Abstract

The corneal endothelium transports fluid from the corneal stroma to the aqueous humor, thus maintaining stromal transparency by keeping it relatively dehydrated. This fluid transport mechanism is thought to be driven by the transcellular transports of HCO3− and Cl− in the same direction, from stroma to aqueous. In parallel to these anion movements, for electroneutrality, there are paracellular Na+ and transcellular K+ transports in the same direction. The resulting net flow of solute might generate local osmotic gradients that drive fluid transport. However, there are reports that some 50% residual fluid transport remains in nominally HCO3−- free solutions. We have examined the driving force for this residual fluid transport. We confirm that in nominally HCO3−free solutions, 48% of control fluid transport remains. When in addition Cl− channels are inhibited, 30% of control fluid movement still remains. Addition of a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor has no further effect. These manipulations combined inhibit the transcellular transport of all anions, without which there cannot be any net transport of solute and consequently no local osmotic gradients, yet there is residual fluid movement. Only the further addition of benzamil, an inhibitor of epithelial Na+ channels, abolishes fluid transport completely. Our data are inconsistent with transcellular local osmosis and instead support the paradigm of paracellular fluid transport driven by electro-osmotic coupling.

Introduction

The corneal endothelial layer transports fluid at the rate of 3.5–6 μl cm−2 h−1 from its stromal (basolateral) to its aqueous humor (apical) side [1, 2]. It thus counterbalances the swelling tendency of the stroma and maintains normal corneal thickness and transparency. It can be hypothesized that this fluid transport is driven by local osmotic gradients arising from translayer transport of solute in the same direction (local osmosis theory). Consistent with this, there is net transcellular HCO3− transport from stroma to aqueous. This transport is substantial [3, 4], and has been termed the main protagonist responsible for the central function of fluid transport across this layer [4]. There is also a lesser Cl− transport in the same direction due to influx via a basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter [5] and efflux via apical Cl− channels [6, 7]. In parallel to this transport of anions there are paracellular Na+ [3, 8] and transcellular K+ transports (Lim, personal communication; [9]) to conserve electroneutrality. However, in apparent contradiction to this local osmosis paradigm, Hodson [3] and Doughty and Maurice [10] have reported that residual fluid transport is observed in nominally HCO3−- free solutions. Kuang et al. [11] also found residual fluid transport in the absence of HCO3−, and proposed endogenous metabolic generation of CO2 and its hydration by an intracellular carbonic anhydrase as a source of the requisite HCO3−. Bonanno [12] examined intracellular pH regulation in nominally HCO3−-free solution and concluded that there was no significant endogenous CO2 generation. However, he observed cellular acidification upon application of a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, and concluded that such acidification was due to hydration of residual CO2 to HCO3− by an endogenous carbonic anhydrase. He proposed that this source of HCO3− could explain the observations of residual fluid transport; however, his observations were only on pH regulation [12] and were not extended to include possible effects of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors on residual fluid transport across corneal endothelium.

As this controversy has remained unsettled for more than a decade, we have now reexamined the issue by removing sequentially several cellular ionic pathways that contribute to net solute flux and fluid transport. We find that even when virtually all transcellular anion transport has been removed or inhibited, there remains a significant fraction of the normal fluid transport. Under these conditions, there could be no net solute transport, hence no induced osmotic gradients. Therefore, these findings are incompatible with the hypothesis that fluid transport across corneal endothelium is driven by local osmotic gradients. As residual fluid transport is abolished by benzamil, an inhibitor of epithelial Na+ channels, we discuss how our recent model of fluid transport due to electro-osmotic coupling in the tight junction is consistent with these data.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were done with in vitro rabbit corneal preparations. Corneas were obtained from New Zealand albino rabbits (~2 kg) using procedures in accordance with the Guide for the Care of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub. No 85-23, revised 1985). Rabbits were euthanized by injecting a sodium pentobarbital solution into the marginal ear vein. The eyes were enucleated immediately. The cornea was dissected, deepithelialized and mounted in a Dikstein-Maurice chamber [2] held in a thermal jacket at 37 C. The stromal surface was covered with silicone oil, and the endothelial surface was initially perfused with a HEPES-HCO3− Ringer’s solution at a rate of 1.4 ml h−1. The control HEPES-HCO3− Ringer’s solution contained (in mmol/L): 113.9 NaCl, 26.2 NaHCO3, 4.7 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 0.4 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 5.6 Glucose and 10 HEPES. Test solutions had the following composition:

a control solution to which 1mM ouabain was added;

a nominally HCO3−-free solution in which HCO3− in the control solution was replaced with Cl− on an equimolar basis;

a nominally HCO3−-free solution plus 0.05 mM NPPB and O.1 mM niflumic acid to inhibit Cl− and other anion fluxes;

solution (3) plus 0.2 mM ethoxyzolamide to inhibit intracellular and extracellular carbonic anhydrases; and

solution (3) plus 0.01 or 0.1 mM benzamil, an epithelial Na+ channel inhibitor.

