Summary

Parasitoid wasps produce virulence factors that bear significant resemblance to viruses and have the ability to block host defense responses. The function of these virulence factors, produced predominantly in wasp venom glands, and the ways in which they interfere with host development and physiology remain mysterious. Here, we report the discovery of a specialized system of canals in venom glands of five parasitoid wasps that differ in their infection strategies. This supracellular canal system is made up of individual secretory units, one per secretory cell. Individual units merge into the canal lumen. The membrane surface of the proximal end of each canal within the secretory cell assumes brush border morphology, lined with bundles of F-actin. Systemic administration of cytochalasin D compromises the integrity of the secretory unit. We show a dynamic and continuous association of p40, a protein of virus-like particles from a Drosophila parasitoid, L. heterotoma, with the canal and venom gland lumen. Similar structures in three Leptopilina species and Ganaspis xanthopoda, parasitoids of Drosophila spp., and Campoletis sonorenesis, a parasitoid of Heliothis virescens, suggest that this novel supracellular canal system is likely to be a common trait of parasitoid venom glands that is essential for efficient biogenesis and delivery of virulence factors.

Keywords: host, pathogen, parasitoid, venom gland, virulence, brush border, canal

INTRODUCTION

Parasitoid insects lead a peculiar lifestyle, characterized by a parasitic larva, which develops at the expense of a host (often, another developing insect) that it eventually kills. The adult parasitoid is free-living and actively searches for new hosts to infect. Parasitoids are very common among many insect orders, especially in the Hymenoptera. Approximately 10–20% of all insects are believed to be parasitoid wasps. Their specific and obligate relationships with hosts make this unusual class of pathogens attractive biological control agents (Pennacchio and Strand, 2006).

During oviposition, endoparasitic Hymenoptera produce and deliver venom, mutualistic viruses, polydnaviruses (PDVs) or virus-like particles (VLPs) into their hosts. These factors are produced in the female reproductive tract or within organs associated with it. Based on ultrastructural studies, both PDVs and VLPs are described as virus-like, but they have distinct morphology, and are produced in different tissues. Both PDVs and VLPs effectively block the activation of the host's immune defenses (notably encapsulation and melanization), conferring evolutionary advantage to parasitoids (Rizki and Rizki, 1990; Chiu et al., 2001; Whitfield and Asgari, 2003; Labrosse et al., 2005; Morales et al., 2005; Pennacchio and Strand, 2006).

In contrast to PDVs, VLPs appear not to encapsidate nucleic acid. Furthermore, whereas PDVs are synthesized and assembled in the nuclei of calyx cells, VLPs are detected in the lumen of the venom gland and reservoir (Webb and Strand, 2005; Morales et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2006).

The biogenesis and origin of PDVs has been the subject of much investigation. Recent characterization of polydnaviral genomes (Webb and Strand, 2005) has provided insight into their relationship with their respective wasps. Although the relationship of PDVs with their wasps is somewhat controversial, there is general agreement that PDVs are vectors that deliver the wasp's genetic material into the host and are likely to have evolved from a mutualistic or symbiotic ancestral insect virus (Federici and Bigot, 2003; Whitfield and Asgari, 2003). The biogenesis and composition of VLPs are only now being unraveled (see below), and their origin is not well understood.

Campoletis sonorensis (Ichneumonidae), a parasitoid of lepidopteran pests of corn, cotton and several vegetable crops, has a well-studied PDV (Campoletis sonorensis ichnovirus; CsIV), which replicates from an integrated provirus in the ovarian calyx cells (Stoltz and Vinson, 1979; Webb and Strand, 2005). The contents of C. sonorensis venom gland are, however, less well characterized, although available evidence (Webb and Summers, 1990; Luckhart and Webb, 1996) suggests that, like the VLPs of Drosophila parasitoids (Rizki and Rizki, 1990), C. sonorensis venom proteins perform immune suppressive functions, which are important for parasitoid survival.

Wasps of the genus Leptopilina spp. infect Drosophila spp. and produce VLPs (Rizki and Rizki, 1990; Labrosse et al., 2005; Morales et al., 2005; Schlenke et al., 2007). The venom glands of the highly-virulent sister species, L. heterotoma and L. victoriae, produce polymorphic, 300 nm-wide, spiked VLPs (Rizki and Rizki, 1990; Morales et al., 2005). VLP spikes interact with immune-active blood cells (lamellocytes) of the host, leading to their lysis (Rizki and Rizki, 1990; Morales et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2006). In each case, lamellocyte lysis is attributed to the presence of a protein of about 40 kDa [p40 in L. heterotoma and p47.5 in L. victoriae (Chiu et al., 2006)]. The activities of venom gland factors, including VLPs (Chiu and Govind, 2002), provide one possible explanation for the broad host range observed for L. heterotoma (Schlenke et al., 2007).

