Abstract

Background: The United States Preventive Services Task Force recently determined that they could not recommend any screening strategies for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Disparate findings in the literature and treatment-related problems have led to confusion about whether or not to screen for this disorder. The purpose of the present study was to determine, with use of expected-value decision analysis, which of the following three strategies leads to the best chance of having a non-arthritic hip by the age of sixty years: (1) no screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip, (2) universal screening of newborns with both physical examination and ultrasonography, or (3) universal screening with physical examination but only selective use of ultrasonography for neonates considered to be at high risk.

Methods: Developmental dysplasia of the hip, avascular necrosis, and the treatment algorithm were carefully defined. The outcome was determined as the probability of any neonate having a non-arthritic hip through the age of sixty years. A decision tree was then built with decision nodes as described above, and chance node probabilities were determined from a thorough review of the literature. Foldback analysis and sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results: The expected value of a favorable hip outcome was 0.9590 for the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography, 0.9586 for screening all neonates with physical examination and ultrasonography, and 0.9578 for no screening. A lower expected value implies a greater risk for the development of osteoarthritis as a result of developmental dysplasia of the hip or avascular necrosis; thus, the optimum strategy was selective screening. This model was robust to sensitivity analysis, except when the rate of missed dysplasia rose as high as 4/1000 or the rate of treated hip subluxation/dislocation was the same; then, the optimum strategy was to screen all neonates with both physical examination and ultrasonography.

Conclusions: Our decision analytic model indicated that the optimum strategy, associated with the highest probability of having a non-arthritic hip at the age of sixty years, was to screen all neonates for hip dysplasia with a physical examination and to use ultrasonography selectively for infants who are at high risk. Additional data on the costs and cost-effectiveness of these screening policies are needed to guide policy recommendations.

Level of Evidence: Economic and decision analysis Level II. See Instructions to Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip is a leading cause of early arthritis leading to total hip replacement1,2 and is the most common congenital defect in the newborn3, with an estimated incidence ranging from 1.4 to >35 per 1000 live births. Estimates of the incidence of developmental dysplasia of the hip depend, among other things, on the age of the neonate and the method used to detect the dysplasia3-6. Early detection through neonatal screening along with early initiation of treatment has lowered the rates of treatment-related complications such as avascular necrosis of the femoral head and neck7,8. Furthermore, neonatal screening can be performed by means of clinical examination9 or ultrasonography4,10,11; the tests themselves carry no risk to the patient. However, neonatal screening with ultrasonography will additionally identify many infants with abnormal findings in the hip that may completely resolve if left untreated3,12 (i.e., a “false-positive” ultrasound study). Hence, there remains a debate regarding the cost-effectiveness and efficacy of universal screening for hip dysplasia.

While the current Clinical Practice Guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening for hip dysplasia13-15, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recently concluded that “evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening” for developmental dysplasia of the hip6,16 because of the lack of clear scientific evidence favoring screening. The task force noted that they were “unable to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening” for developmental dysplasia of the hip6. This has sparked a debate in the literature about whether or not to screen for developmental dysplasia of the hip17-19. The key clinical questions are whether to screen for hip dysplasia, and if so, whether every infant should be screened with use of both physical examination and ultrasonography or with use of physical examination only, with ultrasonography being used selectively for infants at higher risk (those with a positive family history, breech presentation, or positive clinical examination).

Decision analysis is a methodological tool that allows quantitative analysis of decision-making under conditions of uncertainty20. It can be used to help to synthesize a large quantity of data into a logical algorithm. An expected value is determined for each decision. The expected value is the predicted consequence of the decision, based on the probability of each outcome and the probability consequence of that outcome.

The purpose of the present study was to determine, with use of expected-value decision analysis, which of three strategies leads to the best chance of having a hip that functions well and is pain-free at least to the age of sixty years: (1) no screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip, (2) universal screening of newborns with both physical examination and ultrasonography, or (3) universal screening of infants with physical examination but only selective ultrasonography for those considered to be at high risk.

Materials and Methods

Because of disparate definitions of developmental dysplasia of the hip and its treatment and complications, it is important from the outset to carefully delineate the definitions used in this analysis.

Definition of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip comprises a continuum that includes an immature hip, a hip with mild acetabular dysplasia, a hip that is dislocatable, a hip that is subluxated, and, finally, a hip that is frankly dislocated3,10. There is overlap between these states, but the treatment and treatment risks differ across this continuum. When developing an algorithm, definitions and delineations need to be made within the spectrum of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Hips with teratologic dislocations, including those resulting from myelodysplasia, arthrogryposis, chromosomal abnormalities, and dislocation due to cerebral palsy and skeletal dysplasia, were excluded because such hips respond differently to treatment, as documented in most of the literature on this topic21,22.

For the purposes of the present study, we differentiated between acetabular dysplasia and a dislocatable or subluxatable hip. Acetabular dysplasia, in the absence of dislocation or subluxation, is clinically silent (i.e., it is not evident on the Barlow or Ortolani screening maneuvers) and is typically categorized as Graf type II on ultrasonography. In the newborn infant, some hips can be mildly dysplastic; this condition likely will resolve, and therefore such hips are considered to be “immature” rather than truly dysplastic at this stage (in which case the finding of dysplasia may be considered to be a false-positive result). If this condition does not resolve by three months, then it is considered to be true acetabular dysplasia. It has been shown that >90% of cases of acetabular dysplasia (or hip immaturity) in the newborn will resolve without treatment12. In contrast, a dislocatable, subluxated, or dislocated hip is clinically apparent on Barlow and/or Ortolani screening and usually is categorized as Graf type III/IV on ultrasonography; these hips have clearer indications for imaging than do hips with only acetabular dysplasia. The natural history and treatment of hips that have acetabular dysplasia only and those that are subluxated or dislocated are different; therefore, we have defined them separately for the purposes of this analysis.