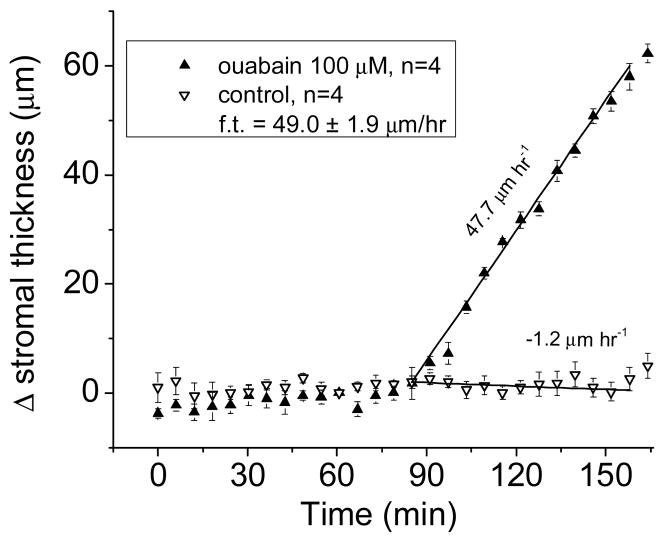

Corneal thickness was determined by specular microscopy using the Dikstein-Maurice method [2] modified à la Klyce to include a computer-controlled microscope, which automatically recorded corneal thickness at 5-minute intervals [13, 14]. Fluid transport per unit area was calculated from the rates of corneal thickness change as described previously [7]. Briefly, since inhibition of the Na+ pump with ouabain blocks fluid transport completely, the normal rate of fluid transport that would have existed at the time of inhibition was calculated in absolute terms as the difference between the rates of change of corneal thickness in control Ringer’s solution and after exposure to ouabain (0.5 mM). Fig. 1 exemplifies this procedure. Similarly, the rate of fluid transport in given test solutions was calculated in absolute terms as the rate of swelling in ouabain minus the rate of swelling in the test solution. Rates of swelling came from the slopes of regression lines for the first hour after exposure to test solutions. We used the Dikstein-Maurice procedure [2] for its convenience; to be noted, the rates of fluid transport obtained with it are identical to those determined by direct measurement of transendothelial fluid flow [15].

Figure 1.

Time course of stromal thickness as a function of time in control solution and after adding ouabain (100 μM). In the steady state, the stroma is dehydrated, and tends to imbibe fluid (leak). This is countered by fluid transport from stroma (basolateral) to aqueous (apical), which equals the rate of leak in the opposite direction; hence, the observed stromal thickness remains constant in control solution. Once ouabain is added, fluid transport is totally inhibited, and the stroma swells. We presume the ensuing rate of swelling (leak) equals the rate of fluid transport that would have existed before ouabain inhibition to balance the observed leak. The slope values given arise from linear regressions. Hence, the virtual rate of fluid transport (from stroma to aqueous) at the time ouabain was added is given in absolute terms by the difference between the two slopes. The error bars indicate the standard error of the mean, and are less than the size of the symbol in some cases.

All chemicals and transport inhibitors, which included ouabain, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid (NPPB), niflumic acid (NA), ethoxyzolamide (ETH) and benzamil (BZ), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Inhibitors, with the exception of ouabain, were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain stock solutions, which were then diluted into the superfusion solution to a final concentration of 0.2% DMSO.

