Abstract

Eukaryotic lanthionine synthetase C-like protein 1 (LanCL1) is homologous to prokaryotic lanthionine cyclases, yet its biochemical functions remain elusive. We report the crystal structures of human LanCL1, both free of and complexed with glutathione, revealing glutathione binding to a zinc ion at the putative active site formed by conserved GxxG motifs. We also demonstrate by in vitro affinity analysis that LanCL1 binds specifically to the SH3 domain of a signaling protein, Eps8. Importantly, expression of LanCL1 mutants defective in Eps8 interaction inhibits nerve growth factor (NGF)-induced neurite outgrowth, providing evidence for the biological significance of this novel interaction in cellular signaling and differentiation.

Keywords: LanCL1, lanthionine synthetase, glutathione, Eps8, SH3, NGF

Lanthionine synthetase C-like protein 1 (LanCL1) is a mammalian homolog of prokaryotic lanthionine synthetases (LanCs). LanC enzymes catalyze regiospecific, intramolecular Michael addition reactions between cysteine and dehydrated serine or threonine residues of particular precursor polypeptides, yielding potent antibiotics or “lantibiotics” (Chatterjee et al. 2005). Human LanCL1 is a 399-residue peripheral membrane protein originally discovered in a search for binding partners to the erythrocyte protein stomatin, a factor in the disease hereditary overhydrated stomatocytosis (Bauer et al. 2000; Mayer et al. 2001). It was independently identified as a binding partner of Plasmodium PfSBP1 during malarial infection (Blisnick et al. 2005) and as a novel binding partner for the redox regulatory, sulfurous tripeptide glutathione (GSH) (Chung et al. 2007). LanCL1 mRNA and protein are most abundantly expressed in the brain (Bauer et al. 2000), and LanCL1 is up-regulated in the spinal cord tissue of the SOD1G93A mouse, a favored model for the motor neuron disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Chung et al. 2007). In contrast, its homolog, LanCL2, is more ubiquitously expressed with an N-terminal myristoylation domain that associates with phosphoinositol phosphates (Landlinger et al. 2006). Currently, very little is known about the structure or function of eukaryotic LanCL1/2 at the molecular and cellular levels.

Here, we report the first crystal structures of a eukaryotic LanCL protein, human LanCL1, in both free form and complexed with GSH. This is the first cocrystal structure of a lantibiotic cyclase (or homolog) bound to a ligand. Like LanC/NisC (Li et al. 2006), LanCL1 exhibits a double seven-helix barrel fold plus multiple GxxG sequence motifs, which constitute the structural basis for the Zn2+-dependent binding of GSH. In addition, we identified a novel binding mode between LanCL proteins and the SH3 domain of Eps8, a known receptor kinase substrate that mediates signal transduction processes (Scita et al. 1999). Indeed, the LanCL–Eps8 interaction involves a three-dimensional (3D) structural framework, as opposed to a linear proline-rich sequence motif. Furthermore, LanCL1 mutants defective in Eps8 interaction inhibit NGF (nerve growth factor) signaling-mediated neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells, lending support to the biological significance of the LanCL1–Eps8 interaction in NGF signal transduction and neuron differentiation.

