Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate a 36-core saturation biopsy scheme on autopsied prostate glands to estimate the detection rate based on the true cancer prevalence, and to compare the cancer features on biopsy with whole-mount pathological analysis, as saturation biopsies have been proposed as a tool to increase the prostate cancer detection rate, and as a staging tool to identify potentially insignificant cancers before surgery.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We took 36-core needle biopsies in 48 autopsied prostates from men who had no history of prostate cancer. The first 18 cores corresponded to an extended biopsy protocol including six cores each in the mid peripheral zone (PZ), lateral PZ and central zone. Six additional cores were then taken in each of these three locations. We compared the histological characteristics of step-sectioned prostates with the biopsy findings. Tumours were considered clinically insignificant if they were organ-confined with an index tumour volume of <0.5 mL and Gleason score of ≤6.

RESULTS

The pathological evaluation identified 12 (25%) cases of prostate cancer and 22 tumour foci; seven prostate cancers were significant. Of the 22 tumour foci, 16 (73%) were in the PZ. The first 18 cores detected seven cancers (58%), of which five were clinically significant. The last 18 cores detected four cancers, all of which were already detected by the first 18 cores. Of the five cancers remaining undetected by biopsies, two were clinically significant and three were insignificant. Comparison of the histological characteristics between biopsies and step-sectioned prostates showed an overestimation of Gleason score by saturation biopsies in three of seven cases.

CONCLUSIONS

The evaluation of saturation biopsies based on the true prevalence of prostate cancer showed no increase in detection rate over a less extensive 18-core biopsy. Also, saturation biopsies might overestimate the final Gleason score on whole-mount analysis.

Keywords: prostate cancer, saturation biopsies, detection rate, staging

INTRODUCTION

The detection rate of prostate cancer has been enhanced by lowering the PSA threshold level and increasing the number of samples taken at biopsy. As a result, this disease is now detected earlier in its development, as shown by the decreasing pathological stage of prostate cancer in radical prostatectomy (RP) specimens [1,2]. However, small and well-differentiated cancers, designated as ‘clinically insignificant’ [3,4], might not be an immediate threat, and should not be managed with radical and possibly morbid treatment. Biopsy strategies should therefore be designed to detect the most clinically significant cancers while minimizing the detection of clinically insignificant lesions.

The ideal number of biopsies that should be taken to detect all, or at least most, prostate cancers has been controversial and has developed significantly in recent times. TRUS-guided prostate biopsies were first suggested to comprise six cores, three from each side of the prostate. Since the late 1990s, this recommendation was changed to 10–12 cores, based on data that the more extensive biopsies detected 30% more cancers than the conventional sextant biopsy [5]. Prostate saturation biopsies were recently proposed in patients in whom the risk of missing a potential aggressive tumour is high. This is the situation in men with an increasing PSA level despite previous repeated negative prostate biopsies. In these cases, saturation biopsies were reported to have a detection rate of up to 35% [6–9]. Saturation biopsies have also been evaluated as a staging tool to improve the characterization of low-volume and well-differentiated disease in men with a diagnosis of a potential insignificant microfocal cancer on primary biopsy [10]. It was suggested that this technique could identify potential candidates for watchful-waiting strategies on the basis of negative saturation biopsies.

However, studies evaluating prostate cancer detection are influenced by verification bias [11]. Indeed, the reference standard investigation is not used in all patients, as those with a low PSA level do not have a prostate biopsy and those for whom prostate biopsy failed to detect cancer do not undergo surgical verification. Thus, the true sensitivity of biopsy regimens is difficult to estimate. Saturation biopsies are more cumbersome and painful than less extensive biopsy protocols and might require i.v. sedation, regional or general anaesthesia. Therefore, clear evidence for a diagnostic advantage or improvement of staging of the disease is required before saturation biopsies could be recommended in the clinical setting.

We previously reported the results of a detection study on autopsied glands using various biopsy regimens with up to 18 cores [12]. In the present study, we used a saturation biopsy regimen of 36 cores on autopsied glands and compared the biopsy findings with whole-mount analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We prospectively collected 58 consecutive prostate glands from deceased men, provided by the University Hospital and the Onondaga County Medical examiner, Syracuse, NY, and by the National Disease Research Interchange, Philadelphia, PA, USA. The tissue suppliers obtained informed consent from the next of kin. All samples were de-identified to protect the identity of the individual. Age, race and cause of death were recorded. The men had no known history of prostate cancer. At autopsy, the entire prostate gland and seminal vesicles were excised and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Incomplete specimens were received in 10 cases and these samples were excluded from the study, leaving a final sample of 48 prostates available for analysis.

