Abstract

Purpose

To assess the prevalence and the dosimetric and clinical predictors of mandibular osteoradionecrosis (ORN) in patients with head and neck (HN) cancer who underwent pre-therapy dental evaluation and prophylactic treatment according to a uniform policy and were treated with intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT).

Methods and Materials

Between 1996–2005 all patients with HN cancer treated with parotid gland sparing IMRT in prospective studies underwent dental examination and prophylactic treatment according to a uniform policy including extractions of high-risk, periodontally involved and non-restorable teeth in parts of the mandible expected to receive high doses, fluoride supplements, and guards aiming to reduce electron backscatter off metal teeth restorations. The IMRT plans included dose constraints for the maximal mandibular doses and reduced mean parotid gland and non-involved oral cavity doses. Retrospective analysis of grade ≥2 (clinical) ORN was performed.

Results

176 patients had minimal follow-up 6 months. Thirty-one (17%) had teeth extractions prior to radiation and 13 (7%) post-radiation. 75% and 50% of the patients received at least 65Gy and 70Gy to ≥ 1% of the mandibular volumes, respectively. Fall-off across the mandible characterized the dose distributions: the average gradient (in the axial plane containing the maximal mandibular dose) was 11 Gy (range 1–27Gy, median 8Gy). At median 34 months follow-up there were no cases of ORN (95% CI, 0; 2%).

Conclusions

The use of a strict prophylactic dental care policy and IMRT resulted in no case of clinical ORN. In addition to the dosimetric advantages offered by IMRT, meticulous dental prophylactic care is likely an essential factor in reducing ORN risk.

Keywords: IMRT, intensity modulated radiation therapy, osteoradionecrosis, head and neck cancer

Introduction

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) of the mandibular bone is a well documented complication of radiation therapy (RT) for head and neck cancer 1–4. Generally, bones are resistant to high doses of radiation and will not present any overt damage as long as the overlying soft tissue remains intact and the bone is not subjected to excessive stress or trauma. Mendenhal has recently noted that the presentation of ORN after RT varies from small, asymptomatic bone exposures that may remain stable for months or years or heal with conservative management, to severe necrosis necessitating surgical intervention and reconstruction (3). Several risk factors are associated with the development of ORN, including age, sex, general health, primary tumor site and stage, proximity of the tumor to bone or its invasion, dentition status, type of treatment (external beam RT, brachytherapy, surgery, chemotherapy or the combination), RT dose, associated trauma as teeth extraction prior to and after radiation or surgery 1–3.

Since 1996, patients with HN cancer have been treated at the University of Michigan with IMRT techniques which primarily aimed to reduce major salivary gland doses, and in addition they produced dose gradients across the mandible. During that time period, all patients underwent pre-radiation dental evaluation and prophylactic care according to uniform policies. The original aim of this retrospective study was to compare mandibular doses and clinical factors in patients receiving IMRT who did or did not develop ORN. As no ORN was found in any of these patients, we present the mandibular dose distributions and relevant clinical factors, especially those related to dental care, which may have contributed to the lack of this complication.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients evaluated in this retrospective study received IMRT to the bilateral neck with curative intent, participated in prospective clinical protocols, did not receive previous radiation, and had at least 6 months follow-up after the completion of RT. Following Institutional Review Board approval their charts and treatment plans were reviewed.

Dental evaluation and treatment

Prior to radiation all patients underwent dental evaluation at the Hospital Dentistry clinic. During this consult, complete medical, dental, social and family history were obtained, and potential oral side effects of radiation therapy, including xerostomia, dental caries, ORN, mucositis, and trismus were reviewed with the patient and strategies for prevention were discussed. The examination includes a tooth-by-tooth evaluation, with particular attention to teeth in parts of the jaws expected to receive a high dose (> 50 Gy). The periodontal condition was evaluated, and teeth with mobility, significant pocketing, furcation involvement or advanced recession would be recommended for extraction. All patients underwent panoramic radiographs which was supplemented in some patients by intraoral periapical radiographs if necessary to evaluate for periapical abscesses, caries, and the periodontal condition. Teeth with non-restorable caries, or caries that extended to the gum line, teeth with large, compromised restorations with significant periodontal attachment loss (pocketing >5 mm), and those with severe erosion or abrasion were extracted if they were in parts of the jaws expected to receive a high dose (the posterior mandible and maxilla ipsilateral to the tumor, and the posterior mandible contralateral to the tumor). Teeth residing in the anterior mandible were not considered for extraction unless the primary tumor was in the oral cavity. Decisions about extraction were significantly affected by the patient’s competence and interest in performing meticulous oral hygiene, and by the past history of dental service usage. A more aggressive approach was made following surgical oral reconstructions which inhibit oral hygiene or in patients with trismus, due to their negative impact on the prognosis for the teeth. Extractions were performed as soon as possible after examination and it was attempted to achieve primary closure when possible in the extraction sites. The residual alveolar ridges were prepared for dentures by performing any needed pre-prosthetic surgery such as alveoloplasty and torus removal. The start of RT was delayed by at least 14 days after extraction to allow for complete healing of the extraction site.

