Abstract

This article provides an overview of hospital-based rates of caesarean delivery in 18 Arab countries and observes the association between these rates and selected demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Data on caesarean section (CS) were based on two main sources, the most recent national hospital-based surveys undertaken in each country and published studies based on hospital-based samples. Particularly, high levels of caesarean delivery (above 20 %) were found in Egypt with a rate of 26% in 2003 followed by Sudan with a rate of 20% in 1993. Overall, findings indicate an increasing trend of caesarean’s rate delivery in the region. Six countries and the West Bank had caesarean rates above 15% and the remaining 11 countries as well as Gaza had caesarean rates ranging between 5-15%. Results show a positive association between CS rates and mother’s age and education. Higher CS rates were also found among urban residents as compared to their rural counterparts. Policies aiming at reducing surgical deliveries should seek to identify and address these risk factors.

Introduction

During the past few decades, the cesarean section (CS) delivery rate has been increasing almost everywhere, and the Arab region is no exception. Although the actual risks of death from CS are decreasing in the western world, data extrapolated from confidential enquiries in the UK estimated the risk of maternal death from CS to be three times as great as that with vaginal delivery [1]. Previous studies also indicate greater levels of morbidity and infertility among women undergoing CS [2]. The Arab world shows a large discrepancy in their population-based CS rates, with some countries having exceptionally high CS rates and other very low rates. Such differences can be accounted largely by each country’s developmental level [3]. Although rates exceeding 15% are unnecessarily high, very low rates are also problematic as they may reflect lack of access to needed obstetric care in some low income countries. Thus, policies to reduce or increase CS deliveries have been suggested depending on the context in question.

Information on rates of CS is not easily obtained for most Arab countries because of lack of good national registration systems. Prevalence estimates of hospital-based CS in 18 Arab countries are available from reports based on nationally representative surveys and small-scale facility-based studies. The purpose of this paper is to review this available evidence and describe levels and trends of CS delivery in countries for which data are available. Specifically, the paper aims to document and examine the most recent estimates of CS delivery across countries, and describe country-specific trends. In addition, the paper intends to examine within-country variations in CS delivery by selected socio-economic characteristics of respondents.

Materials and methods

For this review, we relied on hospital-based estimates of CS as these capture more accurately the prevalence of this procedure. The national-level estimates are largely drawn from reports of the PAPCHILD of the League of Arab States and UNFPA, the Gulf Family Health Survey and Demographic and Health Survey programs. These survey programs use similar data collection and estimation methods, with national surveys based on standardized instruments and representative samples, thus enhancing comparability of estimates among countries and over time. Neither the PAPCHILD nor DHS provide data for the Palestinian occupied areas. As such, we relied on data from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, an annual published report on the health status of Palestinians published by the Palestinian Ministry of Health. All these national surveys provided information on pregnancy and childbirth aspects, as well as on issues relating to antenatal and postnatal care. Specifically, mothers were asked if they had any pregnancy during the 5-year preceding the survey, and about complications during delivery if any.

Our review of available survey-based evidence proceeded as follows. First, micro-data from the DHS program were used for Egypt (EDHS 2000), Yemen (YDHS 1997) and Mauritania (ORC Macro, 2003). For Jordan (JDHS 1997), we used data from the published report. For the Palestinian territories, the 1996 Demographic Survey in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, designed and implemented by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, was used to calculate estimates for the Palestinian areas. The Palestinian analysis is split by region because of the large differences between West Bank and Gaza Strip. Finally, data for the remaining counties were obtained from published reports of national surveys carried out by PAPCHILD of the League of Arab States and UNFPA. Published reports from the Arab Maternal and Child Health Survey program were used for Algeria (AMCHS 1993), Lebanon (LMCHS 1996), Libya (ALMCHS 1995), Morocco (MMCHS 1999), Sudan (SMCHS 1993), and Tunisia (TMCHS 1994-5), countries where national micro-data could not be accessed. Likewise, the Gulf Family Health Survey reports were used for information about Bahrain (BFHS 1995), Kuwait (KFHS 1996), Oman (OFHS 1995), Qatar (QFHS 1998), Saudi Arabia (SAFHS 1996), and UAE (EFHS 1995).