Results and Discussion

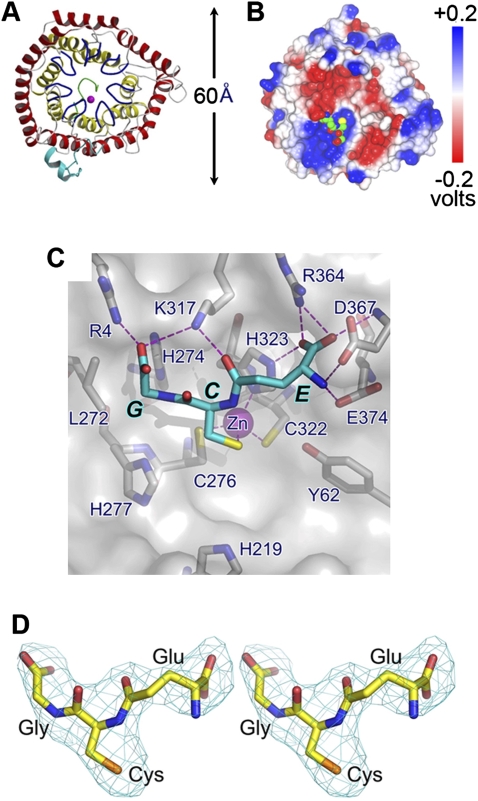

The crystal structure of LanCL1 consists of two layers of α-helical barrels formed by 14 α-helices (α1–α14), with the inner and outer barrel each containing seven helices (Fig. 1). The outer barrel is formed by the odd-numbered helices that are parallel to one another, while the inner barrel is formed by the even numbered helices that are also parallel to one another. The orientation of outer barrel helices is opposite to that of inner barrel helices, but both inner and outer barrels have a left-handed twist, with the helical axis offset by ∼30° from the axis of the residing barrel. The C-terminal end of the inner barrel has a wider opening but is blocked by a short helix, η1, formed by C-terminal residues. At the N terminus, there are two short helices (η0 and α0) attached to the surface of the core domain. The overall folded structure of LanCL1 resembles that of its bacterial homolog LanC/NisC, with a root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 1.8 Å for 245 Cα atom pairs.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of LanCL1. (A) Ribbon representation of human LanCL1. The outer helix barrel is depicted in red and the inner helix barrel is shown in yellow. The seven GxxG-containing bulges are colored blue. N-terminal and C-terminal regions are colored cyan and green, respectively. The Zn2+ ion is depicted with a magenta sphere. (B) Electrostatic potential distribution of LanCL1. Electrostatic potential is mapped on the molecular surface. Bound GSH is shown in a space-filling model, with carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms colored in green, blue, red, and yellow respectively. The orientation of the molecule is similar to that seen in A. (C) Crystal structure. GSH is shown by a cyan stick model, and LanCL1 is shown in a molecular surface model superimposed with selected residues depicted by gray stick models. Zn2+ ion is shown as a magenta sphere. Oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur atoms are colored red, blue, and yellow, respectively. Hydrogen bonds (or salt bridges) are shown as dashed magenta lines. Amino acid residues surrounding and those of GSH are labeled as single letters. (D) Stereo view of the electron density of the bound GSH molecule. The 2.8 Å Fo–Fc electron density map was phased with the final refined model, omitting GSH followed by a few cycles of refinement to reduce bias. It is contoured at three standard deviations and overlapped with the stick model of GSH.

Amino acid sequence alignment indicates that the N-terminal end of the inner barrel is the most conserved region among LanCL family members (Supplemental Fig. S1). The N terminus of each of the seven inner barrel helices starts with a bulged seven-residue turn (residues numbered as −6 to 0). This bulged turn has a glycine residue (Gly0) at its C-terminal end; i.e., the first amino acid residue of the following α-helix. This Gly residue is required for the bulged turn to adopt a Gly-specific backbone conformation by forming a hydrogen bond between the main chain atoms of residues 0 and −4. An exception to this rule is Gly278 in the fifth GxxG motif, and this anomaly appears to be compensated for by its following Gly residue to provide the required backbone flexibility. In each of the seven inner barrel helices, the +3 position consists of a Gly residue, which accommodates the backbone of the bulged turn at the −3 position. Gly residues at positions 0 and +3 in each bulge are highly conserved among LanCL family members and are often referred as a GxxG motif (Li et al. 2006). The main chain carbonyl oxygen atom of residue −2 frequently forms hydrogen bonds with the main chain amide groups of residues −2 and/or −3 in the neighboring bulge. Position +4 inside the helix is often occupied by a β-branched residue. These seven conserved GxxG-containing bulges located at the N termini of the inner helices appear to be a signature feature of the LanCL family of proteins, since they are absent in other double helix barrel proteins such as the farnesyl transferase (Park et al. 1997). Potential active site residues are located on these loops. In addition, these bulged loops reduce the entry size of the central cavity formed by the inner helix barrel by about one-third relative to other known double helix barrel proteins. Thus, LanCL1 is unlikely to use the central cavity as a substrate-binding site as proposed for the farnesyl transferase.

