Abstract

Objective

Mediators of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and HIV risk behavior were examined for men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM).

Method

Data from a dual frame survey of urban MSM (N = 1078) provided prevalence estimates of CSA, and a test of two latent variable models (defined by partner type) of CSA-risk behavior mediators.

Results

A 20% prevalence of CSA was reported. For MSM in secondary sexual relationships, our modeling work identified two over-arching but inter-related pathways (e.g., both pathways include effects on interpersonal skills) linking CSA and high-risk behavior: 1) CSA-Motivation-Scripts-Skills-Risk Behavior, and 2) CSA-Motivation-Coping-Risk Appraisal-Skills-Risk Behavior. For men in primary relationships, there was one over-arching pathway including CSA-Motivation-Coping-Risk Appraisal- Risk Behavior processes. Exploratory analyses indicated that men with a history of CSA in only primary relationships vs only secondary relationships had, for example, fewer motivational problems, and better coping and interpersonal skills.

Conclusions

CSA contributes to the ongoing HIV epidemic among MSM by distorting or undermining critical motivational, coping, and interpersonal factors that, in turn, influence adult sexual risk behavior. Further, the type of adult relationships men engage serve as markers for adult CSA-related problems. The findings are discussed in the context of current theory and HIV prevention strategies.

Practice Implications

Direct extrapolation from our findings to practice is limited. However, there are general implications that may be drawn. First, the complex challenges faced by men with severe CSA experiences may limit the effectiveness of typical short-term HIV risk reduction programs; more intensive treatment may be needed. Secondly, Clinical Psychologists and Psychiatrists with MSM patients with CSA histories should, if not already, routinely consider issues of sexual health; patterns and types of sexual partners may be useful markers for identifying more problematic cases. Lastly, public service messages directed at destigmatizing CSA for MSM may increase use of health and mental health services.

Keywords: Childhood sexual abuse, Men who have sex with men, Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome, Risk behavior

Introduction

Overview

Men who have sex with men (MSM) report a high prevalence of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) (20%), with more than 80% of MSM reporting severe CSA experiences involving penetrative sex, and/or use of violence and force (Paul, Catania, Pollack, & Stall, 2001). The present study (2003) confirms these prevalence estimates (see results). Heretofore, this level of CSA was observed only among heterosexual women, although not nearly as many female victims (20%) as MSM (80%) are exposed to severe forms of CSA (Paul et al., 2001; Paul, Malow, Dolezal, & Carballo-Dieguez, 2004) (comparisons controlling for CSA definition). The present study examines the impact of CSA on social and psychological factors that effect HIV spread among MSM.

Since the 1980s HIV infection has spread widely among adult MSM (Catania, Canchola, Pollack, & Chang, 2001; Catania, Morin, Canchola, Pollack, Chang, & Coates, 2000), with current prevalence levels estimated at approximately 28% (Osmond, Pollack, Paul, & Catania, 2007). This enduring HIV epidemic is attributed to various causes, a major factor being reductions in risk concerns related to the availability of better treatment (Huebner, Rebchook, & Kegeles, 2004). However, it is difficult to explain why HIV incidence rates among MSM, even prior to current treatment advances, have been relatively stable and at levels not seen outside of sub-Saharan Africa (Catania et al., 2000). Prior studies suggest that CSA influences HIV spread among MSM (e.g., Jinich, Paul, Stall, Acree, Kegeles, Hoff, & Coates, 1998; Johnsen & Harlow, 1996; Paul, Catania, Pollack, & Stall, 2001). We suggest that the high prevalence of CSA in this population has contributed to psychosocial conditions that, in turn, have sustained the HIV epidemic over several decades.

Adult MSM with CSA histories, relative to men without such histories, have significantly greater levels of high-risk sexual behavior and higher HIV prevalence, in addition to social and mental health problems that impact HIV risk (Carballo-Dieguez & Dolezal, 1995; Catania & Paul, 1999; DiIorio, Hartwell, & Hansen, 2002; O'Leary, Purcell, Remien, & Gomez, 2003; Paul et al., 2001; Purcell et al., 2004; Stall et al., 2003). Gaining an understanding of the processes that mediate between CSA and adult health problems is an important initial step in developing appropriate prevention programs and treatment strategies.

Prior research on adult MSM indicates that the CSA and HIV risk behavior relationship is mediated by affective and sexual motivations, coping responses, risk appraisals, and interpersonal factors (O'Leary et al., 2003; Paul et al., 2001). Previous studies, however, are limited in scope and have not used more powerful analytic techniques. The present investigation examined multiple indicators of a broad array of mediators using structural equation modeling (SEM). The proposed model synthesizes concepts from social learning theory (Catania & Paul, 1999; Hoier et al., 1992), emotion-coping theory (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988a; Lazarus, 1991), and HIV risk reduction models (Catania, Binson, Dolcini, Moskowitz, & van der Straten, 2001; Catania, Kegeles, & Coates, 1990; Fisher & Fisher, 1992; Prochaska, Redding, Harlow, Rossi, & Velicer, 1994).

The proposed model links CSA to HIV-risk behavior through pathways mediated by motivations, coping responses, risk appraisals, interpersonal-regulatory abilities, and sexual scripts (see below). We have limited our analysis to model components amenable to intervention and are representative (not exhaustive) mediators of CSA-risk behavior pathways. The proposed model is tested separately for sexual experiences with primary or secondary sexual partners. Theory and empirical studies suggest that some antecedents of risk or enactment differ in importance across these two situations (Catania, Coates, & Kegeles, 1994; Reisen & Poppen, 1999); see for review (Misovich, Fisher, & Fisher, 1997). The proposed model has applicability to HIV positive and negative men. (Note. The dependent variable in the SEM models incorporates HIV status of the respondent in its construction, therefore, HIV status is not included as an independent variable).

Supplemental materials detailing the underlying model linking CSA to adult sexual behavior for MSM is available from the author. Here we summarize key elements of this heuristic model and in the following sections describe theoretical linkages among key elements in the context of CSA. As noted above, the model is limited to five general mediating factors: 1) motivational forces, 2) coping responses, 3) risk appraisals, 4) interpersonal skills, and 5) sexual scripts. Motivational forces are delineated into four additional components represented by observed (measured) variables (i.e., the observed variable universe is larger than examined, but for practical and theoretical reasons the list was necessarily limited; see Table 1), and include the following components: a) Sexual motivation [Observed Variables (OV): sexual compulsion, sexual preoccupation, self-validation through sex)], b) Interpersonal-approval motive referred to here as “other directedness” to emphasize the potential effects of CSA on exaggerated approval seeking from others through attempts to make one’s self more appealing to the other person (OV: Impression management), c) Interpersonal-Affective motivation (OV: Interpersonal Anger; anger towards others as differentiated from anger towards self, Siegel, 1986), and d) Affective motivation (OV : depressive affect).

Table 1.

Measures Within Each Factor

| Childhood Sexual Abuse (high score = greater severity) | |||||||

| Measure (Data Source) | References | Categories | |||||

| Scale of CSA Victimization (TI) | Whitmire et al. (1999); Wyatt (1985) | No CSA (69%), Non-penetrative sex (8%), | |||||

| Penetrative sex (23%) | |||||||

| Number of CSA Occasions (TI) | Paul et al. (2001) | None (69%), 1–5 times (21%), 6+ times (10%) | |||||

| Number of Perpetrators (TI) | Paul et al. (2001) | None (69%), One (19%), Two or more (13%) | |||||

| Age When First Victimized (TI) | Paul et al. (2001) | No CSA (69%), Age 12–17 (12%), Before age 12 (19%) | |||||

| Level of Coercion Experienced (TI) | Paul et al. (2001) | No CSA (69%), No pressure (1%), Other pressure | |||||

| (16%) | |||||||

| Threat of harm (3%), Use of weapon or physical force | |||||||

| (12%) | |||||||

| Affective Motive (high score = greater affect, e.g., more depressed) | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Modified CES-D Depression Scale (TI) | Radloff (1977) | 8 | 0.8540 | 0–4 | 1.469 | 0.815 | |

| Interpersonal-Affective Motive: Anger (high score = more frequent and intense feelings of anger) | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Anger Arousal Scale (SAQ) | Siegel (1986) | 6 | .8056 | 1–4 | 1.647 | 0.594 | |

| Anger-In Scale (SAQ) | Siegel (1986) | 4 | .7089 | 1–4 | 1.721 | 0.628 | |

| Sexual Motives (high score = greater preoccupation, impulsivity, value | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Sexual Preoccupation Scale (SAQ) | Snell and Papini (1989) | 6 | 0.7687 | 1–4 | 2.625 | 0.564 | |

| Sexual Impulsivity Scale (SAQ) | Exner, Meyer-Bahlburg, & Ehrhardt (1992) | 4 | 0.6664 | 1–4 | 1.579 | 0.558 | |

| Feeling Valued By One’s Partner (SAQ) | Hill and Preston (1996) | 4 | 0.7193 | 1–4 | 2.302 | 0.691 | |

| Interpersonal Social Approval Seeking Motive: Other-directedness (high score = more inclined to be more “other-directed”)1 | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| BIDR Impression Management Subscale (SAQ) | Paulhus (1984); Paulhus (1988) | 14 | .7527 | 1–4 | 2.684 | 0.468 | |