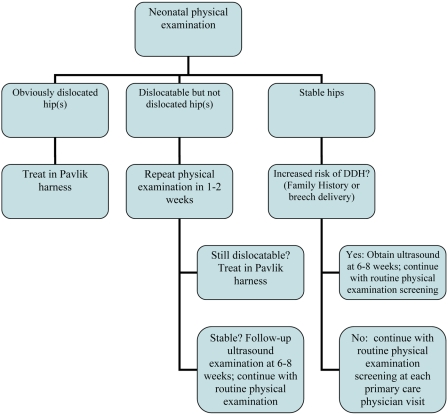

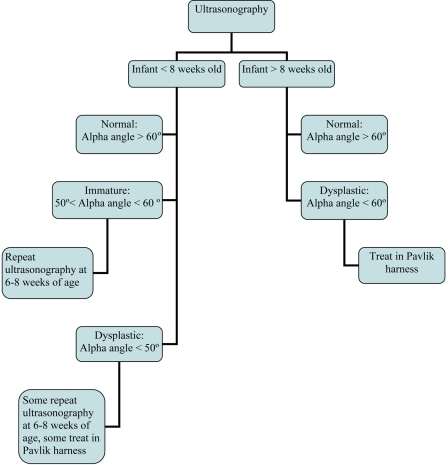

Treatment Algorithm

The treatment algorithm used in the present study was defined to be consistent with the current standard as practiced by most of the members of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA)23, the principal group treating developmental dysplasia of the hip in the United States. There remains, however, some variability in treatment from clinician to clinician. At the 2005 POSNA Annual Meeting, a “Specialty Day” focusing on developmental dysplasia of the hip was held, during which this treatment algorithm was developed23; this treatment algorithm also reflects the algorithm outlined originally by Graf10. In the treatment algorithm, obviously dislocated hips in the newborn are treated with use of a Pavlik harness and have clearer indications for imaging than do hips with isolated acetabular dysplasia. Dislocatable but not dislocated hips in the newborn undergo a repeat examination at one to two weeks. A newborn who has an ultrasound study showing immature hips will have a repeat ultrasound study at six to eight weeks; however, some pediatric orthopaedists use a Pavlik harness to treat dysplastic hips that have an alpha angle of <50° on ultrasonography (Figs. 1 and 2). The alpha angle is the angle between the edge of the convex portion of the osseous acetabulum and the ilium and represents the depth of the osseous acetabular coverage10. Infants with hips that have an alpha angle of >60° and >50% coverage of the femoral head on ultrasonography at the age of three months are considered normal23.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm of neonatal physical examination screening for hip dysplasia. DDH = developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm of ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Infants in whom the hips are initially dislocated or subluxated may be managed successfully with a Pavlik harness or may fail to achieve hip reduction in the harness. Hips that are successfully reduced may go on to be normal, may have persistent dysplasia, or may have development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Patients who are not managed successfully with a Pavlik harness typically undergo a surgical procedure, which may include closed or open reduction and femoral and/or pelvic osteotomies.

Screening Options

Three principal screening options are considered in this model, and these options are introduced into the model as decision nodes. In the no-screening option, all hip dysplasia is left undiscovered and untreated through childhood; that is, the outcome is the natural history of hip dysplasia. With this option, there are no risks of treatment of hip dysplasia, but there are no benefits of treatment either. With the second option, universal screening of all newborns with both physical examination and ultrasonography, all newborns are screened with these two methods shortly after delivery. The risk of this option is that a substantial number of infants with false-positive findings will receive treatment for a mild condition that would otherwise normalize on its own. The benefit of this option is that most or all dysplastic hips will be identified and treated in infancy. With the final option, universal screening with physical examination but only selective ultrasonography for infants who are considered to be at high risk, only neonates who have a positive physical examination or who have risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip (breech delivery and/or family history) receive screening with ultrasonography. The benefit is that fewer false-positive results will be identified and fewer infants will undergo unnecessary treatment. The risk of this option is that not all patients with hip dysplasia will be identified.

Major Complication of Treatment: Avascular Necrosis

The major complication of treatment is avascular necrosis of the femoral head and neck. This is thought to occur only with treatment and does not occur in hips that remain untreated24-26. Avascular necrosis may occur as a result of treatment with the Pavlik harness, with closed or open reduction, or with femoral or pelvic osteotomies27. The classification of avascular necrosis is fairly consistent in the literature as described by Kalamchi and MacEwen27. Grade-I avascular necrosis is characterized by changes only in the ossific nucleus, often with a delay in radiographic appearance. Grade-II avascular necrosis also is characterized by changes involving the lateral physis. Grade-III avascular necrosis is characterized by changes in the central physis. Grade-IV avascular necrosis involves the entire head and neck. Grade-II, III, and IV avascular necrosis may lead to long-term sequelae, progressive hip symptoms, and early degeneration of the hip. However, Grade-I avascular necrosis consistently has been shown not to lead to long-term sequelae21,24-27. As Grade-I avascular necrosis is inconsequential, only Grades II, III, and IV were utilized when determining rates of avascular necrosis for the present study.

Definition of Outcome and Outcome Utilities

The goal of treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip is to reduce the long-term risk of early arthritis and to optimize the number of hips that are normal at maturity. As osteoarthritis is the end result of untreated hip dysplasia, incompletely treated hip dysplasia, and the complications of treatment, it is the final common pathway and can be used as the outcome for the decision analysis. The modified Severin classification system28-30 is an intermediary outcome measure that is correlated with the eventual development of arthritis. A Severin class-I hip is normal, with a center-edge angle of >20°. A Severin class-II hip has moderate deformity of the head, neck, or acetabulum in an otherwise well-developed joint, with a center-edge angle of >20°; a Severin class-III hip is dysplastic but not subluxated, with a center-edge angle of ≤20°; and a Severin class-IV hip is subluxated, with a center-edge angle usually of much less than 20°. The Severin classification is applied at skeletal maturity on the basis of the radiographic appearance of the hip21,31,32. This classification system has fair to moderate reliability (an interobserver kappa statistic of 0.19 to 0.54 and an intraobserver kappa statistic of 0.66 to 0.85)33 and is predictive of early arthritis32. In order to reflect the gradations commonly found in the literature, in the present study the classifications were combined as Severin class I/II and Severin class III/IV, which likely improved the interobserver reliability. Albinana et al. found the risk of end-stage arthritis to be 7% for Severin class-I/II hips, 29% for Severin class-III hips, and 49% for Severin class-IV hips32. As Severin classes III and IV are often combined in studies and cannot be separated, their average value (approximately 40%; i.e., the combined average of the risk of end-stage arthritis for Severin class-III and Severin class-IV hips) is utilized for the purposes of this analysis. The rate of baseline moderate-to-severe hip arthritis for individuals without developmental dysplasia of the hip is 3% to 4%2,34,35.

The outcome for this decision analysis is the probability of not having severe arthritis before the age of sixty years (pOA), which is related to the risk of having early arthritis before the age of sixty years (1 − pOA). For a child without residual developmental dysplasia of the hip or avascular necrosis, the risk of arthritis before the age of sixty years is 4% and the chance of having a non-arthritic hip is 96%. For a child with a Severin class-I/II hip at maturity, the risk of early arthritis is 7%, and the chance of having a non-arthritic hip is 93%. For a child with a Severin class-III/IV hip at maturity, the risk of early arthritis is 40%, with a 60% chance of having a non-arthritic hip, with variability in the literature ranging from 35% to 100%25,30,36.

