Abstract

Background

Recent investigations have suggested that adults with aphasia present with a working memory deficit that may contribute to their language-processing difficulties. Working memory capacity has been conceptualised as a single “resource” pool for attentional, linguistic, and other executive processing—alternatively, it has been suggested that there may be separate working memory abilities for different types of linguistic information. A challenge in this line of research is developing an appropriate measure of working memory ability in adults with aphasia. One candidate measure of working memory ability that may be appropriate for this population is the n-back task. By manipulating stimulus type, the n-back task may be appropriate for tapping linguistic-specific working memory abilities.

Aims

The purposes of this study were (a) to measure working memory ability in adults with aphasia for processing specific types of linguistic information, and (b) to examine whether a relationship exists between participants’ performance on working memory and auditory comprehension measures.

Method & Procedures

Nine adults with aphasia participated in the study. Participants completed three n-back tasks, each tapping different types of linguistic information. They included the PhonoBack (phonological level), SemBack (semantic level), and SynBack (syntactic level). For all tasks, two n-back levels were administered: a 1-back and 2-back. Each level contained 20 target items; accuracy was recorded by stimulus presentation software. The Subject-relative, Object-relative, Active, Passive Test of Syntactic Complexity (SOAP) was the syntactic sentence comprehension task administered to all participants.

Outcomes & Results

Participants’ performance declined as n-back task difficulty increased. Overall, participants performed better on the SemBack than PhonoBack and SynBack tasks, but the differences were not statistically significant. Finally, participants who performed poorly on the SynBack also had more difficulty comprehending syntactically complex sentence structures (i.e., passive & object-relative sentences).

Conclusions

Results indicate that working memory ability for different types of linguistic information can be measured in adults with aphasia. Further, our results add to the growing literature that favours separate working memory abilities for different types of linguistic information view.

Recent investigations have suggested that adults with aphasia present with a working memory deficit (e.g., Caspari, Parkinson, LaPointe, & Katz, 1998; Downey et al., 2004; Friedmann & Gvion, 2003; Yasuda & Nakamura, 2000), and this deficit may contribute to the language-processing difficulties found in these individuals (Caspari et al., 1998; Friedman & Gvion, 2003; Wright & Shisler, 2005). Working memory capacity has been conceptualised as a single “resource” pool for attentional, linguistic, and other executive processing (e.g., Just & Carpenter, 1992). It has also been suggested that there may be separate working memory abilities for different types of linguistic information (e.g., Caplan & Waters, 1999; Friedmann & Gvion, 2003, 2006). Moreover, individuals with aphasia may exhibit differential difficulty in processing distinct types of linguistic information, such as phonological, semantic, and syntactic (Angrilli, Elbert, Cusumano, Stegagno, & Rockstroh, 2003; Martin, Wu, Freedman, Jackson, & Lesch, 2003; Vallar, Corno, & Basso, 1992; Waters & Caplan, 1996, 1999), which may contribute to their overall difficulties with language. Friedmann and Gvion (2003) suggested that the effect of a verbal working memory deficit on sentence comprehension is dependent on the type of processing (i.e., semantic, syntactic, phonological) required in the sentence.

A challenge in investigating working memory in aphasia is developing an appropriate measure. This has met with mixed success. Historically, adaptations of Daneman and Carpenter’s Reading Span test (1980) have been administered to individuals with aphasia in an effort to measure working memory capacity. Such tasks require participants to process multiple types of information (i.e., phonological, semantic, syntactic) simultaneously, while also remembering sentence-final words for later recall or recognition. Not surprisingly, many individuals perform poorly on such tasks (Caspari et al., 1998; Tompkins, Bloise, Timko, & Baumgaertner, 1994; Wright, Newhoff, Downey, & Austermann, 2003). Yet, due to the conflation of distinct linguistic information types involved in such a task, it is impossible to determine where breakdowns occur.