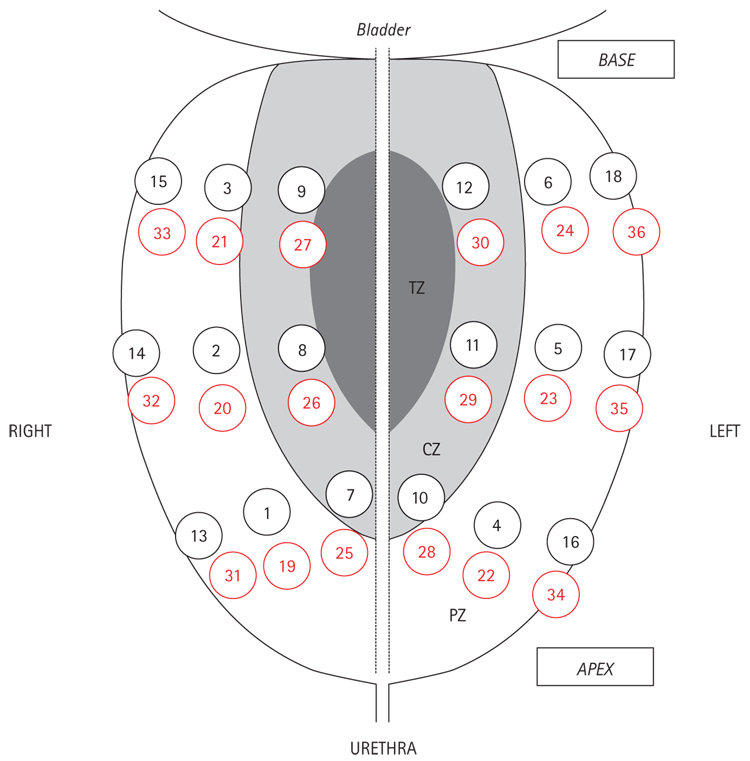

Biopsies were taken in a manner that mimicked a clinical biopsy, by one urologist (N.B.D.), using a standard 18 F spring-loaded biopsy gun (Bard Maxcore, CR Bard, Covington, GA, USA). The biopsy gun needle was inserted through the posterior surface of the gland, and bilateral samples were taken from the apex, mid-gland and base; in all, 36 cores were taken using the same scheme. The first 18 cores corresponded to an extended biopsy protocol including six cores each in the mid peripheral zone (MPZ), the lateral PZ (LPZ) and central zone (CZ) [12]. Six additional cores were taken in each of these three locations, increasing the number of cores to 36 (Fig. 1). Biopsy specimens were individually labelled and placed in formalin for ≥48 h, embedded in paraffin and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. One pathologist (G.dl.R.) microscopically analysed all samples while unaware of the origin. For each biopsy with cancer, the Gleason score, number of positive cores, percentage of cancer involvement in a core, and tumour location were determined.

FIG. 1.

The saturation biopsy scheme: cores 1–18, extended biopsy protocol; cores 1–6, MPZ; cores 7–12, LPZ; cores 13–18, CZ; cores 19–36 (in red) are additional cores; 19–24, MPZ; 25–30, LPZ; 31–36, CZ.

For the whole-mount prostate processing and histological evaluation, after fixation for ≥72 h, the glands were separated from the surrounding tissue. The glands were cut into 4 mm sections perpendicular to the posterior plane. The blocks obtained were labelled and embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned to produce 5-µm whole-mount sections that were stained with haematoxylin-eosin. Each tumour focus detected was outlined on the whole-mount sections. Immunohistochemical studies using a cocktail containing basal cell marker p63 and P504S/α-methylacyl-CoA racemase were performed for cases that were not unequivocally considered cancerous on morphology alone. The total number of tumour foci and their location were recorded. An area of carcinoma was considered a separate focus if it was separated by a low-power field diameter (4.5 mm) from the nearest adjacent focus [13]. Each tumour focus was graded according to the modified Gleason grading system [14].

