORC1 signaling are strongly associated with sporadic sacral chordomas. mTORC1 inhibition is effective in suppressing proliferation of chordoma-derived cell line. Therefore, this study adds sporadic chordoma to the growing list of mTORC1-hyperactivated tumors, and provides a rationale for initiating clinical trials of Akt/mTOR inhibition in patients with sporadic chordomas. However, given the low incidence of chordomas, it would be necessary to build national/international collaborations and/or partner with other sarcoma initiatives in order to have sufficient number of patients for clinical trial.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter Moller (University Hospitals of Ulm, Germany) for providing U-CH1 cell line and the Chordoma Foundation for their support.

Grant support: National Institute of Health Grant NS24279.

References

- 1.Casali PG, Stacchiotti S, Sangalli C, Olmi P, Gronchi A. Chordoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:367–70. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3281214448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stepanek J, Cataldo SA, Ebersold MJ, et al. Familial chordoma with probable autosomal dominant inheritance. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75:335–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980123)75:3<335::aid-ajmg23>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhadra AK, Casey AT. Familial chordoma. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:634–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B5.17299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miozzo M, Dalpra L, Riva P, et al. A tumor suppressor locus in familial and sporadic chordoma maps to 1p36. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley MJ, Korczak JF, Sheridan E, Yang X, Goldstein AM, Parry DM. Familial chordoma, a tumor of notochordal remnants, is linked to chromosome 7q33. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:454–60. doi: 10.1086/321982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang XR, Beerman M, Bergen AW, et al. Corroboration of a familial chordoma locus on chromosome 7q and evidence of genetic heterogeneity using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) Int J Cancer. 2005;116:487–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borgel J, Olschewski H, Reuter T, Miterski B, Epplen JT. Does the tuberous sclerosis complex include clivus chordoma? A case report Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:138. doi: 10.1007/s004310000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dutton RV, Singleton EB. Tuberous sclerosis: a case report with aortic aneurysm and unusual rib changes. Pediatr Radiol. 1975;3:184–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01006909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder BA, Wells RG, Starshak RJ, Sty JR. Clivus chordoma in a child with tuberous sclerosis: CT and MR demonstration. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987;11:195–6. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198701000-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lountzis NI, Hogarty MD, Kim HJ, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Cutaneous metastatic chordoma with concomitant tuberous sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:S6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storm PB, Magge SN, Kazahaya K, Sutton LN. Cervical chordoma in a patient with tuberous sclerosis presenting with shoulder pain. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43:167–9. doi: 10.1159/000098396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee-Jones L, Aligianis I, Davies PA, et al. Sacrococcygeal chordomas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex show somatic loss of TSC1 or TSC2. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;41:80–5. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez M, Sampson J, Holtes-Whittemore V. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Vol. 10. Oxford University Press; 1999. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato T, Seyama K, Fujii H, et al. Mutation analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in Japanese patients with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Hum Genet. 2002;47:20–8. doi: 10.1007/s10038-002-8651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carsillo T, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6085–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. 2008;412:179–90. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nature Genetics. 2005;37:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheil S, Bruderlein S, Liehr T, et al. Genome-wide analysis of sixteen chordomas by comparative genomic hybridization and cytogenetics of the first human chordoma cell line, U-CH1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;32:203–11. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han S, Witt RM, Santos TM, Polizzano C, Sabatini BL, Ramesh V. Pam (Protein associated with Myc) functions as an E3 Ubiquitin ligase and regulates TSC/mTOR signaling. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1084–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han S, Santos TM, Puga A, et al. Phosphorylation of tuberin as a novel mechanism for somatic inactivation of the tuberous sclerosis complex proteins in brain lesions. Cancer Research. 2004;64:812–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Molecular Cell. 2002;10:151–62. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, et al. PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase. Mol Cell. 2007;25:903–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallor KH, Staaf J, Jonsson G, et al. Frequent deletion of the CDKN2A locus in chordoma: analysis of chromosomal imbalances using array comparative genomic hybridization. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:434–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–47. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risinger JI, Hayes AK, Berchuck A, Barrett JC. PTEN/MMAC1 mutations in endometrial cancers. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4736–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. The TOR pathway: a target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:335–48. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E. Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:671–88. doi: 10.1038/nrd2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pantuck AJ, Thomas G, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma: current status and future applications. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:607–13. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wienecke R, Fackler I, Linsenmaier U, Mayer K, Licht T, Kretzler M. Antitumoral activity of rapamycin in renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:e27–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:140–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franz DN, Leonard J, Tudor C, et al. Rapamycin causes regression of astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:490–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.20784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stallone G, Schena A, Infante B, et al. Sirolimus for Kaposi’s sarcoma in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1317–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Recher C, Beyne-Rauzy O, Demur C, et al. Antileukemic activity of rapamycin in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;105:2527–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5347–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neshat MS, Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, et al. Enhanced sensitivity of PTEN-deficient tumors to inhibition of FRAP/mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10314–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171076798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi Y, Gera J, Hu L, et al. Enhanced sensitivity of multiple myeloma cells containing PTEN mutations to CCI-779. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5027–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu K, Toral-Barza L, Discafani C, et al. mTOR, a novel target in breast cancer: the effect of CCI-779, an mTOR inhibitor, in preclinical models of breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:249–58. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]