SUMMARY

Phospholipase C (PLC) isozymes are directly activated by heterotrimeric G proteins and Ras-like GTPases to hydrolyze phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate into the second messengers diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Although PLCs play central roles in myriad signaling cascades, the molecular details of their activation remain poorly understood. As described here, the crystal structure of PLC-β2 illustrates occlusion of the active site by a loop separating the two halves of the catalytic TIM barrel. Removal of this insertion constitutively activates PLC-β2 without ablating its capacity to be further stimulated by classical G protein modulators. Similar regulation occurs in other PLC members, and a general mechanism of interfacial activation at membranes is presented that provides a unifying framework for PLC activation by diverse stimuli.

INTRODUCTION

Numerous hormones, growth factors, neurotransmitters, antigens, and other external stimuli activate phospholipase C (PLC) isozymes to hydrolyze phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns[4,5]P2) into the second messengers diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) (Harden and Sondek, 2006). DAG activates both conventional and nonconventional protein kinase C isoforms, and IP3 promotes release of intracellular calcium. These bifurcating processes are essential for a broad range of cellular (e.g., fertilization, division, differentiation, and chemotaxis) and physiological (e.g., platelet shape change and aggregation, muscle contraction, hormone secretion) events. PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels also are affected by PLCs and directly regulate important biological processes. For example, PLC-catalyzed depletion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 directly modulates activities of more than 20 distinct ion channels (Gamper et al., 2004; Horowitz et al., 2005; Kobrinsky et al., 2000; Suh and Hille, 2005; Yue et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2003). Similarly, localized depletion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 by PLC is required for lamellipodia formation and directional membrane protrusion (Mouneimne et al., 2004) as well as for phagocytic cup formation and subsequent vacuole fusion (Scott et al., 2005). Indeed, direct protein/PtdIns(4,5)P2 interactions dictate proper subcellular localization and attendant functions of many signaling components, and many of these processes are modified by local PLC-promoted depletion of PtdIns(4,5)P2.

Humans express 13 PLCs divided into six classes (PLC-β, -γ, -δ, -ε, -η, and -ζ) based on similarity of primary sequence and shared modes of regulation (Harden and Sondek, 2006; Rhee, 2001). Gαq/11 and Gβγ dimers released from heterotrimeric G proteins activated downstream of G protein-coupled receptors directly bind PLC-β isoforms leading to their activation. PLC-η2 also is activated directly by Gβγ (Zhou et al., 2005, 2008). PLC-γ isoforms are activated by phosphorylation by various receptor and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases. Several PLCs are directly activated by Ras-related GTPases: Ras, Rap, and Rho activate PLC-ε, whereas Rac activates PLC-β2, -β3, and -γ2 (Harden and Sondek, 2006; Piechulek et al., 2005). No well-established protein activators for PLC-δ and -ζ isoforms are known, and these PLCs are uniquely sensitive to physiologically relevant concentrations of calcium, which might provide the primary basis for their regulation. Despite these diverse modes of activation, basal activity of all PLCs is low relative to their maximal activation.

Herein we show a common mechanism for autoinhibition of PLCs that in turn provides a means for their activation by diverse signaling inputs. More specifically, the crystal structure of a large fragment of PLC-β2 highlights the occlusion of its active site by a portion of the linker that separates the conserved X and Y boxes comprising the catalytic TIM barrel. Deletion of this linker constitutively activates PLC-β2 in vitro and in cells, but the mutant enzyme retains capacity to be activated by Gαq, Gβγ, and Rac1. Similar deletions in PLC-β1, -δ1, and -ε also result in marked activation of these diversely regulated isozymes. The X/Y linker regions in these PLCs share no sequence conservation. Nonetheless, a preponderance of clustered, negatively charged residues is present in all of these linkers, and we present a unifying model for interfacial activation of PLCs whereby negatively charged membranes sterically and electrostatically repel X/Y linkers within PLCs, leading to open active sites that allow substrate access and accelerated hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2. In this fashion, a common autoinhibitory mechanism provides rigid control over the suite of PLCs that can be harnessed by diverse signaling inputs to impart highly localized and robust PtdIns(4,5)P2 hydrolysis.

RESULTS

Crystal Structure of PLC-β2

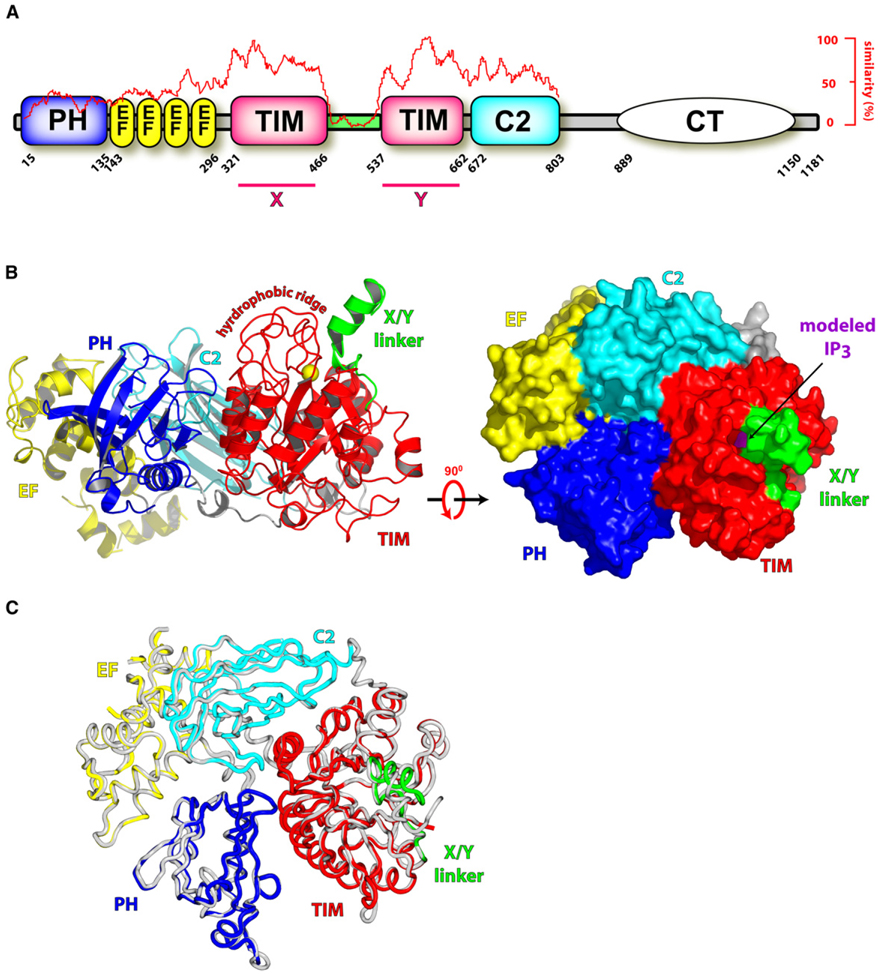

Most PLC isozymes possess a conserved core encompassing an N-terminal pleckstrin homology domain followed by an array of four EF hands, a catalytic TIM barrel, and a flanking C2 domain (Figure 1A). The crystal structure of this fragment was recently determined for PLC-β2 bound in a GTP-dependent fashion to its upstream activator, Rac1 (Jezyk et al., 2006).

Figure 1. Overall Structure of PLC-β2.

(A) PLC-β isozymes are composed of an N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, an array of EF hands, a catalytic TIM barrel split by a highly degenerate linker sequence (green), a C2 domain, and a C-terminal coiled-coil (CT) domain necessary for homodimerization. Sequence conservation of all human PLCs is graphed (red trace) relative to their shared domain architecture, X and Y regions of high sequence conservation are indicated, and absolute domain borders are listed for human PLC-β2.