In addition, published studies were reviewed for recent hospital-based estimates from data collected in facilities. A Medline/PUBMED search was made for all studies on CS done between 1980 and 2005 in hospitals of any country in the Arab region. The following terms were used for this purpose: “caesarean section/Arab*”, “caesarean/trends”, and “caesarean section/statistics and numerical data”. Eligible studies included those with hospital-based samples. We excluded studies reporting estimates based on interventions or high risk populations such as breech cases, diabetic patients, etc.

For the analysis, we first estimated or documented hospital caesarean section rates for the countries under examination. For all national estimates reported here, confidence intervals were calculated to assess the significance of the differences in the estimated rates. Bivariate analyses with selected socio-economic indicators was undertaken to better understand the differentials in CS rates for selected countries in the Arab region. We confined this analysis to mother’s age, education and place of residence owing to the availability of data, particularly in countries where micro-data could not be accessed.

Results

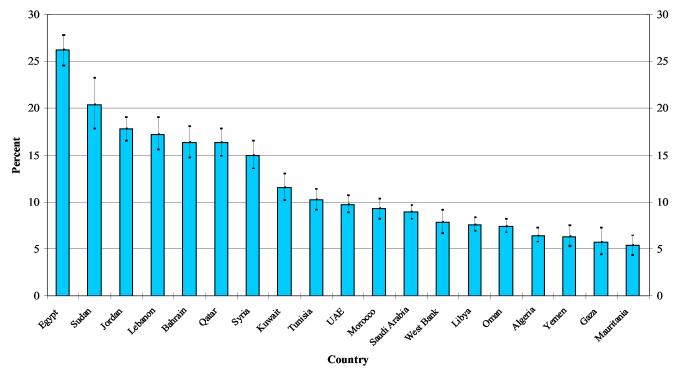

Figure 1 summarizes the most recent hospital-based CS rates based on national-level household surveys. There is a large variation in the CS rates found across countries, with Egypt having the highest CS rate at 26.2% and Mauritania the lowest at 5.3%. Six countries (Egypt, Sudan, Jordan, Lebanon, Bahrain, and Qatar) had CS rates exceeding the WHO threshold of 15%, with the remaining 13 countries having caesarean rates ranging between 5-15%. Syria, Kuwait and Tunisia have CS rates that range between 10% and 15%. UAE, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, West Bank, Libya and Oman have CS rates that range between 7% and 9%. Finally, Algeria, Yemen, Gaza and Mauritania had the lowest rates, 5%-6%.

Figure 1.

Hospital based caesarean section rates in selected Arab countries

Rates of CS from 17 hospital-based studies were available for Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and UAE (Table 1). Nine of these studies were conducted in Saudi Arabia and five in Jordan. Most of these studies (9 of 12) were based on samples from a single hospital. Results from the hospital-based studies often were different than those produced by national household surveys. In Jordan, a study estimated a CS rate of 7.7% during the period between 1991 and 1997 [10], compared to a rate of almost 13% in the 1997 Jordan Demographic Health Survey [6]. However, a hospital-based study conducted in 1990-1992 [8] produced a very similar rate, 8.0% to the 1990 Jordan Demographic Health Survey estimate of 8.5% [6]. In the case of Saudi Arabia, whereas a study [27] reported a CS rate ranging between 12-13% for the years 1996-97, based on a different facility but for the 1992-96 period, another study [31] documented a CS prevalence rate of around 9.5%. Two other studies implemented in two different hospitals during 1994 calculated slightly different CS rates, 9.9% and 11.5%l respectively [29, 30]. All the hospital based studies, including one conducted in 1984, report rates higher than the estimate of 8.9% published by the 1996 Saudi Arabia Family Health Survey [28]. In UAE, a hospital based study show a CS rate of 6.9% in 1994, which is lower than the national survey estimate of 9.7 in 1995. The hospital based studies in Kuwait and Lebanon show slightly different CS rates than the national survey estimates. However, these rates are not strictly comparable because they were conducted in different time periods.

Table 1.

