Abstract

Two-year-olds assign appropriate interpretations to verbs presented in two English transitivity alternations, the causal and unspecified-object alternations (Naigles, 1996). Here we explored how they might do so. Causal and unspecified-object verbs are syntactically similar. They can be either transitive or intransitive, but differ in the semantic roles they assign to the subjects of intransitive sentences (undergoer and agent, respectively). To distinguish verbs presented in these two alternations, children must detect this difference in role assignments. We examined distributional features of the input as one possible source of information about this role difference. Experiment 1 showed that in a corpus of child-directed speech, causal and unspecified-object verbs differed in their patterns of intransitive-subject animacy and lexical overlap between nouns in subject and object positions. Experiment 2 tested children’s ability to use these two distributional cues to infer the meaning of a novel causal or unspecified-object verb, by separating the presentation of a novel verb’s distributional properties from its potential event referents. Children acquired useful combinatorial information about the novel verb simply by listening to its use in sentences, and later retrieved this information to map the verb to an appropriate event.

Languages contain systematic relationships between sentence structure and word meaning (e.g., Bloom, 1970; Carlson & Tanenhaus, 1988; Dowty, 1991; Levin & Rappaport-Hovav, 2005). Thus, verbs that describe one participant acting on another tend to occur in transitive sentences, with two noun-phrase arguments (e.g., “She tickled her.”), while verbs that describe one-participant actions tend to be intransitive, with one argument (e.g., “She laughed.”).

Children use these systematic relationships between structure and meaning to constrain the interpretation of new verbs in a process known as syntactic bootstrapping (Landau & Gleitman, 1985). For example, when they encounter a novel verb in a simple transitive sentence, 2-year-olds infer that the verb refers to a relationship between two participants rather than to an action by a single participant (e.g., Fisher, 2002; Naigles, 1990; Naigles & Kako, 1993). Young children also use word order in a transitive sentence to relate a new verb to an event in which the subject of the sentence plays an agent’s role (Gertner, Fisher, & Eisengart, 2006). Somewhat older children infer that an unknown verb has a mental-content meaning (e.g., believe) when it occurs with sentence-complement syntax (e.g., “Matt gorps that his grandmother is under the covers;” Papafragou, Cassidy, & Gleitman, 2007).

In the preceding examples, children used structural elements of a single sentence to guide their interpretation of a novel verb. But syntactic bootstrapping is not limited to inferences from a single sentence. The syntactic bootstrapping view holds that children also gain information about the meaning of a verb from the set of sentence structures in which it occurs (Landau & Gleitman, 1985).

To illustrate, many verbs occur in multiple sentence structures (e.g., transitive and intransitive, see example (1)). Verbs that occur in the same set of structures tend to have similar meanings (Levin, 1993; Pinker, 1989). For instance, verbs that occur in the causal alternation shown in (1) describe actions that cause a salient change in the object acted upon (e.g., an externally-caused motion such as bounce or a change of state such as break); both the action and resulting change are part of the meaning of the verb. Verbs that occur in the unspecified-object alternation shown in (2) are similar to causal verbs in that they describe actions on objects. However, unspecified-object verbs include only the action in their meanings, without reference to any particular result. For instance, while poking someone could result in some effect (e.g., the person poked becomes irritated), only the physical action is described by the verb poking; this action would still be considered poking even in the absence of an effect (see Wagner, 2006, for discussion). Unspecified-object verbs vary more in their meanings than do causal verbs, but many describe contact actions (e.g., dust, poke, push).

- Anne broke the lamp.

- The lamp broke.

- Anne dusted the lamp.

- Anne dusted.

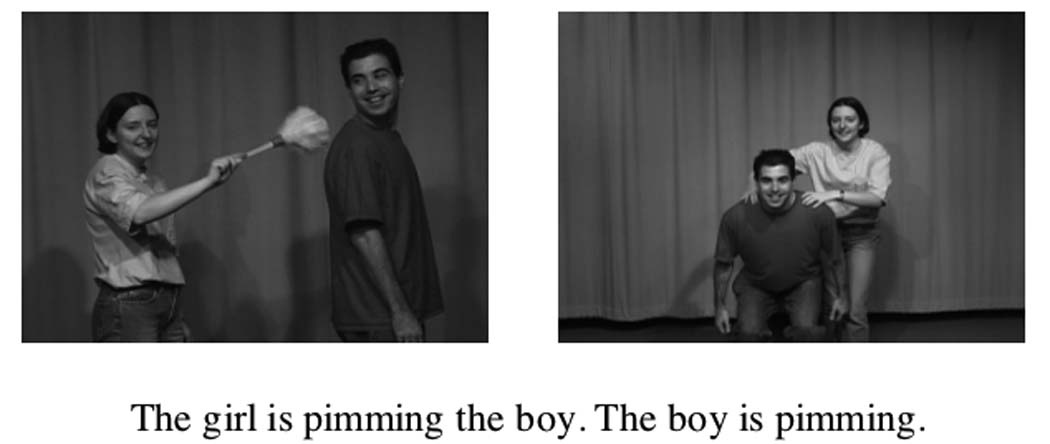

Experimental evidence suggests that children can use sets of frames such as those in (1–2) to draw appropriate inferences about verb meaning (Naigles, 1996, 1998; Scott & Fisher, 2007). For example, in one study, Scott and Fisher (2007) presented 28-month-old children with a caused-motion event (a girl causing a boy to bend at the knees by pressing down on his shoulders) and a contact-activity event (a girl dusting a boy’s back with a feather duster; see Figure 1). These two events were shown simultaneously and were accompanied by a soundtrack in which a novel verb occurred either in the causal or in the unspecified-object alternation. Children who heard the novel verb used in the causal alternation looked longer at the caused-motion event than did those who heard it used in the unspecified-object alternation.

Figure 1.

Contact-activity (left) and caused-motion (right) test events and accompanying soundtrack (causal condition) from Scott and Fisher (2007).

The present research asked how children use the alternations shown in (1) and (2) to assign different meanings to causal and unspecified-object verbs. The two alternations are syntactically identical: Both involve a transitive and an intransitive sentence. Moreover, the two alternations assign similar roles to the subject and object arguments of the transitive sentence of each pair (1a, 2a): both types of verbs assign the agent of action to the subject position and the recipient of action (the undergoer) to object position. The difference between the two alternations lies in the semantic roles assigned to subject position in the intransitive sentence of each pair. In intransitive sentences, unspecified-object verbs assign the agent to the subject position (2b), just as they do in transitive sentences. In contrast, causal verbs assign the undergoer to this position (1b). In order to assign appropriately different interpretations to novel verbs presented in these two alternations, children must be able to distinguish agent-subject from undergoer-subject intransitive sentences. The two syntactic cues that have been shown to influence young children's verb interpretation, verb transitivity and word order in transitive sentences (e.g., Naigles, 1990; Gertner et al., 2006), would not help children differentiate these two types of intransitive sentences. The finding that 28-month-olds interpret these alternations appropriately (Naigles, 1996, 1998; Scott & Fisher, 2007) suggests that they have access to another source of information, one that reflects the underlying role difference between the two alternations.

One likely source of role information is the referential scene. In experiments with adults, Knoeferle, Crocker, Scheepers, and Pickering (2005) showed that when an ambiguous sentence is accompanied by a relevant referential scene, the apparent roles of the scene participants constrain the adults’ assignment of semantic roles to the noun phrases in the sentence. It has long been assumed that children's sentence comprehension exploits the constraints of the referential context in much the same way (e.g., Chapman & Miller, 1975; Clark, 1973; Huttenlocher, 1974; Shatz, 1978). If children encountered the alternations in (1–2) in the presence of relevant referential scenes, as they did in the experiments by Naigles (1996, 1998) and by Scott and Fisher (2007), then in principle they could use the referential scene to assign likely semantic roles to the noun phrases within each alternation. For instance, in Scott and Fisher’s (2007) study, children in the unspecified-object condition might have concluded that “The girl is pimming” was an agent-subject intransitive sentence because the girl played an agent role in the accompanying test events.