Patient education

Oral hygiene, including secular brushing and flossing, was reviewed with each patient. Daily use of high concentrated fluoride gel (1.1% neutral sodium fluoride) either in a fluoride carrier or by brush-on technique was also recommend and a prescription was given to the patient. Written information and instructions were provided, including oral care during and after radiation therapy, using the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research4 and in-house supplement material.

Additional dental procedures

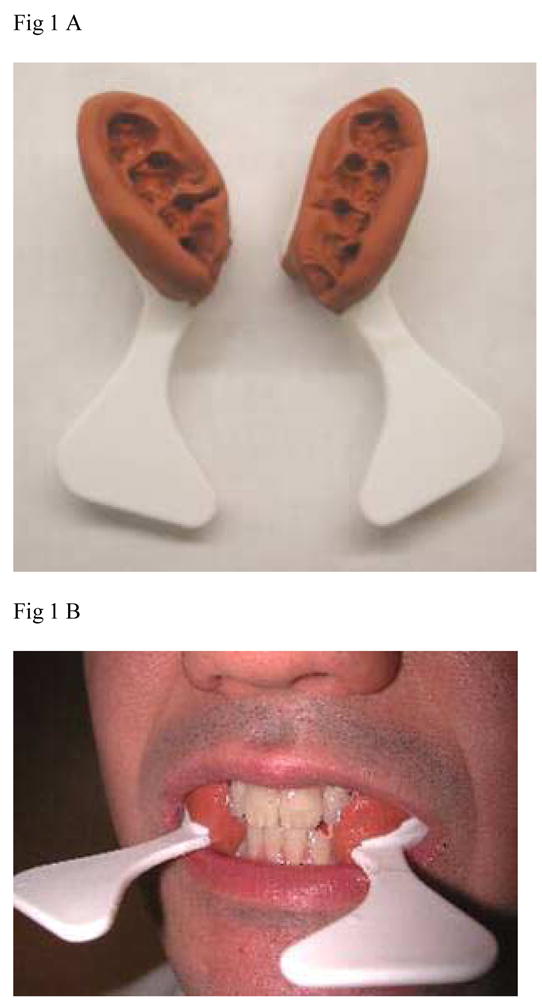

For all patients with dentitions heavily restored with metallic restorations, radiation guards were used (Fig. 1). These were made from polyvinyl siloxane putty (Reprosil, Caulk-Dentsply, York, PA) and were intended to provide a five millimeter separation between the metallic restorations and the soft tissue, with the intention of reducing electron backscatter off the metal onto the soft tissue. The base and catalyst of the putty were hand-mixed and placed on posterior quadrant triple-trays (Sullivan Schein, Melville, NY) and placed in the mouth. Four wooden tongue blades were placed between the upper and lower incisors and the patient was asked to close until the tongue blades were snug between the anterior teeth. After setting time of about five minutes, the guards were removed and disinfected. They were trimmed to achieve a five millimeter thickness. The silicone was polished using a satin wheel (E.C. Moore, Dearborn, MI) and delivered to the patient along with instructions in use and care. The guards were in place during the simulation to ensure that they were taken in account in the treatment planning dosimetry.

Figure 1.

Stents devised to reduce electron backscatter off dental metal restorations to the adjacent soft tissue. A. After completion, B. In place. If clinically required, teeth separation and tongue depression can be achieved by inserting a tongue depressor during the preparation of the stents or by making separate stents for the mandible and maxilla.

Radiotherapy

Target definition and radiation techniques have been detailed elsewhere 5–9. The Planning Target Volumes (PTVs) were created by uniform expansion of the Clinical Target Volumes (CTVs) by 0.5 cm. In recent years, on-line imaging and daily correction of the systematic set-up errors by the radiation therapists were found to reduce the systematic errors to mean ± SD 1 ± 1.5 mm (unpublished data) and the PTV expansion has been reduced to 3 mm. Patients were treated until 2002 using static multisegmental IMRT7–8 and afterwards by inverse-planned beamlet IMRT9. The prescribed target doses were 70 Gy to the gross tumor PTVs in 35 fractions and low and high-risk CTVs were prescribed 56–64 Gy, respectively, at 1.6–1.8 Gy fractions.

