Abstract

We propose that people judge immoral acts as more offensive and moral acts as more virtuous when the acts are psychologically distant than near. This is because people construe more distant situations in terms of moral principles, rather than attenuating situation-specific considerations. Results of four studies support these predictions. Study 1 shows that more temporally distant transgressions (e.g., eating one's dead dog) are construed in terms of moral principles rather than contextual information. Studies 2 and 3 further show that morally offensive actions are judged more severely when imagined from a more distant temporal (Study 2) or social (Study 3) perspective. Finally, Study 4 shows that moral acts (e.g., adopting a disabled child) are judged more positively from temporal distance. The findings suggest that people more readily apply their moral principles to distant rather than proximal behaviors.

Keywords: Psychological distance, Moral judgment, Construal level theory

Introduction

Most people would agree that it is wrong to make love with a sibling, eat the family's pet, or clean the house with one's national flag. Recent research on moral judgment has shown that even when information about the context indicates that such actions are harmless (e.g., siblings use contraceptives), people still feel that they are wrong (Haidt, 2001). It appears that people hold general moral rules that, when violated, evoke a harsh moral judgment regardless of information about the context in which the violation occurs (see Haidt, 2001; Sunstein, 2005). According to Haidt (2001), the application of moral rules is immediate and spontaneous, and it is only if one subsequently engages in reflective reasoning that mitigating contextual factors are taken into account.

But is the unconditional reliance on general moral rules universal, or do extenuating circumstances sometimes attenuate people's judgments of morality? We propose that the reliance on general moral rules and the relative neglect of context-specific considerations depends on psychological distance. We specifically predict that general moral principles would be applied more readily to more psychologically distant situations making distant misdeeds seem more immoral and distant good deeds seem more moral.

Construal level theory

We base our predictions on construal level theory (CLT, Liberman, Trope, & Stephan, 2007; Trope & Liberman, 2003), which links psychological distance to level of construal. Psychologically distant events are those that a person does not experience directly because they are removed in time (future or past) or space, because they are hypothetical, or because they are another person's experiences (i.e., socially distant). Distant events cannot be experienced directly but may be mentally construed (e.g., imagined, remembered, or predicted). The basic tenet of CLT is that more distant events are represented on a higher-level, that is, more abstractly, with less concrete, contextual details. For example, “being a good person” is more abstract than “donating money” because it omits situational and less essential attributes of the concrete action (giving, money) and retains its abstract meaning.

The link between distance and level of construal has been demonstrated with temporal distance, social distance, spatial distance, and hypotheticality (for review, see Liberman et al., 2007). For example, Liberman, Sagristano, and Trope (2002) asked participants to list events that might happen to them on a good day or on a bad day in either the near or the distant future. They found that events in distant future good (bad) days were more uniformly good (bad), giving rise to an overall more extreme positive (negative) prototypical picture of a good (bad) day.

CLT further proposes that judgments reflect mental construal, such that psychological distancing increases the weight of abstract, global aspects of the situation and reduces the weight of secondary, contextual aspects. As a result, psychological distance should shift the evaluation of an event closer to the value that is reflected in its high-level construal than to the value that is reflected in its low-level construal. For example, Trope and Liberman (2000, Study 3) showed that temporal distance enhanced the tendency to evaluate an object (e.g., a radio set) in terms of its more primary, high-level aspects (quality of a radio's sound) rather than in terms of more secondary, low-level aspects (quality of clock installed in radio). The question we address in this paper is how the relationship between psychological distance and construal level apply to moral judgments.

Psychological distance and moral judgment

Research on morality suggests that people often base their judgments on moral rules and tend to ignore moderating contextual information (Haidt, 2001; Sunstein, 2005) For example, Sunstein (2005) argues that people use simple, intuitive rules when making moral judgments (e.g., it is wrong to lie). These moral heuristics represent generalizations from a range of problems for which they are well-suited (see Baron, 1994). However, these generalizations are often taken out of context and treated as universal principles that are applied to situations in which their justification does not hold (i.e., lying may save a human life).