One candidate measure of working memory ability that may be appropriate for this population is the n-back task (the task is described in detail in the Method section). Downey et al. (2004) suggested that an n-back task might be useful in differentiating individuals with aphasia based on working memory ability. To perform the n-back task different cognitive processes are required, including storing n information in working memory and continuously updating contents of working memory by dropping the old, unnecessary information and adding the newly presented information (Jonides, Lauber, Awh, Satoshi, & Koeppe, 1997). This task is commonly used to measure working memory ability in functional neuroimaging studies for several reasons. The task does not require an overt verbal response; participants can respond with a button press. Task difficulty can be increased parametrically by increasing the n back, thus increasing memory load and taxing the participant’s working memory system. Also, by including several levels of the n-back (i.e., 0-back, 1-back, 2-back), a baseline task is not needed; rather, comparisons can be made between the different task levels. Finally, by manipulating stimulus type, the n-back task may be appropriate for tapping linguistic-specific working memory abilities. For these reasons, the n-back task may be an appropriate measure of working memory ability in adults with aphasia and differentiating individuals based on linguistic-specific working memory ability.

The present study is a follow-up to the study by Downey and colleagues (2004). In the initial study, we determined if the n-back task, using semantically related stimuli, was appropriate to use with adults with aphasia and if a relationship existed between performance on the working memory measure and performance on a syntactic, auditory comprehension measure. Participants’ performance declined as n-back task difficulty increased, but no relationship was found between performance on the n-back and comprehension measures. However, the two tasks tapped different types of linguistic information (i.e., semantic and syntactic). Friedmann and Gvion (2003) hypothesised that to measure the effect of a working memory limitation on sentence comprehension, the type of reactivation required, the memory load, and the working memory limitation all need to be the same (i.e., phonological, syntactic, etc.), and they demonstrated this with adults with conduction aphasia. That is, the participants with conduction aphasia presented with a phonological working memory deficit and struggled when comprehending sentences that required phonological reactivation. Continuing to investigate this tripartite relationship in adults with aphasia by tapping different types of linguistic information is a logical next step to further unravel the relationship between sentence comprehension and working memory. The purposes of the current study, then, were (a) to measure working memory ability in adults with aphasia for processing specific types of linguistic information, and (b) to examine whether a relationship exists between participants’ performance on working memory and auditory comprehension measures.

METHOD

Participants

Nine adults with aphasia participated in the study. Participants included one female and nine males, ages 44 to 80 (Mean = 57.3; SD = 13.1). Years of education completed ranged from 8 to 20+ (Mean = 14.9, SD = 2.2). All participants presented with unilateral left hemisphere damage subsequent to cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Clinical criteria for participation included (a) no more than one stroke located in the left hemisphere, (b) at least 6 months post onset of the stroke, (c) pre-morbid right-handedness, and (d) no history of dementia or other neurological illness. In addition to the previously mentioned inclusion criteria, all participants also met the following criteria: (a) aided or unaided hearing acuity within normal limits; (b) normal or corrected visual acuity; and (c) sufficient dexterity control to make responses using a computer keyboard or button-box. All participants presented with aphasia as confirmed by clinical diagnosis and performance on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB; Kertesz, 1982). Aphasia quotients (AQ) were obtained for each participant who received the WAB. Participants included two adults classified with Broca’s aphasia, one with transcortical motor aphasia, one with conduction aphasia, and five with anomic aphasia. Although a more homogeneous group of participants in terms of behavioural presentation and severity of impairment would be preferred, participants were included in the study because they presented with damage in left anterior brain regions. Some also presented with damage extending to posterior regions. Table 1 presents group demographic and clinical description data.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and demographic data for participants

| Pt1 | Age | Educ2 | Sex | m/p CVA3 | WAB AQ4 | Aphasia type | Lesion information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | 16 | M | 51 | 58 | Broca’s | Left middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarct; upper left temporal & parietal lobes & left basal ganglia |

| 2 | 62 | 20+ | M | 31 | 81.7 | Conduction | Left temporal & frontal lobes; insular region |

| 3 | 44 | 17 | M | 17 | 68.1 | Transcortical-motor | Left basal ganglia & contiguous portions of the subinsular cortex; portions of left frontal & temporoparietal lobes |

| 4 | 76 | 12 | M | 152 | 48.1 | Broca’s | Left frontotemporal cerebral infarct |

| 5 | 47 | 16 | F | 104 | 91.1 | Anomic | No data available |

| 6 | 55 | 20 | M | 27 | 88.6 | Anomic | Left MCA |

| 7 | 45 | 17 | M | 56 | 72.3 | Anomic | Left MCA infarct with small intracerebral acute haematoma |

| 8 | 56 | 14 | M | 88 | 91.9 | Anomic | Left frontal cortical region; left basal ganglia |

| 9 | 80 | 12 | M | 62 | 84.7 | Anomic | Superior aspect of left perisylvian region extending to frontoparietal convexity |

| Mean | 57.3 | 14.9 | 43 | 76.1 |

patient

years of education completed

months post cerebrovascular accident

Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia Quotient.

