Abstract

AIM: To determine the predictive factors for early aspiration in liver abscess.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis of all patients with liver abscess from 1995 to 2004 was performed. Abscess was diagnosed as amebic in 661 (68%) patients, pyogenic in 200 (21%), indeterminate in 73 (8%) and mixed in 32 (3%). Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to determine predictive factors for aspiration of liver abscess.

RESULTS: A total of 966 patients, 738 (76%) male, mean age 43 ± 17 years, were evaluated: 540 patients responded to medical therapy while adjunctive percutaneous aspiration was performed in 426 patients. Predictive factors for aspiration of liver abscess were: age ≥ 55 years, size of abscess ≥ 5 cm, involvement of both lobes of the liver and duration of symptoms ≥ 7 d. Hospital stay in the aspiration group was relatively longer than in the non aspiration group. Twelve patients died in the aspiration group and this mortality was not statistically significant when compared to the non aspiration group.

CONCLUSION: Patients with advanced age, abscess size > 5 cm, both lobes of the liver involvement and duration of symptoms > 7 d were likely to undergo aspiration of the liver abscess, regardless of etiology.

Keywords: Liver abscess, Aspiration and liver abscess, Needle aspiration and liver abscess, Amebic liver abscess, Pyogenic liver abscess, Liver abscess and management

INTRODUCTION

Liver abscess, particularly due to amebiasis, is an important clinical problem in tropical regions of the world and accounts for a high number of hospital admissions[1–5]. It is usually an easily treatable condition with good clinical outcomes. There is however potential for morbidity and even mortality if proper and timely treatment is not provided[6–9]. The standard treatment of liver abscess is the use of appropriate antibiotics and supportive care. Needle aspiration can be used as an additional mode of therapy and has been promoted by some authors for routine use in the treatment of uncomplicated liver abscess. It is suggested that needle aspiration can improve response to antibiotic treatment, reduce hospital stay and the total cost of treatment[10–12]. Although ultrasound guided needle aspiration is fairly safe, it is nonetheless an invasive procedure requiring the passage of a wide bore needle into a highly vascular organ, and can be associated with the risk of bleeding. Needle aspirations, especially at the time of intervention has therefore remained a debatable issue and it seems important to determine its possible role in the treatment of liver abscess[13–16].

We have used a large database of patients admitted to hospital with liver abscess in order to determine the factors associated with the likelihood of liver abscess aspiration in the treatment of patients with uncomplicated liver abscess.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

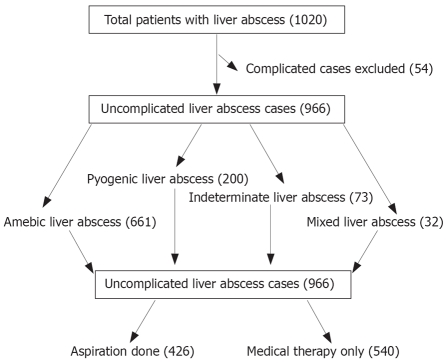

Medical records of all patients admitted to our hospital with liver abscess over a ten-year period (Jan. 1995 to Dec. 2004) were identified using the International classification of diseases 9th revision with clinical modification (ICD-9-CM-USA) and reviewed retrospectively. Patients with complicated liver abscess, generally due to rupture of abscess, were excluded from this analysis, as the indications for needle aspiration in these patients are rather different (Figure 1). Diagnosis of liver abscess was based upon clinical history and abdominal ultrasound or CT scan findings. The following data was collected in all the patients who were diagnosed with uncomplicated liver abscess: demographic information, chief complaint, duration of fever or abdominal pain, associated illnesses, malignancy and history of biliary surgery or other procedures. Results of laboratory investigations and imaging studies done at the time of admission were recorded as were the clinical course of disease, modalities of treatments used and outcome of the patients.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the patients with liver abscess and treatment received.

