I. THEORETICAL, EMPIRICAL, AND PRACTICAL RATIONALE

A fundamental quest of the developmental social and behavioral sciences is to specify the necessary and sufficient early experiences that lead to typical human development in childhood and adulthood. Because the opportunity to experimentally manipulate early human experiences is very limited, one approach is to observe the development and long-term outcomes of children who are tragically reared in atypically deficient early environments.

Unfortunately, these studies usually are limited by a variety of confounds (J. McCall, 1999), among them sample selection, selective adoption, and the multifaceted nature of the early experience. For example, children reared in substandard orphanages (i.e., those in which some aspect of care is substantially inferior to that suggested by best practices) display developmental delays in most physical and behavioral domains, and such children who are later adopted into advantaged homes have higher frequencies of extreme behaviors and problems than nonorphanage children. But are these contemporary and long-term outcomes associated with the particular children who are sent to orphanages (e.g., unusual prenatal exposure to drugs and alcohol, adverse birth circumstances) rather than the orphanage experience per se? Which aspects (e.g., deficiencies in nutrition, medical care, toys, equipment, social–emotional neglect, lack of experience with relationships, abuse) of what is usually a globally deficient orphanage environment are associated with these delays and long-term problems?

This monograph reports a study that comes closer to validating that one attribute of the orphanage environment, namely very limited caregiver–child social–emotional interactions and the lack of opportunity to develop caregiver–child relationships, can be responsible for contemporary delays in most major domains of development in institutionalized children.

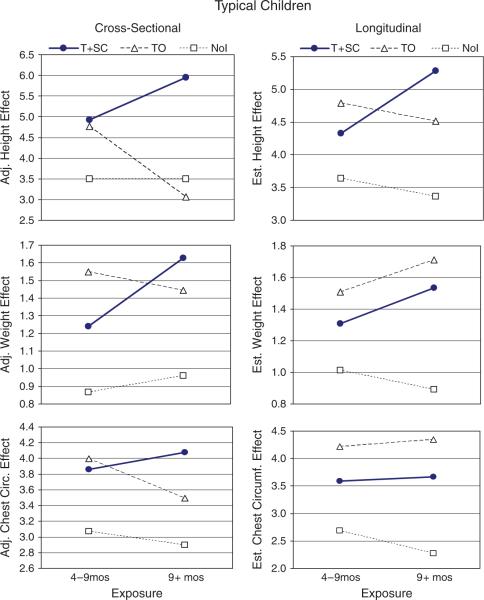

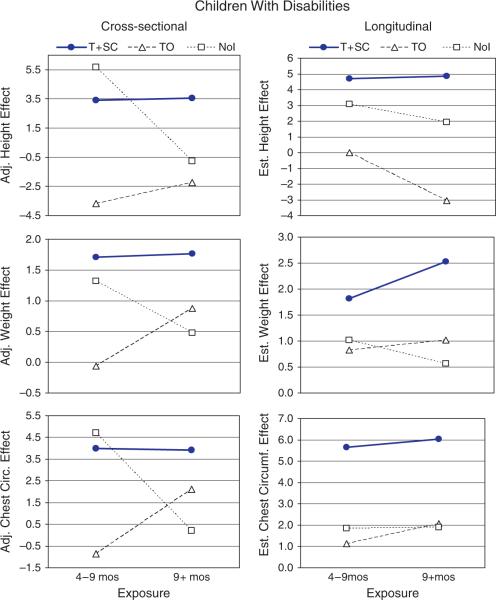

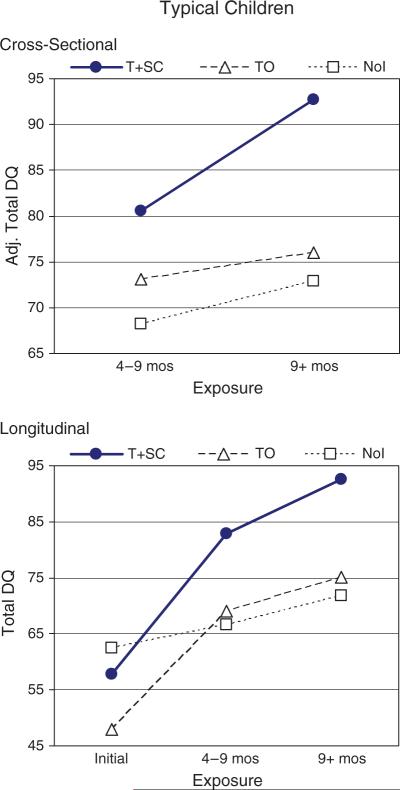

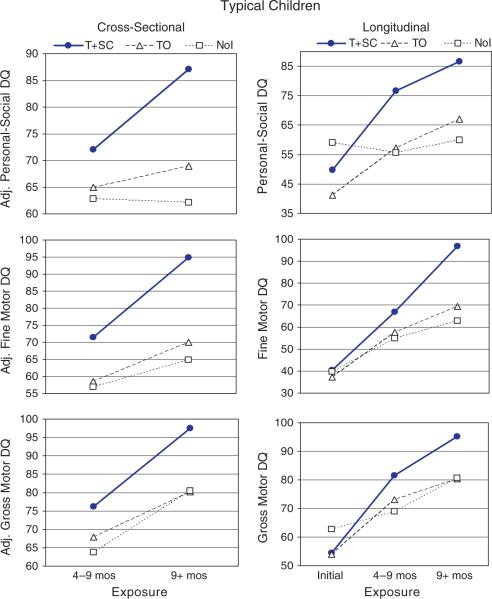

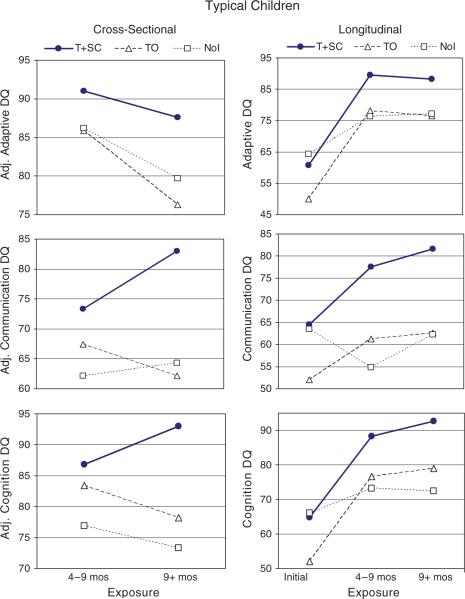

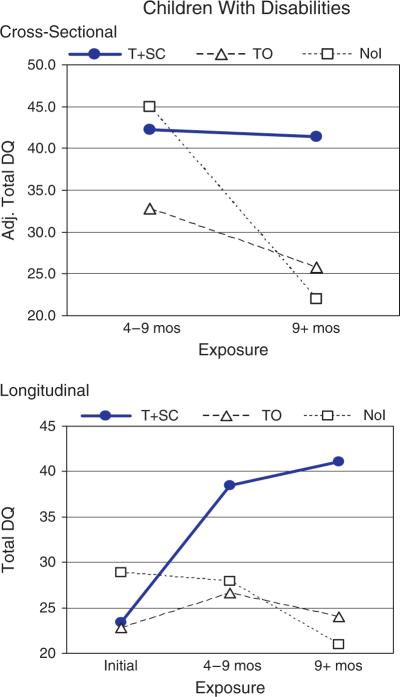

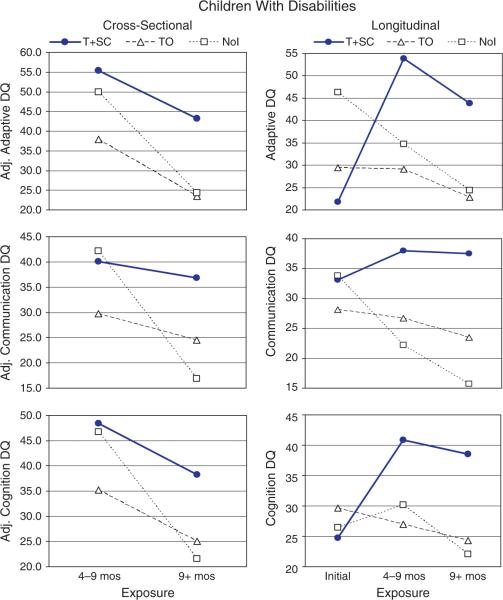

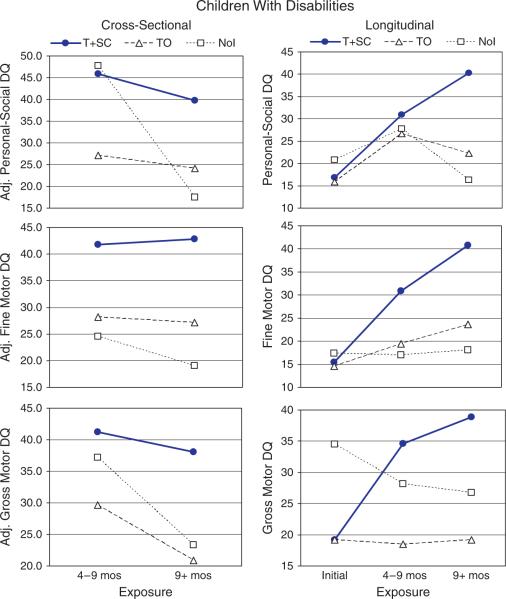

Specifically, in a quasi-experimental design, two social–emotional interventions were introduced in orphanages for children birth to 48 months in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation, that otherwise had acceptable medical care, nutrition, sanitation, toys, equipment, and the absence of abuse but were primarily deficient in the children's social–emotional experience and opportunity for adult–child relationships. The results show substantial improvement in children's physical, mental, and social–emotional development; improvements for typical children and those with a variety of disabilities; and a dose–response effect for many developmental outcomes in which the more positive social–emotional experience given to children and the longer they spent in the interventions, the greater the developmental gains. These results substantiate the potential importance of early social–emotional experience and adult–child relationships for the contemporary development of young children in institutions.

