Abstract

Despite evidence of considerable racial/ethnic variation in adolescent suicidal behavior in the United States, research on youth of European American descent accounts for much of what is know about preventing adolescent suicide. In response to the need to advance research on the phenomenology and prevention of suicidal behavior among ethnic minority populations, NIMH co-sponsored the “Pragmatic Considerations of Culture in Preventing Suicide” workshop to elicit through interdisciplinary dialogue how culture can be considered in the design, development, and implementation of suicidal behavior prevention programs. In this discussion paper we consider the three ethnic minority suicide prevention efforts described in the articles appearing in this issue, along with workshop participants’ comments, and propose six major areas where issues of culture need to be better integrated into suicidal behavior research.

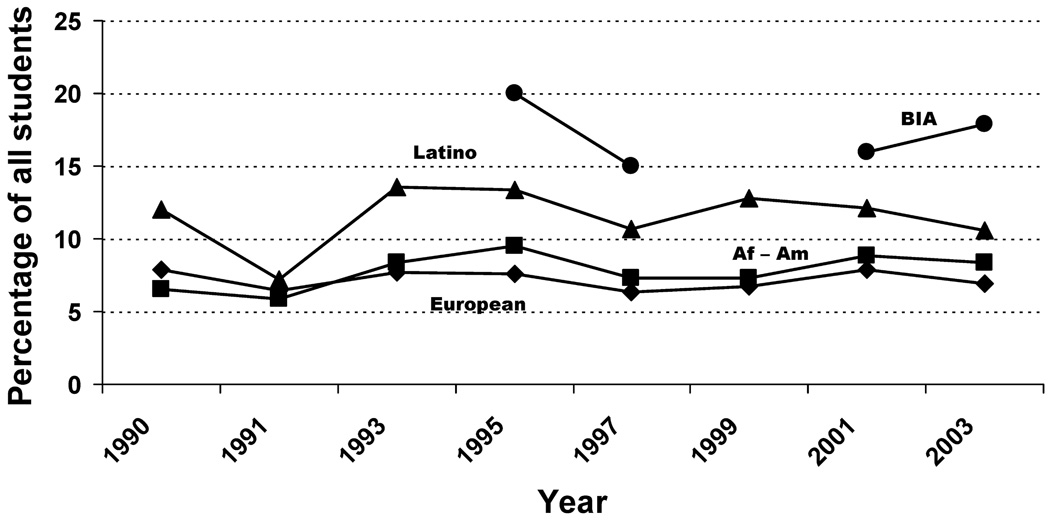

In the United States, there is significant variability in suicidal ideation and behaviors among adolescents of different ethnic back-grounds. In adolescent populations, American Indian/Alaska Native youth tend to have highest rates of ideation and nonfatal suicidal behavior of all ethnic groups, followed by Latina/o and then African American and European American youth (see Figure 1). Across ethnicities, nonfatal suicidal behavior is more common in girls than in boys, by an average ratio of 3:1. At the same time, the gender gap in rates of nonfatal suicidal behavior is most pronounced among youths of European American descent, and least pronounced among some American Indian youths (Canetto, 1997). For example, among Native Hawaiians and some American Indians (i.e., among Pueblo Indians but not Zuni Indians), adolescent males report similar rates of nonfatal suicidal behavior as adolescent females (Howard-Pitney, LaFromboise, Basil, September, & Johnson, 1992; Joe & Marcus, 2003; Yuen et al., 1996). American Indian youth have historically recorded the highest rates of suicide mortality, though there are significant variations in suicide mortality rates across tribes.

Figure 1.

Percentage of high school students who report suicidal behavior* by ethnicity, 1990–2003

*At least one attempt during the 12 months preceding the survey; European and African American youth do not include Latinos.

Source. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) & Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) YRBSS.