LanCL1 is known to bind zinc ions (Chatterjee et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006). In our crystal structure, each LanCL1 moiety contains one Zn2+ ion, which is anchored in a tetrahedral coordination. Three of the four Zn2+-binding ligands are provided by the Sγ group of Cys276 in the fifth GxxG motif, Sγ of Cys322 in the sixth GxxG motif, and Nδ1 of His323, also in the sixth GxxG motif. The corresponding residues in LanC/NisC also participate in Zn2+ binding and are conserved in the LanCL family.

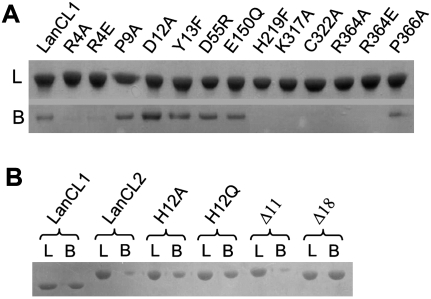

LanCL1 from bovine brain was shown recently to bind GSH (Chung et al. 2007). Our results showed that the recombinant human protein can also bind specifically to GSH that was covalently linked to Sepharose 4B beads through the sulfhydryl group on its cysteine residue, and that the bound protein can be eluted by 1 mM GSH (Fig. 2A). Similarly, recombinant human LanCL2 can also bind specifically to the GSH–Sepharose resin under the same condition, albeit with much lower affinity (Fig. 2B). Therefore, both LanCL1 and LanCL2 bind GSH with or without its free sulfhydryl group.

Figure 2.

Binding of LanCL1/2 variants with GSH. (A) LanCL1–GSH binding. An excessive amount (5 mg) of the protein sample was loaded onto a GSH–Sepharose4B column (0.5 mL bed volume), washed with 30 mL of PBS buffer, and optionally eluted by 1 mM GSH in 10 μM ZnCl2, 200 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Lanes labeled with L (loaded) denote preincubated protein samples (∼4 μg), and those labeled with B (bound) indicate LanCL1 protein that bound to the GSH-Sepharose (from 7.5 μL of the resin slurry). Samples were analyzed by (12%) SDS-PAGE. The assay shown in the figure is representative of repeated experiments. (B) LanCL2–GSH binding and effects of the N terminus. Sample treatment was similar to A. LanCL1 was used as a positive control, followed by LanCL2 (full-length without an N-terminal tag) and its variants of point mutations and N-terminal truncations.

To determine the structural basis of the LanCL1–GSH interaction, we cocrystallized LanCL1 with GSH under conditions similar to that of the GSH-free crystal. While the packing was similar to that of the GSH-free crystal, the space group of the LanCL1–GSH complex crystal changed from P3221 to P6522 in addition to a c axis expansion by >30 Å. The overall crystal structure of the LanCL1 monomer remains similar, regardless of whether it is bound to GSH. More importantly, in the cocrystal structure we observed a GSH molecule for each LanCL1 molecule in the initial, molecular replacement phased, electron density map. The average B-factor of the GSH molecules in the final refined model is 78 Å2, comparable with that of the LanCL1 molecules. The GSH-binding mode of LanCL1 differs significantly from other known GSH-binding proteins such as the GST protein (Ji et al. 1992), the GSH synthetase (Yamaguchi et al. 1993), and the glyoxalase (Cameron et al. 1997). In addition to the Zn2+-mediated binding, there are extensive interactions between LanCL1 and GSH (Fig. 1B,C). Most of the GSH-binding residues (<3.6 Å) are conserved in vertebrate but not in bacterial LanC proteins (Supplemental Fig. S1). Compared with the GSH-free LanCL1 structure, the LanCL1–GSH complex structure indicates that LanCL1 has a preformed GSH-binding site that can assume extensive interactions with GSH in addition to the Zn2+ coordination.