Published hospital-based caesarean section rate in selected Arab countries

| Country | Hospital-based caesarean section | Year | Survey | Scope | Source [reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 6.4 | 1993 | AMCHS | National | Algeria Maternal and Child Health Survey (1994) [4] |

| Bahrain | 16.3 | 1995 | BFHS | National | Bahrain Family Health Survey (1995) [5] |

| Egypt | |||||

| 1 | 26.2 | 2003 | EDHS | National | Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (2003) [6] |

| 2 | 20.9 | 2000 | EDHS | National | Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (2000) [6] |

| 4 | 22.0 | 1999-2000 | [7] | ||

| 3 | 18.5 | 1995 | EDHS | National | Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (1995) [6] |

| 4 | 15.3 | 1992 | EDHS | National | Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (1992) [6] |

| 5 | 13.9 | 1987-1988 | [7] | ||

| Jordan | |||||

| 1 | 17.8 | 2002 | JDHS | National | Jordan Demographic and Health Survey (2002) [6] |

| 2 | 10.9 | 1999-2001 | 7 hospitals | [8] | |

| 2 | 12.9 | 1997 | JDHS | National | Jordan Demographic and Health Survey (1997) [6] |

| 3 | 8.8 | 1995 | 1 hospital | [9] | |

| 3 | 8.5 | 1990 | JDHS | National | Jordan Demographic and Health Survey (1990) [6] |

| 3 | 8.0 | 1990-1992 | 7 hospitals | [8] | |

| 4 | 7.7 | 1991-97 | 1 hospital | [10] | |

| 5 | 8.7-15.5 | 1987-1993 | 1 hospital | [11] | |

| Kuwait | |||||

| 1 | 11.5 | 1996 | KFHS | National | Kuwait Family Health Survey (1996) [12] |

| 2 | 9.4 | 1983-88 | [13] | ||

| Lebanon | |||||

| 1 | 18.0 | 2000 | National sample of randomized 39 hospitals | [14] | |

| 2 | 17.2 | 1995-96 | LMCHS | National | Lebanon Maternal and Child Health Survey (1996) [15] |

| Libya | 7.6 | 1995 | ALMCHS | National | Arab Libyan Maternal and Child Health Survey (1996) [16] |

| Mauritania | |||||

| 1 | 6.6 | 2000-1 | MDHS | National | Mauritania Demographic and Health Survey (2001) [6] |

| 2 | 5.2 | 1990-1 | MMCHS | National | Mauritania Maternal and Child Health Survey (1992) [17] |

| Morocco | |||||

| 1 | 9.3 | 2003-2004 | MDHS | National | Morocco Demographic and Health Survey (2004) [6] |

| 2 | 15.3 | 1999 | MMCHS | National | Morocco Maternal and Child Health Survey [18] |

| 3 | 8.0 | 1995 | MDHS | National | Morocco Demographic and Health Survey (1995) [6] |

| 4 | 6.8 | 1992 | MDHS | National | Morocco Demographic and Health Survey (1992) [6] |

| Oman | 7.4 | 1995 | OFHS | National | Oman Family Health Survey (1995) [19] |

| Palestine | 7.0 | 1996 | PDS | Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (1997) [20] | |

| West Bank | |||||

| 1 | 15.7 | 2003 | MOH-PHIC | MOH hospitals | Health Status in Palestine (2004) [21] |

| 2 | 7.8 | 1996 | PDS | Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (1997) [20] | |

| Gaza | |||||

| 1 | 14.4 | 2003 | MOH-PHIC | MOH hospitals | Health Status in Palestine (2004) [21] |

| 2 | 5.7 | 1996 | PDS | Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (1997) [20] | |

| Qatar | 16.3 | 1998 | QFHS | National | Qatar Family Health Survey (1998) [22] |

| Sudan | 20.4 | 1993 | SMCHS | National | Sudan Maternal and Child Health Survey (1995) [23] |

| Tunisia | 10.2 | 1994-95 | TMCHS | National | Tunisia Maternal and Child Health Survey (1996) [24] |

