Abstract

Background & Aims

Conventional colonoscopy misses some neoplastic lesions. We compared the sensitivity of chromoendoscopy and colonoscopy with intensive inspection for detecting adenomatous polyps missed by conventional colonoscopy.

Methods

Fifty subjects with a history of colorectal cancer or adenomas underwent tandem colonoscopies at one of 5 centers of the Great-Lakes New England Clinical Epidemiology and Validation Center of the Early Detection Research Network. The first exam was a conventional colonoscopy with removal of all visualized polyps. The second exam was randomly assigned as either pan-colonic indigocarmine chromoendoscopy or standard colonoscopy with intensive inspection lasting ≥20 minutes. Size, histology, and numbers of polyps detected on each exam were recorded.

Results

Twenty-seven subjects were randomized to a second exam with chromoendoscopy and 23 underwent intensive inspection. Forty adenomas were identified on the first standard colonoscopies. The second colonoscopies detected 24 additional adenomas; 19 were found using chromoendoscopy and 5 using intensive inspection. Chromoendoscopy found additional adenomas in more subjects than intensive inspection (44% vs. 17%) and identified significantly more missed adenomas per subject (0.7 vs 0.2, p<0.01). Adenomas detected with chromoendoscopy were significantly smaller (mean size 2.66±0.97mm) and were more often right-sided. Chromoendoscopy was associated with more normal tissue biopsies and longer procedure times than intensive inspection. After controlling for procedure time, chromoendoscopy detected more adenomas and hyperplastic polyps compared with colonoscopy using intensive inspection alone.

Conclusions

Chromoendoscopy detected more polyps missed by standard colonoscopy than did intensive inspection. The clinical significance of these small missed lesions warrants further study.

Introduction

Most colorectal cancers (CRC) are believed to arise from adenomatous polyps(1, 2) and there is convincing evidence that colonoscopy with removal of colorectal adenomas reduces the risk of CRC.(1, 3) Although colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for detecting adenomatous polyps, studies have documented colonoscopy miss rates of 6–27% for adenomas. (4, 5) Studies employing back-to-back colonoscopy (4), comparing colonoscopy to CT colonography (6), and matching large CRC registries with endoscopic databases (7) have shown that adenomas, as well as cancers, can be missed during conventional colonoscopic exams. There continue to be cases of CRC diagnosed in individuals who had recent colonoscopic examinations in which no neoplastic lesions were seen (8), suggesting that missed lesions may be clinically important.

Chromoendoscopy, performed by spraying dye on the colorectal mucosa during colonoscopy, has been reported to improve detection of flat dysplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis (9), and of flat adenomas in screening and high risk populations. (10–17) However, previous randomized trials that have examined the sensitivity of chromoendoscopy for adenoma detection in average and moderate-risk subjects reached different conclusions about the clinical utility of spraying dye.(11, 12, 17) Critics of chromoendoscopy have argued that the technique is messy and time consuming and have proposed that the prolonged inspection time required to perform chromoendoscopy, and not the actual dye spraying, is the reason for the higher sensitivity for detecting polyps.

We conducted a randomized multi-center study to ascertain if chromoendoscopy was superior to intensive conventional endoscopy for detecting adenomas missed by standard colonoscopy in patients with a prior history of colorectal neoplasia. Our study was designed to control for the potential effect of procedure time on adenoma detection rate.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects were enrolled at five collaborating study centers associated with the Great-Lakes New England Clinical Epidemiology and Validation Center of the Early Detection Research Network (University of Michigan, Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Hospital, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Toronto, and the Tel Aviv Sourasky (Ichilov) Medical Center). Subjects were recruited from among patients scheduled to undergo surveillance colonoscopy. Eligible subjects were those with a prior history of CRC or ≥3 colorectal adenoma(s). Individuals under 18 years of age, with poor performance status, receiving active treatment for cancer, or using anticoagulant medications were ineligible for the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board or ethics board at each institution.