A second source of role-relevant information that could be useful even in the absence of an informative referential setting comes from the distributional properties of the sentences in the input. In an examination of text from the Wall Street Journal, Merlo and Stevenson (2001) found that causal and unspecified-object verbs systematically varied on a number of distributional features, and that a machine-learning model could reliably use these features to distinguish between the two verb types. Merlo and Stevenson’s model relied primarily on three features: each verb’s frequency of occurrence in the transitive structure (transitivity), its rate of subject-noun animacy, and the degree of lexical overlap between the nouns in its subject and object positions.

How might these features help identify causal versus unspecified-object verbs? Unspecified-object verbs (2) assign the same role (agent) to subject position regardless of transitivity. These verbs have mostly animate subjects (because all their subjects are agents, which tend to be animate), and they rarely have the same lexical items in subject and object position (because all their subjects are agents and their objects are undergoers). In contrast, causal verbs (1) assign the undergoer role to the object of the transitive sentences and to the subject of the intransitive sentences. These verbs have fewer animate subjects (because their intransitive subjects are undergoers, which tend to be inanimate) and are more likely to have the same lexical items in subject and object position (because their objects and intransitive subjects are both undergoers).

Could young children use the distributional cues identified by Merlo and Stevenson (2001) to distinguish causal and unspecified-object verbs? In order to so, children must be able to (1) detect and keep track of all three distributional cues, and (2) use these distributional cues to draw inferences about verb meaning. There are encouraging hints that young children possess these abilities.

Previous evidence suggests that both adults (e.g., Wonnacott, Newport, & Tanenhaus, 2008) and children (e.g., Gordon & Chafetz, 1990; Kidd, Lieven, & Tomasello, 2006; Snedeker & Trueswell, 2004; Yuan & Fisher, 2006, in press) keep track of the sentence structures in which a verb has appeared. For example, in recent work by Yuan and Fisher (2006, in press), 28-month-old children watched videotaped dialogues in which two people repeatedly used a made-up verb in either only transitive sentences (e.g., A: “Anna blicked the baby!” B: “Really, she blicked the baby?”) or only intransitive sentences (A: “Anna blicked!” B: “Really, she blicked?”). The children later heard the verb used in isolation (“Find blicking!”) while they viewed test videos depicting two referential options: a two-participant causal action (one girl lifted and lowered another girl’s leg) and a one-participant action (a girl made arm-circles). Children who had previously heard the verb used in transitive sentences looked longer at the two-participant event than did children who had heard the verb used in intransitive sentences. This and other results suggested that the children learned whether the verb was transitive or intransitive simply by hearing it used in sentences, even though they did not yet know the verb’s semantic content. When later presented with the verb in a referential context, children retrieved this syntactic-distributional information and used it to select an appropriate referent for the verb.

Previous work also suggests that children keep track of role-relevant information about the nouns that occur with verbs. Children keep track of the animacy of nouns in various grammatical positions. For example, 2-year-olds better comprehend sentences with animate than inanimate subjects, suggesting some sensitivity to the tendency for subject noun phrases to be animate (Childers & Echols, 2004; Corrigan, 1988; Lempert, 1989). Two-year-olds also use knowledge of the animacy of likely argument role-fillers for a particular verb in sentence comprehension: for example, they inferred that an unfamiliar noun must refer to an animal if it was the object of feed (“Mommy’s feeding the ferret!”; Goodman, McDonough, & Brown, 1998; see also Corrigan & Stevenson, 1994; Fernald, 2007). Children’s ability to track the distributions of particular lexical items relative to one another is also well documented. Infants track syllable co-occurrences in artificial grammar-learning experiments (e.g., Gómez, 2002; Saffran, Aslin, & Newport, 1996), and early sentence production reflects word combinations that are frequent in the input (e.g., Rowland, 2007).

Can young children use distributional features to assign meanings to novel verbs that occur in the causal and unspecified-object alternations? We examined this question in two parts. In Experiment 1, we sought to verify that the features identified by Merlo and Stevenson (2001) reflected the semantic roles assigned by causal and unspecified-object verbs in a corpus of child-directed speech. Having determined that relevant distributional cues occur in child-directed speech, in Experiment 2 we used the dialogue-training method described earlier to examine 2-year-olds’ ability to use these distributional cues to infer the meaning of a novel alternating verb. In the General Discussion, we will speculate about two possible mechanisms by which young children might use distributional cues to draw such inferences.

Experiment 1

The Wall Street Journal corpus that Merlo and Stevenson (2001) analyzed differs in many ways from casual speech to children; for example, child-directed speech consists of much shorter sentences, is more repetitive, and employs a simpler vocabulary (e.g., Bard & Anderson, 1994; Newport, Gleitman, & Gleitman, 1977). Moreover, the same common verbs are almost certainly used in different senses in newspaper text and in casual speech to children (e.g., The corporation folded versus Let's fold the laundry). Such verb-sense differences across different discourse registers are important because they can cause striking differences in the frequency with which the same verb occurs in particular sentence structures (e.g., Roland & Jurafsky, 2002). Given these differences, it cannot be assumed that transitivity, subject animacy, and lexical overlap would identify the argument-structure patterns of the causal and unspecified-object alternations in child-directed speech just as they did in Merlo and Stevenson’s (2001) newspaper text.

To get at this issue, we examined the distributions of transitivity, subject animacy, and lexical overlap for causal and unspecified-object verbs in a large sample of child-directed speech. We then used an unsupervised learning algorithm, k-means clustering, to determine whether the distributions of these features differentiated the two groups of verbs.

Method

Materials

We selected the following part-of-speech tagged corpora from the CHILDES database (MacWhinney, 2000): Bloom 1970, Brown, Clark, Demetras Working, Higginson, Kuczaj, New England, Post, Suppes, and Warren-Leubecker. From these corpora we selected all transcripts in which the target child was 32 months old or younger (range 13.5–32 months). These transcripts contained 112,000 parental utterances.

We used the CLAN program to search the morphological tier of all parental utterances for the “v|” tag1, to obtain a list of all the verbs used by the parents. From this list, we selected all causal and unspecified-object verbs (classification based primarily on Levin, 1993) that occurred at least 30 times in total, and that occurred in at least 5 of the 10 corpora. The 29 verbs that met these criteria appear in Table 1. These verbs were used in 12,521 parental utterances across all the selected corpora.

Table 1.

Verbs Used in Experiment 1

| Verb class | Selected verbs |

|---|---|

| Undspecified- | bite, draw, drink, eat, hit, play, pull, push, read, see, |

| Object | throw, tickle, try, wash, write |

| Causal | bounce, break, change, close, fold, move, open, pop, roll, |

| shut, slide, spill, tear, turn | |

Coding

The first author hand-corrected the part-of-speech tagging of all 12,521 parental utterances containing the 29 selected verbs. The corrected utterances were coded with the CLAN program using the search heuristics described below. All coding was hand-checked by the first author.

Transitivity

Utterances containing the target verbs were coded as transitive if the verb was immediately followed by a noun, a pronoun, a determiner (e.g., a, the), or any of a set of quantifiers (some, any, all, much, and more). An utterance was coded as intransitive if the verb was immediately followed by a punctuation mark, a conjunction (e.g., and, or), a preposition, a locative phrase (e.g., here), another verb, or a filler (e.g., uh-oh). Utterances containing phrasal verbs (e.g., “He tore up the paper.”) were hand-corrected to be transitive. Utterances in which the verb was followed by a part of speech other than those described above could not be reliably classified using machine-coding heuristics and were excluded. The final data set, after transitivity coding, consisted of 11,748 utterances.

Animacy

Following Merlo and Stevenson (2001), we used pronouns as a machine-extractable approximation of animacy. Pronoun arguments are very frequent in child-directed speech (e.g., Laakso & Smith, 2007) and 2-year-olds more readily understand transitive sentences when subjects and objects are pronouns marked for animacy (e.g., He [verb] it; Childers & Tomasello, 2001). This suggests that children know the meanings of many pronouns from an early age and might be able to use them to track the animacy of each verb’s arguments.