Across ethnicities, suicide is more common among boys than among girls, by an average ratio of 5:1 (Canetto & Lester, 1995). In recent decades, the gender gap in suicide mortality has been widening, especially in some U.S. ethnic minority groups (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1998, 2004; Joe & Marcus, 2003; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMSHA], 2003). The widening gender gap is mostly due to increased suicide rates for ethnic minority boys since rates of suicide mortality among girls of all ethnic groups have remained stable. Historically, European American youths had higher rates of suicide than African American youths. In recent decades, however, suicide rates for African American male adolescents have increased more rapidly than suicide rates for European American male adolescents, such that the gap between the rates for these two groups is now narrower. The increase in African American male youth suicide has been particularly substantial in the South (CDC, 1998).

Longitudinal studies indicate that the variability in suicidal behaviors across ethnicities has become less pronounced in the last 20 years (Goldsmith, Pellmar, Kleinman, & Bunney, 2002; Mohler & Earls, 2001; Thompson, 2004); for example, rates of suicide among Hispanic and African American youths have become increasingly similar to those of European American youths (CDC, 1998, 2004; Joe & Marcus, 2003; SAMSHA, 2003). The “gender paradox” of suicidal behavior, however, persists (Canetto, 1997; Canetto & Lester, 1998), where males have higher suicide mortality and females have higher nonfatal suicidal behavior.

In addition to gender and ethnicity, other factors appear to be associated with risk for suicidal behavior among adolescents. One important such factor is sexual orientation. Young persons who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual are twice as likely as their hetero-sexual peers to have a history of suicidal behavior (Russell & Joyner, 2001). High rates of nonfatal suicidal behavior have been especially well-documented among gay males (McDaniel, Purcell, & D’Augelli, 2001). An other factor is social class. Adolescents who engage in nonfatal suicidal behavior tend to be from lower socioeconomic strata, and low levels of parental education are associated with higher adolescent suicidal risk (Canetto, 1997).

Despite evidence of considerable ethnic variation in adolescent suicidal behavior, research has focused on youth of European American descent. This research has identified potential suicidal behavior risk factors for this population (Beautrais, 2003). Risk factors include a history of mental disorders, physical illness and functional impairment, and cultural permissibility; psychological and physical access to immediately lethal methods; and exposure to suicidal behavior (including a family history of suicidal behavior, recent suicidal behavior by a friend, and a person’s own past suicidal episodes). Stressful life events, including turmoil and instability in important relationships, particularly in the parent-child relationship, appear to be precipitants of suicidal behavior in adolescents (Canetto, 1997; Evans, Hawton, & Rodham, 2004). However, the high or increasing rates of suicidal behavior of some ethnic minority adolescents, particularly ethnic minority boys, remain relatively unexplored.

A key issue in adolescent suicidal behavior is that risk factors often impact boys and girls differently. On the one hand, similar risk factors are associated with different suicidal behaviors in boys and girls, specifically fatal suicidal behavior in boys and nonfatal suicidal behavior in girls. Relative to girls, boys seem protected from suicidal ideation and nonfatal suicidal behavior but more vulnerable to suicide mortality. On the other hand, different factors are sometimes associated with suicidal behavior in girls and boys. For example, mental disorders, depression, alcohol and substance abuse, and conduct disorders are most commonly associated with risk for suicidal ideation and behavior, both fatal and nonfatal, among European American adolescents. However, for European American girls, depression appears to be a better predictor of suicidal behavior than for boys, while alcohol and substance abuse and conduct disorders appear to be stronger correlates of suicidal behavior for European American boys than for girls. In recent years in the United States, sexual abuse is increasingly being recognized as a factor in girls’ nonfatal suicidal behavior. Also, conflict with parents seems to create a unique vulnerability for girls’ nonfatal suicidal behavior (Canetto, 1997).

