Abstract

Objectives

Vascular access dysfunction is a major problem in hemodialysis patients, only 50% of arteriovenous grafts (AVG) will remain patent 1 year after surgery. AVG frequently develop stenoses and occlusions at the venous anastomoses, in the venous outflow tract. Lumen diameter is determined not only by intimal thickening but is also influenced by remodeling of the vessel wall. Vascular remodeling requires degradation and reorganization of the extracellular matrix by the degradation enzymes, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). In this study, we aimed to provide further insight into the mechanism of endothelial regulation of vascular remodeling and luminal narrowing in AVG.

Methods

End-to-side carotid artery-jugular vein polytetrafluoroethylene grafts were created in twenty domestic swine. The anastomoses and outflow vein were treated with Gelfoam® matrices containing allogeneic porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAE, n=10) or control matrices without cells (n=10) and the biological responses to PAE implants investigated 3 and 28-days postoperatively. Pre-sacrifice angiograms were evaluated in comparison to baseline angiograms. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin, Verhoeff’s elastin as well and antibodies specific to MMP-9 and MMP-2 and subjected to histopathological, morphometric and immunohistochemical analysis.

Results

Veins treated with PAE implants had a 2.8-fold increase in venous lumen diameter compared to baseline (P<.05), a 2.3-fold increase in lumen diameter compared to control and an 81% decrease in stenosis (P<.05) compared to control at 28-days. The increase in lumen diameter by angiographic analysis correlated with morphometric analysis of tissue sections. PAE implants increased venous lumen area 2.3 fold (P < .05), decreased venous luminal occlusion 66%, and increased positive venous remodeling 1.9 fold (P< .05) compared to control at 28-days. PAE implants reduced MMP-2 expression at 3 and 28 days, neovascularization at 3 and 28-days and adventitial fibrosis at 28-days, suggesting a role of the implants in controlling the affects of medial and adventitial cells in the response to vascular injury.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that the adventitial application of endothelial implants significantly reduced MMP-2 expression within the venous wall, increased venous lumen diameter and positive remodeling in a porcine arteriovenous graft model. Adventitial endothelial implants may be useful in decreasing luminal narrowing in a clinical setting.

Clinical Relevance

Vascular access dysfunction is the leading cause of hospitalization and morbidity in patients receiving hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease. Data indicate that the majority of AVG fail due to the formation of stenosis at the vein-graft anastomotic and venous outflow sites. The stenoses result in luminal narrowing and subsequent graft thrombosis and failure. A satisfactory long term pharmacologic means of preventing stenosis due to intimal hyperplasia in hemodialysis grafts has yet to be found. In a large animal model of AVG we show that placement of an adventitial endothelial implant significantly increased venous lumen diameter at 28-days.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular access failure is the major complication in providing care to patients on hemodialysis therapy.1 Although an autogenous fistula is the recommended method to obtain vascular access, AVG are still a predominant type of access used in the United States, especially for those patients with a previously failed fistula. AVG created for vascular access have a primary patency rate of only 50% at one year,1, 2 with 80% of these failures arising from graft thrombosis.3 This pathological failure mode frequently arises from progressive intimal hyperplasia and constrictive remodeling, which occludes the lumen of the venous anastomotic and outflow sites and culminates in graft thrombosis.4 The current therapy for AVG stenosis is either surgical revision or angioplasty with or without stenting.5, 6 Luminal loss due to the formation of intimal hyperplasia has been attributed to smooth muscle cell (SMC) migration from the media into the intima in combination with platelet and leukocyte activation and subsequent extracellular matrix deposition at the lumen side. However, it has recently become evident that adventitial thickening, fibrosis, inflammation and neovascularization also contribute to lesion formation, negative remodeling and lumen loss after experimental vascular injury.7–10 In this paradigm, vascular injury elicits a cascade that begins with the proliferation of adventitial fibroblasts, their differentiation into myofibroblasts, secretion and activation of MMPs and cell migration from the adventitia and media to the intima. The adventitia is therefore a potential therapeutic target for AVG failure. Placement of allogeneic endothelial implants onto the adventitial surfaces of injured vessels effectively diminished intimal thickening after angioplasty and the creation of AV fistulae.11–13

In the present study, we investigated the vascular responses to injury at the lumen, media and adventitia of AVG treated with perivascular allogeneic endothelial implants. We hypothesized that placement of endothelial implants, shown to produce normal endothelial inhibitory compounds in vitro, onto the adventitia of venous anastomotic and outflow sites could increase positive, or expansive, venous remodeling and decrease luminal narrowing. We now report that the application of endothelial implants to the adventitia of AVG significantly reduced angiographic vascular stenoses and increased histologic measures of venous lumen and total vessel areas 28-days after surgery. Furthermore, endothelial implants also reduced MMP-2 expression, adventitial fibrosis and neovascularization compared to control.

METHODS

Formulation and Testing of Endothelial Implants

PAE (Cell Applications, San Diego, CA) were cultured and maintained in Gelfoam® matrices as previously described.11 4.0 × 1.0 × 0.3 cm3 blocks of sterile Gelfoam® (Pfizer) were seeded with 1.25 –1.66 × 105 cells/cm3 of Gelfoam® and incubated for ≈ 2 weeks until confluent in Endothelial Basal Media (Lonza, Portsmouth, NH) supplemented with 5% FBS and 50 μg/mL gentamicin. Confluence was determined by periodic evaluation of cell number after enzymatic digestion.11 PAE were implanted post-confluent. The production of heparan sulfate (HS), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), nitric oxide (NO), tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, by PAE cultured in Gelfoam® matrices were used as markers of cell function. HS levels in conditioned media were determined using a dimethylmethylene blue binding assay. TGF-β1, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 concentrations were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Total NO levels were determined indirectly in an ELISA assay (R&D Systems) based on the Greiss Reaction. Control Gelfoam® matrices, which did not contain cells, were incubated for up to 2 weeks in medium containing 5% FBS prior to implantation.