An utterance was coded as having an animate subject if the verb was preceded by he, she, we, I, you, let’s or who, permitting one intervening auxiliary verb. Imperatives were also coded as having animate subjects2. Inanimate subjects were it, that, this, that one, this one, or what. These heuristics captured 75% of the subjects in the data set.

Lexical overlap

To calculate the lexical overlap between subject and object noun-phrases for each verb, we followed the procedure outlined by Merlo and Stevenson (2001): We extracted the subject and object noun-phrases of each sentence containing a target verb. The subject-noun set for each verb contained all nouns and pronouns that occurred as subjects of the verb in either transitive or intransitive sentences; the object-noun set contained all nouns and pronouns that occurred as objects of the verb. We then found all nouns that occurred in both the subject- and object-noun set for a particular verb. We selected the set in which the noun was more frequent and added its number of occurrences in that set to the overlap set for the verb. For example, if break had the subject set {pencil, Adam, it, it, baby} and the object set {pencil, it, it, it, glasses}, the overlap set would be {pencil, it, it, it}. We then divided the number of items in the overlap set by the total number of subjects and objects for that verb (in this example, 4/10 = 40% lexical overlap). In determining the overlap set, noun number (e.g., pencil vs. pencils) and case (he vs. him) were ignored.

Measures

We assigned to each verb a score for each of four variables: transitivity (the proportion of coded utterances that were transitive), overall subject animacy (the proportion of coded subjects that were animate), intransitive-subject animacy (the proportion of coded intransitive subjects that were animate), and lexical overlap as defined above. Intransitive-subject animacy was examined separately because of its predicted importance in distinguishing causal and unspecified-object verbs. Transitive-subject animacy was not examined separately because 99% of transitive subjects were animate and this did not vary by verb class (causal mean = 99%; unspecified-object mean = 99%).

Classification analyses

In their classification analyses, Merlo and Stevenson’s (2001) machine-learning algorithm learned to classify the verbs via discriminant analysis based on explicit feedback about the correct classification of a training subset of verbs. Supervised learning procedures of this type are generally considered a poor model for ordinary language acquisition, as children receive no direct feedback about the proper classification of verbs they have learned. To approximate this aspect of language acquisition, we chose to classify the verbs using k-means clustering (MacQueen, 1967), an algorithm that does not receive direct feedback about correct classification. Note that while an unsupervised learning algorithm is more similar to the circumstances of language acquisition than a supervised algorithm, we do not presume that language learners use a process like k-means clustering to acquire and classify verbs. Rather, this clustering analysis is simply a tool for determining whether particular cues could be used to detect category divisions in the input.

K-means clustering takes scores on p variables (i.e. the scores described above) for n objects (i.e. verbs) and attempts to organize those objects into k clusters. The algorithm forms a random initial division of the p-dimensional similarity space into k clusters and then iteratively reorganizes the objects to minimize the sum, over all clusters, of the within-cluster distance between each object and the center of its cluster. Once reorganization of the objects can no longer reduce the total within-cluster distance, the algorithm stops. K-means clustering is sensitive to the initial random partitioning of the data, sometimes returning solutions that are not the best fit for the data. The standard procedure for avoiding suboptimal fits is to repeat the analysis with different random initial divisions of the data and to select the solution with the lowest total within-cluster distance as the best fit for the data. For each analysis reported here, we performed 100 replications.

The k-means clustering algorithm requires that the number of clusters, k, be specified in advance. For all the analyses reported here, 2 clusters were used. Since children do not know a priori how many classes of verbs they are likely to encounter in the input, this aspect of the analyses is a poor approximation of natural language acquisition. However, pilot analyses with other numbers of clusters (3 and 4) produced poorly separated clusters. This hints that, within the set of transitivity-alternating verbs, children might naturally arrive at 2 groups of verbs, as exploratory attempts with other numbers of groups would fail to produce cohesive clusters of verbs.

Cluster evaluation

Two measures were used to evaluate the results of each clustering analysis. We first calculated the proportion of verbs correctly classified (accuracy). That is, each verb was counted as correctly classified if its a priori categorization as shown in Table 1 matched that of the majority of verbs in its cluster. Because this accuracy score sometimes overestimates the quality of a clustering solution, we also calculated the Adjusted Rand Index (Radj; Hubert & Arabie, 1985), which measures the overall quality of a clustering solution by taking into account both correct classifications and incorrect classifications. The index ranges from 0 (random grouping) to 1 (perfect classification), with occasional negative values for extremely poor solutions.

To provide a baseline for the obtained accuracy and Radj scores, we created a reference distribution of randomly-obtained scores via Monte Carlo sampling. That is, we created 5,000 random permutations of the data (by randomizing the assignment of transitivity, animacy, and lexical-overlap scores to particular verbs), submitted them to the k-means clustering algorithm, and obtained Accuracy and Radj scores for the resulting clusters. Separate reference distributions were created in this way for each analysis reported below. P-values were calculated as the proportion of scores in the reference distribution that were as or more extreme than the score obtained in the experimental analysis.

Results

Table 2 shows the mean scores for each variable, separately by verb class. As expected, unspecified-object verbs had animate subjects more often than did causal verbs (t(27) = 3.197, p < .01). This difference was greater for intransitive-subject animacy than for subject animacy overall: only 44% of the intransitive sentences containing causal verbs had animate subjects, whereas 97% of the intransitive sentences containing unspecified-object verbs had animate subjects (t(27) = 6.913, p < .001). Causal verbs also exhibited marginally higher lexical overlap than unspecified-object verbs (t(27) = 1.971, p = .061). The two verb groups did not differ in transitivity in this sample (t < 1).

Table 2.

Mean (SD) Scores, Separately by Verb Class

| Causal | Unspecified-object | |

|---|---|---|

| Transitivity | .71 (.20) | .67 (.22) |

| Overall subject animacy | .87 (.12) | .98 (.05) |

| Intransitive-subject animacy | .44 (.27) | .97 (.09) |

| Lexical overlap | .44 (.14) | .29 (.26) |

We performed five k-means clustering analyses, one using each variable alone and one using all variables. Table 3 shows the accuracy and Radj scores for each cluster analysis. The p-values shown in the Table were obtained from reference distributions created through Monte Carlo sampling, as described in the Methods section. The clustering solution based on all variables, shown in the bottom row of Table 3, yielded highly accurate verb classification, grouping 24 of the 29 verbs correctly. Its Radj of .41 represents a significant improvement over the randomly-generated baseline. Neither transitivity nor overall subject animacy yielded classifications that differed from the random baseline when considered alone. Intransitive-subject animacy yielded the best classification; with 24 out of 29 verbs correctly classified, it performed as well as the analysis using all variables. The analysis based on lexical overlap classified 20 of the 29 verbs correctly, with a significant Radj of .12.

Table 3.

Accuracy (Proportion of Verbs Classified Correctly) and Adjusted Rand Index (Radj) Scores for k-Means Clustering Solutions Based on Each Variable, and on All Variables

| Variable used | Accuracy | Radj | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transitivity | .59 | −.001 | .43 |

| Overall subject animacy | .62 | .04 | .17 |

| Intransitive subject animacy | .83 | .41 | .0004 |

| Lexical overlap | .69 | .12 | .04 |

| All variables | .83 | .41 | .0004 |

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 show that child-directed speech contains distributional features that discriminate causal from unspecified-object verbs. The individual feature analyses provide some insight into which of these features would be most useful for making this distinction.

In our corpus, unlike in Merlo and Stevenson’s (2001), both verb types were equally likely to be transitive, causing transitivity to perform poorly in classification analyses. Such differences between corpora are generally unsurprising and, as mentioned above, can be partially attributed to differences in the distribution of verb senses in different corpora (Roland & Jurafsky, 2002). For instance, in our data the verb fold was used primarily in the context of doing laundry (e.g. “Let’s fold it [the towel] nice and neat.”) and therefore the uses of this verb were predominantly transitive (73%). It is unlikely that the Wall Street Journal contains the sense of fold that pertains to laundry. Instead, in the Wall Street Journal, fold is probably used to refer to events such as the collapse of a corporation (e.g. “After serious financial trouble, the company folded.”), resulting in a much lower rate of transitivity (23%; Merlo & Stevenson, 2001). Although we did not code for verb sense, it seems likely that differences in discourse context and style between the two corpora led to many sense differences like those seen with fold, and that these differences contributed to the different transitivity patterns.