| Behavioral Escape-Avoidance Coping (high score = more frequent use) | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Ways of Coping Substance Use (SAQ) | Carver, Scheir, Weintraub (1989); | …‥4 | .9432 | 1–4 | 1.820 | 0.838 | |

| Folkman et al. (1988a;b) | |||||||

| Categories | |||||||

| Alcohol Use in Past 6 Months (SAQ) | Cahalan (1970) | Abstain (17%), Occasional (27%), Light (50%), Heavy (6%) | |||||

| Drug Use in Past 6 Months | Catania et al. (2001) | Abstain (35%), Monthly (24%), Weekly (16%), | |||||

| Up to 3 times a week (11%), >3 times a week (14%) | |||||||

| Cognitive Escape-Avoidance Coping (high score = more frequent use)2 | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Ways of Coping Denial (SAQ) | Carver et al. (1989); | 4 | .7907 | 1–4 | 1.414 | 0.515 | |

| Ways of Coping Behavioral Disengagement (SAQ) | Carver et al. (1989) | 4 | .7828 | 1–4 | 1.849 | 0.585 | |

| TSI Dissociation Scale (SAQ) | Briere, Elliott, Harris,& Cotman (1995) | 9 | .8649 | 1–4 | 1.862 | 0.561 | |

| TDI Defensive Avoidance Scale (SAQ) | Briere et al., (1995) | 8 | .9139 | 1–4 | 2.168 | 0.690 | |

| Adaptive or Problem-Focused Coping (high score = more frequent use)3 | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Instrumental Social Support (SAQ) | Carver et al. (1989) | 4 | .8223 | 1–4 | 2.988 | 0.653 | |

| Emotional Social Support (SAQ) | Carver et al. (1989) | 4 | .8834 | 1–4 | 3.056 | 0.713 | |

| Risk Appraisal (high score = greater concern with contracting HIV/STD)4 | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Fear of AIDS Scale (SAQ) | Snell and Finney (1998) | 4 | .7969 | 1–4 | 2.657 | 0.835 | |

| Sexual Script (high score = more sexually aggressive) | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Experiencing Power of One’s Partner (SAQ) | Hill and Preston (1996) | 4 | .8368 | 1–4 | 2.161 | 0.801 | |

| Enhancing One’s Feelings of Power (SAQ) | Hill and Preston (1996) | 4 | .7062 | 1–4 | 1.942 | 0.640 | |

| Attitude Towards the Use of Sexual Force (SAQ) | Spence, Losoff, & Robbins. (1991) | 4 | .6337 | 1–4 | 1.312 | 0.423 | |

| Interpersonal Regulatory Sexual Skills (high score = more assertive) | |||||||

| Measure | References | #Items | Alpha | Range | Mean | SD | |

| Dyadic Sexual Regulation Scale (TI) | Catania, McDermott & Wood. (1984) | 6 | .5460 | 1–4 | 3.124 | 0.499 | |

| Sexual Assertiveness Scale (TI) | Kirby (1998) | 5 | .7999 | 1–4 | 3.378 | 0.575 | |

| Categories | |||||||

| If you were thinking about having anal intercourse | de Vroome, de Wit, Stroebe, Sandfort, (1998) | …Disagree a lot (3%), Kind of disagree (4%), Kind of agree | |||||

| (8%), | |||||||

| with a man for the first time, you would make | ….Agree a lot (85%) | ||||||

| sure you had condoms to use.5 | |||||||

Note. TI=Telephone Interview, SAQ=Self-Administered Questionnaire.

The Safe Sex-Related Impression Management Scale (van der Straten, Catania, & Pollack., 1998) was not included in the analysis because the items composing the scale elicited unexpectedly large amounts of non-response, resulting in missing scale scores for 65% of respondents.

The Carver Coping Mental Disengagement scale was not included in the analysis because it failed to meet the threshold for internal consistency, which was operationalized as having a Cronbach’s Alpha > .50.

The Carver Coping Restraint scale was dropped during assessment of the measurement model because it failed to meet the threshold for inclusion in the latent factor, operationalized as having a standardized factor loading > .40.

This latent factor failed to converge with both scale scores (Play Down Risk and Fear of AIDS scales in the model. Only the Fear of AIDS Scale was utilized (higher reliability).

This item was part of the Condom Use Assertiveness Scale (de Vroome et al., 1998). The total scale was not included in the model because it failed to meet the threshold for internal consistency, which was operationalized as having a Cronbach’s Alpha > .50.

Coping responses were delineated into a) Cognitive escape-avoidance coping (OV: denial, disengagement, dissociation, defensive avoidance), b) Behavioral escape-avoidance coping (OV: Alcohol, drug use), and c) Adaptive or problem solving coping (instrumental and emotional social support). Risk appraisals focused specifically on perceived risks regarding contracting or spreading HIV (OV: fear of AIDS).

Sexual scripts included representations of particular sexual styles of sexual interaction relevant to men with CSA histories including passive/powerless and aggressive sexual styles (OV: power in sexual interactions, attitudes towards sexual aggression). Interpersonal regulatory skills included consideration of the ability to influence what transpires in the sexual interaction and health protective behavior in the sexual relationship (OV: dyad sexual regulation, assertiveness, condom preparedness).

CSA and adult sexual outcomes

The present model, specific to sexuality, builds on the general theoretical work of Hoier and colleagues (Hoier et al., 1992). Hoier et al., postulate that CSA, particularly severe CSA, [e.g., involving penetrative sex over multiple occasions (Bukowski, 1992; Finkelhor, 1994; Kilpatrick, 1992; Tolan & Henry, 1996), elicits flight/fright responses in the child under conditions that prevent the victim from acting successfully to change the aversive situation, and which also punish efforts by the victim to change matters. Among other outcomes, these conditions may lead to learned helplessness, powerlessness, low self-efficacy beliefs and associated motivational deficits; all of which may be associated with poor interpersonal-regulatory capabilities in adulthood. These conditions may also lead to the development of coping strategies (e.g., cognitive or behavioral escape-avoidance strategies) that inhibit health protective risk appraisals. (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b) (also see Jinich et al., 1998; Lipovsky & Kilpatrick, 1992; Purcell et al., 2004)(Lee, 1998; Quina, Morokoff, Harlow, & Zurgriggen, 2004). For instance, underestimating risks to health and wellbeing may facilitate sexual revictimization in adulthood (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986; DiIorio et al., 2002; Kalichman et al., 2001; Paul et al., 2001; Purcell et al., 2004). Alternatively, adaptive coping strategies (e.g., social support seeking) may reduce risk by facilitating accurate risk appraisals through the expressed concerns and observations of friends (Catania et al., 1990).

CSA victims may acquire the belief that they are unable to control their own sexual feelings (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985). That is, the perpetrator may elicit sexual arousal in the victim under conditions in which the victim is helpless to “not respond” sexually. The use of rewards (gifts, attention) by the perpetrator may result in victims learning self-schema and values that over-emphasize sexual interaction with others. In adulthood, these circumstances may lead to a preoccupation with sex, poor sexual impulse control, and a heightened perception that sexual interaction is necessary in order to be valued by others (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986). The salience of sexual-interpersonal motivations may vary depending on the type of sexual relationship. In short-term relationships, such as one-night stands, the relationship may be primarily motivated by sexual gratification needs (Misovich et al., 1997). In longer-term relationships, wherein interpersonal goals of maintaining and enhancing the relationship may be more relevant, interpersonal motivations may be equal to or stronger than sexual motivations in influencing risk appraisals (Misovich et al., 1997).

In addition, perpetrators may be powerful models of sexually aggressive behavior and poor interpersonal-anger control. Among CSA victims, therefore, patterns of sexual aggression and helplessness may manifest in adulthood in the form of sexual scripts that reflect polarized “styles” of aggressive or passive sexual interaction. When the sexual abuse extends across multiple occasions, victims may also learn to avoid punishment by focusing their attention on how the perpetrator(s) views the victim and, consequently, victims may modify their behavior to accommodate the perpetrator’s expectations and beliefs (i.e., becoming more approval seeking or “other” vs. “inner” directed). This accommodation may be enhanced by the erosion of self-worth that often results from CSA victimization. In adulthood, CSA victims may be overly sensitive to others’ opinions, and attempt to seek other’s approval with out regard to their personal well-being (e.g., avoiding emotional or physical rejection by doing things to please sexual partners without regard for one’s own health).

Repeated occurrences of CSA, with intermittent rewards (e.g., gifts, attention) by the abuser(s), may strengthen underlying learning contingencies that lead to enduring maladaptive emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses [e.g., depression; depressive mood is associated with sexual risk taking, and this effect may be mediated by coping responses (Marks, Bingman, & Duval, 1998; Miller, 1999)], and generalization of such response patterns across social situations (Hoier et al., 1992). Thus, CSA-related responses may remain durable into adulthood. Cross situational generalizability of CSA-related responses may lead to “trait-like” or rigid emotional, cognitive, and behavioral response patterns across situations (Hoier et al., 1992). Since the CSA trauma-related learning conditions involve sex, then sexual stimuli may be particularly powerful in eliciting extreme responses. For instance, MSMs with CSA histories may show characteristically higher levels of interpersonal-anger than nonCSA MSMs particularly in intimate situations. In brief, a social learning analysis suggests that CSA, among other outcomes, produces distortions in fundamental motivational processes. In the present study, we restrict our examination to motivational pathways that are theoretically important and prevention amenable linkages between CSA outcomes and risk behavior.