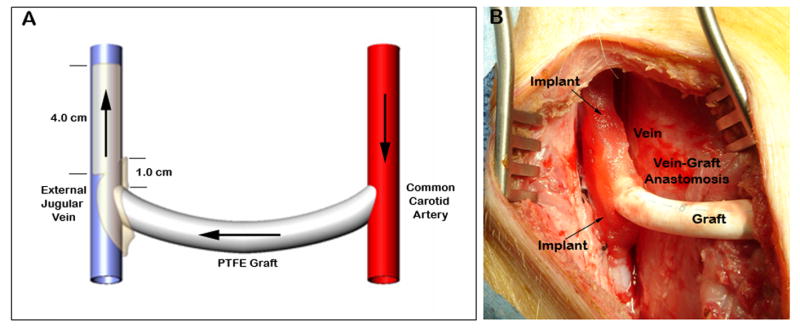

Placement of Arteriovenous Grafts

The ability of the endothelial implants to reduce stenosis and lumen loss when wrapped around AVG was assessed in an established porcine AVG model.14 This study conformed to the United States Department of Agriculture regulations and National Research Council guidelines and to the guidelines specified in the National Institutes of Health “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Duke University Medical Center (Durham, NC) approved the study. Twenty male and female domestic Yorkshire pigs, 34 kg ± 0.9 kg and ≈ 10–12 weeks of age, were obtained from Wesley Looper Farm (Hickory, NC). Animals received 650 mg aspirin 48 and 24 hours prior to surgery and 325 mg daily until the end of the study. All animals received dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg, IV) prior to surgery to minimize inflammation in the neck. Anesthesia was induced (Telazol, 4.4 mg/kg Ketamine, 2.2 mg/kg, Glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg/ml, Acepromazine maelate 10 mg/ml and Thiopental 2.5%, 0.22 ml/kg), the pigs were intubated and anesthesia maintained with isofluorane inhalant (0.5 – 2%) delivered through a volume-regulated ventilator. Intravenous heparin was administered prior to graft surgery as a 100 U/kg bolus. Additional bolus doses of heparin were administered as necessary to maintain activated coagulation time (ACT) ≥ 200 seconds. All pigs received intramuscular buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg) immediately after surgery. Bilateral 8-cm neck incisions were made over the sternocleidomastoid muscle on each side of the neck. A 6-mm internal diameter PTFE graft (Atrium Medical Corp, Hudson, NH) was tunneled in a subcutaneous tract between the two incisions (the average length of graft was 18.6 ± 0.9 cm). Oblique end-to-side anastomoses were made between the jugular vein and graft and the carotid artery and graft using 6-0 prolene suture. Following completion of the anastomoses, the graft was percutaneously cannulated just distal to the carotid artery-graft anastomosis. The venous anastomosis and outflow tract were imaged using an OEC 9600 C-arm fluoroscope in two planes with 90 degree offsets (10–15 cc’s Renograffin, full strength). The anastomoses were then wrapped with two Gelfoam® matrices containing PAE (n=10) or no cells (n=10), covering ≈ 0.5-cm of graft and vein equally (Fig 1). Each proximal venous segment was also treated with one matrix containing PAE or no cells by placing the matrix longitudinally along the length of the vein starting at the anastomotic site (Fig 1), thereby covering an additional 3–4-cm of outflow vein. Gelfoam is an approved gelatin-based surgical sponge that is commonly used in vascular access procedures as an adjunct to hemostasis. Gelfoam causes little cellular infiltration and is generally left in place and the wound closed over it. Empty Gelfoam matrices were used as the control vehicle in this study.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of AVG and venous implant positioning, arrows indicate direction of blood flow. (B) Photograph after implantation of three PAE/Gelfoam® matrices at the venous site immediately after AVG creation.

Graft patency was confirmed weekly throughout the study by Doppler ultrasound. On the 3rd and 28th post-operative days animals were euthanized with intravenous sodium pentobarbital and the graft and associated vessels perfusion fixed in situ with PBS followed by Formalin. Cine angiography was performed prior to sacrifice as described above. Percent stenosis was calculated quantitatively for patent grafts by measuring the lumen diameter of the graft (LGD) distal to the arterial anastomosis and the lumen diameter at the venous anastomosis (LVD). Three measurements were made at each location and averaged. The percent stenosis was determined at implant (day 0) and at sacrifice using the following equation: . Venous lumen diameter was determined by taking the average of 3–4 measurements starting just distal from the anastomotic site and along ≈ 6-cm length of vein. The average venous lumen diameter (VLD) for each image was normalized by the corresponding LGD for that image. Late venous luminal gain (VLG) was determined by comparison of the venous lumen diameter post-surgery (VLDday0) to that just prior to sacrifice (VLDsac). Luminal gain was calculated by dividing each venous diameter by the reference graft diameter (LGD) using the following equation: . Data from orthogonal images were averaged so that each animal resulted in one data point for each analysis.