Study Procedure

All subjects underwent back-to-back colonoscopy exams, with a conventional colonoscopy followed immediately by a second endoscopy with either chromoendoscopy or intensive colonoscopy. Subjects were randomized after the cecum was reached during the second exam and randomization was performed in blocks sizes of two, stratified by study site. The endoscopist, study coordinator and endoscopy nurse were not made aware which randomization arm had been assigned until the cecum was reached during the second colonoscopy and the randomization envelope was opened.

Subjects provided informed consent and completed demographic and medical history questionnaires prior to colonoscopy. Subjects took a standardized preparation on the day prior to colonoscopy (magnesium citrate (12 oz) followed by either large volume (4 liter) polyethylene glycol colonic lavage, 1.5 oz of oral phosphosoda followed by 24 oz water (2 doses), or Visicol ™ tablet prep).

The first exam for all subjects was a standard colonoscopy with removal of all visualized polyps. On completion of the first colonoscopy, subjects were considered eligible to undergo the second exam if all of the following criteria were satisfied: the preparation was considered excellent, the first standard colonoscopy was completed in less than 30 minutes, the endoscopist considered the exam to be technically easy, and the endoscopist, study coordinator, and endoscopy nurse all agreed that the subject was comfortable and clinically able to immediately undergo a second procedure. Study participants were contacted 24 to 72 hours after their procedures to determine if they had experienced any adverse effects.

All 8 endoscopists participating in this study underwent training in chromoendoscopy technique and recognition of polyp morphology. Standard non-magnifying Olympus-160 or Pentax -160 colonoscopes (3 and 2 study sites, respectively) were used for all study procedures.

During each colonoscopy, a study coordinator recorded data from the endoscopic procedures, including the duration of each aspect of each procedure (time from endoscope insertion to visualization of cecal landmarks, time withdrawing from cecum to anal verge, and time spent performing polypectomy). The endoscopist assessed the location and size of each polyp as measured by placing an open standardized biopsy forceps (Bard 00823 C diameter 9.6mm inner dimension) adjacent to the polyp. Endoscopists were instructed to classify polyp morphology as polypoid or flat, with flat polyps defined as having height less than half of the diameter of the lesion. (10–12) All polyps were numbered and photographed before they were fully removed with standardized biopsy forceps or snares, according to standard clinical practice.

For subjects randomized to chromoendoscopy as their second exam, the entire colon was sprayed during withdrawal of the colonoscope with 0.2% indigo carmine solution with a standardized (Olympus pw-5v-1) spraying catheter and the mucosa was inspected in 10 cm segments. Each 20 ml of indigo carmine solution contained 1 ml of simethicone as an antifoaming agent. An average of 100 ml of solution was used per patient.

Subjects randomized to intensive inspection received a thorough examination of the colon without indigocarmine dye. Endoscopists were instructed to spend at least 20 minutes visualizing the colonic mucosa during withdrawal from the cecum, exclusive of time spent performing polypectomy.

All polyps seen on withdrawal of the endoscope during each of the two colonoscopic examinations were removed. Tissue removed from each visualized lesion was placed in its own jar, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and processed by the routine pathology procedures at the local institutions. The pathologic diagnosis was made by the pathologist at each of the five collaborating institutions as per routine practice. Based on the histopathologic diagnosis, lesions were categorized as adenomatous polyps, hyperplastic polyps, normal tissue or “other.”