In a similar vein, research on personal values has demonstrated that certain values, such as honor, love, justice, and life, called sacred values (e.g., Tetlock, Kristel, Elson, Green, & Lerner, 2000) or protected values (e.g., Baron & Spranca, 1997), are considered taboo. That is, individuals would protect these values from tradeoffs, no matter how small the sacrifice or how large the benefit is. This is because thinking in terms of protected values involves an overgeneralization of the no-tradeoff principle (e.g., never trade life with money), which does not allow for thinking about specific situations that violate the rule (e.g., crossing a busy street to pick up a check). However, as Baron and Leshner (2000) have argued, when people do think of concrete situations they may become less rigid in implementing their protected values. These researchers have shown that people compromise their protected values (e.g., genetically engineered wheat is bad) when the probability or amount of harm is small (e.g., one out of every million people who eat the new wheat will get a stomach ache from an allergic reaction to the new genes) relative to the probability or magnitude of benefit (e.g., the cost of growing wheat will decrease in the U.S., so that farmers will make more profit and sell the wheat at a lower price; see also Tetlock, 2005).

CLT suggests that, because of their general and decontextualized nature, moral principles (e.g., it is wrong to steal, donating to charity is noble) are high-level constructs. People are therefore more likely to rely on those principles rather than on contextual information when judging remote events compared to proximal events. If the relevant moral principle calls for a more clear-cut, extreme judgment whereas situational circumstances mitigate this conclusion, then judgment of more distal events would be more extreme.

We thus predict that when moral principles favor one judgment, whereas situational circumstances tilt judgment in the opposite direction, judgments of proximal events are less likely to reflect moral principles than judgments of distant events. For example, ignoring a person's cry for help would be typically judged as immoral. However, knowing that the potential helper was running late for an important meeting may moderate the harsh judgment when it is made from a proximal perspective rather than from a distant perspective.

The present research

The present research examines how temporal and social distances from an action affect construal and moral evaluation of the action. We focus on situations in which a moral rule leads to a positive (moral) or negative (immoral) evaluation of an action, whereas contextual information about extenuating circumstances undermines this judgment. We predict that more distant actions would be judged as more immoral if they transgress moral rules, and as more virtuous if they obey moral rules. Four studies test these predictions. Study 1 is preliminary in that it examines construal rather than judgment of actions. It tests the prediction that people construe temporally distant actions in terms of high-level, moral values more than in terms of low-level information. Building on the results of Study 1, Studies 2 through 4 assess moral judgments of proximal and distant actions. Specifically, Studies 2 and 3 examine the effect of temporal distance (Study 2) and social distance (Study 3) on the evaluation of moral transgressions. Finally, Study 4 examines the effect of temporal distance on the evaluation of morally virtuous actions. We predict that participants would judge moral or immoral actions more extremely, in a way that reflects moral principles more than situational concerns, when these actions are psychologically distant rather than near.

Study 1

Past research within the framework of construal level theory has shown that people choose more abstract identifications for temporally distant (vs. near) actions (Liberman & Trope, 1998; Liberman et al., 2002). The aim of Study 1 was to extend these findings to the domain of moral principles. We predicted that people are more likely to describe morally charged actions in terms of abstract moral values rather than in terms of more concrete incidental terms when the actions are temporally distant than temporally near. Participants imagined actions (e.g., cleaning one's house with the national flag) taking place either in the near future or in the distant future, and chose between two restatements of each action. One restatement referred to an abstract moral principle (high-level construal, e.g., desecrating a national symbol) and the other restatement referred to the means of carrying out the action (low-level construal, e.g., cutting a flag into rags).1 We predicted that participants would choose more moral principles, compared to concrete means, for describing temporally distant actions rather than temporally near actions.

Method

Participants

Thirty-nine psychology undergraduates (33 women) from Ben-Gurion University in Israel participated in the study for course credit. They were randomly assigned to the two temporal distance conditions.