Summary of hypothesized pathways and relevant background literature

i) CSA will affect (a) motivations, (b) coping, and (c) sexual scripts and interpersonal (sexual) regulatory skills

More severe CSA will be associated with greater interpersonal anger, sexual impulsiveness/preoccupation, depressive affect, and “other-directed” interpersonal motives. More severe CSA will also be associated with less use of adaptive coping and more frequent use of cognitive and behavioral escape avoidance coping, with more passive/aggressive sexual scripts, and poorer interpersonal (sexual) regulatory skills.

ii) Motivations will influence coping strategies

Greater interpersonal anger,sexual impulsiveness/preoccupation, depression, and “other-directed” interpersonal motivation will be associated with less frequent use of adaptive coping, and more frequent use of cognitive and behavioral escape avoidance coping.

iii) Motivations and coping will influence risk appraisals

Greater sexual impulsiveness/preoccupation, greater “other-directedness” less frequent use of adaptive coping, and more frequent use of cognitive and behavioral escape avoidance coping will be associated with lower risk appraisals of potentially unsafe sexual encounters.

iv) Motivations and coping will influence sexual scripts and interpersonal (sexual) regulatory skills

Greater sexual impulsiveness/preoccupation, greater “other-directedness” and more frequent use of escape avoidance coping will be associated with either more submissive or aggressive scripts, and poorer interpersonal (sexual) regulatory skills.

v) Risk Appraisals will influence interpersonal (sexual) regulatory skills

Higher risk appraisals will be associated with better interpersonal (sexual) regulatory skills.

vi) Risk appraisals, sexual scripts, and interpersonal sexual skills will influence high-risk sexual behavior

Higher risk appraisals, more moderate sexual scripts (neither highly submissive nor aggressive), and good interpersonal (sexual) regulatory skills will be associated with less high-risk behavior.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected in San Francisco (Urban Men’s Health Study III) from May 24, 2002, to January 19, 2003 using a dual frame sample that combines a household probability sample (random digit dial, RDD), and a list sample of MSM reporting CSA from a prior household survey (Total Sample RDD (N = 879) + List (N = 199) = 1078). Respondents (both samples combined) ranged in age from 18–90 years (62% over 40 yrs.), 79% were Non-hispanic white (11% Hispanic, 4% nonHispanic African American, 4% nonHispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, 3% Mixed and <1% Native American), Median income >$50,000/yr., and 62% reported working full-time. Westat Corporation constructed the sample frame and participated in data collection. Details of the sampling methodology are described elsewhere (Binson, Moskowitz, Mills, Anderson, Paul, Stall, & Catania, 1996; Catania, Osmond, Stall, Pollack, Paul, Blower, Binson, Canchola, Mills, Fisher, Choi, Porco, Turner, Blair, Henne, Bye, & Coates, 2001) (see methodological report available from the first author). MSM were defined so as to include men who were more closeted [reporting same gender sex (of any kind) since age 14 or, if never sexually active, those who defined themselves as gay/bisexual]. Prevalence estimates are based on the probability sample (N = 879), and modeling work is based on the combined samples limited to sexually active men with male partners in the past year (N = 762 of the original 1078). Two models are examined: MSM with secondary partners (N = 602), and MSM with Primary partners (N = 417). A total sample of 762 cases were eligible for the current modeling analysis (Note. 251 participants had both primary and secondary partners and are included in each model, 33% overlap; this strategy reflects the empirically demonstrated differences in risk behavior and correlates of risk behavior between secondary and primary partner situations; (Catania, Coates, & Kegeles, 1994; Reisen & Poppen, 1999); see for review (Misovich, Fisher, & Fisher, 1997). Thus, our models do not reflect different types of individuals per se, rather they reflect the types of sexual situations of import. A consequence of this approach is that the models can not be statistically compared (i.e., we cannot test if the effect sizes are larger in one model vs. another), but conceptually the results can be contrasted (a relationship holds across models or diverges across models) which is of substantive importance.

Data collection

Respondents participated in an initial telephone interview (cooperation rate = 74%) followed by a self-administered mail questionnaire (received within 1–2 weeks of completing the phone interview; cooperation rate = 85%). Participants were provided informed consent with procedures approved by UCSF’s and Westat’s IRBs. Additional data collection details are available from the first author. A licensed clinician was on-call at all times to offer immediate counseling to respondents if needed. One respondent sought counseling with the on-call therapist for distress unrelated to the interview questions.

Measures

Overview

Measures for the present study were recommended and reviewed by a panel of experts; proposed measures were adapted as needed for use with MSM participants and reduced based on published factor analytic studies. Scale development and modifications procedures are available from the first author. All measures were administered in English and Spanish. Since the measures were evaluated further after data collection and required to meet requirements for internal consistency and appropriateness regards representation of the latent factors (see Statistical Methods below), not all the measures administered to respondents were included in the final models. Table 1 summarizes study measures by each latent factor. The complete survey instruments are available from the first author. Only the dependent variable and CSA related measures are described in detail here, for all other measures see Table 1.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is dichotomized (1 = Risky Sex, 0 = No Risky Sex) with high-risk sex defined as an HIV-positive respondent having unprotected insertive anal intercourse with an HIV-negative or serostatus-unknown partner, or an HIV-negative respondent having unprotected receptive anal intercourse with an HIV-positive or serostatus-unknown partner. All sexual behaviors were differentiated by 1) insertive and receptive, 2) condom use, non-condom use with withdrawal, and non-condom use with ejaculation and 3) type of sexual partner. The dependent variable was derived from estimates based on a partner-by-partner assessment of sexual behaviors with the four most recent sexual partners including a primary sexual partner if applicable. A primary sexual partner was defined as a partner with whom the respondent indicated that they were in love and had a special commitment; secondary partners were all other sexual partners. The precision in this measurement approach is considered adequate (Catania, Osmond, Neilands, Canchola, Gregorich, & Shiboski, 2005); similar measures have been used in the past, and are correlated with HIV infection among MSM (Catania, et al., 2001).

Childhood sexual abuse/trauma

The present definition of sexual abuse has been discussed previously (Paul et al., 2001). Respondents were classified as having had a history of CSA if they reported “…ever been forced or frightened by someone into doing something sexually that you did not want to do” before age 18 (“These next questions are about unwanted sexual experiences before age 18. If you've had any such experiences, they may be difficult to discuss and I appreciate your willingness to answer these questions. Unwanted sexual experiences could include being forced to watch someone having sex, being forced or frightened into touching someone or having them touch you sexually, or being forced or frightened into some other type of sexual activity including oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse or mutual masturbation. Thinking back to your childhood and adolescence before age 18, during those years, were you ever forced or frightened by someone into doing something sexually that you did not want to do?”). The interviewer script and training emphasized the need for being gentle in asking this question. If the respondent answered “no”, or “don’t know”, or declined to answer, we asked an additional question which if they answered “yes” to also qualified them as having been sexually abused prior to age 18 (“Sometimes people's views about their experiences change over time. Did you ever have an experience before age 18 when you felt at the time that you were forced or frightened into doing something sexually that you did not want to do?”). The measurement approach utilized in the present study is supported by prior studies (Banyard & Williams, 1996; Lipovsky & Kilpatrick, 1992; Wyatt & Peters, 1986; Jinich et al., 1998; Finkelhor, Moore, Hamby, & Straus, 1997; Whitmire, Harlow, Quina, & Morokoff, 1999). The validity and reliability of retrospective measures of CSA and related characteristics are substantiated by cross sectional and longitudinal studies showing that CSA is consistently correlated with sexual risk behaviors and antecedents of those behaviors (Jinich et al., 1998; Johnsen & Harlow, 1996; Loferski, Quina, Harlow, & Morokoff, 1992; Paul et al., 2001; Whitmire et al., 1999).

Child/Adolescent sexual abuse (CSA): Severity of trauma

CSA severity was represented by multiple measures. We adapted Whitmire et al.’s (4) CSA severity measure for heterosexual women to be used with male MSM victims. The Whitmire scale is based on literature indicating that more severe trauma is associated with penetrative sexual acts (Purcell et al., 2004; Whitmire et al., 1999). Consequently, the scale was scored 1 = No CSA, 2 = nonpenetrative sexual abuse, 3 = penetrative sexual abuse. Based on work by Paul et al., (2001) and others (e.g., Purcell et al., 2004), we included other indicators of CSA severity that are associated with long-term difficulties in other population segments including MSM: the number of times the person was sexually abused, the number of perpetrators, and the level of coercion experienced (no CSA = 1 to use of weapons or physical force = 5; see Table 1 for further details).

