Abstract

Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) catalyzes the first enzymatic step in the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids 14 to 20 carbons in length. More than 100 cases of VLCAD deficiency have been reported with the disease varying from a severe, often fatal neonatal form to a mild adult-onset form. VLCAD is distinguished from matrix-soluble acyl-CoA dehydrogenases by its unique C-terminal domain, homodimeric structure, and localization to the inner mitochondrial membrane. We have for the first time expressed and purified VLCAD using a bacterial system. Recombinant VLCAD had similar biochemical properties to those reported for native VLCAD and the bacterial system was used to study six previously described disease-causing missense mutations including the two most common mild mutations (T220M, V243A), a mutation leading to the severe disease phenotype (R429W), and three mutations in the C-terminal domain (A450P, L462P, and R573W). Of particular interest was the finding that the A450P and L462P bacterial extracts had normal or increased amounts of VLCAD antigen and activity. In the pure form L462P had roughly 30% of wild type activity while A450P was normal. Using computer modeling both mutations were mapped to a predicted charged surface of VLCAD that we postulate interacts with the mitochondrial membrane. In a membrane pull down assay both mutants showed greatly reduced mitochondrial membrane association, suggesting a mechanism for the disease in these patients. In summary, the bacterial expression system developed here will significantly advance our understanding of both the clinical aspects of VLCAD deficiency and the basic biochemistry of the enzyme.

INTRODUCTION

Very-long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) plays a key role in the mitochondrial oxidation of fatty acids. VLCAD is a member of the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACD) enzyme family which currently has eleven known members. The ACDs catalyze the rate-limiting step in the mitochondrial β-oxidation of activated fatty acids and branched-chain amino acids. Each possesses a characteristic pattern of substrate utilization but these partially overlap for some enzymes. Clinical disease results from genetic deficiencies of the ACD family [1–4]. VLCAD appears to be the major ACD responsible for the catalysis of acyl-CoAs 16 to 20 carbons in length in human liver, heart, and muscle. VLCAD deficiency has severe metabolic consequences for these organs. More than 100 cases of VLCAD deficiency have been documented in the literature with three different disease phenotypes [1, 5]. A severe infant-onset form is characterized by acute metabolic decompensation with hypoketotic hypoglycemia, dicarboxylic aciduria, liver dysfunction, and cardiomyopathy. A second form of the disease presents later in infancy or childhood but has a milder phenotype without cardiac involvement. The third form is of adolescent or adult onset and is dominated by muscle dysfunction that is often exercise-induced [6, 7]. A genotype-phenotype correlation has been proposed by Andresen et al [5] who surveyed the clinical phenotype in 55 unrelated VLCAD deficient patients with known mutations. Not surprisingly, children with the severe phenotype tended to have null mutations (71% of identified alleles in these patients) while patients with the two milder forms of the disease were more likely to have missense mutations (82% and 93% of identified alleles for the milder childhood form and the adult form, respectively). Nevertheless, a few missense mutations were clearly associated with the severe phenotype. Although these data suggested that missense mutations in VLCAD might obviate clinical symptoms due to some degree of residual activity, no correlation was seen between the mutations identified and residual VLCAD activity in fibroblasts. Moreover, the functional effects of only a few of the known VLCAD missense mutations have been directly characterized.

We have previously used prokaryotic expression systems to express, purify, and characterize the biochemical properties of ACD enzymes [8–12]. Several of these have been crystallized and studied by X-ray diffraction yielding informative three-dimensional models. The study of VLCAD, however, has been limited due to difficulties with prokaryotic expression. These difficulties may be related in part to physical properties that distinguish the VLCAD enzyme from other ACD family members. Most of the ACDs share a common homotetrameric “dimer of dimers” structure and localize to the mitochondrial matrix. The monomer size for the homotetrameric ACDs is roughly 45 kDa. In contrast, VLCAD monomers are nearly 70 kDa due to an extended 180 amino acid C-terminal domain, and VLCAD forms homodimers rather than tetramers. Additionally, VLCAD is associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane, an interaction that has long been postulated without proof to be mediated by the C-terminus [13, 14].