Procedure

Participants were presented with five short vignettes describing a moral transgression: a sexual intercourse between siblings (adopted from Haidt, 2001), a family who ate their dead dog, a woman who cleaned the house with an old Israeli flag (both adopted from Haidt, Koller, & Dias, 1993), a married woman who had an affair, and a student who cheated on an exam. Each vignette was followed by two restatements, one corresponding to a general moral principle that the action represented (high-level restatement) and the other corresponding to specific means of performing the action (low-level restatement). The restatements for the siblings situation were “incest” (high-level) and “sexual intercourse between siblings” (low-level), the restatements for the affair situation were “breach of trust” (high-level) and “extramarital affair” (low-level), the restatements for the dog situation were “dishonoring a dead pet” (high-level) and “eating the meat of a dead dog” (low-level), the restatements for the flag situations were “desecrating a national symbol” (high-level) and “cutting a flag into rags” (low-level), and the restatements for the exam situation were “cheating” (high-level) and “peeking into another student's exam” (low-level).2 Participants were instructed to imagine the events happening tomorrow (near future condition) or next year (distant future condition) and to choose the restatement that best described the event. The order of the two types of restatement was randomized across participants.

All vignettes described a violation of a widely accepted moral rule (high-level information, e.g., incest taboo) as well as situational details that moderated the offensiveness of the action (low-level information, e.g., siblings used contraceptives, they did it just once). For example, the incest situation was described, in Hebrew, as follows:

A brother and sister are alone in the house and decide to make love just once. The sister is already taking birth control pills and the brother uses a condom. They both enjoy the act but decide not to do it again. They promise each other to keep it a secret.

Results and discussion

We conducted a temporal distance (near vs. distant future) - story (1–5) mixed ANOVA on the level of restatement chosen (low-level restatements were coded as 0 and high-level restatements were coded as 1). Time was a between-subjects factor and story was a within-subjects factor. The ANOVA yielded a main effect of story, F(4,36) = 15.41, p < .01, r = .61, indicating that some actions were identified in more high-level terms than others. More important, a main effect of temporal distance, F(1,36) = 5.87, p < .05, r = .14, indicated that distant future transgressions were identified in more high-level terms (M = .81, SD = .21) than near future transgression (M = .64, SD = .20). These findings support our initial prediction that the more distant future is more readily construed in terms of moral principles. People are more likely to think of an action as involving a moral choice when it is expected in the more distant future. Studies 2–4 examine the implications of this tendency for judging the wrongness or virtue of near and distant acts.

Study 2

Building on the findings of Study 1, Study 2 aims to demonstrate that distant moral transgressions would be judged more harshly than proximal transgressions. Participants judged the wrongness of moral transgressions performed under circumstances that made the transgressions harmless. As in Study 1, the transgressions were expected either on the next day (near future condition) or next year (distant future condition). We predicted that the same immoral actions would be judged more harshly when imagined from greater temporal distance.

Method

Participants

Participants were 58 Psychology undergraduate students (39 women) from Tel Aviv University who participated for course credit. There were no differences between male and female participants in the results reported below.3

Procedure

Participants read three of the short vignettes used in Study 1 (cleaning the house with a flag, eating one's dead dog, and a sexual intercourse between siblings). They were instructed to imagine that the events would happen tomorrow (near future condition) or next year (distant future condition). After reading each vignette, participants evaluated the wrongness of the actions on a scale ranging from −5 (very wrong) to +5 (completely okay).

Results and discussion

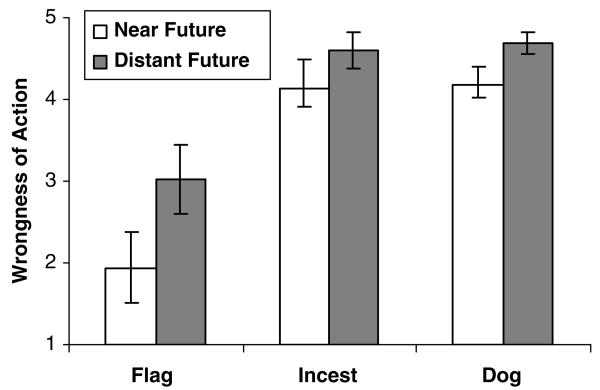

Since all the mean ratings were negative, for clarity of presentation, we converted them into positive scores by multiplying the mean rating by −1. Thus, higher numbers indicate higher wrongness ratings. A temporal distance (near vs. distant future) × story (1–3) mixed ANOVA on the wrongness ratings of the actions (time as a between-subjects factor, story as a within-subjects factor) yielded a main effect of story, F(2,56) = 26.79, p < .01, r = .57, indicating that some actions were judged as more wrong than others. More important, a main effect of temporal distance, F(1,56) = 6.53, p < .01, r = .38, indicated that distant future transgressions were judged as more wrong (M = 4.12; SD = .80) than near future transgression (M = 3.41; SD = 1.24; Fig. 1). The interaction was not significant, F < 1, indicating that the effect of temporal distance was consistent across all stories. Thus, as predicted, participants judged distant future moral transgressions more harshly than near future transgressions.