To verify the interaction between LanCL1 and GSH observed in the cocrystal, we introduced point mutations into LanCL1 and tested the ability of the mutants to bind GSH in vitro. Recombinant mutant proteins expressed in Escherichia coli were purified and incubated with GSH–Sepharose beads (Fig. 2A). As predicted from the LanCL1–GSH complex structure, mutations R4A/E (Arg4 to Ala or Glu), K317A, C322A, and R364A/E all abolished the ability of LanCL1 to bind GSH. Among these mutations, C322A is predicted to disrupt Zn2+ coordination, while the others are likely to disrupt the direct interaction between LanCL1 and GSH (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, P9A, D12A, Y13F, D55R, E150Q, and P366A mutations did not alter the ability of LanCL1 to bind immobilized GSH, consistent with the corresponding structural predictions. An apparent oddity of H219F, which was not in direct contact with GSH yet showed reduced binding with GSH beads, may be explained by a stereo collision with the linker attaching GSH to the bead. Taken together, the in vitro binding data corroborated the structure-based prediction, suggesting that LanCL1 may interact with GSH in the same fashion in solution and that an intact Zn2+-binding site on LanCL1 is required for GSH binding.

Sequence alignment between LanCL1 and LanCL2 indicated an extra N-terminal peptide in LanCL2 (Supplemental Fig. S1), which may function as a switch to regulate the binding of LanCL2 to potential ligands or substrates such as GSH. To test this hypothesis, we constructed two LanCL2 deletion mutants lacking the first 11 (Δ11) or 18 (Δ18) N-terminal residues, respectively, and two point mutants converting His12 to either Ala (H12A) or Glu (H12Q). While LanCL2Δ11 showed no effect on GSH binding, LanCL2Δ18, H12A, and H12Q mutants all showed increased binding to the GSH beads compared with the wild-type LanCL2 (Fig. 2B). Because His12 is the only histidine residue in the N-terminal peptide, the increased GSH binding by mutations at His12 suggests that this residue plays an important role in the regulatory function of the N-terminal peptide. It is likely that the His12 residue serves as the fourth Zn2+ ligand, thus blocking GSH binding, in a “closed” form of LanCL2.

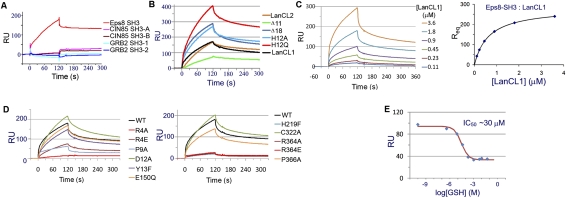

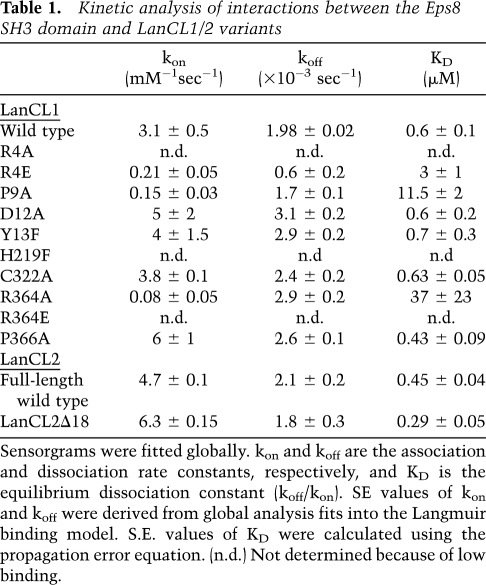

In addition to domains for Zn2+ coordination and GSH binding, LanCL1 contains two PxxDY sequences (residues 9–13 and 252–256) and two PxxP motifs (residues 145–148 and 366–369), both of which are potential SH3-binding sites (Mongiovi et al. 1999) and were found to be conserved in LanCL2 (Supplemental Fig. S1). We tested these sites for their ability to bind SH3 domains from Eps8, GRB2, and CIN85, which are known to function in various signaling pathways. We expressed and purified the SH3 domain of mouse Eps8 (SH3Eps8, 92% identical in sequence with the human one), the SH3-1 and SH3-2 domains of human GRB2, and the SH3-A and SH3-B domains of human CIN85. In vitro surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding assays indicated that only SH3Eps8, but not other proteins, was able to bind LanCL1 (Fig. 3A). Similar SPR results were obtained in an opposite assay format, in which the LanCL proteins were immobilized. We determined the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) between human LanCL1 and the mouse SH3Eps8 domain to be 0.6 μM (Table 1). Similarly, the KD values for LanCL2 and LanCL2Δ18 were 0.45 μM and 0.29 μM, respectively. In contrast, the KD values between LanCL1/2 and other SH3 domains were all >200 μM. Furthermore, the interaction between SH3Eps8 and LanCL1/2 was diminished by GSH in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3E), suggesting a regulatory mechanism. In addition, this SPR assay allowed us to estimate the dissociation constant (KD = 0.7 mM) between LanCL1 and GSH (Supplemental Fig. S2). Taken together, our data demonstrate a specific interaction between the LanCL proteins and the SH3 domain of Eps8, and this interaction is negatively regulated by GSH.