(B) The X/Y linker occludes the active site of PLC-β2. The 1.6 Å resolution structure of PLC-β2 is depicted in ribbon form (left panel) with domain boundaries colored as in (A) and the approximate membrane-binding surface at the top. Also shown are the calcium cofactor (yellow sphere) within the active site and the hydrophobic ridge that is a major point of contact with membranes. Surface representation of PLC-β2 (right panel) rotated 90° with respect to the left panel emphasizes the occlusion of the active site within the TIM barrel by the X/Y linker. For reference, superposition of the active site of PLC-δ1 containing IP3 and PLC-β2 was used to dock IP3 (purple) into the TIM barrel of PLC-β2.

(C) Superimposition of the crystal structures of the isolated PLC-β2 fragment colored as in (B) and the equivalent fragment from the Rac1-bound form (gray; PDB ID code 2FJU).

To assess potential conformational rearrangements within PLC-β2 necessary for activation by GTP-bound Rac1, we have now determined the high-resolution structure of PLC-β2 in isolation (Figure 1B and see Table S1 available online). Comparison of the holoenzyme and Rac1-bound PLC-β2 revealed no long-range conformational rearrangements within PLC-β2 (Figure 1C). Moreover, the spatial arrangements of active site residues within both structures of PLC-β2 are identical and mimic the constellation of catalytic residues within structures of PLC-δ1 (Figures 2A and 2B). In particular, PLCs require a Ca2+ cofactor, which interacts with the 2-hydroxyl group of the inositol ring of PtdIns(4,5)P2 to promote binding of substrate and stabilization of the transition state. Four polar groups (N312, E341, D343, and E390) ligate the Ca2+ ion in the PLC-δ1 structures (Essen et al., 1996, 1997a), and equivalent functional residues in PLC-β2 (N328, E357, D359, E408) identically position a catalytically required Ca2+ ion. Other residues in PLC-δ1 coordinate the 1-phosphoryl (H311, N312, H356), 4-phosphoryl (K438, S522, R549), and 5-phosphoryl (K440) groups of the PtdIns(4,5)P2 substrate, and equivalent residues (H327, N328, H374, K461, S571, R598; K463) are similarly arranged within the active site of both structures of PLC-β2. In structures of PLC-δ1, Tyr551 makes extensive van der Waals interactions with the inositol ring of the substrate PtdIns(4,5)P2; Tyr600 of PLC-β2 is optimally placed for these interactions. Therefore, the active sites of PLC-β2 and -δ1 are highly similar, and neither gross conformational changes nor more subtle alterations of active site residues are observed in comparison of the independently determined structures of holo-PLC-β2 and its Rac1-bound counterpart.

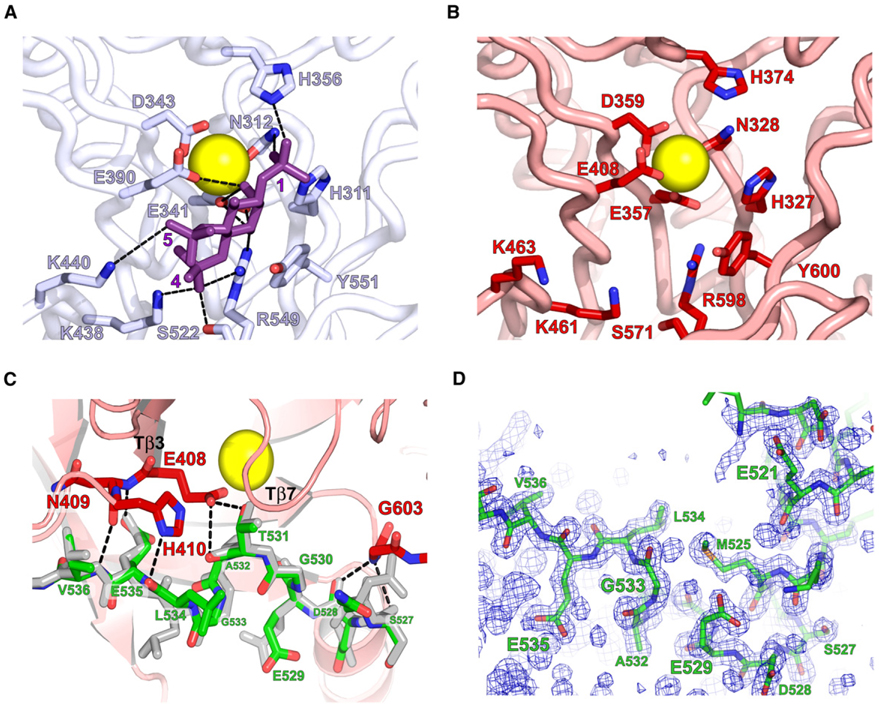

Figure 2. Structural Details of the Active Site of PLC-β2.

(A and B) Active site residues in PLC-δ1 that coordinate calcium (yellow) and interact (dashed lines) with IP3 (purple) are conserved in (B) PLC-β2.

(C) An extended portion of the X/Y linker (green; residues 527–536) participates in a set of H bonds (dashed lines) with active site residues (red) of PLC-β2. The equivalent portion of the linker from the structure of PLC-β2 bound to Rac1 is shown in gray.

(D) Simulated annealing omit map (2Fo – Fc; contoured at 1σ) highlighting the density for residues 517–537 of the X/Y linker.

Inspection of both structures of PLC-β2 reveal that the active site is identically occluded by a portion of the linker connecting the highly conserved X and Y boxes comprising the catalytic TIM barrel (Figure 2C). The X/Y linker of PLC-β2 spans approximately 70 amino acids (466–537), but only 22 of these residues (516–537) are ordered in the structure of isolated PLC-β2. The first half (residues 516–529) of this region forms a short α helix that is roughly perpendicular to the body of the TIM barrel capped at its C terminus by a tight turn and an extended region (residues 530–537) including a small 310 helix (residues 530–534). The C terminus of the α helix and the extended region make extensive contacts with the phospholipase active site. In particular, the turn within the X/Y linker is anchored to the TIM barrel through a bifurcated hydrogen-bonding arrangement composed of the carbonyl oxygens of Ser 527 and Asp 528 of the linker and the amide of Gly 603 within the Y box and between the secondary structure elements, Tβ7 and Tα6 (Essen et al., 1996; Jezyk et al., 2006). At the C-terminal end of the extended portion of the X/Y linker, residues 531–536 participate in a set of five H bonds with residues 408–410 of the TIM barrel located at the end of β strand, Tβ3.

We initially conjectured that occlusion of the active site in the structure of Rac1-bound PLC-β2 arose as an artifact of crystallization conditions (i.e., precipitating reagents or lattice contacts). This idea was encouraged by knowledge that the X/Y linker was disordered and not observed in earlier high-resolution crystal structures of PLC-δ1 lacking its PH domain (Essen et al., 1996, 1997a, 1997b). However, observation that an identical occlusion of the active site occurred in the structure of the isolated form of PLC-β2 generated under dramatically different crystallization conditions led us to hypothesize that the X/Y linker serves to autoinhibit PLC-β2 and that regulated removal of the linker from the active site of PLC-β2 is an obligate step necessary for phospholipase activity. Initial phases used to model the isolated form of PLC-β2 were obtained by molecular replacement using the original PLC-β2 structure. Therefore, to rule out potential model bias and to confirm the accuracy of the isolated PLC-β2 structure within the area of the X/Y linker, this region was deleted from the final coordinates prior to a round of simulated annealing and subsequent calculation of electron density (Figure 2D). The resulting simulated annealing omit map strongly supports the final model for the X/Y linker and indicates that this region is energetically predisposed to occlude the active site of PLC-β2 under differing crystallization conditions.