THEORETICAL RATIONALE

Most developmental theories (e.g., psychoanalytic theory, Freud, 1940; social–cultural theory, Vygotsky, 1978; social-learning theory, Bandura, 1977; attachment theory, Bowlby, 1958) emphasize the importance of early social–emotional experience and the opportunity to experience human relationships for typical social and mental development. Attachment theory, in particular, focuses specifically on early experience with a few warm, caring, and socially–emotionally responsive adults who are relatively stable in the child's life as the foundation of appropriate social–emotional development and long-term mental health (e.g., Ainsworth, 1979; Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1974; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bornstein & Tamis-LeMonda, 1989; Bowlby, 1958, 1969; Grusec & Lytton, 1988; Spitz, 1946; Sroufe, 1983; Sroufe, Carlson, Levy, & Egeland, 1999). Theoretically, an infant with a warm, responsive caregiver develops an internal working model of expectations for nurturing, supportive reactions from that caregiver, whom the infant comes to trust and use as a secure base from which to explore the social and physical world. Such experiences in turn promote the development of a sense of worthiness and self-esteem and appropriate long-term social–emotional development and mental health. Without the early experience of a few warm, caring, socially–emotionally responsive adults, long-term development may be compromised.

Meta-analyses and reviews of primarily correlational studies of home-reared children and their parents in a variety of countries substantiate several propositions that are consistent with attachment theory's emphasis on early experience with warm, sensitive, responsive adults:

Parental sensitivity (i.e., appropriate reciprocal social exchange), mutuality, synchrony, stimulation, positive attitude, and emotional support are related to secure attachment (e.g., Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003; DeWolff & Van IJzendoorn, 1997; Posada et al., 2002; van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999).

Maternal responsiveness and secure attachment in infancy predict better child social and mental skills later (e.g., Avierzer, Sagi, Resnick, & Gini, 2002; Bradley, Corwyn, Burchinal, McAdoo, & Coll, 2001; Landry, Smith, & Swank, 2006; Landry, Smith, Swank, & Miller-Loncar, 2000; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2001; Stams, Juffer, & van IJzendoorn, 2002; Steelman, Assel, Swank, Smith, & Landry, 2002).

Insecure attachment, especially when it is disorganized, is related to increased problem behaviors later. This is especially true for externalizing behaviors in males and other social, behavioral control, crime, and mental health problems, more so in high-risk children and those who continue to experience insensitive parenting and/or child care (Carlson, 1998; Crittenden, 2001; Fonagy et al., 1995, 1997; Greenberg, 1999; Greenberg, Speltz, DeKleyen, & Endriga, 1992; Lewis, Feiring, McGuffog, & Jaskir, 1984; Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, & Repacholi, 1993; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994; Shaw, Owens, Vondra, Keenan, & Winslow, 1997; Speltz, Greenberg, & DeKleyen, 1990; Stams et al., 2002).

Thus, attachment theory in particular emphasizes the important role of early caregiver–child social–emotional experience and predicts delayed development of social–emotional behavior in children lacking such experiences. Other theories (Bandura, 1977; Vygotsky, 1978) might predict delays in other domains of development, and recent reviews indicate that appropriate early social–emotional experience is crucial to a broad range of later social, emotional, and mental skills (Landry et al., 2006; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004a, 2004b; Richter, Dev Griesel, & Manegold, 2004; Set for Success, 2004), even physical development (Blizzard, 1990; Johnson, 2000a, 2000b). It is not our purpose to test one or another theory but rather to substantiate the role of early caregiver–child social–emotional-relationship experiences in the contemporary development of institutional children.

EMPIRICAL RATIONALE

Children reared in severely deficient institutional environments in numerous countries have been reported over six decades to show a variety of developmental delays.

Developmental Delays in Resident Orphanage Children

Physical Growth

Children reared in globally deficient orphanages tend to be smaller in height, weight, and head and chest circumference (e.g., Bakwin, 1949; Fried & Mayer, 1948; Smyke, Koga, Johnson, Zeanah, & the BEIP Core Group, 2004; Spitz, 1945), and children recently adopted show the same growth retardation (Benoit, Joycelyn, Moddemann, & Embree, 1996; Johnson, 2000a, 2000b, 2001; Johnson, Miller, & Iverson, 1992; Rutter, Kreppner, O'Connor, & the English Romanian Adoptions Study Team, 1998). Some investigators (Alpers, Johnson, Hostetter, Iverson, & Miller, 1997) have estimated on the basis of newly adopted orphanage children that physical growth falls behind by approximately 1 month for every 5 months children live in such orphanages. Children residing in the orphanages in this study were similarly delayed in physical development (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; see Chapter II).

The “psycho-social short stature” hypothesis (Blizzard, 1990; Johnson, 2000a, 2000b) states that children exposed to social–emotional neglect display growth deficiencies called psychosocial dwarfism (Skuse, Albanese, Stanhope, Gilmour, & Voss, 1996). It is thought growth deficiency results from hyperactivity of the corticotrophin releasing hormone-hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (CRH-HPA) axis, which reduces the growth axis both centrally (CRH increases somatastatin which inhibits growth hormone production) and peripherally (cortisol inhibits growth supporting factors from the liver; Alanese et al., 1994; Gunnar, 2001; Vazquez, Watson, & Lopez, 2000).

Unfortunately, in most studies of institutionalized children, nearly every aspect of their early environment is deficient; consequently, it is usually not possible to determine the role of their early social–emotional-relationship experiences apart from diet, nutrition, physical exercise, medical care, toys, and so forth in this growth retardation. Nevertheless, although some orphanage children are malnourished, nutrition does not seem to be the primary factor in the children's short stature. Orphanage children are often observed to eat substantial amounts of food, and their weight is consistently higher than their height, especially the weight/height index, suggesting to some investigators (Johnson, 2000a, 2000b) that psychosocial deprivation is a major cause. Further, Kim, Shin, and White-Traut (2003) randomly assigned 58 Korean orphanage infants within the first 2 weeks of life to a routine orphanage care control group or to an experimental group that received 15 min of auditory (female voice), tactile (massage), and visual (eye-to-eye contact) stimulation twice a day, 5 days a week, for 4 weeks. The stimulation was provided in a highly structured manner by research assistants who otherwise were not socially responsive to the infant. The experimental group gained significantly more in weight and had larger increases in length and head circumference immediately after the intervention and at 6 months of age. This result at least suggests that sensory and perceptual stimulation provided by human beings but not in a responsive–sensitive manner promotes physical growth.

General Behavioral Development

Children living in substandard orphanages also are markedly delayed in general behavioral development (e.g., Dennis & Najarian, 1957; Goldfarb, 1943; Hunt, Mohandessi, Ghodssi, & Akiyama, 1976; Kaler & Freeman, 1994; Kohen-Raz, 1968), and this was true for children in the orphanages in this study (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; see Chapter II). In contrast, young children reared in an orphanage that met standards of best practice developed Stanford-Binet IQs typical of the parent-reared population (Gavrin & Sacks, 1963).

Atypical Behaviors

Children living in substandard orphanages have been reported to display a variety of other atypical behaviors, including stereotyped self-stimulation, a shift from early passivity to later aggressive behavior, over-activity and distractibility, inability to form deep or genuine attachments, indiscriminate friendliness, and difficulty establishing appropriate peer relationships (e.g., Ames et al., 1997; Provence & Lipton, 1962; Sloutsky, 1997; Spitz, 1946; Tizard & Hodges, 1978; Tizard & Rees, 1974; Vorria, Rutter, Pickles, Wolkind, & Hobsbaum, 1998a, 1998b).

