Abstract

Fc receptors (FcRs) are expressed on the surface of all types of cells of the immune system. They bind the Fc portion of immunoglobulin (Ig), thereby bridging specific antigen recognition by antibodies with cellular effector mechanisms. FcγRIIA, one of the three receptors for human IgG, is a low-affinity receptor for monomeric IgG, but binds IgG immune complexes efficiently. FcγRIIA is believed to play a major role in eliciting monocyte- and macrophage-mediated effector responses against blood-stage malaria parasites. A G → A single nucleotide polymorphism, which causes an arginine (R) to be replaced with histidine (H) at position 131, defines two allotypes which difer in their avidity for complexed human IgG2 and IgG3. Because FcγRIIA-H131 is the only FcγR allotype which interacts efficiently with human IgG2, this polymorphism may determine whether parasite-specific IgG2 may or may not elicit cooperation with cellular imune responses during blood-stage malaria infection. Here, we review data from four published case-control studies describing associations between FcγRIIA R/H131 polymorphism and malaria-related outcomes and discuss possible reasons for some incongruities found in these available results.

Keywords: Malaria, Fc receptors, polymorphism, IgG subclasses, case-control studies

INTRODUCTION

Fc receptors (FcRs) belong to the family of immunoreceptors, which includes T-cell receptors, B-cell receptors and natural killer (NK) receptors. These glycoproteins are expressed on the surface of all types of cells of the immune system; they bind the Fc portion of immunoglobulin (Ig), thereby bridging specific antigen recognition by antibodies with cellular effector mechanisms. The FcRs are essential molecules in the host defense against infection. Interaction between antibodies of a given class and the corresponding FcR elicits a variety of cellular responses, such as phagocytosis and endocytosis, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), generation of superoxide radicals and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Fleisch and Neppert, 2000). Specific FcRs are known for each class of human Ig, but FcγRI (CD64), FcγRII (CD32), FcγRIII (CD16) and FcεRI form a subset of more closely related molecules within the immunoglobulin superfamily (Kinet, 1999; Ravetch and Bolland, 2001; Monteiro and van der Winckel, 2003).

The three classes of human FcγRs comprise several isoforms (FcγRIA, -B and -C; FcγRIIA, -B and -C, and FcγRIIIA and -B), which differ in their binding affinity to different human IgG subclasses and levels of expression on different cell types. The low-affinity isoforms (FcγRIIA, -IIB, -IIC, -IIIA and -IIIB) co-localize to a region on chromosome 1q23 which includes the genes coding for C-reactive protein, a family of FcR homologues and the Duffy blood group (Su et al, 2002). Members of the FcγRII class differ from those of other FcγR classes in that they comprise either activitory (ITAM) or inhibitory (ITIM) signaling motifs within their respective ligand-binding chains (Gessner et al, 1998). FcγRIIA is a low-affinity receptor for monomeric IgG (KA <107/M), but binds IgG immune complexes efficiently. It is the most widely distributed FcγR isoform, being expressed on the surface of virtually all myeloid cells, including mononuclear phagocytes, neutrophils and platelets. This receptor plays critical roles in the removal of immune complexes, activation of inflammatory cells and phagocytosis of antibody-coated microorganisms (Ravetch and Bolland, 2001).

FcγRIIA polymorphism

FcγRIIA displays a funcionally relevant G → A single nucleotide polymorphism in the region encoding its ligand-binding domain, which causes an arginine (R) to be replaced with histidine (H) at position 131 of its extracellular domain. Both allotypes avidly bind complexed human IgG3 and IgG1, but the FcγRIIA-H131 allotype displays a higher affinity for human IgG2 and IgG3 than the FcγRIIA-R131 allotype; none of them bind IgG4 efficiently. Because FcγRIIA-H131 is the only FcγR which interacts efficiently with human IgG2, this allotype is essential for the clearance of IgG2-containing immune complexes (Salmon et al, 1996) and phagocytosis of IgG2-opsonised microorganisms (Sanders et al, 1995). As a consequence, the FcγRIIA-R/H131 polymorphism is associated with predisposition to autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome, which may be mediated by the deposition of IgG2-containing immune complexes (Karassa et al, 2004), and infections caused by encapsulated bacteria, whose clearance largely depends on IgG2-mediated phagocytosis (Rodriguez et al, 1999; Jansen et al, 1999). A second polymorphic site has been described in FcγRIIA: a CA → GA mutation results in glutamine or tryptophan in its membrane-distal Ig-like domain. This amino acid replacement, however, does not affect the receptor avidity for IgG (Warmerdam et al, 1990).