Tissue Processing and Staining

The anastomotic sites and surrounding tissue were trimmed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, mounted on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Three 5-μm sections were obtained through each arterial anastomosis at 1-mm intervals and also across each venous anastomosis. After the last venous anastomotic section, five sections through the venous outflow tract at 2–3 mm were obtained over an additional length of 15 mm of vein. Slides were read and interpreted by a Board-certified Veterinary Pathologist blinded as to treatment groups. Histomorphologic findings were graded on a scale from 1 through 4, depending upon severity (0 = no significant changes; 1 = minimal; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe, Appendix – Table 1). Histomorphometric analysis was performed on Verhoeff’s stained sections from the arterial and venous sites of patent grafts from animals euthanized at 28-days. The intimal (I), medial (M) and lumen (L) areas were measured using computerized digital planimetry with an Olympus BX51 microscope, an Olympus DP-70 digital camera and customized software. The boundaries of each layer (lumen, intima and media) were outlined and the computer software determined the area (mm2) within each outlined sector. In anastomotic sections which contained both vessel and graft, the vessel and graft were measured separately. Morphometric measurements were made by a Board-certified Veterinary Pathologist that was blinded to the treatment groups. The extent of luminal occlusion and intimal hyperplasia was determined by normalizing the intimal area by the lumen [I/(I+L)] or media area [I/(I+M)], respectively. Total vessel size and the extent of remodeling were assessed by measuring the area circumscribed by the outer border of the external elastic lamina (EEL) of the vessel.

MMP expression was localized in venous sections using antibodies specific for the precursor (pro) and activated forms of MMP-2 and -9 (murine anti-human MMP-2 or rabbit anti-human MMP-9 1:250 dilution, Chemicon International, Inc., Ternecula, CA). For every specimen, at least six non-overlapping fields were analyzed per section. For quantitative assessment of positive MMP staining, randomly selected areas were imaged using an Olympus BX60 microscope. Digital images were captured and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Each area of interest was highlighted and positive staining quantified by color segmentation. The results were expressed as percent positive area (positive area in mm2 over total area in mm2). Quantitative assessment of positive staining was performed by an observer that was blinded to the treatment groups.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis comparing treatment groups used a non-parametric Mann -Whitney test performed using GraphPad Prism version 3.02 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California. A Pearson correlation determined the relationship between lumen diameter and MMP expression. Values of P<.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Biological Effects of Perivascular Endothelial Implants

The number of PAE that could be recovered from Gelfoam® matrices increased exponentially from 1.25 – 1.66 × 105 cells/cm3 on day 0 to 10–16 × 105 cells/cm3 at confluence. PAE/Gelfoam® matrices were assayed for TGF-β1, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, NO and HS production. Significant levels of HS (1.33 ± 0.23 μg/mL/day), TGF-β1 (507 ± 22 pg/mL/day), NO (2.1 ± 0.40 μmol/L/day) and TIMP-2 (9.3 ± 0.96 ng/mL/day) were detected in conditioned media collected from post-confluent in vitro cohorts. These levels are similar to that produced from cells grown on tissue culture polystyrene (data not shown). TIMP-1 was not detected in conditioned media samples.