Fig. 1.

Wrongness of actions by temporal distance (Study 2). Higher numbers indicate higher wrongness ratings.

Study 3

Study 3 was designed to extend Study 2 by manipulating social distance (self vs. other) rather than temporal distance and by using additional situations. Participants were instructed to imagine moral transgressions either from one's own perspective (low social distance) or from another persons' perspective (high social distance). Past research has shown that a third person perspective induces a more abstract way of thinking than a first person perspective (e.g., Frank & Gilovich, 1989; Libby, Eibach, & Gilovoch, 2005; Nigro & Neisser, 1983). Applying this manipulation of social distance to our research question, we predicted that the same immoral actions would be judged more harshly when imagined from a third person rather than a first person perspective.

Method

Participants

Participants were 40 (29 women) workers in a security services organization in Israel who volunteered to participate in the study.

Procedure

Participants read six vignettes. In the low social distance condition participants were asked to focus on the feelings and thoughts they experienced while reading about the event. In the high social distance condition participants were asked to think about someone specific they knew, such as a colleague, a friend, a neighbor, or a family member. They were asked to focus on the feelings and thoughts that this person would experience while reading about the event.

Two vignettes (cleaning the house with a flag, eating one's dead dog) were the same as in the previous study. The other four vignettes were adopted from Haidt et al. (1993). They were about a girl who pushed another kid off a swing, two cousins who kissed each other on the mouth, a man who broke a promise to his dying mother, and a man who ate with his hands in public. After reading each vignette, participants evaluated how wrong the actions were either from their own perspective or from the perspective of another person, on a scale ranging from 1 (not okay) to 5 (completely okay).

Results and discussion

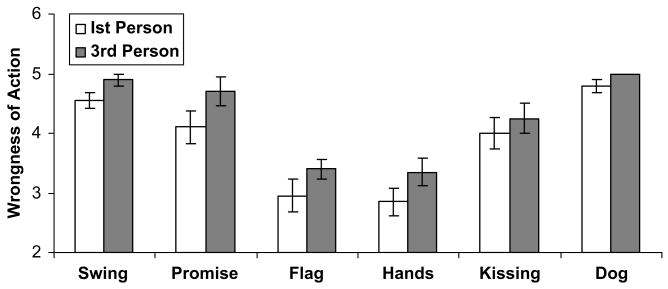

To be consistent with Study 2, we reverse scored participants' ratings so that higher ratings will indicate higher wrongness scores. A social distance (self vs. other) × story (1–6) mixed ANOVA on the evaluations of the actions (time as a between-subjects factor, story as a within-subjects factor) yielded a main effect of story, F(5,38) = 34.10, p < .01, r = .69, indicating that some actions were judged as more wrong than others. More important, a main effect of social distance, F(1,38) = 5.29, p < .05, r = .35, indicated that actions were judged as more wrong from a third person perspective (M = 4.27; SD = .47) than from a first person perspective (M = 3.88; SD = .60; Fig. 2). The interaction was not significant, F < 1, indicating that the effect of social distance on evaluations was consistent across all stories.

Fig. 2.

Wrongness of actions by social distance (Study 3). Higher numbers indicate higher wrongness ratings.

As predicted, participants judged moral transgressions more harshly from a more socially distant perspective. The results of both Studies 2 and 3 demonstrate that psychological distance influences the judgments of harmless immoral acts, presumably by augmenting the impact of moral considerations and discounting the impact of extenuating contextual considerations. These findings suggest that moral principles, because of their general and schematic nature, are more influential in judgments of more distant situations. When judging near situations, however, people allow contextual considerations moderate their moral stance. Would our analysis also apply to morally virtuous acts?

Study 4

Participants judged the virtuousness of near future and distant future moral actions performed under attenuating circumstances (e.g., adopting a disabled child; the government pays child's pension). Extending the logic of Studies 2 and 3, we predicted that participants would give more weight to moral values and less weight to attenuating circumstances when making judgments for the more distant future. In contrast to the previous studies, in the present study this should result in judging distant actions more positively than near actions.