In response to the need to advance research on the phenomenology and prevention of suicidal behavior among ethnic minority populations, NIMH co-sponsored the “Pragmatic Considerations of Culture in Preventing Suicide” workshop (see Shropshire et al., this issue). The purpose of this meeting was to explore how culture can be considered in the design, development, and implementation of suicidal behavior prevention programs. The workshop featured three promising suicide prevention research projects focused on three U. S. ethnic minority populations (African Americans, Latinas, and Native Americans) as a means for eliciting new understanding of the association between culture, ethnicity, and suicidal behavior.

In this discussion paper we consider the three suicide prevention efforts described in the articles appearing in this issue (see Molock et al.; LaFrombroise & Lewis; and Zayas & Morales), along with workshop participants’ comments, and propose future directions for suicidal behavior research. Specifically, we propose six major areas where issues of culture need to be better integrated: theories of suicidal behavior, the phenomenology of suicidal behavior, population-level research, research design, suicide stigma, and cultural mistrust.

CULTURE AND THEORIES OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR

While there is an abundance of empirical studies on suicidal behavior, suicidal behavior research is not adequately inspired by theory (Joiner, 2005). Suicide research is more often guided by hypotheses regarding risk or protective factors than by theoretical frameworks. Arguably the fact that we are still debating the definition of suicidal behaviors has limited the advancement and application of behavioral theory in the prevention of suicidal behaviors (see O’Carroll et al., 1996). Suicide prevention researchers are also at a disadvantage because of the often atheoretical nature of intervention development in the field. An examination of the three case studies in this special section research veals that it would be difficult to determine what works, given the variance across the three models regarding the intervention components and risk factors targeted. Similarly, a comprehensive review by experts from 15 countries of the evidence for the effects of suicide prevention interventions contends that heterogeneity in study methods, including the multifaceted nature of intervention programs, limits the ability to draw conclusions regarding what works and why (Mann et al., 2005).

Suicide prevention can be a part of more general health promotion efforts. As such, it is most likely to benefit participants and communities when it is guided by social, psychological, and behavioral science theories of health behavior and health behavioral change. Suicide prevention science must be grounded in robust theoretical frameworks that provide testable hypotheses. As evidenced by the findings of a recent review (Mann et al., 2005), without good theory, it is difficult to determine which components produce the desired outcome. Herein lays a great opportunity to advance suicide prevention research—through the development of theory. This would provide a richer investigative context in which to parse the effects that culture, ethnicity, and social class have on suicide risk. More importantly, it would provide a common framework for examining population-specific and potentially modifiable risk factors that could be targeted in suicide interventions for a diversity of populations. If the complex nature of suicidal behaviors proves too difficult to be bounded by one theoretical perspective, the applicability of well-established behavioral theories used for testing the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions for other health risk behaviors should at least be explored for their relevance to suicide prevention research.

The role of theory in guiding interventions is relevant to interpreting the different intervention strategies used in the three case studies in this issue. Although each team focused on a different mode of intervention (church, family therapy, and schools), it is not clear if these modes were selected merely to enhance their ability to reach youth most at risk or whether they carry special significance as places that are culturally congruent with intervention goals. Good theory would help us to understand the cultural significance of these sites and why they provide a good point of intervention for the prevention of suicidal behaviors.

The future design of suicidal behavior prevention programs will continue to benefit from the theoretical and technical insights generated by other morbidity/mortality prevention and health promotion theories and programs, such as substance abuse prevention programs or violence prevention programs. At the same time, to make progress, suicide prevention science and research must also foster its own theoretical development, and generate suicidal behavior specific hypotheses. One opportunity created by the slow theoretical development of theory in the area of suicidal behavior is that suicidal behavior theory could address and integrate from the start issues of diversity, including gender, culture, sexual orientation, and social class.