Statistical Methods

The primary objective of this study was to compare the adenoma detection rates of chromoendoscopy and intensive inspection colonoscopy without dye spraying peformed after a standard colonoscopic examination. The study was designed as a multicenter randomized trial with 50 subjects. Polyp and biopsy counts were analyzed by means of generalized linear models (SAS PROC GENMOD, SAS Institute, Cary, NC), which assume that the number of lesions of any particular type identified in a given patient follows a Poisson distribution, with different means in each of the two study groups. Linear mixed models (SAS PROC MIXED) were used to compare the size of lesions between the treatment groups. Predictors in both patient-level and polyp-level models included clinical site, age, sex, race, smoking status, total number of previous colonoscopies and number of months since most recent colonoscopy. Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Subject Demographics

A total of 50 subjects completed the study. All subjects had a history of at least one prior colonoscopy with adenomatous polyps and/or colorectal cancer. After the first routine colonoscopy was completed and the cecum was reached during the second exam, 27 subjects were randomized to undergo chromoendoscopy and 23 subjects to intensive inspection colonoscopy without dye spraying. The discrepancy in the numbers of subjects in the two study arms was the result of the blocked randomization by study center. The baseline characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms with respect to baseline subject characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants by randomization arm

| Chromoendoscopy | Intensive Colonoscopy | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 27 | 23 |

| Mean Age (years) | 57.6 | 59.3 |

| Female | 14 (52%) | 7 (30%) |

| Non-White | 1 | 0 |

| Personal History of CRC | 2 (7%) | 3 (13%) |

| Family History of CRC | 9 (33.3%) | 5 (22%) |

| Number of Polyps on Previous Colonoscopies: | ||

| 1–2 | 13 (48%) | 12 (52%) |

| 3–5 | 4 (15%) | 3 (13%) |

| > 5 | 6 (22%) | 5 (22%) |

| Number of Previous Colonoscopies: | ||

| 1 | 7 (26%) | 7 (30.5%) |

| 2 | 6 (22%) | 4 (17.5%) |

| 3+ | 13 (48%) | 12 (52%) |

| Mean Time Since Last Colonoscopy (months*): | 18.8 | 26.3 |

| Range | 0–73 | 0–72 |

| History of Partial Colon Resection | 8(30 %) | 3(13%) |

| History of ever Smoking | 12 (44%) | 14 (61 %) |

| Current Smoking | 2 (7%) | 4 (17%) |

| Average number of alcoholic drinks/wk – (range) | 4.35 (0–42) | 5.48 (0–28) |

(There were no statistically significant (p<0.05) differences between arms in any of the listed variables.)

First Colonoscopy (Conventional Exam)

Prior to randomization, all subjects underwent an initial conventional colonoscopy. The average procedure time (from insertion of colonoscope to removal, minus time spent in removal of polyps) was 20.8 minutes. Twenty-five of 50 (50%) subjects had polyps on the first exam. Of the 78 lesions biopsied, 40 (51%) were adenomatous polyps, 21(27%) were hyperplastic polyps, 15 (19%) were normal tissue, one (1%) was a fragment of an adenoma, and one was patchy active colitis.

The characteristics of the first colonoscopy procedures are presented in Table 2 by randomization arm. There was no statistically significant difference in procedure time between subjects subsequently randomized to intensive inspection vs chromoendoscopy for their second exam, or in the number of subjects who had one or more polyps on the first exam (14 vs 11, respectively). Although there were no significant differences by arm in the total number of adenomas detected during the first standard colonoscopy exams (21 found in subjects in intensive inspection arm vs.19 in chromoendoscopy arm), more of the subjects with adenomas on the first standard exam were randomized to undergo intensive inspection for their second exam (11 vs. 6 assigned to chromoendoscopy, p=0.08).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Procedures (time, # of biopsies) by randomization arm

| First Colonoscopy | Second Colonoscopy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive Inspection Arm | Chromo-endoscopy Arm | Intensive Inspection Arm | Chromo-endoscopy Arm | |

