Abstract

Purpose

In the present study, the authors developed novel models to stimulate blood vessel formation (hemangiogenesis) versus lymphatic vessel formation (lymphangiogenesis) in the cornea.

Methods

Micropellets loaded with high-dose (80 ng) or low-dose (12.5 ng) basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were placed in BALB/c corneas. Angiogenic responses were analyzed by immunohistochemistry to quantify blood neovessels (BVs) and lymphatic neovessels (LVs) to 3 weeks after implantation. Areas covered by BV and LV were calculated and expressed as a percentage of the total corneal area (percentage BV and percentage LV). Hemangiogenesis (HA) and lymphangiogenesis (LA) were also assessed after antibody blockade of VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3

Results

Although high-dose bFGF stimulation induced a more potent angiogenic response, the relative LV (RLV = percentage LV/percentage BV × 100) was nearly identical with high- and low-doses of bFGF. Delayed LA responses induced 3 weeks after implantation of high-dose bFGF resulted in a lymphatic vessel-dominant phenotype. Interestingly, the blockade of VEGFR-2 significantly suppressed BV and LV. However, the blockade of VEGFR-3 inhibited only LV (P = 0.0002) without concurrent inhibition of BV (P = 0.79), thereby resulting in a blood vessel-dominant phenotype

Conclusions

An HA-dominant corneal phenotype can be obtained in BALB/c mice 2 weeks after implantation of an 80-ng bFGF micropellet with VEGFR-3 blockade. Alternatively, an LA-dominant corneal phenotype can be obtained 3 weeks after implantation of an 80-ng bFGF micropellet without supplementary modulating agents. These models will be useful in evaluating the differential contribution of BV and LV to a variety of corneal abnormalities, including transplant rejection, wound healing and microbial keratitis.

Stratification of clinical risk factors for corneal graft rejection has identified recipient bed vascularity as the principal cause of earlier and more fulminant rejection episodes1–3 because blood vasculature is the conduit by which immune cells gain entry to the corneal matrix.4 However, lymphatic neovessels in the cornea may be as, or even more, important because these vessels provide alloantigen-bearing antigen-presenting cells effective access to regional lymph nodes. However, because the presence of lymphatic vessels is undetectable by clinical slit lamp examination, unlike blood neovessels, the importance of lymphangiogenesis in graft rejection may be underappreciated. Previous reports have demonstrated that suppression of the eye-lymphatic axis abrogates the induction of alloimmunity and potently augments graft survival.5,6 However, precise delineation of the differential regulation of hemangiogenesis (HA) and lymphangiogenesis (LA), the manner by which these distinct processes regulate transplant immunity, and a large number of diverse corneal inflammatory conditions have not been addressed.

To this end, the study of HA and LA individually is particularly difficult because pathologic conditions stimulate angiogenic and inflammatory responses concurrently, leading to coincident HA and LA. With the use of corneal suture placement to induce inflammation-associated neovascularization, however, Bock et al.7 were able to selectively inhibit corneal lymphangiogenesis through systemic blockade of VEGFR3, and Dietrich et al.8 achieved a similar effect through the systemic blockade of α5 integrin. Alternatively, intrastromal micropellet implantation with low-dose FGF has been shown to selectively stimulate lymphangiogenesis and has been further shown to be amplified through the administration of exogenous soluble VEGFR-1.9,10 Thus, though FGF was initially characterized as the sole inducer of HA, its role in inducing LA has also been appreciated.11–13

In the present study, we developed two distinct angiogenic models, an HA-dominant phenotype, characterized by the presence of blood neovessels (BVs) and a relative absence of lymph neovessels (LVs) and an LA-dominant phenotype, characterized by the presence of LV with a paucity of BV. We used the micropocket assay to this end because it is considered a specific method to induce corneal neovascularization. Furthermore, micropellets were impregnated with high-dose (80 ng) basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). As described herein, this dose is important in stimulating a robust angiogenic response. This is relevant to the considerable interest that has recently emerged in further understanding the strong angiogenic responses associated with microbial keratitis in addition to high-risk corneal transplantation.14–18 Consequently, the development of in vivo models that can robustly, yet differentially, induce HA compared with LA dominance would be considerably useful in studying the disparate roles of blood and lymphatic vessels in a number of corneal immune-mediated and inflammatory abnormalities.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were used in all experiments. Animals were anesthetized intraperitoneally (120 mg/kg ketamine and 20mg/kg xylazine per body weight) before any surgery and were treated in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Experiments described herein were conducted under institutional animal care and use committee approval.