Figure 3.

LanCL1 interaction with Eps8 SH3 as determined by SPR. (A) Interaction between a number of SH3 domains and immobilized LanCL1. Only the Eps8 SH3 domain showed significant binding. (B) Interaction between LanCL2 variants and immobilized Eps8 SH3. Wild-type (WT) LanCL1 was included as a reference. Disrupting the N terminus of LanCL2 appears to improve its binding with the Eps8 SH3 domain. Binding was performed using 1.0 μM analyte and repeated multiple times. Representative sensorgram curves are shown. (C) Eps8 SH3 interaction with wild-type LanCL1. GST-Eps8 SH3 fusion protein was immobilized on the sensor chip (∼2000 response units [RU]). LanCL1 was introduced at concentrations ranging from 0.11 to 3.6 μM. Representative sensorgram curves are shown in the left panel. Equilibrium SPR signal (Req) calculated at each concentration is plotted on right. (D) Comparison of LanCL1 variants binding to immobilized GST-Eps8 SH3. Mutations in the N-terminal and C-terminal halves are divided into two panels for clarity. Wild-type LanCL1 binding is shown in both panels by a black line. Binding was performed using 1.8 μM analyte. (E) Inhibitory effects of GSH on LanCL1–SH3 binding. LanCL1 (5 μM) was bound to immobilized Eps8 SH3 domain in the presence of GSH of various concentrations (0–50 mM). RU signals of the LanCL1–SH3 binding at the beginning of the dissociation period were recorded (diamonds), and the red line is the fitting curve to a competitive inhibition model.

Table 1.

Kinetic analysis of interactions between the Eps8 SH3 domain and LanCL1/2 variants

We next carried out mutagenesis studies to determine the binding mode between LanCL1 and SH3Eps8. As mentioned earlier, LanCL1 contains two PxxDY sequence motifs. The C-terminal P246xxDY250 motif located on helix α9 is mostly solvent-inaccessible and therefore is unlikely to be a ligand for the SH3 domain. The P9xxDY13 motif, located in the N-terminal peptide on the surface of the 3D structure, has an extended conformation and is flanked by two short helices, η0 and α0. Although a previous study reported that binding of a PxxDY motif to the SH3Eps8 domain is strictly dependent on the Asp–Tyr residues as well as the proline residue (Mongiovi et al. 1999), our mutation analysis showed that D12A and Y13F variants of LanCL1 exhibited essentially the same binding affinity for SH3Eps8 as the wild-type protein (Fig. 3C; Table 1), suggesting that the P9xxDY13 motif is not a major SH3-binding site in LanCL1.