Deletion of the X/Y Linker Activates PLC-β Isozymes

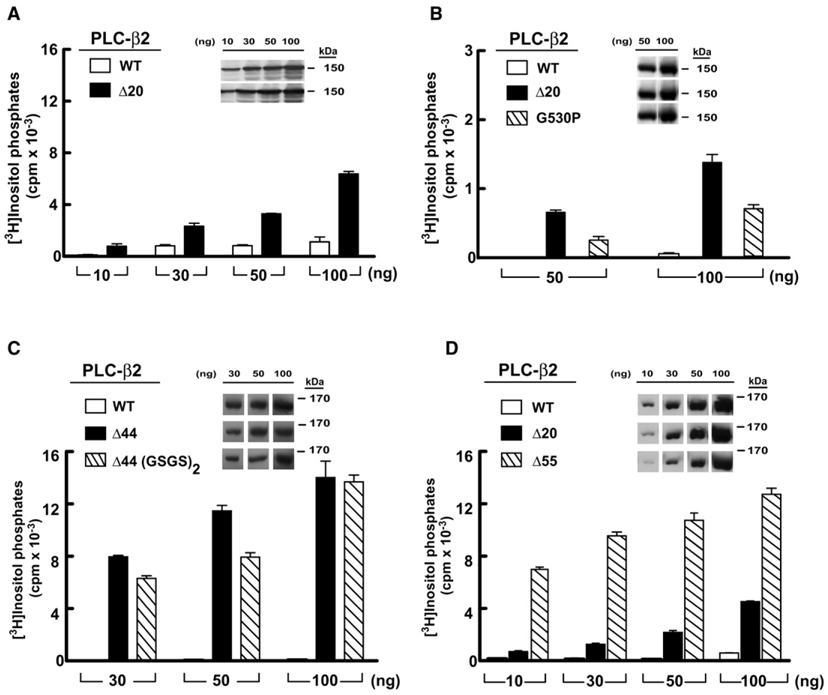

With the goal of determining whether the ordered portion of the X/Y linker is involved in the regulation of catalysis by PLC-β2, we deleted residues 516–535 and compared the phospholipase activity of this mutant isozyme (PLC-β2Δ20) to that of wild-type PLC-β2 after expression in COS-7 cells (Figure 3A). [3H]Inositol phosphate accumulation was quantified (Supplemental Experimental Procedures) in cells transfected with a broad range of DNA concentrations. The phospholipase activity of PLC-β2Δ20 was markedly (5- to 20-fold) elevated relative to wild-type PLC-β2 at all amounts of transfected DNA. Similar amounts of protein expression were observed for both forms of PLC-β2 at all transfected DNA concentrations (Figure 3, inset). To probe further the requirement for specific interactions between the X/ Y linker of PLC-β2 and its active site, Gly 530 was mutated to proline. This substitution disfavors formation of the 310 helix within the extended portion of the X/Y linker and likely disrupts specific interactions between the X/Y linker and the catalytic TIM barrel of PLC-β2. Consistent with these expectations, PLC-β2(G530P) exhibited basal activity that also was markedly elevated relative to wild-type PLC-β2 (Figure 3B), although this enhancement was approximately half the phospholipase activity of PLC-β2Δ20. Mutation of the adjacent threonine residue to alanine also resulted in a mutant isozyme (PLC-β2[T531A]) that exhibited markedly elevated basal activity (data not shown).

Figure 3. Deletion of the X/Y Linker Constitutively Activates PLC-β2.

COS-7 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of DNA encoding either wild-type (white bars) or the indicated mutant forms of PLC-β2 (black or hatched bars).

(A) PLC-β2Δ20 lacking the ordered part of the X/Y linker.

(B) PLC-β2 harboring a G530P substitution within the X/Y linker.

(C) PLC-β2Δ44 lacking the majority of the disordered portion of the linker.

(D) PLC-β2Δ55 lacking the linker with the exception of residues that occupy the active site. [3H]Inositol phosphate accumulation in cells transfected with vector alone was subtracted from all measurements. Data shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate samples and are representative of data obtained in three or more experiments. Insets confirm equivalent expression of PLC-β isozymes by western blotting of COS-7 cell lysate.

The data presented above are consistent with the conclusion that the ordered region of the X/Y linker of PLC-β2 is auto-inhibitory. However, the majority of the X/Y linker in PLC-β2 is disordered, and this region was also assessed for autoinhibitory capacity. Strikingly, deletion of residues 470–515 (PLC-β2Δ44), which includes the majority of the disordered region of the X/Y linker, results in an isoform that has approximately 10-fold higher basal activity relative to PLC-β2Δ20 (Figures 3C and Figure 7A). A similar increase in basal activity relative to PLC-β2Δ20 was observed when residues 470–524 were deleted (PLC-β2Δ55), which removes the linker with the exception of residues that occupy the active site (Figures 3D and Figure 7A). No appreciable effect on the basal activity of PLC-β2Δ44 occurred upon addition of four extra residues (i.e., Gly-Ser-Gly-Ser), strongly suggesting that deletion of the disordered region does not intrinsically affect the flanking structured regions (Figure 3C).

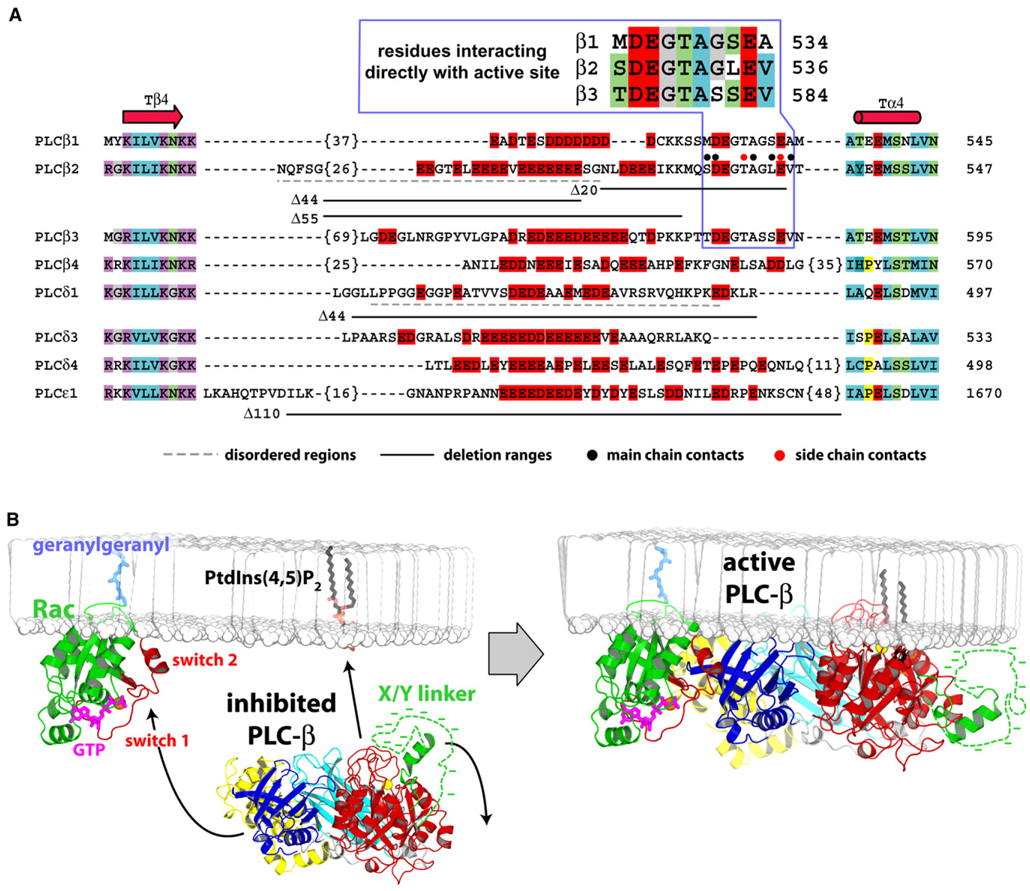

Figure 7. Sequence Details of the X/Y Linker within PLC Isozymes and Model for Interfacial Activation of PLC-β2.

(A) The majority of human PLCs possess a region of dense negative charge (red boxes) within their X/Y linkers. Otherwise, these insertions are highly variable in length, possess no significant sequence conservation, and form loops between highly conserved secondary structure elements (Tβ4, Tα4) of the TIM barrel. Number of residues not listed are in brackets; disordered regions within the crystal structures of PLC-δ1 and PLC-β2 are underlined with dashed lines (gray); and regions deleted for biochemical analyses are underlined (solid black). Also highlighted are residues within the X/Y linker of PLC-β2 that participate in direct main-chain (black circles) and side-chain (red circles) H-bonds with the TIM barrel. This region is expanded above the alignment for the PLC-β isozymes.