Patients with uncomplicated (non-ruptured) liver abscess were underwent to the following investigations: Complete blood counts, imaging by ultrasound, Indirect Hem-agglutination Assay (IHA) for amebiasis, blood culture and pus culture if the abscess was aspirated. IHA was done with serology reagent “Cellognost Amebiasis” supplied by (Dade Behring Marburg GmbH Germany) and a titer of ≥ 1:128 was taken as diagnostic for amebic liver abscess, as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Based upon the results of these investigations, patients with liver abscess were categorized into four groups according to the following criteria: (1) Amebic liver abscess (ALA): IHA titer ≥ 1:128 with negative blood or pus culture. (2) Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA): IHA titer < 1:32 with or without positive blood and/or pus culture. (3) Mixed liver abscess (MLA): IHA titer ≥ 1:128 with positive blood and/or pus culture and (4) Indeterminate liver abscess (ILA): IHA titer between 1:32 and 1:128 with negative blood or pus culture. According to our usual practice, patients were started on standard treatment of liver abscess and if no clinical response was observed within three days, therapeutic percutaneous needle aspiration was carried out at the discretion of the treating physician. Needle aspiration was done under local anesthesia and ultrasound guidance without catheter drainage and the procedure was repeated in 3-4 d if optimal response was not obtained. Antibiotics were continued for 10-14 d for ALA, 4-6 wk for PLA and mixed infection and 2-6 weeks for indeterminate abscess.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was done for demographic, clinical and radiographic features and results were presented as mean ± SD for quantitative variables and number (percentage) for qualitative variables. In univariate analyses, differences in proportions for the group of patient underwent to needle aspiration and no aspiration was done by using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test where appropriate. One-way analysis of variance and independent samples t-test were used to assess the difference of means for contrasts of continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was done and factors associated with likelihood of abscess aspiration were identified.

RESULTS

A total of 1020 patients with liver abscess were admitted during the study period. Fifty four patients with complicated liver abscess were excluded from the study and 966 patients with uncomplicated liver abscess were evaluated (Figure 1). The mean age was 43 ± 17 years and 738 (76%) were males. The abscess was diagnosed as amebic (ALA) in 661 (68%), pyogenic (PLA) in 200 (21%), indeterminate (ILA) in 73 (8%) and mixed (MLA) in 32 (3%) patients. Clinical features of the patients in different types of liver abscess are presented in Table 1. Five hundred and forty patients responded to medical therapy alone; adjunctive percutaneous aspiration was performed in 426 patients. Demographic, clinical and laboratory features of the two groups are compared in Tables 2, 3, 4. There were significant differences between aspiration and non aspiration groups for many covariates.

Table 1.

Clinical features of the patients with different types of liver abscess n (%)

| Characteristics | Amebic | Pyogenic | Mixed | Indeterminate | P |

| abscess | abscess | abscess | abscess | value | |

| (n = 661) | (n = 200) | (n = 32) | (n = 73) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 568 (86) | 158 (79) | 27 (84) | 66 (90) | 0.06 |

| Female | 93 (14) | 42 (21) | 5 (16) | 7 (10) | |

| Age | |||||

| < 55 yr | 471 (71) | 146 (73) | 25 (78) | 52 (71) | |

| ≥ 55 yr | 190 (29) | 54 (27) | 7 (22) | 21 (29) | 0.83 |

| Duration of symptoms1 | |||||

| ≥ 7 d | 453 (69) | 136 (68) | 24 (75) | 47 (64) | 0.752 |

| < 7 d | 208 (32) | 64 (32) | 8 (25) | 26 (36) | |

| Jaundice (%) | |||||

| No | 534 (81) | 170 (85) | 26 (81) | 64 (88) | |

| Yes | 126 (19) | 30 (15) | 6 (19) | 9 (12) | 0.341 |

| Tender hepatomegaly | |||||

| Yes | 553 (84) | 179 (90) | 26 (81) | 57 (78) | 0.085 |

| No | 107 (16) | 21 (10) | 6 (19) | 16 (22%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 546 (83) | 166 (83) | 25 (78) | 60 (82) | 0.925 |

| Yes | 115 (17) | 34 (17) | 7 (22) | 13 (18) | |

| Treatment | |||||

| Aspiration not done | 375 (57) | 109 (54) | 12 (37) | 44 (60) | 0.151 |

| Aspiration done | 286 (43) | 91 (46) | 20 (63) | 29 (40) | |

| Patient outcome | |||||

| Alive | 649 (98) | 192 (96) | 31 (97) | 72 (99) | |

| Died | 12 (2) | 8 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.352 |

Fever or abdominal pain.

Table 2.