In addition to VLPs, a filamentous virus has been identified in the ovipository apparatus of specific strains of L. boulardi females. Their presence has been correlated to the development of superparasitic behavior by the infected parasitoid wasps (Varaldi et al., 2006). L. boulardi-17, is also a highly virulent and pathogenic wasp strain that produces a variety of products including VLPs in its venom gland. Unlike L. heterotoma venom, L. boulardi-17 venom is unable to lyse host lamellocytes. The host range of L. boulardi-17 is restricted, relative to that of L. heterotoma. Significantly, these wasps with different infection strategies yield remarkably distinct host responses, as measured by genome-wide gene expression changes (Schlenke et al., 2007).

Thus, the female reproductive tracts of parasitoid wasps, and the organs associated with it, represent a privileged environment for the production of a variety of virulence factors. These organs also house microscopic entities that play a critical role in host–parasitoid interactions. The characterization of these organs is, therefore, important for understanding not only the parasitoid–host interaction in the context of the host's immune physiology, but also the role of VLPs, viruses and symbionts in the co-evolution of the host and its parasitoids.

To understand the biogenesis and nature of virulence factors produced in venom glands, we compared the structures of these organs from parasitoid species that produce either PDVs or VLPs. We show that, regardless of their infection strategy, venom glands from all the examined species have a supracellular system of canals. Within the secretory cell itself, the membrane surface of the proximal end of each canal has a brush border morphology, lined with bundles of polymerized actin. We infer the physiological function of this novel canal system from a study of the close and continuous association of p40, an abundant and functionally important VLP component of L. heterotoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insect stocks

L. heterotoma strain Lh14 and L. boulardi strain Lb17 were described by Schlenke et al. (Schlenke et al., 2007); L. victoriae by Morales et al. (Morales et al., 2005); and G. xanthopoda by Melk and Govind (Melk and Govind, 1999). Wasp species were maintained on the y w strain of Drosophila melanogaster and have been previously described (Morales et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2006; Sorrentino et al., 2002). C. sonorensis was reared on Heliothis virescens.

Venom gland dissection and immunolocalization

Venom glands from female wasps of the different species were dissected under a stereomicroscope in PBS (pH 7.0), fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde (in 2% sucrose PBS solution, pH 7.6), rinsed 3 times in PBS, stained with TRITC (tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate)-labeled phalloidin for 20 min to highlight actin filaments (0.5 μg ml–1; Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Samples were rinsed three times in PBS, and counterstained with the nuclear stain DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; 300 nmoll–1; Invitrogen), and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

L. heterotoma VLP protein p40 distribution was visualized with a mouse polyclonal antiserum obtained after injection of purified VLP preparations. It has been shown to be effective in a number of studies. (1) This serum specifically reacts with the most abundant 40 kDa protein in denatured protein preparations of purified L. heterotoma VLPs, and cross reacts with 47.5 kDa protein from purified L. victoriae VLPs (Chiu et al., 2006). (2) Anti-p40 antigen is localized to the spikes of mature L. heterotoma or L. victoriae VLPs, as well as on (or in the vicinity of) VLPs at different stages of biogenesis from the venom gland [transmission electron microscopy studies (Chiu et al., 2006)]. (3) Anti-p40 antibody reacts with hemocytes from infected animals, but not with hemocytes from control animals (Chiu et al., 2006), consistent with the presence of intact VLPs within these cells (Rizki and Rizki, 1994). (4) In in vitro experiments, this antiserum also inhibits lysis of host hemocytes, an activity previously associated with VLPs (Rizki and Rizki, 1990; Chiu et al., 2006). Thus anti-p40 is used to track VLPs from initial stages of protein synthesis in secretory cells, their biogenesis in the venom gland, and after oviposition within host hemocytes.

After fixation, samples for immunolocalization were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS (pH 7.4) at 4°C, rinsed three times and incubated with blocking solution (2% BSA, 0.01% Tween20 in PBS, pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37°C, and incubated with anti-p40 antibody (1:500 dilution in blocking solution) (Chiu et al., 2006) for 2 h at 37°C. Samples were rinsed five times with blocking solution and incubated with a FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate)-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200 in blocking solution; Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were then counterstained with TRITC-phalloidin and DAPI and mounted in Vectashield. Samples were viewed with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope at room temperature.

Three-dimensional reconstructions

Z stacks of confocal images were loaded to Amira 3.1.1 (Mercury Computer Systems, www.tgs.com), the appropriate voxel size was chosen and images were processed to obtain the isosurfaces display. Image resampling was performed to obtain the desired resolution in order to emphasize the most important features in the image. Images were saved as tagged image file format files with Adobe Photoshop (6.0).