Pellet Implantation

High-dose (80 ng) and low-dose (12.5 ng) bFGF (a gift from BRB Preclinical Repository, National Cancer Institute) pellets were prepared as previously described.18 An initial half-thickness linear incision was made at the center of cornea with a disposable 30° microknife (FST; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A lamellar pocket incision was then made parallel to the corneal plane with a von Graefe knife (FST; Applied Biosystems) and advanced to the temporal limbus at a lateral canthal area. The pellets were positioned into the pocket 1 mm apart from the limbal vascular arcade, and tetracycline ophthalmic ointment was applied to the eye after pellet implantation.

Slit Lamp Biomicroscopic Examination

Eyes were examined by slit lamp biomicroscopy on postoperative days 7 and 14. Photographs were taken through retroillumination, whereby pupils were first dilated (2.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride and 1% tropicamide ophthalmic solution) before slit lamp photomicrographs were taken.

Immunohistochemistry and Morphometry of HA and LA

After taking photographs under the slit lamp, five mice per group were killed 1, 2, and 3 weeks after implantation, and freshly enucleated eyes were prepared into corneal flat mounts. Immunohistochemical staining was performed with FITC-conjugated CD31/PECAM-1 (rat-anti-mouse antibody; 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Staining against LYVE-1 (lymphatic endothelium-specific hyaluronic acid receptor; goat-anti-rabbit antibody; 1:400; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was also performed with purified antibody followed by rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. To quantify the level of BV formation (CD31high/LYVE-1−) or LV formation (CD31low/LYVE-1high), low-magnification (2×) micrographs were captured, and the area covered by BVs and LVs was calculated (NIH ImageJ software 1.34; developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html) and expressed as a percentage of the total corneal area (%BV and %LV). In addition, to specify the level of LA in relation to total angiogenic response, the relative LV (RLV) was calculated using this equation: RLV = %LV/%BV × 100.

Real-Time PCR

The suture model was used by placement of intrastromal sutures (11–0) with three interrupted figure-of-eight knots on the circumference of the paracentral cornea for 1 versus 3 weeks, or normal cornea as a control. RNA was subsequently isolated from recipient corneas (RNeasy Micro Kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse transcribed (Superscript III Kit; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time PCR was performed (TaqMan Universal PCR MasterMix; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and primers were preformulated for VEGF-A (assay ID Mm00437304_ml), VEGF-C (assay ID Mm00437313_ml), VEGF-D (assay ID Mm00438965_ml), VEGFR-3 (assay ID Mm00433337_ml) and GAPDH (assay ID Mm99999915_gl) (Applied Biosystems). Results were derived from the comparative threshold cycle method and normalized by GAPDH as an internal control. Values obtained from normal corneas were then used to calculate relative mRNA expression for experimental corneas.

VEGF Receptor Neutralization with Blocking Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies were used to block VEGFR-2 (DC101) or murine VEGFR-3 (mF4–31C1).19–23 Both blocking antibodies were supplied by Bronislaw Pytowski (Imclone Systems Inc., New York, NY) based on our signed material transfer agreement. One milligram (0.5 mL) of anti–mouse VEGFR-2 or anti–mouse VEGFR-3, or both, was injected through the intraperitoneal route at days 0 (before pellet implantation), 2, 4, 7, 10, and 13 to neutralize the function of each receptor. The same amount of rat immunoglobulin (IgG) was injected as an isotype control in control mice. Mice were grouped based on the treatment received (n = 5 per group).