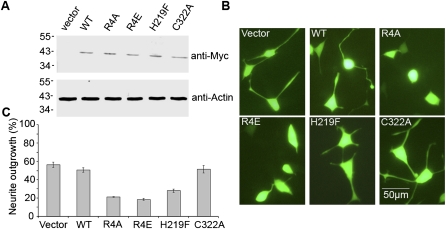

To understand the biological significance of the LanCL1–Eps8 interaction, we investigated its possible role in NGF signaling and neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. PC12 cells contain both EGF and NGF receptors, but EGF signaling promotes cell proliferation while NGF signaling promotes cell differentiation into a sympathetic neuron-like phenotype with long neurites. We previously employed this system to reveal an important role of Rab5-regulated endocytic trafficking in NGF signaling and neurite outgrowth (Liu et al. 2007). Wild-type and mutant LanCL1 proteins were expressed in PC12 cells with a bidirectional expression vector, pBI/eGFP, which simultaneously expressed an enhanced version of GFP for identification of transfected cells. The cells were treated with NGF, followed by identification of differentiated cells containing long neurites among the transfected, GFP-expressing cells by fluorescence microscopy. In control cells transfected with the pBI/eGFP empty vector, nearly 60% of cells differentiated to grow neurites (Fig. 4). Overexpression of wild-type LanCL1 did not significantly affect the neurite outgrowth. In contrast, overexpression of the LanCL1 mutants defective in Eps8 interaction, including R4A, R4E, and H219F, strongly inhibited NGF-induced neurite outgrowth by >50% (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the C322A mutant defective in GSH interaction but normal in Eps8 binding had little effect on neurite outgrowth. Furthermore, the P9A, D12A, and Y13F mutants, which bind Eps8 normally in vitro (Fig. 3D), showed no effect on neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells transfected with LanCL1 mutants in response to NGF treatment. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the overexpression of myc-tagged LanCL1 proteins in PC12 cells. (Top) Expression levels of the transfected LanCL1 constructs as probed by the anti-myc antibody. (Bottom) Actin level in each sample as the loading control was detected by anti-actin antibody. The vector lanes contain samples from cells transfected with the empty pBI/eGFP vector. (B) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of the cells after a 4-d treatment with 50 ng/mL NGF. Cells ware transfected either with the empty pBI/eGFP vector or with constructs expressing the indicated LanCL1 variants. Bar, 50 μm. (C) Quantification of PC12 cell differentiation. Upon expression of the indicated LanCL1 variants, the percentage of differentiated cells with extended neurites was determined among the transfected cells expressing eGFP. In each case, 500 transfected cells were measured, and error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments.

We identified a direct and specific interaction between LanCL1/2 and the Eps8 SH3 domain, through a screen of five SH3 domains from three adaptor proteins involved in EGF and other signal transduction pathways. Interestingly, the LanCL1–SH3Eps8 interaction can be significantly inhibited by ∼1 mM GSH, which overlaps with the cellular concentration of GSH (Jacob et al. 2004). This type of negative regulation of protein–protein interactions by the free, reduced form of GSH would be potentially useful in vivo, in addition to glutathionylation, as a mechanism to regulate protein functions in response to cellular redox status. Further mutagenesis and affinity analyses suggest that the Eps8 SH3 domain may employ a novel binding mode to interact with LanCL1. SH3 domains are well known protein-binding domains, usually targeting proline-rich peptide regions. While the SH3 domain of Eps8 has been shown to bind a PxxDY motif (Mongiovi et al. 1999; Aitio et al. 2008), our mutagenesis data do not support such a binding mode between Eps8 and either of the two PxxDY motifs in LanCL1. Moreover, neither PxxDY motif is located close to the GSH-binding site or shows conformational changes in the crystal structure upon GSH binding, and point mutations of the key residues Asp and Tyr have little effect on SH3 binding. Therefore, it would be difficult to reconcile a PxxDY-binding model with the observation that GSH inhibits LanCL1–SH3 binding. We therefore favor models for binding between LanCL1 and SH3 that would require a more extensive molecular surface interaction from both of these molecules.

Eps8 is a widely expressed, multidomain signaling protein that coordinates at least two disparate GTPase-dependent mechanisms: EGF-stimulated actin reorganization via the Rac pathway and/or inhibition of receptor internalization via inactivation of the Rab5 pathway (Mongiovi et al. 1999). Our findings extend the Eps8 functions and provide evidence for a novel LanCL1–Eps8 interaction in another receptor kinase-mediated signal transduction pathway, the NGF receptor (TrkA)-mediated neurite outgrowth and cell differentiation. Our data are consistent with the observation that Eps8 is involved in dendrite and synapse formation (Proepper et al. 2007) coincident with the high expression of LanCL1 in the central neural system (Offenhauser et al. 2006). Indeed, all LanCL1 mutants defective in Eps8 binding strongly inhibit NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells, while wild-type and other LanCL1 mutants that remain able to bind Eps8 have no such inhibitory effect (Fig. 4). LanCL1 normally targets to the plasma membrane, which may be a necessary step for LanCL1 to interact with Eps8 in the cell. In this regard, the LanCL1 mutants could compete with endogenous LanCL1 for the binding sites on the plasma membrane, thereby preventing the latter from binding to the membrane and its subsequent interaction with Eps8. The LanCL1–Eps8 interaction may directly contribute to neurite outgrowth, but the mechanism requires further investigation. In addition, LanCL1 may compete with E3b1 and RN-tre for interactions with Eps8, which all involve the Eps8 SH3 domain. The resulting inhibition of the latter pathways, which promote cell proliferation during EGF signal transduction, could also contribute to the neurite outgrowth and cell differentiation. Therefore, our data suggest that the LanCL1–Eps8 interaction is involved in NGF signaling, and the LanCL1 mutants defective in Eps8 interaction may abrogate the endogenous LanCL1–Eps8 interaction, leading to inhibition of NGF signaling and neurite outgrowth.