Over the years, it has frequently been suggested that the lack of “mothering,” appropriate social–emotional experience, and relationships with a few consistent caregivers are the primary causes of these developmental delays and deficiencies (e.g., Rutter, 2000; Spitz, 1946). While most of the early studies were on children residing in orphanages that were deficient in almost every dimension, even children who are reared in relatively good orphanages but who are subject to social and emotional neglect display many of these characteristics while living in the institution (e.g., Ernst, 1988; St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; Tizard & Hodges, 1978; Tizard & Rees, 1974).

Children Adopted From Globally Deficient Orphanages

The literature on children adopted from globally deficient orphanages spans more than 60 years, and results often appear inconsistent at best and contradictory at worst. This is not surprising given the marked variations in orphanages, measurement instruments, duration of exposure to the orphanage, and ages at adoption and assessment among other relevant parameters (Miller, 2005). Nevertheless, recent reviews (Gunnar, 2001; Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2005; MacLean, 2003; van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2006; van IJzendoorn, Juffer, & Poelhuis, 2005) discern certain common themes that demonstrate orphanage children, who are adopted typically into highly advantaged families in Europe and North America, nevertheless subsequently have higher rates of extreme behaviors and problems than non-institutionalized children, and such persistent behaviors may be related to their early orphanage experience. Specifically, these reviews indicate the following themes:

Time in the orphanage

Children adopted before 6 months rarely showed deficits or higher-than-expected rates of problem behaviors. But time in the orphanage sometimes relates to the frequency and severity of longer term delays in physical growth, mental and academic performance, internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, social and peer relations, and inattention/hyperactivity. The form of the relation between time in the orphanage and outcomes is not clear and may not be linear; that is, once a child is exposed to a substandard orphanage for more than the first 6−12 months of life, higher rates of lower levels of mental performance, attachment problems, stereotyped behaviors, and indiscriminate friendliness will be found, and longer exposure does not increase these rates. Such results may also suggest that the specific ages of approximately 6−18 months may be especially sensitive to deficiencies in orphanage environments. These results occur within studies (Gunnar, 2001; MacLean, 2003; Merz & McCall, 2007, 2008; Rutter, Beckett et al., 2007) but not always between studies (Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2005).

Temporary problems

Certain problems apparent at the time of adoption tend to be temporary, including most medical conditions, physical growth retardation, eating problems (e.g., refuses solid foods, overeats), and stereotyped or self-stimulation behaviors.

Mental performance

General mental performance tends to improve dramatically after adoption, but deficits may persist in children who spend the first several years in orphanages. Moreover, certain specific deficits may continue, and these cluster around “executive functioning,” including rigidity in thinking; inability to generalize solutions to specific problems; poor logical and sequential reasoning; excessive concreteness of thought; poor concentration, attention regulation, and inhibitory control; and restlessness and fidgeting.

Increasing problems

Certain problems may increase over the years following adoption, including internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, social and peer relations (including problems regulating emotion, anger, aggressiveness), inattention/hyperactivity, indiscriminate friendliness, and attachment problems. Attachment and behavior problems, indiscriminate friendliness, and lower IQ seem to go together in the same children. It is not clear whether such increases are related to time in the adoptive home or are associated with the children's age at assessment.

Curiously, the majority of adopted orphanage children develop typically (Gunnar, 2001; MacLean, 2003); while some circumstances are associated with increased frequencies of extreme behaviors (e.g., severe orphanage deprivations, multiple placements, time in the orphanage), it is still not possible to predict which children will and will not display persistent extreme behaviors and problems after otherwise similar orphanage experiences.

Children Adopted From Primarily Socially–Emotionally Deficient Orphanages

Only two studies followed children adopted from orphanages that were primarily deficient with respect to caregiver–child social–emotional experience (e.g., Hodges & Tizard, 1989a, 1989b; Provence & Lipton, 1962; Tizard & Hodges, 1978; Tizard & Rees, 1974, 1975). These reports, mostly based on one small sample (i.e., Tizard), reported that such children developed affectionate bonds with their adoptive parents, but were indiscriminately friendly with strangers; had higher rates of anxiety, social, emotional, and peer problems; displayed antisocial behavior at school; and had fewer close relationships than a working-class parent-reared sample. These problems were similar in type to the broader literature on children from globally deficient orphanages as well as the literature on the consequences of neglectful, psychologically unavailable parenting of children reared by their own parents (e.g., Erickson & Egeland, 2002).

Because Tizard's orphanages were relatively “stimulating” in terms of varied experiences but deficient in social–emotional relationships with caregivers, Gunnar (2001) proposed that human interaction provides early stimulation that is contingent on the child's own behavior (e.g., responsive, sensitive caregiving), which may be crucial to normal development.

Collectively, then, these studies are consistent with the hypothesis that a major contributor to contemporary delayed development and longer-term extreme behaviors and problems is the relative lack of caregiver–child warm, sensitive, responsive social–emotional interactions and the opportunity to experience relationships with a few, consistent caregivers that is typical of many substandard orphanages, and such experiences may be especially relevant between 6 and approximately 18 months of life.

The Effects of Early Interventions

Early Interventions for Parent-Reared Low-Income Children

A substantial literature demonstrates the effectiveness of early care and education programs in improving low-income, parent-reared children's development in the short-term and lowering long-term rates of school failure and certain antisocial and delinquent behaviors (e.g., Haskins, 1989; R. B. McCall, Larsen, & Ingram, 2003; Ramey & Ramey, 1992; Yoashikawa, 1995). While these interventions were primarily designed to promote children's mental development, a reanalysis of four major general intervention programs for at-risk children and those with disabilities revealed that increases in general mental and social behavior occurred only in children whose mothers increased in sensitivity and responsivity (Mahoney, Boyce, Fewell, Spiker, & Wheeden, 1998). This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that early sensitive and responsive caregiver–child social–emotional interactions and relationship experiences contribute to development in a variety of domains.

Responsive Parenting Intervention

Landry et al. (2006) recently reported an intervention in which mothers of term and very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants were randomly assigned to either a 10-home-visit training program designed to promote responsive behaviors or developmental feedback conducted when their children were 6−13 months of age. Based on the literature, responsive parenting consisted of contingent responding, emotional-affective support, support for infant foci of attention, and language input that matches developmental needs. Increased maternal responsiveness produced greater growth in social, emotional, communication, and cognitive development for both groups of infants but especially VLBW infants, a result in accord with other intervention studies for high-risk (e.g., premature, high irritability, adopted) children (e.g., Beckwith & Rodning, 1992; Juffer, Hoksbergen, Riksen-Walraven, & Kohnstamm, 1997).

Interventions in Orphanages

Several decades ago, the delayed development of orphanage children was attributed to a lack of “mothering” (Bowlby, 1958; Spitz, 1945) and/or a lack of sensorimotor stimulation, especially for very young infants (e.g., Schaffer, 1958).

Mothering Versus Stimulation

Several early studies provided orphanage infants with essentially noninteractive stimulation while others attempted to provide additional “mothering.”

Primarily noninteractive stimulation

Providing additional opportunities for tactile, visual, and auditory stimulation for several weeks produces short-term improvements in general behavioral development, or at least prevents the decline that orphanage children typically display. For example, Sayegh and Dennis (1965) placed Iranian orphanage children in a sitting position so they could watch the activities of the ward and manipulate objects; Casler (1965) had specially trained assistants provide 20 min of scheduled tactile stimulation (stroking, not vigorous massage); Hakimi-Manesh, Mojdehi, and Tashakkori (1984) had psychology students provide extra tactile, auditory (talking), and visual (eye-to-eye contact) stimulation for 5 min per day; and Brossard and Decarie (1971) provided infants with additional perceptual and/or social stimulation for 15 min daily. In each case, general developmental scores increased or did not decline relative to controls. Collectively, these studies suggest that visual, auditory, and tactile stimulation of primarily a noninteractive sort can produce gains in general behavioral development in orphanage infants within the first year of life, although the benefits tended to fade after the intervention terminated.

Social interventions

Several other studies emphasized social interactions with infants, although the extent to which these were responsive and reciprocal cannot be specified. For example, Skeels and Dye (1939) moved infants and very young children from a U.S. orphanage to an institution for mentally retarded adult females who spent time with the children teaching them eating and toilet habits as well as how to walk, talk, and play with toys. Rheingold (1956) provided 7.5 hr a day, 5 days a week of care from the experimenter herself who fed, held, talked to, diapered, and played with the children over a period of 8 weeks. More recently, Taneja et al. (2002) had professionals train caregivers how to play and interact with children (e.g., name objects, demonstrate the use of toys, talktothe children, sing songs with children) in specialized play opportunities for 90 min each day. In each of these studies, infants and children improved on general behavioral developmental assessments, although againthesegainstendedtofadewhen the interventions were terminated (Rheingold & Bayley, 1959).