| Saudi Arabia | |||||

| 1 | 13.0 | 2002 | 6 primary health care centers | [25] | |

| 2 | 19.4 (NPG)(1); 18.3 (GMPG)(1) | 1997-99 | 1 hospital | [26] | |

| 3 | 12.0 - 13.0 | 1996-97 | 1 hospital | [27] | |

| 4 | 8.9 | 1996 | SAFHS | Saudi Arabia Family Health Survey (1996) [28] | |

| 5 | 9.9 | 1994 | [29] | ||

| 6 | 11.5-13.4 | 1994-99 | 1 hospital | [30] | |

| 7 | 9.5 | 1992-96 | 1 hospital | [31] | |

| 8 | 10.3 | 1989-93 | 1 hospital | [32] | |

| 9 | 9.9 | 1984 | [33] | ||

| Syria | |||||

| 1 | 15.0 | 2002 | SFHS | National | Syrian Family Health Survey (2002) [37] |

| 2 | 12.0 | 1993 | SMCHS | National | Syrian Maternal and Child Health Survey (1995) [38] |

| UAE | |||||

| 1 | 9.3 (non-obese); 15.2 (obese) | 1996-8 | 1 hospital | [34] | |

| 2 | 9.7 | 1995 | EFHS | National | United Arab Emirates family health survey (1995) [35] |

| 3 | 6.9 | 1994 | [36] | ||

| Yemen | |||||

| 1 | 6.3 | 1997 | YDHS | National | Yemen Demographic and Health Survey (1997) [6] |

| 2 | 11.2 | 1991-92 | YDHS | National | Yemen Demographic and Health Survey (1992) [6] |

Note: *NPG (Nulliparous women), and GMPG (grandmultiparous women)

There has been an increasing trend of CS delivery across countries in the region (Table 1). The CS rate in Jordan increased from 7.7% in 1991 to 17.8% in 2002. In Egypt, there was also a sharp increase in the CS rate from a 15.3% in 1992 to 26.2% in 2003. During the period between 1992 and 2003-2004, Moroccan CS rates show a slower increase from 6.8% to 9.3%. Within almost the same time period, the CS rates in Syria increased from 12% in 1993 to 15% in 2002. Similarly, CS rates increased in Saudi Arabia from 9.9% in 1984 to 13.0% in 2002. Finally, in Lebanon the CS rate increased slightly from 17.2% in 1995 to 18% in 2000.

Table 2 reports associations between CS deliveries and selected background characteristics of respondents. Positive associations are found between CS rates and mother’s age, education, and place of residence. Overall, older women have higher rates of CS than younger women. Interestingly, the disparity in CS rates between older and younger women exceeds 5% in six settings: Egypt, Kuwait, Lebanon, Qatar, Syria, West Bank and Bahrain. In Kuwait, for example, the CS rate among women aged 35 years and above is 17.3% compared to only 4.8% among women aged 15-35 years. Smaller percentage differences, 7-8%, between the two age groups are observed for Egypt, Lebanon, Qatar, Syria and West Bank. However, three countries (Algeria, Sudan and UAE) have CS rates higher at younger ages than older ages. In Sudan, 25.2% of the women aged 15-34 have CS whereas 14.8% of those aged 35+ years age group have this surgical procedure.

Table 2.

Hospital-based caesarean section rates by age, education and residence in selected Arab countries

| Arab countries | Mother’s age | Mother’s education | Residence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15-34 | 35+ | Below secondary | Secondary+ | Rural | Urban | |

| Algeria | 6.8 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 10.0 | 5.7 | 6.9 |

| Bahrain | 15.2 | 17.8 | 17.0 | 17.9 | - | - |

| Egypt | 20.1 | 28.0 | 18.0 | 23.6 | 17.4 | 23.7 |

| Gaza | 4.2 | 9.6 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 6.6 |

| Jordan | 5.8 | 10.7 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 7.3 |

| Kuwait | 4.8 | 17.3 | 9.9 | 12.1 | - | - |

| Lebanon | 14.5 | 21.2 | 14.9 | 20.1 | - | - |

| Mauritania | - | - | 2.4 | 9.4 | 0.5 | 4.2 |

| Morocco | 7.0 | 10.6 | 6.4 | 12.0 | 5.7 | 9.2 |

| Oman | 6.2 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 11.5 | 4.9 | 7.7 |

| Qatar | 13.9 | 21.4 | 14.7 | 16.5 | - | - |

| Saudi Arabia | 5.8 | 11.0 | 8.1 | 10.5 | 5.2 | 9.4 |

| Sudan | 25.2 | 14.8 | 18.9 | 22.9 | 24.4 | 18.6 |

| Syria | 10.3 | 17.6 | 11.9 | 15.4 | 11.7 | 12.8 |

| UAE | 12.5 | 11.9 | 9.7 | 10.7 | 8.0 | 10.5 |

| West Bank | 5.9 | 14.1 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 8.5 |

| Yemen | 6.0 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 3.0 | 6.3 | 6.2 |