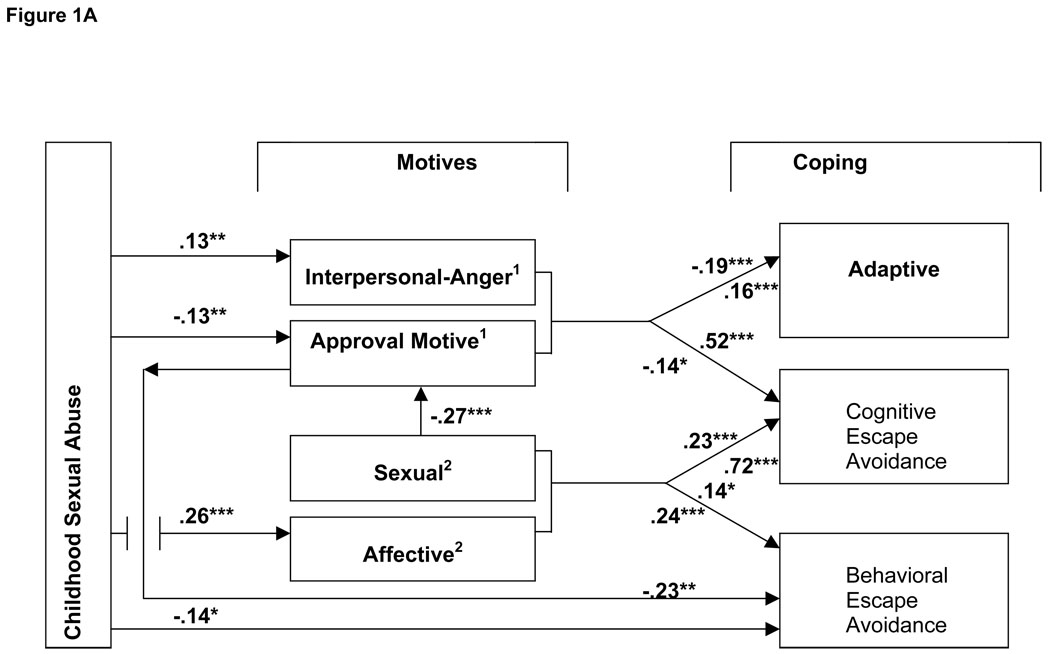

Statistical methods

Structural Equation Modeling. Separate structural equation models were evaluated for secondary and primary sexual partners using Mplus Version 2.14 which allows for imputation for all preliminary estimation and modeling, and then Version 3.0; we used the WLSMV estimator (Muthén & Muthén, 2001). Further analytic details are available from the first author. Given the exploratory nature of the proposed analyses (see Vandenberg & Lance, 2000), good fit was indicated by a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993) value below .08, and Comparative Fit Index values above .90 (CFI; (Bentler, 1990) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) (Tucker & Lewis, 1973) (as suggested by Hatcher & Stepanski, 1994). Each structural model was fitted as originally proposed. Significant pathways (p<.10) that improve fit (as assessed by the RMSEA, CFI, and TLI) were retained in the model. We re-fit the final models to each of ten remaining imputed data sets, the results of which form the basis for statistical inference. The completion of this process identified the final structural equation models shown in Figure 1A–Figure 2B.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A

The effects of CSA on high risk sex with secondary sexual partners: Relationships among CSA, motivations, and coping strategies.

Note. All coefficients are standardized.

1Top value = Anger; Bottom value = Approval Motive (Impression Management).

2Top value = Sexual Motives; Bottom value = Affective Motives (Depression) RMSEA = .074, CFI = .988, TLI = .991.

p = .10†, .05*, .01**, .001***, N = 602.

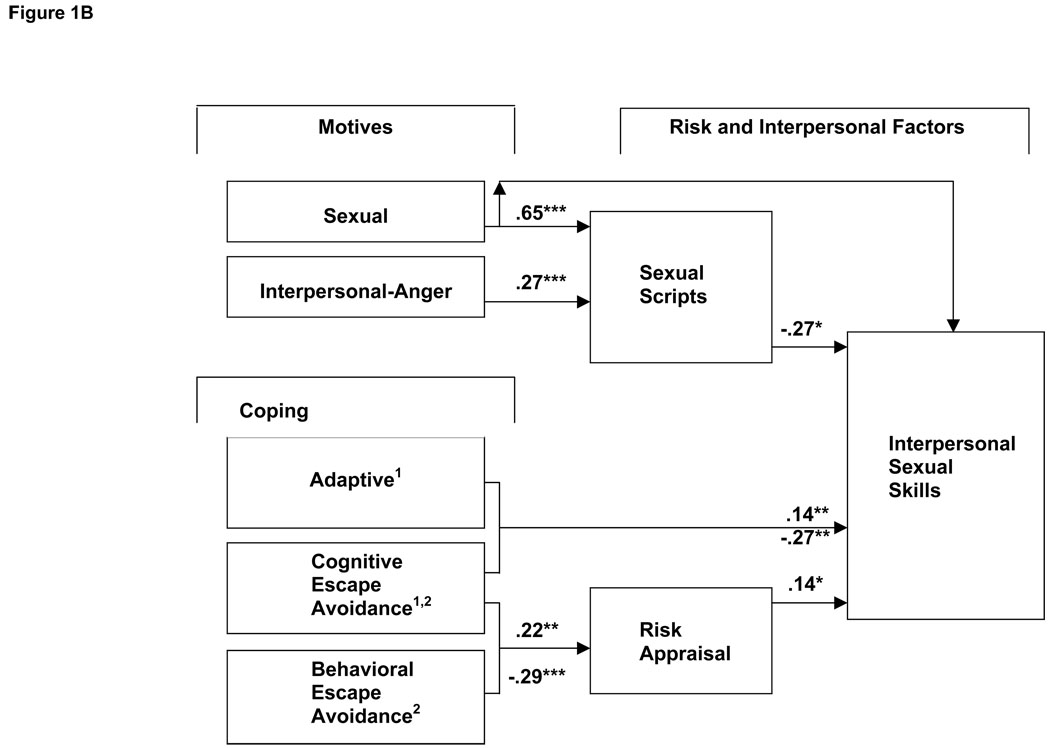

Figure 1B

The effects of CSA on high risk sex with secondary sexual partners: Relationships among sexual skill, sexual scripts, risk appraisals, and prior model components (motives, coping).

Note. All coefficients are standardized; Not all CSA, motive, coping relationships are shown.

1Top value = Adaptive coping; Bottom value = Cognitive escape avoidance.

2Top value = Cognitive escape avoidance, Coping; Bottom value = Behavioral escape avoidance.

p = .10†, .05*, .01**, .001***.

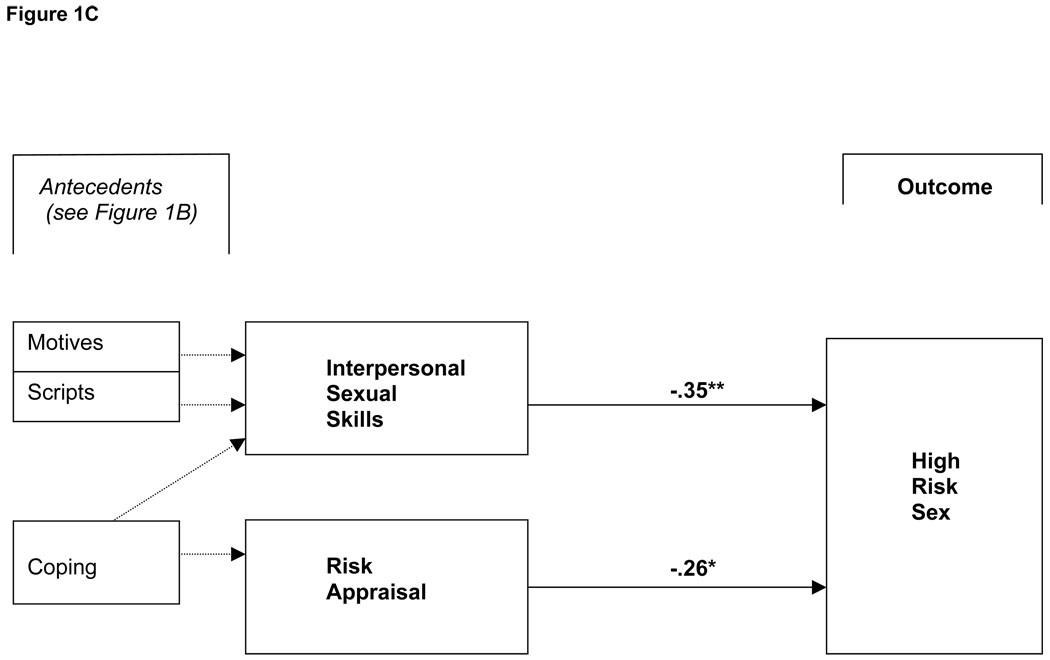

Figure 1C

The effects of CSA on high risk sex with secondary sexual partners: Proximal antecedents of high risk sex.

Note. Distal antecedents not shown. See figures 1A and 1B.

p = .10†, .05*, .01**, .001***.

Figure 2.