Results

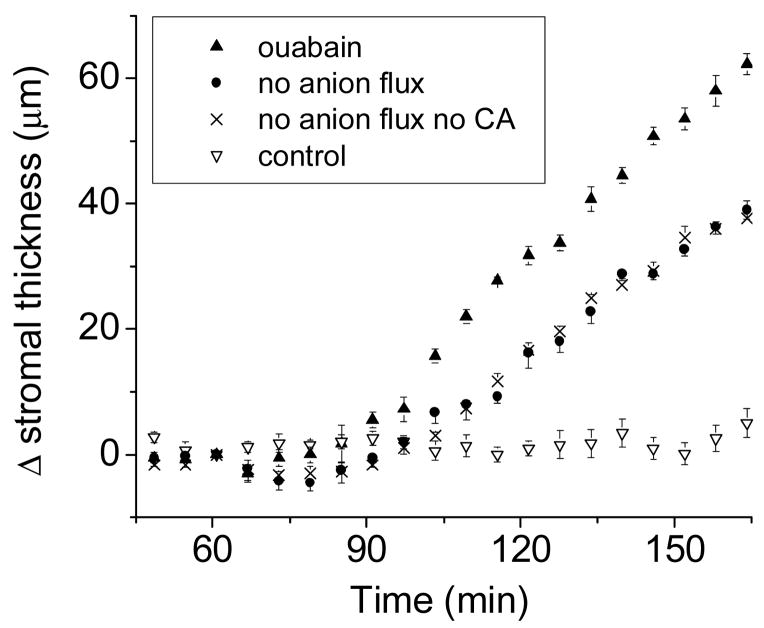

We examined how fluid transport was affected when disabling stepwise all main cellular elements that could contribute to it, including HOC3−, Cl−, and Na+ pathways, and carbonic anhydrases. Figure 2 compares several rates of change for stromal thickness, including:

Figure 2.

The considerations in the legend to Fig. 1 apply here as well. Two of the plots (ouabain, and control) have been shown in Fig. 1; they are reproduced here for comparison. For the plot labeled “no anion flux”, the preparations are in a medium without HCO3−, to which a cocktail of Cl- channel inhibitors has been added (NPPB and niflumic acid, 100 μM each). For the plot labeled “no anion flux no CA”, the solution is as the previous one except that a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, ethoxyzolamide 0.2 mM, has been added. N=4 in all cases.

very little change in control solution;

swelling in ouabain (1 mM), in which fluid transport has been cut to zero;

swelling in nominally HCO3−-free solutions containing Cl− channel inhibitors (no anion flux), and:

swelling in solution (b) plus 0.2 mM ethoxyzolamide (no anion flux, no CA activity). As the figure shows, inhibition by ouabain (solution (b) ) results in the highest rate of swelling, due to complete inhibition of fluid transport. Interestingly, using solution (c), when there is no transcellular anion flux, the inhibition of fluid transport is less than complete; in other words, there remains a considerable residual rate of fluid transport. The further addition of ethoxyzolamide (d) to solution (c) does not affect this outcome, suggesting that the residual fluid transport observed is not due to the conversion of residual or metabolically generated CO2 into HCO3−.

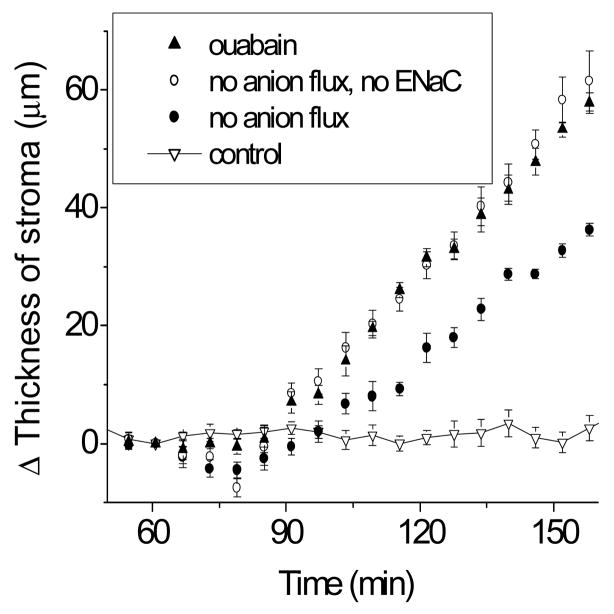

However, importantly, as Fig. 3 shows, the residual fluid transport observed above can be completely inhibited by 100 μM benzolamide, an inhibitor of epithelial sodium channels. This effect of benzolamide is dose-dependent; 10 μM benzolamide (not shown) produces a 60% inhibition of the residual fluid transport.

Figure 3.

Three of the plots in here have been shown in prior figures, namely those labeled ouabain, control, and no anion flux. For the remaining plot, an epithelial Na+ channel inhibitor, benzamil (100 μM) has been added to the solution described to result in “no anion flux”.