In general highly educated women are more likely to undergo this surgery than their less educated counterparts (Table 2). The discrepancies are not that large, with the highest ranging between 5 and 6% in 5 out of the 17 countries. In Lebanon, for example, the CS rate among the less educated (below secondary level) is 14.9% as compared to 20.1% among the more educated women. Egypt has a similar percentage difference, but at higher rates for both groups (18% versus 23.6%). On the other hand, Jordan, West Bank and Yemen show the opposite pattern, with rates of CS being relatively higher among less educated women than the more educated. However, the educational differentials in the CS rates in these three countries are rather small, with Yemen having the largest percentage difference of 3.4%.

Likewise, the discrepancies in CS rates by rural-urban residences are relatively small, with no country exceeding 5%. The highest rural-urban differentials in the CS rates are in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan, amounting to 4-5% percent point differences. CS rates are higher among women living in urban areas than rural areas in all the countries, except Sudan and Yemen.

Discussion

This brief review revealed great disparities in the hospital-based CS rates across and within countries in the Arab region. The discrepancies may reflect differential accessibility to maternal health services where the rates are low, or to the misuse of medical technology in performing this surgical procedure in countries where the rates of CS at the hospital level are high. Results based on facility-based studies were not always consistent with nationally-based surveys, perhaps due to the selectivity of the hospitals used in the small-scale studies. Trends in CS rates in countries where data were available at the national-level for more than one time period generally showed increased use of this procedure, and a doubling within a decade in countries like Egypt and Jordan. Such increases in the CS rates were not accompanied by consistent declines in the maternal mortality ratios during the past few decades. This may reflect the fact that women undergoing CS are not necessarily the ones who need them most.

Geographically, the disparities in the CS rate were evident within and across the three geographic regions of North Africa, Levant, and Gulf countries. Particularly, high discrepancies were found among North African countries, with low rates in Algeria and Mauritania and high levels in Sudan and Egypt. The majority of the Gulf countries had CS rates below 15%, except for Bahrain and Qatar, with rates of about 16% respectively. As for the Levant countries, the CS rates ranged from 14% in Gaza to 18% in Lebanon.

Thus, the reported rates do not seem to correspond with the countries’ levels of socio-economic development. [3] Egypt was found to exhibit higher rates of CS than several other Arab countries with better socio-economic profiles like Qatar, Bahrain and UAE. [3] Similarly, middle-income countries like Syria, Jordan and Lebanon were found to have CS rates close to high-income counties such as Qatar or Bahrain. [3]

Within-countries, CS rates varied with non-medical risk factors such as age, education and rural-urban residence. Specifically, women with secondary level of education, living in urban places, and over 35 years of age were more likely to undergo CS deliveries than other women. The largest discrepancies in the CS rates were found by age. The positive association between CS delivery and maternal age is supported by other studies [39, 40, 41, 42], and might be attributed to higher risks of complications as the age of the mother increases. Various studies found higher rates of labor fetal distress and failure to advance at the time of delivery among older mothers, all factors highly associated with CS delivery [40, 43]. However, higher rates of CS among older women cannot entirely be explained by their tendency towards more complicated pregnancies and births [41]. In some situations, maternal preferences, perceived potential for complications by medical doctors, as well as convenience of delivery may also be important determinants of CS delivery [41].

However, in a few settings where teenage pregnancies are common, the CS rates were higher at younger ages. The case of Sudan is particularly alarming, with a difference in CS of more than 10% between younger and older women. We cannot determine the precise reasons for this finding with the data at hand, but the observed rates could be due to the relatively high proportions of teenage pregnancies in this country.

Urban residents generally reported higher rates of CS than their rural counterparts. This finding is expected given the urban advantage in accessibility to better health care services and availability of skilled birth attendants, making it possible to detect complications that may require caesarean delivery [40, 42, 44].