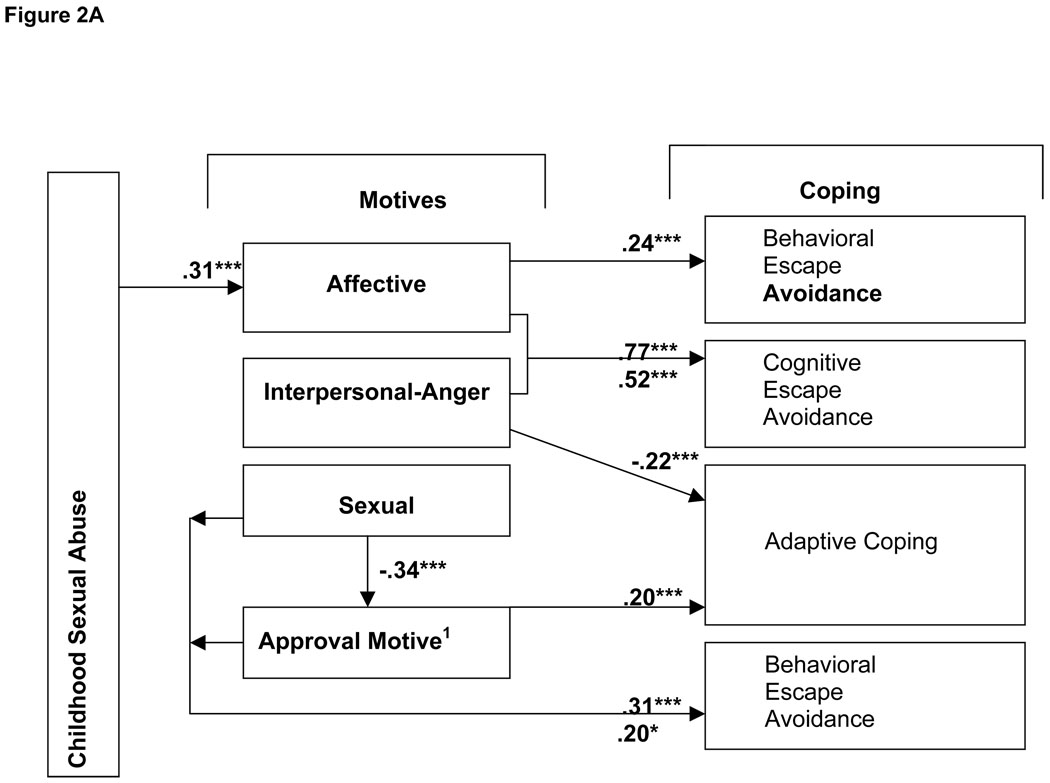

Figure 2A

The effects of CSA on high risk sex with primary sexual partners: CSA, Motives, and Coping Pathways.

Note. Models described in 2A and 2B are actually one model broken into two panels for ease of presentation.

N = 417, RMSEA = .080, CFI = .991, TLI = .992.

p = .10†, .05*, .01**, .001***.

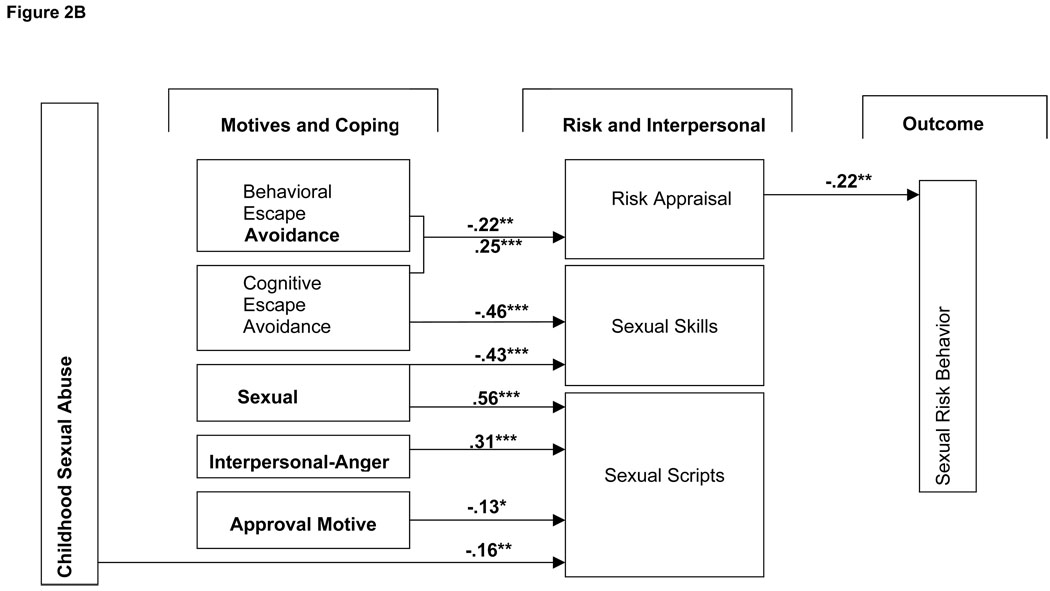

Figure 2B

The effects of CSA on high-risk sex with primary sexual partners: Motives, Coping, Risk, Social, and Outcome Pathways.

Note. Models described in 2A and 2B are actually one model broken into two panels for ease of presentation.

N = 417, RMSEA = .080, CFI = .991, TLI = .992.

p = .10†, .05*, .01**, .001***.

See 2A for pathways linking CSA, Motives, and Coping.

Results

Prevalence of CSA

Approximately 22% (n = 879) of MSM reported a history of CSA (before age 17 years) in the overall household probability sample. By including the list sample, the total proportion of CSA cases increases to 30% for the model concerning secondary sexual partners, and 32% for the model concerning primary sexual partners.

Secondary sexual partner model

Among men reporting secondary sexual partners, 9% reported high-risk sex with a secondary sexual partner. Approximately 66% of respondents with one or more secondary sexual partners did not know at least one partner’s HIV serostatus; 47% of dyads involved a secondary sexual partner of unknown HIV serostatus. The CFI and TLI for the final structural equation model exceed .98 and .99 respectively, and RMSEA is .074, indicating adequate fit given the exploratory nature of the data analysis (Figures 1A–1C).

Motivations

CSA was associated with interpersonal-affective, affective, and interpersonal-approval seeking motivations and coping, such that more severe CSA was associated with greater anger and depressive mood, less “other-directedness,” and less frequent use of behavioral escape avoidance coping; CSA was unrelated to sexual motivations (see Figure 1A). Although CSA was unrelated to sexual motivation, sexual motivation significantly impacted other motivational and coping factors in the model that involve CSA as an antecedent. That is, at the observed variable level, more sexually compulsive/obsessed men were significantly less “other-directed,” more frequently used cognitive/behavioral escape avoidance coping strategies, and reported significantly more sexually aggressive scripts (Figures 1A & 1B). Consistent with coping theory, CSA-Motivational pathways significantly impacted coping (see Figure 1A). Greater interpersonal-anger was associated with less use of adaptive coping and more cognitive escape avoidance coping, and greater use of sexually aggressive scripts. Being more “other-directed” was associated with more frequent use of adaptive coping and less use of cognitive escape avoidance coping. Cognitive escape avoidance coping was also influenced by affective motivation, with greater frequency of this coping response associated with greater depressive affect.

Coping

With respect to the secondary partners model, coping factors influenced risk appraisal and interpersonal sexual skills (See Figure 1B). More frequent use of adaptive coping strategies was significantly related to better interpersonal sexual skills, but unrelated to risk appraisal. More frequent use of behavioral escape avoidance coping strategies were associated with less concern with HIV risks. More frequent use of cognitive escape avoidance coping strategies, however, was significantly associated with greater concern with HIV risk, and with poorer interpersonal sexual skills.

Risk appraisal, interpersonal factors, risk behavior

Risk Appraisal significantly affects interpersonal sexual skills and risk behavior, such that greater concern is associated with better skill levels, and lower levels of high-risk sex (See Figures 1B & 1C). Sexual scripts, in turn, significantly influence interpersonal skills (See Figure 1B). Less aggressive sexual scripts are significantly related to better interpersonal skills which, in turn, are related to lower levels of risk behavior.

Primary sexual partner model

Among men with primary partners, 4% reported high-risk sex with a primary partner. Approximately 8% of respondents with primary partners did not know their partner’s HIV serostatus. The CFI and TLI for the final structural equation model exceeds .99 and RMSEA is .08, indicating adequate fit given the exploratory nature of the data analysis (see Figures 2A–2B).

Motivations

For men in primary sexual relationships (i.e., committed love relationships), CSA was associated with affective motivation, such that increasing severity of CSA was significantly associated with higher levels of depressive mood. Greater levels of depressive mood were significantly related to more frequent use of both types of escape avoidance coping strategies (See Figure 2A). In contrast to the secondary partner model, there was no direct impact of CSA on interpersonal-affective or interpersonal-approval seeking motivation (i.e., respectively interpersonal-anger, “other-directedness”), but the models were similar in showing no affect of CSA on sexual motives (See Figure 2A). Because, these latter motivations significantly impact factors further down the CSA-behavior causal chain (e.g., sexual scripts) (See Figure 2B), we retained all motivational factors in the model.

Nonmediating motivations

Although interpersonal-affective (interpersonal-anger), sexual, and interpersonal-approval seeking motives (“other-directedness”) did not mediate CSA and risk behavior for men in primary relationships, they did have significant effects on model factors that do mediate CSA-risk behavior relations (See Figure 2A). Men who were more other-directed were significantly more likely to use adaptive coping, less likely to use cognitive escape avoidance coping, and more likely to use behavioral escape avoidance coping strategies. Higher levels of sexual compulsivity/obsessiveness were significantly associated with being less “other-directed”, with more frequent use of cognitive escape avoidance coping and behavioral escape avoidance coping strategies, but were unrelated to adaptive coping. High levels of interpersonal-anger were significantly related to less frequent use of adaptive coping, and more frequent use of cognitive escape avoidance coping strategies, but unrelated to behavioral escape avoidance coping. Interpersonal-affective (anger), sexual, and interpersonal-approval seeking motives (“other-directedness”) also had differential effects on scripts or skills (See Figure 2B). That is, Greater interpersonal-anger, higher levels of sexual compulsivity/obsessiveness, and being more “inner-directed” were associated with more aggressive sexual scripts. Higher levels of sexual compulsivity were also significantly correlated with lower levels of interpersonal sexual skills.