The high transitivity rate in our corpus also affected the animacy results. Because both causal and unspecified-object verbs assign an agent to the transitive subject position, the transitive subjects were mostly animate, regardless of verb class. For the overall subject animacy measure, this large number of animate transitive subjects obscured any differences in subject animacy between the two verb types. As a result, overall subject animacy failed to classify the verbs in our data set.

Once the uniformly animate transitive subjects were removed, however, the difference between the two groups became apparent. Intransitive-subject animacy classified most of the verbs correctly, performing as well as a model considering all of the predictors together. Merlo and Stevenson’s (2001) lexical overlap measure also performed well in our analyses. Thus, linking animacy with syntactic positions and tracking lexical overlap between syntactic positions are both useful cues for distinguishing causal and unspecified-object verbs in corpora as diverse as the Wall Street Journal and casual speech to children.

These results suggest that the input contains distributional features that would allow children to distinguish between causal and unspecified-object verbs. Many questions remain about how children would use these features to discover verb categories in the input. For instance, in the analyses presented here, only relevant features were presented to the classification algorithm. In natural language acquisition, learners must determine both how many categories are present in the input and which cues are relevant to each. In principle, the set of cues could be unbounded, resulting in an intractably large search space for useful distributionally-defined categories. Proposed solutions to this problem typically adopt some combination of two theoretical tactics. First, children’s initial search space for discovering grammatical categories and subcategories is assumed to be constrained because children are predisposed to attend to a subset of the conceivable cues, the grammatically-relevant ones (e.g., Gleitman, 1990; Pinker, 1989). Second, as children learn about words and structures, the apparent meanings of those words and structures provides semantic feedback for learning. This feedback, while noisy, could help children to determine which distributional cues are diagnostic of meaning differences (e.g., Maratsos & Chalkley, 1980; Pinker, 1989).

In the present case, the cues that we used – verb transitivity, subject noun-phrase animacy, and lexical overlap between subject and object positions – are clearly grammatically relevant features. In addition, the usefulness of these cues is not limited to telling apart causal and unspecified-object verbs. Cues based on the nouns and pronouns that appear in various argument positions are informative for discriminating a number of meaningfully distinct classes of verbs (e.g., Joanis, Stevenson, & James, 2008; Laakso & Smith, 2007; Pinker, 1989; Resnik, 1996). We will return to these issues in the General Discussion, and propose two mechanisms whereby children could use the distributional cues examined here to draw inferences about verb meaning.

Experiment 2

The results of Experiment 1 showed that child-directed speech contains at least two useful distributional cues to the differences between causal and unspecified-object verbs: intransitive-subject animacy and the lexical overlap between nouns in subject and object position. In Experiment 2, we asked whether 28-month-old children could use these distributional cues to guide the interpretation of an unknown verb. To isolate the contribution of distributional cues, we presented the new verb’s distributional properties separately from its possible event referents using the dialogue-training technique introduced by Yuan and Fisher (2006, in press). This task is a modification of the standard looking-preference comprehension task, which relies on the well-established tendency of children and adults to look at scenes related to sentences they hear (e.g., Tanenhaus, Spivey, Eberhard, & Sedivy, 1995).

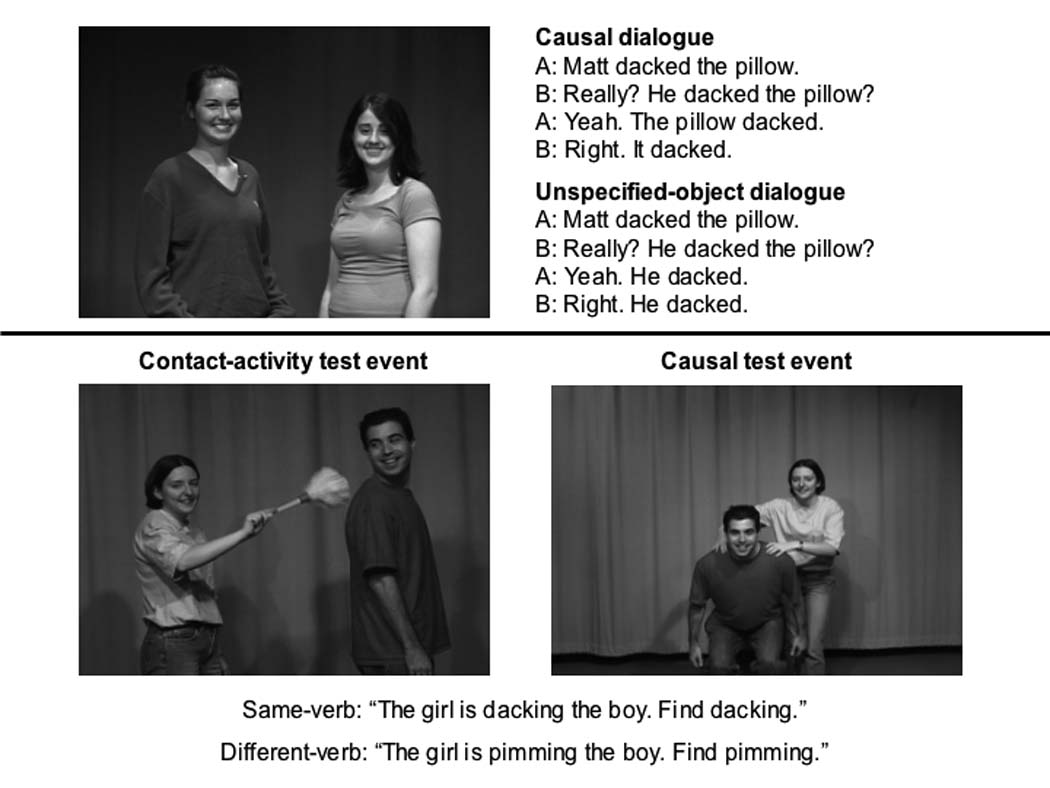

Children first watched a video of two women using the novel verb dacking in a conversation. Depending on the dialogue condition, the conversation exhibited the animacy and lexical overlap patterns of either the causal or the unspecified-object alternation (Figure 2). All children then viewed the two test events shown in Figure 2 and heard “The girl is dacking the boy! Find dacking.” The causal event showed a girl causing a boy to squat by pressing down on his shoulders. The contact-activity event showed the girl brushing the boy's back with a feather duster.

Figure 2.

Training and test phases for the novel verb (Experiment 2). Test events: Contact-activity event (left) and caused-motion event (right).

Because both dialogue groups heard the same transitive sentence while viewing the test events, any differences between the groups in the interpretation of the novel verb could be attributed to the distributional information manipulated in the dialogues. If children can use verbs’ distributional properties as a source of role-relevant information, then those who heard the causal dialogue should assign a causal interpretation to the verb and thus look longer at the caused-motion event; those who heard the unspecified-object dialogue should assign an activity interpretation and thus look longer at the contact-activity event.

We also included control conditions in which children heard one of the dacking dialogues, but heard a different verb when the test events were presented (“The girl is pimming the boy. Find pimming.”). Since the children in these control conditions had not encountered pimming in the dialogues, they should treat the dialogues as irrelevant to the test trials. We therefore predicted that in the control conditions, children in the two dialogue groups would not differ in their looking patterns.

Method

Participants

Forty-eight 28-month-olds participated (mean 28.1, range 27.0–30.0, 24 male, 24 female). All were native speakers of English. Five additional children were excluded due to parental interference (1), failure to complete the experiment (1), or because they moved out of camera range (3). Children’s productive vocabulary was measured using the short form of the Bates-Macarthur CDI, Level 2 (Fenson, Pethick, Renda, Cox, Dale, & Reznick, 2000). Vocabulary scores ranged from 15 to 100 with a median of 70. Twelve children were randomly assigned to each of the four combinations of the dialogue (causal, unspecified-object) and test-verb (same-verb, different-verb) conditions.