The optimization cost functions penalized the maximal mandibular dose (<72 Gy), mean parotid gland (≤26 Gy), and mean non-involved oral cavity dose (≤ 30 Gy). The oral cavity structure included the mandible, buccal mucosa, tongue, base of tongue, floor of mouth and palate, and its delineation has previously been detailed10. The noninvolved oral cavity was obtained by subtracting the PTVs from the oral cavity volume. In all patients the plans strived to address target prescription goals while reducing target dose inhomogeneity. In recent years the planning goals included also reduced doses to the swallowing structures.11,12

For the purposes of this study, all available treatment plans were reviewed (148 plans, 84%). The mandibular dose distributions were recalculated and their dose volume histograms (DVHs) were re-generated for all patients, using the edge/octree model calculation and the convolution/superposition model for patients treated with multisegmental IMRT and beamlet IMRT, respectively.

Follow-up

All patients were followed every 6–8 weeks during the first 2 post-therapy years and every 3–4 months afterwards in both Radiation Oncology and Head and neck Surgery clinics. Follow-up at the Hospital Dentistry/Oral Surgery clinic was made when specific dental problems or suspected ORN were observed in the other clinics.

Definition of ORN

Several staging/grading systems were suggested for ORN 2,13,14, taking into consideration the response to hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) 14, presence of pathologic fracture 13 and clinical presentation 2 or a combination of the above 15. We have elected to use the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE)15 for the grading of ORN in this series and planned to retrospectively assign a grade according to clinical and radiographic findings detailed in the patients’ charts. ORN definition and grading according to CTCAE v3.0 includes Grade 1: Asymptomatic, radiographic findings only; Grade 2: Symptomatic and interfering with function, minimal bone removal indicated; Grade 3: Symptomatic and interfering with daily life activities, operative intervention or hyperbaric oxygen indicated; Grade 4: Disabling. As routine radiographs were not performed after therapy in the majority of patients, we aimed at identifying patients who had Grade ≥2 ORN, defining Grade 2 as bony exposure observed for at least two follow-up clinic visits (persisting at least 6–8 weeks). The follow-up notes from all clinics were reviewed for each patient to capture all possible cases of ORN.

Results

Between March 1996 and March 2005, 188 patients were treated with IMRT in prospective trials. Nine patients who had less then 6 months follow-up (5 lost to follow-up earlier than 6 months, 2 died of pneumonia or trauma and 2 died with lung metastases), and three patients who did not complete the radiation course, were excluded from this analysis (none had ORN at last contact), and the total number of patients evaluated in this study was 176. Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The large majority had oral or oropharyngeal primary tumors. All 20 patients with laryngeal or hypopharyngeal cancers presented with advanced neck lymphadenopathy and the posterior mandible was within or close to the lymphatic nodal targets. One hundred and seven patients (61%) received primary RT and 69 (39%) received postoperative RT. 108 patients were treated with concurrent chemotherapy: cisplatin-based in 22 patients, carboplatinum-based in 44, and 43 patients received a combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 55 (29–86) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 172 |

| African American | 2 |

| Asian | 2 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 128 |

| Female | 48 |

| Tumor Site | |

| Oral cavity | 32 |

| Oropharynx | 120 |

| Larynx | 7 |

| Hypopharynx | 13 |

| Other | 4 |

| Tumor Stage (AJCC) | |

| I | 2 |

| II | 7 |

| III | 40 |

| IVA | 114 |

| IVB | 12 |

| Recurrent disease | 1 |

Pre-therapy Dental examination and treatment information were available for 174 patients (99%). Sixteen patients (9%) were edentulous at presentation and six patients (3%) had all their remaining teeth extracted prior to radiation.157 patients (89%) were dentulous during radiation. Thirty patients (19%) had pre-therapy mandibular teeth extractions, median of 2 (range 1–8) teeth. In almost all cases the extractions were from the posterior parts of the mandible which were expected to receive high RT doses. All other patients (122 patients, 69%) were cleared to start radiation therapy without extraction. Thirteen patients had post- radiation mandibular teeth extractions at the University of Michigan Dental Clinic. Six of these patients had teeth extracted from parts of the mandible which had received maximal dose > 60 Gy, two of whom received HBO prior to the procedure. Seven other patients had teeth extracted from parts of the mandible which had received lower maximal doses. The median follow-up after extractions in these patients is 26 months. Some patients elected to proceed with post-therapy dental follow-up with their local dentist, therefore information regarding post-radiation extractions was not available for all patients.