| # Subjects | 23 | 27 | 23 | 27 |

| Procedure time (min) | 21.6±10.8 | 20.1±10.0 | 27.3±6.2 | 36.9±14.5 |

| # Subjects with biopsies | 15 (65%) | 12 (44%) | 12 (52%) | 19 (70%) |

| # Subjects with polyps | 14 (61%) | 11 (41%) | 8 (35%) | 17 (63%) |

| # Subjects with adenomas | 11 (48%) | 6 (22%) | 4 (17%) | 12 (44%) |

| # Biopsies per subject | 1.8±2.8 | 1.3±1.9 | 0.7±0.8 | 2.4±2.3 |

| # Polyps per subject | 1.4±2.5 | 1.0±1.8 | 0.4±0.7 | 1.3±1.4 |

| # Adenomas per subject | 0.9±1.9 | 0.7±1.7 | 0.2±0.5 | 0.7±1.0 |

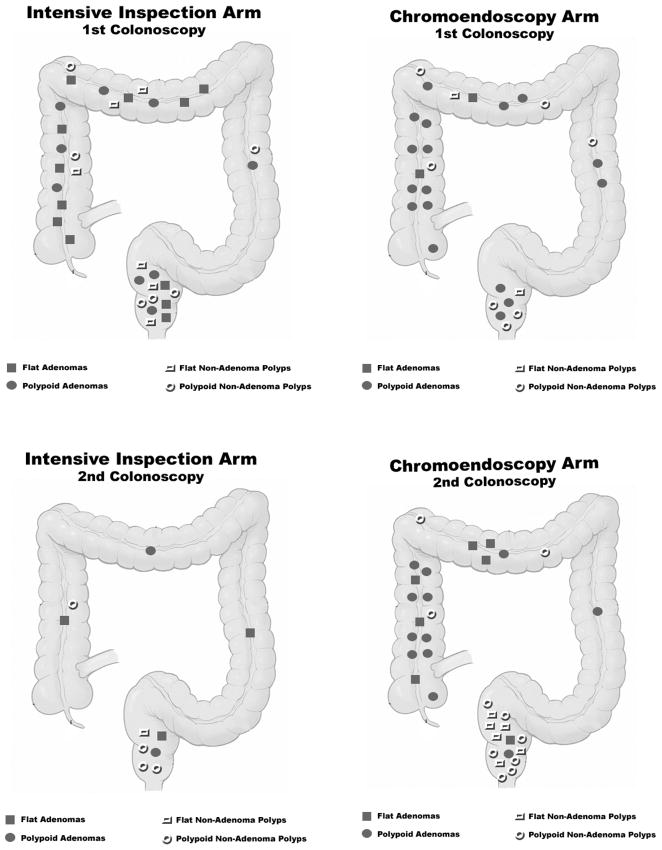

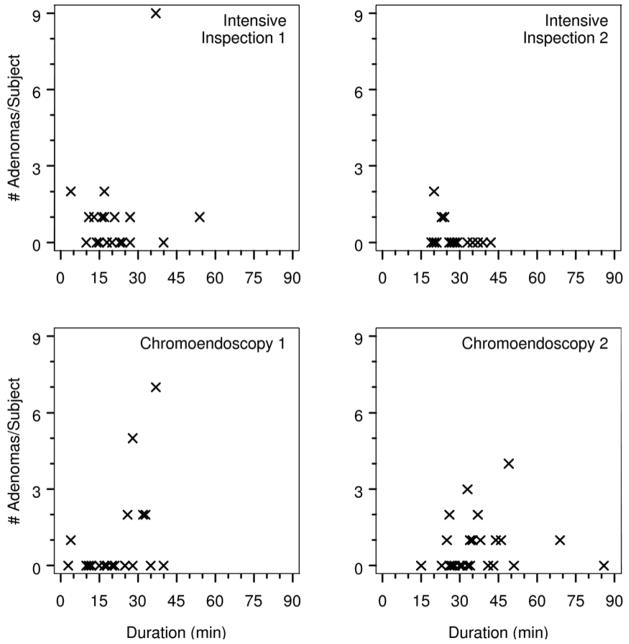

The characteristics of polyps found on the first exam are presented in Table 3 and polyp locations are shown in Figure 1. There was no statistically significant variation by arm in the sizes or location of polyps removed in the first colonoscopy, nor were there significant differences in distributions of adenomas, hyperplastic polyps and normal biopsies. Most adenomas found on the first exams were removed from the right colon proximal to the splenic flexure. Fourteen of 40 (35%) of the adenomas found on first exams were considered flat, with 12 of these found in the intensive inspection arm (p=0.002). There was no relationship between procedure time of the first colonoscopy and number of adenomas detected (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of polyps (mean sizes, counts) found at first and second colonoscopy by randomization arm

| First Colonoscopy Mean polyp size ± sd in mm (counts) | Second Colonoscopy Mean polyp size ± sd in mm (counts) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive Inspection Arm Subjects=23 | Chromo- endoscopy Arm Subjects=27 | Intensive Inspection Arm Subjects=23 | Chromo- endoscopy Arm Subjects=27 | |