Recently, we expressed and purified a new ACD family member ACAD9 using an E coli expression system [8]. The ACAD9 amino acid sequence is 47% identical and 65% similar to VLCAD. We showed it also to be a homodimer with an extended C-terminal domain that localizes to the inner mitochondrial membrane. Expression of ACAD9 in the novel C43 (DE3) strain of E coli [15] suggested that use of this strain might also be successful for VLCAD, but the previously recognized full-length VLCAD coding sequence (GenBank NM_000018) failed to produce VLCAD protein using conditions optimized for ACAD9. Interestingly, an N-terminally truncated variant of VLCAD was recently posted in GenBank (NM_001033859) that lacks exon 3 due to alternative splicing (ΔEx3). This ΔEx3 VLCAD variant is missing 22 amino acids (residues 7 to 28 of the mature sequence) resulting in an amino terminus that more closely resembles that of ACAD9 (Figure 1a). Hypothesizing that the ACAD9-like amino terminus may improve prokaryotic expression, we introduced the ΔEx3 VLCAD sequence into the C43(DE3) expression strain. Indeed, expression levels of the ΔEx3 variant were sufficient for VLCAD purification. We then used the expression system to study six missense mutations previously described in VLCAD deficient patients (T220M, V243A, R429W, A450P, L462P, and R573W). T220M and V243A are the most frequently reported missense mutations in VLCAD deficient patients [5]. R429W and R573W are among the missense mutations believed to result in the severe clinical phenotype [5]. A450P and L462P are located in the C-terminal domain unique to VLCAD and ACAD9. Characterization of purified wild type, A450P, and L462P VLCAD proteins confirmed the long-held assumption that the C-terminus plays a key role in mitochondrial membrane association. The prokaryotic system developed here will facilitate investigation of VLCAD structure-function.

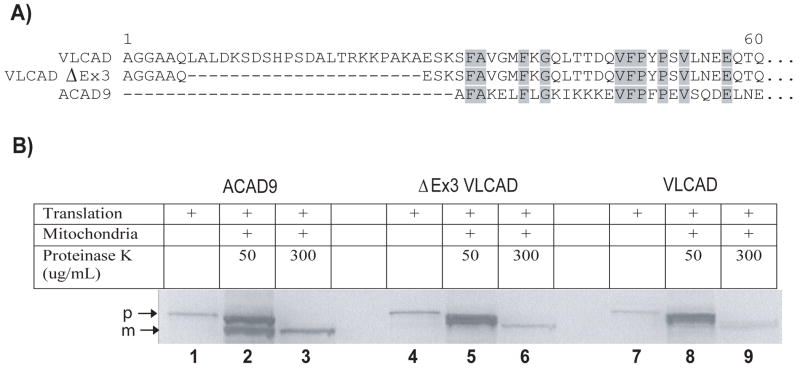

Figure 1.

The ΔEx3 VLCAD variant imports correctly into mitochondria. (A) Alignment of the full-length VLCAD, ΔEx3 VLCAD, and ACAD9 mature amino terminal sequences. (B) In vitro transcribed/translated precursor forms of ACAD9, ΔEx3 VLCAD, and VLCAD (loaded as controls into lanes 1, 4, and 7, respectively) were incubated with intact rat liver mitochondria for 45 min and then digested with proteinase K for 30 min to remove any remaining unimported precursor. Any imported protein will be protected from the protease and will be smaller in size due to processing of the mitochondrial leader sequence. Lanes 2, 5, and 8 show a mixture of remnant precursor (p) and protected mature (m) proteins following partial protease digestion (50 μg/ml proteinase K for 30 minutes) while in lanes 3, 6, and 9 only the protected, imported mature proteins remain following a full protease digestion (300 μg/ml proteinase K for 30 minutes).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of VLCAD ΔEx3 expression vector