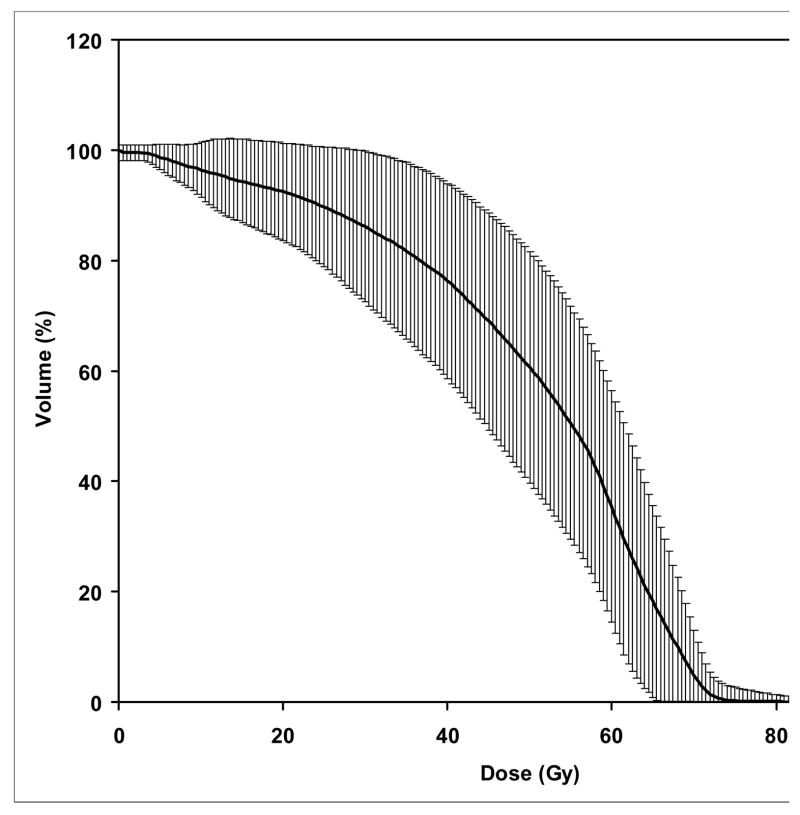

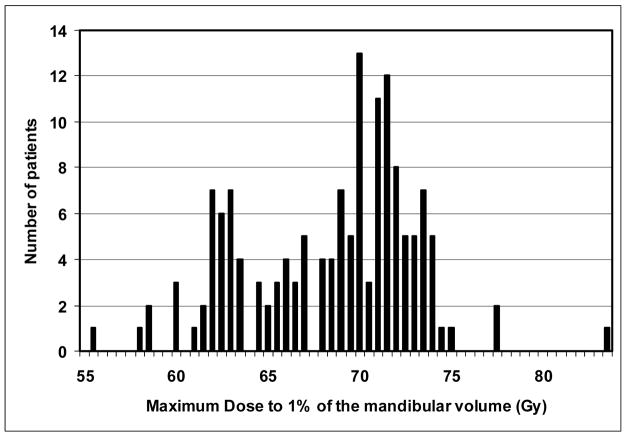

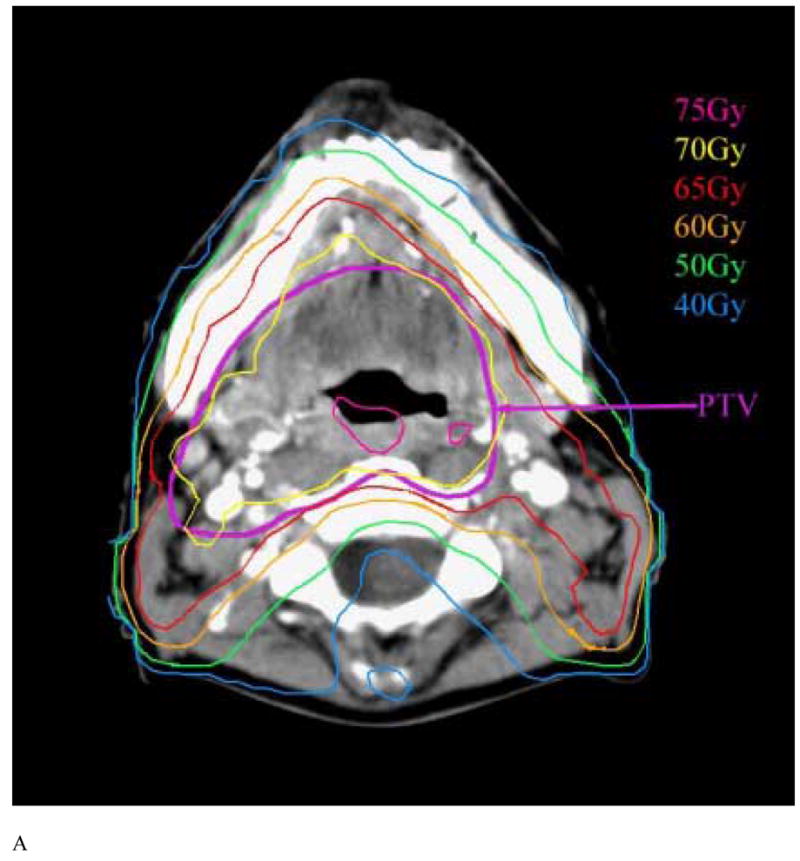

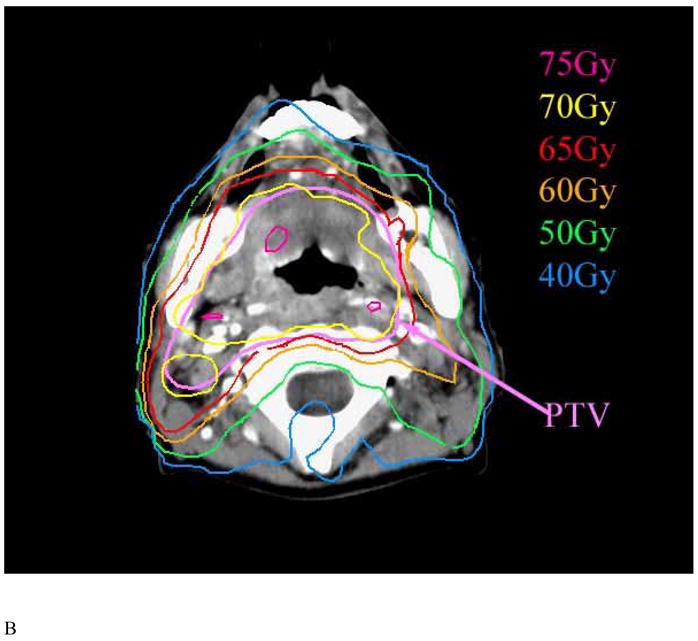

The mandibular DVHs generated for all available treatment plans are summarized in Figure 2. The mean (+/− SD) V50, V60, and V70 were 62% (+/−18%), 35% (+/− 20%), and 6.5% (+/−5%), respectively. No significant differences were found in the DVH parameters between patients treated with multisegmental or beamlet IMRT. The highest doses to at least 1% volume of the mandible is summarized in Figure 3. The mean mandibular volume was 58.8 cm3 (standard deviation, 14.4 cm3), such that on average 1% volume represents 0.59 cm3. More then 75% and 50% of the patients had a maximal dose of at least 65 Gy and 70 Gy to at least 1% of the mandibular volume, respectively. The treatment plans were characterized by dose gradients across the mandible: The average gradient across the mandibular bone, in an axial plane which included the maximal dose, was 11 Gy (range 1–27 Gy, median 8 Gy). This is illustrated in Figure 4: a patient treated with IMRT for a stage T3 N1 squamous cell carcinoma of the right tonsil and posterior pharyngeal wall. The primary PTV prescribed dose was 70 Gy and the dose fall-off across the mandible, perpendicular to the maximal dose delivered to the inner mandibular plate adjoining the PTV, was 21 Gy (72 Gy through 51 Gy).

Figure 2.

Combined cumulative DVH’s of the mandibule for all patients. The thick line represents the mean dose-volume and the vertical lines represent one standard deviation values.

Figure 3.

The distribution of maximum doses to 1% of the mandibular volume in individual patients.