Method

Participants

Participants were 47 (45 women), psychology undergraduate students from Ben-Gurion University, participating for course credit. They were randomly assigned to one of the temporal distance conditions (near vs. distant future).

Procedure

Participants read three vignettes that described virtuous acts related to widely accepted moral principles (high-level information) along with extenuating contextual details (low-level information). The vignettes were about a person who donated an inheritance to charity, a fashion company that donated clothes to the poor, and a couple that adopted a disabled child. For example, the adoption vignette read as follows:

A young couple discovers they are infertile. They decide to adopt a child and successfully pass the exams of the adoption agency. They are informed that the children that are available for adoption have various birth defects, which most likely caused their biological parents to abandon them. Adopters receive child's pension as well as a disability pension because of the children's condition. The couple does not have money for international adoption. They decide to proceed with the adoption.

Participants were asked to imagine the event occurring tomorrow (low temporal distance) or a year from now (high temporal distance) and to evaluate its virtuousness on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all virtuous) to 7 (very virtuous).

Results and discussion

A temporal distance (near vs. distant future) × story (1–3) mixed ANOVA on the virtuousness ratings (time as a between-subjects factor, action as a within-subjects factor) yielded a main effect of story, F(2,45) = 4.34, p < .05, r = .30, indicating that some actions were judged as more virtuous than others. More important, a main effect of temporal distance, F(1,45) = 7.65, p < .01, r = .38, indicated that participants judged the events as more virtuous in the distant future (M = 4.71; SD = .82) than in the near future (M = 3.97; SD = .99; Fig. 3). The interaction was not significant, F(2,45) = 1.20, p > .05, r = .16, indicating that the effect of temporal distance was consistent across actions.

Fig. 3.

Righteousness of actions by temporal distance (Study 4). Higher numbers indicate higher righteousness ratings.

As predicted, participants judged moral actions more positively from a greater temporal distance. We believe this was the case because when judging psychologically distant events, people give more weight to moral principles and less weight to attenuating contextual concerns. Together with Studies 1 through 3, these findings suggest that people employ high-level moral principals to the identification and judgment of more distant situations. From a near perspective, people allow attenuating contextual considerations to moderate their moral judgment.

General discussion

The present research suggests that the answer to the question “is it wrong to eat your dog,” posed by Haidt et al. (1993) is that it depends on when the action is conducted and by whom it is judged. Specifically, Study 1 demonstrates that individuals tend to construe more distant future situations in value-laden terms as opposed to concrete, value-neutral terms. Theoretically, the differences in construal influence individuals' moral judgments by leading them to judge more distant actions in terms of their moral principles rather than in terms of low-level contextual information. Indeed, Studies 2 and 3 demonstrates that morally offensive actions are judged more severely when these acts are thought to happen in the more distant future (Study 2) and when considered from a third person perspective rather than a first person perspective (Study 3). Study 4 demonstrates that moral actions are judged as more virtuous when they are more temporally distant.

Notably, we found that distance augmented moral evaluation of both moral transgressions and morally virtuous acts. Therefore, it was not the case that moral judgments were simply more positive for distal than proximal events. Moreover, the fact that similar results were obtained across two types of psychological distance (temporal, social) makes valence an unlikely alternative explanation, because typically more temporally distant events are seen as more positive (see, e.g., Gilovich, Kerr, & Medvec, 1993) whereas more socially distant events are seen as less positive (see, e.g., Miller & Ross, 1975). Rather, we maintain that our results were driven by a tendency to form schematic, high-level construals of the distant future and other people. Such construals highlight general moral rules and underweight contextual details that might moderate moral judgment.

The social distance effects we found are consistent with the notion that people are motivated to appear more complex than others, which might lead them to moderate their moral judgments (e.g., Hoorens, 1995). This possibility is consistent with CLT, because simplification (i.e., relying more on prototypes in thinking) is part of the definition of high-level construal. However, we cannot conclude from the present line of research whether complex moral judgments by self reflect a tendency to view oneself more positively. This possibility is not entirely consistent with our results on temporal distance, if we assume that people tend to have more positive distant future selves than near future selves. If this assumption is correct, then people should see themselves making more complex judgments in the more distant future, but this is not what our results show.

