Abstract

Background

Assessing self-management knowledge can guide physicians in teaching patients necessary skills.

Objective

To develop and test the Asthma Self-Management Questionnaire (ASMQ).

Methods

The ASMQ was developed from patient interviews. Validity was evaluated by comparison with the established Knowledge, Attitude, and Self-Efficacy Asthma Questionnaire, and test-retest reliability was evaluated with repeated administration (mean, 5 days apart) in 25 patients (mean age, 41 years; 96% women). The ASMQ was further described in additional patients by comparison with cross-sectional self-management practices and longitudinal change in Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire scores.

Results

The 16-item, multiple-choice ASMQ measures knowledge of preventive strategies, inhaler use, and medications and generates a score of 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more correct responses. The ASMQ was correlated with the Knowledge, Attitude, and Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (r = 0.58) and had a Cronbach α of 0.71. The correlation between administrations was 0.78, and the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.58. When given to another 231 patients (mean age, 41 years; 74% women), the mean (SD) ASMQ score was 60 (20). Patients with better ASMQ scores were more likely to own peak flow meters (P = .04) and to have received flu vaccines (P = .03). For 12 months, these patients received self-management information through workbooks and telephone reinforcement. Patients with higher ASMQ scores after 12 months were more likely to have clinically important improvements in quality of life compared with patients with lower ASMQ scores (65% vs 46%; P = .01).

Conclusions

The ASMQ is valid and reliable and is associated with clinical markers of effective self-management and better asthma outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Educating patients about asthma is an essential component of comprehensive care.1 Ideally, this education should provide a foundation of knowledge and should focus on topics that are pertinent to each patient.2 In addition to physicians, patients also derive knowledge from other sources, such as anecdotal experiences of others and the media. Given that accuracy of information from these sources may vary, physicians should evaluate patients’ knowledge of asthma to address gaps in information, to reinforce correct practices, and to uncover misconceptions.

Several questionnaires have been developed to measure patients’ general knowledge of asthma. For the most part, these questionnaires address a broad spectrum of topics, such as epidemiology, physiology, triggers, and treatments.3–6 These questionnaires are practical means to evaluate what patients understand about asthma, its complexity, and goals of therapy. They have been used with patients in ambulatory care and emergency department settings, as well as during asthma educational programs.4,5,7–12 General knowledge about asthma, however, is not the same as knowledge about self-management. Thus, a questionnaire specifically focusing on knowledge of self-management would be useful in assessing understanding of behaviors necessary to control asthma. The objectives of this study were to develop an asthma self-management questionnaire based on input from patients, to test its validity and reliability, and to demonstrate its performance in cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses with adult asthma patients followed up in a primary care practice.

METHODS

The development and testing of the Asthma Self-Management Questionnaire (ASMQ) were conducted in 3 phases. Patients for each phase were enrolled at the Cornell Internal Medicine Associates primary care practice in New York City. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Rights in Research at the Weill Cornell Medical College/New York Presbyterian Hospital. All patients provided written informed consent.