Statistical Analysis

The values of BV, LV, and RLV were statistically compared between different growth factor dosages (12.5 and 80 ng) and time points (weeks 1, 2, and 3) with the use of ANOVA. The inhibitory effects of specific VEGFR-2 or -3 blockades on HA and LA were evaluated by comparing percentage BV or percentage LV of each treatment group with those of the nontreated control group with the two-tailed Student's t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Biomicroscopic Comparison of Low- versus High-Dose bFGF Stimulation on Corneal Hemangiogenesis

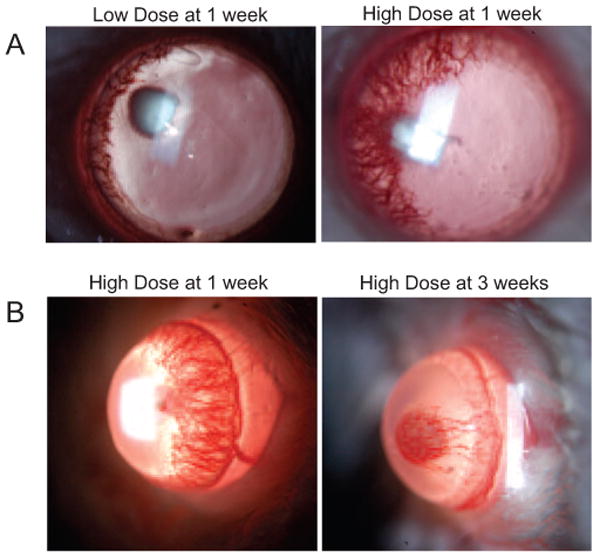

Because disparate doses of bFGF stimulation may induce different levels of blood vessel ingrowth, we first examined this potential effect on BALB/c corneas through biomicroscopic slit lamp examination. Either low-dose (12.5 ng) or high-dose (80 ng) bFGF-containing micropellets were implanted into the corneal stroma and examined as late as 3 weeks after implantation to evaluate the inducibility and sustainability of the stimulated hemangiogenesis. We found the response to be substantially stronger with high-dose bFGF, as measured by slit lamp examination (Fig. 1A), which was particularly obvious at 1 week after implantation. This time point also coincided with peak hemangiogenesis after high-dose bFGF stimulation because subsequent time points showed substantial regression of neovessels (Fig. 1B). This regression was also indicated by a change in the angiogenic pattern: week 1 revealed a robust ringlike pattern of BVs, whereas weeks 2 and 3 resembled a more localized and restricted wedge-shape pattern (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Biomicroscopic examination of corneal hemangiogenesis induced by low- versus high-dose bFGF stimulation. (A) Stimulation of robust hemangiogenesis requires implantation of a high-dose (80 ng) bFGF-impregnated micropellet. BALB/c mice (n = 5) were implanted with either a low-dose (12.5 ng) or a high-dose micropellet into the corneal stroma and compared 1 week after implantation by slit lamp examination. (B) Stimulation with high-dose bFGF peaked at week 1 after implantation. BALB/c mice (n = 5) were implanted with a high-dose (80 ng) micropellet and followed up until 3 weeks after implantation.