CULTURE AND THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR

Research is needed to understand the phenomenology of suicidal behaviors among ethnic minority populations (Goldsmith et al., 2002). This includes research on the presentation of ethnic minority suicidal behavior, meanings of suicidal behavior in different cultural groups, risk factors for suicidal behaviors and their correlates, and mechanisms that may serve to deter suicidality. This is not to suggest that many of the known suicide risk factors are not applicable to ethnic minority populations. Rather, research should confirm these associations, their strengths, and whether the presentation of known suicide risk factors (e.g., depression) may apply to ethnic minority populations. We need to advance research in this area. This knowledge will help to identify potentially modifiable risk or protective factors that can be the target of preventative interventions (see Zayas & Morales, this issue).

In the United States culture is often considered synonymous with the experience of ethnic minorities. By contrast, the culture of the dominant group is often invisible to dominant culture researchers, who view themselves, and European American research participants, as generic individuals rather than ethnic individuals. This attitude often translates into over-attributions to culture in the case of ethnic minorities, and underestimating the role of culture with regard to is-sues involving the dominant ethnic group (Canetto & Lester, 1998). Because ethnic minorities tend to cluster at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder, researchers also tend to confuse the effects of ethnicity with the effects of socioeconomic status. Hence, an important area of future investigation is to disentangle the role of culture from that of socioeconomic status.

Furthermore, given the stigma associated with suicide, particularly for ethnic minorities, and African Americans in particular, priority should be given to qualitative ethno-graphic studies. Ethnographic methods may be more effective for traversing the complex experiences of ethnic minorities and can provide greater understanding of what may have caused recent changes in suicidal behavior. They may also be more apt to monitoring interacting variables in context. Finally, ethnographic methods may be more culturally congruent with the preferred modes of communication and may consider different methods with different ethnic groups. There is also the potential to advance scientific knowledge and add much to the understanding of the relative roles of ethnicity, culture, socio-economic, and other factors as risk and protective factors for suicidal behaviors.

In addition, future research is needed to further our understanding of the role of predisposing, precipitating, protective, and contributing factors including:

the roles of racism, segregation neighborhood influences, and other forms of discrimination

socioeconomic factors (such as extreme poverty and limited economic opportunities)

the effects of acculturation and potential erosion of protective ethnic specific social support systems and resources

variability in family and social network patterns among ethnic groups

the role of faith/spirituality

cultural issues associated with specific geographic communities

sexual orientation issues

CULTURE AND POPULATION-LEVEL RESEARCH

Theoretically or empirically driven hypotheses are needed to explain changes in the patterns of suicidal behaviors among ethnic minority populations. For instance, why were previous generations of Blacks able to endure centuries of epic cruelty, while managing to avoid succumbing to hopelessness and depression, whereas recent generations experience higher rates of suicide, especially among the young? To answer this question would require making an important distinction between research on individual suicide risk from investigations that explore historical and population-level changes in the patterns of suicidal beliefs and behavior (Joe, 2006). Although these two investigative tracks are arguably linked, in the rush for explanations for the unprecedented changes in the patterns of suicidal behavior among ethnic minorities, we must be careful not to fallaciously interpret the research results from individual risk studies as explanations for macro level changes, for example, in the patterns of African American suicide. A failure to make this distinction between factors related to population-level changes and those related individual-level risk could at minimum result in inappropriate use of resources, or at worst, cause iatrogenic outcomes.

Population-level studies often require an historical/temporal analytic perspective in order to identify factors associated with alterations in an ethnic minority group’s perpetuating and precipitating factors related to suicidal behavior. It is plausible to consider that the factors related to suicidal behavior are similar across all ethnic groups and eventually result in comparable levels of vulnerability across populations. This perspective implies that all groups’ exposure to and interpretation of similar historical changes might result in them experiencing similar rates of suicidal behaviors. Research on population-level factors would include a focus on the role of acculturation, including adoption of a new language, experience of historical trauma, the effects of colonization, and the need for longitudinal population-level data (Joe, 2006). The focus on population-level analysis should not suggest that individual analysis could not generate population-level hypotheses. Nevertheless, in order for individual-level investigations of the correlates of suicidal behavior to be used to understand population-level changes, research should be designed to confirm the relationships between changes in population-level factors presumed to be related to a group’s suicide. Insight from such studies would greatly inform suicide prevention strategies, particularly for ethnic minority populations.