(B) Basally inactive PLC-β2 is cytosolic and inhibited by occlusion of its active site by the ordered portion (green) and the disordered portion (dotted green line with associated negative charge represented by dashes) of the X/Y linker (left panel). Membrane-resident GTP-bound Rac (green with switch regions red) recruits and orients PLC-β2 at membranes through interaction of the switch regions with the PH domain (blue) of PLC-β2. Upon engagement of PLC-β2 by Rac, the X/Y linker region is repelled from negatively charged membranes, which frees the active site to extract partially a molecule of PtdIns(4,5)P2 from the membrane in preparation for its hydrolysis into IP3 and DAG. X/Y linkers within other PLCs are envisioned to behave similarly. Arrows indicate movement of PLC-β2 and the X/Y linker.

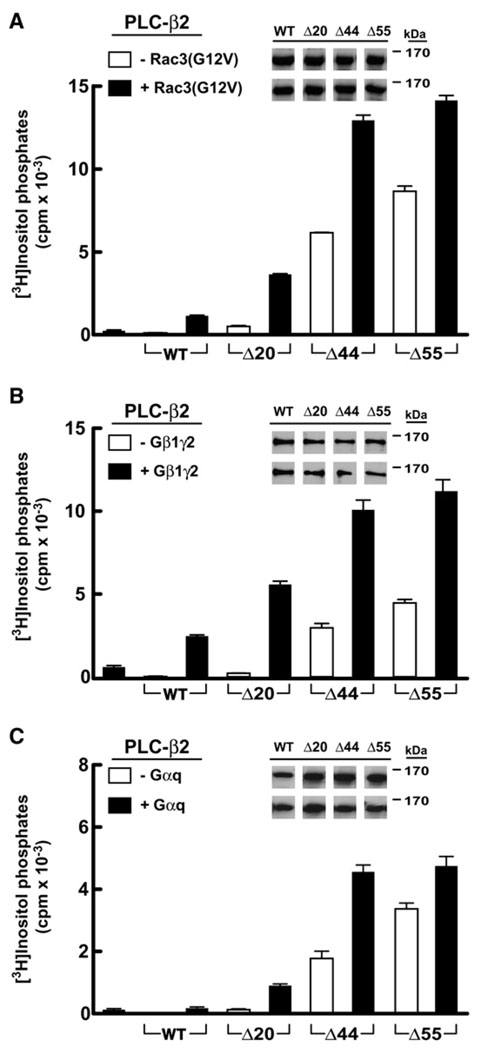

PLC-β2 is directly activated by Rac GTPases as well as heterotrimeric G proteins, and the capacity of these modulators to enhance the phospholipase activity of the linker-deleted forms of PLC-β2 also was tested after coexpression in COS-7 cells (Figure 4 and Figure S1). As expected, cotransfection of plasmids encoding wild-type PLC-β2 and constitutively active Rac3 (Rac3[G12V]) resulted in a substantial increase in [3H]inositol phosphate accumulation relative to transfection of either plasmid alone (Figure 4A). Furthermore, cotransfection of the mutant forms of PLC-β2 with Rac3(G12V) resulted in levels of [3H]inositol phosphate accumulation that consistently were 2- to 7-fold higher than those observed with wild-type PLC-β2. Gβγ dimers and GTP-bound Gα subunits of the Gq/11 family also directly bind PLC-β isozymes to enhance phospholipase activity, and cotransfection of either Gβ1γ2 (Figure 4B) or Gαq (Figure 4C and Figure S1) with the linker-deleted forms of PLC-β2 produced results similar to those observed for Rac3(G12V). Gβ1γ2 coexpression with PLC-β2 mutants increased [3H]inositol phosphate production 2- to 5-fold compared to wild-type PLC-β2, and Gαq coexpression reproducibly led to 2- to 7-fold increases. Thus, deletion of the X/Y linker does not prevent the capacity of Rac3, Gβ1γ2, or Gαq to stimulate the phospholipase activity of PLC-β2.

Figure 4. Activation of PLC-β2 by G Protein Activators Is Retained in PLC-β2 Lacking the Majority of the X/Y Linker.

COS-7 cells were transfected with DNA encoding either PLC-β2 or the indicated PLC-β2 deletion forms in the presence or absence of 30 ng of constitutively active Rac3(G12V) (A), 150 ng of each subunit of Gβ1γ2 (B), or 100 ng of Gαq (C) prior to quantification of [3H]inositol phosphates and vector subtraction. All transfections used 30 ng of each PLC form except for (C), where 10 ng of each PLC was transfected. Endogenous activity resulting from transfection of either G protein or Rac3(G12V) alone is indicated by the first bar on each plot. Data are the mean ± SD of triplicate samples and are representative of results from three or more experiments. PLC-β2 expression was assessed by western blotting (insets).

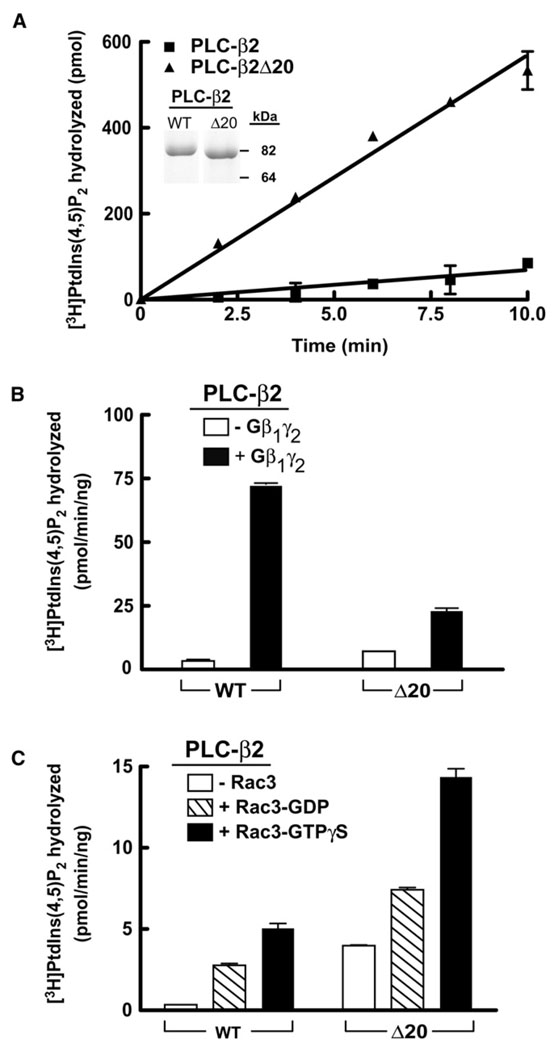

With the goals of confirming and extending the observations made in studies of phospholipase C activity after overexpression in COS-7 cells, we deleted residues 516–535 of the X/Y linker from the truncated form of PLC-β2 used for crystallization and purified this truncated PLC-β2Δ20 to homogeneity after baculoviral-mediated expression in insect cells. Purity of truncated PLC-β2Δ20 was compared to its undeleted counterpart by SDS-PAGE (Figure 5A, inset). The specific activity of purified, truncated PLC-β2 for hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 presented as substrate in mixed detergent phospholipid micelles was ~1.4 µmol/min/mg (Figure 5A), which is similar to previously published activities observed with full-length PLC-β2 and other PLC isozymes using similar conditions (Morris et al., 1990; Seifert et al., 2004; Waldo et al., 1996). In contrast, and consistent with the cellular measurements of phospholipase activities, the activity (~12 µmol/min/mg) of truncated PLC-β2Δ20 under identical assay conditions was approximately 8-fold higher than that observed with wild-type PLC-β2.

Figure 5. Purified PLC-β2 Lacking the Ordered Region of the X/Y Linker Is Constitutively Active and Is Further Stimulated by Gβ1γ2 and Rac1 upon Reconstitution in Lipid Vesicles.