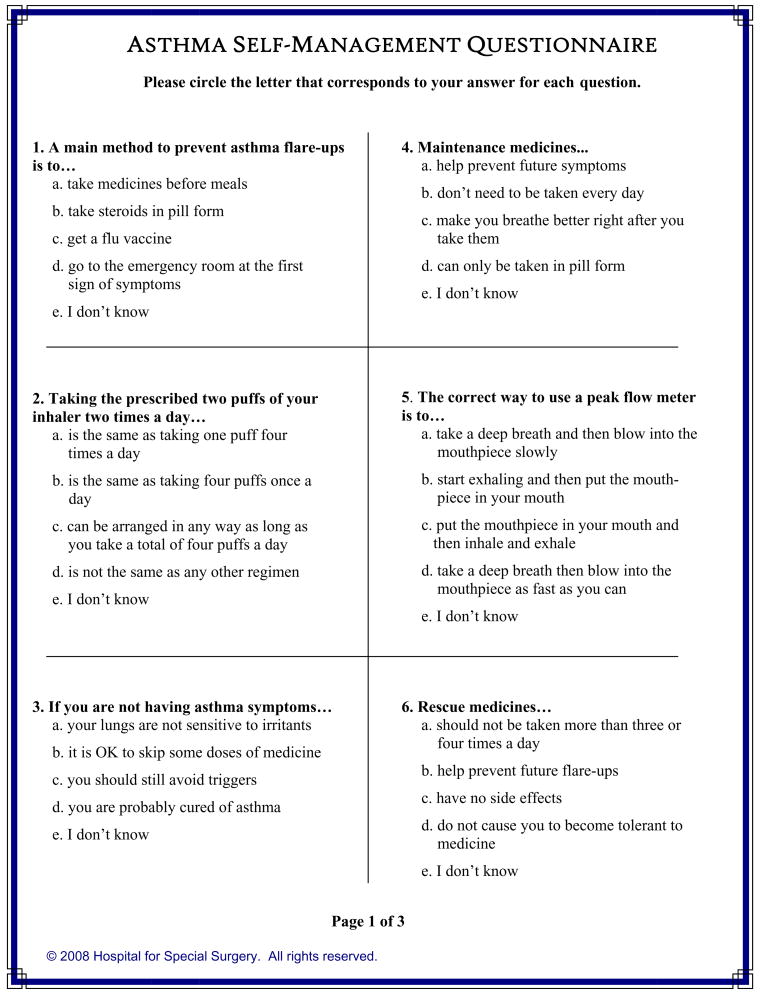

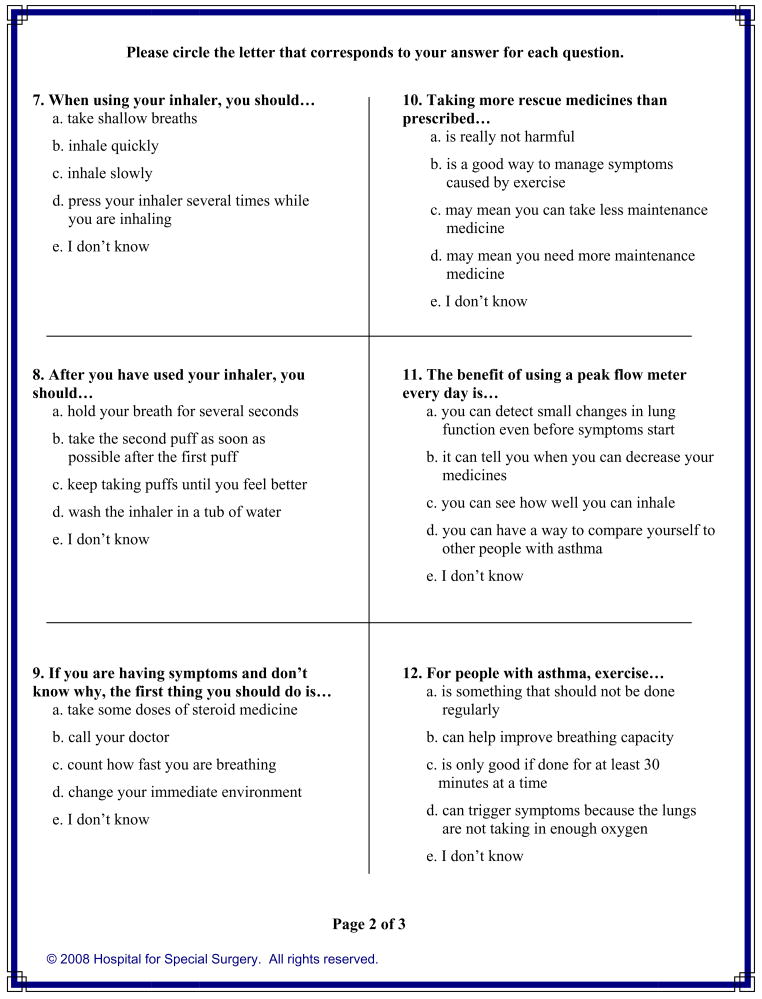

Phase 1: Assembly of Questions

Questions were assembled based on information from patients who were participating in a trial to improve asthma-related quality of life (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Patients were eligible for the trial if they had mild to moderate persistent asthma, were English speaking, and had no major comorbidity. As part of the trial, patients were asked open-ended questions about how asthma affected daily life and how they managed asthma. From their responses, challenges and misconceptions about self-management were gleaned, and 16 questions with multiple-choice response options were composed. Preferred (ie, correct) responses