Coping

As noted above there is a significant pathway from CSA and affective motivation to both cognitive and behavioral escape avoidance coping strategies. These coping strategies, in turn, have significant effects on risk appraisal and interpersonal sexual skills (See Figure 2B). The effects of coping on these latter outcomes are not uniform. Although more frequent use of behavioral escape avoidance coping is associated with lower risk appraisal, the converse is true for cognitive escape avoidance coping. Behavioral escape avoidance coping is unrelated to interpersonal skills (or scripts), but more frequent use of cognitive escape avoidance coping is significantly associated with lower levels of interpersonal sexual skills (See Figure 2B). There was no affect of adaptive coping on interpersonal sexual skills.

Risk appraisal, interpersonal factors, risk behavior

In the primary partners model interpersonal sexual skills and sexual scripts were not inter-related nor were they associated with high-risk sexual behavior. There was, however, a direct effect of CSA on sexual scripts with more severe abuse being significantly related to less aggressive scripts (See Figure 2B). In general, the primary partner model results suggest a clear CSA-Motivation-Coping-Risk Appraisal-Risk Behavior pathway.

Discussion

Partnership findings

The findings support substantial portions of the theoretical model, with important differences observed between secondary and primary partner models. In the present study, primary and secondary sexual relationships represent broad distinctions in types of close relationships. By definition, primary relationships involve a greater degree of commitment and love than secondary relationships (Peplau & Cochran, 1981; Shannon & Woods, 1991). Secondary sexual relationships encompass a more diverse range of sexual partnerships; although not a universal, they tend to be more transitory, and to involve more occurrences of high-risk sexual behavior (Buchanan, Poppen, & Reisen, 1996; Dudley, Rostosky, Korfhage, & Zimmerman, 2004; Dufour et al., 2000; Molitor, Facer, & Ruiz, 1999; Paul, Stall, Crosby, Barrett, & Midanik, 1994). MSM who engage in secondary sexual relationships often have large numbers of sexual partners which, in turn, will significantly impact HIV/STI spread in the population.

The findings point to two over-arching but inter-related pathways (e.g., both pathways include effects on interpersonal skills) linking CSA and high-risk behavior for men in secondary sexual relationships: 1) CSA-Motivation-Scripts-Skills-Risk Behavior, and 2) CSA-Motivation-Coping-Risk Appraisal-Skills-Risk Behavior. For men in primary relationships, there was only one over-arching pathway that includes CSA-Motivation-Coping-Risk Appraisal- Risk Behavior processes.

Why this difference in the primary versus secondary partner models? If sexual trauma potentially inhibits primary relationship formation, then we might suspect there is something different about men with CSA histories who are able to form primary vs. secondary relationships. Either their CSA history was less traumatic, or the sexual victimization was associated with other developmental experiences that enhanced emotional and psychological resilience (e.g., see Bonanno, 2004). For instance, they may have differential histories with respect to ameliorative or restorative relationships [e.g., supportive parent(s)]. Although we did not investigate restorative factors, we can examine for differences in functioning by relationship type through examination of men with CSA histories who reported only primary partners vs only secondary sexual partners. We conducted exploratory analyses at the level of observed variables ; these analyses, because of sample size, are limited to univariate statistics (t-/F-tests, Chi Square). We hypothesized that men in primary relationships, either because they had ameliorative experiences or less traumatic CSA experiences, would differ from men in secondary relationships in terms of having less interpersonal-anger, being less sexually preoccupied/compulsive, having lower depressive mood scores, reporting less use of escape avoidance coping and more use of adaptive coping, being more “other-directed,” having better interpersonal skills and less acceptance of violent behavior.

We limited this analysis to men with CSA histories who were only in primary (n = 57) vs. only in secondary (N = 105) sexual relationships in the past year to provide the most straightforward comparison for illustrative purposes. Although they did not differ on CSA severity (i.e., they had comparable sexual trauma histories based on the measures employed in this study), men in primary relationships were significantly less angry (on either anger scale; ps < .03), had lower depressive mood scores (p < .05), were less sexually preoccupied/compulsive (ps < .01) and more likely to be “other-directed” (p < .01). Men in primary versus secondary relationships were also less likely to be heavy drinkers (one index of behavioral escape avoidance), or use cognitive escape avoidance strategies (ps < .02; no significant differences in dissociation, denial, heavy drug use, or defensive avoidance were found). In terms of their sexual relationships, men in primary vs. secondary relationships had significantly more negative attitudes concerning the use of force in sexual relationships, and were better able to regulate sexual encounters towards positive outcomes for both themselves and their sexual partners (ps < .02). These findings suggest that men with CSA histories who are in primary relationships are socially and psychologically functioning better than those in exclusively secondary relationships. Analyses including men with CSA histories who had both primary and secondary sexual partners (n = 78) were similar to the prior results on key measures. In addition, men in primary relationships were significantly more likely to have used adaptive coping strategies for both instrumental and emotional issues (ps < .001). This result is consistent with the idea that men in primary relationships may have had a more extensive history of seeking and utilizing help for their CSA-related problems. Further, men with primary partners, regardless of the degree of sexual exclusivity in their relationships, have interpersonal characteristics and problem-solving oriented coping skills that may enhance the capacity to maintain intimate partnerships.

Motivation pathways: Affective motives

We examined four CSA-Motivation pathways: affective (depressive mood), interpersonal-affective (anger), interpersonal-approval seeking (”other-directedness”), and sexual motivations. The effects of CSA severity on affective motivation was robust across models, while CSA links to other motivational factors were less consistent. In both models, greater CSA severity was significantly associated with higher levels of affective distress (depressiveness), and greater affective distress (depressive mood) was, in turn, significantly related to more frequent use of behavioral and cognitive escape avoidance coping. This CSA-Affective(depression)-Coping pathway eventuates in high-risk sex in both secondary and primary partner models. The present findings support earlier work linking depression and high-risk behavior, and further suggests that prior inconsistencies in the literature linking affective conditions to high-risk sex may be due to not taking CSA histories and coping into account (see (O'Leary et al., 2003; Paul et al., 2001). Recently, Bancroft and Vukadinovic (Bancroft et al., 2003) found that adults with dysphoric mood (depression, anxiety) frequently had extreme problems controlling aspects of their sexual behavior (e.g., excessive cruising, excessive masturbation). They suggest an explanatory model involving affect-motivation, inhibition control, and self-regulatory failure that has parallels in our model of MSM with CSA histories.

Motivation pathways: Interpersonal-affective and affective motives

CSA severity was significantly related to interpersonal-affective motivation (interpersonal-anger) in the secondary partner model, but not the primary partner model. As noted previously, these findings may reflect the possibility that people with anger management problems have difficulty developing or maintaining intimate close relationships. Greater interpersonal-anger, in turn, was related to less frequent use of adaptive coping and greater use of cognitive escape avoidance coping strategies (but unrelated to behavioral escape avoidance coping). This CSA-Anger-Coping pathway eventuates in subsequent effects on risk appraisal, interpersonal sexual skills, and ultimately high-risk sexual behavior. Moreover, there is a significant pathway from interpersonal-affective motivation through sexual scripts to interpersonal sexual skills (see discussion of scripts and skills below) that also impacts high-risk sex. Thus, interpersonal-anger affects high-risk sex through multiple pathways involving coping and other interpersonal processes. Lastly, we note that, although there is not a significant CSA-interpersonal-affective pathway in the primary partner model, interpersonal-affective motivation (interpersonal-anger) is still an important consideration in primary relationships in that it affects coping mechanisms which, in turn, influence risk appraisals and high-risk sex.

Motivation pathways: Sexual motives

Sexual motivations were involved in nonsignificant CSA-pathways in both models. Our sexual motivation factor was composed of measures of sexual preoccupation and compulsivity. In a recent report, O’Leary et al., (2003) also found that CSA was unrelated to sexual compulsivity among MSMs. Preoccupation and compulsiveness are not, however, the only sexual motivations to consider. Bancroft et al. (2003) found that the ability to inhibit sexual arousal may affect engaging in high-risk sex. That is, it is not that men with a CSA history are necessarily more sexually compulsive or preoccupied than men without such histories, but they may have less control over their sexual reactions in harmful sexual situations. CSA experiences could facilitate this type of developmental response in adulthood since the child-victim is in fact unable to control either the sexual interaction or, at times, his own body’s physical responses to being sexually stimulated.