| All Polyps | 3.09±2.74 (33) | 4.50±3.23 (28) | 2.80±1.03 (10) | 2.27±1.18 (35) |

| Adenomatous Polyps | 3.57±3.25 (21) | 4.68±3.59 (19) | 3.20±0.84 (5) | 2.66±0.97 (19) |

| Morphology | ||||

| Flat | 3.42±2.02 (12) | 1.00±0.00 (2) | 3.00±1.00 (3) | 2.36±1.18 (7) |

| Polypoid | 3.78±4.55 (9) | 5.12±3.55 (17) | 3.50±0.71 (2) | 2.83±0.83 (12) |

| Location | ||||

| Right-Sided | 3.72±3.65 (14) | 4.36±2.95 (14) | 3.00±0.00 (2) | 2.72±1.03 (16) |

| Left-Sided | 5.00± NC (1) | 3.50±0.71 (2) | 2.00± NC (1) | 3.00± NC (1) |

| Rectal | 3.00±2.61 (6) | 7.00±7.00 (3) | 4.00±0.00 (2) | 2.00±0.00 (2) |

| Hyperplastic Polyps | 2.25±1.22 (12) | 4.11±2.42 (9) | 2.40±1.14 (5) | 1.81±1.28 (16) |

| Morphology | ||||

| Flat | 2.33±1.03 (6) | 3.50±0.71 (2) | 4.00± NC (1) | 1.67±0.52 (6) |

| Polypoid | 2.17±1.47 (6) | 4.29±2.75 (7) | 2.00±0.82 (4) | 1.90±1.60 (10) |

| Location | ||||

| Right-Sided | 3.20±1.31 (5) | 5.25±3.30 (4) | 2.00± NC (1) | 3.00±1.73 (3) |

| Left-Sided | 1.00± NC (1) | 4.00± NC (1) | (0) | (0) |

| Rectal | 1.67±0.52 (6) | 3.00±1.15 (4) | 2.50±1.29 (4) | 1.54±1.05 (13) |

| Normal Samples | 1.5±1.31 (8) | 3.57±2.07 (7) | 2.00±0.00 (2) | 2.50±3.04 (22) |

| Location | ||||

| Right-Sided | 1.67±2.08 (3) | 3.40±2.07 (5) | (0) | 2.91±4.13 (11) |

| Left-Sided | (0) | (0) | (0) | 3.33±1.53 (3) |

| Rectal | 1.40±0.89 (5) | 4.00±3.83 (2) | 2.00±0.00 (2) | 1.63±1.06 (8) |

Mean±standard deviation (number of specimens); NC (not calculable)

Figure 1.

Distribution of polyps found on first (standard) and second (intensive inspection vs. chromoendoscopy) colonoscopies by randomization arm

Figure 2.

Plot of number of adenomas per subject vs procedure time (minutes) for first and second colonoscopies by randomization arm.