Clinical features of patients with liver abscess

| Characteristics | Aspiration group (n = 426) | Non aspiration group (n = 540) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 365 (85.7) | 454 (84.1) | 1.13 | 0.79-1.61 | 0.490 |

| Female | 61 (14.3) | 86 (15.9) | 1.00 | ||

| Age | |||||

| < 55 yr | 282 (66.0) | 412 (76.0) | 1.00 | 1.2-2.2 | 0.001 |

| ≥ 55 yr | 144 (34.0)a | 128 (24.0) | 1.60 | ||

| Duration of symptoms1 (n%) | |||||

| < 7 d | 111(26.1) | 195 (36.1) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 7 d | 315 (73.9)a | 345 (63.9) | 1.60 | 1.21-2.11 | 0.001 |

| Jaundice (n%) | |||||

| Yes | 91 (21.4)a | 80 (14.8) | 1.55 | 1.18-2.17 | 0.009 |

| No | 335 (78.6) | 459 (85.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus (n%) | |||||

| Yes | 70 (16.4) | 99 (18.3) | 0.87 | 0.62-1.22 | 0.440 |

| No | 356 (83.6) | 441 (81.7) | 1.00 | ||

| Patient outcome (n%) | |||||

| Alive | 414 (97.2) | 530 (98.1) | 1.00 | 0.65-3.59 | 0.320 |

| Died | 12 (2.8) | 10 (1.9) | 1.53 | ||

| Hospital stay (n%) | |||||

| < 5 d | 126 (29.6) | 265 (49.1) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 5 d | 300 (70.4)a | 275 (50.9) | 2.29 | 1.75-2.99 | 0.001 |

Variable compared to reference category (OR = 1),

P < 0.05;

Fever or abdominal pain.

Table 3.

Laboratory features of the patients with liver abscess

| Characteristics (mean ± SD) | Aspiration group (n = 426) | Non aspiration group (n = 540) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.55 ± 3.4 | 1.86 ± 2.2 | 1.090 | 1.04-1.15 | 0.001 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 81.29 ± 98.87 | 66.18 ± 75.9 | 1.002 | 1.000-1.004 | 0.010 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 18.45 ± 141.3 | 86.8 ± 117.2 | 1.002 | 0.001-1.003 | 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 2.24 ± 0.50 | 2.42 ± 0.6 | 0.590 | 0.44-0.80 | 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.37 ± 1.20 | 1.25 ± 0.8 | 1.130 | 0.99-1.28 | 0.070 |

| Leukocyte counts (103/mm3) | 20.09 ± 9.61 | 18.67 ± 8.03 | 1.010 | 1.004-1.030 | 0.010 |

| Platelet counts (103/mm3) | 357.69 ± 162.40a | 328.33 ± 143.98 | 1.001 | 1.000-1.002 | 0.004 |

Variable compared to reference category (OR = 1),

P < 0.05; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

Table 4.

Radiological features of patients with liver abscess (%)

| Characteristics | Aspiration group (n = 426) | Non aspiration group (n = 540) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

| No. of abscess | |||||

| Single abscess | 303 (71.1) | 434 (80.4) | 1.00 | ||

| Multiple abscesses | 123 (28.9)a | 106 (19.6) | 1.66 | 1.23-2.24 | 0.001 |

| Site of lobe involvement | |||||

| Right lobe | 301 (70.7) | 415 (76.9) | 0.97 | 0.67-1.40 | |

| Left lobe | 59 (13.8) | 79 (14.6) | 1.00 | - | 0.010 |

| Both lobes | 66 (15.5)a | 46 (8.4) | 1.92 | 1.15-3.18 | |

| Presence of gallstones | |||||

| Yes | 8 (1.9)a | 11 (2.0) | 0.92 | ||

| No | 418 (98.1) | 529 (98.0) | 1.00 | 0.36-2.30 | 0.860 |

| Chest radiograph | |||||

| Normal | 235 (55.2) | 334 (61.9) | 1.00 | ||

| Abnormal1 | 191 (44.8)a | 206 (38.1) | 1.31 | 1.01-1.70 | 0.030 |

| Size of abscess | |||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 121 (28.4) | 209 (38.7) | 1.00 | ||

| > 5 cm | 305 (71.6)a | 331 (61.3) | 1.59 | 1.21-2.09 | 0.001 |

Raised right hemi diaphragm, pleural effusion, and right lung base atelactasis. Variable compared to reference category (OR = 1),

P < 0.05.

In the aspiration group, more patients were older than 55 years (OR = 1.008; 95% CI = 1.0-1.01), duration of symptoms was more than 7 d (OR=1.60; 95% CI = 1.21-2.11), they were more likely to be jaundiced (OR = 1.55; 95% CI = 1.18-2.17), have tender hepatomegaly (OR = 0.68; 95% CI = 0.48-0.97) and hospital stay of more than 5 d (OR = 2.99; 95% CI = 1.75-2.99), as compared to the non-aspiration group (Table 2).