were formulated based on current expert opinion reported in the literature. Incorrect responses were formulated from misconceptions and inaccurate practices described by patients. The questions and responses then were presented to a convenience sample of 10 patients from the same trial who provided comments and suggested modifications.

Figure 1.

Asthma Self-Management Questionnaire. Reproduced with permission from Hospital for Special Surgery; © copyright 2008 Hospital for Special Surgery. All Rights reserved.

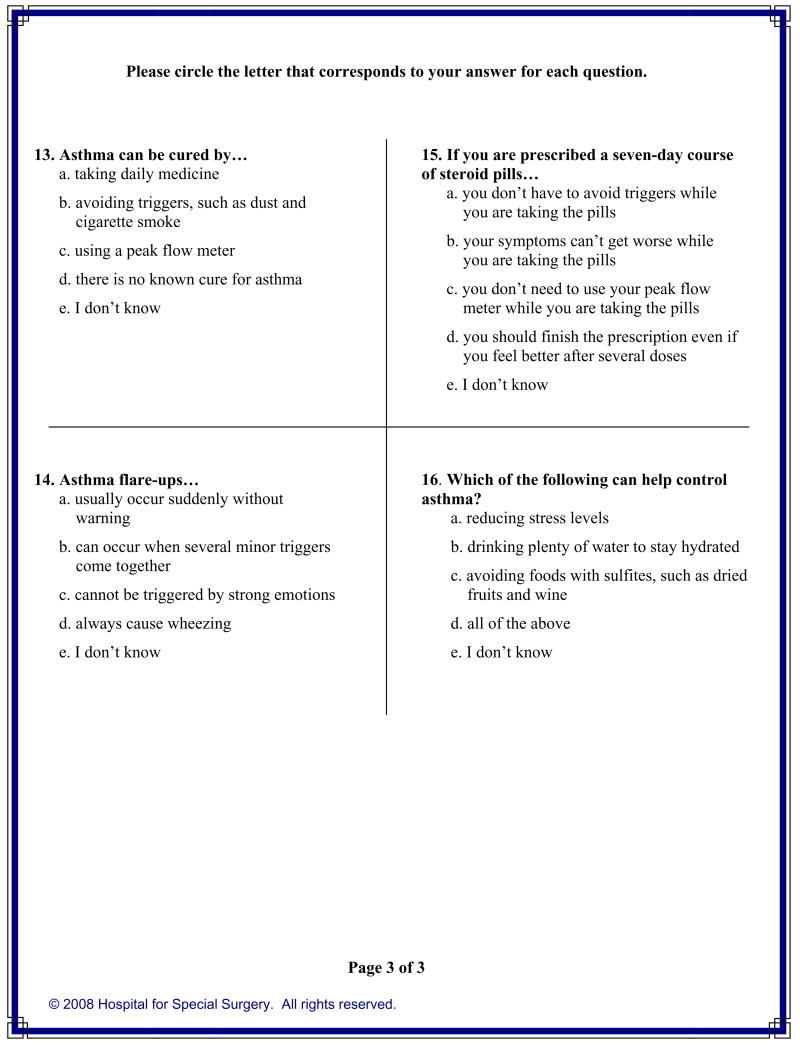

Figure 2.

Asthma Self-Management Questionnaire scoring. Reproduced with permission from Hospital for Special Surgery; © copyright 2008 Hospital for Special Surgery. All Rights reserved.