(A) Purified PLC-β2 (5 ng) or PLC-β2Δ20 (5 ng) was incubated with mixed detergent- lipid vesicles containing [3H]PtdIns(4,5)P2 for the indicated times at 30°C. Purity of proteins (2 µg, inset) was assessed by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Hydrolysis of [3H]PtdIns(4,5)P2 was quantified in phospholipid vesicles reconstituted with (B) purified Gβ1γ2 (250 nM, final concentration) or (C) purified Rac1 (300 nM, final concentration) preincubated with 10 µM GDP or GTPγS for 30 min. [3H]PtdIns(4,5)P2 hydrolysis was initiated by addition of either 1 ng or 5 ng PLC-β2 or PLC-β2Δ20, and incubations were terminated after 10 min at 30°C. The data are the mean ± range of duplicate determinations, and the results are representative of three individual experiments.

The capacity of Gβγ and Rac to activate these two truncated forms of PLC-β2 also was studied in phospholipid vesicles using techniques previously described (Boyer et al., 1992; Seifert et al., 2004; Waldo et al., 1991). Reconstitution of Gβ1γ2 resulted in elevated stimulation of phospholipase C activity for both forms of PLC-β2 (Figure 5B). However, the fold activation of the wild-type fragment of PLC-β2 was higher than that of PLC-β2Δ20, due to the increased basal activity of PLC-β2Δ20. In similar studies using purified and prenylated Rac1, increases in phospholipase activity also were observed for both forms of PLC-β2 (Figure 5C). Enhanced phospholipase activity was dependent on the nucleotide-bound state of Rac1 with at least 2-fold higher enzyme activities observed in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable analog of GTP, GTPγS. The fold stimulation over basal enzyme activity observed with GTPγS-loaded Rac1 was higher with wild-type PLC-β2, but the magnitude of the increase was much larger with PLC-β2Δ20, which, as illustrated in Figure 5A, exhibits up to 10-fold higher basal activity in the absence of G protein regulators.

Constitutive Activation of Diverse PLC Isozymes

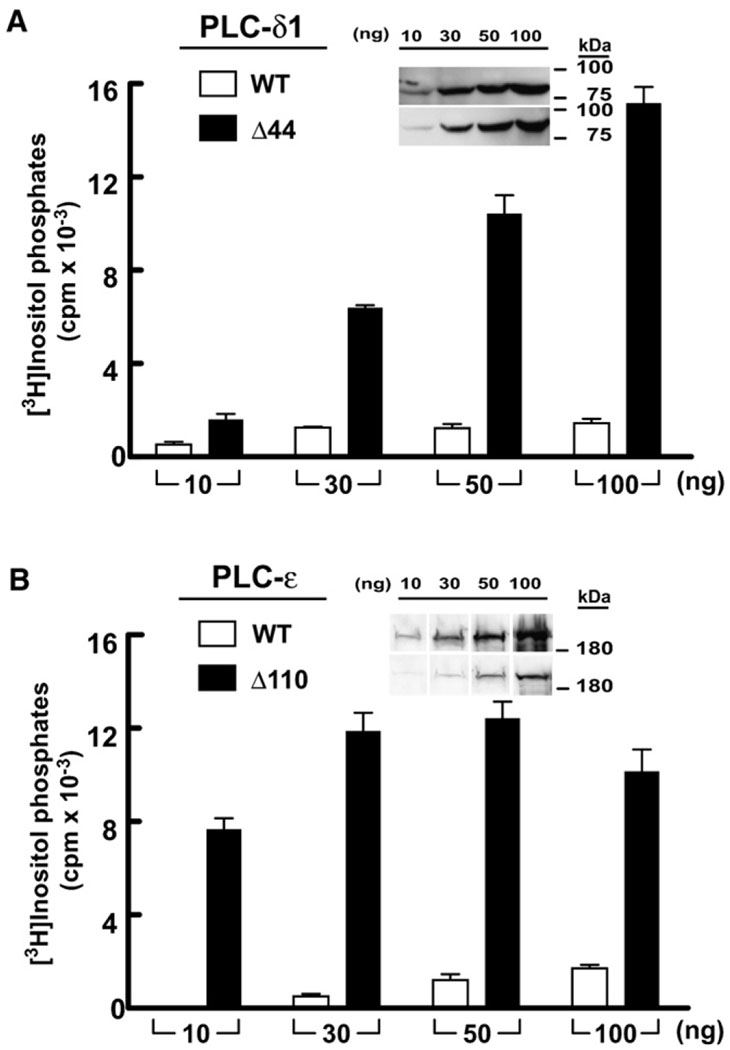

We hypothesized that the equivalent region between the X and Y boxes of the catalytic TIM barrel plays a similar role in regulation of the activity of other PLC isoforms, and therefore deletion studies were carried out with other PLC isozymes. Exclusive of the X/Y linker, PLC-β1 and PLC-β2 are highly conserved isozymes, and deletion of the X/Y linker of PLC-β1 equivalent to the ordered portion of PLC-β2 resulted in enhanced phospholipase activity of PLC-β1 both in cells and in vitro (data not shown). More interestingly, PLC-δ1, which is evolutionarily divergent relative to PLC-β1 and -β2 is also autoinhibited by its X/Y linker (Figure 6A). In this case, deletion of the 44 amino acids that comprise the X/Y linker in PLC-δ1 resulted in up to a 10-fold increase in phospholipase C activity compared to wild-type PLC-δ1 in transfection experiments. This remarkable activation of PLC-δ1 occurs despite the fact that the X/Y linker could not be modeled in several crystal structures of this PLC isozyme, indicating that it is disordered (Essen et al., 1996, 1997a, 1997b). Given the results obtained with PLC-β isozymes and PLC-δ1, we also examined the role of the X/Y linker (~110 residues) found in PLC-ε. Expression of PLC-ε lacking its X/Y linker in COS-7 cells revealed an increase in phospholipase activity of at least 20-fold relative to wild-type PLC-ε (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Deletion of the X/Y Linker Constitutively Activates Diverse PLC Isozymes.

COS-7 cells were transfected with PLC-δ1 (A) or PLC-ε (B) in tandem with the respective forms of these isozymes lacking the X/Y linker. In all cases, accumulation of inositol phosphates in cells transfected with vector alone was subtracted. Data are the mean ± SD for triplicate samples, and the results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Western blotting (insets) confirms expression of PLC isozymes in COS-7 cell lysate.

DISCUSSION

Various PLCs Are Inhibited by Their X/Y Linkers

In order to understand how G proteins modulate PLCs, we determined the crystal structure of a large fragment of PLC-β2 in isolation and compared it with the previously determined crystal structure of PLC-β2 bound to Rac1 (Figure 1 and Figure 2). This comparison revealed that the structure of PLC-β2 is not altered upon binding Rac1. On the contrary, the two forms of PLC-β2 are highly similar, and this similarity extends to the active site, which is identically occluded by a portion of the X/Y linker. This occlusion is incompatible with phospholipase activity of PLC-β2, since essentially the entire active site is occupied by residues 527–536 of the X/Y linker. Our structural assessment was confirmed biochemically, since deletion of the ordered region of the X/Y linker from PLC-β2 activated the enzyme as evidenced by 5- to 20-fold increases in both inositol phosphate accumulation in COS-7 cells (Figure 3) and rates of hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 observed in reconstituted vesicles using purified proteins (Figure 5A). Indeed, the structural basis for the autoinhibition of PLC-β2 is dramatically highlighted by the fact that single substitutions within the ordered portion of the X/Y linker that occupies the active site, e.g., G530P, markedly increase the basal phospholipase activity of PLC-β2 (Figure 3B). To the best of our knowledge, the activation of a PLC caused by a single substitution of the X/Y linker has not previously been reported.

Despite increased basal phospholipase activity, PLC-β2 forms lacking portions of the X/Y linker maintain regulation by heterotrimeric G proteins and Rac in both cells and reconstitution assays using purified components (Figure 4 and Figure 5 and Figure S1). For both sets of experiments, fold enhancements were lower for deleted forms of PLC-β2 relative to wild-type PLC-β2. This situation might reflect the tight basal control of wild-type PLC-β2 relative to mutated, constitutively active forms of this enzyme.