In the laboratory features the meaningful predictors of aspiration were elevated total bilirubin (OR = 1.09; 95% CI = 1.04-1.15), ALT (OR = 1.002; 95% CI = 1.0-1.004), alkaline phosphatase (OR = 1.002; 95% CI = 1.001-1.003), total leukocyte count (OR = 1.01; 95% CI = 1.004-1.03) and platelet count (OR = 1.001; 95% CI = 1.0-1.002), whereas relatively low serum albumin (OR = 0.59; 95% CI = 0.44-0.80) was found in the aspiration group as compared to the non aspiration group (Table 3).

The aspiration group, when compared with the non-aspiration group, was also found to have more patients with abscess sizes larger than 5 cm (OR = 1.59; 95% CI = 1.21-2.09), multiple abscesses (OR = 1.66; 95% CI = 1.23-2.24), involvement of both lobes of the liver (OR = 1.92; 95% CI = 1.15-3.18) and abnormal chest X-rays (OR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.01-1.70) (Table 4).

Using multiple logistic regression, independent predictors for aspiration of liver abscess were age > 55 years, (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.2-2.2), size of abscess more than 5 cm (OR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.2-2.09), both lobes of the liver involvement (OR = 2.2, 95% CI = 1.5-3.4) and duration of symptoms lasting more than seven days (OR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.2-2.1) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Independent predictors for aspiration of liver abscess

| Factor | Coefficient | Adjusted | 95% CI for | Wald |

| odds ratio | adjusted odds ratio | P-value | ||

| Age | ||||

| < 55 yr | 0 | 11 | ||

| ≥ 55 yr | 0.5135 | 1.6 | 1.2-2.2 | 0.001 |

| Size of abscess | ||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 0 | 11 | ||

| > 5 cm | 0.5324 | 1.6 | 1.2-2.09 | 0.001 |

| Location of abscess | ||||

| One lobe | 0 | 11 | ||

| Both lobes | 0.7958 | 2.2 | 1.5-3.4 | 0.001 |

| Duration of symptoms | ||||

| < 7 d | 0 | 11 | ||

| ≥ 7 d | 0.4542 | 1.6 | 1.2-2.1 | 0.001 |

The parameter coefficient, adjusted odds ratio, 95% CI and Wald P-value, were estimated using multiple logistic regression.

Reference category.

The number of abscesses ranged from 1-6 (median 2). None of the patients with uncomplicated liver abscess required surgery. In 403 (42%) patients, only one aspiration session was done and in 23 (2%) patients, 2-3 aspiration sessions were done before full recovery.

Twelve patients died in the aspiration group, although this mortality was not statistically significant when compared with the non aspiration group (Table 2). No deaths occurred as a direct complication of the needle aspiration.

DISCUSSION

The use of needle aspiration in the treatment of uncompli-cated liver abscess remains a debatable issue. Although most of these patients respond to antibiotics and supportive care, a significant number eventually require needle aspiration which is generally done at a later stage, while medical therapy alone is considered as inadequate, resulting in an extended hospital stay[17–21].

An early decision regarding aspiration of liver abscess is therefore important as it is likely to reduce the length of hospital stay and hence the cost of treatment. On the basis of patient characteristics at the time of presentation, using a large data set, we have identified some factors that are associated with aspiration of liver abscess irrespective of the underlying etiology but we were unable to evolve a model for aspiration with good power.

Most patients in this series also recovered completely on appropriate antibiotics and supportive care. However in a substantial number of patients, percutaneous needle aspiration was additionally done for complete recovery. Based upon a comparative analysis between the two groups, patients who underwent aspiration were older, had larger or multiple abscesses and longer duration of symptoms than patients who recovered completely on medical therapy alone. Underlying etiology of amebic, pyogenic, mixed or indeterminate infection was not found to be a determinant for aspiration.

This study also reflects the difficulties sometimes faced by clinicians in determining the etiology of liver abscess. In this series, 68% of the 966 patients were diagnosed to have ALA, reflecting the burden of amebic infection in tropical regions of the world[3].