The full-length human precursor VLCAD sequence in vector pcDNA3.1 was a kind gift of Dr. Brage Andresen. PCR-based mutagenesis was used to delete exon 3 yielding the mitochondrial precursor form of ΔEx3 in pcDNA3.1. Full-length mature VLCAD and mature VLCAD ΔEx3 constructs for prokaryotic expression were created by PCR amplification using the corresponding pcDNA3.1 precursor plasmids as template. The 5′ primers were designed to introduce a translation initiation codon just before the mature N-terminal amino acid as well as an NdeI restriction site. The 3′-primers consisted of the last 20 nucleotides of the coding sequence, including the termination codon, followed by an EcoRI restriction site. The resulting amplified VLCAD PCR products were subcloned into the NdeI and EcoRI sites of the pET-21a (+) prokaryotic expression vector (Novagen, Madison, WI).

In vitro mitochondrial import

VLCAD and ACAD9 precursor proteins were synthesized from 1 μg of plasmid DNA (pcDNA3.1 containing the various cDNAs) by coupled in vitro transcription/translation in the presence of 35S-labeled methionine (20 μCi, 1250 Ci/mmol). Liver mitochondria were freshly prepared from young male Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously [16, 17]. The final pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of HMS buffer (5 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 220 mM D-mannitol, and 70 mM sucrose) and diluted to a final concentration of 20 mg/ml protein. For mitochondrial import, 35 μl of translation mixture containing the 35S-labeled precursor proteins were mixed with 85 μl of the mitochondrial suspension and 30 μl of HMS buffer to a total volume of 150 μl and incubated at 30 °C for 45 min. The mitochondria were then pelleted by centrifugation at 9100 × g for 2 min at 4 °C and gently resuspended in 180 μl of HMS buffer. Either 50 μg/ml or 300 μg/ml proteinase K was added and a 30 minute digestion was carried out on ice to remove residual 35S-labeled precursor protein associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane. During the digestion any imported and processed 35S-labeled VLCAD is protected from the proteinase K which cannot enter the intact mitochondria. The mitochondria were pelleted as before and washed twice in cold HMS buffer containing 1 mM PMSF. After the final wash the mitochondria were solubilized in 30 μl of SDS-PAGE loading buffer, boiled for 10 min, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Gels were transferred to supported nitrocellulose and exposed to X-ray film overnight.

Introduction of patient mutations into VLCAD ΔEx3

Six previously reported VLCAD patient mutations were chosen for introduction into the VLCAD ΔEx3 pET-21 expression construct. These were 779C>T, 848T>C, 1405C>T, 1468G>C, 1505T>C, and 1837C>T, corresponding to amino acid substitutions T220M, V243A, R429W, A450P, L462P, and R573W, respectively (mature sequence numbering) [5, 18]. The six single point mutations were introduced into the ΔEx3 VLCAD plasmid via mutagenic PCR primers using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Mutations were verified by sequencing and the plasmids were introduced into an E coli expression strain as detailed below.

Expression and purification of recombinant VLCADs

The pET-21a(+) expression constructs containing the various VLCAD sequences were transformed into the E. coli host strain C43 (DE3) (Avidis, Saint Beauzire, France). For small-scale expression 20 ml cultures were grown to mid-log phase (absorbance of 0.8–1.0 at 550 nm) at 37°C and induced overnight at 37°C by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were harvested and lysed by sonication on ice followed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 30 min. Supernatants were used to test enzyme activity and for western blotting as described below. Wildtype ΔEx3 VLCAD and the mutants A450P and L462P were also expressed in large-scale cultures (10 liters) for purification by fast protein liquid chromatography. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 200 mM KPO4 buffer supplemented with Complete™ protease inhibitor tablets (Roche, Manheim, Germany), 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, and sonicated on ice four times for 30 seconds at 10 minute intervals. The mixture was centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 40 min. The supernatant was precipitated with 55% ammonium sulfate and re-centrifuged. The precipitate was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 1mM EDTA, 1mM DDT, 0.1% soybean lecithin, and 0.2% Tween-20 and dialyzed against 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 0.2% Tween-20 overnight. Following dialysis dodecylmaltoside was added at a ratio of 0.3:1 (weight:volume) and the sample was subjected to chromatography on DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The elution gradient was 0 to 500 mM KPO4. Fractions with VLCAD activity were pooled, bound again to DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow, and eluted with a salt gradient (0 to 380 mM NaCl). Fractions with activity were again combined, dialyzed (25 mM KPO4, pH 6.3), and applied to an SP Sepharose Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Elution was achieved with a KPO4 gradient (pH 8.0). Tween-20 was added to all chromatography buffers (0.2%). Fractions containing VLCAD were concentrated, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. The molecular mass of the purified recombinant VLCAD proteins was estimated by gel filtration analysis using a BioSep SEC-S2000 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) in a Waters HPLC system (Milford, MA). The column was calibrated using standards purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ): ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), albumin (67 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and catalase (232 kDa).