Phase 2: Validity and Reliability Testing

An additional convenience sample of 25 patients from the same trial participated in phase 2. Validity was evaluated by comparing the ASMQ with the knowledge subscale of the Knowledge, Attitude, and Self-Efficacy Asthma Questionnaire (KASE-AQ).3 The KASE-AQ has been shown to be valid, reliable, and responsive. The knowledge subscale is composed of 20 multiple-choice questions that measure awareness of basic asthma physiology, use of medications, avoidance of triggers, and management of exacerbations. Raw scores can range from 0 to 20. For our study, the raw score was multiplied by 5 to range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more knowledge. To evaluate validity, the ASMQ and the knowledge subscale of the KASE-AQ were administered by trained interviewers during a single in-person interview at the time of a routine office visit. To evaluate reliability, the same patients completed the ASMQ a second time several days later during a telephone interview.

Phase 3: Demonstration

The properties of the ASMQ were demonstrated in another sample of patients enrolled in a 12-month trial to increase walking and exercise in asthma patients.13,14 Patients were eligible for this trial if they had mild to moderate persistent asthma, were English speaking, were willing to increase physical activity, and had no major medical or mobility-limiting comorbidity. Patients were enrolled during routine office visits and completed a series of clinical and psychosocial measurements, including the ASMQ. To minimize possible asthma exacerbations during the trial, patients were given an informational workbook about asthma.15 The workbook addressed asthma triggers and medications and suggested self-management techniques. Patients were reminded to review the workbook during bimonthly follow-ups. Of the 258 patients enrolled in the trial, 231 had time to complete the ASMQ at enrollment and again at 12 months. At both time points patients also completed the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ), a well-established 32-item questionnaire that assess symptoms, limitations, and emotional and environmental aspects of asthma.16 An overall AQLQ score can range from 1 to 7, and higher scores reflect better status. A change in score of 0.5 or more reflects a clinically important improvement.17 Information about self-management practices also were obtained at enrollment, specifically whether the patient owned and used a peak flow meter and whether the patient received a flu vaccine.

For phase 2, internal validity of the ASMQ was evaluated with the Cronbach α correlation. External validity between the ASMQ and the knowledge subscale of the KASE-AQ was evaluated with the Pearson correlation. Reliability between the first and second administration of the ASMQ was evaluated by measuring concordance with the intraclass correlation coefficient. The association between the first and second administration of the ASMQ also was measured with the Pearson correlation. For phase 3, the cross-sectional performance of the ASMQ was demonstrated by comparing ASMQ scores with self-management practices and asthma-related quality of life (AQLQ scores) using t tests. Within-patient changes in enrollment to 12-month ASMQ and AQLQ scores were compared with paired t tests. The longitudinal performance of the ASMQ was evaluated by comparing enrollment and 12-month ASMQ scores with the percentage of patients who did and did not have a clinically important improvement in AQLQ scores, defined as an increase of 0.5 or more, using χ2 tests. Analyses were performed with SAS statistical software.18

RESULTS

Phase 1

On the basis of feedback from the convenience sample of 10 patients, modifications to the questionnaire were made, specifically restructuring terms for maintenance and rescue medications, reordering response options, and adding the response option of “I don’t know” to each of the 16 questions. The final questionnaire has a Flesch-Kincaid19 reading level of grade 6.8 and addresses knowledge of preventive strategies, proper use of inhalers, differences between maintenance and rescue medications, and use of peak flow meters. One point is assigned to each correct response, and the raw score equals the sum of all points. The final transformed score was determined by the equation (raw score/16) × 100 and ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more knowledge of self-management.

Phase 2

The 25 patients who participated in the validity and reliability testing had a mean age of 41 years and 96% were women (Table 1). The mean (SD) ASMQ score from the first administration was 65 (18) (range, 19–88), corresponding to 10 correct responses of a possible 16. The mean (SD) ASMQ score from the second administration, which occurred a mean of 5 (range, 2–9) days later, was 66 (15) (range, 38–88). The mean (SD) KASE-AQ knowledge score was 49 (15) (range, 25–80). The Pearson correlations between the KASE-AQ and the first and second administrations of the ASMQ were 0.58 and 0.64, respectively. The Pearson correlation between the first and second administration of the ASMQ was 0.78, and the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.58.

Table 1.