Apparatus

Children sat on a parent’s lap facing two 20-inch television screens placed 30 inches away. The screens were 12 inches apart and about at the child's eye level. Soundtracks were played from a concealed central speaker. A camera hidden between the two screens recorded the children’s eye movements during the experiment. Parents wore opaque sunglasses, preventing them from biasing their children’s responses.

Materials and Procedure

Stimulus materials were color videos of dialogues between two women and of test events depicting actions involving a girl and a boy. Test events were shown in synchronized pairs and accompanied by a soundtrack recorded by a native English speaker. The left-right positioning of the familiarization, practice, and test events was counter-balanced with dialogue and test-verb condition.

The procedure had three phases: character-familiarization, practice, and test. The character familiarization and practice phases were designed to acquaint the children with the actors in the test events and with the structure of the experiment.

In the character-familiarization phase, a female actor was shown waving on one screen (4s) and was labeled twice (e.g., “There’s a girl!”) while the other screen remained blank. Following a 2-s interval, a male actor was introduced on the other screen in the same manner (“There’s a boy!”). This was followed by two 4-s trials, separated by 2-s blank-screen intervals. In each trial, the girl appeared on one screen while the boy appeared on the other. In the first trial, children were asked to “Find the boy!;” in the second trial they were instructed to “Find the girl!”

In the practice phase, two familiar intransitive verbs were presented. Children first watched two women using the verb jump in 8 sentences in a conversation (e.g., “Matt jumped!” “Yeah, he was jumping”). The conversation was presented in two dialogue video-clips (each 16 – 18s long), each of which contained 4 sentences, separated by a 3-s blank-screen interval. The same dialogue video appeared on both screens simultaneously. Next, during a 7-s blank-screen interval, children heard “Look! Jumping!” Children then saw a pair of 8-s videos, one showing the boy jumping and the other showing the boy pretending to sleep; the soundtrack asked children to “Find jumping.” After a 3-s interval, this 8-s video pair was presented again, and children were again asked to “Find jumping.” Following a 4-s blank-screen interval, this procedure was repeated with a second practice verb (clap); the videos showed the girl clapping and the girl pretending to eat.

Finally, the novel verb dack was introduced. Children first encountered the verb in three dialogue clips (each 18 – 22 s), each of which presented 4 sentences containing the novel verb. In both dialogue conditions, children heard the novel verb in 12 sentences, 6 transitive and 6 intransitive (the complete dialogues appear in the Appendix). Depending on dialogue condition, dacking was presented in either the causal or the unspecified-object alternation (see Figure 2). The two dialogue conditions differed in their patterns of animacy and lexical overlap. In the causal dialogues, 67% (4/6) of the intransitive subjects were inanimate, and the nouns that served as objects of transitive sentences were always re-used as subjects of intransitives. In the unspecified-object dialogue, none of the subjects were inanimate and the nouns that served as subjects of transitive sentences were re-used as the subjects of intransitives. The nouns used in these dialogues did not obviously label the actors in either test event.

Next, during a 7-s blank-screen interval following the third novel-verb dialogue, children in the same-verb groups heard, “Watch! The girl is gonna dack the boy!” The children then saw a pair of 8-s videos, one depicting a caused-motion and the other a contact-activity event (Figure 2). These events were accompanied by the sentence, “The girl is dacking the boy. Find dacking.” As in the practice phase, the pair of videos was presented twice, separated by a 3-s interval. These two 8-s trials tested children's interpretations of the novel verb.

The different-verb groups received the same dialogues and the same test trials as the same-verb groups, with one key difference: The transitive sentences that accompanied the novel-verb test events contained the verb pim instead of dack (“The girl is gonna pim the boy!”).

Analyses

We coded where children looked (left-screen, right-screen, away) frame by frame from silent video. To assess reliability, 12 children’s data were independently coded by a second coder. The first and second coders agreed on the children’s direction of gaze for 96% of coded video frames.

The amount of time children spent looking away from the two video screens during the test trials was analyzed by means of a 2 × 2 × 2 mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with dialogue (causal or unspecified-object) and test verb conditions (same-verb or different-verb) as between-subjects factors, and test-trial as a within-subjects factor. No effect was significant, all Fs < 2.5 and all ps > .1, suggesting that the children in the two experimental and two control groups tended to look away about equally, and equally briefly, during the test trials (same-verb: causal M = .40 s, SD = .50, unspecified-object M = .43 s, SD = .49; different-verb: causal M = .37 s, SD = 32; unspecified-object M = .44 s, SD = .43). Given the uniformity of time spent looking away, we conducted our main analyses on a single measure, the proportion of looking time to the caused-motion event, out of the total time spent looking at either test event during each test trial. Analyses based on absolute looking times to the caused-motion or to the contact-activity event revealed the same pattern of significant effects as the main analyses reported below.

Preliminary analyses of children’s looking time performance in the test trials revealed no interactions of dialogue and test-verb with sex or with whether the child’s vocabulary or performance in the practice trials was above or below the median, all Fs < 1. These factors were not examined further.

Results and Discussion

Table 4 shows the proportion of looking time to the caused-motion event, out of the total time spent looking at either test event during each test trial, separately by dialogue and test-verb condition. As predicted, dialogue type strongly affected looking preferences in the test trials, but did so only for children in the same-verb condition. Inspection of Table 4 suggests that this effect emerged on the second trial.

Table 4.

Mean(SD) Proportion of Looking Time to the Caused-Motion Event During Each 8s Test Trial, Separately by Dialogue and Test-Verb Condition

| Test verb | Dialogue | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same-verb | Causal | .45 (.24) | .77 (.18) | .61 (.17) |

| Unspecified-object | .44 (.22) | .33 (.31) | .39 (.21) | |

| Different-verb | Causal | .47 (.25) | .38 (.23) | .43 (.19) |

| Unspecified-object | .43 (.15) | .40 (.33) | .41 (.17) | |

A 2 (dialogue: causal, unspecified-object) by 2 (test-verb: same-verb, different-verb) by 2 (trial) mixed-model ANOVA revealed a main effect of dialogue (F(1,44) = 4.792, p < .05), marginal interactions of dialogue and test-verb condition (F(1,44) = 3.985, p = .052), trial and dialogue (F(1,44) = 3.823, p = .057), and trial and test-verb (F(1,44) = 3.179, p = .081), as well as a reliable three-way interaction of dialogue, test-verb, and trial (F(1,44) = 7.242, p = .01). To further investigate the 3-way interaction involving trial, we performed separate ANOVAs for each test-verb condition.

An analysis of the different-verb condition revealed no significant effects of dialogue or trial and no significant interaction of these two factors, all Fs < 1. The absence of an effect of dialogue in the different-verb condition suggests that children used the presentation of the verb in the test trial as a cue to retrieve what they knew about this verb. When the verb in the test trials was entirely new, the information from the dialogue was treated as irrelevant.

Analysis of the same-verb condition revealed a significant effect of dialogue (F(1,22) = 8.216, p < .01), a marginal effect of trial (F(1,22) = 3.085, p = .093), and a significant interaction of dialogue and trial (F(1,22) = 12.102, p < .005). As shown in Table 4, during the first trial children in the same-verb condition looked about equally at the two test events regardless of dialogue condition (t < 1). In the second trial, children who heard the causal dialogue looked significantly longer at the caused-motion event than did those who heard the unspecified-object dialogue (t(22) = 4.231, p < .001).

During the test portion of the 2-phase procedure, all children encountered the verb in a transitive sentence. If children’s attention to the test events were influenced only by that sentence, then the two dialogue groups should have shown the same looking patterns. The effect of dialogue in the same-verb condition suggests that children encoded useful distributional information about the new verb during the preceding dialogues, retrieved that information when they encountered the verb again in the test trials, and used it to select an appropriate referent event. The emergence of this effect on the second trial suggests that the task was not easy for the children. The apparent difficulty of this task is not surprising: When the test events appeared, children had to inspect the two novel events to understand their structure, identify the novel verb in the transitive test sentence, and retrieve what they had learned about this verb during the dialogue. Any or all of these steps could contribute to the relatively slow appearance of the dialogue effect during the test trials in the same-verb group.