With a few exceptions, our findings show that women with secondary education have higher rates of CS than women with lower education. These findings are consistent with previous studies, and may reflect the tendency of educated women to seek care in health institutions [40]. A study in Northern Thailand found that Thai women with social resources have more control over the experience of childbirth than other women [45]. It is doubtful if women in the Arab context have much of a choice over their mode of deliveries [14, 46, 47], with the observed disparities reflecting perhaps differential access to health care.

This review has several limitations. First, the review relied mainly on published reports and aggregated data because the necessary micro-data from the PAPCHILD and similar surveys in the region are not available to researchers (save the Arab League and UNFPA staff) despite the large costs in fielding such surveys. Second, national level data were available for only one year for most countries in the region. Third, although reports from the majority of available surveys contain results for common risk factors, indicators of medical complications were rarely available. Fourth, the questions concerning CS delivery in national level surveys such as the DHS or PAPCHILD have never been validated, and our review therefore excluded items concerning medical indications of CS delivery. Fifth, although rates reported by nationally representative sample surveys may reflect true rates in the population, it was not possible to assess the bias and/or accuracy of facility-based studies. Finally, our review was confined to the English language studies, thus excluding regional studies and findings written in Arabic.

Conclusions

This review shows large discrepancies in the CS rates despite an overall increasing trend in CS delivery. High rates of CS deliveries, exceeding the 15% WHO threshold [48], in low and middle income countries is of policy concern because of the medical effects and the high costs of undergoing operative deliveries. There is therefore a need to address the factors that increase the risk of operative deliveries in this part of the world in order to reduce the practice. Here, emphasis should perhaps be placed on prevention involving individual behavioral aspects, with regard to decision making, of both the physician and the patient [40]. On the other hand, very low rates below the minimum 5% specified by WHO, were observed for some vulnerable, or otherwise disadvantaged, groups of women in various countries. Here, increasing access to adequate health care facilities for rural, less educated and younger women should be emphasized. Clearly, more in-depth research is needed in order to identify the individual risk factors involved, perhaps with an interdisciplinary approach encompassing social science and medical fields to better identify the challenges facing both the patients and medical professionals in controlling this practice [49]. In addition, there are many country-specific factors that need to be taken into account in interpreting the data observed. Future studies should consider the importance of country-specific factors such as access to health care, care seeking behavior, availability of staff and infrastructure, medical technology, and quality and continuity of care.

References

- 1.Hall HM, Bewley S. Maternal mortality and mode of delivery. The Lancet. 1999;354:776. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)76016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gass CW. It is the right of every anaesthetist to refuse to participate in a maternal-request caesarean section. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2006;15:33–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurdi R, Khawaja M. Caesarean section rates in the Arab region: a cross-national study. Health Policy and Planning. 2004;19:101–110. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health and Population [Algeria] Algeria Maternal and Child Health survey: principal report. The Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naseeb T, Farid SM. Bahrain Family Health Survey 2000. Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey; [Google Scholar]