Intensive Inspection Colonoscopy

Twenty-three subjects were randomized to intensive inspection without dye spraying for their second colonoscopy, with a mean procedure time of 27.3 ± 6.2 minutes (range 19–42 minutes).

During the exams with intensive inspection, lesions were biopsied from 12/23 (52%) subjects. Eight subjects had polyps and 4 had adenomas (Table 2). Of the total of 12 lesions biopsied, 5 (41.5%) were adenomatous polyps, 5 (41.5%) were hyperplastic polyps, and 2 (17%) were normal tissue (Table 3).

The location of adenomatous polyps found on second colonoscopy with intensive inspection is shown in Figure 1. Three of the 5 (60%) adenomas were considered flat. There was no association between procedure time of the intensive inspection colonoscopy and the numbers of polyps and adenomas identified (Figure 2). Of 14 subjects with adenomas discovered at either the first routine or second intensive colonoscopy, 3 (21%) subjects had adenomas found only on the second colonoscopy. Adenomas removed during the intensive inspection colonoscopy were not significantly smaller than those obtained during the first standard colonoscopy (mean size 3.20±0.84mm vs 3.57±3.25mm, respectively)(Table 3).

Chromoendoscopy

Twenty-seven subjects were randomized to chromoendoscopy, with an average procedure time of 36.9±14.5 minutes (range 15–86 minutes). During the chromoendoscopy examination, lesions were biopsied from 19/27 (70%) subjects. Seventeen subjects had polyps and 12 had adenomas (Table 2). Of the total of 57 lesions biopsied, 19 (32%) were adenomatous polyps, 16 (27%) were hyperplastic polyps, two were mucosal polyps, one was patchy active colitis and 22 (37%) were normal tissue (Table 3).

Of the 19 adenomas found during chromoendoscopy exams, 16 (84%) were removed from the right colon, one (5%) from the left colon and two (11%) from the rectum (Figure 1). Seven (37%) of the adenomas were considered flat and six of the flat adenomas were located in the right colon. There was no association between the duration of the chromoendoscopy procedure and the numbers of polyps and adenomas identified during the exam (Figure 2).

Of 13 subjects randomized to chromoendoscopy who had adenomas discovered at either colonoscopy, 7 (54%) had adenomas found only during the second exam. Adenomas obtained during chromoendoscopy were significantly smaller than those obtained during the first examination (mean size 2.66±0.97mm vs 4.68±3.59mm, respectively)(Table 3).

Intensive Inspection Colonoscopy versus Chromoendoscopy

Chromoendoscopy took significantly longer than intensive inspection, with an average procedure time of 36.9±14.5 minutes versus 27.3±6.2 minutes, respectively (p<0.01). Subjects randomized to chromoendoscopy had more biopsies on their second exams (2.4 ±2.3 biopsies/subject compared with 0.7 ±0.8 for intensive inspection), and chromoendoscopy detected more hyperplastic polyps (16 vs 4 in intensive inspection), and more adenomas (19 vs 4 in intensive inspection) (Tables 2 and 3). Although chromoendoscopy exams yielded 22 biopsies that were normal tissue, the percentages of biopsies that were normal tissue were similar in the standard colonoscopy, intensive inspection and chromoendoscopy examinations. There were no adverse events reports reported for any of the 50 subjects.

Twelve of 27 (44%) subjects in the chromoendoscopy arm and 4 of 23 (17%) in the intensive inspection arm had additional adenomas found during the second colonoscopy (Table 2). Overall, 24 of 64 (38%) adenomas were found on second exams. The adenomas detected on the second exams were significantly smaller than those removed during the first colonoscopy; however, the size did not significantly differ between the intensive inspection and chromoendoscopy arms (Table 3). None of the polyps detected during the second colonoscopies had features of high-grade dysplasia.

In multivariate analysis controlling for procedure time and study center, use of chromoendoscopy was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of finding one or more additional adenomas on the second exam than intensive inspection (p=0.04).