The distribution of the FcγRIIA-H131 and -R131 allotypes vary widely among ethnic groups. H131/H131 homozygotes are more frequent among Eastern Asians than Caucasians (Lehrnbecher et al, 1999), being rare in Amazonian Amerindians (Kuwano et al, 2000). Differences in allotype frequencies of FcγRIIA-H131 and other linked genes are believed to account for part of the variation in the prevalence of some autoimmune and infectious diseases among ethnic groups.

IgG subclasses and naturally acquired immunity to malaria

Malaria parasites are major human pathogens associated with 300-500 million clinical cases worldwide and 0.5-3 million deaths each year, mostly among children under the age of five years living in sub-Saharan Africa (Guerin et al, 2002). Human malaria is caused by four species of parasitic protozoa of the genus Plasmodium: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae and P. ovale. The natural history of infection with P. falciparum, that causes most severe infections and nearly all malaria-related deaths, has been well characterised in areas of high endemicity in Africa (Day and Marsh, 1991). Infants have a primary malaria attack during their first year of life, while most toddlers and juveniles have already developed tolerance against severe disease, but still experience a few clinical episodes. African adolescents and adults, in contrast, are often clinically immune; they remain free of malaria symptoms despite continuous exposure to the parasite, but maintain low-grade infections throughout the transmission season. Clinical immunity is usually lost during pregnancy, especially among primigravidae, or after migration to non-endemic areas. Life-long exposure to malaria parasites rarely leads to sterile immunity; blood-stage infections remain detectable by sensitive methods in all age groups.

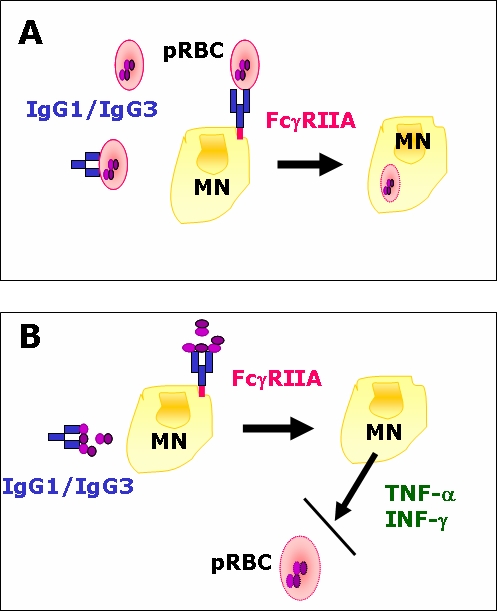

The acquisition of immunity to blood-stage malaria parasites, after several years of continuous exposure to intense transmission, depends on both antibody- and cell-mediated mechanisms. The gradual switch towards Igs of both IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses, which bind efficiently to all classes and isoforms of FcγR present on the surface of effector cells such as monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils, is believed to play a key role in this process. The binding of cytophilic antibodies to effector cells triggers parasite-killing effector responses, such as opsonisation and phagocytosis of extracellular parasites or parasitised red blood cells (pRBC) (Ferrante et al, 1990; Groux and Gysin, 1990) and the ADCC-like mechanism known as antibody-dependent cellular inhibition (ADCI) of intracellular parasites (Bouharoun-Tayoun et al, 1990) (Figure 1). Since both ADCI and the opsonising effect of cytophilic antibodies are competitively inhibited, in vitro, by non-cytophilic IgG2 and IgG4 antibodies with the same specificities (Groux and Gysin, 1990; Bouharoun-Tayoun and Druilhe, 1992), the subclass balance may be a decisive factor in naturally acquired immunity to malaria: protected and unprotected subjects could be differentiated by the relative levels of cytophilic antibodies recognising parasite antigens (Bouharoun-Tayoun and Druilhe, 1992; Ferreira et al, 1996).