Transmission electron microscopy sample preparation

Venom glands dissected from female wasps were prepared for ultra-structure analysis as described by Morales et al. (Morales et al., 2005). Images were collected with a Zeiss transmission electron microscope (EM902) at room temperature.

Cytochalasin treatment

Ten L. heterotoma-14 female wasps were fed cytochalasin D (1 mg ml–1 diluted in a 1:1 honey:water solution) for 12 h. Venom glands were dissected and p40 immunolocalization was performed as described above.

RESULTS

In this study we focused on highly pathogenic wasp species of the genus Leptopilina that effectively suppress host immunity [Figitidae (Schlenke et al., 2007)]. These wasps and Ganaspis xanthopoda [Figitidae (Melk and Govind, 1999; Chiu et al., 2001)] regularly infect larval stages of Drosophila species. The free-living adult females (Fig. 1A–D) are roughly half the size of the adult D. melanogaster, but significantly smaller than adults of Campoletis sonorensis, an ichneumonid parasitoid (Fig. 1E) that infects some larval Lepidoptera species.

Fig. 1.

Parasitoid wasp species. Relative size of parasitoids: female L. heterotoma, L. boulardi, L. victoriae and G. xanthopoda infect Drosophila larvae; C. sonorensis infects H. virescens caterpillars, which are ten-times larger than fly larvae. Scale bar, 1.5 mm for all panels.

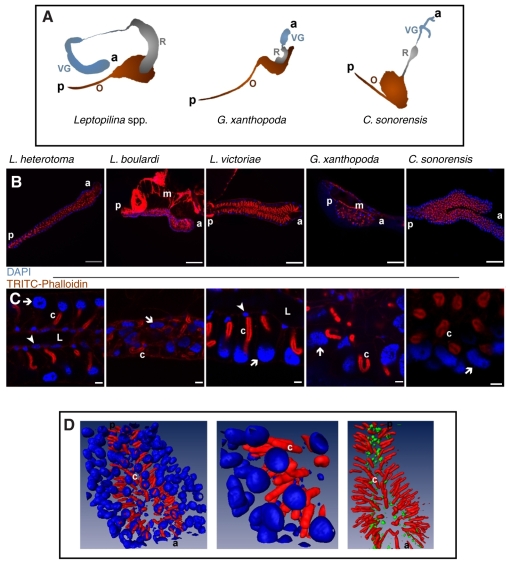

Organization of canals within venom gland

The venom apparatus of the wasp can be divided into three main regions. The posterior end bears a long chitinous ovipositor, responsible for the delivery of eggs and venom into the host, a reservoir in which the venom is stored, and a venom gland, which produces and secretes the components of the venom. All the species considered here share this tripartite organization (Fig. 2A), even though some features (e.g. shape and size of the venom gland, length of the duct connecting the gland to the reservoir, or size of the reservoir itself) differ.

Fig. 2.

Organization of wasp venom glands. (A) Overall organization of the venom apparatus. From posterior (p) to anterior (a) are, ovipositor (O), reservoir (R) and venom gland (VG). The venom gland and the reservoir are joined by a narrow connecting duct. (B) Confocal images of venom glands from parasitoids showing diversity in shape and size: Leptopilina spp. have elongated glands, the G. xanthopoda gland is sac-shaped, whereas that of C. sonorensis is branched. F-actin-rich structures (red), and occasionally, muscles (m) connected to the ovipositor are visible. a, anterior; p, posterior. Scale bar, 100 μm. Objective: Plan-Apochromat ×20/0.8. (C) Secretory cells with large nuclei (arrows) contain the canal-like structures (c); intimal layer cells, with small nuclei (arrowheads, nuclei not visible in all images), line the lumen (L) of the venom gland. Scale bar, 5 μm. Objective: Plan-Apochromat ×63/1.4, oil differential interference contrast (DIC) optics. (D) Three-dimensional reconstruction of L. heterotoma venom gland, secretory cell nuclei (blue), actin canals (c, red) and intimal cell layer (green). a, anterior; p, posterior.

Confocal images of DAPI/TRITC-phalloidin-labeled venom glands show that despite differences in size and shape, all glands share the presence of prominent actin-rich structures inside their cells (Fig. 2B). In venom glands of all five wasps, two different cell types are distinguished: first, small and narrow cells that line the lumen of the venom gland. We have previously referred to this layer of cells as the intimal layer in venom glands of L. heterotoma and L. victoriae (Morales et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2006). This cell layer is apposed to a second, peripheral layer of larger, evidently polyploid, secretory cells, which contain the actin-lined canals (Fig. 2B). A three-dimensional reconstruction of L. heterotoma venom gland confirms that each secretory cell only has one unbranched canal that originates roughly perpendicular to the long axis of the venom gland (Fig. 2C,D). The large nucleus of the secretory cell is found peripherally, whereas nuclei of the smaller cells of the intimal layer are located deeper within the organ (Fig. 2D).