Discussion

We designed this randomized trial of back-to-back colonoscopies to determine whether chromoendoscopy is better than intensive inspection without dye spraying for detecting small adenomatous lesions that might be missed during a routine colonoscopy. We found that chromoendoscopy doubled the adenoma yield after a standard colonoscopy and detected significantly more adenomas than intensive inspection exams performed without using dye. Chromoendoscopy identified additional adenomas in 44% of subjects, and changed management for 26% of subjects (n=7) who would have been misclassified as “adenoma free” after the first standard colonoscopy. Although chromoendoscopy exams lasted nearly 10 minutes longer than exams using intensive inspection without dye spraying, after controlling for procedure time through study design and multivariate analysis, our data support that the increase in adenoma detection seen with chromoendoscopy is independent of inspection time.

Overall, 38% of adenomas found in our subjects were detected on the second exams, suggesting that a single conventional colonoscopy may miss approximately 1 of every 3 adenomas present. The conventional exam missed half of the total adenomas in subjects who underwent chromoendoscopy, a much higher miss rate than the 26–27% for adenomas 1–5mm previously reported in studies of tandem exams using conventional colonoscopy. (4, 5) Most of the adenomas found on our second exams were small (<5mm) and none met definitions for advanced adenomas based on size or histology. Even so, 75% (18/24) of the missed adenomas were located in the right colon and 42% (10/24) had a flat morphology, characteristics that may be associated with a more aggressive natural history. (18–20)

Several recent European studies have also reported that chromoendoscopy detects more, albeit diminutive, colorectal adenomas. (11, 12, 17) While our findings are similar, it is important to note that our study is the first multicenter North American trial to examine the utility of chromoendoscopy for adenoma detection. Furthermore, our study design was unique in its use of randomized tandem colonoscopies to compare chromoendoscopy to a time- intensive conventional colonoscopy control. Our findings support that dye spraying improves adenoma yield and that results using a standard chromoendoscopy technique are generalizeable.

We acknowledge our study has several limitations. The chromoendoscopy exams lasted on average 10 minutes longer than the intensive inspection exams. Recent reports have demonstrated an association between inspection time and adenoma detection rates(21), and in designing our study we included the intensive inspection arm to control for time, considering that a 20 minute inspection would greatly exceed the threshold of 6 minutes recommended by expert opinion.(22) In examining our data we found no association between procedure time and number of adenomas detected and after controlling for time in the multivariate analysis the effect of chromoendoscopy remained statistically significant. This supports our conclusion that the dye spraying, and not longer inspection time, is responsible for the higher sensitivity of chromoendoscopy for adenoma detection.

This was a small study and, despite blinded randomization, there were differences among subjects by randomization arm. However, none of these differences were statistically significant and they are unlikely to completely explain the increased adenoma yield with chromoendoscopy. While endoscopists could not be truly blinded to procedure type, they were not aware of which randomization arm had been assigned until after the first colonoscopy was completed, and there were no differences in procedure characteristics of the first colonoscopy by randomization arm (procedure time, number of biopsies) to suggest differential bias in adenoma detection.

We performed all of the exams using standard colonoscopes, rather than high definition or magnification colonoscopes, since we believed this technique would be more exportable to other clinical practice settings; however there are data showing HD/magnification endoscopes increase sensitivity of chromoendoscopy, so our results may underestimate the effect of chromoendoscopy. We recognize that since all study subjects had prior history of colorectal cancer or adenomas, the adenoma yield of chromoendoscopy would probably be lower in an average risk population.