Figure 1.

Antibody-dependent cellular mechanisms involved in Plasmodium falciparum blood stage killing. (A) Classical phagocytosis of parasitised red blood cells (pRBC). (B) Antibody-dependent cellular inhibition (ADCI). ADCI is an ADCC-like effect which inhibits the growth of young asexual blood-stages within erythrocytes through the release of soluble factors (such as tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-α and interferon [IFN]-γ) by monocytes (MN). This mechanism is triggered by the recognition of merozoite surface antigens by IgG, which interacts with MN via their FcγRIIA receptors. Panel B adapted from Druilhe and Pérignon (1997).

Because ADCI is known to be mediated by FcγRII (but not FcγRI) on the surface of monocytes (Bouharoun-Tayoun et al, 1995), FcγRII polymorphisms that alter the affinity of this receptor for some IgG subclasses are expected to modulate the efficiency of monocyte-mediated parasite killing. Non-immune or partially immune subjects, for example, tend to produce predominantly IgG antibodies of the IgG2 subclass during acute malaria infections (Wahlgren et al, 1983; Ferreira et al, 1996), and this subclass bias has been associated with poor clinical immunity (Bouharoun-Tayoun and Druilhe, 1992). Although often regarded as blocking antibodies (Groux and Gysin, 1990; Bouharoun-Tayoun and Druilhe, 1992), these specific IgG2 antibodies might elicit both ADCI and phagocytosis by engaging effector cells carrying the FcγRIIA-H131 allotype (Aucan et al, 2000).

More than 70% of the African-American subjects so far typed are either homozygous or heterozygous for the H131 allele (Lehrnbecher et al, 1999); quite similar H131 allele frequencies have seen found in malaria-exposed African populations (Aucan et al, 2000; Shi et al, 2001; Cooke et al, 2003; Brouwer et al, 2004). An FcγRIIA with increased affinity for human IgG2 and IgG3, in subjects carrying the H131 allele, implies that FcγRIIA-dependent parasite-killing responses might be more efficiently elicited by specific antibodies of these subclasses. Accordingly, FcγRIIA-mediated phagocytosis in vitro, following pRBC opsonisation with IgG3, is more efficient in human monocytes of the H131 allotype than in those of the R131 allotype (Tebo et al, 2002). Even more evident differences between FcγRIIA allotypes are expected in relation to IgG2-mediated protection. In fact, IgG2 antibodies to surface malarial antigens confer significant protection against blood-stage infection and clinical disease in subjects carrying the H131 allele, but not in R131/R131 homozygotes (Aucan et al, 2000). If H131 allele carriers acquire IgG2-mediated protection from blood-stage infection before the exposure-dependent switch to specific antibodies of the IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses takes place, the FcγRIIA-H131 allotype may be associated with a faster development of clinical immunity leading to reduced malaria morbidity in these subjects.

Accordingly, in a recent cross-sectional survey in Brazil we found higher levels of IgG2 subclass antibodies to locally prevalent variants of the major malaria-vaccine candidate antigen, merozoite surface protein-2 (MSP-2), among asymptomatic carriers of P. falciparum than in subjects with symptomatic malaria episodes due to the same species. Antibodies of all other IgG subclasses were found in similar concentrations in both clinical groups. Because of the high H131 allele frequency in the local population (83%), IgG2 antibodies to surface malaria antigens may help in triggering cell-mediated immunity to blood-stage parasites, via the FcγRIIA-H131 allotype, in the majority of these subjects (Scopel KKG and Braga EM, in preparation).