The surface of each tumour focus was determined by computerized planimetry, using an image-analysis program [15]. Tumour volume was calculated by multiplying each tumour surface by the section thickness (4 mm) and by 1.5 to compensate for tissue shrinkage [16]. The index tumour volume was that of the largest focus of carcinoma. The total tumour volume was calculated as the sum of the volumes of individual foci. Tumours were considered clinically insignificant if they were organ-confined with an index tumour volume of <0.5 mL and Gleason score of ≤6 [3,4].

Mc-Nemar’s test was used to compare the detection rates between 12-, 18-and 36-core biopsies, which accounts for the correlation between proportions. The sensitivity of the biopsy results was calculated. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare tumour volumes between prostate cancers detected and missed by biopsies. In all analyses P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

The 48 prostates were from Caucasian men with a median (range) age of 66 (22–89) years, and the median volume was 35 (13–80) mL. The pathological evaluation identified 12 (25%) prostate cancers and 22 tumour foci (Table 1). The median age of the 12 men with prostate cancer was 75 (44–89) years. The cancers were equally distributed between unifocal and multifocal. Eight cancers were well differentiated (Gleason 6), whereas four were poorly differentiated (Gleason 7). Seven of the 12 prostate cancers were clinically significant by definition (Table 1).

Table 1.

The pathological characteristics of the 12 prostate cancers identified

| Prostate cancers | n , n (%) or median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Pathological stage | |

| pT2a | 6 |

| pT2b | 2 |

| pT2c | 2 |

| pT3a | 2 |

| Gleason score | |

| 6 (3 + 3) | 8 |

| 7 (3 + 4) | 3 |

| 7 (4 + 3) | 1 |

| Number of tumour foci per cancer | |

| 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 1 |

| Index tumour volume, mL | 0.23 (0.02–0.7) |

| Total tumour volume, mL | 0.32 (0.03–1.03) |

| Tumour foci volume (22), mL | 0.1 (0.02–0.7) |

| Clinical significance | |

| Significant | 7 |

| Insignificant | 5 |

| Tumour foci location (22) | |

| PZ | 16 (73) |

| CZ | 6 (27) |

Of the 22 tumour foci, five (23%) were in the MPZ, nine (41%) in the LPZ, two (9%) in both the MPZ and LPZ, and six (27%) in the CZ; seven were in the apex, 13 were in the mid zone and two in the base.

The median (range) biopsy core length was 12 (9–15) mm, and the median saturation biopsy length was 371 (195–421) mm.

Sextant biopsies (first six cores) detected four cancers, of which two were clinically significant. The 12-core biopsies (first 12 cores) detected six cancers, of which four were clinically significant. Extended biopsies (first 18 cores) detected seven cancers, of which five were clinically significant. The difference was not statistically significant. The last 18 cores detected four cancer, but all of these were already detected on some of the first 18-core biopsies. As a result, the detection rate of the saturation biopsy protocol was not increased over an 18-core regimen (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biopsy detection rates among the 12 prostate cancers identified

| Detection rate, n/N |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsies | Overall | Significant cancers | Insignificant cancers |

| Sextant | 4/12 | 2/7 | 2/5 |

| MPZ (cores 1–6) | |||

| Standard biopsies | 6/12 | 4/7 | 2/5 |

| MPZ plus LPZ (cores 1–12) | |||

| Extended | 7/12 | 5/7 | 2/5 |

| MPZ, LPZ and CZ (cores 1–18) | |||

| Saturation (cores 1–36) | 7/12 | 5/7 | 2/5 |

Table 3 compares the Gleason score determined on biopsies with that determined on whole-mount analysis. Of the four cancers detected by sextant biopsies, the Gleason score was underestimated by biopsies in two. Of the six cancers detected by the 12-core biopsies, the Gleason score was underestimated in three. Of the seven cancers detected by the 18-core biopsies, the Gleason score was underestimated in one and overestimated in one. Of the same seven cancers detected by the saturation biopsies, the Gleason score was not underestimated in any case, but overestimated in three.

Table 3.