Figure 4.

Axial CT slices at the levels of the mandibular angle (A) and rami (B) in a patient with tonsillar cancer demonstrating the dose fall-off from the buccal to the lingual surfaces of the mandible.

Dosimetry of the major salivary glands showed that the mean doses to the contralateral and ipsilateral parotid glands were on average 22 Gy (SD 5 Gy) and 53 Gy (SD 7 Gy), respectively, and the mean doses to the contralateral and ispsilateral submandibular glands were on average 57 (SD 8 Gy) and 65 Gy (SD 7 Gy), respectively. These doses resulted in significant sparing of the salivary flows from the contralateral parotid glands, which increased continuously during the first two years after the completion of therapy, as well as in improvements over time in patient-reported xerostomia. Results of the sialometry and xerostomia-related symptoms in the patients participating in this study were detailed elsewhere. 10,16–18

The median follow up was 35 months (range 6–129 months); of 148 patients still alive, 124 (70%) had at least 2 year, 82 (55%) had at least 3 year, and 47 (32%) patients had at least 5 years of follow-up.

Twenty-seven patients (15%) had local/regional disease recurrence, four of whom had also metastatic lung disease, and four had metastatic disease only.

No case with ORN was identified (95% Confidence Interval, 0; 2%). One patient had clinical suspicion for ORN due to local pain; however, no mandibular bone exposure was observed and panoramic x-ray demonstrated no bone changes. One patient had an asymptomatic transient mandibular bone exposure diagnosed during routine clinical exam, but panoramic x-ray of the jaws demonstrated no bone changes.