Statistical Methods

The Decision Tree

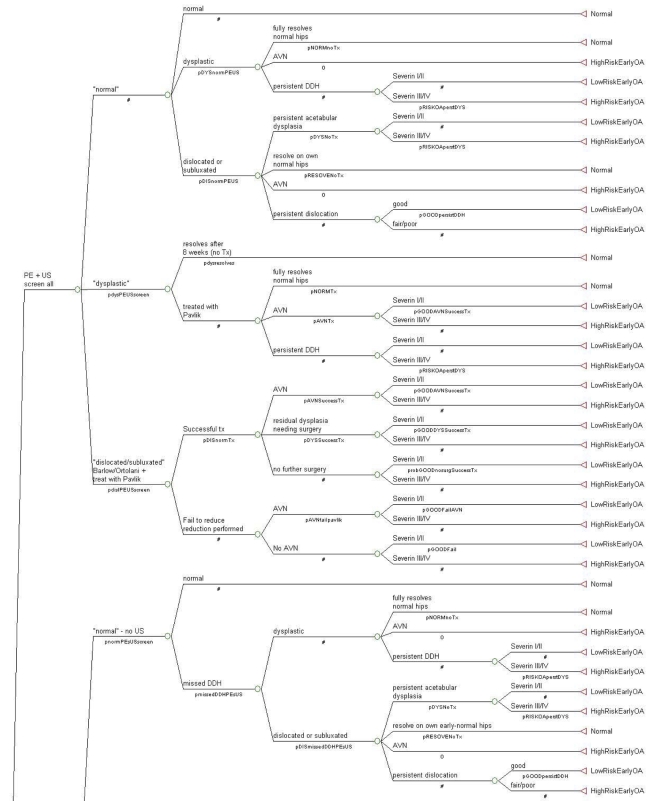

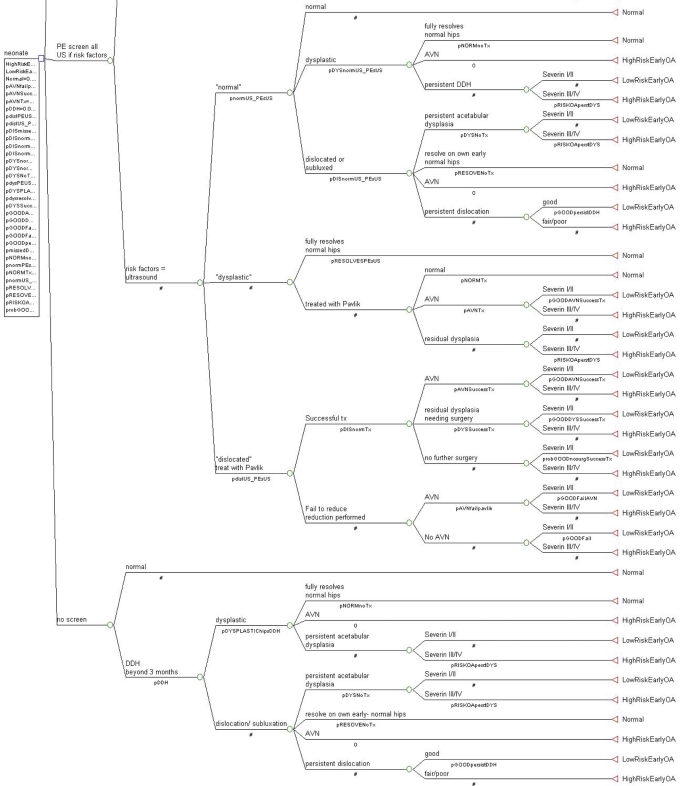

TreeAge Pro 2007 (Williamstown, Massachusetts) was utilized for the data tree analysis. The decision tree was built with three decision nodes: (1) screening of all neonates with physical examination and ultrasonography, (2) screening of all neonates with physical examination but use of ultrasonography only for those with risk factors (breech delivery or family history) or a positive physical examination, and (3) no screening. Then, the probability of a positive test, adjusted for accuracy, and the probability of developmental dysplasia of the hip were added to the model at chance nodes; these probabilities included false-positive, false-negative, true-positive, and true-negative data for the ultrasonography test. Characteristics for the four treat/no-treat options were then incorporated; these options included (1) treatment for acetabular dysplasia, (2) no treatment for acetabular dysplasia, (3) treatment for dislocation/subluxation, and (4) no treatment for dislocation/subluxation. Figure 3 shows the final tree.

Fig. 3.

The decision-analysis tree. A table in the Appendix lists the identifying codes, associated descriptions, probabilities, and literature references. A number sign (#) denotes calculating the probability for that node by subtracting the values of the other nodes on that branch from the value of 1.0.

The probabilities for each chance node were based on the literature (as discussed below). Foldback analysis was then utilized to determine the weighted average of the outcome probabilities multiplied by the outcome utilities. The resultant expected values were then used to determine the optimum decision. In this analysis, the expected values constituted the probability of each newborn not having early hip arthritis due to developmental dysplasia of the hip and/or avascular necrosis. Given the assumption that 4% of newborns with no hip problems would have development of hip arthritis by the age of sixty years, the maximum possible expected value in this analysis is 96%.

Literature Review

As there are a large amount of data on developmental dysplasia of the hip3,6, a systematic review of the literature was undertaken to acquire the most appropriate data for this analysis. Information was acquired from PubMed searches, literature citations, and clinical practice guidelines. Clinical trials were utilized when available; as these data are considered more powerful than data from retrospective reviews, they were given additional weight. There were only two randomized clinical trials in which screening of all newborns with physical examination and ultrasonography was compared with screening of all newborns with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography for those with positive risk factors or clinical examination findings12,37. No randomized clinical trials compared screening with no screening. Studies with clinical algorithms that were consistent with our treatment plan were used when available. Many older studies had a different treatment algorithm and were therefore difficult to include. Long-term data reflecting rates of arthritis were also found and used.

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to model the effect on expected values of variations in certain probabilities. Sensitivity testing and multi-way sensitivity analysis was also done on other probabilities to evaluate the robustness of the model.

Because of the variability in the rate of avascular necrosis for hips that were subluxated or dislocated and treated both unsuccessfully and successfully with a Pavlik harness, sensitivity analyses were performed to incorporate the ranges that were found. Because the false-positive rate of ultrasound has been reported to be as high as 20%, sensitivity analysis was done around this result as well. The natural history of spontaneous reduction of hip subluxation or dislocation is not fully understood; therefore, a sensitivity analysis was done around this variable also.