More Comprehensive Social Interventions

A few interventions were more deliberately aimed at developing caregiver–child relationships by reducing the number of caregivers and making them more consistent in the lives of the children in addition to providing diverse kinds of stimulation.

Sparling, Dragomir, Ramey, and Florescu (2005) report a quasiexperimental (nonrandom assignment) and an experimental (random assignment) study conducted in 1991−1994 in a globally deficient Romanian orphanage for children birth to 3 years of age. For the intervention group, recent graduates of technical high schools were hired and trained as daily caregivers who each tended to stay with the same group of 4 children (1:4 caregiver:child ratio) over the 12-month intervention period. The comparison group used staff caregivers and had a much larger caregiver:child ratio. The intervention staff received 1 week of primarily educational training on enriched caregiving including making eye contact, pointing to objects, naming things the child sees during routine caregiving, engaging children in common events with educational value (reading a book, going for a walk, reciprocal verbal play), and implementing an individualized curriculum of educational games and interactions (adapted from Sparling, Lewis, & Ramey, 1995). Intervention caregivers received periodic additional training and frequent supervisory feedback over the 12-month intervention.

Children in the intervention group in both studies performed better on the Denver Developmental Screening Test II on personal–social, fine motor-adaptive, language, and gross motor (Study 2 only). These differences reflected the fact that the experimental group tended to make normal progress (1 month gain per 1 month in the program) while the comparison group developed at a slower-than-typical rate and progressively fell further behind. A subsample of caregivers were videotaped with children; the trained caregivers talked more than the comparison staff, and individual differences in the amount of talking was highly correlated (r = .71) with the intervention children's developmental gains.

This study demonstrates that hiring better educated caregivers, training them primarily in educational activities, creating small groups (4 children each), reducing the caregiver-to-child ratio to 1:4, and providing periodic training and supervision produces better developmental scores in young orphanage children. These intervention elements, while primarily implemented to promote mental and educational development, also provided at least the opportunity for improved social, emotional, and relationship experience.

More recently, Smyke, Dumitrescu, and Zeanah (2002) reported a small intervention in a contemporary Romanian orphanage in which “primary caregivers” were assigned to wards, the number of different caregivers serving individual children was reduced, and caregivers were encouraged to interact with the children in ways more typical of parents rearing their own children at home. This intervention, which was more deliberately focused on improving the children's social–emotional-relationship experience, produced increased child attachment ratings made by the caregivers themselves compared with children in the traditional institution. These investigators (Nelson et al., 2007; Zeanah, Smyke, & Koga, 2003) also reported that infants and toddlers from the same orphanage who did not experience the pilot intervention but were placed in foster care showed increased mental development; lower dysregulation, anxiety, and depression or withdrawal; and higher separation distress the longer they were in foster care relative to children who remained in the orphanage.

While these interventions emphasized caregiver–child interaction, presumably of a more responsive and reciprocal nature, and fewer and more consistent caregivers, the outcome measures were primarily general developmental tests (except for Zeanah et al.'s attachment and self-regulation ratings), which previous studies indicated could be improved by sensorimotor stimulation. Thus, it is not clear what the uniquely human aspect of the intervention adds, although the Zeanah et al. study suggests better social relationships. From a practical standpoint, most of these studies (except Taneja et al. and Zeanah et al.) imposed an outside intervention conducted by nonorphanage staff on the children, rather than trying to change the regular orphanage staff, behavioral culture, and structural methods of operating.

Conclusion

Collectively, this literature suggests that deficiencies in early stimulation and social–emotional experience are associated with developmental delays and increased frequency of longer term extreme behavior and problems; conversely experimental improvement in sensorimotor stimulation and educational and social interactions between caregivers and children in the context of smaller groups and fewer, more stable caregivers improves child–caregiver relationships and children's development. The current study was aimed at demonstrating the role of early caregiver–child social–emotional interactive and relationship experiences on orphanage children's development in a more direct and comprehensive manner than before by experimentally improving the social–emotional-relationship experience of orphanage children.

PRACTICAL RATIONALE

This study also is relevant to several practical issues.

Improving Orphanages

Although there are only a few orphanages in the United States, orphanages are common in the Russian Federation, East Europe, Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia. Although orphanages vary, many share certain features, especially in the Russian Federation in which there is some federal regulation over all orphanages. These similarities include caregivers having minimum social and emotional interaction with the children and thus some degree of social–emotional neglect; many and changing caregivers; large groups of children and high child:caregiver ratios; and relatively untrained staff (Rosas & McCall, 2008).

Thus, it was important to demonstrate that existing caregiving personnel and orphanage administrators could make these changes in an effective way, the changes could be sustained without additional resources once in place, and the changes could be implemented in new orphanages at relatively modest cost. Clear and broad-based demonstration of both the effectiveness of the implementation of the interventions as well as their ability to produce developmental improvements in the children would be needed to convince administrators and politicians to support similar changes in other orphanages in St. Petersburg, the Russian Federation, and elsewhere.

However, many people suggest that orphanages should not be improved but be eliminated, much as they are in the United States and Scandinavia, for example, in favor of developing a foster care system and promoting adoption. The proposition that every child should be raised in a family is a worthwhile philosophy and an ideal to be striven for, but at least in the near term it may work better in theory than in practice.

While it is possible to have high-quality and effective foster care, the foster care system in the United States, for example, generally is neither high quality nor beneficial for children (see below). Further, in much of the world, adoption is not culturally accepted or widely economically possible, so permanency planning would be limited. Also, research in the United States suggests foster parent commitment to the child is crucial to achieve beneficial outcomes for the children (Dozier, Stovall, Albus, & Bates, 2001), but not all foster parents have such commitment. Finally, even in some countries that can afford a competent foster care system (e.g., the United States), it is debatable whether they are willing to pay for it.

It took the United States nearly 40 years to get to its current, rather mediocre state, so it is likely that orphanages will exist in many countries for several decades in the future. And if they exist, it is reasonable to make them as supportive of children's development and mental health as possible, and the results of this project might provide direction and substantiation for orphanage improvements.

Nonresidential Care in Other Countries

Certainly generalizations from research conducted in residential orphanages in the Russian Federation should not be glibly made to nonresidential care and education environments in other countries, including the United States. There are many important differences between these care arrangements, including an unusual sample of children, children who do not go home to parents each night, and so forth. But there are also some similarities, and these similarities should not be ignored either.

Early Care and Education in the United States

There are several similarities between the interventions implemented in this project and circumstances pertaining to nonresidential early care and education in the United States.

First, observational studies show that major components of this project's social–emotional interventions are related to positive outcomes for U.S. parent-reared children (e.g., Landry et al., 2006) and children in U.S. child care. Children in U.S. child care become attached to their caregivers (Howes & Hamilton, 1992), especially those with whom they have a long-term, stable, consistent relationship (Anderson, Nagle, Roberts, & Smith, 1981; Barnas & Cummings, 1994) and who provide intense, responsive, and sensitive interactions (Ritchie & Howes, 2003). In turn, infants who form secure attachments with their caregivers are more advanced later in their play and peer relationships, less aggressive or withdrawn, better regulated, and more socially competent (Howes, 2000; Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994; Oppenheim, Sagi, & Lamb, 1988). Also, stability of caregiver (e.g., low staff turnover and fewer changes in care arrangements), supportive structural environments (e.g., lower child:staff ratios and smaller group sizes), and well-trained caregivers—circumstances similar to the interventions implemented in this project—are associated with children who display more on-task behaviors, improved mental and language development, and fewer peer problem behaviors (e.g., Howes & Hamilton, 1993; Kontos et al., 1995; NICHD Child Care Research Network, 1997, 2000; Peters & Pence, 1992; Whitebook, Howes, Phillips, & Pemberton, 1989). Finally, in the face of a contemporary emphasis on skill building and academic readiness, some scholars have made the case that early care and education facilities should also promote social and emotional development because it is important in its own right and because it facilitates cognitive development (e.g., Boyd et al., 2005; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004a, 2004b).

Second, relatively few nonresidential early childhood care and education facilities in the United States actually implement the structural characteristics described above that are components of the structural change intervention implemented in this study. For example, even among 22 highly selected “best practices” programs in two states, only 60% of children experienced the same caregivers all week for 1 year, only 15% had the same caregivers for more than 1 year (“looping”), and only 11% were assigned a primary caregiver (Ritchie & Howes, 2003). Relationship-building circumstances and social interaction with children may be even less common in unselected centers (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997) and home/family care (Helburn & Bergmann, 2002; Kontos et al., 1995), which serve millions of children in the United States and in other countries. Also, recent descriptions of early childhood care in Israel show it to be substantially below standard, often in ways similar to orphanage care (Koren-Karie, Sagi-Schwartz, & Egoz-Mizrachi, 2005; Sagi, Koren-Karie, Gini, Ziv, & Joels, 2002).