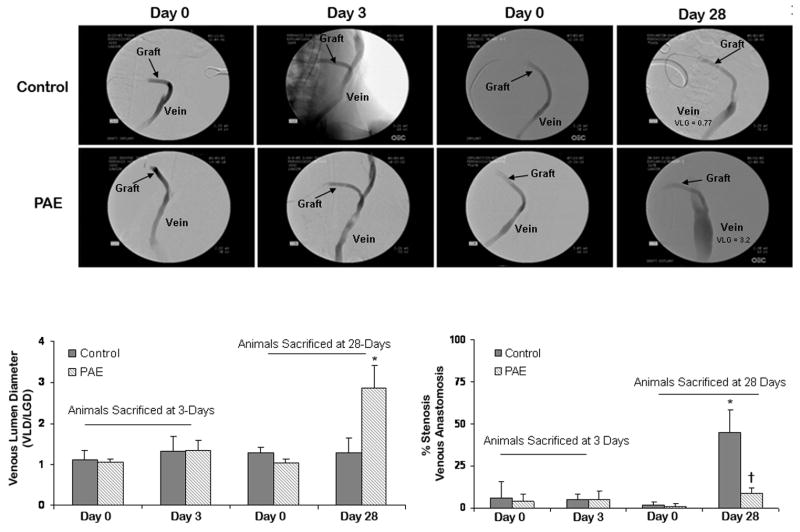

The pigs used in this study were randomly selected to receive one of the following treatments: PAE/Gelfoam® or Gelfoam® without cells. Animals were euthanized at 3 (n=5 Gelfoam® control, n=5 PAE/Gelfoam®) and 28-days (n=5 Gelfoam® control, n=5 PAE/Gelfoam®). All incisions healed well and all animals gained weight throughout the respective post-operative period. Two control grafts and one PAE treated graft were occluded at the 3 day sacrifice. One control and one treated graft were occluded at the 28-day sacrifice. All occlusions occurred early (within the first 7 days) and were not unexpected in this model. Analysis of angiograms of patent grafts obtained at baseline and sacrifice revealed an increase in VLG at day 28 for PAE treated veins when compared to control (1.8 ± 0.58 vs. 0.01 ± 0.44, respectively). The treated veins increased 2.8-fold in diameter from 1.04 ± 0.09 at day 0 to 2.9 ± 0.56 at day 28 (P <.05) while control veins remained essentially unchanged from 1.28 ± 0.13 at day 0 to 1.29 ± 0.35 at day 28 (Fig 2). Veins treated with PAE implants had a 2.3-fold increase in VLD when compared to control, which appeared to extend over the 4-cm length covered by the implant and up to 2-cm beyond. No significant VLG was observed in control or PAE treated animals at 3 days. The cell-containing implants also reduced vein-graft stenosis by 81% from 45 ± 13 % for control grafts to 8.5 ± 2.9 % for PAE treated grafts (P<.05) at day 28. Morphometric analysis of the vein at the anastomotic and outflow sites (Table I) demonstrated similar results. Veins treated with cell-containing implants had a 2.3 fold increase in lumen area compared to control (P<.05). In addition, total vessel area increased from 11.16 ± 3.4 mm2 for control to 20.72 ± 2.6 mm2 for PAE treated veins (P<.05) suggesting greater positive remodeling in the treated veins. PAE/Gelfoam® also reduced venous luminal occlusion by 66% and intimal thickening by 51% (Table I). Morphometric analysis of graft sections at the venous anastomotic site revealed little differences in pseudointima (2.45 ± 0.23 and 2.23 ± 0.14) or lumen areas (11.64 ± 5.7 and 13.2 ± 2.6) between control and PAE implants, respectively, suggesting that the majority of the benefits were localized to the native vessel. At four weeks post-implant, there was minimal stenosis and luminal occlusion observed at the arterial sites and no obvious differences in vessel remodeling between groups (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Representative angiograms and measurements. (A) Baseline angiograms of control and treated grafts show no significant changes in venous diameter or % stenosis three days after surgery. Comparison of angiograms obtained 28-days after surgery compared to baseline show greater VLG in PAE treated veins and less stenosis at the venous anastomotic site compared to control. (B) Bar graph of changes in venous lumen diameter 3 and 28-days post-surgery. (C) Bar graph of the average percent stenosis 3 and 28-days post-surgery. *P< .05 compared to day 0, †P< .05 compared to control at the same time point.

Table I.

Histopathological Characteristics of Venous Sites at 28-days

| Characteristics | Control | PAE |

|---|---|---|

| Intima Area (mm2) | 1.3 ± 1.04 | 0.88 ± 0.30 |

| Media Area (mm2) | 4.04 ± 0.69 | 6.66 ± 2.37 |

| Lumen Area (mm2) | 5.82 ± 1.38 | 13.18 ± 2.74* |

| EEL Area (mm2) | 11.16 ± 1.97 | 20.72 ± 1.51* |

| Luminal Occlusion (ratio)† | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.06± 0.02 |

| Intimal Thickening (ratio)‡ | 0.24 ± 0.16 | 0.12 ± 0.08 |

P<.05 compared to control

Measurements were averaged so that each animal resulted in 1 data point.

Luminal Occlusion= I/(L+I)

Intimal Thickening = I/(I+M)

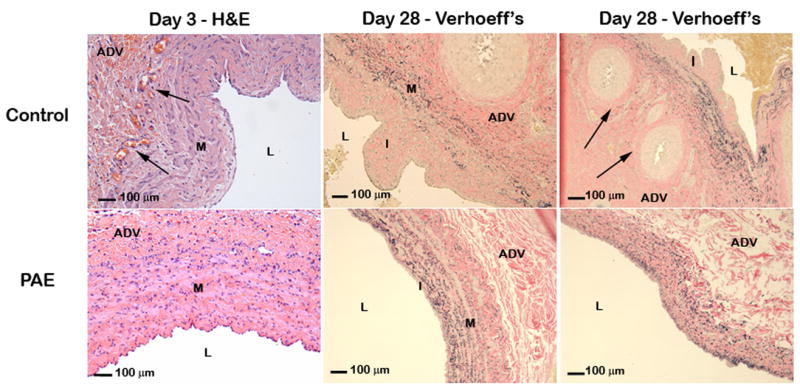

Minimal inflammation was present in the adventitia of the venous implant sites in animals from both groups at 3 and 28-days with no significant differences between control and PAE treated anastomoses (Table II). Fibrosis was also present in the adventitia of veins in animals from both groups at 3 and 28-days, with an increase in fibrosis at 1-month consistent with the healing process. Less fibrosis was noted in PAE-treated veins compared to veins in control animals at 28-days (Table II). Evidence of neovascularization was also observed in both groups at both time points. Both acute and chronic neovascularization was decreased in PAE treated veins when compared to control (Table II, Fig 3). No significant circumferential variation was seen in any of the sections analyzed for histomorphology or histopathology. None to minimal luminal inflammation was observed at the acute and chronic time points in this model and no difference observed between groups (data not shown).

Table II.

Severity of Inflammation, Fibrosis and Neovascularization at the Adventitial Venous Sites

| Inflammation1 | Fibroblasts/Fibrosis | Neovascularization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (Days) | Control | PAE | Control | PAE | Control | PAE |

| 3 (Acute) | 0.93 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.08* |

| 28 (Chronic) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.09 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.2* | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2* |

Acute = primarily neutrophils, Chronic = macrophages and lymphocytes (minimal neutrophils).

P<0.05 compared to control at the same time point

Average severity = (severity of group/incidence), each animal represented 1 data point.

Fig. 3.

Representative photomicrographs of H&E and Verhoeff’s elastin stained venous cross sections on day 3 & 28. Increased neovascularization (arrows) was observed in control veins at 3 and 28-days. On day 28, intimal formation occurred predominately at the venous side of the anastomosis. I = Intima, M = Media, L = Lumen, ADV = Adventitia.