In both clinical trials in which physical examination and universal ultrasound screening was compared with physical examination and selective ultrasound screening, the rate of missed dysplasia in the selective-screening group was lower than had been seen in previous analyses12,37. In Norway, prior to the clinical trials, the rate of missed developmental dysplasia of the hip associated with physical examination screening of all infants and selective use of ultrasound for those with risk factors or positive clinical findings was 3/100012. However, a rate of 1.3/1000 was found in the clinical trial by Rosendahl et al.12 and a rate of 0.65/1000 was found in the trial by Holen et al.37. As the rate of 1.3/1000 was used in the decision tree, a sensitivity analysis was done to assess what would happen to the results if this rate reached standard values.

In the clinical trial that was utilized for the probability that a hip was subluxated or dislocated, there was a higher rate of hip subluxation or dislocation in the group that underwent physical examination and universal ultrasound screening (25/1000) as compared with the group that underwent physical examination and selective ultrasound screening (18/1000)12. As this finding should be apparent on physical examination, the disparity was unexpected; however, when the ultrasonography findings revealed Graf type-III/IV dysplasia, a repeat physical examination often demonstrated the subtle clinical findings12.

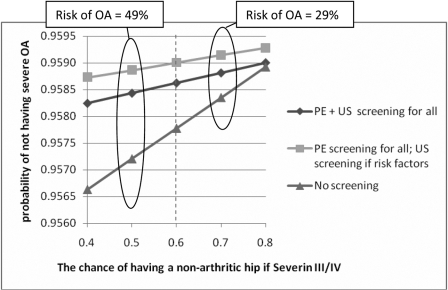

Sensitivity analyses were also done surrounding the main outcome variable, the rate of end-stage arthritis in hips that are Severin class III/IV at the end of adolescence. The baseline rate of early arthritis of 40% was based on data from the study by Albinana et al.32, in which the rate of severe early arthritis was 7% for Severin class-I/II hips, 29% for Severin class-III hips, and 49% for Severin class-IV hips. As most follow-up data in other studies combined Severin class-III and IV hips21,31,38,39, we were obliged to do the same, and the average baseline rate of early arthritis for Severin class-III/IV hips was set to 40% (or, in the algorithm, a 60% chance of a non-arthritic hip). Other studies also provided rates of early arthritis with residual dysplasia25,36.

Outcome Probabilities

The outcome probabilities for screening with physical examination and ultrasonography, screening with physical examination and selective ultrasonography, and no screening are listed in a table in the Appendix.

Rates of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip with Screening. The two randomized clinical trials in which physical examination and ultrasound screening of all infants was compared with physical examination and selective ultrasound screening provided probabilities for the rates of detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip12,37. In one trial12, the physical examination and ultrasound screening of all infants had a probability of treatment of 13/1000 for acetabular dysplasia and of 25/1000 for dislocation or subluxation. In the same trial, the combination of physical examination and selective ultrasound screening had a probability of treatment of 0.3/1000 for acetabular dysplasia and of 18/1000 for dislocation or subluxation. The rate of missed developmental dysplasia of the hip in the selective-screening group was 1.3/1000, compared with the pre-study rate of 2.6/100012.

Rates of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip with No Screening. In the no-screening group, the probability of having developmental dysplasia of the hip was based on generally recognized values of 11.5/1000 for hip dislocation and subluxation and an additional 13.5/1000 for acetabular dysplasia13. These values range from 1.4/1000 to >35/1000 when ultrasound screening is utilized4,12,40-42 and may be as high as 20% in certain populations3-6,26. It was recognized in the model that dysplasia that is left untreated frequently corrects over time, giving a true dysplasia rate of closer to 5/100038. Probabilities for the resolution of untreated hip dislocation or subluxation were determined in a study on Navajo people43. Coleman reported that 22% of hips with untreated dislocation or subluxation had spontaneous resolution, whereas 39% had residual acetabular dysplasia and 39% had persistent dislocation43. Despite persistent dislocation, pain and arthritis were absent in 41% of the hips, and these were considered to have a “good” outcome. The probability that residual acetabular dysplasia after the age of one year leads to or increases the risk of early arthritis varies. Albinana et al.32 reported that 78% of dislocated dysplastic hips at twelve months were Severin class I/II at maturity, whereas Gotoh et al.31 found that only 68% of such hips were Severin class I/II at maturity; others have found this percentage to be much higher30,36.

Rates of Success with Pavlik Harness Treatment. Pavlik reported a successful hip reduction rate of 84% in association with the use of the harness44, which is comparable with the rate of 86% found in a multicenter study by the European Paediatric Orthopaedic Society45. Overall, studies in the literature have demonstrated rates of successful results ranging from 82% to 99%8,21,22,45-51.

Rates of Avascular Necrosis. Avascular necrosis rates depend on both the underlying diagnosis and the treatment. As avascular necrosis is an iatrogenic complication, it does not develop in patients with untreated developmental dysplasia of the hip24-26. In patients managed for acetabular dysplasia only, the highest rate of avascular necrosis found in the literature was 1.3%45 (range, 0% to 1.3%); most authors have reported no avascular necrosis in association with the treatment of acetabular dysplasia22,44,45,50,52-54. For this decision analysis, the rate of avascular necrosis associated with the treatment of acetabular dysplasia with a Pavlik harness was set at 1%. For the treatment of hip dislocation or subluxation, the rates of avascular necrosis tend to be higher. The rate also depends on whether the hip was successfully reduced in the Pavlik harness or additional procedures were necessary45. The surgical procedures and their probabilities for avascular necrosis are combined in this model under the category of “failure to reduce” in the harness. The risk of development of avascular necrosis in association with the treatment of hip dislocation and subluxation gets considerably higher as the patients get older6,21,46,48. Patients who were managed successfully with a Pavlik harness for the treatment of hip dislocation or subluxation had a rate of avascular necrosis that ranged from 0% to 12.3%, with all but three studies demonstrating a rate of <3%8,21,22,31,44-50,52-56. Infants who were not successfully managed with a Pavlik harness and needed other procedures had a higher rate of avascular necrosis38,45. Traction is no longer part of the treatment protocol23,38,45. Rates of avascular necrosis (other than type I) resulting from closed or open reduction after the failure of treatment of hip subluxation or dislocation with a Pavlik harness ranged from 3% to 52%38,45, and the higher rate was in infants who were managed with reduction at an average age of twenty-one months, which is older than is accommodated for in the treatment algorithm38. For this decision analysis, the rate of avascular necrosis for hips that were subluxated or dislocated and were successfully treated with a Pavlik harness was 2% and the rate for those in which other methods were necessary to achieve reduction was set at 3% to reflect the bulk of the literature.