Third, despite the above research and “best practices,” training and licensure of early childhood care and education personnel in the United States are generally regarded as inadequate (American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, 2004; Bowman, Donovan, & Burns, 2001; Early & Winton, 2001; Morgan & Fraser, 2006), and they are especially deficient in the social–emotional aspects emphasized in the current interventions (Mehaffie et al., 2002). For example, personnel preparation in early childhood special education focuses on teaching specific teacher-directed cognitive and physical skills and tends to minimize sensitive/responsive interaction, adult–child and child–child relationships, and child-directed interactions (Rimm-Kaufman, Voorhees, Snell, & La Paro, 2003).

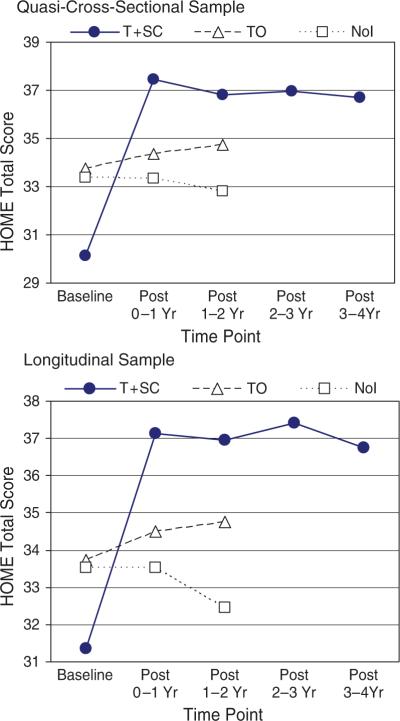

Fourth, the general quality of care in the orphanages is not much different than in some early childhood care facilities in the United States and Israel, for example. Although very deficient in certain specific social–emotional-relationship supports, the general caregiving environment as measured by the preintervention HOME Total Scores is not much lower in the orphanages in this study than in U.S. family care, and all of the score difference can be attributed to a few items that reflect the inherent nature of orphanages (Bradley, Caldwell, & Corwyn, 2003; St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005). Also, scholars and practitioners in the United States (M. Graham, personal communication, July 18, 2002) and Israel (A. Sagi, personal communication, July 18, 2002) have remarked or demonstrated empirically (Koren-Kari et al., 2005) how similar the caregiving environment in the orphanages in this study is to the child care in their projects.

Fifth, the U.S. practice literature is nearly silent on how best to improve the social–emotional environment in early care and education facilities. Specifically, training of caregivers in social–emotional development and sensitive, responsive caregiving is likely to help, but so would implementing the structural changes that promote relationship building (e.g., fewer and more permanent caregivers, looping, integration, assigning children to primary caregivers) that were the basis of the intervention in this study. Training and structural changes have not been separately manipulated in a quasiexperimental study before.

Foster Care

Other similarities can be seen with American foster care, which is “in crisis” (USGAO, 1989, 1993) even after permanency planning PL 105−89 in 1997 (Bishop et al., 2000). First, more than half of foster children stay in the system more than 3 years and experience three or more placements (Jones-Harden, 2004; Pew, 2004), resulting in many different caregivers and a lack of stable relationships similar to children in the orphanages. Second, foster parents commonly cite lack of training as a major problem (Denby, Rindfleisch, & Bean, 1999). Third, foster parents face the same dilemma as orphanage caregivers of whether to “love” the children or maintain a cool, aloof posture with minimal sensitive or responsive interactions (Heller, Smyke, & Boris, 2002). Fourth, the long-term outcomes of children in U.S. foster care are similar to children reared in substandard orphanages. They have more behavioral, emotional, school, and mental and physical health problems than children reared by biological parents, step parents, or low-income single parents (Carpenter, Clyman, Davidson, & Steiner, 2001; Kortenkamp & Ehrle, 2002), although they likely enter foster care with more problems.

Conclusion

Results from the current study cannot be generalized to nonresidential early care and education or to foster care in the Russian Federation, United States, and other countries. But demonstration of substantial positive benefits of training and structural changes in the current project could add impetus to emphasizing social–emotional relationships in the structural operation of facilities, personnel training, and support of foster and child care services in many countries.

II. BABY HOMES IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION

This chapter provides a brief history of orphanages in Russia; a description of the current orphanage system in the Russian Federation and in St. Petersburg; characteristics of the caregivers and children who were participants in this study; and a short history of this project. The intent is to provide the historical, cultural, and practical contexts that have shaped the orphanages and the current project.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ORPHANAGES IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION

The history of orphanages for children birth to approximately 4 years of age, currently called Baby Homes (BHs), in what is now the Russian Federation can be divided into three parts: The era of the czars, Soviet society, and the post-Soviet period.

Orphanages Under the Czars

Czar Fedor Alekseevich (1676−1682) established institutions that provided public care for abandoned and unwanted children similar to the large centralized institutions supported by the monarchies in Europe at the time (Ransel, 1988). In 1712, Peter the Great issued a decree calling for the establishment of hospitals for the “children of shame” funded by the czarist family and wealthy nobles.

A major shift of attitude and philosophy occurred when Ivan Betskoi wrote a decree in 1763 for the Empress Catherine II, which suggested that nurture and education homes (vospitatel'niedoma) be created rather than the more common European foundling homes or hospitals (Ransel, 1988). These new homes stressed the humanitarian goal of providing a refuge for innocent children who were born to unwed mothers or people too poor to care for their children, amid reports that some of these children were being abandoned, died, or even murdered by desperate or cruel parents. As a result, two large doma were built, one in Moscow in 1764 and the other in St. Petersburg in 1770 (Yuzhakov & Milyukov, 1904). These homes had more liberal admission policies than their counterparts in Europe, because virtually any infant or child was welcome (Ransel, 1988). Moreover, in 1767 elements of a foster care system were implemented in which rural peasant women were paid to care for children. These efforts stemmed from the Russian attitude toward humanitarian care and salvation of the child rather than the European concern for the welfare of the mother (Ransel, 1988).

Betskoi's idea of vospitatel'niedoma in which orphanage children would develop in accord with a preordained plan in a controlled institutional environment using the latest pedagogical techniques (Ransel, 1988) continued to shape Russian foundling care until the end of the czarist regime. Indeed, by the second half of the 19th century, the central Moscow dom took in 17,000 children per year and supervised more than 40,000 children at any one time, most of whom were cared for by wet nurses and foster families in the countryside around Moscow. The dom in St. Petersburg operated a similar program, receiving 9,000 infants and children each year and supervising over 30,000 children in its foster program (Yuzhakov & Milyukov, 1904). Fostering was created to handle the large number of children that needed care plus the philosophy that the mother's feeding of and constant care for the child—“mothers’ attachment to the child”—was important for the child's well-being (Rodulovich, 1892, p. 292). The biological mother herself was encouraged to feed her infant even if she was not able to otherwise care for it.

Eventually, however, the number of children needing care exceeded the capabilities of the system, the need for wet nurses and foster families outstripped the supply, epidemic illnesses threatened the health and viability of children, and an increasing number of foster families were more interested in receiving the fee than caring for children (Rashkovich, 1892).

The Soviet Period

Shortly after the 1917 revolution, the Soviet government abolished all children's and fostering institutions, which by this time had become primarily supported by foundations and charitable organizations rather than the government. Instead, a network of state-supported institutions was created. In 1918, guiding principles for the care of such children were issued that reflected the ideology of the Soviet state, which recognized that women needed to carry out their function of procreation but also were needed as laborers in the new social system that emphasized working for the state. In return, the state would help take care of children who could not be fully raised by their parents.

So a network of “mother and child homes” was created within the government's health service to support mothers who needed assistance to care for their infants and children within the context of these institutions (Konius, 1954). Later, joint placement of mothers with their infants was abandoned because of difficult economic conditions and civil war, and children were housed in the institutional homes without their mothers.

Initially, infants birth to 12 months were in one facility while children 1−3 years were in another, but soon these age groups were combined into BHs for children of single mothers, orphans who lost contact with their parents, or children whose parents lost parental rights, which was formally established by resolution in 1946. Later, such BHs also accepted children with physical and mental disabilities up to the age of 4 years. This practice persisted through the Soviet period and up to the present. For example, in 1994, 44 children with Down syndrome were born in St. Petersburg and all but 2 were sent to the BHs.

During this period, older orphans sometimes were used by criminals. Their involvement in violent and criminal activity was portrayed in newspapers and books, which contributed to society's perception of orphans, not as victims in need of help, but as outcasts and undesirable, who should be segregated from society.