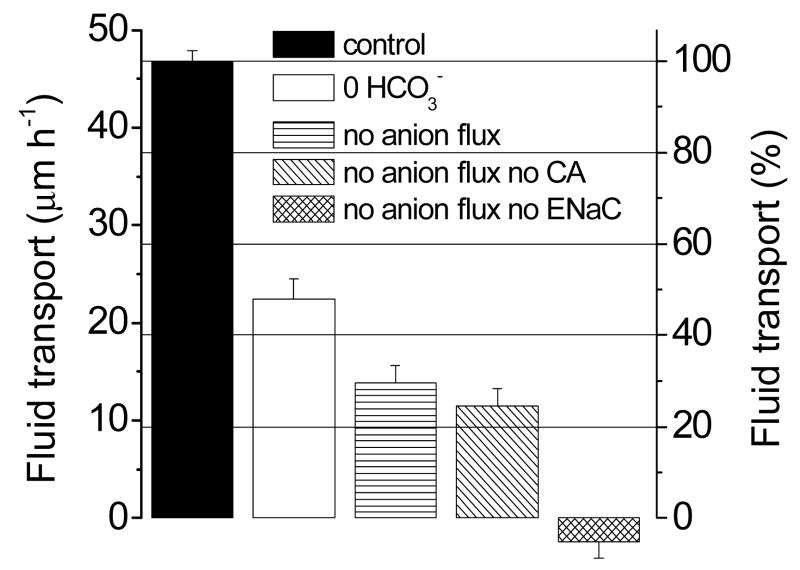

Figure 4 summarizes quantitatively these results. Column (1) serves as the control (rate of fluid transport = 100%). In nominally HCO3− free solution (column 2), fluid transport remains at 48 %; the addition of a cocktail of Cl− channel inhibitors (50 μM NPPB and 100 μM niflumic acid, column (3) leads to further inhibition but fluid transport still proceeds at 30 % of the control rate. Addition of ethoxyzolamide (column 4) does not significantly change fluid transport, as discussed further in the next paragraph. Complete inhibition of fluid movement is reached only after the addition of 100 μM benzolamide (column 5).

Figure 4.

Rates of transendothelial fluid transport from the basolateral to the apical side in control solution, and in several test solutions. Fluid transport was calculated from the rates of change of corneal thickness (cf. Fig. 1). Each bar represents the mean of four experiments. Error markers: SEM. In going from the control solution (left) to the next bar (0 HCO3−), the nominally HCO3− -free test solution results in a ~50% reduction of fluid transport. For the next bar (no anion flux), the HCO3− -free solution also contains Cl− channel inhibitors, as a result of which the fluid transport rate falls an additional ~20%. Addition of a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (label: no anion flux no CA) does not alter that rate. Only adding an epithelial sodium channel inhibitor (last bar) results in total inhibition of fluid transport.

Regarding carbonic anhydrases, in nominally HCO3− free solution there is a residual CO2 concentration which could provide the substrate for endogenous carbonic anhydrases to generate HCO3−, which in turn could be used as substrate to drive fluid transport [11, 12]. However, the results disproved this; importantly, as mentioned above, addition of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor ethoxyzolamide (0.2 mM, column 4), which inhibits both the intracellular carbonic anhydrase II and the membrane-associated apical carbonic anhydrase IV, does not affect fluid transport significantly (25% of the control rate). Therefore, the residual fluid transport observed cannot be due to hydration of intracellular CO2 to HCO3− by carbonic anhydrase and subsequent HCO3− transport as postulated earlier.