Best-Case Analyses. In order to assess how the variability of the multiple probabilities potentially influences the model, we went ahead with a “best case for screening” analysis and a “best case for no screening” analysis. In the “best case for no screening” analysis, the chance that osteoarthritis would not actually develop in a hip that was considered to be at high risk for osteoarthritis was set to its highest value, the rate of avascular necrosis was set to its highest value, the rate of false-positive ultrasonography diagnoses was set to its highest value, the probability that a hip would become normal if acetabular dysplasia was not treated was set to its highest value, the rate of spontaneous reduction of hip subluxation or dislocation was set to its highest value, and the probability that a person with persistent acetabular dysplasia is at high risk for early osteoarthritis was set to its lowest value. In the “best case for screening” analysis, the chance that osteoarthritis would not actually develop in a hip that was considered to be at high risk for osteoarthritis was set to its lowest value, the rate of avascular necrosis was set to its lowest value, the rate of false-positive ultrasonography diagnoses was set to its lowest value, the probability that a hip would become normal if acetabular dysplasia was not treated was set to its lowest level, the rate of spontaneous reduction of hip subluxation or dislocation was set to its lowest value, and the probability that a person with persistent acetabular dysplasia is at high risk for early osteoarthritis was set to its highest value.

Source of Funding

There was no external source of funding for this study.

Results

Expected Values

The expected value for the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and ultrasonography was 0.9586 (or a 95.86% chance of avoiding severe arthritis before the age of sixty years), whereas the expected value for the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography was 0.9590 (95.90%) and the expected value for the strategy of no screening was 0.9578 (95.78%). In this case, the expected value corresponds with the probability at birth that any given infant will have arthritis-free hips as an adult. A smaller expected value constitutes a greater risk of osteoarthritis resulting from developmental dysplasia of the hip and/or avascular necrosis. The result given by our decision analysis favors the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography for those with risk factors or positive physical examination findings.

Given that 4% of infants go on to have hip arthritis irrespective of the status of the hips in infancy, the likelihood that an individual will have hip arthritis by the age of sixty years because of developmental dysplasia of the hip is equal to 0.96 minus the expected value. That risk was 0.014 for the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and ultrasonography, 0.010 for the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography, and 0.022 for the strategy of no screening.

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the model. When the rate of avascular necrosis in successfully treated hips ranged from 1% to 12.3%, the optimum strategy (that is, the strategy with the greatest expected value) was still to screen all neonates with physical examination and to use ultrasonography selectively for those with risk factors. With the rate of avascular necrosis in successfully treated hips set to 12.3% (the highest rate) and the rate of avascular necrosis in hips that had a failure of Pavlik treatment set to range between 3% and 52%, the optimum strategy did not change and the expected value was still greatest for selective screening. Thus, the expected value was not sensitive to variations in the rates of avascular necrosis with treatment.

The rates of ultrasonographic diagnosis of subluxation, dislocation, and pure acetabular dysplasia of the hip were adjusted to vary around 20% of their respective probabilities. Decreasing the false-positive rate for hips that are subluxated or dislocated (in addition to changing the reliability of the diagnosis for those with pure acetabular dysplasia) did increase the expected value (or probability of a good outcome) for the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and ultrasonography and the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography; similarly, increasing the false-positive rate decreased the expected value for both strategies. However, this finding did not change the hierarchy of the optimum screening strategy of the model.

The probability that hip dislocation or subluxation would resolve on its own without treatment initially was set at 22% on the basis of a study involving Navajo people43. For the sensitivity analysis, the rate of spontaneous resolution ranged from 10% to 60%. The greatest expected value and optimum strategy across this entire range of probabilities still favored the strategy of universal physical examination screening and selective ultrasonography screening.

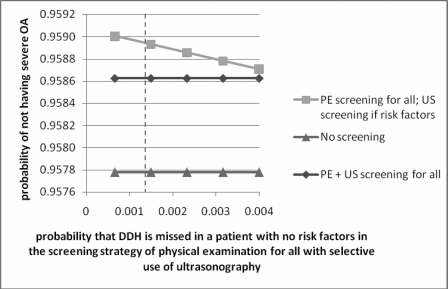

The rate of missed dysplasia for the strategy of screening all neonates with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography was adjusted to range from 0.65/1000 to 4/1000 in a one-way sensitivity analysis, and again no difference in the optimum strategy was found (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Graph showing the results of sensitivity analysis performed by varying the probability of missing developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) in infants with no risk factors when using the strategy of physical examination screening for all infants and selective ultrasonography for those at high risk. The vertical dashed line represents the value used in the model. PE = physical examination, US = ultrasonography, and OA = osteoarthritis.

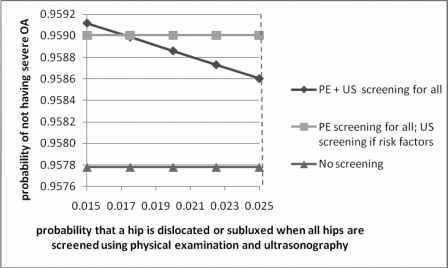

A sensitivity analysis was performed around the rate of hip subluxation and dislocation for the strategy of screening all patients with physical examination and ultrasonography; when the rate of hip subluxation or dislocation associated with the strategy of physical examination and universal use of ultrasonography reached the same as that associated with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography (18/1000), the optimum strategy was to screen all with both physical examination and ultrasonography (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Graph showing the results of sensitivity analysis performed by varying the probability of identifying a dislocated or subluxated hip when using the strategy of screening all infants with both physical examination and ultrasound. The vertical dashed line represents the value used in the model. PE = physical examination, US = ultrasound, and OA = osteoarthritis.

Because of some uncertainty in the main outcome variable of the chance of development of early arthritis for Severin class-III/IV hips, a sensitivity analysis was performed in which the chance of a non-arthritic hip was varied from 40% to 80%. Even with this wide variation in the rate of early arthritis of the hip in those with residual deformity, the hierarchy of the expected value did not change. As the chance of having a non-arthritic hip decreased, the no-screening option got worse in comparison with both screening options. Similarly, as the chance of having a non-arthritic hip increased, the no-screening option got closer to (but never got better than) the screening options (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Graph showing the results of sensitivity analysis performed by varying the outcome variable of the rate of end-stage arthritis by the age of sixty years in patients who have a Severin III/IV hip at the end of adolescence. The vertical dashed line represents the value used in the model. OA = osteoarthritis, PE = physical examination, and US = ultrasonography.

Best-Case Analysis

In the “best case for no screening” analysis, the no-screening strategy was found to be optimum, with an expected value of 0.9597. The strategy of screening all with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography had an expected value of 0.9590, whereas the strategy of screening all with both physical examination and ultrasonography had an expected value of 0.9586.

In the “best case for screening” analysis, the strategy of screening all with physical examination and selective use of ultrasonography was found to be optimum, with an expected value of 0.9588. The strategy of screening all with both physical examination and ultrasonography had an expected value of 0.9584, and the no-screening strategy had an expected value of 0.9534.