Matrix Metalloproteinase Localization

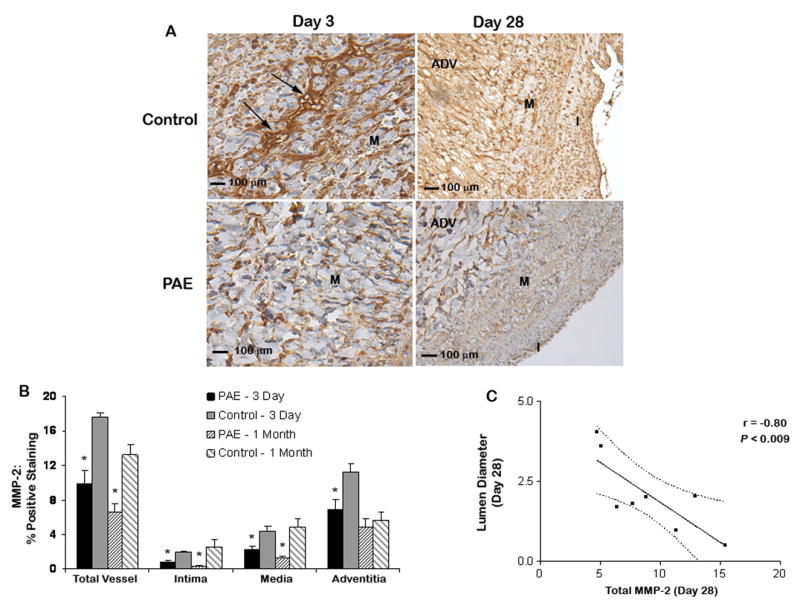

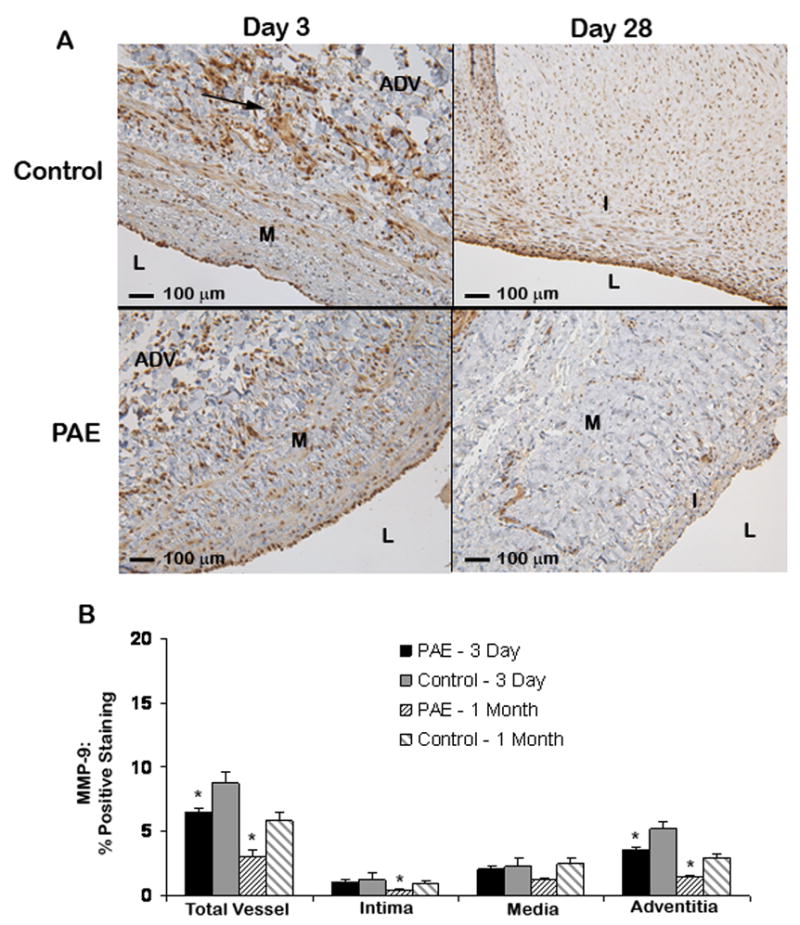

Immunohistochemical analysis of MMP expression in the total vessel, intima, media and adventitia 3 and 28-days after surgery revealed reduced expression in PAE treated veins compared to control veins with the majority of the positive staining localized to the extracellular matrix. In the control group, significant MMP-2 staining was observed in the adventitia, media and intima at day 3 (11.2 ± 1.0, 4.4 ± 0.6 and 2.1 ± 0.2 %, respectively) with the majority of staining located in the adventitia (Fig 4). Decreased expression of MMP-2 was observed in the adventitia, media and intima of PAE treated vessels at day 3 (6.9 ± 1.2, 2.3 ± 0.4 and 0.8 ± 0.2 %, respectively, P<.05). At 28-days, the amount of staining had decreased in the adventitia (5.7 ± 0.9 %) of control veins, while the staining in the media and intima were still significantly increased (4.9 ± 1.0 and 2.6 ± 0.8 %, respectively) compared to PAE treated veins (1.3 ± 0.2 and 0.3 ± 0.1, respectively, P <.05). MMP-9 staining was less intense in both the control and treated groups at both time points compared to MMP-2 staining (Appendix – Fig I). At 3-days there was reduced staining in the adventitia of PAE treated veins compared to control (P <.05). At 28-days, decreased MMP-9 expression was observed in the intima and adventitia of PAE treated veins compared to control (P< .05). A strong correlation was observed between total MMP-2 expression and lumen diameter at 28-days (r = −0.80, P < 0.009, Fig 4).