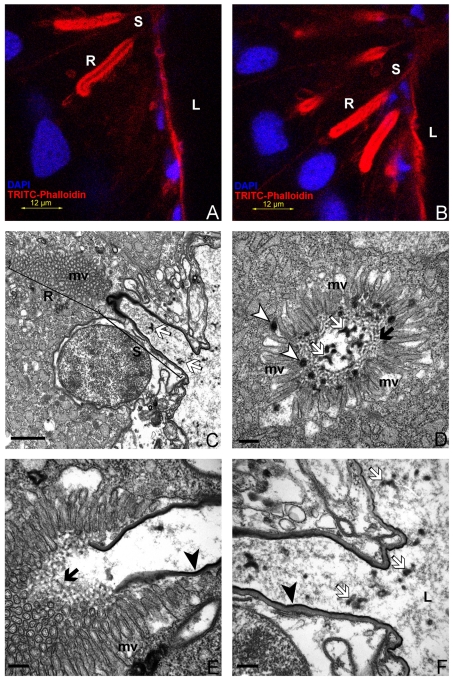

A brush border lines the proximal end of the canal

High magnification confocal images of the L. heterotoma gland reveal that there are two distinct regions in the canals: the proximal portion (proximal to site of origin), roughly 20 μm in length, positioned deep within the secretory cell, which is strongly positive for TRITC-phalloidin (rough canal, R), and a distal portion, roughly 10μm long, which is closer to the lumen of the gland, where TRITC-phalloidin staining is faint (smooth canal, S; Fig. 3A,B).

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructure of Leptopilina spp. venom gland. (A,B) Confocal images of L. heterotoma venom gland, in which the rough (R) and the smooth (S) parts of the canals are distinguishable by the different TRITC-phalloidin staining intensity. L, gland lumen. Objective: Plan-Apochromat ×63/1.4, oil DIC optics. (C) Transmission electron micrograph of one L. victoriae F-actin-lined canal, with rough, microvillar (R) and smooth, cuticle-lined (S) portions. Cross-sectioned microvilli (mv) are visible in the rough portion and virus-like particle (VLP) precursors (white arrows) are found in the canal lumen. Scale bar, 1.1 μm. Magnification: ×7000, 80 KeV. (D) Transmission electron micrograph of a cross-section of one L. victoriae canal lined by microvilli (mv). The black arrow points to a putative mesh-like matrix; arrowheads indicate electron-dense structures between the microvilli. In addition, VLP precursors (white arrows) are observed in the canal lumen. Scale bar, 0.4 μm. Magnification: ×20,000, 80 KeV. (E) Transmission electron micrograph of one L. victoriae canal showing the region where the rough portion transitions into the cuticle-lined smooth portion (black arrowhead). The rough region is lined with a mesh-like matrix (arrow) abutting the microvilli (mv). Scale bar, 0.25 μm. Magnification: ×30,000, 80 KeV. (F) Transmission electron micrograph of one L. victoriae smooth canal meeting the gland lumen (L). VLP precursors (white arrows) and cuticle lining the canal (black arrowhead) are clearly visible. Scale bar, 0.25 μm. Magnification: ×30,000, 80 KeV.

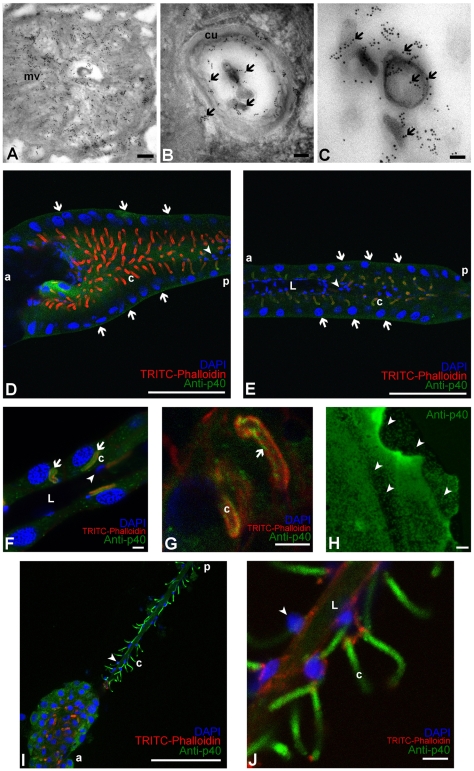

Detailed electron microscopy of L. victoriae (Morales et al., 2005) and L. heterotoma (Chiu et al., 2006) venom glands shows a very similar organization of canal structures in these species. The rough canal is lined by numerous microvillous folds, each of which is 0.4 μm in length (Fig. 3C,D, mv). This surface organization is reminiscent of the brush borders found in intestinal and other cells with secretory or absorptive functions. Cross sections of the rough canal reveal that microvilli surround the lumen of the canal completely (Fig. 3D, mv). The canal lumen has electron-dense particles (Fig. 3D). These particles are strikingly similar to structures found in rough canals of L. heterotoma, which, in immuno-EM studies, stain positively with anti-p40 antibody (Fig. 4) (Chiu et al., 2006) (Fig. 4A–C). The peripheral region of the canal lumen itself is lined with a mesh-like membranous structure in which electron-dense particles are also found (Fig. 3D). We note that the `mesh' appearance may arise simply from a tangential section of the very tips of tightly-packed microvilli, and may not be an additional structure as interpreted here.