The KD between LanCL1 and Eps8 SH3 is in the submicromolar range, which is comparable with the KD between the same SH3 domain and other physiological ligands (Mongiovi et al. 1999). The cellular concentration of Eps8 is ∼0.8 μM (Disanza et al. 2004). Taken together with the results in PC12 cells (Fig. 4) and the high expression of LanCL1 in some tissues (Mayer et al. 1998), our data suggest that the Eps8 and LanCL1 interaction is biologically relevant. Further studies using transgenic animals should help determine phenotypes arising from either ablation or overexpression of LanCL proteins, and clarify the biological functions of LanCL proteins.

Materials and methods

Protein crystallization and structural determination

Recombinant full-length human LanCL1 (residues 1–399) was expressed and purified from E. coli as a fusion protein with an N-terminal His16 tag. The recombinant protein was first crystallized in the absence of exogenous GSH using a precipitant solution containing 1.5 M ammonium formate and 0.1 M bicine (pH 9.0). Cocrystallization of LanCL1 with 20 mM GSH was performed under a similar condition. Phases of the GSH-free LanCL1 crystal structure were solved by using the zinc-based SAD method. Phases of the crystal structure of the GSH–LanCL1 complex were determined by the MR method. PDB IDs of the final coordinates are 3E6U and 3E73.

All LanCL1, LanCL2 variants were expressed in E. coli as His tag fusion proteins. Human CIN85 SH3-A and SH3-B domains, GRB2 SH3-1 and SH3-2 domains, and the mouse Eps8 SH3 domain were expressed in E. coli as N-terminal GST fusion proteins and were purified with affinity chromatography.