CULTURE AND RESEARCH DESIGN

The design of preventative intervention research must be responsive to cultural and social context. Culture powerfully shapes and constrains the nature of the interactions and relationships between the delivery of the intervention and treatment seeking. Culture is a product of people living together and creating traditions, norms, and values that manifest as a pattern in a specific group of people (Bille-Brahe, 2000). It is therefore essential to consider the culture of the target population as researchers make decisions regarding the intervention strategy and curriculum, selection of measures, intervention length and setting, and manner of delivery of the intervention or service. Culture, however, is not and should not be used as a synonym for race. Race in the American context is not about an individual’s skin color, normative beliefs or behaviors. Rather race refers to the nature of an individual’s relationship to other people within the society (Zuberi, 2001). When investigators make slight of this point or purposefully confound race and culture, research on the role of culture becomes the justification for racial stratification and distorts our understanding of casual pathways.

Culture is related to what research participants bring to the intervention research experience. Therefore, prevention researchers should consider the relevance of cultural values, customs, and strengths within specific domains, such as work, school, relationships, and therapy (Santiago-Rivera, 1995), when designing preventative interventions. Molock and colleagues (this issue), making a similar point, contend that the cultural relevance of African Americans coping strategies is an integral part of their decision to involve the Black Church in suicide prevention. For African Americans, social support and spirituality are posited to be particularly relevant coping resources in the African American culture (Billingsley, 1992; Thomas, 2001). In fact, they have been found to be preferred ways to deal with adversity in the African American community (Boyd-Franklin, 1991; Mattis, 2000; Taylor, Hardison, & Chatters, 1996) compared to formal services. Mental health professionals have historically neglected social support and spirituality as culturally relevant factors in clients’ ability to cope with psychosocial problems. Similar arguments could be made for considering culturally relevant factors when designing suicide prevention strategies for Latina/o and American Indian populations. These are but a few ways culture could be considered when designing suicide prevention research projects.

CULTURE, SUICIDE STIGMA, AND THE PREVENTION OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIORS

An Institute of Medicine report identified suicide stigma as an important barrier to preventing suicide (Goldsmith et al., 2002). Given the importance of attitudes in directing health behaviors, research on stigma surrounding suicide is needed to understand its significant clinical and prevention implications. Suicide stigma impacts the collection and accuracy of suicide mortality data, because the process for making an official ruling on the manner of death is open to influence from the families’ and others who act on the behalf of families seeking to reduce the potential shame such a designation would bring (Goldsmith et al., 2002; Manderscheid et al., 2004). Suicide stigma also directly impacts suicidal persons and their families (Manderscheid et al., 2004; U.S. Public Health Service, 2001). When confronted with suicidal behavior, many families suffer in isolation from pain and grief associated with the stigma (Manderscheid et al., 2004; U.S. Public Health Service, 2001). LaFrombroise and Lewis (this issue) and Zayas and Morales (this issue) make note of how stigma can be an impediment to participatory research and to conducting intervention research with long-term follow-up.

Because suicidal behavior remains a stigmatized public health concern, it is important to understand how society as well as subcultures view suicidal behavior (Joe, Romer, & Jamieson, 2007; Stillion & Stillion, 1998). Research is needed to understand the mechanisms and pathways through which suicide stigma acts as both a protective and risk factor for both males and females. To date, research suggests an interesting paradox that, on the one hand, stigma appears to prevent suicidal behavior (Early, 1992; Early & Akers, 1993) and, on the other hand, it interferes with help-seeking behavior by suicidal individuals and significant others (Goldsmith et al., 2002; Taylor-Gibbs, 1997). LaFrambroise and Lewis as well as Zayas and Morales make note of how stigma interfered with participation in and/or with sustaining the long-term success of a suicide prevention program. Despite the recent Institute of Medicine report that identified the paucity of research on the stigma of suicide as an important barrier to suicide prevention, no prevention study has focused on reducing the stigma of suicide or examined systematically whether it should be a part of suicide prevention strategies, particularly for ethnic minority populations.