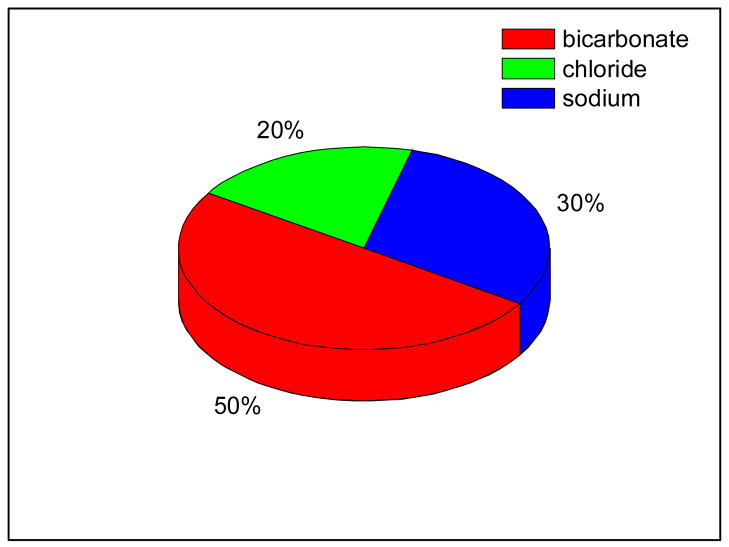

From the data presented in Figure 4 we can determine the fractions of fluid transport due to different ionic pathways. Figure 5 shows that 50% of the fluid transport is associated with HCO3− pathways, 20% is associated with Cl− and the remaining 30% with Na+.

Figure 5.

Fraction of the total fluid transport associated with each of the cellular ionic pathways (HCO3−, Cl−, and Na+) based on the information in Fig. 4.

Discussion

These data confirm that the corneal endothelium is capable of transporting fluid in nominally HCO3− free solutions [3, 10, 11]. If the transendothelial Cl− pathways are also inhibited, fluid transport still continues at 30 % of control (3rd column, Fig. 4). This residual fluid transport is not affected by carbonic anhydrase inhibition (4th column, Fig. 4), and thus cannot be fueled by the hydration of CO2 to HCO3−, contrary to earlier postulations [11, 12].

At this time there are three hypotheses regarding the mechanism of anion transport across the corneal endothelium. One of these hypotheses [6] postulates the existence of a CO2 gradient across the apical membrane. This gradient is thought to be generated by the dehydration of HCO3− by an intracellular carbonic anhydrase II and the hydration of CO2 in the space adjacent to the apical membrane by an extracellular membrane-bound carbonic anhydrase IV. In our experiments this CO2 gradient would be eliminated by the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor ethoxyzolamide and therefore this mechanism cannot explain our data. Another hypothesis assumes transport of HCO3− into the cell by an electrogenic Na+-2(HCO3−) cotransporter and its exit across the apical membrane via HCO3− conducting Cl− channels [6, 16] or non-selective anion channels [17, 18]. In our experiments extracellular HCO3− is reduced to approximately 0.169 mM or 1/200th of its normal concentration. The Na+-2(HCO3−) cotransporter reportedly has a K0.5 of 10.8 mM [19)]. Its rate of transport would be minimal under these conditions and consequently [HCO3−]i would be very low. Thus there would not be a sufficient intracellular substrate concentration to generate an anion flux of 25–30% of normal across the apical membrane. Moreover, we inhibited the carbonic anhydrases so that there cannot be an increase in [HCO3−]i due to hydration of CO2 and we also inhibited the Cl− channels to prevent any apical HCO3− efflux via these pathways. Lastly we have postulated [7] that apical HCO3− efflux is due to a Na+-HCO3− cotransporter with a Na+:HCO3− stoichiometry of 1:3. Since the intracellular HCO3− concentration is low as stated above and the K0.5 for this transporter in other tissues has been reported as 20 mM [Gross, 1998 #1896) there cannot be any significant HCO3− efflux via this mechanism either.

The observation that carbonic anhydrase inhibition does not affect fluid transport is not necessarily inconsistent with a priorly described effect of carbonic anhydrase inhibition on intracellular pH in nominally HCO3− free solutions [Bonanno, 1994 #403]. It is possible that carbonic anhydrase can raise intracellular HCO3− sufficiently above the level of 0.169 mM to affect pHi. However, in order to generate fluid transport of approximately 30% of normal, intracellular HCO3− would have to rise to millimolar concentrations. Moreover such an intracellular HCO3− concentration should alkalinize intracellular pH by almost a pH unit, and no such alkalization was found [12]. Our data thus show that significant residual transendothelial fluid transport from basolateral to apical continues in solutions with levels of CO2 and HCO3− of 1/200th of control and during inhibition of Cl− channels and carbonic anhydrases. Under these conditions the only transport of solute that remains is the transcellular movement of Na+ from apical to basolateral, entering apically via the ENaC and exiting basolaterally via the Na+ pump. To be noted, the direction of the Na+ transport (apical to basolateral) is exactly opposite to that of the residual fluid transport (basolateral to apical). The transcellular movement of Na+ is accompanied by depolarization of the apical membrane and hyperpolarization of the basolateral membrane, with a resulting transendothelial potential difference (TEPD), the basolateral side being positive. Since the junctions are cation-selective [20], this TEPD generates a paracellular current carried predominantly by Na+ ions moving from basolateral to apical, as indicated in figures 6 and 7.