Enzyme activity assays

Enzyme activity was measured with the anaerobic electron transfer flavoprotein (ETF) fluorescence reduction assay using an LS50B fluorescence spectrophotometer from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Wellesley, MA) with a heated cuvette block set to 32°C as described [12, 19]. Acyl-CoA substrates were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The reaction was started with the addition of the CoA ester substrate to give a final concentration of 25 μM. Activity was calculated with one milliunit of activity defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to completely reduce one nmol of ETF in one minute.

Mitochondrial membrane association assay

Membrane association was measured essentially following the method of Sumegi and Srere [20]. Rat liver mitochondria were isolated using differential centrifugation as previously described [8]. The final mitochondria pellet was resuspended in 0.6 ml of 50 mM KPO4, pH 7.0 and sonicated four times for 15 s. The suspension was centrifuged 15 min at 40,000 × g to separate the membranes from the mitochondrial matrix. The membrane pellet was washed four times in the same buffer by repeated resuspension and centrifugation. After four washes endogenous VLCAD activity was not detectable in the membrane pellet. Finally, the membranes were resuspended in the phosphate buffer and quantified spectrophotometrically by measuring protein content (A280 nm – A310 nm). For binding experiments, the specified amounts of membranes were incubated with 3 μg of pure VLCAD protein for 30 min on ice in a total volume of 50 μl of 50 mM KPO4, pH 7.0. The samples were then centrifuged 15 min at 40,000 × g and the supernatant carefully removed and saved. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of 50 mM KPO4, pH 7.0 and both fractions were immediately assayed for enzyme activity. The recovery of the added enzyme was calculated from the activities of the two fractions and the known specific activity of the added enzyme; recovery rates ranged from 85% to 95%. Data were expressed as the percentage of recovered activity appearing in the pellet versus the percent in the supernatant. Because 100% removal of the supernatant from the membrane pellet is not possible after centrifugation, the amount of supernatant trapped in the volume of the pellet was determined by substituting 35S-labeled methionine for the VLCAD protein in the reaction and performing scintillation counting on the supernatant and membrane pellets. The amount of radioactivity trapped in the pellet even at the largest amount of membranes used was negligible (< 5%).

Production of Anti-VLCAD Antiserum

Rabbit antiserum to purified VLCAD was raised by Cocalico Biologicals, Inc. (Reamstown, PA) according to standard company protocols. Rabbits were given an initial inoculation of 200 μg of purified protein and boosted four times with 200 μg of purified protein each at 1- or 2-week intervals. Reactivity of the final serum was confirmed by Western blotting.

Western blotting

Twenty-five micrograms of protein from E. coli crude cellular extracts were subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% Criterion SDS polyacrylamide gel (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Separated proteins were transferred to 0.2 μm Optitran™ nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) using a TE Series Transphore Electrophoresis Unit (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA). VLCAD antigen was detected using the rabbit anti-VLCAD polyclonal antibody at a 1:1000 dilution followed by a 1:3000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and visualization with a nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate color development solution according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioRad, Hercules, CA) as described previously (12).