Development of an LA-Dominant Corneal Phenotype

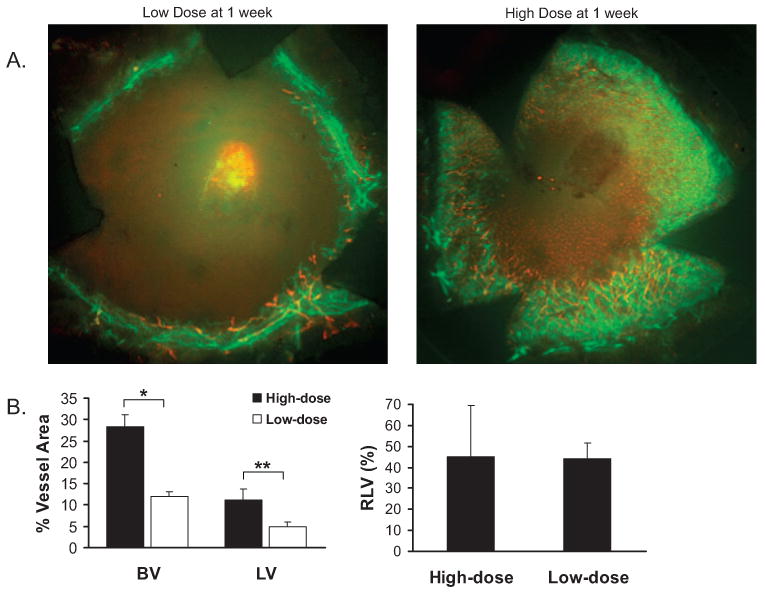

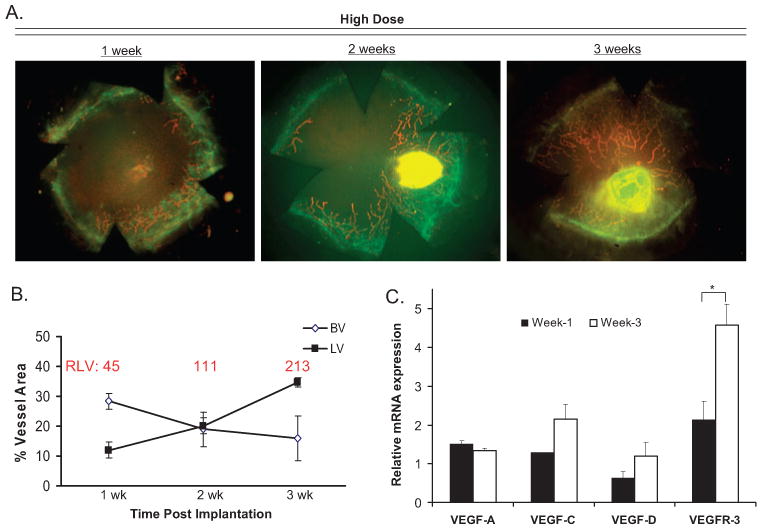

Corneas implanted with low- or high-dose bFGF pellets were prepared into flat mounts and evaluated until 3 weeks after implantation through immunofluorescence microscopy. LVs were identified as CD31low/LYVE-1high, and BVs were identified as CD31high/LYVE-1− vessels (Fig. 2A). The percentage LV, percentage BV, and RLV were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Interestingly, though the RLV values obtained were relatively identical between the two doses, both the percentage LV and the percentage BV observed after low-dose bFGF stimulation were significantly lower (P = 0.0007 and 0.0014, respectively) than those observed with high-dose bFGF mice (Fig. 2B). In addition, further evaluation of high-dose bFGF mice indicated that maximal percentage LV was observed 3 weeks after implantation, whereas concurrent percentage BV was relatively marginal (Figs. 3A, 3B). Therefore, these data indicate that an LA-dominant corneal phenotype can be obtained in BALB/c mice 3 weeks after implantation of an 80-ng bFGF micropellet.

Figure 2.

Analysis of corneal hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis induced by low- versus high-dose bFGF stimulation. (A) Representative micrographs demonstrate the importance of high-dose bFGF stimulation in eliciting a hemangiogenic and lymphangiogenic response. Corneal flat mounts of BALB/c mice stimulated with low- or high-dose bFGF were prepared 1 week after implantation and immunostained against CD31 (green) and LYVE-1 (red). (B) Percentage area of host cornea covered by BV (CD31high/LYVE-1−, green) or LV (CD31low/LYVE-1high, red) was calculated (n = 5 per group). Relative lymphatic vessel values (RLV, %), which equal LV/BV × 100, were also calculated. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis (*P = 0.0007; **P = 0.0014).

Figure 3.

Development of an LA-dominant corneal phenotype. (A) Representative micrographs demonstrate the LA-dominant phenotype observed 3 weeks after high-dose bFGF stimulation. (B) Corneal flat mounts immunostained against CD31 (green) and LYVE-1 (red) were quantified for percentage LV, percentage BV, and RLV (red) as late as 3 weeks after implantation (n = 5 per time point). (C) Corneas, collected at 1 rather than 3 weeks after stimulation (n ≥ 3 corneas per group), were assayed through real-time PCR to quantify mRNA levels of HA- or LA-associated genes, including VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and VEGFR-3. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results, and the Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis (*P = 0.04).