Discussion

The incidence of ORN following radiotherapy of HN cancer has declined in recent decades, from 11.8% before 1968 to 5.4% from 1968 to 1992, and further lower after 1997 to approximately 3% 1. The reduction in incidence of ORN occurred despite increasing intensity of therapy in recent years, such as concurrent chemo-RT and altered fractionated RT, which are characterized by increased acute side effects of therapy and occasionally by increased rates of late sequellae 19, 20. The reduction in recent years of ORN risk is reflected in our series, in which no case was observed among 176 patients, with a 95% confidence interval of 0; 2% (meaning that we cannot exclude a rate of ORN of up to 2% in patient populations similar to the sample we have studied). ORN is a late sequel and some cases may require long follow-up, however, the large majority of events have been reported to occur within 2 years after therapy (21). The low risk found in our series, in which 70% of patients were followed more than 2 years, is likely not related to a short follow-up. The reduction in the rates of ORN may be attributed to more conformal dose distributions which spared parts of the mandible which would have receive a high dose had conventional techniques been used, and to better prophylactic and on-going dental care. Of these two factors: dosimetric improvements and better dental care, which is the most important one?

While some patients in our series received a high maximal dose to the mandible, with half receiving 70 Gy or more, the mandibular volumes receiving a high dose were small (on average, V70 was 6.5%, which translates to about 4 cm3 out of an average mandibular volume of 60 cm3). Smaller volumes receiving high doses may have reduced the risk of bony exposure due to severe acute mucositis leading to consequential long-term damage. In addition to limiting the mandibular volumes receiving a high dose, the dose distributions in this series were characterized by a fall-off across the mandible, with the outer plate of the mandible across the “hot spot” receiving lesser doses. This dose fall-off might have implications regarding long-term effects on the local blood supply and its bone’s ability to withstand future trauma like teeth extractions. Not only has the total dose been limited, but in patients receiving a single IMRT plan, reduced total doses translated into reduced fraction doses, such that the biologically equivalent doses delivered to the parts of the mandible receiving less than 70 Gy were lower than their nominal doses would imply. For example, in a patient with maximal mandibular dose of 70 Gy delivered to the inner mandibular plate and a gradient of 11 Gy across the mandible (the average gradient in our series), delivered over 35 fractions, the nominal dose to the outer mandibular plate was 59 Gy delivered at 1.68 Gy/fraction. This is thought to be biologically equivalent to 55 Gy at 2 Gy/fraction, assuming a low alpha-beta ratio for late effects. In comparison, in a patient with oral or oropharyngeal cancer treated with conventional RT where the final boost is delivered to the gross disease using lateral opposed fields, the volume of the mandible receiving 70 Gy is expected to be much higher, with the high dose delivered to the full thickness of the mandible at the same fraction doses prescribed to the tumor.

Parliament et al. examined mandibular dose distributions in few IMRT cases and compared them to standard RT. They concluded that IMRT offers a dosimetric advantage if sparing the mandible is included in the plan optimization 22. In our series, reducing the mandible doses was achieved by constraints on both the maximal dose to the mandible and the mean dose to the non-involved oral cavity (which encompassed the mandible). The oral cavity mean dose constraint was enacted in order to reduce ORN risk and mucositis, as well as xerostomia, which was found in an earlier study to be affected by the mean oral cavity dose (which represented the potential damage to the minor salivary glands)10. In addition to reduced mandibular doses, the partial sparing of the salivary output achieved by IMRT may have reduced ORN risk through reduced teeth decay, a consequence of hyposalivation 23.

A clinical series concentrating on ORN in patients receiving IMRT has recently been reported by Studer et al.24 In this series, detailed dosimetry of the mandible showed small bone volumes receiving high doses, similar to our experience, and only one of 73 patients developed ORN. Other clinical series of IMRT for HN cancer reported a very low incidence of ORN25, and others did not include ORN as one of their late complications; it is not clear whether no cases were observed or ORN was not recorded in these series 26–28. However, IMRT and its dosimetric advantages may not guarantee a negligible risk of ORN. In a recent multi-institutional study of IMRT for early oropharyngeal cancer conducted by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), an ORN rate of 6% (in 4 out of 69 patients) was reported.30 In that study (RTOG study #HN 00–22) the prescribed high-risk PTV dose was 66 Gy in 30 fractions (2.2 Gy/fraction), and the mandibular maximal doses were limited to 72 Gy31. No major dosimetric violation of the protocol dose constraints occurred in the cases which developed ORN, however it is possible that the higher-than standard fraction doses delivered to part of the mandible adjacent to the PTVs may have played a role in the cases with ORN.