Patient and Asthma Characteristics at Enrollment for Testing and Demonstration Samplesa

| Characteristics | Testing sample (n = 25) | Demonstration sample (n = 231) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 41 (13) | 41 (11) |

| Women | 24 (96) | 170 (74) |

| Race | ||

| White | 13 (52) | 131 (57) |

| African American | 10 (40) | 44 (19) |

| Other | 2 (8) | 56 (24) |

| Latino | 10 (40) | 70 (30) |

| College graduate | 9 (36) | 148 (64) |

| Asthma duration, mean (SD), y | 25 (11) | 22 (14) |

| FEV1,b mean (SD), % | 86 (20) | 91 (18) |

| Medicationsc | ||

| None | 0 (0) | 14 (6) |

| β-Agonists only | 3 (12) | 96 (42) |

| Maintenance medications | 22 (88) | 121 (52) |

| Owns a peak flow meter | 16 (64) | 78 (34) |

| Received flu vaccine | Not recorded | 66 (29) |

| Ever hospitalized for asthma | 13 (52) | 73 (32) |

| Ever treated in the emergency department for asthma | 23 (92) | 139 (60) |

| AQLQ score, mean (SD) | 3.9 (1.4) | 5.0 (1.3) |

| ASMQ score, mean (SD) | 65 (18) | 60 (20) |

Abbreviations: AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; ASMQ, Asthma Self-Management Questionnaire; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

FEV1 was measured at enrollment with a portable spirometer.

Medications reported to be currently taking.

Phase 3

The 231 patients who participated in the demonstration phase had a mean age of 41 years, and 74% were women (Table 1). The mean (SD) enrollment ASMQ score was 60 (20) (range, 0–100; median, 62.5). No differences were found in score based on age (P = .60) or sex (P = .81). Only 1 patient (0.4%) had a score of 0 (floor score), and 3 patients (1.3%) had a score of 100 (ceiling score). With respect to self-management practices, only 34% owned a peak flow meter and 29% received a flu vaccine for the most recent winter season. The mean (SD) quality-of-life (AQLQ) score was 5.0 (1.3) (range, 1.6–7.0). The ASMQ scores were higher for patients who owned a peak flow meter, received a flu vaccine, and had better quality-of-life scores (Table 2).

Table 2.

ASMQ Scores Compared With Self-management Practices and Quality-of-Life Scores for the 231 Patients in the Demonstration Sample

| Cross-sectional sample at enrollment |

||

|---|---|---|

| ASMQ score, mean (SD) | P value | |

| Owns peak flow meter | 64 (19) | .04 |

| Does not own peak flow meter | 58 (21) | |

| Received flu vaccine | 65 (21) | .04 |

| Did not receive flu vaccine | 59 (21) | |

| AQLQ score better than group mean | 64 (20) | .003 |

| AQLQ score worse than group mean | 56 (20) | |

Abbreviations: ASMQ, Asthma Self-Management Questionnaire; AQLQ, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire.

The mean (SD) ASMQ score at 12 months was 68 (18) (range, 13–100; median, 68.8) (Table 2). The mean (SD) within-patient change between enrollment and 12-month ASMQ scores was 8 (15) (P < .001). The mean (SD) 12-month AQLQ score was 5.9 (1.0) (range, 2.5–7.0), the mean (SD) within-patient AQLQ change after 12 months was 0.9 (1.1) (P < .001), and 59% had an increase in score of 0.5 or more, corresponding to a clinically important improvement. Patients with higher ASMQ scores after 12 months were more likely to have a clinically important improvement in AQLQ scores compared with patients with lower ASMQ scores (65% vs 46%; P = .01).

DISCUSSION

The 16-item ASMQ is valid and reliable and corresponds to change in clinical asthma status over time. The questionnaire addresses knowledge of preventive strategies, proper use of inhalers, differences between rescue and maintenance medications, and use of peak flow meters. A major strength of the questionnaire is that it was not developed a priori by physicians but instead was derived during an iterative process based on feedback from patients. As such, the questions address real day-to-day situations and decisions faced by patients, and the incorrect response options reflect misconceptions that patients have about managing asthma. Thus, the final patient-derived questionnaire captures self-management issues from the patient’s point of view.