Stimuli and tasks

N-back tasks

We developed three n-back tasks, each tapping different types of linguistic information. They included the PhonoBack, which tapped the phonological level, SemBack, tapping the semantic level, and SynBack, which tapped the syntactic level. For all tasks, two n-back levels were administered: a 1-back and 2-back, each containing 20 target items used for determining performance. All 1-back tasks comprised four blocks: one practice block of 10 items containing 2 targets; a second practice block of 12 items, with 3 targets; a third block of 32 items with 10 targets; and a fourth block of 33 items with 10 targets. All 2-back tasks similarly consisted of four blocks: 10 practice with 2 targets; 15 practice with 3 targets; 37 experimental with 10 targets; and 39 experimental with 10 targets. Thus, the percentages of tokens that were targets in the 1-back and 2-back were 31% and 27%, respectively. These percentages were selected to be consistent with n-back tasks in the literature while also falling within the ability level of the participants, to keep the tasks from being frustratingly long. The 1-back level required a response when the current token was the same as the one immediately preceding it (e.g., apple...peach...peach...). For the 2-back level, participants responded to any token that was identical to the item appearing two tokens prior (e.g., plum...apple...plum...).

The PhonoBack stimuli consisted of 25 CVC words, five ending in each of five frames: -at, -it, -in, -ill, and -ig. The SemBack stimuli consisted of five words from each of five different semantic categories: fruits, tools, furniture, animals, and clothing. Stimuli were controlled across categories for length and frequency of occurrence. The SynBack stimuli included five-word sentences with either active (“The doctor kissed the banker”) or passive (“The banker was kissed by the doctor”) sentence structures. Ten nouns and ten verbs were used; length, frequency of occurrence, and role (object/subject) were controlled. See Table 2 for stimuli used in the different n-back tasks.

TABLE 2.

Stimuli for PhonBack, SemBack, and SynBack tasks

| PhonoBack words | ||

| -at: bat, hat, rat, pat, mat1 | -in: pin, fin, bin, tin, kin | -ill: till, hill, pill, sill, gill |

| -ap: tap, cap, map, nap, sap | -ig: wig, rig, jig, pig, fig | |

| SemBack words | ||

| Animals: wolf, cat, snake, bird, rabbit | Tools: hammer, drill, pliers, hatchet, axe | |

| Furniture: chair, desk, dresser, couch, stool | Fruit: apple, orange, lemon, grape, lime2 | |

| Clothes: shirt, hat, jacket, blouse, pants | ||

| SynBack words | ||

| Verbs: pushed, called, punched, kicked, thanked, blamed, teased, kissed chased, hugged3 | ||

| Noun phrases: actor, golfer, doctor, banker, singer, teacher, lawyer, baker, jogger, mayor4 | ||

only words used in PhonoBack Identity tasks

only words used in SemBack Identity tasks

all verbs used in passive and active tenses

all noun phrases used as subjects and objects.

Each n-back task also consisted of two levels of processing—identity and depth. For identity versions, targets were identical to prime items presented n back. For all tasks, instructions were as follows: “Push the button when the word (sentence) you just heard is the same as the one [n] back.” Only depth versions of the PhonoBack and SemBack were administered. We anticipated that the depth version of the SynBack would be too challenging for this population, thus it was not administered. For the PhonoBack depth, participants responded when target items rhymed with the prime presented n back (e.g., cat - rat). For the SemBack depth, participants responded when target items matched the category of the prime presented n back (e.g., grapes - lime).

SOAP

Love and Oster (2002) developed the Subject-relative, Object-relative, Active, Passive Test of Syntactic Complexity (SOAP), and have demonstrated its validity and sensitivity for certain comprehension abilities in brain-damaged populations, as well as its ability to differentiate between subgroups of aphasia. Briefly, the SOAP requires participants to listen to a sentence produced by the experimenter and then point to the one picture, among two foils, that corresponds to the sentence. The test sentences conform to the following syntactic structures and are processed with differential success, depending on each aphasic individual’s comprehension deficits: subject-relative, object-relative, active, and passive. Because it contains 10 trial sentences from each of the four syntactic structures, the SOAP provides a sensitive and selective profile of an individual’s comprehension ability across a range of processing difficulty.