Discussion

There has been a long-standing debate on how best to screen for developmental dysplasia of the hip. This discussion has generally compared physical examination screening with universal ultrasonography screening4,39,42,53,57-62. Some studies have supported universal screening10,50,63, and others have supported physical examination screening with only selective use of ultrasonography57,64. While a few investigators have recommended universal screening with ultrasound, the United States Preventive Services Task Force, on the basis of its own systematic review of the literature, could not recommend even clinical examination screening, although developmental dysplasia of the hip is a leading cause of early hip arthritis6,16.

Almost all authors have agreed that the earlier a patient receives treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip, the better the outcome6-8,38,39,65. A higher rate of avascular necrosis is found in older patients, and often the treatment is more invasive, which supports earlier screening for and identification of developmental dysplasia of the hip38. In several studies, screening with clinical examination alone has been found to reduce the rate of, but not to eliminate, late-presenting developmental dysplasia of the hip39,61,66-69. The United States Preventive Services Task Force consensus finding that they were “unable to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening” for developmental dysplasia of the hip6 speaks to the complexity of the problem and a large amount of data as well as the lack of natural history comparison studies3, and this position has been very concerning to some of those who treat this problem18.

Decision analysis is a powerful technique that can systematically evaluate a complicated problem. It is able to synthesize a vast array of input parameters and to provide chance nodes with varying probabilities around which sensitivity analyses can be done20. Our model showed that the expected probability of having a non-arthritic hip by the age of sixty years was highest in association with the strategy of performing physical examination for all infants and selective ultrasonography screening for those with risk factors, including an abnormal physical examination (95.90%). In comparison, the expected probability of having a non-arthritic hip by the age of sixty years was 95.86% for the strategy of using ultrasound screening for all infants and 95.78% for the no-screening strategy. While there was some overlap between the selective and universal ultrasonography screening strategies, at no point in the sensitivity analyses was the no-screen option found to be optimum.

In the best-case analyses, it was not surprising to find that, in the “best case for no screening” situation, the no-screening strategy was found to be best. In the “best case for screening” situation, the strategy of screening all with physical examination and selective screening with use of ultrasonography was again the best; its overall expected value was lower than in the original model because each hip that was Severin class III/IV at maturity provided a much lower expected value, bringing down the average expected value for the strategy. However, the disparities between the strategies in the “best case for screening” were much higher than in the “best case for no screening.”

It was surprising to find that varying the rate of avascular necrosis did not change the optimum screening strategy. However, whereas not all developmental dysplasia of the hip leads to early arthritis, similarly, not all avascular necrosis leads to early arthritis31,38. Because some hips with avascular necrosis are not at risk for early arthritis, the effect of avascular necrosis on the optimum screening strategy is blunted.

The false-positive rate associated with ultrasonography can vary considerably, largely on the basis of the age of the patient when ultrasonography is done. Ultrasonography identifies developmental dysplasia of the hip (including hip immaturity) in 22% of all neonates when the strategy of screening all patients with physical examination and ultrasonography is used, and >90% of these hips become normal if untreated, a finding that is included in the model. The false-positive rate seen in association with ultrasonography largely affects the population with pure acetabular dysplasia. While some of the hips that are diagnosed as subluxated or dislocated with use of ultrasonography do correct on their own, this percentage is substantially lower. The rate of treatment-related complications, including avascular necrosis following the treatment of pure acetabular dysplasia, was set at 1% in the current model; altering the reliability of the ultrasound diagnosis by 20% did not impact the optimum screening strategy of the model.

It is somewhat counterintuitive that the strategy of using ultrasound screening for all infants was not the best option. However, as there was a higher rate of hip subluxation and dislocation in the clinical trial that provided the data for the universal ultrasound strategy (25/1000 as compared with 18/1000 for the selective ultrasound strategy), this reflects some of the difference (as seen in the sensitivity analysis around this number). There was also a higher proportion of immature hips treated in the universal ultrasound group (in which a total of forty-eight hips were treated for dysplasia) as compared with the selective ultrasound group (in which a total of fourteen hips were treated for dysplasia). The benefits of identifying a few more infants with acetabular dysplasia are outweighed by the complications associated with the higher rate of treatment. Ultrasonography can detect developmental dysplasia of the hip that is not found with clinical examination3,10,62, and it therefore would be expected that a higher rate of late-presenting dysplasia would be found in association with the strategy of selective ultrasound screening. While this was the case, the rate was not significantly higher12,37. This higher rate of treatment then becomes part of the tree with use of a different set of studies with higher rates of treatment-related problems, leading to a lower expected value for the strategy of universal ultrasound screening.

Does the small difference among the three expected values matter? If the expected value for a non-arthritic hip that is treated optimally with physical examination screening and selective use of ultrasound screening is 95.90%, is that rate substantially different from the expected value of 95.78% for a non-arthritic hip that is treated with no screening? The sensitivity analyses assessed the robustness of the analyses20, and this model was found to be robust to sensitivity analysis. Furthermore, in this case, screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip is a population-wide assessment, and this needs to be taken into account when deciding if this difference matters. In the United States in 2005, there were 4,140,419 live births70. While there are some nondifferential life-expectancy issues that would mean that not everyone who is born will potentially be impacted by early hip arthritis, the difference in expected value between the selective ultrasound strategy and the universal ultrasound strategy would mean that 1656 fewer infants born in 2005 would have development of arthritis if the selective screening strategy was used instead of the universal screening strategy. Similarly, a comparison between the no-screening option and the selective screening option indicates that 4969 fewer infants born in 2005 would have development of early severe hip arthritis if the selective screening strategy was used instead of the no-screening strategy. There is, however, some variability in the model because of the uncertainty of the outcome parameters, which would influence the magnitude of this burden of early hip arthritis.

Other authors have used decision analysis to address this question, although not in quite the same way. The Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Academy of Pediatrics was a decision-analysis project that examined the treatment algorithm in a Markov model-type process13,64. Hernandez et al.71 used decision analysis to compare universal ultrasound screening with physical examination screening, with use of utilities as an outcome, and also found physical examination screening to be the best option.

Physical examination is known to be somewhat unreliable, with some variability in its ability to detect developmental dysplasia of the hip3,6,12,72. This variability may be considered to be a weakness of the present study, resulting in false-positive or false-negative results. However, in our model, this variability was taken into account with the use of data from a randomized clinical trial comparing physical examination screening with ultrasound screening12. That trial utilized different physicians performing the physical examination screening, which, as closely as possible, is similar to the variability that physicians in the United States would likely have when performing the same physical examination screening. Thus, the issue of false-positive and false-negative results was addressed in the present study, and these data were utilized in the model.