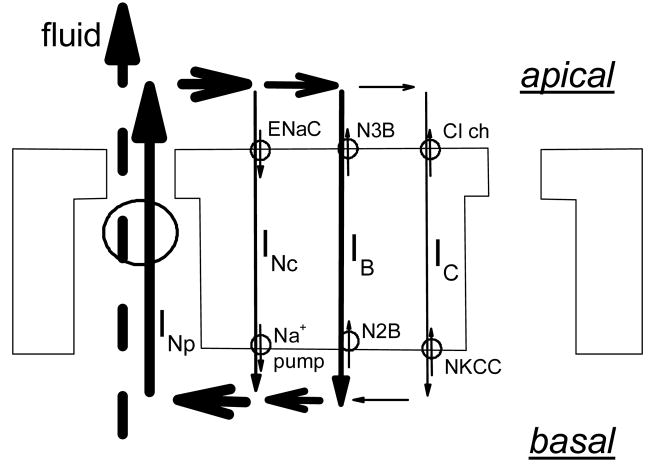

Figure 6.

Scheme of a corneal endothelial cell layer indicating how electro-osmotic coupling between the local current circulating around endothelial cells and fluid movement can explain the current results. The figure shows pathways for transcellular currents corresponding to ionic movements of Na+, HCO3−, and Cl−, namely: in the apical membrane, ENaC, a 1:3 NBC (labeled N3B), and Cl− channels; in the basolateral membrane, the Na+ pump, a 1:2 NBC (labeled N2B), and a NKCC. The total paracellular current (INp) traverses the junction, and as it reenters the cell it subdivides into three components: INc, carried by Na+, IB, by HCO3−, and IC, by Cl−. The thickness of the arrows gives a visual indication of the relative current densities. Paracellular fluid flow is shown coupled electro-osmotically to the current flow across the junction.

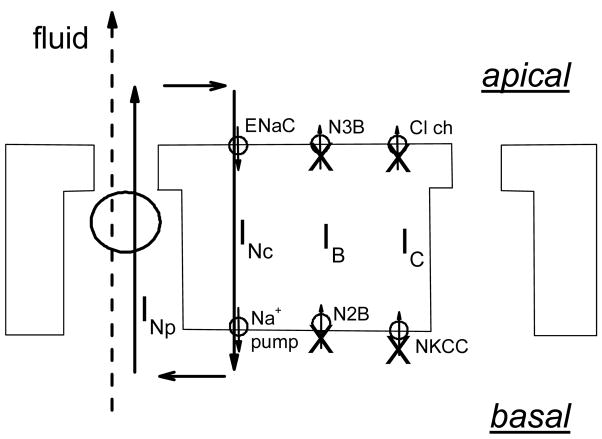

Figure 7.

As in Fig. 6, except that transcellular anion fluxes are inhibited, which leaves only the Na+ component of the recirculating current. This would result in a residual fluid transport rate generated by and corresponding to the Na+ current still circulating around the cell.

The implications for fluid transport of these two opposite Na+ fluxes (transcellular and paracellular) are as follows. The transcellular Na+ movement could somehow lead to solute accumulation in a stromal unstirred layer and thus result in an osmotic gradient. In that case the stroma would become hypertonic and transcellular osmotic fluid movement would ensue from apical to basolateral (from aqueous side to stroma). However, the fluid movement seen experimentally is in the opposite direction (Fig. 4). This then raises the question of what is the mechanism maintaining fluid transport. In this connection, we have recently shown [21] that currents passed through corneal preparations generate proportional fluid movements, and have postulated that paracellular current, generated by the transendothelial potential difference (TPD), is coupled to fluid transport via electro-osmosis, as hypothesized years ago by Lyslo et al. [22]. The scheme that we propose to explain our current data is shown in Fig. 6; in it, the total current circulating through the intercellular spaces and the junction divides in three distinct limbs as it reenters the cell, one in which the current is carried by Na+, another one by HCO3− and in the third limb by Cl−. As these three pathways can operate independently, fluid transport would result from the algebraic addition of the currents carried by each one of them. In HCO3−-free solutions with Cl− channel inhibitors, the pathway for anion current is eliminated (Figure 7), and in the presence of benzamil, the return path for Na+ recirculation is inhibited as well. Consistent with this model, there is prior evidence that inhibition of ENaC alone by phenamil or benzamil results in significant reduction of endothelial fluid transport [23].