Molecular modeling

Molecular modeling was performed on a Silicon Graphics Fuel workstation (Mountain View, CA) using the Insight II 2000 software package (Accelrys Technologies, San Diego, CA) and the published atomic coordinates of human isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase (1IVH), human isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (1RXO), porcine medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (3MDE), rat short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD, 1JQI), and M. elsdii butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase proteins [21–29]. The published protein models were superimposed by their secondary structure and collectively used as reference molecules. The FAD prosthetic group and acyl-CoA ligand were made part of the models as fixed molecules. Models were inspected manually for violations at the active site and other secondary structure deformations. Models with significant violations or secondary structure deformations were rejected and several models were further optimized using other Insight II modules and functions (23). Additionally, because of the homology between the C-terminus of VLCAD and the C-terminus of rat acyl-CoA oxidase (AOX), we used the atomic coordinates of the corresponding area of the latter (PDB code: 1IS2) as reference to build a model. Because of the low degree of homology between the two areas (12–28% depending on alignment algorithm used), amino acid sequence alignment was also refined manually in some areas.

RESULTS

Expression of VLCAD in E coli

Development of a prokaryotic expression system for VLCAD would provide a valuable tool for characterizing the functional effects of VLCAD point mutations identified in deficient patients. However, multiple previous attempts to accomplish this were unsuccessful in our hands. Because we had successfully used the mutant E. coli strain C43 (DE3) to express ACAD9 [8] we undertook similar experiments with VLCAD. However, the full-length human VLCAD cDNA cloned into the pET 21a+ expression vector and expressed in the C43 (DE3) host strain again failed to produce VLCAD antigen or activity. We then sought to express the ΔEx3 splice variant which lacks 22 amino acids just downstream of the mitochondrial leader peptide peptidase cleavage site (Figure 1a). When expressed in a cell-free transcription/translation system the ΔEx3 cDNA produced a VLCAD protein of predicted size that imported normally into rat liver mitochondria and was processed to the mature VLCAD protein (Figure 1b). We then inserted the mature ΔEx3 sequence into pET 21a+ and expressed it in the C43 (DE3) strain. VLCAD antigen and enzymatic activity were easily demonstrated in crude bacterial lysates expressing the ΔEx3 variant (Figure 2).

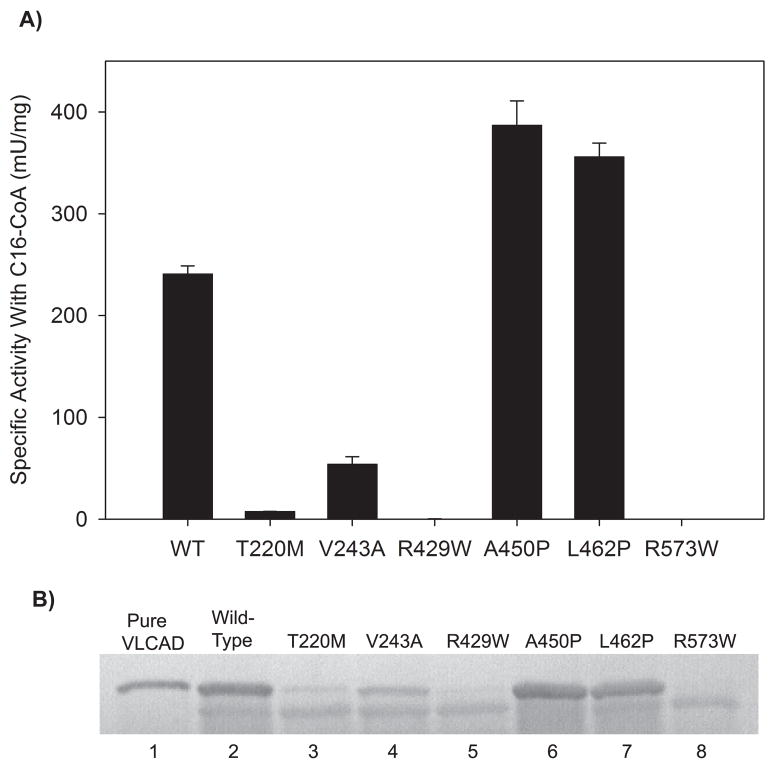

Figure 2.