Of course, not only motivation, but also cognitive processes may contribute to a more complex perception of the self than of other people (e.g., Fiedler, Semin, Finkenauer, & Berkel, 1995; Prentice, 1990; Pronin, Gilovich, & Ross, 2004; Ross & Sicoly, 1979). We believe that by obtaining similar results for temporal distance (Studies 2 and 4) and for social distance (Study 3), we may more confidently conclude that psychological distance influences the judgment of moral and immoral acts by augmenting the relevance of general moral principles and discounting the relevance of mitigating contextual factors.

Similar to past research on moral judgment (Baron & Leshner, 2000; Haidt, 2001; Sunstein, 2005; Tetlock et al., 2000), the present findings suggest that people rely on general moral rules (e.g., incest taboo) when making moral judgments. Our findings extend this research by showing that the effect of general moral principles on judgment is moderated by psychological distance. From a distant perspective, transgressions appear more repugnant and virtuous acts more laudable. A more proximal perspective allows mitigating contextual considerations to muddle these clear-cut categorical judgments. We suggest that this might be the case because psychologically distant situations are more easily construed in moral terms. This may have important implications for decision making in domains that involve moral considerations, such as public policies, law, medicine, and consumer behavior. For example, adopting a remote perspective is likely to help a judge move beyond pragmatic and secondary concerns (e.g., plea bargain saves time and money) and rule according to general and cherished ethical and moral norms.

Note that the situational details we included in the vignettes were always mitigating in nature, discounting the wrongness of psychologically immediate immoral actions (Studies 2 and 3) or the virtuousness of psychologically immediate moral actions (Study 4). We would predict that accentuating situational information would augment rather than discount the wrongness or virtuousness of more proximate actions. For example, we predict that a person who donates for charity to an unattractive petitioner would look more virtuous from a more proximal perspective, because the augmenting contextual factor would lose its power in a more distal perspective. This prediction awaits future research.

Haidt (2001) has recently argued for two routes to moral judgment. According to his social intuitionist model, a rapid and effortless intuition-based judgment comes first, and is then followed by a more careful and reflective reasoning processes. In a study testing this model, Haidt, Bjorklund, and Murphy (2007, cited in Haidt & Bjorklund, 2008) found that participants strongly condemned harmless taboo violations with little reasoning or ability to justify their judgments (e.g., “I cannot explain why, but I think it is wrong”). From a construal level perspective, moral judgments of proximal actions are not necessarily more rational or less emotional than judgments of distant actions. In this respect, our analysis compliments rather than competes with existing theories of moral judgments. We do contend, however, that like any judgment, moral judgments are more likely to take into account the specifics of the situation when the judgments are about a near action than when a distant action is at stake (Liberman & Trope, 1998; Nussbaum, Trope, & Liberman, 2003; Trope & Liberman, 2000). We thus propose a distinction between general and principled judgments vs. contextual judgments, neither of which is inherently related to accuracy or effortfullness. In line with this assumption, we have recently demonstrated that judgments that were based on more abstract, high-level construals were no less effortful than judgments that were based on contextual, low-level construals (Fujita, Eyal, Trope, Liberman, & Chiaken, in press).

The present findings demonstrate that temporal distancing as well as social distancing, through taking another person's perspective, leads people to be more critical of moral offenses. These effects may be extended to other psychological distance dimensions. Liberman, Trope, and Stephan (2007; see also Trope & Liberman, 2003) have recently proposed that, similar to temporal and social perspective, other dimensions of psychological distance such as spatial distance and hypotheticality affect construal level. Based on this proposal, we suggest that individuals are more likely to make more extreme moral judgments in response to more physically distal actions as well as to more hypothetical actions. For example, an immoral action (e.g., plagiarism) is likely to be judged more harshly when conducted in a geographically distant location (a university in a foreign country) than in a nearby location (a university in my homeland).

In sum, our research examined how moral judgment is influenced by psychological distance. We showed that moral transgressions are judged more harshly and moral acts more virtuously when the acts are psychologically distant than near. It seems that moral values apply to distant situations more than to proximal situations. They are important “in principle” but less so in practice.