Fig. 4.

p40 localization in L. heterotoma venom gland. (A) Transmission electron micrograph with anti-p40 immunogold staining of the rough canal in cross section. p40 (black dots) is localized in the microvillar area (mv). Scale bar, 0.25 μm. Magnification: ×30,000, 80 KeV. (B) Transmission electron micrograph with anti-p40 immunogold staining of a smooth canal in cross section. p40 (arrows) is in the lumen of the canal, close to the walls and in the center, p40 is associated with larger electron-dense virus-like particle (VLP) precursors. cu, cuticle lining the canal. Scale bar, 90 nm. Magnification: ×85,000, 80 KeV. (C) Transmission electron micrograph of anti-p40-labelled section of the lumen of the venom gland. p40 (arrows) signal is predominantly around assembling VLPs. Scale bar, 0.05 μm. Magnification: ×40,000, 80 KeV. (D) Confocal image of the anterior part of the venom gland. p40 (green) is found peripherally in the secretory cell cytoplasm around the nuclei (arrows), but the p40 signal in and around the canals is not as strong (c, red). Smaller nuclei of cells of the intimal layer (arrowhead) are visible in the center of the gland. The p40 signal in the body of the gland is from the gland lumen, which is positioned below the focal plane of this image. a, anterior; p, posterior. Scale bar, 100 μm. Objective: EC Plan-Neofluar ×40/1.30, oil DIC optics. (E) Confocal image of the posterior part of the venom gland. The secretory cells, cells of the intimal layer and the venom gland lumen (L) are labeled as in D. The p40 signal (green), also present within the cytoplasm of the secretory cells (arrows), is concentrated around the canals. a, anterior; p, posterior. Scale bar, 100 μm. Objective: EC Plan-Neofluar 40x/1.30, oil DIC optics. (F,G) Confocal images of the posterior part of the venom glands. p40 (arrows) is found in the lumen of the canals (F) or colocalizing with the F-actin (c, red; G). Labeling as in E. Scale bar, 5 μm. Objective: Plan-Apochromat ×63/1.4, oil DIC optics. (H) Confocal images of the venom fluid stained with anti-p40 antibody (green). The p40 signal has a spot-like pattern (arrowheads). Scale bar, 5 μm. Objective: EC Plan-Neofluar ×40/1.30, oil DIC optics. (I,J) Confocal images of a venom gland dissected from a cytochalasin-treated L. heterotoma. Labeling is as in E. In the anterior part, secretory cells are shrunk (I) and actin staining around the canals (c) is weak. In the posterior portion (higher magnification in J) secretory cells are not visible, whereas the entire canals (c) persist, even though the rough portion (corresponding to the microvillar region) is not evident. a, anterior; p, posterior. Scale bar, 100 μm. Objective: EC Plan-Neofluar ×40/1.30, oil DIC optics. (J) Confocal image of a venom gland dissected from a cytochalasin-treated L. heterotoma. p40 (green)-filled canals (c) hang from the gland lumen (L), which is outlined by cells of the intimal layer (arrowhead). Labeling as in E. Scale bar, 5 μm. Objective: EC Plan-Neofluar 40x/1.30, oil DIC optics.

The distal, smooth portion of the canal is not lined with microvilli. Instead, the smooth canal is lined with a chitinous layer. A closer examination of the region where the rough region ends and the smooth region begins, reveals an abrupt transition from the highly folded microvillar membrane region to the tightly extended chitinous covering (Fig. 3C,E, arrowhead). The smooth canal opens directly into the lumen of the venom gland (Fig. 3C,F). Thus, VLP contents synthesized in secretory cells are released directly into the venom gland lumen (L, Fig. 3F) (Morales et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2006). The chitin covering lining the smooth canal (Fig. 3F, arrowhead) appears to be continuous with the lining of the venom gland lumen.

The entire canal structure consists of a merger of two distinct structural entities: (1) the rough canal containing a highly modified membrane adapted for efficient trafficking of the molecular components, which will presumably assemble into VLPs, and (2) the smooth canal that may simply be an invagination of the extracellular space that is tailored for efficient delivery. We speculate that VLP precursors and partially assembled particles continue to undergo assembly and maturation once components of secretory cells are delivered into the venom gland lumen (Morales et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2006) (Fig. 3F).