Post-Soviet Period

Near the end of the Soviet and into the post-Soviet periods, intellectual opinion and social philosophy changed, but practice largely did not. For example, the Council of Ministers passed a resolution in 1988 suggesting the creation of family children's homes, a similar resolution in 1994 dictated that children without parents be fostered in rural households at the expense of the state, and the Family Code of the Russian Federation (1996) provided for placing children into a fostering family for a contract period with monetary payments for the children's support.

Philosophically, elements of the child-focused attitude and fostering system that existed in prerevolutionary Russia were present in the post-Soviet period. But the massive political, social, and economic changes and instability produced in the Russian Federation in the wake of the Soviet system did not permit the implementation of these new forms of organization. As a result, orphanages, including the BHs, are still the main institutions that care for orphaned children and those without adequately functioning parents.

CONTEMPORARY BHs

The Children

The Russian Federation

In 2004, there were 255 BHs in the Russian Federation housing approximately 19,900 children birth to 4 years of age, 15,221 were officially reported to be “delayed” in mental development and 9,953 “delayed” in physical development (Konova, 2005). Between 1993 and 2004, the total number of residents increased by approximately 12%, but the proportion of children entering the BHs during their first year of life more than doubled to 39% from 17%, presumably because of social and financial conditions.

St. Petersburg

Specifically in St. Petersburg, at the end of 2004 there were 13 BHs with a capacity of 1,195 children and 1,096 actual residents, 40.4% of whom were birth to 12 months old, 43.8% were 1−3 years old, and 15.8% were over 3 years of age. Official reports (Libova, 2005) stated that 90.6% of children were delayed mentally and 56% were delayed physically. Three fourths of the children came to the BHs from children's hospitals and 13.6% came directly from maternity hospitals.

The Staff

While much of the funding comes from the federal government, the BHs are administered by the Ministry of Health of each city and by a local district administration. While there are a variety of policies and regulations, BH directors, who are typically pediatricians, have substantial local control. Because they are under the Ministry of Health and directed by pediatricians, BHs emphasize the health and safety of children to a greater extent than their social–emotional development and mental health.

Each BH has a pediatrician director, several other pediatricians or neuropathologists, and administrative assistants. Also, each BH has specialized therapists, including “defectologists,” who have special education training (called “Special Teachers” in this monograph), and specialists in physical education, music, massage, sensory stimulation, electrotherapy, social work, and psychology.

Routine care is provided by three types of caregivers who work on the wards with the children. They include Medical Nurses, who have some medical training and are responsible for the health and welfare of the children; Assistant Teachers, who have some educational training and are responsible for the education and development of the children; and Nursery Nurses or aides who assist in routine care and activities. Although there is some variation between Homes (e.g., Sloutsky, 1997), these caregivers tend to work long hours and few days per week.

Intake and Departure of Children

Reasons for Placement

The main reasons children are sent to the BHs are (1) parental financial inability to care for a child; (2) inability of the parents to behaviorally care for the child (e.g., parental drug and alcohol abuse, mental health problems, mental and behavioral incompetency); (3) parental unwillingness to rear a child with frank disabilities; and (4) involuntary loss of parental rights because of abuse, neglect, and other inappropriate treatment. In St. Petersburg in 2004, 65% of children sent to the BHs were from single-mother families, 22.8% were placed temporarily in the BHs by their parents, 16.4% were from parents who lost parental rights, and the rest were foundlings or abandoned (Libova, 2005). From a legal standpoint, it is easier in the Russian Federation for parents to relinquish their children than in the United States, for example (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005).

Reasons for Departures

Children depart BHs at various ages and for various reasons. In 2004 in the entire Russian Federation BH system, 57.9% were adopted (a substantial increase over the 17% in 1993), nearly all internationally (only 0.9% to Russian parents), and 18% were restored to their biological families (Konova, 2005). Otherwise, children who remain in the BHs until approximately 4 years of age are transferred to “Children's Homes” within the Ministry of Education for those who do not have serious disabilities or to “Internats” under the Ministry of Labor and Social Care for those with the most severe disabilities. In 2002 in St. Petersburg, for example, 18.3% were returned to their biological families, 8% graduated to Children's Homes and 6.1% to Internats, 45.2% were adopted internationally (primarily to the United States, Germany, Scandinavia), and 14.4% were adopted by Russian parents (Libova, 2005). International adoption rates can vary substantially with political circumstances and domestic adoptions with economic conditions and region of the country.

THE BHs, CAREGIVERS, AND CHILDREN IN THE CURRENT STUDY

The current study was conducted in three BHs in St. Petersburg. They were among the five BHs in St. Petersburg that the International Assistance Group (IAG), a private Pittsburgh-based agency specializing in placing Russian children in American families, drew children to be adopted. Consequently, the three BHs used in this study were not randomly selected; rather, they were among the best in St. Petersburg, and their directors were the most cooperative with the aims and conditions of this project.

Children in the BHs

The children entering these three BHs have been described as comprehensively as any orphanage group in the literature (St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005).

Children's Birth Circumstances

Very briefly, children entering these three BHs generally represent the entire range of birth circumstances, but a substantial minority have serious perinatal complications, including higher than typical rates of low birth weight (27% <2,500 g) and very low birth weight (5.5% <1,500 g); lower average birth weight (2,798.4 g relative to a Russian Federation mean of 3,380 g); correspondingly lower average birth lengths, head circumference, and chest circumference than Russian Federation averages; and relatively lower Apgar scores (7.2 and 8.2 at birth and 10 min, respectively). Children residing in these BHs at any one point in time tend to have more adverse birth characteristics than those just arriving because of selective adoption and restoration to biological families.

Disabilities

Approximately 8% of children entering the three BHs but 21% of those in residence at any one time were considered by the current Research Team to have a disability, defined by scores on the Functional Abilities Index (Simeonsson & Bailey, 1988, 1991) that would interfere with Battelle Developmental Inventory (BDI) performance typical of this group (see Chapter IV). The most common functional disabilities pertained to physical health, mental ability, communication, and limited limb movements.

Children's Development

Children arrive at the BHs with delayed physical and behavioral development and tend to remain so. Approximately half the children in residence fall below the 10th percentile of standards for the northwestern region of the Russian Federation (St. Petersburg Pediatric Medical Academy, 2000) on height, weight, head circumference, and chest circumference, and 92−97% are below the median. Scores on the BDI relative to U.S. standardization percentiles show that children are similarly delayed at intake and while in residence. For BDI total score, 68% of residents are below the 10th percentile and 96% are below the median; children are especially delayed on the Personal–Social subscale (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005).

Departures

Over a 6-year period (1997−2002), 21% of children from these three BHs were adopted annually to the United States, 38% were adopted to other countries (mostly Scandinavia and Germany), 28% were returned to their biological parents, 7% graduated to Children's Homes, and 5% were transferred to Internats. Most adoptions (89% to the United States, 70% to other countries) and 66% of the reunifications to biological parents occurred within the first 24 months of life. Such children were likely to have nonspecific at-risk diagnoses; children graduating to Children's Homes were more likely to have fetal alcohol syndrome and Down syndrome; and those transferring to the Internats tended to have cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, hydro- and microcephalous, and so on.

Consequently, the majority of children (64% of those departing in any single year) are younger than 24 months, and because the average age of children arriving at the BHs is 6.4 months, one can estimate that slightly less than two thirds of the children reside in the BHs <18 months. Further, there is substantial selective attrition in which children with better birth circumstances and physical and mental development are more likely to be adopted or reunited with their parents before their second birthday.

The Behavioral Culture of the BHs

Generally, these BHs are acceptable with respect to medical care, nutrition, sanitation, safety, toys, and equipment and lack of physical or sexual abuse. But a behavioral “culture” exists, complemented by restrictive structural circumstances, that is characterized by minimum social and emotional interactions or relationships between caregivers and children. This culture has been comprehensively described (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005) and is similar to that reported to exist in many other orphanages. It is briefly described below with the reasons given for major elements; it is important to understand the rationale for these practices, because the interventions implemented in this project were designed to change these rationales and the entire behavioral culture of the BH.

BHs Acceptable on Most Aspects of Care

The BHs are acceptable with respect to most aspects of care. Medically, the BHs are operated under the auspices of the Ministry of Health, directed by a pediatrician, and have several physicians on staff and available throughout the day except on weekends. While caregivers have some degree of specialized training (23% receive <1 year, 48% 1−2 years), such training and continuing education tends to focus on health and safety. Children's health is monitored periodically and appropriate treatment administered within limited economic conditions. Common drugs are administered, and children are not medicated for behavioral control.

The physical environment is reasonably safe. Serious accidents, injuries, and medical errors must be reported, may be investigated, and negligent staff may be terminated. The facilities are relatively bright with many windows.

Sanitation is acceptable. The BHs are reasonably clean, and the children are bathed and cleaned regularly, although some have diaper rash.