Footnotes

We conducted a pilot study to test whether people indeed perceive these two restatements as pertaining to different levels of abstraction. Thirty three undergraduates from Ben Gurion University were presented with five vignettes that were followed by two restatements, identical to those used in Study 1. Participants rated the extent to which each restatement was concrete vs. abstract on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (concrete) to 7 (abstract). Before providing their ratings, participants read the following definition of abstract vs. concrete restatements: “The more a restatement refers to a universal moral principle and is stated in a general way that applies to many situations, the more it is abstract” and “The more a restatement refers to the specific situation described in the vignette and not to other situations or a general moral rule, the more it is concrete.” As expected, all restatements pertaining to general moral principles were rated as more abstract than restatements pertaining to a specific violation, all t's > 4.00 and all p's < .01.

Our distinction between high-level and low-level restatements resembles that of action identification theory (Vallacher & Wegner, 1987), and may be viewed as an application of their distinction between why and how action identifications. Specifically, the high-level restatements in Study 1 (e.g., “desecrating a national symbol”) constitute a superordinate moral principle and pertain to why one shouldn't carry out the immoral action. The low-level restatements refer to the more specific details of how the action is performed (e.g., “cutting a flag into rags”).

Past research has often found gender differences in moral reasoning, but it is not clear whether they reflect different levels of abstraction (Kohlberg, 1984) or different emphases on interpersonal vs. general societal concerns (Gilligan, 1982). Because the majority of participants in our studies were women we cannot contribute to this debate. We cannot even conclude with certainty whether our data show gender differences because our null results are difficult to interpret. Let us note, however, that past research on the effects of psychological distance on construal and judgment did not reveal systematic gender differences (e.g., Liberman et al., 2002; Nussbaum et al., 2003).

This research was supported by a United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant #2001-057 to Nira Liberman and Yaacov Trope. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Tal Eyal, Department of Psychology, Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva 84105, Israel. E-mail: taleyal@bgu.ac.il.

References

- Baron J. Nonconsequentialist decisions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1994;17:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Baron J, Leshner S. How serious are expressions of protected values? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2000;6:183–194. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.6.3.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron J, Spranca M. Protected values. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1997;70:1–16. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1999.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K, Semin GR, Finkenauer C, Berkel I. Actor-observer bias in close relationships: The role of self-knowledge and self-related language. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:525–538. [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Gilovich T. Effect of memory perspective on retrospective causal attributions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;5:399–403. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Eyal T, Chaiken S, Trope Y, Liberman N. Influencing attitudes toward near and distant objects. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T, Kerr M, Medvec VH. The effect of temporal perspective on subjective confidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:552–560. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review. 2001;108:814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Bjorklund F. Social intuitionists answer six questions about morality. In: Sinnott-Armstrong W, editor. Moral psychology, Vol 2: The cognitive science of morality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008. pp. 181–217. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Koller S, Dias M. Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:613–628. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoorens V. Self-favoring biases, self-presentation and the self-other asymmetry in social comparison. Journal of Personality. 1995;63:793–817. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L. The psychology of moral development. San Francisco: Harper & Row; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Sagristano M, Trope Y. The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38:523–534. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y, Stephan E. Psychological distance. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Libby LK, Eibach RP, Gilovoch T. Here's looking at me: The effect of memory perspective on assessments of personal change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:50–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Ross M. Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G, Neisser U. Point of view in personal memories. Cognitive Psychology. 1983;15:467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum S, Trope Y, Liberman N. Creeping dispositionism: The temporal dynamics of behavior prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:485–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA. Familiarity and differences in self-and other-representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:369–383. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E, Gilovich TD, Ross L. Objectivity in the eye of the beholder: Divergent perceptions of bias in self versus others. Psychological Review. 2004;111:781–799. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.3.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M, Sicoly F. Egocentric biases in availability and attribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:322–336. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein CR. Moral heuristics. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28:531–573. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock PE. Gauging the heuristic value of heuristics. Commentary/Sunstein: Moral heuristics. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28:562–564. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock PE, Kristel OV, Elson SB, Green MC, Lerner JS. The psychology of the unthinkable: Taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:853–870. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.5.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trope Y, Liberman N. Temporal construal and time-dependent changes in preference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:876–889. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trope Y, Liberman N. Temporal construal. Psychological Review. 2003;110:403–421. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]