Evaluation of enzyme activity and antigen in E coli crude lysates containing the recombinant VLCAD and various mutant VLCAD enzymes. (A) Activity was measured using C16:0-CoA as substrate. Bars represent means and standard deviations of triplicate assays. Note that mutant R429W had minimal detectable activity (0.4 ± 0.01 mU/mg) while R573W had no detectable activity. (B) VLCAD antigen was detected using a polyclonal antibody raised against the purified recombinant ΔEx3 VLCAD shown in lane 1. The top band represents VLCAD while the bottom band is due to non-specific immunoreactivity with an E coli protein. Lanes 2 through 8 contain 25 μg of E coli crude lysate from induced overnight C43 (DE3) cultures expressing the indicated VLCAD proteins in pET-21a.

Expression of VLCAD with missense mutations

Six previously reported patient missense mutations were chosen for study (Table 1), four of which had previously been characterized using mammalian expression systems (T220M, V243A, A450P, and R573W). Mutations A450P and L462P were of special interest as they are among the few missense mutations that have been reported in the C-terminal domain. Of the six mutant enzymes, five had measurable activity in crude E coli lysates using palmitoyl-CoA (C16:0) as substrate (Figure 2). The activity levels of T220M and V243A (3% and 22% of wild-type, respectively) agreed well with previous activity measurements in a mammalian expression system [5]. Mutant R429W, which has been associated with the severe disease phenotype in four patients [5], had only trace activity (0.2% of wild-type, Figure 2). Cultures expressing R573W, which was previously suggested to be a null mutation leading to severe disease [30], had no detectable VLCAD activity. Finally, extracts from cells expressing mutants A450P and L462P both had higher VLCAD activity than that obtained with the wild-type ΔEx3 vector as well as greater amounts of antigen as detected by western blot (Figure 2). The incongruent finding that the A450P and L462P variants are associated with disease despite normal enzyme activity led to further characterization of these two enzymes.

Table 1.

Human VLCAD mutations selected for expression in the prokaryotic system.

| Mutation | Amino Acid Change | Location | Number of Patients | Disease Phenotype | Previous Characterization in Eukaryotic Expression Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 779C>T | T220M | ACD domain | 5 [5] | Mild | 5% activity, reduced antigen [5] |

| 848T>C | V243A | ACD domain | 17[5, 37–39] | Mild | 20% activity, reduced antigen [5] |

| 1405C>T | R429W | ACD domain | 4 [5] | Severe | NA |

| 1468G>C | A450P | Carboxy terminus | 1 [18] | Mild | Altered substrate preference [18] |

| 1505T>C | L462P | Carboxy terminus | 1 [5] | Mild | NA |

| 1837C>T | R573W | Carboxy terminus | 1 [5] | Severe | No VLCAD dimers formed [30] |

Amino acid numbering refers to the mature sequence following cleavage of mitochondrial leader. ACD, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. Bracketed numbers indicate references.