Childrenare fed an appropriate, balanced, and nutritious diet, which was determined for this project to be adequate by international standards (Kossover, 2004). While no data exist on how much of the diet children actually eat, it is widely known that orphanage children eat substantial amounts of food (i.e., hyperphagic), and these children appeared to the authors to be no exception.

There are numerous toys available on each ward, many provided by domestic sponsors and adoption agencies including IAG, and there are a variety of learning materials, although these seem to remain on shelves and be used less frequently. Some specialized equipment for children with disabilities is available (e.g., wheel chairs, walkers), but such equipment is not used to a great extent.

While caregivers occasionally yell or physically restrain behaviorally deviant children, discipline is not frequently administered, in part because children are taught to be conforming (although a few do occasionally aggress against one another). Abuse by a caregiver is considered a very serious offense with consequences for the caregiver.

Social–Emotional Relationship Deficiencies

In contrast to the acceptable standards for most aspects of care, the extent and nature of the social and emotional interactions between caregivers and children are extremely limited and noticeably deficient, similar to many other orphanages in the literature (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005). On the one hand, the general level of care provided by the staff is not extremely deficient when measured by the HOME Inventory (institutional 24-month version; Bradley & Caldwell, 1995; Caldwell & Bradley, 1984) and compared with U.S. family child care providers (Bradley et al., 2003). BH caregivers do score significantly lower than U.S. family child care personnel on HOME total score and the subscales of Responsivity, Organization, Learning Materials, Variety, and a special Sociability index of items created for this project (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005). But the total score difference was small (2.31 points), and this deficit could be totally accounted for by certain structural aspects of the orphanage and the residential nature of the BHs. However, U.S. family child care is not a particularly enviable standard, because the quality of care across a variety of U.S. early childhood facilities is considered only “fair” (NICHD Early Child Care Network, 2000), quality is typically worse in U.S. family and home environments than in centers, and in at least some locations, the quality is getting worse as demand outstrips the availability of trained providers (Fiene et al., 2002). Moreover, the HOME consists of pass–fail items, and so the prevalence beyond yes/no of behaviors is not reflected in its score; and while items pertaining to social interactions are represented, emotions and relationships do not play a prominent role on the HOME. On individual items, BH caregivers talk and initiate activities with the children less frequently (even though they only need to talk to one of the 10−14 children once in 45 min of observation to receive credit for such an item), and they have more traditional attitudes toward childrearing that emphasize caregiver-directed rather than child-directed (i.e., responsive) interactions as reflected on the Parental Modernity Scale (NICHD, 2000; Schaefer & Edgerton, 1985) than U.S. caregivers (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005).

In contrast to the HOME results for general caregiving, specific observations in one of the orphanages document the minimum amount of caregiver–child interaction. Muhamedrahimov (1999) observed caregivers with children birth to 3 months and 3 to 10 months of age once a week from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. over a 2-month period, which hours included routine caregiving and “free time.” Across these two groups of children, caregivers initiated interaction with the children approximately 10% of the total available time (approximately 18 min). They responded to children's initiations of social interaction <1% of the time (<2 min), children cried for approximately 11 min before a caregiver responded, there was essentially no talking during more than half the time the caregivers were engaged in routine caregiving, and on average an individual child interacted with a caregiver for any reason for only approximately 12.4 min during the 3-hr period and nearly half of this was associated with feeding.

Feeding in particular represents a prime example of the lack of social–emotional interaction between caregivers and children. Infants up to 3−4 months are bottle fed, typically with no social interaction and occasionally using bottles propped on pillows. After approximately 4 months, a caregiver places the child on her lap facing laterally or directly away from her, holds the child tightly with one arm against her body while holding a large bowl of food under the child's chin, and feeds the child with a large spoon. Systematic observations showed the caregivers gave children a spoonful of food plus scraped excess food from the child's mouth twice every 5 s, and the average time to feed a child was 7.1 min with actual feeding occurring over 5.1 min. Essentially no social interaction occurs except to encourage eating or to occasionally look at the child.

Caregivers go about their caregiving duties in a business-like, perfunctory manner with little social interaction and even less emotion. Most caregivers are expressionless most of the day, and talking is as minimal during changing and bathing as it is during feeding. Most interactions with children are caregiver directed—changing and bathing are done “to” rather than “with” the child (“ready or not, here comes the water”) in assembly line fashion. Individual conformity to group standards is expected, and even dance and music activities are conducted en masse in prescribed ways often with little enthusiasm or enjoyment. Toys are frequently demonstrated to the child by the caregiver, who expects the child to imitate her action and use the toy in the “prescribed” way (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005).

Why are caregivers so socially and emotionally aloof? Much of the BH style appears to be “institutional” rather than Russian cultural. First, this characteristic is frequently reported to exist in other orphanages. Second, on a questionnaire given to a sample of 63 caregivers in one of the BHs in this study (Muhamedrahimov, 1999), 57% said that the law on BHs dictated that their main work was medical care and education, and 37% said they were unwilling to form attachment relationships with the children. Essentially all of the children leave the orphanage, many within a few months after arriving, and at least some caregivers do not want the pain of separation that might result if they form relationships with those children. Also, caregivers say they are too busy, which is true at times (e.g., when they must feed 10−14 infants in approximately an hour) but not at other times (e.g., during nap time when all children are in their cribs).

Children's Behavior

This lack of caregiver–child social–emotional interaction and relationships presumably is reflected in the children's behaviors (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005). Infants spend a great deal of time in their cribs or playpens with little to do, often engaged in stereotypic or self-stimulation behaviors (e.g., rocking, repetitive shaking of an object, head banging). Interactions with toys or other objects are simplistic, repetitive, autonomous, and rudimentary (e.g., banging, shaking, mouthing). After 6 or 8 months of age, children tend to have vacant or empty looks on their faces, relatively devoid of affect. They look at other children and strangers as if they were objects, staring blankly and examining a person as something to be explored or studied but not socially engaged.

Older children tend to play in isolation or in parallel with one another, similarly without much emotional expression. They rarely engage in sustained, reciprocal interactions of a contingent or cooperative sort with each other. They often stand or sit with nothing to do or they play with objects in the prescribed way, conforming to adult direction rather than being creative, imaginary, or experimental in their play. When strangers visit the wards, there are no displays of wariness or fear of a stranger; instead, toddlers stare and older children often are indiscriminately friendly, running up to a stranger and hugging him or her repeatedly.

Children with disabilities often receive even less attention. They are typically confined to their cribs, chairs, walkers, or playpens, often sitting or lying in contorted, asymmetric, and uncomfortable positions. Self-stimulation behaviors are very common, and these children do not seek social interaction. They tend to be lethargic, inactive, unresponsive, and display limited social–emotional expression. At some point in history, children with disabilities in most societies were not encouraged in their development and were isolated from other children, and this was especially true during the Soviet period, which emphasized group, not individual, work and accomplishment. Further, it was felt that children with disabilities would use resources, and typically developing children might learn unproductive habits if they were housed with children with disabilities. Further, there is still the medical belief, also once common in the United States, that children with disabilities are not able to improve developmentally and thus encouraging their development would be futile.

Structural Constraints on Social–Emotional Interactions and Relationships

The behavioral culture described above is promoted by a variety of employment and operational characteristics of the BHs, each of which has a rationale. As indicated above, caregivers tend to work long hours but few days per week. Such a system is not unknown in medical circles because it promotes continuity of care for sick children. In addition, BH caregivers largely prefer this system, because it allows them several consecutive days off to be with their families or to hold a second job, it minimizes transportation and meal costs that are not trivial when the salary for the job is so minimal, and salary is augmented for working night shifts. This practice, however, means that children do not see the same caregivers from one day to the next.

Children are also housed in homogeneous age groups, and then are transferred to a new set of caregivers approximately when they reach the milestones of crawling, walking, and multiword sentences. Historically, homogeneous age groups for young children were virtually unknown throughout the world's cultures until group care of young children emerged (Hartup, 1976; Konner, 1975). Homogeneous groups were created so that children could learn to socially interact with children of their own age and to provide educational experiences to children who were similar in their knowledge, language, and motor skills. The same principles that govern homogeneous educational practice after age 6 were simply applied to groups of younger children. Safety was also a consideration. Children with vastly different motor skills may hurt one another, and they can be managed more easily if they are at the same level of development and have equipment (e.g., playpens) that matches that level. But to keep groups homogeneous with respect to age and to maintain group size when children are coming and going from the BHs at various ages, “graduations” to new groups and caregivers are needed periodically. The consequence, however, is that children do not have the opportunity to have long-term relationships with a consistent set of caregivers.

Similarly, children with disabilities are also segregated, not only to provide them with specialized equipment and caregivers who are experienced in caring for such children, but as a reflection of the more general segregation of children and adults with disabilities in contemporary Russian society, just as it was some decades ago in the United States.