Fig 4.

MMP-2 localization in porcine jugular veins 3 and 28-days after surgery. (A) Media of a control vein with significant MMP-2 expression (arrows) compared to a PAE treated vein 3 days post-surgery. Increased MMP-2 expression was also observed at 1-month in control compared to PAE treated veins. I = Intima, M = Media, ADV = Adventitia. (B) Quantification of MMP-2 localization. A significant decrease in MMP-2 staining was observed in PAE treated veins compared to control at 3 days. Reduced MMP-2 staining was also observed at 1-month in the intima and media of veins treated with PAE compared to control. *P<.05 for PAE treated veins compared to control. (C) Pearson correlation (95% confidence interval). A strong correlation was observed between MMP-2 expression and lumen diameter of 28-day veins.

DISCUSSION

The major findings in the present study are that the adventitial application of endothelial implants significantly reduced MMP-2 expression within the venous wall at 3-days and increased venous lumen diameter and positive remodeling at 28-days in porcine AVG when compared to control. The data presented here provide further information on the mechanism of action of the perivascular implants and AVG failure. Positive remodeling is an important factor in the success or failure of an AVG, as the vein must accommodate arterial blood flow and pressure. Lumen diameter is the functional parameter used in vascular clinical trials and is determined not only by the degree of intimal thickening but is also influenced by the overall change in vessel size due to remodeling of the vessel wall. Therefore, in this study we examined the role of perivascular PAE on venous lumen size, remodeling and vein-graft stenosis. The mechanism of graft failure is a complex, multi-factorial pathologic process that involves a combination of many biologic events, it is therefore unlikely that a single agent aimed at any one process could prove successful in treating the cause of AVG failure. This is indeed the case, as despite success in animal models of AVG stenosis,15–18 approaches to reduce clinical graft failure have thus far proven unsuccessful.4 The endothelial cell implants described here represent a novel approach to addressing this problem. In addition to increasing venous lumen and vessel area and decreasing vascular stenosis, cell-containing implants also inhibited adventitial fibrosis at 28-days and neovascularization at 3 days and 28-days. In recent years, the adventitia has emerged as a key regulator of vascular remodeling.19 The adventitia consists primarily of fibroblasts, which proliferate and migrate toward the intima after vessel injury.8, 20 An increase in adventitial fibrosis may constrict the injured vessel and contribute to vascular remodeling and lumen loss.21

MMPs are necessary for the migration of adventitial and medial cells into the neointima after vascular injury by degrading extracellular matrix proteins.22 The upregulation of MMP-2 and -9 and down regulation of their inhibitors, TIMPs coincide with the formation of neointima and remodeling after vascular injury.23–25 Indeed, it has been shown that adventitial expression of MMP-2 increases after vascular injury in porcine AVG.26 In the present study, MMP-2 expression was reduced in PAE treated veins compared to control veins. The majority of MMP-2 activity was localized to the adventitia at day 3 and to the intima and media at 1-month. This is in agreement with previous studies suggesting that increased MMP activity may be necessary for cell migration to the intima to occur.18, 26 MMP-2 expression in the venous wall correlated strongly with lumen diameter at 28-days, suggesting that a potential mode of action of the perivascular endothelial implants in this model may be to modulate MMP-2 activity. MMP proteolysis is also a critical component of neovascularization,27 which has been implicated in the formation of stenosis and luminal narrowing.9, 28 MMP-2 in particular plays an essential role in extracellular matrix-induced angiogenesis.29 In the present study, adventitial neovascularization was reduced in veins treated with PAE containing implants compared to control veins. While adventitial inflammation has also been correlated with negative vascular remodeling7, minimal perivascular inflammation was noted in this study with no significant differences between groups. The absence of significant adventitial and luminal inflammation may have been due to the use of dexamethasone in this model.

Confluent endothelial cells release a variety of biological agents that in combination inhibit cell migration, proliferation and intimal thickening.30–32 The benefit of using perivascular implants over a single agent is the ability to theoretically target multiple biologic responses to injury, rather than a single event. HS secreted by endothelial cells is a potent inhibitor of SMC proliferation and migration as well as platelet activation, adhesion and thrombus formation.33, 34 TGF-β1 inhibits SMC and fibroblast proliferation and regulates the expression of MMPs.35, 36 While TIMP-2 can form a tight 1:1 inhibitory complex with MMP-2, TIMP-2 is also known to inhibit cell growth and angiogenesis.23, 27, 37 Endothelial derived NO is a potent vasodilator with many functions within the vessel wall and its response to injury.32, 38 NO has been shown to decrease MMP-2 and -9 activities and increased TIMP secretion.39 The lack of circumferential variation in the histopathologic analysis of venous tissue suggests that the effects of the implants and/or their factors are distributed circumferentially throughout the blood vessel wall. The effects rendered by the implants were determined to the due to the presence of cells as sham-seeded matrices produced no benefit. In previous porcine vascular injury models we have shown the presence of confluent endothelial cells within the implants 3-days post-implant.13 By 28-days, while cells can be found in the implant, there is substantial cell loss due in part to in vivo degradation of the gelatin matrix.11 However, the data presented here and supported by previous studies, indicates that the endothelial implants, or factors secreted by the cells, may provide control over the response to injury by influencing early events such as MMP expression and neovascularization.