The diagnosis of ALA is usually based on clinical and radiological features along with a positive IHA Entameba titer[1–3]. However none of these features are diagnostic and, in clinical practice, confusion can often arise as to the accurate diagnosis of ALA. For example a solitary abscess in the right lobe of the liver is considered to be highly suggestive of ALA[3,6,22], which was true for 79% of ALA patients in this study. However a predominantly single abscess involving the right lobe was also seen in 68% of patients with PLA, suggesting that the presence of a single right lobe abscess should not exclude the diagnosis of PLA even in areas endemic for ALA. Similarly, although multiple abscesses involving both lobes were present more commonly in patients with PLA[23–25], they were also seen in 21% of patients with ALA.

The IHA Entameba titer is used to confirm the diagnosis of ALA. A high titer of IHA in invasive amebiasis is seen due to prolonged antigenic stimulation of absorbed liver abscess material[2]. However some issues should be considered when amoebic IHA is used in clinical practice. There is firstly the problem inherent in any serological assay, and that is the time lag required for the test to become positive so that the first reading may not achieve diagnostic values[2]. Secondly, in an endemic area, the appropriate cut off value for a positive test needs to be defined, keeping in mind the background positivity due to repeated (sub clinical) exposures[1–3]. Titers of ≥ 1:128 were considered as diagnostic for ALA in this study, based upon the manufacturer’s recommendations and current literature[1,2]. However the higher the titer, the better is its diagnostic value considered.

Patients with pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) in this study has shown some differences in their clinical profile compar-ed with other reported series; they were younger (mean age of 43 ± 17 years) and the etiology was predominantly cryptogenic[18,19].

Although gallstones were present more frequently in PLA compared to patients with ALA, they were not associated with ascending cholangitis in the present series as reported previously[15,16]. The reasons for these differences are not clear. However other reports also show series of patients with PLA where the primary focus of infection was not known[26–28].

Mixed abscess in this series comprised of 32 (3%), similar to the 4%-5%. Prevalence reported in the literature[20]. Mixed abscesses are basically ALA with secondary bacterial infection and their outcome was similar to ALA in the current series (Table 5) while in some studies mixed abscess has high mortality[29,30].

Patients with indeterminate liver abscess behaved like ALA as regards response to treatment and outcome of disease. However the IHA titer failed to rise, even on successive testing in some cases. This may be due to a technical failure of the serological tests in these patients for various reasons, including a depressed immune status.

In conclusion, based upon a retrospective analysis of a large series of patients, we have found that if the patient with liver abscess is older in age, the abscess is more than 5 cm in size, both lobes of the liver are involved and the duration of symptoms is more than a week, then these patients are more likely to undergo percutaneous aspiration regardless of the etiology of abscess. A prospective study to validate these observations is underway, and if found accurate, it is likely to have an impact on cost effective approaches and quality of life in the management of such patients.

COMMENTS

Background

Liver abscess, especially the amebiasis is more prevalent in the tropical region of the world due to poor hygiene and sanitation. The standard treatment of liver abscess is the use of appropriate antibiotics and supportive care. Needle aspiration can be used as an additional mode of therapy and has been promoted by some authors for routine use in the treatment of liver abscess. It is suggested that needle aspiration can improve responses to antibiotic treatment, reduce hospital stay and the total cost of treatment. Needle aspirations, especially at the time of intervention has therefore remained a debatable issue and it seems important to determine its possible role in the treatment of liver abscess.

Research frontiers

On the basis of a large dataset, we determine the factors associated with the likelihood of liver abscess aspiration in the treatment of patients with uncomplicated liver abscess.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Based upon a retrospective analysis of a large series of patients, we have found that if the patient with liver abscess is older in age, abscess is more than 5 cm in size, both lobes of the liver are involved and duration of symptoms is more than a week then these patients are more likely to undergo percutaneous aspiration regardless of the etiology of abscess.

Applications

A prospective study to validate these observations are underway, and if found accurate, it is likely to have an impact on the cost effectiveness and quality of life in the management of such patients.

Peer review

This paper by Khan et al reports information on predictive factors for aspiration in liver abscess. It is a retrospective study based on a very large series of cases. A number of factors showed predictive values for aspiration in liver abscess. Although retrospective, this study is well-designed and performed and the findings are sound for the clinical arena.

Acknowledgments

Juanita Hatcher, Director Statistical Support Unit, Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, provided valuable comments regarding statistical analysis of the data.