Correlation between Gleason score on biopsies and whole-mount analysis

| Cores |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–6 | 7–12 | 13–18 | 19–36 | Whole-mount analysis | |||

| CND | CND | CND | CND | 3 + 3 | |||

| CND | CND | 3 + 3 | 3 + 4 | 3 + 3 | |||

| CND | CND | CND | CND | 3 + 4 | |||

| CND | 3 + 3 | CND | CND | 3 + 3 | |||

| CND | CND | CND | CND | 3 + 3 | |||

| 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 | CND | CND | 3 + 4 | |||

| 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 | CND | 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 | |||

| CND | CND | CND | CND | 3 + 3 | |||

| 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 | 3 + 4 | 3 + 4 | 3 + 3 | |||

| CND | 3 + 3 | CND | 4 + 3 | 3 + 4 | |||

| 3 + 4 | 3 + 4 | 3 + 4 | CND | 4 + 3 | |||

| CND | CND | CND | CND | 3 + 3 | |||

CND, cancer not detected.

Five cancers remained undetected by biopsies, of which three were unifocal and in the MPZ, LPZ and CZ. The other two undetected cancers were bifocal; they were in the LPZ in the first, and in the MPZ and CZ in the second. Two cancers were clinically significant and three were insignificant; however, all had an index tumour volume of <0.5 mL. The median index and total tumour volume of cancers undetected by biopsies were 0.08 and 0.09 mL, respectively. By comparison, that of cancers detected by biopsies were 0.5 and 0.6 mL, respectively (P <0.05, Mann–Whitney test).

DISCUSSION

The trend has been to take increasingly many prostate biopsies to detect more cancers. Sextant biopsies have been all but abandoned, and most studies recommend extended biopsy protocols of 12 cores [5,12]. In a previous study, we took 18 biopsies in autopsied glands from deceased men with no history of prostate cancer. These 18 biopsy cores were targeting the same prostatic areas as the first 18 cores taken in the present study; six each were taken in the MPZ, LPZ and CZ. The 18 cores together detected 25/47 (53%) cancers, but the detection rate of the 12 biopsy cores targeting the MPZ and LPZ was the same as that of the 18 biopsy cores together, and significantly higher than that of the traditional sextant biopsies (six cores targeting the MPZ) (53% vs 30%, P =0.003). Others also suggested that biopsies directed to the CZ had a low likelihood of identifying cancer in the absence of positive biopsies from the PZ [5,17]. We also reported that the six additional biopsies from the LPZ increased both the detection rate of ‘clinically significant and insignificant’ cancer, as defined by Stamey et al. [3] and Epstein et al. [4]. According to these authors, organ-confined cancers with an index tumour volume of <0.5 mL and a Gleason score of <7 are more likely to remain latent, which makes them ‘clinically insignificant’ [3,4]. Although this definition is purely histological and does not account for other important variables such as age and comorbidities, it is likely to characterize the potentially aggressive tumours, and thus to target patients needing thorough screening and treatment.

In the present study, we doubled the number of biopsy cores taken in each area of the prostate to assess the value of saturation biopsies as a detection and staging tool. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating saturation biopsies in autopsied glands. This type of material prevented the results from being influenced by verification bias. In clinical studies, the reference standard investigation is not used in all patients, as those with a low PSA level do not have a prostate biopsy, and those for whom prostate biopsy failed to detect cancer do not undergo surgical verification. Unlike clinical studies, which fail to identify cancers present but missed by the biopsies, most cancers present in autopsied prostates can be identified and characterized. In the present study, the overall prevalence of prostate cancer was 25%, which is comparable to our latest detection study on autopsied material (29%) but lower than the 36% we found in Wayne County, Michigan a decade ago [18,19]. Some of these discrepancies could be explained by demographic differences. Also, we included in our study only men with no history of prostate cancer. However, most of the cancers identified were considered clinically significant (seven of 12) according to their volume, Gleason score and pathological stage.