Experimental procedures

Assessment was completed prior to the experimental sessions. During the assessment phase, informed consent was obtained, the WAB was administered, and vision and hearing screenings were conducted. For the experimental study, each participant attended three sessions in a sound-insulated room. All participants received all 11 n-back conditions and the SOAP. The PhonoBack and SemBack identity versions were completed in the first session and the depth versions completed in the second session. Presentation order for the PhonoBack and SemBack was counterbalanced across participants and sessions. During the third session, the SynBack and SOAP were administered; presentation order was counterbalanced across participants. Participants were given ample time to respond during the SOAP; the n-back tasks were internally time-driven by a 4000-ms stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) regardless of stimulus length.

Practice items for the n-back tasks were administered to ensure that participants understood the instructions and were comfortable performing the tasks. Participants completed practice items on the computer identical to the experimental n-back tasks. To reduce any chance of task perseveration from one condition to the next, task training and practice preceded each condition. The participant was instructed to press a button on a button response box when the item heard matched the item n items back.

Stimuli were played through computer speakers or headphones at a volume comfortable for each participant. Accuracy and response times (RT) were recorded by stimulus presentation software with millisecond precision. Because participants were not specifically instructed to respond with any rapidity—only “quickly, as another item will be coming up soon”—RTs are not viewed here as an index of processing time and were not subjected to further analysis. Administration and scoring of the SOAP were performed according to the procedures developed and standardised by Love and Oster (2002).

RESULTS

N-back

To compare accuracy performance across levels of processing for the different n-back tasks, the SynBack data were not included because participants did not complete SynBack depth tasks. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) of information type (phonological, semantic) by level of processing (Identity, Depth) by n-back level (1-back, 2-back) was performed. The main effect for information type was significant, F(1, 8) = 5.40, p < .05, as were the main effects for level of processing, F(1, 8) = 12.89, p < .01, and n-back level, F(1, 8) = 75.57, p < .0001. Participants were more accurate on the SemBack task compared to the PhonoBack. Participants also were more accurate at the identity level than depth level and on the 1-back compared to the 2-back. The interactions were not significant. To compare participants’ accuracy performance across the different n-back tasks a repeated measures ANOVA of information type (phonological, semantic, syntactic) by n-back level was performed. Significant main effects were found for information type, F(2, 16) = 13.54, p < .001, and n-back level, F(1, 8) = 30.00, p < .001. Planned comparisons were performed. Although participants’ accuracy scores were better during SemBack tasks compared to PhonoBack and SynBack tasks, no significant findings emerged when controlling for family-wise error using an adjusted p of .0167 (.05/3).