CULTURAL MISTRUST

Cultural mistrust must be considered when designing suicide prevention initiatives for ethnic minority populations (Poussaint & Alexander, 2000). Cultural mistrust is an attitudinal response to historical trauma, such as years of racial and economic oppression. An attitude of mistrust negatively affects some ethnic minorities’ interactions with members and institutions of the dominant culture (Terrell, Terrell, & Miller, 1993). A case in point, African Americans with high levels of cultural mistrust will expect that members or institutions of the dominant culture will not treat them in a fair manner (Ogbu, 1991). There are several decades of research in the clinical and counseling area on cultural mistrust, dating back to the introduction of the construct of “healthy cultural paranoia” (Grier & Cobbs, 1968). Clinical research has typically addressed the relationship between cultural mistrust and attitudes toward mental health services. These studies suggest that African Americans who are high in cultural mistrust tend to have more negative attitudes toward therapy delivered by European American clinicians and greater expectations of bias from the mental health system (Phelps, Taylor, & Gerard, 2001; Whaley, 2001, 2002).

The implications of cultural mistrust for U.S. suicide prevention efforts are considerable and warrant further investigation. Cultural mistrust could impact several aspects of the prevention research process, including the ability to gain community support, particularly for American Indians (LaFrambroise and Lewis, this issue), as well as participant recruitment, retention, and the sustainability of the interventions. To address such concerns, some researchers have sought to include ethnic minority facilitators and trainers for their projects; however, the evidence for the effectiveness of these approaches is still unclear. More research is needed to determine how cultural mistrust impacts the design and efficacy of suicide prevention strategies for ethnic minority groups. In addition, the development of a stronger research training infrastructure to support and encourage ethnic minority investigators, particularly junior faculty, from the target communities who are capable of conducting randomized clinical trails must be a part of the strategy to advance suicide prevention science. Greater ethnic minority rep-resentation in the fields of suicidology will stimulate the development of more culturally specific hypotheses and approaches likely leading to more effective preventive interventions.

CONCLUSION

The oral and written contributions generated by the NIMH co-sponsored work-shop on “Pragmatic Considerations of Culture in Preventing Suicide” have stimulated important questions on the topic. Most importantly, they have suggested new issues and directions for research and the practice of suicidal behavior prevention. If there is one conclusion generated by these contributions it is that advancing our understanding of cultural issues in suicidal behavior is critical to increasing our ability to prevent suicidal behavior in all groups in a diverse society. Culture is not simply an issue about and for ethnic minorities. It is about and for everyone. Also, a focus on culture reinforces the importance of examining suicide risk and resilience in context. Finally, a focus on culture clarifies that one cannot consider cultural influences as separate from the influence of other social factors, including gender ideologies, generational experiences, and socioeconomic status. As we continue to understand how culture influences suicidal behavior, we enhance our ability to design more effective prevention programs for all groups.

Contributor Information

Sean Joe, School of Social Work and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Silvia Sara Canetto, Department of Psychology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins.

Daniel Romer, Adolescent Risk Communication Institute, Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia.