Motivation pathways: Social desirability motive

We examined the role of interpersonal-approval seeking, specifically “other-directedness,” as a mediator of the CSA-risk behavior relationship. Our construal of approval seeking in terms of “other- versus self-directedness” differentiates a personality characteristic, related to one’s orientation to the social world, from the methodological meaning of the motive. Highly “other-directed” persons may be more concerned about the desires of others than their own best interests (i.e., eager to please). Highly “inner-directed” persons may, alternatively, be more unconventional, and unconcerned about what others think, and therefore may have poor social skills relevant to developing good social relationships. The CSA literature indicates that a history of CSA may lead to being more “other-directed” (i.e., concerned about the opinions of others), and, therefore, less influenced by threats to self. However, we did not find this to be the case. In the primary partner model, CSA severity was unrelated to “directedness.” In contrast, there was a significant CSA-approval seeking pathway for men with secondary partners that included coping strategies, risk appraisal and, subsequently, high-risk behavior. The primary partner findings may reflect the possibility that men in primary relationships have greater mutuality in their relationships For men in secondary relationships, the results indicated, contrary to predictions, that men with greater CSA severity were more “inner-directed” (lower need for social approval). That is, CSA trauma may result for some men in a preoccupation with self to the exclusion of other’s feelings. When coupled with high levels of interpersonal anger, these conditions may elicit interpersonal problems that shorten relationships, and increase health risks by increasing the number of sexual partners.

Men who were more “inner directed” were also more sexually preoccupied/compulsive, were less frequent users of adaptive coping strategies, and more frequent users of cognitive escape avoidance coping. These findings are consistent with the interpretation that low need for approval scores indicate a self-preoccupation. For instance, men who are more self-absorbed may be less likely to use adaptive coping, which involves reaching out to others, and/or more likely to use internally oriented cognitive escape coping processes. Similarly sexual preoccupation/ compulsiveness may reflect self-absorption with sexual pleasure. We had hypothesized that in brief sexual encounters sexual motivations may have a stronger effect than interpersonal motivations on perceived risk. In longer-term relationships, wherein interpersonal goals of maintaining and enhancing the relationship may be more relevant, interpersonal motivations may be equal to or stronger than sexual motivations in influencing risk appraisals (Misovich et al., 1997). We did not find support for this hypothesis. However we did not specifically measure motives associated with maintaining and enhancing one’s relationship with the primary/secondary sexual partners; a subject for future study.

Coping pathways

The present work suggests a key, but complex role for coping strategies in the CSA-risk behavior models examined with respect to coping with affective, interpersonal-affective, and interpersonal-approval seeking motivations. Aside from predicted outcomes, the coping results revealed some unpredicted effects. In the secondary partner model, greater CSA severity was directly associated with less frequent use of behavioral escape avoidance coping. One explanation for this finding is that some men with severe CSA trauma are able to cope more frequently and/or successfully with cognitive strategies with less reliance on behavioral escape avoidance coping. This may be an outcome of the CSA trauma or a consequence of ameliorative factors. Victims of sexual abuse are typically placed by the perpetrator in a situation in which they are less able to physically do anything about the abuse, and, therefore, may rely more on cognitive coping strategies to escape. Therapy directed at reducing self-destructive behaviors, for instance, may also reduce behavioral escape avoidance coping. As noted, we do not have data on therapeutic histories. Finding that more frequent use of cognitive escape avoidance coping was associated with greater fear of HIV was unexpected. In some instances, this finding may be indicative of “corrective hindsight.” That is, one engages in a high risk activity partly because one is contemporaneously engaging in escape avoidance coping, but later (such as at the time of interview) one re-categorizes the behavior as high risk (“from a safe distance?). This result, however, may also reflect the effects of other coping strategies or motivational forces not assessed in the present study (e.g., spiritual coping, coping × anger interactions).

Interpersonal pathways

Sexual scripts, as discussed here, represent learned patterns of sexual interaction that guide sexual relationships and affect sexual pleasure. Although the scant literature on these topics suggests that either highly aggressive or passive scripts might develop from CSA histories, the present results indicated that it was the more aggressive sexual script that was associated with problematic behaviors. Sexual scripts were part of a significant CSA-Motivational pathway that influenced sexual skills; more aggressive scripts were significantly related to poorer interpersonal sexual skills. This result may reflect the fact that the measures of interpersonal skills assessed here imply a level of caring or nurturing that may be absent when one is following an aggressive sexual script. Sexual aggression does not lead to mutuality in sexual outcomes unless one’s partner is masochistic. More aggressive scripts were found to be influenced by higher levels of interpersonal-anger. CSA driven interpersonal-anger may lead to the development of aggressive scripts as a means of satisfying both one’s sexual needs and expressing anger towards the original perpetrator (symbolically speaking).

Sexual skills are essential to healthy sexual outcomes in most models of sexual health behavior. With respect to CSA trauma, however, the import of sexual skills to risk behavior was primarily relevant in the secondary sexual partner relationship. This may reflect the higher functioning of men in primary relationships. It may also reflect the possibility that in primary relationships, where mutuality is high, the simple desire to protect one another from harm may be sufficient to achieve healthy goals without assertiveness and communication skills being necessary. In secondary relationships, mutuality and nurturance may be lower, and therefore, something more is needed to ensure harm reduction. In the secondary sexual partner model, interpersonal sexual skills directly impact, independent of risk appraisals, high-risk sexual behavior; lower skills are related to higher risk sexual activity. Interpersonal skills are influenced by CSA severity via interpersonal-anger and sexual script pathways (greater anger and more aggressive scripts are associated with poorer skills). Coping and risk appraisals also impact sexual skills. More frequent use of adaptive coping and less use of cognitive escape avoidance coping are associated with better skills, and higher levels of risk appraisal stimulate better skill performance. These results are theoretically consistent and underscore the role of emotional and cognitive processes in facilitating healthy sexual behavior via enhanced skill development.

Risk appraisal pathways

Risk appraisals have a direct impact on risk behavior in both models (and an indirect effect in the secondary partner model via skills), and as expected, such appraisals are influenced by coping processes (as discussed previously). Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, and as pointed out by Weinstein and Nicoloch (1993), we were somewhat fortunate to have found a theoretically consistent relationship between risk appraisals and risk behavior (lower concern associated with greater risk behavior). Because of the reciprocal nature of this relationship one could also observe the opposite relationship in a cross-sectional study. The obtained result is more often found in populations in the early stages of an epidemic, which is consistent with the observation that MSM are entering a new epidemic phase facilitated paradoxically, in part, by better treatments (Huebner et al., 2004). The current findings suggest that risk appraisals play a key role in the CSA trauma model and future work should focus on factors that may assist men with a history of sexual trauma in making accurate appraisals.

Because motivational and coping factors are key mediating components of CSA and high-risk sexual behavior, and their effects are further mediated through interpersonal processes (scripts, interpersonal sexual skills), then we conclude that prevention strategies focusing exclusively on skill building may more often fail for MSM with more severe CSA histories. Indeed, most HIV relevant cognitive-behavioral prevention programs tend to focus on sexual skills and situation specific elements within the sexual interaction.

Indeed CSA poses considerable challenge for HIV prevention. As Briere (2004) has pointed out, treatment for CSA-related problems may not be an effective way of preventing HIV risk in the general population. However, there may be many MSM CSA survivors currently in therapy that may be helped with reducing their HIV risk by addressing HIV-relevant risk factors, such as those described herein (e.g., cognitive-behavioral treatments for improving coping strategies, affect regulation, and interpersonal skills; substance abuse interventions) (e.g., Briere, 2004; Chin, Wyatt, Vargas Carmona, Burns Loeb, & Myers, 2004). Further, our results suggest that sexual histories may be useful as markers for identifying MSM CSA-survivors with more wide ranging problems (i.e,. men with secondary sexual partners to the exclusion of primary relationships). Moreover, the success of short-term HIV prevention programs may be increased by focusing on MSM CSA survivors in primary relationships. In addition, increased attention may be given through secondary education efforts directed at evaluating and augmenting therapist skills in addressing the sexual relationships of MSM CSA patients. We would note, however, that men with poor histories of seeking help from others may be less inclined to sustain therapeutic contact even if initiated. Paul et al., (2001) have recommended case-management approaches to help facilitate sustained therapeutic contact. Aside from men in therapy, broader population-approachs may include developing public health campaigns that help normalize disclosure of CSA histories and facilitate treatment seeking. Similar “destigmatizing campaigns” have been made with respect to AIDS and other stigmatized health conditions (e.g., erectile dysfunctions).

Study limitations

We limited our analysis in several ways. First, we do not include previously studied personality, cognitive, and social factors that may influence the antecedents or outcomes of risk appraisal or enactment (e.g., self-efficacy beliefs; HIV knowledge; perceived health cues; social networks; other life-stresses). Many of these variables either have hypothesized pathways that are already represented by variables we examined, or have pathways that may not be relevant to a history of CSA. Furthermore, the small number of men in any one ethnic minority group in our study prohibits detailed analyses of subculture issues. Despite these limitations, the empirical model we examined includes key mediators of CSA and HIV sexual risk behavior that may be amenable to intervention efforts.

As with all research based on retrospective assessments of developmental events, recall error is a common concern. However, a number of studies have found that many CSA victims have reasonably reliable recall of their CSA experiences, and that retrospective assessments of CSA characteristics have consistent and reliable relationships to adult outcomes of relevance to research on HIV sexual risk behavior (Jinich et al., 1998; Johnsen & Harlow, 1996; Loferski et al., 1992; Paul et al., 2001; Whitmire et al., 1999). An additional challenge is one of statistical power. Even though CSA is a highly prevalent developmental trauma among MSM, one needs large sample sizes to test the types of models examined in the current investigation. In this regard, we did not have sufficient power to model distinct partnership groups beyond secondary and primary partnership models. Men with both primary and secondary partners appear from our univariate analyses to be somewhere between men with only primary partners and those with only secondary partners with respect to many of the independent variables. As such, we included this group in both models for purposes of analysis, therefore the differences between models may be more extreme than represented here. Further, our theoretical work has not evolved sufficiently to predict what key interactions should be examined beyond relationship type (i.e., an interaction is inferred in our strategy of breaking analyses into two relationship models).