General Discussion

Previous experiments have shown that children assign appropriately different interpretations to verbs presented in the causal and unspecified-object alternations (Naigles, 1996, 1998; Scott & Fisher, 2007). Here we explored how they might do so. Causal and unspecified-object verbs are syntactically similar in that they can be either transitive or intransitive, but they differ in the semantic roles they assign to the subjects of intransitive sentences. Causal verbs assign an undergoer to this position (The lamp broke), while unspecified-object verbs assign an agent to this position (Anna dusted). In order to tell apart verbs presented in these two alternations, children must detect this difference in role assignments. In the present study, inspired by computational work by Merlo and Stevenson (2001), we examined distributional features of the input as a potential source of information about this role difference.

The results of Experiment 1 showed that child-directed speech contains distributional cues that reflect the underlying argument-structure differences between causal and unspecified-object verbs. Specifically, both intransitive-subject animacy and the lexical overlap between nouns in subject and object position proved useful for discriminating the two verb types. The results of Experiment 2 suggest that children can encode some combination of these two cues, and later use them to identify an appropriate referent for novel causal and unspecified-object verbs. These findings broaden what we know about syntactic bootstrapping in three ways.

First, the results of Experiment 2 confirmed the key findings of Yuan and Fisher (2006, in press). As in Yuan and Fisher's study, children in the two dialogue groups had access to the same syntactic and visual information during the test phase. Thus, the difference between the two dialogue conditions in the same-verb groups indicates that the children gathered distributional facts about the verb while listening to the dialogues, retrieved this information during the test phase when they heard the verb again, and used it to identify an appropriate referent for the verb. The finding that the different-verb groups did not show an effect of dialogue during the test phase provides evidence that children attached distributional facts to a particular new verb and used the reappearance of the same verb during the test trials as a cue to retrieve that distributional knowledge.

Second, our results extend Yuan and Fisher’s (2006, in press) findings by showing that what children learn from listening experience is not limited to the number of noun-phrase arguments that occur with a new verb. In Experiment 2, children had to gather role-relevant information about the new verb’s arguments from the dialogues in order to successfully identify the referent of the verb in the test phase. The dialogues contained two role-relevant cues: intransitive-subject animacy and lexical overlap between the transitive and intransitive sentences. The finding that the children in the same-verb groups interpreted the new verb appropriately suggests that they extracted from their listening experience information about the lexical items that occurred in the verb’s argument slots and/or a coarse semantic encoding of its arguments (i.e. animate vs. inanimate). Because the dialogue conditions in Experiment 2 differed in both animacy and lexical overlap, we cannot determine which cue children used to succeed in the task. One cue may have been more useful than the other, or children may have required both cues to succeed. Future experiments will disentangle these two information sources, estimating their relative weight in verb interpretation.

Third, our results add to a growing body of evidence that young children represent verbs somewhat independently of the sentential context in which they occur (Fernandes, Marcus, DiNubila, & Vouloumanos, 2006; Naigles, Bavin, & Smith, 2005; Yuan & Fisher, 2006, in press). In the present case, children heard the new verb in a transitive sentence and as a bare gerund (“Find dacking”) at test. In order to select an appropriate referent for the verb at test, however, children had to retrieve information about previous encounters with the same verb in an intransitive sentence. Thus, the results of Experiment 2 suggest that 2-year-olds can use knowledge of a verb observed in one syntactic structure to sensibly interpret that verb in a different structure.

Mechanisms

By what mechanism did children use the distributional information present in the dialogues to constrain their interpretation of the verb? We can envision two classes of mechanisms for the cues we provided, which for ease of discussion we will refer to as the category-mediated and direct-inference mechanisms.

Category-mediated

One possibility is that the children used the distributional cues in the dialogues to assign meaning via previously-learned verb categories. The causal and the unspecified-object alternations define categories of verbs that share both syntactic and semantic similarity. Similar categories are found across languages, but the set of particular verbs that participate in each syntactic alternation appears to be constrained by semantic restrictions that are subtle and language-specific, and thus clearly learned (e.g., Pinker, 1989). For instance, the verb bounce (It bounced/She bounced it), along with other verbs of manner of motion, participates in the causal alternation in English, but the verb fall (It fell./*She fell it), along with other verbs of inherently-directed motion, does not. Once a class that has both syntactic and semantic properties is created, it can be used to make inferences about new words (e.g., Brooks & Tomasello, 1999; Gropen, Pinker, Hollander, Goldberg, & Wilson, 1989; Pinker, Lebeaux, & Frost, 1987).

Existing experimental evidence for such class-based inferences in verb learning comes only from studies with older children (e.g., Ambridge, Pine, Rowland, & Young, 2008; Brooks & Tomasello, 1999; Gropen et al., 1989); however, learners draw inferences of the same kind in learning other categories of words from a very early age. For example, Booth and Waxman (2003) showed that 14-month-olds had different expectations for the meanings of novel words presented as count nouns ("This is a blicket! ") versus adjectives ("This is a blickish one! "). Slightly older children use morphological context to discriminate count nouns from proper names ("This is Blicket! "; Hall & Lavin, 2004). The creation of grammatical categories and subcategories based on semantic and distributional learning, and their use to guide new word-learning, has long been assumed as a core mechanism of syntax acquisition (e.g., Brown, 1957; Maratsos & Chalkley, 1980; Waxman & Markow, 1995).

Such category-mediated inferences could explain the results of Experiment 2. For instance, the children may have previously learned that in English, some verbs that can be both transitive and intransitive share the meaning “action culminating in a noteworthy change.” They might also note that the verbs in this class share distributional features: their intransitive subjects tend to be inanimate and they often have the same nouns in subject and object positions. Upon encountering a new verb that demonstrates these distributional properties, children could extend the meaning of the category to the new verb.

The utility of such an inference in our task does not require that 28-month-olds have already worked out the refined semantic restrictions that help determine which verbs can participate in the causal and unspecified-object alternations in English (i.e. the intricacies that Pinker (1989) termed narrow-range restrictions). Rather, children could succeed in our task via this category-mediated mechanism as soon as they have established a rough category of meanings associated with each alternation. Although this category could be too broad, including meanings that do not participate in the alternation in English, it would still permit children to make useful inferences about new verbs (see Ambridge et al., 2008, for evidence of a broad causal alternation category in 5-year-olds).

Direct-inference

Alternatively, children may have used the distributional cues to infer facts about the new verb directly, without using a previously-learned class. Consider first lexical overlap. Particular nouns differ in their tendency to occur in different grammatical positions. Given such lexical asymmetries, learners could develop expectations about which nouns make good subjects and objects (Resnik, 1996). In principle, this information could be represented both verb-generally and relative to particular verbs (e.g., juice generally makes a better object than a subject, and makes a good object for drink, but not for break), and could be used to infer roles in sentences. For instance, upon encountering the sentences “Matt dacked the pillow” and “The pillow dacked” in Experiment 2, children may have tended to assign the pillow an undergoer role in the intransitive sentence. They could have done so because: (a) in their experience with English, pillow has more often occurred as an object than a subject, so they assumed it played an object-like role, even when it occurred in subject position; or because (b) when they encountered pillow as the object of the transitive sentence, they added it to the set of dackable things and extended this interpretation to its occurrence in the intransitive sentence. By either route, lexical overlap between syntactic positions could yield direct information about likely role assignments for noun-phrases in intransitive subject position.