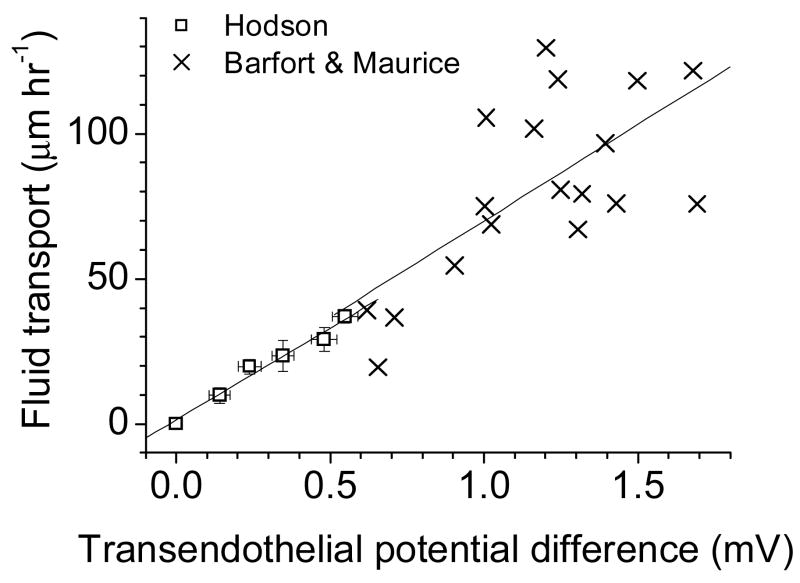

Prompted by the present data, we have re-examined earlier reports, and find that our recent proposal for electro-osmosis [21] is in fact supported by the data of Hodson [3] and Barfort and Maurice [24]. Treating their data as shown in Figure 8 yields a linear correlation between transendothelial potential difference (TPD) and fluid transport. Assuming constant specific resistance, those correlations would be between current and fluid transport. The slope is the same in both cases, suggesting identical coupling mechanisms.

Figure 8.

A correlation between transepithelial potential difference and fluid transport in rabbit corneal endothelium can now be seen after replotting data previously reported by other laboratories. We recalculated data from Barfort and Maurice [24]( Figure 2) and of Hodson [3] (Figures 3 and 5). Linear correlation fits are shown for both sets of data; the slopes are virtually identical (in μm hr−1 mV−1: Barfort & Maurice: 66.4 ± 18.1; Hodson: 63.4 ± 5.0). These earlier data are therefore consistent with our interpretation that electro-osmosis accounts for our results.

In conclusion, using our model [21], the present data can be explained in the following fashion. In nominally HCO3− free solutions there remains a TDP of 40–50 % of control [25] due to the activity of the basolateral Na+ pump. Such TPD would continue to generate a paracellular current, consisting predominantly of Na+ which, in the absence of an accompanying anion flux, recirculates via the apical ENaC and the basolateral Na+ pump. Since the Na+ recirculates, there is no net solute movement; however, due to electro-osmotic coupling, there is fluid movement. Inhibition of the apical ENaC would reduce the transendothelial potential and the recirculating current, and thus inhibit fluid transport, as observed (Figures 1 and 2). Our present data and our analysis of earlier data in the literature [3, 24] are therefore fully consistent with the model of paracellular electro-osmotic coupling of current and fluid movement in corneal endothelial cells [21] and lend further support to it. Critiques against local osmosis and a proposal for paracellular fluid transport have been advanced [26]. It would seem important to examine other leaky epithelia to determine whether paracellular electro-osmosis is a general mechanism.

Table I.