We set the initial rate of developmental dysplasia of the hip in the unscreened population to the generally recognized value of 25/10006. Admittedly, this rate of developmental dysplasia of the hip is based on an ultrasonographic diagnosis at the age of approximately three months, and it decreases naturally over time if untreated. Bialik et al.41 reported that the “true” prevalence of developmental dysplasia of the hip necessitating treatment is 5/1000. This has been reflected in the model as 80% of dysplastic hips fully resolve by the age of one year; half of the other 20% resolve by skeletal maturity (with sensitivity analysis around that latter number from 22% to 75% showing no difference in optimal treatment strategy). Similarly, of the hips that are subluxated or dislocated, 22% fully resolve by the age of one year, 39% go on to persistent dysplasia (with 50% of those resolving by skeletal maturity), and the other 39% of hips that are initially subluxated or dislocated remain so (but >40% of those are not at high risk for early arthritis). This would set the model adult population at 2.3/1000, which is on par with the clinically noted rate of 2/1000 in the adult population that is found to have early osteoarthritis.

In this model, the no-screening strategy is considered to represent the natural history of untreated developmental dysplasia of the hip. Without screening, developmental dysplasia of the hip goes untreated until the patient has end-stage arthritis. It is also not clear in the United States Preventive Services Task Force report what was meant by “no screen.”6 While in the real world, some unscreened hips undoubtedly would be discovered to have developmental dysplasia and would be treated at some point during development, it is impossible to predict the age at which and the frequency with which these hips would be identified. Furthermore, the identification of those hips would be due either to screening (i.e., fortuitous finding on radiographic or physical examination) or to symptoms indicative of early arthritis. Because of this difficulty and unpredictability, we have left the no-screening strategy to reflect the natural history of hip dysplasia that is left untreated throughout childhood.

There are some valid concerns with modeling, and our results should be considered with this in mind20. In modeling, data are obtained from many sources, and this is perhaps especially true in this analysis. We found it necessary to combine data from different studies to give us the best picture of the lifetime risks; e.g., one study provided the risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip to skeletal maturity on the basis of the Severin classification and another study provided the risk of early arthritis on the basis of the Severin classification. Unfortunately, no study followed participants from birth until the age of sixty years; such a study may be invaluable for determining the optimum answer to this question. However, the results of such a study would be a generation away, and in the meanwhile we need to determine how best to detect developmental dysplasia of the hip. While the data used for the present analysis are admittedly suboptimum, they are the only data available to us. Decision analysis is the best tool that we have for utilizing the available data to try to address such a complicated and difficult question. There are varying degrees of bias present in each study that we utilized because of potential confounding, patient selection, or method of analysis. There can also be assumptions in the model that can bias it in favor of, or against, a particular strategy; extensive sensitivity analysis of the model parameters can help to address those concerns20.

Decision analysis compares the health benefits of management strategies without regard to costs. Cost-effectiveness analysis includes the cost of health benefits. While this is an important component of any screening assessment, in the present study, the first priority was to determine how to maximize the number of non-arthritic hips. Adding costs to this model, particularly over a sixty-year time frame, would increase the variability tremendously, which we wish to avoid at this time. We anticipate that possible subsequent analyses using this model will be performed to assess the trade-offs between the effectiveness of screening strategies and their costs. Decision analysis by itself, in the absence of cost analysis, should not be utilized for policy recommendations because policy decisions require assigning priority to one program at the expense of another. Such decisions require a comparison of trade-offs between resource costs and health benefits.

In summary, our model leads to a recommendation for physical examination screening for all newborns and selective use of ultrasonography for those with a positive physical examination, breech delivery, and/or a positive family history of developmental dysplasia of the hip. While we recognize the limitations inherent in the decision-analysis process, it may be the best way to help determine the balance between the risks and benefits of screening for hip dysplasia. Long-term comparison studies between screening methods would take decades for results, and the equipoise may be difficult to achieve.

Appendix

A table showing the various outcome probabilities used in this study is available with the electronic versions of this article, on our web site at jbjs.org (go to the article citation and click on “Supplementary Material”) and on our quarterly CD/DVD (call our subscription department, at 781-449-9780, to order the CD or DVD).

Disclosure: In support of their research for or preparation of this work, one or more of the authors received, in any one year, outside funding or grants in excess of $10,000 from the National Institutes of Health (#K24 AR02123 and #P60 AR47782), the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation, and Siemens Medical Solutions. Neither they nor a member of their immediate families received payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, division, center, clinical practice, or other charitable or nonprofit organization with which the authors, or a member of their immediate families, are affiliated or associated.

Investigation performed at Children's Hospital Boston, Boston, Massachusetts

References

- 1.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;213:20-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1343-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kocher MS. Ultrasonographic screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: an epidemiologic analysis (part I). Am J Orthop. 2000;29:929-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound in the early diagnosis of congenital dislocation of the hip: the significance of hip stability versus acetabular morphology. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel H; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Preventive health care, 2001 update: screening and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. CMAJ. 2001;164:1669-77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shipman SA, Helfand M, Moyer VA, Yawn BP. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: a systematic literature review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e557-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gage JR, Winter RB. Avascular necrosis of the capital femoral epiphysis as a complication of closed reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip. A critical review of twenty years' experience at Gillette Children's Hospital. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:373-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshitaka T, Mitani S, Aoki K, Miyake A, Inoue H. Long-term follow-up of congenital subluxation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:474-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barlow TG. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44:292-301. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graf R. Fundamentals of sonographic diagnosis of infant hip dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4:735-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graf R. New possibilities for the diagnosis of congenital hip joint dislocation by ultrasonography. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3:354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in the neonate: the effect on treatment rate and prevalence of late cases. Pediatrics. 1994;94:47-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 1):896-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann HP, Hinton R, Morello P, Santoli J. Developmental dysplasia of the hip practice guideline: technical report. Committee on Quality Improvement, and Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg M. Early detection of developmental hip dysplasia: synopsis of the AAP Clinical Practice Guideline. Pediatr Rev. 2001;22:131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117:898-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calonge N, Petitti D. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: in reply. Pediatrics. 2007;119:653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoenecker PL, Flynn JM. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatrics. 2007;119:652-3; author reply 3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storer SK, Skaggs DL. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1310-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuntz KM, Weinstein MC. Modelling in economic evaluation. In: Drummond MF, McGuire A, editors. Economic evaluation in health care: merging theory with practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. p 141-71.