Secretion dynamics of the venom protein p40

To understand the function of canals in the secretion and delivery of VLP components, we studied the association of p40, a previously identified virulence factor from L. heterotoma VLPs (see Materials and methods) (Chiu et al., 2006). Immunogold staining of p40 in the venom gland of L. heterotoma demonstrates its association with (1) the microvillar region of the rough canals (Fig. 4A, mv), (2) along the wall and within the lumen of the smooth canal (Fig. 4B), and (3) with VLP precursors in the lumen of the venom gland (Fig. 4C). Thus, VLP precursors produced in secretory cells are secreted into the rough canal and are delivered into the venom gland lumen via the smooth canal.

Indirect immunofluorescence labeling of p40 throughout the organ (Fig. 4D–H) reveals differences in p40 localization within the gland. In cells of the anterior end of the venom gland, p40 is widely distributed through the cytoplasm of the secretory cells, whereas little, if any, p40 is detected in the immediate proximity of or within the canals (Fig. 4D). In cells at the posterior end of the same gland, p40 is strongly associated with canals (Fig. 4E). At higher magnification, these posterior secretory cells also show p40 localized in scattered spots in the cytoplasm, but the staining is concentrated mainly within the canals, either colocalizing with the actin-rich microvilli or inside the lumen (Fig. 4F,G). When the venom fluid was collected on a slide and stained with anti-p40 antibody, p40 signal was strong and spotty (Fig. 4H, arrowheads). This signal probably reflects the association of p40 with VLPs as observed in transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 4C). Variations in p40 localization in the venom gland most probably reflect the physiological and functional dynamics of the organ and the association of p40 with different stages of VLP biogenesis.

In order to assess the role of the actin scaffold in the structural maintenance of the canal system, we tested the effect of systemically administered cytochalasin D (see Materials and methods), an inhibitor of actin polymerization (Blankson et al., 1995). In general, the overall integrity of the wasp venom gland is compromised and the size of the venom gland is significantly reduced (Fig. 4I) in treated animals. Secretory cells in the posterior portion of such venom glands are no longer present; here the canals, devoid of their actin sheath, hang from the inner core of the gland in which the venom gland lumen is still outlined by cells of the intimal layer. This observation suggests that the cuticular chitinous lining of the smooth canals helps support these canals. p40 staining (Fig. 4I,J) is concentrated in the lumen of the canals, whereas the lumen of the gland is only weakly positive for the staining. These results are consistent with the idea that the actin-rich microvillar region, which normally surrounds the canals, regulates the rate of molecular traffic between the secretory cell and the canal lumen. This proximal (rough) region of the canal can, in fact, be considered a specialized zone of the venom gland lumen itself, where VLP components accumulate to sufficiently high concentration and undergo early steps of assembly.

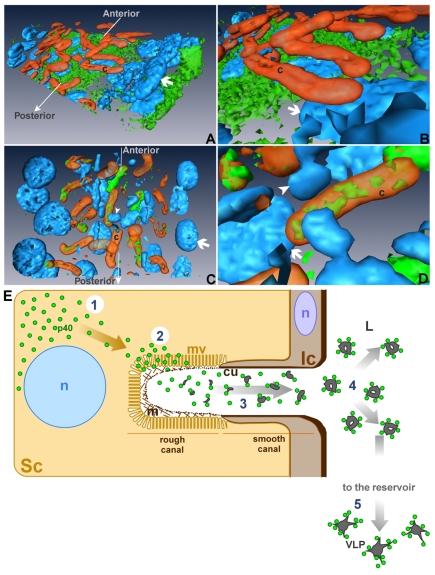

A digital reconstruction of the isosurfaces (obtained from Z stacks of confocal images; Fig. 5A,B) supports our interpretation of results from EM and confocal studies. It also confirms that the distribution of p40 is different in the anterior and posterior parts of the venom gland, as seen in Fig. 4D,E above. In cells of the posterior-most part of the gland, p40 signal is found almost exclusively around (Fig. 5C) or inside (Fig. 5C,D) the canals.

Fig. 5.