- 6.ORC Macro. Demographic and Health Surveys. Calverton, USA: Measure DHS +STAT compiler. Macro International Inc.; 2003. [accessed in July 2003]. Web site: http://www.measuredhs.com/, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khawaja M, Jurdi R, Kabakian-Kasholian T. Rising trends in cesarean section rates in Egypt. Birth. 2004;31:12–16. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.0269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindawi IM, Meri ZB. The Jordanian cesarean section rate. Saudi Medicine Journal. 2004;25:1631–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Heija AT, Jallad MF, Abukteish F. Obstetrics and perinatal outcome of pregnancies after the age of 45. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;19:486–8. doi: 10.1080/01443619964265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akasheh HF, Amarin V. Caesarean sections at Queen Alia Military Hospital, Jordan: a six-year review. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2000;6:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziadeh SM, Sunna EI. Decreased cesarean birth rates and improved perinatal outcome: a seven-year study. BIRTH. 1995;22:144–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1995.tb00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alnesef Y, Al-Rashoud R, Farid SM. Kuwait Family Health Survey. Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guirguis W, Al-Saleh K. Caesarean section in Kuwait, 1983 through 1988. Journal of Egypt Public Health Association. 1991;66:451–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khayat R, Campbell O. Hospital practices in maternity wards in Lebanon. Health Policy and Planning. 2000;15:270–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Public Health [Lebanon] Lebanon Maternal and Child Health Survey: principal report. Republic of Lebanon and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The General People’s Committee for Health and Social Insurance [Libya] Arab Libyan Maternal and Child Health Survey: principal report. The Great Socialist; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Statistical Office [Mauritania] Mauritania Maternal and Child Health Survey: principal report. The Republic of Mauritania and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health [Morocco] Moroccan Maternal and Child Health Survey: principal report. The Republic of Morocco and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sulaiman AJ, Al-Riyami A, Farid SM. Oman Family Health Survey. Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics . Health Survey in the West Bank and Gazastrip-1996. Main findings. Ramallah; Palestine: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health, Palestinian Health Information Center (MOH-PHIC) Health Status in Palestine 2003: Hospitals. 2004. Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Jaber KA, Farid SM. Qatar Family Health Survey. Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Public Health [Sudan] Sudan Maternal and Child Health Survey: principal report. Republic of Sudan and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Public Health [Tunisia] Tunisia Maternal and Child Health Survey: summary report. Republic of Tunisia and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shawky S, Abalkhail BA. Maternal factors associated with the duration of breast feeding in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Paediatric & Perinatal Epidemiology. 2003;17:91–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobande AA, Archibong EI, Eskandar M. Primary caesarean section in nulliparous and grandmultiparous Saudi women from the Abha region: indications and outcomes. West African Journal of Medicine. 2003;22:232–235. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i3.27956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesleh RA, Asiri F, Al-Naim M. Caesarean section in the primigravid. Saudi Medical Journal. 2000;21:957–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoja TA, Farid SM. Saudi Arabia Family Health Survey. Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elhag BI, Milaat WA, Taylouni ER. An audit of caesarean section among Saudi females in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association. 1994;69:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mesleh RA, Al Naim M, Krimly A. Pregnancy outcomes of patients with previous four or more caesarean sections. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;21:355–7. doi: 10.1080/01443610120059879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onuora VC, et al. Major injuries to the urinary tract in association with childbirth. East African Medical Journal. 1997;74(8):523–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soltan MH, Khashoggi T, Adelusi B. Pregnancy following rupture of the pregnant uterus. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 1996;52:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(95)02560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chattopadhyay SK, et al. Cesarean section; changing patterns in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 1987;25:387–394. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(87)90345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumari AS. Pregnancy outcome in women with morbid obesity. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2001;73:101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fikri M, Farid SM. United Arab Emirates Family Health Survey. Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes PF, Morrison J. Pregnancy outcome data in a UAE population: what can they tell us? Asia Oceania Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;20:183–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1994.tb00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Central bureau of Statistics [Syria] Family Health Survey in the Syrian Arab Republic: summary report. Syrian Arab Republic and the Pan Arab Project for Family Health (PAPFAM) of the League of Arab Sates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Central bureau of Statistics [Syria] Syrian Maternal and Child Health Survey: principal report. The Republic of Syria and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khawaja M, Kabakian-Kasholian T, Jurdi R. Determinants of caesarean section in Egypt: evidence from the demographic and health survey. Health Policy. 2004;69:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Padmadas SS, et al. Caesarean section delivery in Kerala, India: evidence from a National Family Health Survey. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:511–21. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bell JS, et al. Do obstetric complications explain high caesarean section rates among women over 30? A retrospective analysis. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:894–895. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7291.894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webster LA, et al. Prevalence and determinants of caesarean section in Jamaica. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1992;24(4):515–25. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000020071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenthal AN, Paterson-Brown S. Is there an incremental rise in the risk of obstetric intervention with increasing maternal age? British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;105:1064–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ondimu KN. Levels and risk factors of operative deliveries in four health facilities in Kisumu District, Kenya. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;20(5):486–91. doi: 10.1080/014436100434668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liamputtong P. Birth and social class: Northern Thai women’s lived experiences of caesarean and vaginal birth. Sociology of Health and illness. 2005;27:243–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bashour H. Syrian women’s preferences for birth attendant and birth place. Birth. 2005;32:20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kabakian-Khasholian T, et al. Women’s experiences of maternity care: Satisfaction or passivity? Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:103. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00443-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 326(8,4520):436–400. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tatar, et al. Women’s perceptions of caesarean section: reflections from a Turkish teaching hospital. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50:1227–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]