Future considerations

For practical reasons the factors in the present study have limited representation. For instance, the affective factor does not include assessments of anxiety. Anxiety, like depression, may have differential relationships to risk appraisals and enactment of safe sex (e.g., see Bancroft, Janssen, Strong & Vukadinovic, 2003). For instance, Miller (1999) has observed that post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) may contribute to a decrease in risk behavior. That is, PTSD may motivate hyper-vigilance that enhances appraisals of risk and, consequently, avoidance of sexual situations because they all “appear” dangerous. In addition, the role of affective motives in high-risk sex may be more complex than the current model illustrates. For instance, severe depression may reduce motivation for seeking sex. Future work should explore the influence of more severe mental health problems among CSA victims in relation to sexual health risks. Guilt (e.g., survivor guilt), jealousy, and other relationship/sex relevant emotions would also be logical candidates for study. Other avenues for investigation with respect to the sexual motivation factor and social desirability factor have been discussed. The role of adaptive coping could be expanded to encompass the broader set of considerations associated with social support (e.g., network limitations). In addition, help-seeking and professional care experiences would, from our prior discussion, be relevant areas for future study.

Summary

Models were tested that explored potential mediators of CSA and adult sexual health, notably HIV/STI related risk behaviors. The secondary sexual partners model was the most complex with multiple pathways leading from CSA to high-risk sex. The primary sexual partners model was less complex with only one significant over-arching pathway observed linking CSA to high-risk sex. Explanations for these differences by partnership type are discussed and detailed discussion of specific pathways is provided.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grant MH054320. Consulting to this project were Dr. David Finkelhor, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, and Dr. Kathleen Kendall-Tackett and Dr. Diana Elliott, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bancroft J, Janssen E, Strong D, Carnes L, Vukadinovic Z, Long JS. Sexual risk-taking in gay men: The relevance of sexual arousability, mood and sensation seeking. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:555–572. doi: 10.1023/a:1026041628364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Williams LM. Characteristics of child sexual abuse as correlates of women's adjustment: A prospective study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:853–865. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fix indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binson D, Moskowitz JT, Mills TC, Anderson K, Paul JP, Stall R, Catania J. Sampling men who have sex with men: Strategies for a telephone survey in urban areas in the United States. Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods. American Statistical Association. 1996;1:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 2004;59(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Integrating HIV/AIDS prevention activities into psychotherapy for child sexual abuse survivors. In: Koenig LJ, O'Leary A, Pequegnat W, editors. From child sexual abuse to adult sexual risk: Trauma, revictimization, and intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Elliott D, Harris K, Cotman K. Trauma symp[tom inventory: Psychometrics and assoication with childhood and adult victimization in a clinical sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;4:151–163. Trauma Symptom Inventory www.nnfr.org/eval/bib_ins/BRIERE.html. [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99(1):66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan DR, Poppen PJ, Reisen CA. The nature of partner relationship and AIDS sexual risk-taking in gay men. Psychology and Health. 1996;11:541–555. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM. Sexual abuse and maladjustment considered from the perspective of normal developmental processes. In: O'Donohue W, Geer JH, editors. The sexual abuse of children: Theory and research. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Dieguez A, Dolezal C. Association between history of childhood sexual abuse and adult HIV-risk sexual behavior in Puerto Rican men who have sex with men. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19(5):595–605. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D. Problem drinkers: A national survey. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Binson D, Dolcini MM, Moskowitz JT, van der Straten A. Frontiers in the behavioral epidemiology of HIV/STDs. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 777–799. [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Canchola JA, Pollack LM, Chang J. Understanding survey sample demographic characteristics of men who have sex with men. American Statistical Association Proceedings. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Coates TJ, Kegeles S. A test of the AIDS Risk Reduction Model: Psychosocial correlates of condom use in the AMEN Cohort Survey. Health Psychology. 1994;13(6):548–555. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: An AIDS risk reduction model (ARRM) Health Education Quarterly. 1990;17(1):53–72. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, McDermott L, Wood J. Assessment of locus of control: Situational specificity in the sexual context. Journal of Sex Research. 1984;20:310–324. [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Morin SF, Canchola J, Pollack L, Chang J, Coates TJ. U.S. priorities-HIV prevention. Science. 2000;290:717. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Osmond D, Neilands T, Canchola JA, Gregorich S, Shiboski S. Commentary on Schroder et al., (2003a; 2003b) Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29(2):86–95. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Osmond D, Stall RD, Pollack L, Paul JP, Blower S, Binson D, Canchola J, Mills T, Fisher L, Choi K-H, Porco T, Turner C, Blair J, Henne J, Bye L, Coates T. The continuing HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men: a comparison of those living in "gay ghettos" with those living elsewhere. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):907–914. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Paul J. Sexual development and mental health among men who have sex with men; Paper presented at the NIH Conference: New approaches to research on sexual orientation, mental health, and substance abuse; Bethesda, MD. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chin D, Wyatt GE, Vargas Carmona J, Burns Loeb T, Myers HF. Child sexual abuse and HIV: An integrative risk-reduction approach. In: Koenig LJ, O'Leary A, Pequegnat W, editors. From child sexual abuse to adult sexual risk: Trauma, revictimization, and intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- de Vroome EMM, de Wit JBE, Stroebe W, Sandfort TGM. Sexual behavior and depression among HIV-positive gay men. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2(2):137–149. [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Hartwell T, Hansen N. Childhood sexual abuse and risk behaviors among men at high risk for HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(2):214–219. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley MG, Rostosky SS, Korfhage BA, Zimmerman RS. Correlates of high-risk sexual behavior among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Preventnion. 2004;16(4):328–340. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.328.40397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A, Alary M, Otis J, Noel R, Remis RS, Masse B, Parent R, Turmel B, Lavoie R, LeClerc R, Vincelette J. Correlates of risky behaviors among young and older men having sexual relations with men in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Omega Study Group. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2000;23(3):272–278. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200003010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner TM, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Ehrhardt AA. Sexual self control as a mediator of high risk sexual behavior in a New York City cohort of HIV+ and HIV-gay men. The Journal of Sex Research. 1992;29(3):389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Current information on the scope and nature of child sexual abuse. The Future of Children. 1994;4(2):31–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55(4):530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Moore D, Hamby SL, Straus MA. Sexually abused children in a national survey of parents: Methodological issues. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Fisher W. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–674. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1988a. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Social Science & Medicine. 1988b;26(3):309–317. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L, Stepanski EJ. A step-by-step approach to using the SAS System for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Preston L. Individual differences in the experience of sexual motivation: Theory and measurement of dispositional sexual motives. The Journal of Sex Research. 1996;33(1):27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hoier TS, Shawchuck CR, Pallotta GM, Freeman T, Inderbitzen-Pisaruk H, MacMillan VM, Malinosky-Rummel R, Greene AL. The impact of sexual abuse: A cognitive-behavioral model. In: O'Donohue W, Geer JH, editors. The sexual abuse of children: Clinical issues. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 100–142. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. A longitudinal study of the association between treatment optimism and sexual risk behavior in young adult gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2004;37(4):1514–1519. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000127027.55052.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinich S, Paul JP, Stall R, Acree M, Kegeles S, Hoff C, Coates T. Childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk-taking behavior among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2(1):41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen LW, Harlow LL. Childhood sexual abuse linked with adult substance use, victimization, and AIDS-risk. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8(1):44–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Benotsch E, Rompa D, Gore-Felton C, Austin J, Luke W, DiFonzo K, Kyomugisha F, Simpson D. Unwanted sexual experiences and sexual risks in gay and bisexual men: Associations among revictimization, substance use and psychiatric symptoms. Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick AC. Long-range effects of child and adolescent sexual experiences: Myths, mores, and menaces. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Mathtech questionnaires: Sexuality questionnaires for adolescents. In: Davis C, Yarber W, Bauserman R, Schreer G, Davis S, editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. Factors related to HIV risk: Predictors of risky sexual behavior and attitudes toward microbicide use. University of Rhode Island; 1998. Unpublished Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Lipovsky JA, Kilpatrick DG. The child sexual abuse victim as an adult. In: O'Donohue W, Geer JH, editors. The sexual abuse of children: Clinical issues. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 430–476. [Google Scholar]

- Loferski S, Quina K, Harlow LL, Morokoff PJ. Will the pain ever stop? Abuse and AIDS in women; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Women in Psychology; Long Beach, CA. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Bingman CR, Duval TS. Negative affect and unsafe sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2(2):89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A model to explain the relationship between sexual abuse and HIV risk among women. AIDS Care. 1999;11(1):3–20. doi: 10.1080/09540129948162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misovich SJ, Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Close relationships and elevated HIV risk behavior: Evidence and possible underlying psychological processes. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1(1):72–107. [Google Scholar]

- Molitor F, Facer M, Ruiz JD. Safer sex communication and unsafe sexual behavior among young men who have sex with men in California. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1999;28(4):335–343. doi: 10.1023/a:1018748729070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus user's guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen and Muthen, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]