Model of synthesis and secretion of p40. (A,B) Three-dimensional reconstruction of a section of the anterior region of an L. heterotoma venom gland. p40 (green) is mainly localized to the outermost part of the secretory cells around nuclei (arrow). Actin canals (c) are positioned deeper in the cytoplasm where the concentration of p40 is lower. A close-up view (B) highlights the absence of p40 (green) within the canals (c) of this cell. (C,D) Three-dimensional reconstruction of a section of the posterior region of an L. heterotoma venom gland. p40 (green) is closely associated to the actin canals (c), either surrounding them or contained within their lumen. A close-up view (D) confirms that p40 (green) is found inside the lumen of some canals. The arrow points to a secretory cell nucleus; the arrowhead points to the nucleus of a cell of the intimal layer. (E) Organization of a secretory unit in the context of p40 synthesis, secretion and assembly of virus-like particles (VLPs). 1. p40 is synthesized in the perinuclear region of secretory cells (Sc). 2. p40 reaches the microvillar region (mv) of the canals where it is secreted into the canal lumen, passing through a putative extracellular mesh (m). 3. In the canal lumen, p40 associates with other components to assemble into VLP precursors. 4. VLP precursors containing p40 once released into the venom gland lumen (L), undergo additional structural changes. 5. Aggregates containing p40 travel along the gland lumen to reach the reservoir, where they mature into VLPs. Ic, cell of the intimal layer; n, nuclei; cu, cuticle.

DISCUSSION

A model of virulence factor synthesis and secretion in the parasitoid venom gland

Based on our combined structural and functional evidence from L. heterotoma p40 localization, we propose that the wasp's venom gland contains a system of secretory units (Fig. 5E), each composed of (1) a secretory cell, responsible of the production and release of wasp virulence agents, (2) a canal connecting the secretory cell with the lumen of the venom gland, and (3) a cell of the intimal layer, which surrounds the distal portion of the canal where it opens towards the lumen of the gland.

We propose a model (Fig. 5E) for the role of canals in the assembly and delivery of virulence factors. p40 is initially produced in the perinuclear region of secretory cell cytoplasm (Fig. 5A,B). It then moves towards the secretory cell membrane in the microvillar region of the canals (Fig. 5C,D). Here, p40 is secreted into the canal lumen, passing through a putative extracellular mesh. Once in the canal lumen, p40 associates with other components to assemble into VLP precursors, which undergo additional structural changes as they are released into the venom gland lumen. Aggregates, containing p40 travel along the gland lumen to reach the reservoir, where they eventually mature into VLPs.

A novel supracellular system of canals in the venom gland of parasitoid wasps

The many species of Hymenoptera (bees, ants and wasps) vary widely in lifestyle, behavior and geographic distribution. Virtually, all Hymenoptera have venom glands, but the nature and function of the venom components can vary from pain-inducing defense molecules, hormone-like development regulators, to immune suppressive factors (Gnatzy and Volknandt, 2000). Despite this functional diversity, the organization of the secretory unit appears to be conserved among species with very different lifestyles. Secretory units from venom glands of the free-living Apis mellifera (Roat et al., 2006), the gall-inducer cynipoid wasps (Vårdal, 2006), and other parasitoids (Edson et al., 1982; Quicke et al., 1992; Uçkan, 1999; Gnatzy and Volknandt, 2000; Britto and Caetano, 2003; Wan et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2007) have previously been reported. Interestingly, Noirot and Quennedey (Noirot and Quennedey, 1974) have described similar canals in the class III epidermal gland cells from many insects, using conventional microscopy techniques.

Our study reveals for the first time the scope of canal organization at the whole organ level, and at the same time, correlates the ultrastructural components of the secretory unit of the venom gland to the steps of release and sub-assembly of specific VLP components. The organization of the membrane into a brush border suggests the need for efficient exchange between intracellular and extracellular environments, consistent with the secretory function of the organ. The unique organization where rough canal (brush border) invaginates into the cytoplasm of the secretory cells appears to be an adaptation to increase the surface to volume ratio of the secretory cells. By confining the membrane area that is predominantly involved in the exchange process within the cell volume, the brush border organization helps keep the size of the venom gland small.

Venom glands are easy to isolate and secretory units possess a distinctive morphology that is manipulatable by systemic administration of drugs. These features offer an opportunity to study the unique structural aspects of the canal system, and the assembly and release of particles at a whole organ level.

This study was supported by the National Research Initiative of the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, grant numbers: 2006-03817 and 2009-35302-05277, NIH (NIGMS S06 GM08168, GM056833-08 and G12-RR03060), HHMI (52005115) and PSC-CUNY. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