FcγRIIA-H131 allotype and malaria morbidity

Four published case-control studies have examined the association between H/R131 FcγRIIA polymorphism and malaria morbidity in African and East-Asian populations (Table 1). Since different malaria-related outcomes were evaluated (high-density P. falciparum parasitaemia, severe malaria in children or adolescents and adults and placental malaria) in different ethnic and age groups, these studies are not strictly comparable. Significantly, however, none of them reported an association between FcγRIIA-H131 allotype carriage and protection from malaria morbidity, as it could be expected on the basis of a putative IgG2-mediated protection against blood-stage parasites (Aucan et al, 2000). In contrast, R131/R131 homozygosity was associated with protection against high-density parasitaemia in one study (Shi et al, 2001) and H131/H131 homozygosity was associated with increased risk of either severe/cerebral malaria or placental malaria in three studies (Omi et al, 2002; Cooke et al, 2003; Brouwer et al, 2004).

Table 1.

Characteristics and main findings of four published case-control studies addressing the association between FcγRIIA polymorphism and Plasmodium falciparum malaria morbidity

| Country | Comparison groups | Main findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya | High-riska (n = 97) and low-riskb (n = 85) infants aged 1 year | Significant excess of R131/R131 homozygotes in the low risk group, when compared to H131/R131 heterozygotes; similar proportions of H131/H131 homozygotes in both groups | Shi et al, 2001 |

| Thailand | Patients aged > 13 years (mean, 25 years) with either cerebral malaria (n = 107), non cerebral severe malaria (n = 157) or mild malaria (n = 202) | Significant excess of H131/H131 homozygotes carrying the FcγRIIIB-NA2 allotypec among cerebral malaria patients, when compared to mild malaria controls | Omi et al, 2002 |

| Gambia | Children aged 0-10 years with either severe (n = 524) or mild malaria (n = 333) and non-infected controls (n = 558) | Significant excess of H131/H131 homozygotes among severe malaria patients, when compared to non-infected controls | Cooke et al, 2003 |

| Kenya | Pregnant women, either HIV-1 positive (n = 658) or not (n = 245), with (n = 285) or without (n = 618) placental malariad at delivery | Significant excess of H131/H131 homozygotes among HIV-1-positive women (but not among HIV-1-negative women) with placental malaria; similar proportions of R131/R131 homozygotes in both groups | Brouwer et al, 2004 |

High-risk infants had ≥ 30% of routine monthly blood smears positive for Plasmodium falciparum (parasite counts > 5000 parasites per microlitre) over their first year of life.

Low-risk infants had ≤ 8% of routine monthly blood smears positive for Plasmodium falciparum (parasite counts > 5000 parasites per microlitre) over their first year of life.

The FcγRIIIB-NA2 allotype reduces the capacity for phagocytosis in neutrophils, when compared to the FcγRIIIB-NA1 allotype (Salmon et al, 1990). The authors report no significant independent association between FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB allotypes and cerebral malaria; a significant association only emerged when the simultaneous carriage of H131 and NA2 alleles was considered.

Placental malaria was defined as the presence of malaria parasites in blood samples obtained, at delivery, from a shallow incision on the maternal side of the placenta.

Therefore, H131/H131 homozygosity emerged as a risk factor for malaria morbidity in three different populationss, and R131/R131 homozygosity was associated with protection from high-density parasitaemia in one population. These unexpected findings could be tentatively explained as a consequence of an increased activation of the immune system, due to the engagement of FcγRIIA-H131 by a broader repertoire of IgG subclasses, leading to the release of large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines and therefore to immunopathology and disease (Cooke et al, 2003). High frequencies of the H131 allele could have been maintained in malaria-exposed African populations as a result of a delicate balance between negative selection (due to the increased risk of severe malaria) and positive selection (due to reduced morbidity and mortality from infections with encapsulated bacteria) (Cooke et al, 2003). Alternatively, this may represent a spurious causal association resulting from linkage disequilibrium between the FcγRIIA-H131 allotype and other genetic determinants of malaria morbidity.