To verify these observations indicating that the LA responses can increase while concomitant HA responses subside over time, we compared mRNA levels of various genes whose expressions are important in eliciting HA or LA (Fig. 3C). Recipient corneas were therefore collected at 1 versus 3 weeks after stimulation of neovascularization, and real time-PCR was used to quantify mRNA levels of VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and VEGFR-3. We found that whereas levels of VEGF-A subsided modestly, a near twofold increase (or greater) was observed in the levels of VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and VEGFR-3 (P = 0.04) at week 3 compared with week 1.

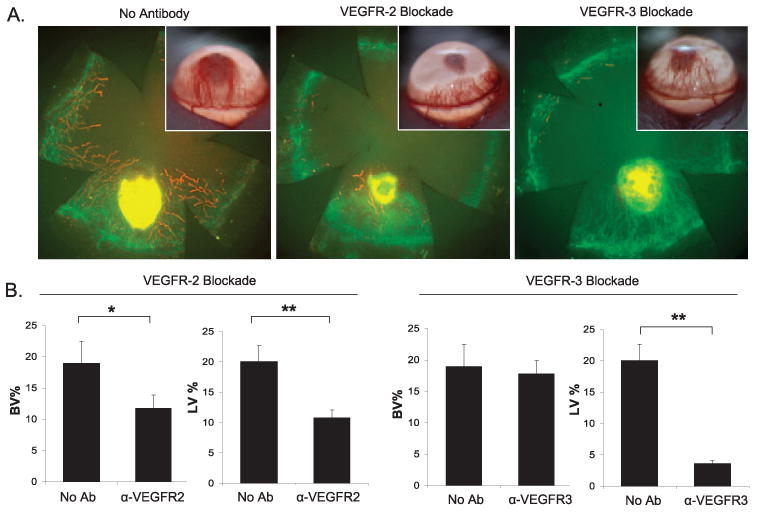

Development of an HA-Dominant Corneal Phenotype

To develop an HA-dominant corneal phenotype, we focused on high-dose bFGF stimulation because low-dose stimulation induced a far less robust angiogenic response. To further facilitate the development of an HA-dominant phenotype, we also tested whether specific VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3 antibody blockade could minimize the RLV and thereby promote an HA-dominant phenotype (Fig. 4). Although their mechanisms of stimulating HA are different, the ligation of either VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3 may be important in eliciting the HA response.9,11 Thus, BALB/c mice were implanted with 80-ng bFGF micropellets and treated systemically with anti-VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3. Control mice were obtained by implanting an 80-ng bFGF micropellet without VEGFR antibody blockade. VEGFR-2 blockade inhibited percentage BV and percentage LV substantially compared with nontreated controls (Fig. 4B). However, VEGFR-3 blockade only led to a significant inhibition of LV relative to the nontreated controls (P = 0.0002), whereas concurrent percentage BV was statistically similar (P = 0.79) to the percentage of nontreated controls (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Development of an HA-dominant recipient model. (A) Systemic VEGFR-3 blockade leads to an HA-dominant phenotype. Representative images of biomicroscopic and immunohistochemical micrographs demonstrate the effect of VEGFR-2 versus VEGFR-3 blockade (or no treatment) at 2 weeks after high-dose bFGF stimulation. Corneal flat mounts were immunostained against CD31 (green) and LYVE-1 (red). (B) Percentage area of cornea covered by BV (CD31high/LYVE-1−, green) or LV (CD31low/LYVE-1high, red) was calculated (n = 5 per group). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine statistical significance (**P < 0.01; *P < 0.05).

In the aggregate, these data indicate that an HA-dominant corneal phenotype can be obtained in BALB/c mice 2 weeks after implantation of an 80-ng bFGF micropellet and VEGFR-3 blockade. Alternatively, an LA-dominant corneal phenotype can be obtained in BALB/c mice 3 weeks after implantation of an 80-ng bFGF micropellet, without supplementary modulating agents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of LA- and HA-Dominant Corneal Models

| LA-Dominant Model | HA-Dominant Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse strain | BALB/c | BALB/c |

| Pellet description | bFGF, 80 ng | bFGF, 80 ng |

| Time | 3 weeks after implantation | 2 weeks after implantation |

| Modulating agent | N/A | αVEGFR-3 |

| Phenotype characterization | Slit lamp examination showed marginal hemangiogenesis | Slit lamp examination showing robust hemangiogenesis |

| Immunohistochemistry indicated CD31low LYVE-1high neovessels | Immunohistochemistry indicating CD31high LYVE-1− neovessels |

N/A, not applicable.