Turning to animacy, children could again have used this cue to infer role assignments directly rather than via an established syntactic/semantic category of verbs. A number of researchers have proposed that the linguistic system has a built-in tendency to align particular semantic roles with different levels of animacy (e.g., animate → agent, inanimate → patient; Aissen, 1999; Dowty, 1991). The correspondence between semantic roles and animacy could also arise from children’s strong expectations about the capacities of animate and inanimate entities. Toddlers know that animate entities can move on their own while inanimate things cannot, for example (Golinkoff, 1975; Massey & Gelman, 1988; see Luo, Kaufman, & Baillargeon, in press, for a similar distinction in 5-month-old infants). These two routes differ in whether the link between animacy and agency is part of a unique endowment for language acquisition (i.e. a Universal Grammar), or is an effect of conceptual knowledge on language interpretation. However, either of these routes would enable children to infer facts about likely semantic role assignments directly from animacy cues.

Prior evidence suggests that somewhat older children use animacy via one of these routes to infer role assignments. Gelman and Koenig (2001) found that 5-year-olds used animacy to assign roles to the subjects of intransitive sentences containing the verb move. When the subject was animate (“The dog moved”), children assumed it was the agent of its own motion; when the subject was inanimate (“The cup moved”), children were more likely to assume the object was undergoing externally-caused motion. Relatedly, Becker (2007) proposed that preschoolers use subject animacy to distinguish two syntactically confusable classes of verbs, known as control verbs (e.g., want in The sheep wanted to disappear vs. *The hay wanted to disappear) and raising verbs (seem in The sheep seemed to disappear vs. The hay seemed to disappear). The underlying intuition here is that seem cannot have a meaning similar to want if it freely occurs with inanimate subjects. Similarly, the children in Experiment 2 could have inferred that the animate subjects of intransitive sentences in the dialogues were likely to be agents, but that the inanimate subjects (e.g., pillow), which could not initiate action on their own, were better suited to an undergoer role.

The direct-inference mechanism is interesting for two reasons. First, it would provide a route whereby the distributional cues we manipulated, subject animacy and lexical overlap, could be inherently meaningful to children without the prior establishment of a semantic/syntactic subcategory of verbs, and thus could guide early word learning. Second, this mechanism is intriguing because it hints that children may have assigned a partial interpretation to the sentences containing the novel verbs while they listened to the dialogues, even though no referential scene was provided. One way to draw inferences about what types of roles particular entities play is to speculate about what those roles might be, using the ordinary processes of sentence comprehension. Adults watching our dialogue videos have the experience of wondering what it means for the pillow (or Matt) to dack. Children may do the same, using the tentative role assignments that result from their attempts to comprehend the dialogues to interpret the novel verb when they encounter it again in the test phase.

At present, we cannot determine which mechanism the children in Experiment 2 used to interpret the distributional cues provided in the dialogues. As noted above, however, there is clear evidence that older children and adults use both mechanisms to interpret sentences (Ambridge et al., 2008; Brooks & Tomasello, 1999; Gelman & Koenig, 2001; Gropen et al., 1989; Pinker et al., 1987), that category-mediated inferences guide word interpretation even in infancy (e.g., Booth & Waxman, 2003), and that 2-year-olds interpret sentences in part based on the plausible roles that the nouns in various argument positions could play (Chapman & Kohn, 1978). On such grounds we might speculate that the 28-month-olds in our task already relied on a combination of the two mechanisms. We anticipate that the dialogue and test method used here can provide a powerful route for investigating these questions, in future experiments that vary the distributional cues offered in the dialogues, and the referential options provided at test.

The present results provide new evidence of the 2-year-old’s prowess in distributional learning, and the relationship of that learning to the creation of a meaningful lexicon. Ordinary child-directed speech contains distributional cues that can be used to tell apart syntactically confusable classes of verbs. Two-year-olds can detect and retain these useful distributional cues from listening experience alone. The listener who hears “Matt dacked the pillow! And the pillow dacked!” can draw, at best, only highly abstract conclusions about what it means to dack. Despite this referential uncertainty, children encode distributional facts relevant to the characteristics of the nouns that fill its argument slots.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a predoctoral traineeship from NIMH (1 T32 MH1819990) to Rose Scott, by grants from the NIH (HD054448) and NSF (BCS 06-20257) to Cynthia Fisher, and by the Research Board of the University of Illinois. We would like to thank Renée Baillargeon, Yael Gertner, and Sylvia Yuan for helpful comments on our manuscript; the staff of the University of Illinois Language Acquisition Lab for their help in data collection; and the parents and infants who participated in this research.

Appendix

Dialogues Used in Experiment 2, Separately by Dialogue Condition

| Causal | Unspecified-object | |

|---|---|---|

| Dialogue 1: | A: Matt dacked the pillow. | A: Matt dacked the pillow. |

| B: Really? He dacked the pillow? | B: Really? He dacked the pillow? | |

| A: Yeah. The pillow dacked. | A: Yeah. He dacked. | |

| B: Right. It dacked. | B: Right. He dacked. | |

| Dialogue 2: | A: Kelly is gonna dack Adam. | A: Kelly is gonna dack Adam. |

| B: Hmm…she’s gonna dack Adam? | B: Hmm…she’s gonna dack Adam? | |

| A: Yeah. Adam’s gonna dack. | A: Yeah. She’s gonna dack. | |

| B: Great. He’s gonna dack. | B: Great. She’s gonna dack. | |

| Dialogue 3: | A: Jessica is gonna dack the flower. | A: Jessica is gonna dack the flower. |

| B: Wow! She’s gonna dack the flower? | B: Wow! She’s gonna dack the flower? | |

| A: Yeah. The flower is gonna dack. | A: Yeah. She’s gonna dack. | |

| B: Yeah. It’s gonna dack. | B: Yeah. She’s gonna dack. | |

Footnotes

We used part-of-speech tagging in corpora downloaded in February, 2005.

If imperatives are removed from the analyses, the patterns of significance described in the Results section remain the same.

References

- Aissen J. Markedness and subject choice in optimality theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 1999;17:673–711. [Google Scholar]

- Ambridge B, Pine JM, Rowland CF, Young CR. The effect of verb semantic class and verb frequency (entrenchment) on children’s and adults’ graded judgments of argument-structure overgeneralization errors. Cognition. 2008;106:87–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard EG, Anderson AH. The unintelligibility of speech to children: Effects of referent availability. Journal of Child Language. 1994;21:623–648. doi: 10.1017/s030500090000948x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M. Animacy, expletives, and the learning of the raising-control distinction. In: Belikova A, Meroni L, Umeda M, editors. Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America; Cascadilla Proceedings Project; Sommerville, MA. 2007. pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom L. Language development: Form and function in emerging grammars. Cambridge MA: The M.I.T. Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom L, Hood L, Lightbown P. Imitation in language development: If, when and why. Cognitive Psychology. 1974;6:380–420. [Google Scholar]