An important goal in developing the questionnaire was to balance ease of administration with comprehensiveness. To increase comprehensiveness, we used a multiple-choice response format, which permitted us to expand the breadth of the material covered per question. This is beneficial because reasons why certain responses are incorrect can be discussed when the questionnaire is reviewed with patients. In addition, offering the response option of “I don’t know” decreases the chances of guessing the correct answers and also communicates to patients that not knowing correct answers is anticipated and acceptable. When presenting the questionnaire to patients, we encouraged them to choose this option, where applicable, to identify what topics we needed to focus on during subsequent discussions.

To maximize ease of administration, we composed short phrases for questions and responses. The questionnaire has a Flesch-Kincaid reading level of grade 6.8 and requires approximately 5 minutes to complete when self-administered. When administered during an interview, approximately 8 to 10 minutes should be allocated to repeat questions and responses if necessary. We found the questionnaire to be well received by patients when administered both ways. In addition, we found that questions about rescue and maintenance medications were better understood if names of familiar medications were given as examples. Therefore, we recommend the patient’s medications be cited in these questions, or representative examples of medications be cited if the questionnaire is given to a group of patients, such as in a research trial.

Although recruited from the same practice, patients in the testing and demonstration samples differed somewhat clinically. These differences were due to variations in eligibility criteria for the parent trials from which these patients were drawn. For example, patients in the demonstration sample were enrolled in a trial to increase walking and exercise and thus tended to have milder symptoms, to not require maintenance medications, and to have better asthma-related quality-of-life scores. Including patients with different disease severity in the various phases, however, permitted us to evaluate the ASMQ in patients with a range of clinical conditions.

We tested our questionnaire against the 20-item knowledge subscale of the KASE-AQ, a reliable general questionnaire that measures various aspects of asthma knowledge.3 The KASE-AQ was developed to account for patient-centered factors that may contribute to difficulties in managing asthma. The factors measured by the KASE-AQ were found to be associated with certain outcomes, such as medication compliance and the use of emergency asthma care.12 Other scales, such as the 31-item Asthma General Knowledge Questionnaire for Adults, were developed to evaluate effectiveness of asthma educational programs and showed improvement in areas specifically addressed by the programs.4,5 The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute assembled a survey of 9 questions entitled “Check Your Asthma IQ,” which offers a simple way to increase patients’ awareness of issues related to asthma.20 This brief quiz showed poor understanding of asthma among patients who presented to the emergency department for exacerbations.8,11 Also, several general knowledge questionnaires have been developed specifically for pediatric asthma patients and their caregivers.6,21

With the exception of the KASE-AQ, which has multiple-choice responses, most of these other questionnaires have true or false responses with a third option to cover uncertainty.5,6,20 Although simpler to complete, these questionnaires are less likely to depict the process patients use in making treatment decisions. At the other end of the spectrum, several studies evaluated self-management knowledge by presenting patients with narratives of asthma exacerbations and asking them open-ended questions about what actions they would take at various stages.22,23 Points were assigned for actions that were appropriate at each stage. Although this technique approximates clinical reality, it is time consuming and difficult to administer to large groups of patients.

This study has several limitations. First, it was developed in an urban primary care practice and may not reflect self-management issues of patients in other settings. Second, there is no standard method to measure test-retest reliability for an informational questionnaire because the learning effect from the first administration may affect responses to the second administration. Therefore, we reported both the Pearson and intraclass correlation coefficients. Third, to establish validity it would have been ideal to compare the ASMQ with observed or documented self-management behaviors. In addition, the utility of the ASMQ in clinical practice would be confirmed by measuring changes in behavior resulting from completing the questionnaire and discussing it with physicians. Fourth, we did not formally test responsiveness during a longer period or time in the demonstration sample because we did not administer the self-management intervention according to a set protocol. However, all patients in the demonstration sample received information about self-management through a workbook and periodic reinforcements by telephone. Therefore, our finding that asthma quality-of-life and ASMQ scores changed in parallel provides preliminary evidence that the ASMQ corresponds to clinical status over time.