The saturation biopsies detected no additional cancers as compared with an extended biopsy protocol comprising six cores from each of the MPZ, LPZ and CZ. As a result, the detection rate of both biopsy protocols was similar. These findings were consistent with those of previous clinical studies evaluating saturation biopsies as an initial biopsy strategy. Jones et al. [20] evaluated a 24-core saturation biopsy protocol as an initial biopsy in 139 patients with a PSA level of ≥2.5 ng/mL, and compared their results with those from 87 patients who had had a 10-core initial biopsy. The difference between detection rates was not statistically different (44.6% for saturation biopsies vs 51.7% for 10-core biopsies, P >0.9). Moreover, analysis by PSA level failed to show a benefit for the saturation technique for any degree of PSA increase [20]. In another study, Descazeaud et al. [21] reported that the detection rate of their 21-core biopsy strategy was similar to that of their 10–12-core biopsy scheme as an initial biopsy strategy [21]. However, these studies, because of the absence of systematic surgical verification, could not give information on the real percentage of cancers missed by saturation biopsies. We found that five of the 12 cancers identified at whole-mount analysis remained undetected by saturation biopsies, two of which were clinically significant. These undetected cancers were mostly in the MPZ and LPZ, although one was unifocal and in the CZ. However, they were missed even by doubling the number of biopsies in each of these locations. These results, based on the true prevalence of prostate cancer, might suggest that ≈40% of cancers would stay undetected whatever the number or location of biopsies taken, and that some of these undetected cancers might be ‘clinically significant’.

We also evaluated saturation biopsies as a staging tool, to enhance the characterization of prostate cancer at biopsy. Quantification and qualification of prostate cancer with saturation biopsies was investigated previously. Boccon-Gibod et al. [10] evaluated the ability of a 32-core saturation biopsy protocol to improve the characterization of prostate cancer in 35 consecutive patients with the diagnosis of potentially insignificant cancer based on favourable features on standard biopsy. Saturation biopsies were negative for cancer in a third of the cases, suggesting that tumour detected at the primary biopsy was probably of low volume. Of the 23 patients with positive saturation biopsies, 17 showed cancer at multiple sites and seven were upgraded to a Gleason score of ≥7. These patients were considered to have significant cancer and were offered active treatment. Among the nine patients who had RP, only one had insignificant cancer on whole-mount analysis. The present results showed that saturation biopsies missed two of the seven significant cancers characterized on whole-mount analysis. These cancers were probably missed because of their low volume. However, one of them had extracapsular extension and the other had a Gleason score of 7 (3 + 4). We also found that while standard biopsies underestimated the Gleason score in half the cases, saturation biopsies overestimated the Gleason score in three of seven cases. This tendency of saturation biopsy to overestimate pathological features was previously reported by others. Epstein et al. [22] took saturation biopsies ex vivo in 103 RP specimens from patients who were likely to have insignificant prostate cancer, based on favourable pathological features on standard biopsy. On whole-mount analysis, 71% of the cancers were ‘clinically insignificant’ according to the previously mentioned histological criteria, meaning that 29% had been therefore misclassified using the standard biopsy scheme. Saturation biopsy (with a mean number of 44 cores) detected 81/103 cancers, and predicted clinically insignificant cancer if the Gleason score was <7 with three or fewer positive cores, or if the maximum length of cancer in one core was <4.5 mm and the total for all cores was <5.5 mm. These criteria for predicting clinically insignificant cancer had a sensitivity of 71.9% and specificity of 95.8%. However, with these criteria, their saturation biopsy protocol overestimated tumour volume and Gleason score in 11.5% (false-positive rate). An alternative considering half as many cores (mean 22) was assessed, and this alternative scheme predicted insignificant cancer if the Gleason score was <7 and the total cancer length was <2.75 mm, or if the total length of cancer was <9.5 mm with three or fewer positive cores. This approach yielded the same sensitivity but an increased specificity of 97.1%, suggesting that a less extensive saturation biopsy scheme would be likely to decrease the overestimation of Gleason score and tumour volume.

The present study has several limitations, the most obvious being that we only assessed 48 prostates for saturation biopsies and only 12 (25%) had cancer in this population. However, once the interim analysis showed that saturation biopsies yielded no additional cancers not already detected by the 18-core protocol, we discontinued the investigation. Second, the definition of ‘clinical significance’ as adopted from Stamey et al. [3] and Epstein et al. [4] does not include age and comorbidities. All the cancers detected in this study would have been ‘clinically insignificant’ as none of the men were known to have prostate cancer. However, the aim of this autopsy study was not to select the best candidates for prostate cancer screening or active treatment, but only to evaluate the results of saturation biopsies based on the true prevalence of prostate cancer and histological criteria.