References

- Blankson, H., Holen, I. and Seglen, P. O. (1995). Disruption of the cytokeratin cytoskeleton and inhibition of hepatocytic autophagy by okadaic acid. Exp. Cell Res. 218, 522-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto, F. B. and Caetano, F. H. (2003). Ultramorphology of the venom glands and its histochemical relationship with the convoluted glands of Polistes versicolor (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Microsc. Acta 12, 473-474. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, H. and Govind, S. (2002). Natural infection of D. melanogaster by virulent parasitic wasps induces apoptotic depletion of hematopoietic precursors. Cell Death Differ. 9, 1379-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, H., Sorrentino, R. P. and Govind, S. (2001). Suppression of the Drosophila cellular immune response by Ganaspis xanthopoda. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 484, 161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, H., Morales, J. and Govind, S. (2006). Identification and immuno-electron microscopy localization of p40, a protein component of immunosuppressive virus-like particles from Leptopilina heterotoma, a virulent parasitoid wasp of Drosophila. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 461-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edson, K. M., Barlin, M. R. and Vinson, S. B. (1982). Venom apparatus of braconid wasps: comparative ultrastructure of reservoirs and gland filaments. Toxicon 20, 553-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federici, B. A. and Bigot, Y. (2003). Origin and evolution of polydnaviruses by symbiogenesis of insect DNA viruses in endoparasitic wasps. J. Insect Physiol. 49, 419-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnatzy, W. and Volknandt, W. (2000). Venom gland of the digger wasp Liris niger: morphology, ultrastructure, age-related changes and biochemical aspects. Cell Tissue Res. 302, 271-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrosse, C., Stasiak, K., Lesobre, J., Grangeia, A., Huguet, E., Drezen, J. M. and Poirie, M. (2005). A RhoGAP protein as a main immune suppressive factor in the Leptopilina boulardi (Hymenoptera, Figitidae)-Drosophila melanogaster interaction. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35, 93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckhart, S. and Webb, B. A. (1996). Interaction of a wasp ovarian protein and polydnavirus in host immune suppression. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 20, 1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melk, J. P. and Govind, S. (1999). Developmental analysis of Ganaspis xanthopoda, a larval parasitoid of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 1885-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales, J., Chiu, H., Oo, T., Plaza, R., Hoskins, S. and Govind, S. (2005). Biogenesis, structure, and immune-suppressive effects of virus-like particles of a Drosophila parasitoid, Leptopilina victoriae. J. Insect Physiol. 51, 181-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noirot, C. and Quennedey, A. (1974). Fine structure of insect epidermal glands. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 19, 61-80. [Google Scholar]

- Pennacchio, F. and Strand, M. R. (2006). Evolution of developmental strategies in parasitic Hymenoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51, 233-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quicke, D. L. J., Tunstead, J., Vincente Falco, J. and Marsh, P. M. (1992). Venom gland and reservoir morphology in the Doryctinae and related braconid wasps (Insecta, Hymenoptera, Braconidae). Zool. Scr. 21, 403-416. [Google Scholar]

- Rizki, R. M. and Rizki, T. M. (1990). Parasitoid virus-like particles destroy Drosophila cellular immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 8388-8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizki, T. M. and Rizki, R. M. (1994). Parasitoid-induced cellular immune deficiency in Drosophila. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 712, 178-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roat, T. C., Cornelio Ferreira Nocelli, R. and da Cruz Landim, C. (2006). The venom gland of queens of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera, Apidae): morphology and secretory cycle. Micron 37, 717-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenke, T., Morales, J., Govind, S. and Clark, A. G. (2007). Contrasting infection strategies in generalist and specialist wasp parasitoids of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathog. 3, 1486-1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino, R. P., Carton, Y. and Govind, S. (2002). Cellular immune response to parasite infection in the Drosophila lymph gland is developmentally regulated. Dev. Biol. 243, 65-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz, D. B. and Vinson, S. B. (1979). Viruses and parasitism in insects. Adv. Virus Res. 24, 125-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uçkan, F. (1999). The morphology of the venom apparatus and histology of venom gland of Pimpla turionellae (L.) (Hym: Ichenumonidae) females. Tr. J. Zool. 23, 461-466. [Google Scholar]

- Varaldi, J., Petit, S., Boulétreau, M. and Fleury, F. (2006). The virus infecting the parasitoid Leptopilina boulardi exerts a specific action on superparasitism behaviour. Parasitology 132, 747-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vårdal, H. (2006). Venom gland and reservoir morphology in cynipoid wasps. Arthropod. Struct. Dev. 35, 127-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z. W., Wang, H. Y. and Chen, X. X. (2006). Venom apparatus of the endoparasitoid wasp Opius caricivorae Fischer (Hymenoptera: Braconidae): morphology and ultrastructure. Microsc. Res. Tech. 69, 820-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, B. A. and Strand, M. R. (2005). The biology and genomics of polydnaviruses. In Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science (ed. L. I. Gilbert, K. Iatrou and S. S. Gill), pp. 323-360. San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

- Webb, B. A. and Summers, M. D. (1990). Venom and viral expression products of the endoparasitic wasp Campoletis sonorensis share epitopes and related sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 4961-4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, J. B. and Asgari, S. (2003). Virus or not? Phylogenesis of polydnaviruses and their wasp carriers. J. Insect Physiol. 49, 397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Y., Ye, G. Y. and Hu, C. (2007). Morphology and ultrastructure of the venom apparatus in the endoparasitic wasp Pteromalus puparum (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). Micron 39, 926-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]