Major sites of interactions with PLC-β isozymes have been mapped for Gβγ dimers, Gαq, and Rac1. For instance, detailed biochemical (Illenberger et al., 2003a, 2003b; Snyder et al., 2003) and structural analyses (Jezyk et al., 2006) indicate that the Rac isozymes solely engage the PH domain of PLC-β isozymes. As shown here, no conformational changes are propagated from the site of Rac engagement, and Rac GTPases must promote phospholipase activity of PLC-βs by enhancing their localization and optimizing their orientation at substrate membranes. Therefore, deletion of the X/Y linker within PLC-β2 would not be expected to prevent Rac engagement and stimulation of PLC-β2, which is consistent with the results described here. This view is further supported by the fact that micromolar concentrations of soluble Rac1-GTPγS failed to enhance the phospholipase activity of full-length, wild-type PLC-β2 operating on cholate-solubilized PtdIns(4,5)P2 (Figure S2). Under these conditions, Rac1-GTPγS would be expected to activate PLC-β2 only via an allosteric mechanism. In contrast, Gβγ dimers have been shown to interact with PLC-βs not only through the PH domain but also through adjacent portions of the EF hands and regions within the TIM barrel (Barr et al., 2000; Wang et al., 1999b, 2000). While these studies have not specifically implicated the X/Y linker of PLC-βs as directly interacting with Gβγ dimers, the mapped interaction interface is expansive and adjacent to the X/Y linker in the structure of PLC-β2. Therefore, Gβγ dimers might interact with parts of the X/Y linker to fully modulate PLC-βs. Nevertheless, no portion of the X/Y linker is absolutely required for the activation of PLC-β2 by Gβ1γ2 (Figure 4B). Gαq has been proposed to interact with the unique C-terminal homodimerization domain (Blank et al., 1993; Kim et al., 1996; Park et al., 1993; Wu et al., 1993) and possibly the C2 domain (Wang et al., 1999a). However, Gαq has not been implicated in binding to the X/Y linker of PLC-β isozymes, which is consistent with the fact that PLC-β2 forms lacking the X/Y linker retain robust activation by Gαq in cotransfection experiments (Figure 4C and Figure S1).

The portion of the X/Y linker region of PLC-β2 that occludes its active site is conserved in PLC-β1 and -β3, suggesting that these PLCs are similarly autoinhibited. Indeed, deletion of the X/Y linker within PLC-β1 also increased basal phospholipase activity (data not shown). More significantly, deletions of the X/Y linkers within PLC-δ1 and -ε also lead to constitutively active PLCs (Figure 6).

Diverse Linkers but One Regulatory Mechanism

The X/Y linker regions within PLCs clearly engender major autoinhibition of several, and possibly all, PLC isozymes. How does this occur?

X/Y linkers of PLC isoforms vary greatly in both length and sequence (Figure 7A), and even within subgroups of PLCs, no significant conserved regions exist within the sequences that separate the TIM barrels. However, an unusually high density of negatively charged residues provides at least one distinguishing characteristic of the X/Y linker in the majority of PLC isoforms. We conclude that these highly negatively charged X/Y linkers provide important control of PLC activities at negatively charged substrate membranes, and we have formulated a model of interfacial activation of PLCs (Figure 7B). The central tenet of this model is that the negatively charged X/Y linkers are sterically and electrostatically repelled from phospholipid membranes upon recruitment and orientation of PLCs at these PtdIns(4,5)P2-containing surfaces. The X/Y linkers provide a general mode of occlusion of the active site of PLCs that is dependent on the overall length and negative charge of the linker region. Thus, the active sites of PLC isoforms are effectively shielded, and spurious, unregulated hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 is prevented. This model is consistent with the extremely high basal activities of PLC-β2Δ44 and PLC-β2Δ55, which lack the majority of the X/Y linker yet retain the portion of the X/Y linker that directly interacts with the active site. In comparison, substitution or deletion of the ordered portion of the X/Y linker of PLC-β2 is only partially activating. Therefore, for PLC-β2, and presumably the other PLC-β isozymes, the ordered region of the X/Y linker appears to fine-tune access to the active site while the negatively charged and disordered region serves as the major autoinhibitory determinant.

This model also explains several disparate observations in the literature whereby manipulation of X/Y linkers affects the phospholipase activity of PLCs. For instance, protease cleavage of PLC-δ1 (Ellis et al., 1993), -β2 (Schnabel and Camps, 1998), or -γ1 (Fernald et al., 1994) within the X/Y linker results in a concomitant increase in phospholipase activity. In a different vein, active PLC-γ1 (Horstman et al., 1996) and -β2 (Zhang and Neer, 2001) can be reassembled by coexpression of the N- and C-terminal halves of these isozymes. Coexpression of these fragments lacking portions of the X/Y linker resulted in PLCs with high basal phospholipase activity. Similarly, mutational deletion of the X/Y linker of PLC-γ1 (Horstman et al., 1999) elevates its phospholipase activity. Finally, PLC-δ1 (Sidhu et al., 2005) and -γ1 (Horstman et al., 1999) are inhibited by portions of their X/Y linkers supplied in trans. All of these examples point to a conserved autoinhibitory role for the X/Y linker of PLC isozymes.

Several important ramifications arise from this general model of interfacial activation of PLC. Foremost on this list is that any mechanism that steers the active site of a PLC isozyme toward phospholipid membranes should force the negatively charged X/Y linker away from the active site, therein relieving autoinhibition of the enzyme. Our structures of PLC-β2 with and without bound Rac1, together with measurements of enzyme activity, illustrate that this idea fully explains the capacity of Rac GTPases to activate PLC-β2. Our mutational data also indicate that this mechanism almost certainly applies to activation of PLC-β isozymes by Gβγ and Gαq/11. Consistent with this assumption, major binding sites for these modulators do not include the active site or X/Y linker of PLC-β isoforms.

The crystal structure of Rac1 bound to PLC-β2 (Jezyk et al., 2006) indicates that Rac isozymes engage solely the PH domain of PLC-β2, which is distant from the active site. Comparison with the crystal structure of the unbound form of PLC-β2 presented here (Figure 1 and Figure 2), as well as the included experimental data (Figure 4 and Figure 5 and Figure S2), indicates that no conformational changes propagate into the active site as a consequence of Rac binding. Therefore, Rac GTPases must activate PLC-β2 by localizing and orienting the phospholipase at substrate membranes. Since the X/Y linker of PLC-β2 is autoinhibitory and our data suggest that Rac does not modify this region, it seems incontrovertible that the X/Y linker is removed from the active site of PLC-β2 by a secondary means, namely steric and electrostatic repulsion from negatively charged membranes.

It is unclear if PLC-δ isozymes are modulated by direct interactions with regulatory proteins. However, the PH and C2 domains of these isozymes form anchor points with phospholipid membranes through their interaction with PtdIns(4,5)P2 (Ferguson et al., 1995; Garcia et al., 1995) and Ca2+ (Essen et al., 1997b), respectively. Elevated concentrations of intracellular calcium or PtdIns(4,5)P2 over basal levels result in the association of PLC-δ isozymes with membranes, and thus these PLC isoforms are subject to interfacial activation. Deletion of the X/Y linker of PLC-δ1 is markedly activating despite several crystal structures of PLC-δ1 (Essen et al., 1996, 1997a, 1997b) that indicate the entire X/Y linker is disordered. We conclude that this relatively short, negatively charged X/Y linker occupies a volume immediately over the active site consisting of numerous conformations. Thus, the disordered X/Y linker is capable of autoinhibition by hindering productive binding of PLC-δ1 to membranes (Figure S3) and thereby restricting access of PtdIns(4,5)P2 to the active site. Only upon increased intracellular Ca2+ and subsequent anchorage of PLC-δ1 to membranes would the X/Y linker region, now repelled by the negative electrostatic potential of the membranes, vacate this volume to allow unfettered access to substrate.