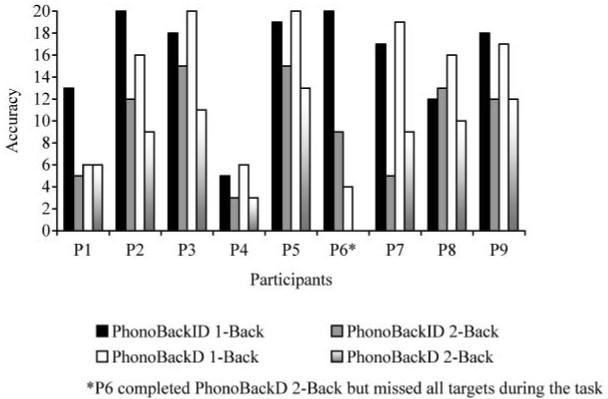

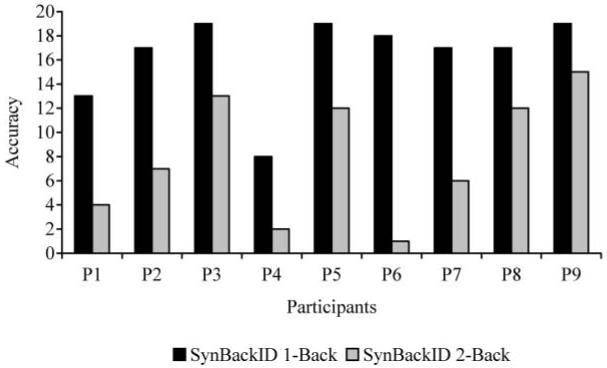

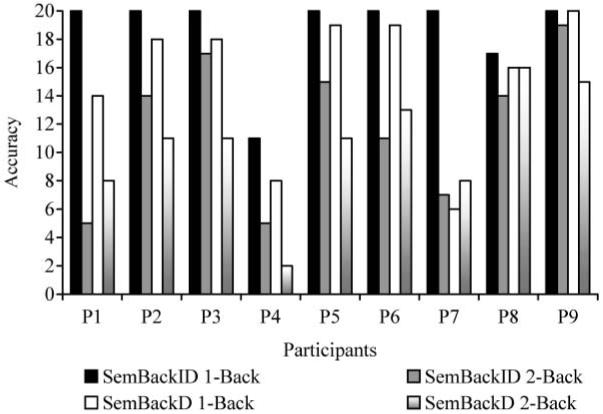

Finally, we inspected individual participant’s performances on the n-back tasks to determine if individual patterns were consistent with that of the group. Generally, all participants performed better on the 1-back tasks when compared to the corresponding 2-back tasks. When inspecting individual data within and among the different linguistic information versions some inconsistencies with group performance were found. For the PhonoBack, two participants performed appreciably better on the depth version compared to the identity version (i.e., P7 for 2-back, P8 for 1-back). When comparing across the tasks, one participant performed worse on the SemBack compared to the PhonoBack (i.e., P7 for depth tasks). In all other instances, individual patterns were comparable to that of the group. See Figures 1-3 for participants’ accuracy performance on the n-back tasks.

Figure 1.

Participants’ accuracy on the PhonoBack tasks.

Figure 3.

Participants’ accuracy on the SynBack tasks.

SOAP

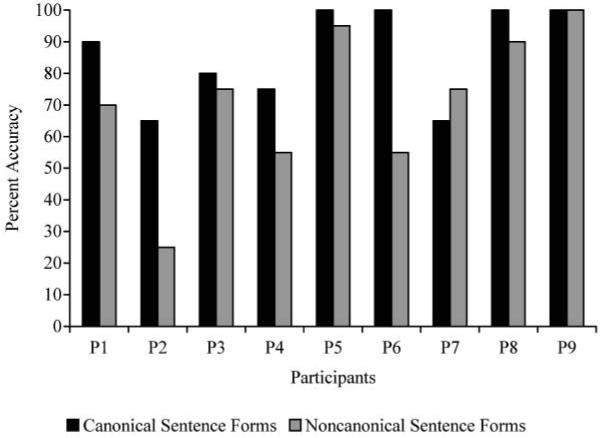

The SOAP was administered to assess participants’ auditory comprehension for four syntactic structures. Participants’ performance on the SOAP was grouped according to sentence canonicity and then subjected to statistical analysis. Using a paired sample t-test, participants comprehended the canonical sentences (i.e., active, subject-relative) significantly better than the non-canonical sentences (i.e., passive, object-relative), t(9) = 2.90, p < .05 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Participants’ percent accuracy on the Subject-relative, Object-relative, Active, Passive Test of Syntactic Complexity (SOAP; Love & Oster, 2002).

Relationship between working memory and language comprehension

Friedmann and Gvion (2003) hypothesised that a verbal working memory deficit affects sentence comprehension when the type of processing required is the same for both. The sentence comprehension task (i.e., SOAP) required processing syntactic information, thus it would be expected that participants who performed poorly on the SynBack would also perform poorly on the more complex sentence forms (i.e., non-canonical sentences) of the SOAP. Kendall’s Tau correlation, corrected for ties, was computed to determine the probability that participants’ performance on the SynBack 2-back identity task was similar to their performance on the SOAP non-canonical sentence forms. The non-parametric statistical analysis was performed because homogeneity of variance could not be assumed. Results indicated a significant relationship between participants’ performances on the SynBack 2-back and the SOAP non-canonical sentences, tau = .67, p < .05.

We also inspected individual patterns. Four participants (P1, P2, P4, P6) missed more than 50% of the targets on the SynBack 2-back task. These participants also evinced lower scores on the non-canonical sentences compared to the canonical sentences. Other participants (P3, P5, P8, P9), who differed by less than 10% in accuracy between canonical and non-canonical sentences on the SOAP and performed well on the SOAP, yielded higher hit rates on the SynBack task. One participant did not fit either grouping; P7 performed poorly on the SynBack but demonstrated a stable performance across all sentence forms on the SOAP (see Figures 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

The primary goals of this study were to measure working memory ability for processing specific types of linguistic information and to identify whether a relationship existed between working memory ability and auditory comprehension of different syntactic structures in adults with aphasia. Participants’ performance declined as n-back task difficulty increased. Further, participants performed more poorly on the depth versions of the PhonoBack and SemBack compared to the identity versions. Although participants overall performed better on the SemBack than PhonoBack and SynBack tasks, the differences were not statistically significant. Finally, participants’ performance on the SynBack 2-back task significantly correlated with their performance on the SOAP non-canonical sentence forms.