Further speculations are limited by the lack of more appropriate data. No longitudinal study, for example, has so far examined the combined effects of H/R131 FcγRIIA polymorphism and levels of IgG2 antibodies to malarial antigens upon malaria morbidity. Polymorphisms in other linked genes, such as FcγRIIIB, should be examined and adjusted for in risk analysis. Age represents an important factor: infants are less likely to benefit from the ability of the FcγRIIA-H131 allotype to bind malaria parasite-specific IgG2 than older children and adults, since they tend to produce low levels of antibodies of this subclass in response to antigenic stimuli (Bird et al, 1985). Adult concentrations of IgG2 are usually reached at the age of 10 years (Maguire et al, 2002), but children living in areas of intense malaria transmission are already clinically immune and rarely experience severe disease at this age (Day and Marsh, 1991). Experimental murine malaria models cannot provide valuable information, as no FcγRIIA homologue has been found in the mouse (Gessner et al, 1998).

CONCLUSIONS

Three case-control studies revealed weak but significant associations between H131/H131 homozygosity and increased P. falciparum morbidity in different populations (Omi et al, 2002; Cooke et al, 2003; Brouwer et al, 2004), while one study suggested that R131/R131 homozygosity may act as a protective factor against high-density parasitaemia (Shi et al, 2001). These results are at odds with the fact that R131 homozygotes cannot benefit from monocyte- or macrophage-mediated effector responses mediated by the binding of parasite-specific IgG2 antibodies to the H131 allotype of FcγRIIA (Aucan et al, 2000). The origins of this apparent contradiction remain unclear; the fine balance between parasite-killing and pro-inflamatory effects of cytokines released by monocytes and macrophages, as a consequence of FcγRIIA engagement by anti-parasite antibodies of different IgG subclasses, may be involved. Additional studies are clearly needed to investigate the magnitude and direction of associations between FcγRIIA polymorphism and malaria morbidity in populations differing in genetic backgrounds and levels of acquired immunity to malaria parasites.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Reseach in our laboratories has been supported by grants from the Brazilian funding agencies Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). KKGS, NTK, M da SN and MUF are recipients of scholarships from CAPES, Universidade de São Paulo, FAPESP and CNPq, respectively. We thank Estéfano Alves de Souza and Bruna de Almeida Luz (recipients of scholarships from CNPq and FAPESP, respectively) for their valuable help in data handling.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- ADCI