Discussion

In this study, we have developed novel angiogenic models for investigation of the role of BVs versus LVs in corneal immunity. The first model is a hemangiogenic-dominant model whereby blood neovessels are present with minimal presence of lymphatic neovessels. In contrast, the lymphangiogenic-dominant model is characterized by robust lymphatic neovessels whereas the presence of blood neovessels is marginal. Chang et al.9 demonstrated that bFGF can selectively induce lymphatic vessels using a 12.5-ng bFGF micropellet implanted into the corneal stroma. However, in the present study, we observed that angiogenic stimulation with a 12.5-ng bFGF micropellet relative to 80 ng stimulation was too weak to be considered high risk from an immunoinflammatory standpoint and not reflective of the significant angiogenic responses seen in clinical settings.

It has been shown that hemangiogenic vessels are initiated earlier and can persist longer than lymphangiogenic vessels, implicating that preexisting blood vascular bed may be necessary to guide lymphangiogenesis.19,20 Recent studies, including our current work, have indicated that this is not always the case. Lymphangiogenesis, for example, can be initiated before or even in the absence of hemangiogenesis.9 Here we also demonstrate, using high-dose bFGF (80 ng) micropellets, an LA-dominant phenotype in the cornea, which is attributed to the persistence, or even increase, in lymphangiogenesis in spite of a regression in hemangiogenesis. We found that the mean RLV value was 213 at week 3 compared with 45 at week 1 after implantation (approximately 4.7-fold difference), and percentage LV was nearly twofold higher than percentage BV at 3 weeks after transplantation. Moreover, this was corroborated by quantitative (real-time) PCR measuring mRNA levels of relevant VEGF species. Increases in VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and VEGFR-3 (but not VEGF-A) were observed at 3 weeks rather than 1 week after stimulation.

We did not anticipate this delayed nature in the LA response to bFGF, which became apparent only by 2 and 3 weeks after implantation. However, this observation may be explained because bFGF cannot directly ligate VEGFR-3 to stimulate LA. Hence, activation of the VEGFR-3 receptor would rely on downstream activation, possibly by de novo secretion of VEGF-C or VEGF-D from inflammatory cells.9,11 Indeed, macrophages are rich sources of prolymphatic factors.21 Thus our data most likely highlight the importance of LA stimulation through an indirect means.

The development of an HA-dominant phenotype required the addition of modulating factors after bFGF stimulation (unlike in the previous LA-dominant phenotype), and we tested whether this could be achieved through systemic blockade of VEGFR-2 or VEGFR-3. We did this because though bFGF can directly stimulate HA, it can also lead to inflammation-associated activation of VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3.16,24,25 Indeed, we observed that VEGFR-2 blockade inhibited HA and LA levels similarly after bFGF stimulation because the reductions of percentage BV and percentage LV compared with nontreated controls were nearly identical and thereby not suitable in the creation of an HA-dominant phenotype. In contrast, VEGFR-3 blockade selectively inhibited LA while HA remained intact and uninhibited because the reduction of percentage LV compared with nontreated controls was nearly 10-fold, indicating a suitable method for creating an HA-dominant phenotype.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that an HA-dominant corneal phenotype can be obtained in BALB/c mice 2 weeks after implantation with an 80-ng bFGF micropellet and VEGFR-3 blockade. Alternatively, an LA-dominant corneal phenotype can be obtained in BALB/c mice 3 weeks after implantation of an 80-ng bFGF micropellet, without supplementary modulating agents. Future investigations using these models will help discern the respective and differential roles of these two angiogenic compartments in high-risk corneal transplantation and other immune corneal disorders.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NEI-RO1–12963 (RD) and by the New England Transplant Research Fund (RD).