Working memory performance

The participants were able to perform the working memory tasks, supporting our previous work (Downey et al., 2004) that the tasks are appropriate for measuring working memory ability in adults with aphasia. As expected, the participants with aphasia performed similarly to participants without neurological impairment (Jonides et al., 1997; Yoo, Paralkar, & Panych, 2004), with traumatic brain injury (Levin et al., 2004), and with schizophrenia (Callicott et al., 2000) in previous studies using an n-back task; that is, participants’ accuracy declined as the n-back increased.

Previous n-back studies have manipulated stimulus type to tap different types of working memory, such as spatial, visual, auditory, and verbal (e.g., Hinkin et al., 2002; Kubat-Silman, Dagenbach, & Absher, 2002; McEvoy, Smith, & Gevins, 1998). No known study to date has manipulated n-back stimuli to tap different types of linguistic information as we did. Many of the participants’ performances differed across the n-back tasks. For example, some participants (P1, P2, P4, P6) had better hit rates on the SemBack tasks compared to the PhonoBack and SynBack tasks, suggesting that these individuals with aphasia demonstrate differential difficulty in processing distinct types of linguistic information. That is, they had more difficulty processing phonological and syntactic information versus lexico-semantic. Belleville, Caza, and Peretz (2003) found that individuals with anterior lesions present with structural (i.e., phonological, syntactic) deficits and a relative strength in processing lexico-semantic information. Although our participants who demonstrated this differential performance did present with anterior damage at the cortical and/or subcortical level, other participants who performed similarly across the three n-back tasks also presented with anterior damage. Further, many of the participants presented with damage in both anterior and posterior brain regions. At this point, our results do not support any hypotheses regarding the relationship between lesion location and processing of different types of linguistic information.

Sentence comprehension and WM

Our results add to previous findings indicating that individuals with aphasia may exhibit differential difficulty in processing distinct types of linguistic information, such as phonological, semantic, and syntactic (Angrilli et al., 2003; Martin et al., 2003; Vallar et al., 1992; Waters & Caplan, 1996, 1999), which may contribute to their overall difficulties with language. Friedmann and Gvion (2003, 2006) demonstrated that individuals with conduction aphasia presenting with a phonological working memory deficit struggle when comprehending sentences that require phonological reactivation, yet have minimal difficulty comprehending syntactically complex sentences. Thus, demonstrating that a linguistic-specific working memory deficit does affect sentence comprehension when that specific type of processing (i.e., semantic, syntactic, phonological) is required. We found similar results with a different type of linguistic process—syntactic. The participants who demonstrated a syntactic working memory deficit had the most difficulty comprehending syntactically complex sentences.

Although all participants demonstrated a decline in accuracy as the n-back task increased in difficulty, four participants’ working memory for syntactic information was severely stressed as the SynBack level increased. These participants’ performance on the sentence comprehension task also deteriorated as task difficulty increased; that is, comprehending non-canonical sentence forms compared to canonical sentence forms. Further, those participants who performed better on the SynBack overall and had a smaller decline in performance from the 1-back to 2-back on the SynBack did not have any trouble comprehending the more syntactically complex sentences. The one exception, P7, demonstrated poor performance on all 2-back tasks as well as both SemBack Depth tasks (i.e., 1-back and 2-back) suggesting that he may have a more “overarching” working memory deficit.

Conclusions and future directions

Results of this preliminary study investigating working memory ability and its relationship with sentence comprehension ability in aphasia are promising. First, we demonstrated that working memory ability for different types of linguistic information can be measured in adults with aphasia. Further, it had been hypothesised that a syntactic working memory deficit may contribute to the syntactic comprehension deficit found in some individuals with aphasia. However, prior to this study this hypothesis had not been tested and no measure of working memory ability for syntactic information had been proposed. Although these results are preliminary they add to the growing literature that favours the separate working memory abilities for different types of linguistic information view. To further evaluate the relationship between working memory and language comprehension, the next step in this line of research is to include sentence comprehension tasks that require different types of processing as well as working memory tasks for different types of linguistic information, and to include adults with aphasia with distinct lesion sites (i.e., anterior vs posterior).