Our results demonstrate that chromoendoscopy improves detection of colorectal adenomas missed by conventional colonoscopy independent of inspection time. Our findings from this North American multicenter study are consistent with reports from randomized trials conducted in European centers with expertise in chromoendoscopy. (11, 12, 17) However, all but one of those studies (11) concluded that since most of the adenomas detected by chromoendoscopy were small (<5mm), there was insufficient evidence to support the routine use of chromoendoscopy in the clinical setting. Still, studies indicate flat adenomas, which can be difficult to see during conventional white-light colonoscopy, are 10 times more likely than polypoid lesions to contain invasive carcinoma (20) and 7–15% of small adenomas (5–10mm) demonstrate advanced histology(18, 19). Although it is believed that cancers that arise in the interval between colonoscopic exams may be the result of missed lesions, we currently have no way of knowing if any of the additional lesions detected by chromoendoscopy would be clinically significant.

Recent reports have recommended that chromoendoscopy should be used for routine screening for flat neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis.(9, 23–25) As there are limited data regarding the natural history of small flat adenomas, the utility of chromoendoscopy or other new endoscopic modalities for CRC screening in average and moderate-risk individuals will ultimately depend on the biological significance of small flat lesions missed by conventional colonoscopy.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: NCI grant CA 86400 Early Detection Research Network

References

- 1.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(27):1977–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61(5):759–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meagher AP, Stuart M. Does colonoscopic polypectomy reduce the incidence of colorectal carcinoma? Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64(6):400–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb02238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, et al. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(1):24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, Dekker E. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(2):343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2191–200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bressler B, Paszat LF, Vinden C, Li C, He J, Rabeneck L. Colonoscopic miss rates for right-sided colon cancer: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(2):452–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson DJ, Greenberg ER, Beach M, et al. Colorectal cancer in patients under close colonoscopic surveillance. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):34–41. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, et al. Methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(4):880–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saitoh Y, Waxman I, West AB, et al. Prevalence and distinctive biologic features of flat colorectal adenomas in a North American population. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(7):1657–65. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Slater R, Sanders DS, Brown S. Detecting diminutive colorectal lesions at colonoscopy: a randomised controlled trial of pan-colonic versus targeted chromoscopy. Gut. 2004;53(3):376–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Rhun M, Coron E, Parlier D, et al. High resolution colonoscopy with chromoscopy versus standard colonoscopy for the detection of colonic neoplasia: a randomized study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(3):349–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lecomte T, Cellier C, Meatchi T, et al. Chromoendoscopic colonoscopy for detecting preneoplastic lesions in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(9):897–902. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaramillo E, Watanabe M, Slezak P, Rubio C. Flat neoplastic lesions of the colon and rectum detected by high-resolution video endoscopy and chromoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(2):114–22. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rembacken BJ, Fujii T, Cairns A, et al. Flat and depressed colonic neoplasms: a prospective study of 1000 colonoscopies in the UK. Lancet. 2000;355(9211):1211–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Adam I, et al. A prospective clinicopathological and endoscopic evaluation of flat and depressed colorectal lesions in the United Kingdom. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(11):2543–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapalus MG, Helbert T, Napoleon B, Rey JF, Houcke P, Ponchon T. Does chromoendoscopy with structure enhancement improve the colonoscopic adenoma detection rate? Endoscopy. 2006;38(5):444–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butterly LF, Chase MP, Pohl H, Fiarman GS. Prevalence of clinically important histology in small adenomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(3):343–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Brien MJ, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, et al. The National Polyp Study. Patient and polyp characteristics associated with high-grade dysplasia in colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):371–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soetikno RM, Kaltenbach T, Rouse RV, et al. Prevalence of nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic and symptomatic adults. Jama. 2008;299(9):1027–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2533–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rex DK. Maximizing detection of adenomas and cancers during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2866–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurlstone DP, McAlindon ME, Sanders DS, Koegh R, Lobo AJ, Cross SS. Further validation of high-magnification chromoscopic-colonoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(1):376–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farraye FA, Schroy PC., 3rd Chromoendoscopy: a new vision for colonoscopic surveillance in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(1):323–5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.059. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiesslich R, Neurath MF. Chromoendoscopy: an evolving standard in surveillance for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10(5):695–6. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]