Footnotes

Disclosure: E.-S. Chung, None; D.R. Saban, None; S.K. Chauhan, None; R. Dana, None

References

- 1.Coster DJ. Mechanisms of corneal graft failure: the erosion of corneal privilege. Eye. 1989;2:251–262. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maguire MG, Stark WJ, Gottsch JD, et al. Risk factors for corneal graft failure and rejection in the collaborative corneal transplantation studies: Collaborative Corneal Transplantation Studies Research Group. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1536–1547. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams KA, Roder D, Esterman A, Muehlberg SM, Coster DJ. Factors predictive of corneal graft survival: report from the Australian Corneal Graft Registry. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu S, Dana MR. Expression of cell adhesion molecules on limbal and neovascular endothelium in corneal inflammatory neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1427–1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamagami S, Dana MR. The clinical role of draining lymph nodes in corneal alloimmunization and graft rejection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1293–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, Hamrah P, Cursiefen C, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 mediates induction of corneal alloimmunity. Nat Med. 2004;10:813–815. doi: 10.1038/nm1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bock F, Onderka J, Dietrich T, Bachmann B, Pytowski B, Cursiefen C. Blockade of VEGFR3-signalling specifically inhibits lymphangiogenesis in inflammatory corneal neovascularisation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:115–119. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich T, Onderka J, Bock F, et al. Inhibition of inflammatory lymphangiogenesis by integrin alpha5 blockade. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:361–372. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang LK, Garcia-Cardena G, Farnebo F, et al. Dose-dependent response of FGF-2 for lymphangiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11658–11663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404272101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang L, Kaipainen A, Folkman J. Lymphangiogenesis new mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;979:111–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubo H, Cao R, Brakenhielm E, Makinen T, Cao Y, Alitalo K. Blockade of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 signaling inhibits fibroblast growth factor-2-induced lymphangiogenesis in mouse cornea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8868–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062040199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rusnati M, Presta M. Fibroblast growth factors/fibroblast growth factor receptors as targets for the development of anti-angiogenesis strategies. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:2025–2044. doi: 10.2174/138161207781039689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cenni E, Perut F, Granchi D, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis via FGF-2 blockage in primitive and bone metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert PY, Liekfeld A, Metzner S, et al. Specific antibody production in herpes keratitis: intraocular inflammation and corneal neovascularization as predicting factors. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:210–215. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huq S, Liu Y, Benichou G, Dana MR. Relevance of the direct pathway of sensitization in corneal transplantation is dictated by the graft bed microenvironment. J Immunol. 2004;173:4464–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cursiefen C, Cao J, Chen L, et al. Inhibition of hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis after normal-risk corneal transplantation by neutralizing VEGF promotes graft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2666–2673. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Illigens BM, Yamada A, Fedoseyeva EV, et al. The relative contribution of direct and indirect antigen recognition pathways to the alloresponse and graft rejection depends upon the nature of the transplant. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:912–925. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenyon BM, Voest EE, Chen CC, Flynn E, Folkman J, D'Amato RJ. A model of angiogenesis in the mouse cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1625–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cursiefen C, Maruyama K, Jackson DG, Streilein JW, Kruse FE. Time course of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis after brief corneal inflammation. Cornea. 2006;25:443–447. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000183485.85636.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paavonen K, Puolakkainen P, Jussila L, Jahkola T, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 in lymphangiogenesis in wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1499–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maruyama K, Ii M, Cursiefen C, et al. Inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis in the cornea arises from CD11b-positive macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2363–2372. doi: 10.1172/JCI23874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruns C, Shrader M, Harrison M, et al. Effect of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 antibody DC101 plus gemcitabine on growth, metastasis and angiogenesis of human pancreatic cancer growing orthotopically in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:101–108. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pauli SA, Tang H, Wang J, et al. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF receptor 2 pathway is critical for blood vessel survival in corpora lutea of pregnancy in the rodent. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1301–1311. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tille JC, Wood J, Mandriota SJ, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-2 antagonists inhibit VEGF- and basic fibroblast growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:1073–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pepper MS, Mandriota SJ, Jeltsch M, Kumar V, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C synergizes with basic fibroblast growth factor and VEGF in the induction of angiogenesis in vitro and alters endothelial cell extracellular proteolytic activity. J Cell Physiol. 1998;177:439–452. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199812)177:3<439::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]