Figure 2.

Participants’ accuracy on the SemBack tasks.

REFERENCES

- Angrilli A, Elbert T, Cusumano S, Stegagno L, Rockstroh B. Temporal dynamics of linguistic processes are reorganised in aphasics’ cortex: An EEG mapping study. Neuroimage. 2003;20:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleville S, Caza N, Peretz I. A neuropsychological argument for a processing view of memory. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;48:686–703. [Google Scholar]

- Callicott J, Bertolino A, Mattay V, Langheim FJP, Duyn J, Coppola R, et al. Physiological dysfunction of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia revisited. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10:1078–1092. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.11.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Waters G. Verbal working memory capacity and language comprehension. Behavioral Brain Sciences. 1999;22:114–126. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99001788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspari I, Parkinson S, LaPointe L, Katz R. Working memory and aphasia. Brain and Cognition. 1998;37:205–223. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1997.0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Carpenter PA. Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1980;19:450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Downey RA, Wright HH, Schwartz RG, Newhoff M, Love T, Shapiro LP. Toward a measure of working memory in aphasia; Poster presented at Clinical Aphasiology Conference; Park City, UT, USA. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann N, Gvion A. Sentence comprehension and working memory limitation in aphasia: A dissociation between semantic-syntactic and phonological reactivation. Brain and Language. 2003;86:23–39. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann N, Gvion A. Is there a relationship between working memory limitation and sentence comprehension? A study of conduction and agrammatic aphasia; Technical session presented at Clinical Aphasiology Conference; Ghent, Belgium. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, Castellon SA, Lam MN, Stefaniak M, et al. Verbal and spatial working memory performance among HIV-infected adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:532–538. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702814278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Lauber EJ, Awh E, Satoshi M, Koeppe RA. Verbal working memory load affects regional brain activation as measured by PET. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9(4):462–475. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA. A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working. Psychological Review. 1992;99:122–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. Western Aphasia Battery. Grune & Stratton; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kubat-Silman AK, Dagenbach D, Absher JR. Patterns of impaired verbal, spatial, and object working memory after thalamic lesions. Brain and Cognition. 2002;50:178–193. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(02)00502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, Hanten G, Zhang L, Swank PR, Ewing CL, Dennis M, et al. Changes in working memory after traumatic brain injury in children. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:240–247. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love T, Oster E. On the categorization of Aphasic typologies: The S.O.A.P, a test of syntactic complexity. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2002;31:503–529. doi: 10.1023/a:1021208903394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RC, Wu D, Freedman M, Jackson EF, Lesch M. An event-related fMRI investigation of phonological versus semantic short-term memory. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2003;16(45):341–360. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy L, Smith M, Gevins A. Dynamic cortical networks of verbal and spatial working memory: Effects of memory load and task practice. Cerebral Cortex. 1998;8:563–574. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.7.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CA, Bloise CGR, Timko ML, Baumagaertner A. Working memory and inference revision in brain-damaged and normally aging adults. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:896–912. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3704.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallar G, Corno M, Basso A. Auditory and visual verbal short-term memory in aphasia. Cortex. 1992;28:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters G, Caplan D. The measurement of verbal working memory capacity and its relation to reading comprehension. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1996;49A(1):51–79. doi: 10.1080/713755607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters G, Caplan D. Verbal working memory capacity and on-line sentence processing efficiency in the elderly. In: Kepmer S, Kliegle R, editors. Constraints on language: Aging, grammar and memory. Kluwer; Boston, MA: 1999. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wright HH, Newhoff M, Downey R, Austermann S. Additional data on working memory in aphasia. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9(2):302. [Google Scholar]

- Wright HH, Shisler R. Working memory in aphasia: Theory, measures, and clinical implications. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2005;14:107–118. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2005/012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda K, Nakamura T. Comprehension and storage of four serially presented radio news stories by mild aphasic subjects. Brain and Language. 2000;75:399–415. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S-S, Paralkar G, Panych LP. Neural substrates associated with the concurrent performance of dual working memory tasks. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;114:613–631. doi: 10.1080/00207450490430561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]