A limitation of the present study was that zymography was not used and therefore the levels of active vs. latent MMP could not be assessed. Follow-up studies need to be performed to address this issue. The animals used in this study were young, healthy, not uremic and their grafts were not accessed during the time course of the study. Therefore, the impact of additional risk factors associated with hemodialysis patients were not assessed in this study. However, the data presented here suggest that adventitial endothelial cell implants may be useful in decreasing luminal narrowing in a clinical setting. Indeed, AV graft and fistula trials investigating endothelial implants in hemodialysis patients are currently ongoing.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Philip Seifert of Harvard-MIT and are grateful to Drs. Kathleen Funk and Jeffrey Wolf of Experimental Pathology Laboratories for their assistance in the pathological evaluation of tissue sections.

This study was supported by Pervasis Therapeutics and the following grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL49039 [E.R.E]; 5R21-HL080277-02, 5R21-HL076356-02, 1R01-HL083895-01 [J.H.L]).

Appendix – Fig. I

MMP-9 localization in porcine jugular veins 3 and 28 days after surgery. (A) Adventitia of a control vein shows increased MMP-9 staining (arrows) 3 days post-surgery compared to PAE treated veins at 3 days. Increased MMP-9 expression was also observed in the intima and adventitia at 1-month in veins treated with control Gelfoam compared to veins treated with PAE. I = Intima, M = Media, L = Lumen, ADV = Adventitia. (B) Quantification of MMP-9 localization. Reduced MMP-9 expression was observed in the adventitia of PAE treated veins compared to control at 3 days. A decrease in MMP-9 expression was also observed in the intima and adventitia of PAE treated veins compared to control at 1-month. *P <.05 for PAE treated veins compared to control.

Appendix - Table 1

Grading Criteria for Histomorphologic Findings

| Grade | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Fibroblasts | 0 | ≤ 20 fibroblasts per 40x HPF | 21–100 fibroblasts per 40x HPF | 101–200 fibroblasts per 40x HPF | > 200 fibroblasts per 40x HPF |

| Fibrosis/fibroplasias (adventitial) | Loose, normal collagen | Compacted continuous band < 100 microns or focal > 100 microns | Compacted continuous band < 200 microns or focal > 200 microns | Compacted continuous band < 300 microns or discontinuous or focally > 300 microns | Compacted continuous band < 300 microns |

| Neovascularization | 0 | Focal ≤ 5 vessels per 20x HPF | 5–15 vessels per 20x HPF | 16–25 vessels per HPF | > 25 vessels per HPF and/or Diffuse |

| Cellularity (by cell type, i.e. neutrophils, macrophages) | 0 | ≤ 20 cells per 40x HPF | 21–100 cells per 40x HPF | 101–200 cells per 40x HPF | > 200 cells per 40x HPF |