antibody-dependent cellular inhibition

- FcR

Fc receptor

- FcεE

receptor for immunoglobulin E Fc

- FcγR

receptor for immunoglobulin G Fc

- H

histidine

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- NK

natural killer

- pRBC

parasitised red blood cells

- R

arginine

STATEMENT OF COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declared no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Aucan C, Traoré Y, Tall F, et al. High immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) and low IgG4 levels are associated with human resistance to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1252–1258. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1252-1258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird D, Duffy S, Isaacs D, Webster AD. Reference ranges for IgG subclasses in preschool children. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:204–207. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Druilhe P. Plasmodium falciparum malaria: evidence for an isotype imbalance which may be responsible for delayed acquisition of protective immunity. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1473–1481. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1473-1481.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Attanath P, Sabchareon A, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Druilhe P. Antibodies that protect humans against Plasmodium falciparum blood stages do not on their own inhibit parasite growth and invasion in vitro, but act in cooperation with monocytes. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1633–1641. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Oeuvray C, Lunel C, Druilhe P. Mechanisms underlying the monocyte-mediated antibody-dependent killing of Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages. J Exp Med. 1995;182:409–418. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Lal AA, Mirel LB, et al. Polymorphism of Fc receptor IIa for immunoglobulin G is associated with placental malaria in HIV-1-positive women in Western Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1192–1198. doi: 10.1086/422850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke GS, Aucan C, Walley AJ, et al. Association of Fcγ receptor IIa (CD32) polymorphism with severe malaria in West Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day KP, Marsh K. Naturally acquired immunity to Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Today. 1991;7:68–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(05)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druilhe P, Pérignon JL. A hypothesis about the chronicity of malaria infection. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:353–357. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante A, Kumaratilake LM, Rzepczyk CM, Dayer J-M. Killing of Plasmodium falciparum by cytokine activated effector cells (neutrophils and macrophages) Immunol Letts. 1990;25:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(90)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MU, Kimura EAS, Souza JM, Katzin AM. The isotype composition and avidity of naturally acquired anti-Plasmodium falciparum antibodies: differential patterns in clinically immune Africans and Amazonian patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:315–323. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch BK, Neppert J. Functions of the Fc receptors for immunoglobulin G. J Clin Lab Anal. 2000;14:141–156. doi: 10.1002/1098-2825(2000)14:4<141::AID-JCLA3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner JE, Heiken H, Tamm A, Schidt RE. The IgG Fc receptor family. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:231–248. doi: 10.1007/s002770050396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groux H, Gysin J. Opsonisation as an effector mechanism in human protection against asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum: functional role of IgG subclasses. Res Immunol. 1990;141:529–542. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(90)90021-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin PJ, Olliaro P, Nosten F, et al. Malaria: current status of control, diagnosis, treatment, and a proposed agenda for research and development. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:564–573. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen WTM, Breukels MA, Snippe H, Sanders LAM, Verheul AFM, Rijkers GT. Fcγ receptor polymorphism determine the magnitude of in vitro phagocytosis of Strptococcus pneumoniae mediated by pneumococcal conjugate sera. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:888–891. doi: 10.1086/314920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karassa F, Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JPA. The role of FcγRIIA and IIIA polymorphisms in autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacol. 2004;58:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinet J-P. The high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI): from physiology to pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:931–972. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano ST, Bordin JO, Chiba AK, et al. Allelic polymorphisms of human Fcγ receptor IIa and Fcγ receptor IIIb among distinct groups in Brazil. Transfusion. 2000;40:1388–1392. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40111388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrnbecher T, Foster CB, Zhu S, et al. Variant genotypes of the low-affinity Fcγ receptors in two control populations and a review of low-affinity Fcγ receptor polymorphisms in control and disease populations. Blood. 1999;94:4220–4232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire GA, Kumararatne DS, Joyce HJ. Are there any clinical indications for measuring IgG subclasses? Ann Clin Biochem. 2002;39:374–377. doi: 10.1258/000456302760042678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro RC, van der Winkel JGJ. IgA Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:177–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omi K, Ohashi J, Patarapotikul J, et al. Fcγ receptor IIA and IIIB polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to cerebral malaria. Parasitol Int. 2002;51:361–366. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(02)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez ME, van der Pol WL, Sanders LAM, van der Winkel JGJ. Crucial role of FcγRIIa (CD32) in assessment of functional anti-Streptococcus pneumoniae antibody activity in human sera. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:423–433. doi: 10.1086/314603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon JE, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Fcγ receptor III on human neutorphils. Allelic variants have functionally distinct capacities. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI114566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon JE, Millard S, Schachter LA, et al. FcγRIIA alleles are heritable risk factors for lupus nephritis in African Americans. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1348–1354. doi: 10.1172/JCI118552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LAM, Feldman RG, Voorhorst-Ogink MM, et al. Human immunoglobulin G (IgG) FcγRIIA (CD32) polymorphism and IgG2-mediated bacterial phagocytosis by neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1995;63:73–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.73-81.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YP, Nahlen BL, Kariuki S, et al. Fcγ receptor IIa (CD32) polymorphism is associated with protection of infants against high-density Plasmodium falciparum infection. VII. Asembo Bay Cohort Project. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:107–111. doi: 10.1086/320999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su K, Wu J, Edberg JC, McKenzie SE, Kimberly RP. Genomic organisation of classical human low-affinity Fcgamma receptor genes. Genes Immun. 2002;3:S51–S56. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebo AE, Kremsner PG, Luty JF. Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in vitro. Exp Parasitol. 2002;130:300–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlgren M, Berzins K, Perlman P, Persson M. Characterisation of the humoural immune response in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. II. IgG subclass levels of anti-P. falciparum antibodies in different sera. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;54:135–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmerdam PAM, van der Winkel JG, Gosselin EJ, Capel PJ. Molecular basis for a polymorphism of human FcγRII (CD32) J Exp Med. 1990;172:19–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]