- 21.Nakamura J, Kamegaya M, Saisu T, Someya M, Koizumi W, Moriya H. Treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip using the Pavlik harness: long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:230-5. Erratum in: J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson AH, Aadalen RJ, Eilers VE, Winter RB. Treatment of congenital hip dislocation and dysplasia with the Pavlik harness. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;155:25-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.POSNA. DDH: A comprehensive Review of the Pathophysiology and Treatment Strategies for All Ages. In: Davids J, editor. Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America One Day Course; 2005. May 12, 2005; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 2005.

- 24.Weinstein SL. Natural history of congenital hip dislocation (CDH) and hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;225:62-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wedge JH, Wasylenko MJ. The natural history of congenital disease of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61:334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwend RM, Pratt WB, Fultz J. Untreated acetabular dysplasia of the hip in the Navajo. A 34 year case series followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;364:108-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalamchi A, MacEwen GD. Avascular necrosis following treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:876-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Severin E. Congenital dislocation of the hip joint: development of the joint after closed reduction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:507-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HT, Kim JI, Yoo CI. Acetabular development after closed reduction of developmental dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint. With special reference to the complication of osteoarthritis. Acta Chir Scand. 1939;83:58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gotoh E, Tsuji M, Matsuno T, Ando M. Acetabular development after reduction in developmental dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;378:174-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albinana J, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, Morcuende J, Meyer MD, Weinstein SL. Acetabular dysplasia after treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Implications for secondary procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:876-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali AM, Angliss R, Fujii G, Smith DM, Benson MK. Reliability of the Severin classification in the assessment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10:293-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tepper S, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with hip osteoarthritis: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-I). Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nevitt MC, Xu L, Zhang Y, Lui LY, Yu W, Lane NE, Qin M, Hochberg MC, Cummings SR, Felson DT. Very low prevalence of hip osteoarthritis among Chinese elderly in Beijing, China, compared with whites in the United States: the Beijing osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooperman DR, Wallensten R, Stulberg SD. Acetabular dysplasia in the adult. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;175:79-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holen KJ, Tegnander A, Bredland T, Johansen OJ, Saether OD, Eik-Nes SH, Terjesen T. Universal or selective screening of the neonatal hip using ultrasound? A prospective, randomised trial of 15,529 newborn infants. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:886-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malvitz TA, Weinstein SL. Closed reduction for congenital dysplasia of the hip. Functional and radiographic results after an average of thirty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1777-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen IH, Kuo KN, Lubicky JP. Prognosticating factors in acetabular development following reduction of developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14:3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan A, Cundy PJ, Foster BK, Keane RJ, Byron-Scott R. Late diagnosis of congenital dislocation of the hip and presence of a screening programme: South Australian population-based study. Lancet. 1999;354:1514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, Sujov P, Wiener F, Berant M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: a new approach to incidence. Pediatrics. 1999;103:93-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marks DS, Clegg J, al-Chalabi AN. Routine ultrasound screening for neonatal hip instability. Can it abolish late-presenting congenital dislocation of the hip? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:534-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coleman SS. Congenital dysplasia of the hip in the Navajo infant. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;56:179-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pavlik A. The functional method of treatment using a harness with stirrups as the primary method of conservative therapy for infants with congenital dislocation of the hip. 1957. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;281:4-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grill F, Bensahel H, Canadell J, Dungl P, Matasovic T, Vizkelety T. The Pavlik harness in the treatment of congenital dislocating hip: report on a multicenter study of the European Paediatric Orthopaedic Society. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramsey PL, Lasser S, MacEwen GD. Congenital dislocation of the hip. Use of the Pavlik harness in the child during the first six months of life. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:1000-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alexiev VA, Harcke HT, Kumar SJ. Residual dysplasia after successful Pavlik harness treatment: early ultrasound predictors. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iwasaki K. Treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip by the Pavlik harness. Mechanism of reduction and usage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:760-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris IE, Dickens R, Menelaus MB. Use of the Pavlik harness for hip displacements. When to abandon treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;281:29-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eidelman M, Katzman A, Freiman S, Peled E, Bialik V. Treatment of true developmental dysplasia of the hip using Pavlik's method. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12:253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tucci JJ, Kumar SJ, Guille JT, Rubbo ER. Late acetabular dysplasia following early successful Pavlik harness treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11:502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalamchi A, MacFarlane R 3rd. The Pavlik harness: results in patients over three months of age. J Pediatr Orthop. 1982;2:3-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riboni G, Bellini A, Serantoni S, Rognoni E, Bisanti L. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:475-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uçar DH, Işiklar ZU, Kandemir U, Tümer Y. Treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip with Pavlik harness: prospective study in Graf type IIc or more severe hips. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:70-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cashman JP, Round J, Taylor G, Clarke NM. The natural history of developmental dysplasia of the hip after early supervised treatment in the Pavlik harness. A prospective, longitudinal follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:418-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Düppe H, Danielsson LG. Screening of neonatal instability and of developmental dislocation of the hip. A survey of 132,601 living newborn infants between 1956 and 1999. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:878-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosendahl K, Toma P. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. The European approach. A review of methods, accuracy and clinical validity. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paton RW, Hossain S, Eccles K. Eight-year prospective targeted ultrasound screening program for instability and at-risk hip joints in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:338-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paton RW, Srinivasan MS, Shah B, Hollis S. Ultrasound screening for hips at risk in developmental dysplasia. Is it worth it? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teanby DN, Paton RW. Ultrasound screening for congenital dislocation of the hip: a limited targeted programme. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Macnicol MF. Results of a 25-year screening programme for neonatal hip instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:1057-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graf R. Hip sonography—how reliable? Sector scanning versus linear scanning? Dynamic versus static examination? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;281:18-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dorn U, Neumann D. Ultrasound for screening developmental dysplasia of the hip: a European perspective. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17:30-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luhmann SJ, Bassett GS, Gordon JE, Schootman M, Schoenecker PL. Reduction of a dislocation of the hip due to developmental dysplasia. Implications for the need for future surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:239-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lindstrom JR, Ponseti IV, Wenger DR. Acetabular development after reduction in congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:112-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tredwell SJ. Neonatal screening for hip joint instability. Its clinical and economic relevance. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;281:63-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poul J, Bajerova J, Sommernitz M, Straka M, Pokorny M, Wong FY. Early diagnosis of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:695-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krikler SJ, Dwyer NS. Comparison of results of two approaches to hip screening in infants. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hadlow V. Neonatal screening for congenital dislocation of the hip. A prospective 21-year survey. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamilton BE, Miniño AM, Martin JA, Kochanek KD, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2005. Pediatrics. 2007;119:345-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hernandez RJ, Cornell RG, Hensinger RN. Ultrasound diagnosis of neonatal congenital dislocation of the hip. A decision analysis assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:539-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. A population-based comparison of ultrasound and clinical findings. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:64-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]