The ASMQ is a valid and reliable questionnaire that is associated with effective self-management behaviors and outcomes. It addresses multiple aspects of self-management and can be used in clinical and research settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and physicians at the Cornell Internal Medicine Associates for their participation.

Funding Sources: This study was supported by grants NHLBI K23 04067 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00197964) and NHLBI N01 HC 25196 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00195117) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose.

Previous presentation: Presented in poster form at the 2008 International Meeting of the American Thoracic Society; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; May 20, 2008.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00197964 and NCT00195117.

References

- 1.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma – Summary Report 2007. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2008. NIH publication 08–5846. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Challenges in asthma patient education. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1225–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wigal JK, Stout C, Brandon M, et al. The Knowledge, Attitude, and Self-Efficacy Asthma Questionnaire. Chest. 1993;104:1144–1148. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.4.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson SR, Scamagas P, German DF, et al. A controlled trial of two forms of self-management education for adults with asthma. Am J Med. 1993;94:564–576. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen RM, Jones MP. The validity and reliability of an asthma knowledge questionnaire used in the evaluation of a group asthma education self-management program for adults with asthma. J Asthma. 1998;35:537–545. doi: 10.3109/02770909809048956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho J, Bender BG, Gavin LA, O’Connor SL, Wamboldt MZ, Wamboldt FS. Relations among asthma knowledge, treatment adherence, and outcome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:498–502. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams MV, Baker DW, Honig EG, Lee TM, Nowlan A. Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest. 1998;114:1008–1015. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radeos MS, Leak LV, Lugo BP, Hanrahan JP, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Risk factors for lack of asthma self-management knowledge among ED patients not on inhaled steroids. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:253–259. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.21712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sin MK, Kang DH, Weaver M. Relationships of asthma knowledge, self-management, and social support in African American adolescents with asthma. Inter J Nurs Studies. 2005;42:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdulwadud OA, Abramson MJ, Forbes AB, Walters EH. The relationships between patients’ related variables in asthma: implications for asthma management. Respirology. 2001;6:105–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer IH, Sternfels P, Fagan JK, Copeland L, Ford JG. Characteristics and correlates of asthma knowledge among emergency department users in Harlem. J Asthma. 2001;38:531–539. doi: 10.1081/jas-100107117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scherer YK, Bruce S. Knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy and compliance with medical regimen, number of emergency department visits, and hospitalizations in adults with asthma. Heart Lung. 2001;30:250–257. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.116013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Boutin-Foster C, Mancuso CA, et al. Randomized controlled trials of positive affect and self-affirmation to facilitate healthy behaviors in patients with cardiopulmonary diseases: rationale, trial design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancuso CA, Choi TN, Westermann H, Briggs WM, Wenderoth S, Charlson ME. Measuring physical activity in asthma patients: two-minute walk test, repeated chair rise test, and self-reported energy expenditure. J Asthma. 2007;44:333–340. doi: 10.1080/02770900701344413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mancuso CA, Sayles W, Robbins L, Allegrante JP. Novel use of patient-derived vignettes to foster self-efficacy in an asthma self-management workbook. Health Promot Pract. doi: 10.1177/1524839907309865. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschke R, Hiller TK. Evaluation of impairment of health-related quality of life in asthma: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax. 1992;47:76–83. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:81–87. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS User’s Guide: Statistics Version 5 ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Jr, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel. Millington, TN: Naval Technical Training, US Naval Air Station, Memphis; 1975. Research Branch Report 8–75. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;88:468–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wade S, Weil C, Holden G, et al. Psychosocial characteristics of inner-city children with asthma: a description of the NCICAS psychosocial protocol: National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997;24:263–276. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199710)24:4<263::aid-ppul5>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolbe J, Vamos M, James F, Elkind G, Garrett J. Assessment of practical knowledge of self-management of acute asthma. Chest. 1996;109:86–90. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Palen J, Klein JJ, Seydel ER. Are high generalised and asthma-specific self-efficacy predictive of adequate self-management behaviour among adult asthma patients? Patient Educ Counsel. 1997;32:S35–S41. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]