Neurite outgrowth assay

The assay was previously described (Liu et al. 2007). Briefly, Tet-Off PC12 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per dish, grown to 70%–80% confluency at 37°C, and transfected with various pBI/eGFP constructs. Cells were allowed to recover in growth medium and to express the recombinant proteins for 24 h. The growth medium was then replaced with a medium containing NGF (50 ng/mL) and incubated for 4 d at 37°C. Neurite outgrowth was analyzed with an inverted fluorescence microscope. Differentiated cells were defined as those containing at least one neurite twice as long as the cell body diameter.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P.P. Di Fiore for kindly providing the expression plasmid for the SH3 domain of mouse Eps8, and Drs. S. Cheng, M. Coggeshall, and J. Knight for helpful discussion. We are grateful to staff members of the Structural Biology Core Facility in the Institute of Biophysics, CAS, for their excellent technical assistance, and Z. Lou and Y. Han for help with data collection. This work was supported by an “863” project grant 2006AA02A322 and a CAS grant 2006C13911002 to X.L.; a CAS grant KSCX2-YW-05, an NSFC grant 30221003, and a MOST International Collaboration grant 2006DFB32420 to Z.R.; and an NIH grant NS044154 to K.H.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1789209.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Aitio O, Hellman M, Kesti T, Kleino I, Samuilova O, Paakkonen K, Tossavainen H, Saksela K, Permi P. Structural basis of PxxDY motif recognition in SH3 binding. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer H, Mayer H, Marchler-Bauer A, Salzer U, Prohaska R. Characterization of p40/GPR69A as a peripheral membrane protein related to the lantibiotic synthetase component C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:69–74. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blisnick T, Vincensini L, Barale JC, Namane A, Braun Breton C. LANCL1, an erythrocyte protein recruited to the Maurer's clefts during Plasmodium falciparum development. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;141:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AD, Olin B, Ridderstrom M, Mannervik B, Jones TA. Crystal structure of human glyoxalase I—Evidence for gene duplication and 3D domain swapping. EMBO J. 1997;16:3386–3395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee C, Paul M, Xie L, van der Donk WA. Biosynthesis and mode of action of lantibiotics. Chem Rev. 2005;105:633–684. doi: 10.1021/cr030105v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CH, Kurien BT, Mehta P, Mhatre M, Mou S, Pye QN, Stewart C, West M, Williamson KS, Post J, et al. Identification of lanthionine synthase C-like protein-1 as a prominent glutathione binding protein expressed in the mammalian central nervous system. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3262–3269. doi: 10.1021/bi061888s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disanza A, Carlier MF, Stradal TE, Didry D, Frittoli E, Confalonieri S, Croce A, Wehland J, Di Fiore PP, Scita G. Eps8 controls actin-based motility by capping the barbed ends of actin filaments. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1180–1188. doi: 10.1038/ncb1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob C, Lancaster JR, Giles GI. Reactive sulphur species in oxidative signal transduction. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:1015–1017. doi: 10.1042/BST0321015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Zhang P, Armstrong RN, Gilliland GL. The three-dimensional structure of a glutathione S-transferase from the mu gene class. Structural analysis of the binary complex of isoenzyme 3-3 and glutathione at 2.2-Å resolution. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10169–10184. doi: 10.1021/bi00157a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landlinger C, Salzer U, Prohaska R. Myristoylation of human LanC-like Protein 2 (LANCL2) is essential for the interaction with the plasma membrane and the increase in cellular sensitivity to adriamycin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1759–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Yu JP, Brunzelle JS, Moll GN, van der Donk WA, Nair SK. Structure and mechanism of the lantibiotic cyclase involved in nisin biosynthesis. Science. 2006;311:1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.1121422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lamb D, Chou MM, Liu YJ, Li G. Nerve growth factor-mediated neurite outgrowth via regulation of Rab5. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1375–1384. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer H, Breuss J, Ziegler S, Prohaska R. Molecular characterization and tissue-specific expression of a murine putative G-protein-coupled receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1399:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer H, Bauer H, Breuss J, Ziegler S, Prohaska R. Characterization of rat LANCL1, a novel member of the lanthionine synthetase C-like protein family, highly expressed in testis and brain. Gene. 2001;269:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongiovi AM, Romano PR, Panni S, Mendoza M, Wong WT, Musacchio A, Cesareni G, Di Fiore PP. A novel peptide–SH3 interaction. EMBO J. 1999;18:5300–5309. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offenhauser N, Castelletti D, Mapelli L, Soppo BE, Regondi MC, Rossi P, D'Angelo E, Frassoni C, Amadeo A, Tocchetti A, et al. Increased ethanol resistance and consumption in Eps8 knockout mice correlates with altered actin dynamics. Cell. 2006;127:213–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HW, Boduluri SR, Moomaw JF, Casey PJ, Beese LS. Crystal structure of protein farnesyltransferase at 2.25 angstrom resolution. Science. 1997;275:1800–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proepper C, Johannsen S, Liebau S, Dahl J, Vaida B, Bockmann J, Kreutz MR, Gundelfinger ED, Boeckers TM. Abelson interacting protein 1 (Abi-1) is essential for dendrite morphogenesis and synapse formation. EMBO J. 2007;26:1397–1409. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scita G, Nordstrom J, Carbone R, Tenca P, Giardina G, Gutkind S, Bjarnegard M, Betsholtz C, Di Fiore PP. EPS8 and E3B1 transduce signals from Ras to Rac. Nature. 1999;401:290–293. doi: 10.1038/45822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Kato H, Hata Y, Nishioka T, Kimura A, Oda J, Katsube Y. Three-dimensional structure of the glutathione synthetase from Escherichia coli B at 2.0 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:1083–1100. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]