HPF = High Powered Field

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Woods JD, Turenne MN, Strawderman RL, Young EW, Hirth RA, Port FK, Held PJ. Vascular access survival among incident hemodialysis patients in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon BS, Novak L, Fangman J. Hemodialysis vascular access survival: upper-arm native arteriovenous fistula. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:92–101. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.29886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beathard GA. The treatment of vascular access graft dysfunction: a nephrologist’s view and experience. Advances in renal replacement therapy. 1994;1:131–147. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(12)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy-Chaudhury P, Kelly BS, Narayana A, Desai P, Melhem M, Munda R, Duncan H, Heffelfinger SC. Hemodialysis vascular access dysfunction from basic biology to clinical intervention. Advances in renal replacement therapy. 2002;9:74–84. doi: 10.1053/jarr.2002.33519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quinn SF, Schuman ES, Demlow TA, Standage BA, Ragsdale JW, Green GS, Sheley RC. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty versus endovascular stent placement in the treatment of venous stenoses in patients undergoing hemodialysis: intermediate results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:851–855. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mickley V, Gorich J, Rilinger N, Storck M, Abendroth D. Stenting of central venous stenoses in hemodialysis patients: long-term results. Kidney international. 1997;51:277–280. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gotoh R, Suzuki J, Kosuge H, Kakuta T, Sakamoto S, Yoshida M, Isobe M. E-selectin blockade decreases adventitial inflammation and attenuates intimal hyperplasia in rat carotid arteries after balloon injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2063–2068. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000145942.31404.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott NA, Cipolla GD, Ross CE, Dunn B, Martin FH, Simonet L, Wilcox JN. Identification of a potential role for the adventitia in vascular lesion formation after balloon overstretch injury of porcine coronary arteries. Circulation. 1996;1593:2178–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.12.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khurana R, Zhuang Z, Bhardwaj S, Murakami M, De Muinck E, Yla-Herttuala S, Ferrara N, Martin JF, Zachary I, Simons M. Angiogenesis-dependent and independent phases of intimal hyperplasia. Circulation. 2004;19110:2436–2443. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145138.25577.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleiner M, Kummer M, Mirlacher M, Sauter G, Cathomas G, Krapf R, Biedermann BC. Arterial neovascularization and inflammation in vulnerable patients: early and late signs of symptomatic atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;110:2843–2850. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146787.16297.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nugent HM, Rogers C, Edelman ER. Endothelial implants inhibit intimal hyperplasia after porcine angioplasty. Circ Res. 1999;84:384–391. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nugent HM, Edelman ER. Endothelial implants provide long-term control of vascular repair in a porcine model of arterial injury. J Surg Res. 2001;99:228–234. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nugent HM, Groothuis A, Seifert P, Guerraro JL, Nedelman M, Mohanakumar T, Edelman ER. Perivascular endothelial implants inhibit intimal hyperplasia in a model of arteriovenous fistulae: a safety and efficacy study in the pig. J Vasc Res. 2002;39:524–533. doi: 10.1159/000067207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baig K, Fields RC, Gaca J, Hanish S, Milton LG, Koch WJ, Lawson JH. A porcine model of intimal-medial hyperplasia in polytetrafluoroethylene arteriovenous grafts. The Journal of Vascular Access. 2003;4:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly BS, Narayana A, Heffelfinger SC, Denman D, Miller MA, Elson H, Armstrong J, Karle W, Nanayakkara N, Roy-Chaudhury P. External beam radiation attenuates venous neointimal hyperplasia in a pig model of arteriovenous polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft stenosis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2002;54:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fields RC, Baig K, Gaca J, Milton LG, Koch WJ, Lawson JH. Reduction of vascular intimal-medial hyperplasia in polytetrafluoroethylene arteriovenous grafts via expression of an inhibitor of G protein signaling. Annals of vascular surgery. 2005;19:712–718. doi: 10.1007/s10016-005-6805-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotmans JI, Pattynama PM, Verhagen HJ, Hino I, Velema E, Pasterkamp G, Stroes ES. Sirolimus-eluting stents to abolish intimal hyperplasia and improve flow in porcine arteriovenous grafts: a 4-week follow-up study. Circulation. 2005;111:1537–1542. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159332.18585.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotmans JI, Velema E, Verhagen HJM, Blankensteijn JD, de Kleijn DPV, Stroes ESG, Pasterkamp G. Matrix metalloproteinases inhibition reduces intimal hyperplasia in a porcine arteriovenous-graft model. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rey FE, Pagano PJ. The reactive adventitia: fibroblast oxidase in vascular function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000043452.30772.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G, Chen SJ, Oparil S, Chen YF, Thompson JA. Direct in vivo evidence demonstrating neointimal migration of adventitial fibroblasts after balloon injury of rat carotid arteries. Circulation. 2000;101:1362–1365. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zalewski A, Shi Y. Vascular myofibroblasts. Lessons from coronary repair and remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:417–422. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagase H, Woessner JF., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bode W, Fernandez-Catalan C, Grams F, Gomis-Ruth FX, Nagase H, Tschesche H, Maskos K. Insights into MMP-TIMP interactions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;878:73–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galis ZS, Khatri JJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling and atherogenesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Circulation research. 2002;90:251–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Southgate KM, Mehta D, Izzat MB, Newby AC, Angelini GD. Increased secretion of basement membrane-degrading metalloproteinases in pig saphenous vein into carotid artery interposition grafts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1640–1649. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.7.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misra S, Doherty MG, Woodrum D, Homburger J, Mandrekar JN, Elkouri S, Sabater EA, Bjarnason H, Fu AA, Glockner JF, Greene EL, Mukhopadhyay D. Adventitial remodeling with increased matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity in a porcine arteriovenous polytetrafluoroethylene grafts. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2890–2900. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas TL, Milkiewicz M, Davis SJ, Zhou AL, Egginton S, Brown MD, Madri JA, Hudlicka O. Matrix metalloproteinase activity is required for activity-induced angiogenesis in rat skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology. 2000;279:H1540–1547. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shigematsu K, Yasuhara H, Shigematsu H. Topical application of antiangiogenic agent AGM-1470 suppresses anastomotic intimal hyperplasia after ePTFE grafting in a rabbit model. Surgery. 2001;129:220–230. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.110769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas TL, Davis SJ, Madri JA. Three-dimensional type I collagen lattices induce coordinate expression of matrix metalloproteinases MT1-MMP and MMP-2 in microvascular endothelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:3604–3610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castellot JJ, Jr, Addonizio ML, Rosenberg R, Karnovsky MJ. Cultured endothelial cells produce a heparinlike inhibitor of smooth muscle cell growth. The Journal of cell biology. 1981;90:372–379. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.2.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furchgott RF, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. Faseb J. 1989;3:2007–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubanyi GM. The role of endothelium in cardiovascular homeostasis and diseases. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology. 1993;22 (Suppl 4):S1–14. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199322004-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kojima T, Leone CW, Marchildon GA, Marcum JA, Rosenberg RD. Isolation and characterization of heparan sulfate proteoglycans produced by cloned rat microvascular endothelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:4859–4869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forsten KE, Courant NA, Nugent MA. Endothelial proteoglycans inhibit bFGF binding and mitogenesis. Journal of cellular physiology. 1997;172:209–220. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199708)172:2<209::AID-JCP8>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinbergs ID, Brown L, Edelman ER. Cellular response to transforming growth factor-beta1 and basic fibroblast growth factor depends on release kinetics and extracellular matrix interactions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:29822–29829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borrelli V, di Marzo L, Sapienza P, Colasanti M, Moroni E, Cavallaro A. Role of platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor beta1 the in the regulation of metalloproteinase expressions. Surgery. 2006;140:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoegy SE, Oh HR, Corcoran ML, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP-2) suppresses TKR-growth factor signaling independent of metalloproteinase inhibition. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:3203–3214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott-Burden T, Vanhoutte PM. Regulation of smooth muscle cell growth by endothelium-derived factors. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 1994;21:91–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gurjar MV, Sharma RV, Bhalla RC. eNOS gene transfer inhibits smooth muscle cell migration and MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2871–2877. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.12.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]