Common Themes in Orphanages Elsewhere

While orphanages can vary substantially in their conditions for children, several elements of the BH “culture” described above have been reported in the literature on orphanages in other European and East European countries (e.g., Groze & Ileana, 1996; Hough, 1999; Johnson et al., 1996; Kaler & Freeman, 1994; Provence & Lipton, 1962; Rosas & McCall, 2008; Sloutsky, 1997; Spitz, 1945; Tizard & Hodges, 1978; Tizard & Tizard, 1971; Vorria et al., 1998a, 1998b). Common themes across these reports include a two-room suite for housing children, many different caregivers and periodic “graduations” to new caregivers, minimum training of caregivers, caregivers who work long hours and spend little time interacting or talking with children, caregiver social–emotional detachment from children, caregiver-directed interaction, group scheduling of caretaking activities, children spending long hours in cribs or playpens often engaged in stereotypic self-stimulation behaviors, caregivers who do not respond quickly to crying, children who ignore or are indiscriminately friendly to strangers, and children who do not seem to know how to play with objects or peers (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005).

History of This Project

Background

The groundwork for this project began separately in St. Petersburg and in the United States before a collaborative project was conceived.

In St. Petersburg

Democratic changes in post-Soviet society provided a context for the St. Petersburg City Committee in 1992 to start a city-wide pilot project called “Infant Habilitation” (Kojevnikova, Chistovich, & Muhamedrahimov, 1995), which was to provide interdisciplinary aid to children from medical, biological, and social risk groups in the first months of their lives. The program emphasized working with infants and their families in a preventive manner and discouraged the common practice of parents relinquishing their children and separating children from their families. The program was to begin in one BH directed by Natalia Nikiforova and in a newly organized intervention service at a progressive child care center (Center for Inclusion) at which Rifkat Muhamedrahimov was scientific leader and assisted by Oleg Palmov, the three members of the St. Petersburg Research Team of the current project. The program was influenced by philosophical advances in Sweden (Bjorck-Akesson & Brodin, 1991), early intervention programs in the United States, and the emerging literatures on attachment, mental health in infants and young children, and caregiver–child interaction-centered programs (e.g., Ainsworth et al., 1978; Beckwith, 1990; Bowlby, 1969; Brazelton & Cramer, 1991; Crittenden, 2001; Emde, 1987; Greenspan & Wieder, 1998; Krauss & Jacobs, 1990; Osofsky, 1995; Osofsky & Connors, 1979; Stern, 1985).

In the BH, professionals started using assessments of children's development to guide educational activities and to stimulate children with severe disabilities who had previously been considered untrainable. Cooperation between the BH and the Center for Inclusion produced workshops on early social–emotional development and intervention programs as well as studies of the characteristics of the social environment of children in the BHs (e.g., Muhamedrahimov, 1999). This collaboration fostered ideas of possible ways to provide a better social–emotional environment, a more family-like environment, and more consistent caregiving in the orphanages (Muhamedrahimov, 1999; Muhamedrahimov, Palmov, & Nikiforova, 1996).

In the United States

At the same time, the IAG, a Pittsburgh adoption agency working in several BHs in St. Petersburg and elsewhere, was interested in improving the care provided to children in the orphanages. IAG sent Christina Groark, Co-Director of the University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development and a specialist in creating collaborative intervention service programs for young children, and Kathryn Rudy of the Office of Child Development to St. Petersburg in 1992 to meet with a variety of politicians as well as orphanage administrators and child development specialists, including those who would become the St. Petersburg Research Team, to explore possibilities for BH improvements.

The St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team

In 1994 Groark and Rudy were accompanied by Robert McCall, Co-Director of the University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development, to visit St. Petersburg, and in 1998 Groark and McCall plus Nikiforova, Muhamedrahimov, and Palmov collaboratively began to design specific changes in a BH that would likely improve the development of children. Long planning sessions took place at several meetings in St. Petersburg and in the United States over the next several years. Thus, the current project was designed as an international collaboration. It was not a U.S. project dropped into the orphanages of St. Petersburg or a St. Petersburg project simply in need of technical assistance; it was the result of a true partnership that required the contributions of all five of its members.

III. RESEARCH DESIGN AND INTERVENTIONS

This chapter describes the general research design and the two interventions implemented in this project.

HYPOTHESES AND UNUSUAL FEATURES

The current study was guided by several hypotheses and was unusual in numerous respects.

Hypotheses

The primary general hypothesis was:

An improved social–emotional early environment and the opportunity to develop caregiver–child relationships in the first year or two of the lives of institutionalized children will produce more advanced development in physical growth and functioning, mental and language abilities, personal–social behavior, and more mature caregiver–child interactions and social–emotional behaviors that reflect more positive relationships with caregivers. This hypothesis follows from the theoretical and empirical literature cited in Chapter I.

Several more specific hypotheses guided this work.

The early social–emotional-relationship environment can be improved through training and certain structural changes pertaining to the physical environment, employment practices, and daily procedures, and children who experienced both of these interventions will improve developmentally to a greater extent than those experiencing only training and both of these groups should be better than children having no intervention at all. As described below, training emphasized warm, sensitive, responsive caregiver–child interactions, and structural changes created an environment that promoted caregiver–child relationships; thus, the two interventions supported each other and should improve development more than training only.

The interventions were designed to promote developmentally appropriate caregiver–child interactions, and thus the longer children were exposed to the interventions, which were intended to match the child's changing developmental status, the greater the children's developmental improvement.

The interventions should benefit children with a variety of disabilities as well as typically developing children.

BASIC RESEARCH DESIGN

A quasiexperimental design was used in which two interventions and a control condition were implemented in the natural environments of three Baby Homes (BHs) for children birth to approximately 4 years of age in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation (see also Groark, Muhamedrahimov, Palmov, Nikiforova, & R. B. McCall, 2005; Muhamedrahimov, Palmov, Nikiforova, Groark, & R. B. McCall, 2004).

Between-BH Research Design and Timeline

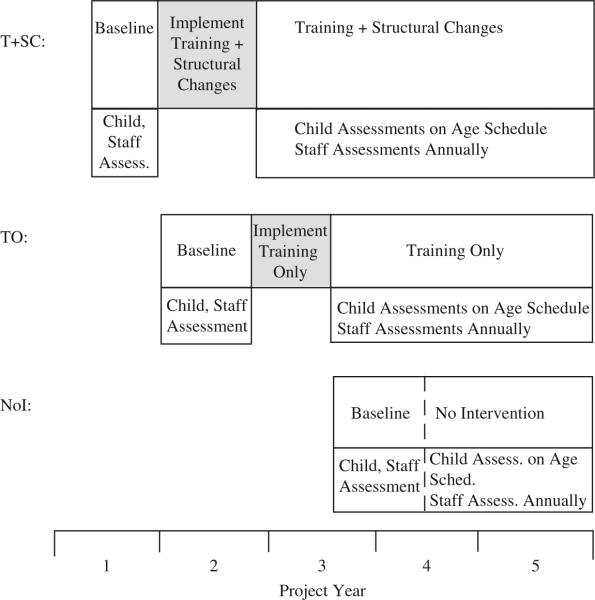

Figure 1 presents the basic between-BH research design and the timeline of interventions and assessments. Three BHs each received a different intervention condition.

Figure 1.

Design and timeline of study. Children's assessment schedule: Intake, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 months and departure.

Two types of interventions were employed (described below). Training provided caregivers with knowledge of early childhood development of typically developing children and those with disabilities and encouraged caregivers to interact with children in developmentally appropriate, warm, caring, sensitive, responsive ways, especially while performing routine caregiving duties and during play periods. Structural changes consisted of a set of physical, employment, and procedural changes designed to provide an environment more conducive to developing caregiver–child relationships by reducing group size and having fewer caregivers who were more consistently present in children's lives.

Both interventions contributed to the overriding goal of changing the “institutional” behavioral culture characterized by aloof, perfunctory caregiving conducted impersonally in large groups by many changing caregivers to an atmosphere that was more typical of warm, sensitive, responsive “parent–child” interactions conducted in a more “family-like” set of circumstances. The interventions, each based on a research literature, focused more on attitudes and behavioral styles (e.g., be responsive, talk, interact, be warm and caring, display emotions and feelings, develop relationships) coupled with knowledge of children's behavioral development that each caregiver would carry out in her own way and adapt to different situations and different ages of children, rather than a set of specific behavioral actions, activities, or organized programs of activities that would be carried out according to an established schedule. Although a main purpose was to partially separate the effects of training only from training coupled with structural changes, we expected the two interventions to complement and synergize each other. Further, the literature on attachment and the development of children adopted from institutions, for example, suggests that this new behavioral culture should be most influential in children's lives between approximately 6 and 18−24 months of age, and most orphanage children spend at least part of this interval in residence.

Training Plus Structural Changes