Another potential reason for the higher than expected incidence of ORN in RTOG 00–22 was the lack of standardized prophylactic dental care in that study. Guidelines for prophylactic dental care in this protocol were provided in a single sentence (“Any dental repairs must be made and prophylaxis instituted prior to therapy”) 31. Less-than-optimal prophylactic care was possible, especially in institutions treating small number of patients. This issue is reflected by the lack of any details of protocol dental care in publications which summarized the results of recent important clinical trials in head and neck cancer 32–37. This omission has been corrected in the most recent RTOG HN cancer protocols, which include appendices detailing recommended dental care. These recommendations, if adhered to, are expected to reduce the rates of ORN in multi-institutional studies to the very low rates reported by institutions treating large numbers of HN patients.

There is a controversy regarding some of the traditional dental care paradigms associated with the prevention of ORN. An extensive discussion of these controversies has recently been provided by Wahl 1. Extraction of healthy or restorable teeth before RT starts, practiced in past years, is not recommended any more and was not practiced in our patients, while extraction of decaying and non-restorable teeth has been a cornerstone of our prophylactic dental care. Prevention of ORN by hyperbaric oxygen in patients requiring post-RT teeth extraction is another contentious issue discussed at length by Wahl 1. Randomized studies of HBO vs. no HBO before post-RT teeth extractions showed significant benefits for the HBO arms, however the rates of ORN in the control arms seem to be higher than in other, non-randomized studies. In our series, two patients requiring post-RT teeth extractions from parts of the mandible which had received a high dose received HBO before extraction and four did not, and none developed ORN. Another common practice is the use of prophylactic antibiotics before post-RT teeth extractions, for which there is no firm evidence of efficacy1.

Apart from the controversies cited above, the principles of pre-RT prophylaxis include extraction of decaying or non-restorable teeth, strict dental care including daily topical fluoride and the use of dental protective stents to reduce scattered radiation off metal teeth restorations into the neighboring soft tissue, have been the cornerstone of the dental preventive care practiced in this series. We have found the latter device (detailed in Methods) to be effective in reducing acute mucositis in the soft tissue surrounding the restored teeth. The over-dosage due to backscatter off high-gold alloy was calculated to be 30% and 0 at 1 mm and 4 mm off the tooth, respectively38. Therefore, a thickness of 4 mm is required for the stent to minimize the increased dose to the soft tissue near the tooth. Reducing such “hot spots” around restored teeth may have contributed to reduced mucosal damage causing bony exposure and consequent ORN. In addition, the use of daily topical sodium fluoride gel application by a custom-made fluoride carrier has markedly reduced the risk of caries 39 and has been a routine practice in our institution. All patients received this device, and they were asked during follow-up visits as to whether they continued to use it routinely. However, details regarding the long-term compliance are not available, notwithstanding the costs of prescribed fluoride and lack of insurance coverage of these costs for many patients.

In conclusion, no cases of ORN were observed in this series of IMRT for HN cancer. The potential factors contributing to the lack of this complication include reduced mandibular volumes receiving high doses, improved salivary flow rates and associated improved oral health, and a uniform prophylactic dental care. We do not know which factor was most important. However, in the face of the reported occurrences of ORN in a multi-institutional study of IMRT in which a uniform dental care protocol was not applied, we suspect that the dental prophylactic care, as detailed in this paper, was a major factor reducing ORN risk. Meticulous dental care policies should be an integral part of the treatment of HN cancer.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH Grants CA059827 and K12 RR017607

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Notification: No conflicts of interest exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wahl MJ. Osteoradionecrosis prevention myths. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(3):661–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz HC, Kagan AR. Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: scientific basis for clinical staging. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25(2):168–71. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200204000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendenhall WM. Mandibular Osteoradionecrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(24):4867–4868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sciubba JS, Goldenberg D. Oral complications of radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:175–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisbruch A, Foote RL, O’Sullivan B, Beitler JJ, Vikram B. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: emphasis on the selection and delineation of the targets. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002;12(3):238–49. doi: 10.1053/srao.2002.32435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisbruch A, Marsh LH, Dawson LA, et al. Recurrences near base of skull after IMRT for head-and-neck cancer: implications for target delineation in high neck and for parotid gland sparing. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(1):28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisbruch A, Marsh LH, Martel MK, et al. Comprehensive irradiation of head and neck cancer using conformal multisegmental fields: assessment of target coverage and noninvolved tissue sparing. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41(3):559–68. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraass BA, Kessler ML, McShan DL, et al. Optimization and clinical use of multisegment intensity-modulated radiation therapy for high-dose conformal therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1999;9(1):60–77. doi: 10.1016/s1053-4296(99)80055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vineberg KA, Eisbruch A, Coselmon MM, McShan DL, Kessler ML, Fraass BA. Is uniform target dose possible in IMRT plans in the head and neck? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52(5):1159–72. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisbruch A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, Marsh LH, Dawson LA, Ship JA. Xerostomia and its predictors following parotid-sparing irradiation of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(3):695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisbruch A, Schwartz M, Rasch C, et al. Dysphagia and aspiration after chemoradiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: which anatomic structures are affected and can they be spared by IMRT? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(5):1425–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng F, Kim HM, Lyden T, et al. IMRT aiming at reducing dysphagia: Early dose-volume-effect relationships for the swallowing structures. Int J rad Onc Biol Phys; Presented at the 48th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO); Nov 2006; Philadelphia, PA. (abstract, in press) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein JB, Wong FL, Stevenson-Moore P. Osteoradionecrosis: clinical experience and a proposal for classification. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45(2):104–10. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marx RE. Osteoradionecrosis: a new concept of its pathophysiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41(5):283–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.http://ctep.canchttp://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf. http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf

- 16.Lin A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, et al. Quality of life following parotid-sparing IMRT of head and neck cancer: A prospective longitudinal study. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2003;57:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jabbari S, Kim HM, Feng M, et al. Quality of life and xerostomia following standard vs. intensity modulated irradiation: A matched case-control comparison. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2005;63:725–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meirovitz A, Murdoch-Kinch CA, Schipper M, et al. Scoring xerostomia by physicians vs. patients after IMRT of head and neck cancer. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.002. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starr S, Rudat V, Stuetzer H, et al. Intensified hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy limits the additional benefit of simultaneous chemotherapy: Results of a multcentric randomized German trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1161–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robbins K. Barriers to winning the battle with head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:4–5. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuther T, Schuster T, Mende U, Kubler A. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws as a side effect of radiotherapy of head and neck tumour patients- a report of a thirty year retrospective review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:289–295. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parliament M, Alidrisi M, Munroe M, et al. Implications of radiation dosimetry of the mandible in patients with carcinomas of the oral cavity and nasopharynx treated with intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34(2):114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kielbassa AM, Hinkelbein W, Hellwig E, Meyer-Luckel H. Radiation-related damage to dentition. The Lancet Oncology. 2006;7(4):326–335. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70658-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Studer G, Studer SP, Zwahlen RA, et al. Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: minimized risk profile following intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182(5):283–8. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Arruda FF, Puri DR, Zhung J, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for the treatment of oropharyngeal carcinoma: The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2006;64(2):363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee N, Xia P, Fischbein NJ, et al. Intensity modulated radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: The UCSF experience focusing on target volume delineation. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2003;57:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chao KSC, Ozygit G, Blanco AI, et al. Intensity modulated radiation therapy for oropharyngeal carcinoma: Impact on tumor volume. Int J rad Onc Biol Phys. 2004;59:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kam MKM, Teo PML, Chau RMC, et al. Treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma with intensity modulated radiotherapy: the Hong Kong experience. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 20 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauve A, Morris M, Schmidt-Ullrich R, et al. Simultaneous integrated boost intensity modulated radiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: II-clinical results. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2004;60:374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisbruch A, Harris Garden, et al. Phase II multi-institutional study of IMRT for oropharyngeal cancer (RTOG 00–22): Early results. Presented at the 48th Annual Meeting Of ASTRO; Philadelphis, PA. Nov 2006; Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys 2006 (abstract, in press) [Google Scholar]

- 31.www.rtog.org/members/active.html

- 32.Fu KK, Pajak TF, Trotti A, et al. A radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) phase III randomized study to compare hyperfractionation and two variants of accelerated fractionation to standard fractionation radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: first report of RTOG 9003. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2000;48(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dische S, Saunders M, Barrett A, Harvey A, Gibson D, Parmar M. A randomised multicentre trial of CHART versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1997;44(2):123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, et al. Postoperative Concurrent Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy for High-Risk Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR, et al. Hyperfractionated Irradiation with or without Concurrent Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(25):1798–1804. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806183382503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, et al. Postoperative Irradiation with or without Concomitant Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ang KK, Trotti A, Brown BW, et al. Randomized trial addressing risk features and time factors of surgery plus radiotherapy in advanced head-and-neck cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2001;51(3):571–578. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01690-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reitemeier B, Reitemeier G, Schmidt A, et al. Evaluation of a device for attenuation of electron release from dental restorations in a therapeutic radiation field. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:323–7. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.122506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horiot JC, Schraub S, Bone MC, et al. Dental preservation in patients irradiated for head and neck tumours: A 10-year experience with topical fluoride and a randomized trial between two fluoridation methods. Radiother Oncol. 1983;1(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(83)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]