HCO3− and CO2 concentrations in control and nominally HCO3− -free solutions

| Control | HCO3− free +NPPB + Ethoxy |

|

|---|---|---|

| mM | mM | |

| [HCO3−] (medium) | 26.5 | .17 |

| [HCO3−] (cell) | ≈ 25.0 | ≈ .1 |

| [CO2] (medium) | 1.14 | .007 |

| [CO2] (cell) | 1.14 | .007 |

K0.5 for [HCO3−] of basolateral Na+-2HCO3− cotransporter= 10.6 mM [19]. Using the kinetic equations we developed [9] for this basolateral Na+-2HCO3− cotransporter, we calculate that in nominally HCO3− -free solutions the HCO3− flux across the basolateral membrane is approximately 1–2% of that in control solution.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH Grant EY06178, and by Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maurice DM. The location of the fluid pump in the cornea. J Physiol (Lond) 1972;221:43–54. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dikstein S, Maurice DM. The metabolic basis of the fluid pump in the cornea. J Physiol (Lond) 1972;221:29–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodson S. The regulation of corneal hydration by a salt pump requiring the presence of sodium and bicarbonate ions. J Physiol (Lond) 1974;236:271–302. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodson S, Miller F. The bicarbonate ion pump in the endothelium which regulates the hydration of the rabbit cornea. J Physiol (Lond) 1976;263:563–577. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuang K, Li Y, Wen Q, Wang Z, Li J, et al. Corneal endothelial NKCC: molecular identification, location, and contribution to fluid transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C491–C499. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonanno JA. Identity and regulation of ion transport mechanisms in the corneal endothelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:69–94. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diecke FP, Wen Q, Kong J, Kuang K, Fischbarg J. Immunocytochemical localization of Na+-HCO3− cotransporters in fresh and cultured bovine corneal endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:C1434–C1442. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00539.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim JJ. Na+ transport across the rabbit corneal endothelium. Curr Eye Res. 1981;1:255–8. doi: 10.3109/02713688109001856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischbarg J, Diecke FP. A mathematical model of electrolyte and fluid transport across corneal endothelium. J Membr Biol. 2005;203:41–56. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0730-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doughty MJ, Maurice DM. Bicarbonate sensitivity of rabbit corneal endothelium fluid pump in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:216–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuang K, Xu M, Koniarek JP, Fischbarg J. Effects of ambient bicarbonate, phosphate and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors on fluid transport across rabbit corneal endothelium. Exp Eye Res. 1990;50:487–493. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(90)90037-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonanno JA. Bicarbonate transport under nominally bicarbonate-free conditions in bovine corneal endothelium. Exp Eye Res. 1994;58:415–421. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klyce SD, Maurice DM. Automatic recording of corneal thickness in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol. 1976;15:550–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iserovich P, Rosensweig A, Sanchez JM, Fischbarg J. ARVO Abstract; 424, Fort Lauderdale, FL. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischbarg J, Lim JJ, Bourguet J. Adenosine stimulation of fluid transport across rabbit corneal endothelium. J Membr Biol. 1977;35:95–112. doi: 10.1007/BF01869942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Xie Q, Sun XC, Bonanno JA. Enhancement of HCO(3)(−) permeability across the apical membrane of bovine corneal endothelium by multiple signaling pathways. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1146–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rae JL, Watsky MA. Ionic channels in corneal endothelium. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C975–C989. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.4.C975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane JR, Wigham CG, Hodson SA. Sodium ion uptake into isolated plasma membrane vesicles: indirect effects of other ions. Biophys J. 1999;76:1452–6. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77305-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grichtchenko MF, II, Boron Romero WF. Extracellular HCO(3)(−) dependence of electrogenic Na/HCO(3) cotransporters cloned from salamander and rat kidney. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:533–46. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.5.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim JJ, Liebovitch LS, Fischbarg J. Ionic selectivity of the paracellular shunt path across rabbit corneal endothelium. J Membr Biol. 1983;73:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01870344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez JM, Li Y, Rubashkin A, Iserovich P, Wen Q, et al. Evidence for a Central Role for Electro-Osmosis in Fluid Transport by Corneal Endothelium. J Membr Biol. 2002;187:37–50. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyslo A, Kvernes S, Garlid K, Ratkje SK. Ionic transport across corneal endothelium. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1985;63:116–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1985.tb05228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuang K, Cragoe EJ, Fischbarg J. Proc. Alfred Benzon Symposium 34. In: Ussing HH, Fischbarg J, Sten Knudsen E, Hviid Larsen E, Willumsen NJ, editors. Water transport in leaky epithelia. Munksgaard; Copenhagen: 1993. pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barfort P, Maurice DM. Electrical potential and fluid transport across the corneal endothelium. Exp Eye Res. 1974;19:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(74)90067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischbarg J, Lim JJ. Role of cations, anions and carbonic anhydrase in fluid transport across rabbit corneal endothelium. J Physiol (Lond) 1974;241:647–675. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shachar-Hill B, Hill AE. Paracellular fluid transport by epithelia. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;215:319–50. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)15014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]