Peer reviewer: Pietro Invernizzi, Dr, Division of Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Surgery, Dentistry, San Paolo School of Medicine, University of Milan, Via Di Rudinfi 8, 20142 Milan, Italy

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Roberts SE E- Editor Liu Y

References

- 1.Khan MH, Qamar R, Shaikh Z. Serodiagnosis of amoebic liver abscess by IHA method. J Pak Med Assoc. 1989;39:262–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson M, Healy GR, Shabot JM. Serologic testing for amoebiasis. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahsan T, Jehangir MU, Mahmood T, Ahmed N, Saleem M, Shahid M, Shaheer A, Anwer A. Amoebic versus pyogenic liver abscess. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1032–1038. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lodhi S, Sarwari AR, Muzammil M, Salam A, Smego RA. Features distinguishing amoebic from pyogenic liver abscess: a review of 577 adult cases. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:718–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA Jr. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565–1573. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu SC, Ho SS, Lau WY, Yeung DT, Yuen EH, Lee PS, Metreweli C. Treatment of pyogenic liver abscess: prospective randomized comparison of catheter drainage and needle aspiration. Hepatology. 2004;39:932–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molle I, Thulstrup AM, Vilstrup H, Sorensen HT. Increased risk and case fatality rate of pyogenic liver abscess in patients with liver cirrhosis: a nationwide study in Denmark. Gut. 2001;48:260–263. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes MA, Petri WA Jr. Amebic liver abscess. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:565–582, viii. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandon A, Jain AK, Dixit VK, Agarwal AK, Gupta JP. Needle aspiration in large amoebic liver abscess. Trop Gastroenterol. 1997;18:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ch Yu S, Hg Lo R, Kan PS, Metreweli C. Pyogenic liver abscess: treatment with needle aspiration. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:912–916. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(97)80223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenstein AJ, Barth J, Dicker A, Bottone EJ, Aufses AH Jr. Amebic liver abscess: a study of 11 cases compared with a series of 38 patients with pyogenic liver abscess. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:472–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosoff L Sr. Amebic abscesses of the liver. In: Davis C, editor. Textbook of Surgery; The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice, 10th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1977. p. 1214. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma MP, Dasarathy S. Amoebic liver abscess. Trop Gastroenterol. 1993;14:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu KM, Fan ST, Lai EC, Lo CM, Wong J. Pyogenic liver abscess. An audit of experience over the past decade. Arch Surg. 1996;131:148–152. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430140038009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moazam F, Nazir Z. Amebic liver abscess: spare the knife but save the child. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petri WA Jr, Singh U. Diagnosis and management of amebiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1117–1125. doi: 10.1086/313493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna S, Chaudhary D, Kumar A, Vij JC. Experience with aspiration in cases of amebic liver abscess in an endemic area. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:428–430. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanley SL Jr. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung YF, Tan YM, Lui HF, Tay KH, Lo RH, Kurup A, Tan BH. Management of pyogenic liver abscesses-percutaneous or open drainage? Singapore Med J. 2007;48:1158–1165; quiz 1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conter RL, Pitt HA, Tompkins RK, Longmire WP Jr. Differentiation of pyogenic from amebic hepatic abscesses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;162:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johannsen EC, Sifri CD, Madoff LC. Pyogenic liver abscesses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:547–563, vii. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou FF, Sheen-Chen SM, Chen YS, Chen MC. Single and multiple pyogenic liver abscesses: clinical course, etiology, and results of treatment. World J Surg. 1997;21:384–388; discussion 388-389. doi: 10.1007/pl00012258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowers ED, Robison DJ, Doberneck RC. Pyogenic liver abscess. World J Surg. 1990;14:128–132. doi: 10.1007/BF01670563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong WM, Wong BC, Hui CK, Ng M, Lai KC, Tso WK, Lam SK, Lai CL. Pyogenic liver abscess: retrospective analysis of 80 cases over a 10-year period. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1001–1007. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, Osterman FA Jr, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Zuidema GD. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223:600–607; discussion 607-609. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199605000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rintoul R, O'Riordain MG, Laurenson IF, Crosbie JL, Allan PL, Garden OJ. Changing management of pyogenic liver abscess. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1215–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liew KV, Lau TC, Ho CH, Cheng TK, Ong YS, Chia SC, Tan CC. Pyogenic liver abscess--a tropical centre's experience in management with review of current literature. Singapore Med J. 2000;41:489–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeto RK, Rockey DC. Pyogenic liver abscess. Changes in etiology, management, and outcome. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:99–113. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma MP, Dasarathy S, Verma N, Saksena S, Shukla DK. Prognostic markers in amebic liver abscess: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2584–2588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]