REFERENCES

- Beautrais AL. Life course factors associated with suicidal behavior in young people. American Behavioral Scientist. 2003;46:1137–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Bille-Brahe U. Sociology and suicidal behaviour. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A. Climbing Jacob’s ladder: The enduring legacy of African American families. New York: Touchstone; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Recurrent themes in the treatment of African-American women in group psychotherapy. Women & Therapy. 1991;11:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Canetto SS. Meanings of gender and suicidal behavior among adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1997;27:339–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canetto SS, Lester D. Gender and the primary prevention of suicide mortality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1995;25:58–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canetto SS, Lester D. Gender, culture and suicidal behavior. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1998;35:163–191. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide among African-American youths—United States, 1980–1995. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1998;47:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. Atlanta: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Early KE. Religion and suicide in the African-American community. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Early KE, Akers RL. “It’s a white thing”: An explanation of beliefs about suicide in the African-American community. Deviant Behavior. 1993;14:227–296. [Google Scholar]

- Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K. Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:957–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing suicide: A national imperative. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grier WH, Cobbs PM. Black rage. New York: Basic Books; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Pitney B, LaFromboise TD, Basil M, September B, Johnson M. Psychological and social indicators of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in Zuni adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:473–476. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S. Explaining changes in the patterns of black suicide in the United States from 1981–2002: An age, cohort, & period analysis. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32:262–284. doi: 10.1177/0095798406290465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Marcus SC. Trends by race and gender in suicide attempts among U.S. adolescents, 1991–2001. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Romer D, Jamieson P. Suicide acceptability is related to suicidal behavior among U.S. adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37:165–178. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005. What we know and don’t know about suicide; pp. 16–46. [Google Scholar]

- Manderscheid RW, Atay JE, Male A, Blacklow B, Forest C, Ingram L, et al. Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ, editors. Highlights of organized mental health services in 2000 and major national and state trends. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Center for mental health services: Mental health, United States, 2002 (DHHS Pub No. SMA 3938) 2004

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS. African American women’s definitions of spirituality and religiosity. Journal of Black Psychology. Special Issue: African American Culture and Identity: Research Directions for the New Millennium. 2000;26:101–122. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel JS, Purcell D, D’Augelli AR. The relationship between sexual orientation and risk for suicide: Research findings and future directions for research and prevention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;31 Suppl:84–105. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.5.84.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler B, Earls F. Trends in adolescent suicide”: Misclassification Bias? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:150–153. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’ Carroll PW, Berman AL, Maris RW, Moscicki EK, Tanney BL, Silverman MM. Beyound the tower of Babel: A nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1996;26:237–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu J. Minority coping responses and school experience. Journal of Psychohistory. 1991;18:433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps RE, Taylor JD, Gerard PA. Cultural mistrust, ethnic identity, racial identity, and self-esteem among ethnically diverse Black students. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2001;79:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Poussaint AF, Alexander A. Lay my burden down. Boston: Beacon Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Rivera AL. Developing a culturally sensitive treatment modality for bilingual Spanish-speaking clients: Incorporating language and culture in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1995;74:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Stillion JM, Stillion BD. Attitudes toward suicide: Past, present and future. Omega. 1998;37:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Author; Summary of findings from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (DHHS Publication No. SMA 01- 3549, NHSDA Series: H-13) 2003

- Taylor-Gibbs J. African-American suicide: A cultural paradox. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1997;27:68–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Hardison CB, Chatters LM. Kin and nonkin as sources of informal assistance. In: Neighbors HW, Jackson JS, editors. Mental health in black America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. pp. 130–145. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Terrell S, Miller F. Level of cultural mistrust as function of educational and occupational expectations among Black students. Adolescence. 1993;28:572–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ. African American women’s spiritual beliefs: A guide for treatment. Women and Therapy. 2001;23:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. What can suicide researchers learn from African Americans? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:908. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Public Health Service. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National strategy for suicide prevention: Goals and objectives for action. 2001 [PubMed]

- Whaley AL. Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: A review and meta-analysis. Counseling Psychologist. 2001;29:513–531. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Psychometric analysis of the Cultural Mistrust Inventory with a black psychiatric inpatient sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:383–396. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen N, Andrade N, Nahulu L, Makini G, McDermott JF, Danko G, et al. The rate and characteristics of suicide attempters in the Native Hawaiian adolescent population. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1996;26:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuberi T. Thicker Than Blood: An Essay on How Racial Statistics Lie. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]