In conclusion, evaluating saturation biopsies based on the true prevalence of prostate cancer showed no increase in detection rate beyond a less extensive 18-core biopsy. In addition, saturation biopsies might overestimate the final Gleason score on whole-mount analysis.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- (M)(L)PZ

(mid) (lateral) peripheral zone

- CZ

central zone

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Master VA, Chi T, Simko JP, Weinberg V, Carroll PR. The independent impact of extended pattern biopsy on prostate cancer stage migration. J Urol. 2005;174:1789–1793. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000177465.11299.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galper SL, Chen MH, Catalona WJ, Roehl KA, Richie JP, D’Amico AV. Evidence to support a continued stage migration and decrease in prostate cancer specific mortality. J Urol. 2006;175:907–912. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamey TA, Freiha FS, McNeal JE, Redwine EA, Whittemore AS, Schmid HP. Localized prostate cancer. Relationship of tumor volume to clinical significance for treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:933–938. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<933::aid-cncr2820711408>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, Brendler CB. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994;271:368–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eichler K, Hempel S, Wilby J, Myers L, Bachmann LM, Kleijnen J. Diagnostic value of systematic biopsy methods in the investigation of prostate cancer: a systematic review. J Urol. 2006;175:1605–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabets JC, Jones JS, Patel A, Zippe CD. Prostate cancer detection with office based saturation biopsy in a repeat biopsy population. J Urol. 2004;172:94–97. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132134.10470.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart CS, Leibovich BC, Weaver AL, Lieber MM. Prostate cancer diagnosis using saturation biopsy technique after previous negative sextant biopsies. J Urol. 2001;166:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleshner N, Klotz L. Role of ‘saturation biopsy’ in the detection of prostate cancer among difficult diagnostic cases. Urology. 2002;60:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borboroglu PG, Stewart WC, Riffenburgh RH, Amling CL. Extensive repeat transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy in patients with previous benign sextant biopsies. J Urol. 2000;163:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boccon-Gibod LM, Delongchamps NB, Toublanc M, Boccon-Gibod LA, Ravery V. Prostate saturation biopsy in the reevaluation of microfocal prostate cancer. J Urol. 2006;176:961–963. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Punglia RS, D’Amico AV, Catalona WJ, Roehl KA, Kuntz KM. Effect of verification bias on screening for prostate cancer by measurement of prostate-specific antigen. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:335–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas GP, Delongchamps NB, Jones R, et al. Needle biopsies on autopsy prostates: sensitivity of cancer detection based on true prevalence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1484–1489. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troncoso P, Babaian RJ, Ro JY, Grignon DJ, von Eschenbach AC, Ayala AG. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive prostatic adenocarcinoma in cystoprostatectomy specimens. Urology. 1989;34:52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Concensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228–1242. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noguchi M, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Yemoto CE. Assessment of morphometric measurements of prostate carcinoma volume. Cancer. 2000;89:1056–1064. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1056::aid-cncr15>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schned AR, Wheeler KJ, Hodorowski CA, et al. Tissue-shrinkage correction factor in the calculation of prostate cancer Volume. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1501–1506. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199612000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel AR, Jones JS, Rabets J, DeOreo G, Zippe CD. Parasagittal biopsies add minimal information in repeat saturation prostate biopsy. Urology. 2004;63:87–89. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakr WA, Haas GP, Cassin BF, Pontes JE, Crissman JD. The frequency of carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the prostate in young male patients. J Urol. 1993;150:379–385. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakr WA, Grignon DJ, Crissman JD, et al. High grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) and prostatic adenocarcinoma between the ages of 20–69: an autopsy study of 249 cases. In Vivo. 1994;8:439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones JS, Patel A, Schoenfield L, Rabets JC, Zippe CD, Magi-Galluzzi C. Saturation technique does not improve cancer detection as an initial prostate biopsy strategy. J Urol. 2006;175:485–488. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Descazeaud A, Rubin M, Chemama S, et al. Saturation biopsy protocol enhances prediction of pT3 and surgical margin status on prostatectomy specimen. World J Urol. 2006;24:676–680. doi: 10.1007/s00345-006-0134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein JI, Sanderson H, Carter HB, Scharfstein DO. Utility of saturation biopsy to predict insignificant cancer at radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2005;66:356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]