A minority of PLCs do not possess highly negatively charged and disordered X/Y linker regions. For example, PLC-γ isozymes contain X/Y linkers with well-formed domains—a split PH domain, two SH2 domains, and an SH3 domain—and are activated by tyrosine phosphorylation within the X/Y linker (Ozdener et al., 2002; Rodriguez et al., 2001; Sekiya et al., 2004). The X/Y linkers of human PLC-η1 and -η2 are not highly negative overall but do possess dense clusters of negatively charged residues near their ends. PLC-ζ expression is restricted to sperm and is required for the propagation of calcium oscillations needed for cell division after fertilization (Saunders et al., 2002; Swann et al., 2006). The two major human PLC-ζ isoforms have dramatically divergent X/Y linkers. One form (NCBI accession number EAW96389) contains a highly negatively charged X/Y linker spanning approximately 85 residues. The other form (NP_149114) has an X/Y linker that is half the size and highly basic. It remains to be understood how these two X/Y linkers regulate PLCs. Indeed, Nomikos and coworkers (Nomikos et al., 2007) recently reported that the dense positive region in the X/Y linker of PLC-ζ is important for membrane association and activity.

PLC isozymes are highly efficient lipases capable of turning over the entire pool of available PtdIns(4,5)P2 within seconds of their regulated activation. Without effective inhibition of the phospholipase activities of PLCs, cellular PtdIns(4,5)P2 pools would be in enormous dynamic flux, and the capacity of cells to modulate this flux as a means of information relay through various signal transduction cascades would be highly compromised. X/Y linkers inserted into the catalytic cores of PLC isozymes serve a common autoinhibitory function that tightly couples phospholipase activation with the proximity of PLCs to their substrate membranes. This common form of autoinhibition can be overcome by a wide variety of signaling inputs that allow PLCs to integrate diverse signaling cascades critical for a multitude of cellular and physiological functions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Crystallization and Structure Determination of PLC-β2

A fragment of human PLC-β2 (residues 1–799) lacking the unique C-terminal homodimerization domain was crystallized in sitting drops (1 µl PLC-β2 at 15 mg/ml and 1 µl reservoir) at 18°C using vapor diffusion against a reservoir containing 16% (v/v) isopropanol, 2% (v/v) dioxane, 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 100 mM Tris (pH 8). Crystals grew in ~6 days and were cryoprotected by direct addition of 10 µl of 20% glycerol to sitting drops for 5–20 min before freezing in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at the Argonne National Laboratory on the SER-CAT beamline 22-ID. Data were indexed and processed by using HKL2000. The coordinates of PLCβ2 bound to Rac-GTPγS were used as a search model for molecular replacement using the program PHASER (McCoy et al., 2005) within the CCP4 suite of programs (CCP4, 1994). Model building was carried out using O (Jones et al., 1991), version 6.2.2, and refinement was performed using CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) and Refmac (Murshudov et al., 1997).

Construction of Deletions within PLC-β2, PLC-δ1, and PLC-ε

Standard PCR-mediated mutagenesis (Stratagene; QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Manual) was used to introduce deletions into the X/Y linkers of full-length PLC-β2, -δ1, and -ε in pcDNA3.1. Mutagenic primers included 12 base pairs encoding a Gly-Ser-Gly-Ser insertion spanning the deleted regions (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

The truncated form of PLC-β2 used for crystallization was also mutated identically in pFastBac for studies using purified protein. All mutant genes were verified by automated DNA sequencing of the entire open reading frame.

Transfection of COS-7 Cells with PLC-β2, PLC-δ1, and PLC-ε

The accumulation of [3H]inositol phosphates was measured in transiently transfected COS-7 cells as previously described (Wing et al., 2003). See also the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Expression and Purification of Truncated Forms of PLC-β2

pFastBacHT C vectors encoding either PLC-β2 or PLC-β2Δ20 (both lacking the unique C-terminal domain; residues 800–1181) were transformed into DH10Bac cells (Invitrogen) to produce bacmid DNA, which was subsequently used to generate baculovirus in Sf9 cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen Bac-to-Bac Manual). High Five cells at a cell density of 1.5 × 106 were infected with baculovirus encoding individual PLC-β2 constructs at an MOI of approximately 1.0 for 48 hr at 27°C.

Cells were harvested at 3000 rpm and resuspended in buffer containing 10 mM imidazole, 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 400 mM NaCl. Cell suspensions were lysed using an Emulsiflex C5 homogenizer (Avestin) and spun at 60,000 rpm for 45 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were applied to a 5 ml HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) charged with Ni2+, washed with 10 column volumes (CV) of buffer A (10 mM imidazole, 20 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 10% [v/v] glycerol, and 400 mM NaCl) and 5 CV of 5% buffer B (buffer A containing 1 M imidazole), and PLC-β2 forms were eluted with a step gradient of 40% buffer B. Eluted PLC-β2 forms were dialyzed overnight in S1 buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 5% [v/v] glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT) in the presence of the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease to allowcleavage of the His tag. Proteins were subsequently applied to a SOURCE 15Q anion exchange column (GE Healthcare) and eluted in a linear gradient of 0%–40% buffer S2 (S1 + 1 M NaCl) over 10 CV. Fractions containing either purified PLC-β2 or PLC-β2Δ20 were pooled and concentrated using a 50,000 MWCO Vivaspin 20 centrifugal filtering device (Vivascience) and stored at −80°C after flash freezing in liquid nitrogen.

In Vitro Reconstitution Assays to Measure [3H]PtdIns(4,5)P2 Hydrolysis

Phospholipase activity was measured as we have described in detail (Morris et al., 1990; Seifert et al., 2004). Briefly, 50 µM (final concentration/assay) PtdIns(4,5)P2 (Avanti Polar Lipids), and ~4500 cpm of [3H]PtdIns(4,5)P2 (amount/assay) were mixed, dried under a stream of nitrogen, and resuspended in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). Final assay conditions were 50 µM PtdIns(4,5)P2, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 120 mM KCl, 2 mM EGTA, 5.8 mM MgSO4, 0.5% cholate, 0.16 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (FAF-BSA), and 100 µM free Ca2+ in a final volume of 60 µl. [3H]-labeled PtdIns(4,5)P2 was purchased from Perkin-Elmer. Assays were initiated by addition of 5 ng of purified PLC and incubated for various times as indicated in the figure legends. Reactions were stopped by addition of 200 µl of 10% (v/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and 100 µl of 10 mg/ml BSA to precipitate uncleaved lipids and protein. Centrifugation of the reaction mixture isolated soluble [3H]Ins(1,4,5)P3, which was quantified using liquid scintillation counting.

To measure activation of truncated forms of PLC-β2 by purified Rac1 and Gβ1γ2, assays were performed using PE- and PtdIns(4,5)P2-containing phospholipid vesicles as previously described (Boyer et al., 1992; Seifert et al., 2004). See also the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

The Supplemental Data include Supplemental Experimental Procedures, three figures, and one table and can be found with this article online at http://www.molecule.org/cgi/content/full/31/3/383/DC1/.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-GM57391 (J.S. and T.K.H.) and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NSRA) fellowship F32GM074411 (S.N.H.). The authors are indebted to Rhonda Carter and Savitri Maddileti for their outstanding technical assistance and to Alex Singer, Laurie Betts, Jason Snyder, Matthew Cheever, and Gary Waldo for many helpful discussions.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The PLC-β2 sequence has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under ID code 2ZKM.