- Booth AE, Waxman SR. Mapping words to the world in infancy: infants' expectations for count nouns and adjectives. Journal of Cognitive Development. 2003;4:357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PJ, Tomasello M. How children constrain their argument structure constructions. Language. 1999;75:720–738. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. Linguistic determinism and the part of speech. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1957;55:1–5. doi: 10.1037/h0041199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. A First Language: The Early Stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GN, Tanenhaus MK. Thematic roles and language comprehension. In: Wilkins W, editor. Syntax and semantics: Thematic relations. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 263–288. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RS, Kohn LL. Comprehension strategies in two- and three-year-olds: Animate agents or probable events? Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1978;21:746–761. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2104.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RS, Miller JF. Word order in early two and three word utterances: Does production precede comprehension? Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1975;18:355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Childers JB, Echols CH. 2.5-year-old children use animacy and syntax to learn a new noun. Infancy. 2004;5:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Childers JB, Tomasello M. The role of pronouns in young children’s acquisition of the English transitive construction. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:739–748. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EV. Non-linguistic strategies and the acquisition of word meanings. Cognition. 1973;2:161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Clark EV. The young word maker: A case study of innovation in the child’s lexicon. In: Wanner E, Gleitman LR, editors. Language Acquisition: The State of the Art. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1982. pp. 390–425. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan R. Children’s identification of actors and patients in prototypical and nonprototypical sentence types. Cognitive Development. 1988;3:285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan R, Stevenson C. Children's causal attributions to states and events described by different classes of verbs. Cognitive Development. 1994;9:235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Demetras M. Working parents’ conversational responses to their two-year-old sons. University of Arizona: 1989. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Dowty D. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language. 1991;67:547–619. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Pethick S, Renda C, Cox JL, Dale PS, Reznick JS. Short-form versions of the Macarthur communicative development inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2000;21:95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A. Looking while listening: What real-time processing measures reveal about how children and adults use grammatical morphemes in understanding; Paper presented at the 32nd Boston University Conference on Language Development; Boston, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes KJ, Marcus GF, DiNubila JA, Vouloumanos A. From semantics to syntax and back again: Argument structure in the third year of life. Cognition. 2006;100:B10–B20. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C. Structural limits on verb mapping: The role of abstract structure in 2.5-year-olds’ interpretations of novel verbs. Developmental Science. 2002;5:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA, Koenig MA. The role of animacy in children’s understanding of move. Journal of Child Language. 2001;28:683–701. doi: 10.1017/s0305000901004810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertner Y, Fisher C, Eisengart J. Learning words and rules: Abstract knowledge of word order in early sentence comprehension. Psychological Science. 2006;17:684–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleitman LR. The structural sources of verb meanings. Language Acquisition. 1990;1:3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Golinkoff RM. Semantic development in infants: The concepts of agent and recipient. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1975;21:181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez RL. Variability and detection of invariant structure. Psychological Science. 2002;13:431–436. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JC, McDonough L, Brown NB. The role of semantic context and memory in the acquisition of novel nouns. Child Development. 1998;69:1330–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon P, Chafetz J. Verb-based versus class-based accounts of actionality effects in children’s comprehension of passives. Cognition. 1990;36:227–254. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(90)90058-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropen J, Pinker S, Hollander M, Goldberg R, Wilson R. The learnability and acquisition of the dative alternation in English. Language. 1989;65:203–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hall DG, Lavin T. The use and misuse of part-of-speech information in word learning. In: Hall DG, Waxman SR, editors. Weaving a Lexicon. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. pp. 339–370. [Google Scholar]

- Higginson RP. Fixing-assimilation in language acquisition. Washington State University: 1985. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert L, Arabie P. Comparing partitions. Journal of Classification. 1985;2:193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J. The origin of language comprehension. In: Solso RL, editor. Theories in Cognitive Psychology. Potomac, MD: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Joanis E, Stevenson S, James D. A general feature space for automatic verb classification. Natural Language Engineering. 2008;14:337–367. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd E, Lieven E, Tomasello M. Examining the role of lexical frequency in the acquisition and processing of sentence complements. Cognitive Development. 2006;21:93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Knoeferle P, Crocker MW, Scheepers C, Pickering MJ. The influence of immediate visual context on incremental thematic-role assignment: Evidence from eyemovements in depicted events. Cognition. 2005;95:95–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczaj SA. General developmental patterns and individual differences in the acquisition of copula and auxiliary be forms. First Language. 1986;6:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso A, Smith L. Pronouns and verbs in adult speech to children: a corpus analysis. Journal of Child Language. 2007;34:725–763. doi: 10.1017/s0305000907008136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau B, Gleitman LR. Language and Experience: Evidence from the Blind Child. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lempert H. Animacy constraints on preschool children’s acquisition of syntax. Child Development. 1989;60:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Levin B. English verb classes and alternations: A preliminary investigation. Chicago, IL: Chicago, University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Levin B, Rappaport-Hovav M. Argument Realization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Kaufman L, Baillargeon R. Young infants' reasoning about physical events involving inert and self-propelled objects. Cognitive Psychology. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2008.11.001. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen JB. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In: Le Cam LM, Neyman J, editors. Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Math, Statistics, and Probability; Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1967. pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. Third Edition. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Maratsos M, Chalkley M. The internal language of children’s syntax: The ontogenesis and representation of syntactic categories. In: Nelson K, editor. Children’s Language. Vol. 2. New York: Gardner Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Massey C, Gelman R. Preschooler's ability to decide whether a photographed unfamiliar object can move itself. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Merlo P, Stevenson S. Automatic verb classification based on statistical distributions of argument structure. Computational Linguistics. 2001;27:373–408. [Google Scholar]

- Naigles L. Children use syntax to learn verb meaning. Journal of Child Language. 1990;17:357–374. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900013817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naigles LR. The use of multiple frames in verb learning via syntactic bootstrapping. Cognition. 1996;58:221–251. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00681-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naigles LR. Developmental changes in the use of structure in verb learning. Advances in Infancy Research. 1998;12:298–317. [Google Scholar]

- Naigles LR, Bavin EL, Smith MA. Toddlers recognize verbs in novel situations and sentences. Developmental Science. 2005;8:424–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naigles LR, Kako ET. First contact in verb acquisition: Defining a role for syntax. Child Development. 1993;64:1665–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport EL, Gleitman H, Gleitman LR. Mother, I'd rather do it myself: Some effects and noneffects of maternal speech style. In: Snow CE, Ferguson CA, editors. Talking to Children: Language Input and Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1977. pp. 109–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ninio A, Snow C, Pan B, Rollins P. Classifying communicative acts in children’s interactions. Journal of Communications Disorders. 1994;27:157–188. doi: 10.1016/0021-9924(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papafragou A, Cassidy K, Gleitman L. When we think about thinking: The acquisition of belief verbs. Cognition. 2007;105:125–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. Learnability and cognition: The acquisition of argument structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S, Lebeaux DS, Frost L. Productivity and constraints in the acquisition of the passive. Cognition. 1987;26:195–267. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(87)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post K. Negative evidence. In: Sokolov J, Snow C, editors. Handbook of Research in Language Development Using CHILDES. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp. 132–173. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik P. Selection constraints: An information-theoretic model and its computational realization. Cognition. 1996;61:127–159. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(96)00722-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland D, Jurafsky D. Verb sense and verb subcategorization probabilities. In: Merlo P, Stevenson S, editors. The Lexical Basis of Sentence Processing: Formal, Computational, and Experimental Issues. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2002. pp. 325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland CF. Explaining errors in children’s questions. Cognition. 2007;104:106–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffran JR, Aslin RN, Newport EL. Statistical learning by 8-month-old infants. Science. 1996;274:1926–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RM, Fisher C. Combining syntactic frames and semantic roles to acquire verbs. In: Caunt-Nulton H, Kulatilake S, Woo I, editors. Proceedings of the 31st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development; Sommerville, MA: Cascadilla Press; 2007. pp. 555–566. [Google Scholar]

- Shatz M. On the development of communicative understandings: An early strategy for interpreting and responding to messages. Cognitive Psychology. 1978;10:271–301. [Google Scholar]

- Snedeker J, Trueswell JC. The developing constraints on parsing decisions: The role of lexical-biases and referential scenes in child and adult sentence processing. Cognitive Psychology. 2004;49:238–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppes P. The semantics of children’s language. American Psychologist. 1974;29:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus MK, Spivey MJ, Eberhard KM, Sedivy JC. Integration of visual and linguistic information in spoken language comprehension. Science. 1995;268:1632–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.7777863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner L. Aspectual bootstrapping in language acquisition: Telicity and transitivity. Language Learning and Development. 2006;2:51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Warren-Leubecker A, Bohannon JN. Intonation patterns in child-directed speech: Mother-Father differences. Child Development. 1984;55:1379–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman S, Markow DB. Words as invitations to form categories: Evidence from 12- to 13-month-old infants. Cognitive Psychology. 1995;29:257–302. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott E, Newport EL, Tanenhaus MK. Acquiring and processing a verb argument structure: Distributional leanring in a miniature language. Cognitive Psychology. 2008;56:165–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S, Fisher C. "Really, he blicked the cat?": 2-year-olds learn distributional facts about verbs in the absence of a referential context. In: Bamman D, Magnitiskaia T, Zaller C, editors. Proceedings of the 30th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development; Sommerville, MA: Cascadilla Press; 2006. pp. 689–700. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S, Fisher C. "Really? She blicked the baby?”: Two-year-olds learn combinatorial facts about verbs by listening. Psychological Science. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02341.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]