REFERENCES

- Barr AJ, Ali H, Haribabu B, Snyderman R, Smrcka AV. Identification of a region at the N-terminus of phospholipase C-β3 that interacts with G protein βγ subunits. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1800–1806. doi: 10.1021/bi992021f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank JL, Shaw K, Ross AH, Exton JH. Purification of a 110-kDa phosphoinositide phospholipase C that is activated by G-protein βγsubunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:25184–25191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JL, Waldo GL, Harden TK. βγ-subunit activation of G-protein- regulated phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:25451–25456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (CCP4) Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta. Cryst. D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MV, Carne A, Katan M. Structural requirements of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C-δ1 for enzyme activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;213:339–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essen L, Perisic O, Cheung R, Katan M, Williams RL. Crystal structure of a mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-δ. Nature. 1996;380:595–602. doi: 10.1038/380595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essen LO, Perisic O, Katan M, Wu YQ, Roberts MF, Williams RL. Structural mapping of the catalytic mechanism for a mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Biochemistry. 1997a;36:1704–1718. doi: 10.1021/bi962512p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essen LO, Perisic O, Lynch DE, Katan M, Williams RL. A ternary metal binding site in the C2 domain of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-δ1. Biochemistry. 1997b;36:2753–2762. doi: 10.1021/bi962466t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Sigler PB. Structure of the high affinity complex of inositol trisphosphate with a phospholipase C pleckstrin homology domain. Cell. 1995;83:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald AW, Jones GA, Carpenter G. Limited proteolysis of phospholipase C-γ1 indicates stable association of X and Y domains with enhanced catalytic activity. Biochem. J. 1994;302:503–509. doi: 10.1042/bj3020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Reznikov V, Yamada Y, Yang J, Shapiro MS. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate signals underlie receptor-specific Gq/11-mediated modulation of N-type Ca2+ channels. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10980–10992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3869-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia P, Gupta R, Shah S, Morris AJ, Rudge SA, Scarlata S, Petrova V, McLaughlin S, Rebecchi MJ. The pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-δ1 binds with high affinity to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in bilayer membranes. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16228–16234. doi: 10.1021/bi00049a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden TK, Sondek J. Regulation of phospholipase C isozymes by Ras superfamily GTPases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006;46:355–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Suh BC, Hilgemann DW, Mackie K, Hille B. Phospholipase C in living cells: activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;126:243–262. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstman DA, Destefano K, Carpenter G. Enhanced phospholipase C-γ1 activity produced by association of independently expressed X and Y domain polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7518–7521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstman DA, Chattopadhyay A, Carpenter G. The influence of deletion mutations on phospholipase C-γ1 activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;361:149–155. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illenberger D, Walliser C, Nurnberg B, Diaz Lorente M, Gierschik P. Specificity and structural requirements of phospholipase C-β stimulation by Rho GTPases versus G protein βγ dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2003a;278:3006–3014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illenberger D, Walliser C, Strobel J, Gutman O, Niv H, Gaidzik V, Kloog Y, Gierschik P, Henis YI. Rac2 regulation of phospholipase C-β2 activity and mode of membrane interactions in intact cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003b;278:8645–8652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezyk MR, Snyder JT, Gershberg S, Worthylake DK, Harden TK, Sondek J. Crystal structure of Rac1 bound to its effector phospholipase C-β2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:1135–1140. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CG, Park D, Rhee SG. The role of carboxyl terminal basic amino acids in Gqα dependent activation, particulate association, and nuclear localization of phospholipase Cβ1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:21187–21192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrinsky E, Mirshahi T, Zhang H, Jin T, Logothetis DE. Receptor-mediated hydrolysis of plasma membrane messenger PIP2 leads to K+-current desensitization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:507–514. doi: 10.1038/35019544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AJ, Waldo GL, Downes CP, Harden TK. A receptor and G-protein-regulated polyphosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C from turkey erythrocytes. I. Purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:13501–13507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouneimne G, Soon L, DesMarais V, Sidani M, Song X, Yip SC, Ghosh M, Eddy R, Backer JM, Condeelis J. Phospholipase C and cofilin are required for carcinoma cell directionality in response to EGF stimulation. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166:697–708. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macro-molecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Mulgrew-Nesbitt A, Pallavi P, Mihalyne G, Zaitseva I, Swann K, Lai FA, Murray D, McLaughlin S. Binding of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-zeta (PLC-zeta) to phospholipid membranes: potential role of an unstructured cluster of basic residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:16644–16653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdener F, Dangelmaier C, Ashby B, Kunapuli SP, Daniel JL. Activation of phospholipase Cγ2 by tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;62:672–679. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Jhon D, Lee C, Ryu SH, Rhee SG. Removal of the carboxyl-terminal region of phospholipase C-β1 by calpain abolishes activation by Gαq. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:3710–3714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechulek T, Rehlen T, Walliser C, Vatter P, Moepps B, Gierschik P. Isozyme-specific stimulation of phospholipase C-γ2 by Rac GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38923–38931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG. Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:281–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R, Matsuda M, Perisic O, Bravo J, Paul A, Jones NP, Light Y, Swann K, Williams RL, Katan M. Tyrosine residues in phospholipase Cγ2 essential for the enzyme function in B-cell signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47982–47992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders CM, Larman MG, Parrington J, Cox LJ, Royse J, Blayney LM, Swann K, Lai FA. PLC-ζ: a sperm-specific trigger of Ca2+ oscillations in eggs and embryo development. Development. 2002;129:3533–3544. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel P, Camps M. Activation of a phospholipase Cβ2 deletion mutant by limited proteolysis. Biochem. J. 1998;330:461–468. doi: 10.1042/bj3300461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CC, Dobson W, Botelho RJ, Coady-Osberg N, Chavrier P, Knecht DA, Heath C, Stahl P, Grinstein S. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis directs actin remodeling during phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:139–149. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert JP, Wing MR, Snyder JT, Gershburg S, Sondek J, Harden TK. RhoA activates purified phospholipase C-ε by a guanine nucleotide-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47992–47997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya F, Poulin B, Kim YJ, Rhee SG. Mechanism of tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of phospholipase C-γ1. Tyrosine 783 phosphorylation is not sufficient for lipase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32181–32190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu RS, Clough RR, Bhullar RP. Regulation of phospholipase C-δ1 through direct interactions with the small GTPase Ral and calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21933–21941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JT, Singer AU, Wing MR, Harden TK, Sondek J. The pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-β2 as an effector site for Rac. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21099–21104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Hille B. Regulation of ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K, Saunders CM, Rogers NT, Lai FA. PLC-ζ: a sperm protein that triggers Ca2+ oscillations and egg activation in mammals. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006;17:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo GL, Boyer JL, Morris AJ, Harden TK. Purification of an AlF4− and G-protein βγ-subunit-regulated phospholipase C-activating protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:14217–14225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo GL, Paterson A, Boyer JL, Nicholas RA, Harden TK. Molecular cloning, expression and regulatory activity of Gα11- and βγ-subunit-stimulated phospholipase C-β from avian erythrocytes. Biochem. J. 1996;316:559–568. doi: 10.1042/bj3160559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Pentyala S, Elliott JT, Dowal L, Gupta E, Rebecchi MJ, Scarlata S. Selective interaction of the C2 domains of phospholipase C-β1 and -β2 with activated Gαq subunits: an alternative function for C2-signaling modules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999a;96:7843–7846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Pentyala S, Rebecchi MJ, Scarlata S. Differential association of the pleckstrin homology domains of phospholipases C-β1, C-β2, and C-δ1 with lipid bilayers and the β γ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins. Biochemistry. 1999b;38:1517–1524. doi: 10.1021/bi982008f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Dowal L, El-Maghrabi MR, Rebecchi M, Scarlata S. The pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-β2 links the binding of Gβγ to activation of the catalytic core. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:7466–7469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing MR, Snyder JT, Sondek J, Harden TK. Direct activation of phospholipase C-ε by Rho. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41253–41258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Jiang H, Katz A, Simon MI. Identification of critical regions on phospholipase C-β1 required for activation by G-proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:3704–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue G, Malik B, Eaton DC. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) stimulates epithelial sodium channel activity in A6 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11965–11969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Neer EJ. Reassembly of phospholipase C-β2 from separated domains: analysis of basal and G protein-stimulated activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2503–2508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Craciun LC, Mirshahi T, Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Jin T, Logothetis DE. PIP2 activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron. 2003;37:963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Wing MR, Sondek J, Harden TK. Molecular cloning and characterization of PLC-η2. Biochem. J. 2005;391:667–676. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Sondek J, Harden TK. Activation of human phospholipase C-η2 by Gβ γ. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4410–4417. doi: 10.1021/bi800044n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplemental Data include Supplemental Experimental Procedures, three figures, and one table and can be found with this article online at http://www.molecule.org/cgi/content/full/31/3/383/DC1/.