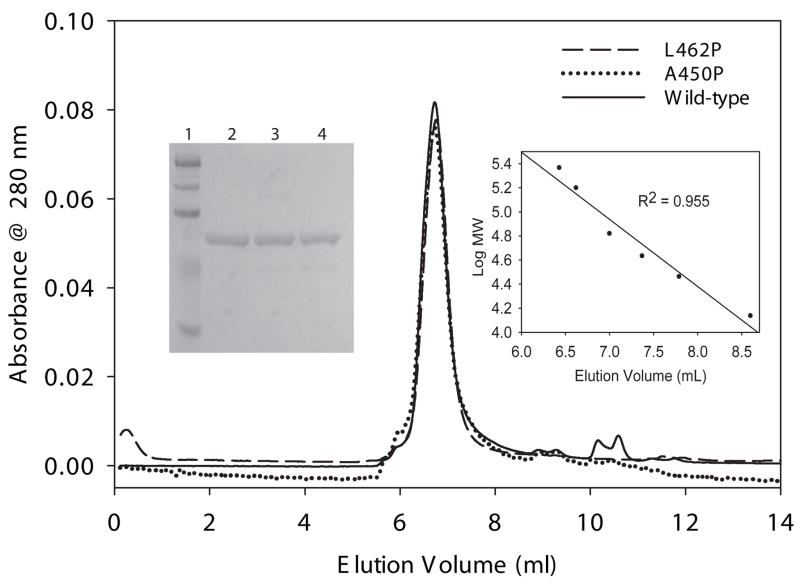

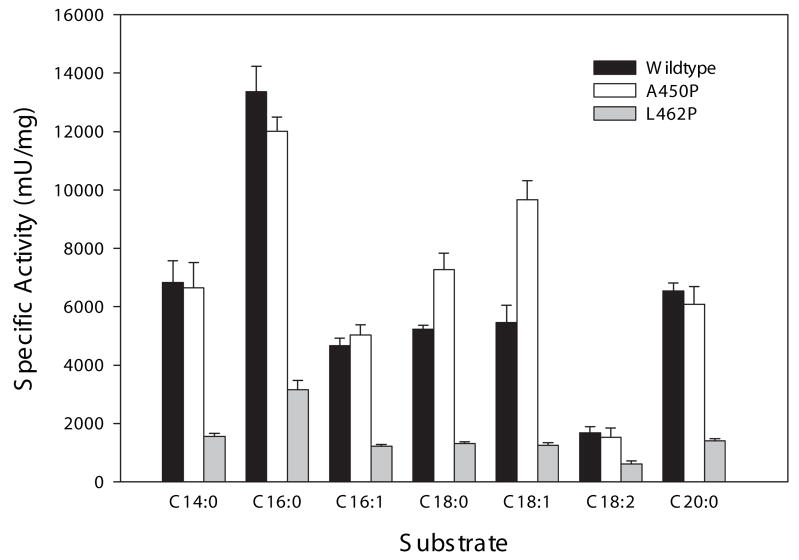

Substrate specificity of the A450P and L462P mutant enzymes

The A450P mutant VLCAD was previously expressed and partially purified using a baculovirus system and shown to have near normal activity when myristoyl-CoA (C14:0) was used as substrate but significantly reduced activity with longer chain-length substrates (C16:0 to C20:0) [18]. In contrast, the A450P mutant enzyme produced in our C43 (DE3) E coli crude extracts had high activity with C16:0. To further study the substrate specificities of A450P and L462P both mutant enzymes and the wild type ΔEx3 variant were purified to homogeneity from E coli extracts. All three purified proteins were determined to be approximately 120 kDa using HPLC gel-filtration chromatography indicating that they have the same homodimeric structure as full-length VLCAD (Figure 3). Enzyme activity was then measured using acyl-CoA substrates of carbon chain lengths ranging from C14 to C20 including the unsaturated carbon backbones cis-9-C16:1, cis-9-C18:1, and cis-9,cis-12-C18:2. All three enzymes showed maximal activity with C16:0 as substrate (Figure 4). Compared to wild type, A450P mutant enzyme had equal or higher activity with all substrates tested while L462P activities ranged from 25% to 35% of the wild type ΔEx3 VLCAD enzyme. When this data was expressed as a percentage of C16:0 activity, so that the relative activities across the panel of substrates could be compared, the substrate preference of the L462P mutant was nearly identical to that of wild type enzyme while the A450P enzyme showed a somewhat increased preference for C18:0 and C18:1 (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Molecular sizing of wild type and mutant VLCADs. 50 μg of each purified VLCAD protein (as shown on a Coomassie-stained 10% SDS-PAGE gel in the lefthand inset: Lane 1, molecular weight markers; Lane 2, 5 μg purified ΔEx3 VLCAD; Lane 3, 5 μg purified A450P VLCAD; and Lane 4, 5 μg purified L462P VLCAD) was subjected to gel filtration chromatography and molecular mass was determined using the calibration curve shown in the righthand inset (standards used were: ribonuclease A, 13.7 kDa; carbonic anhydrase, 29 kDa; ovalbumin, 43 kDa; albumin, 67 kDa; aldolase, 158 kDa; and catalase, 232 kDa). The calculated molecular masses were 118 kDa, 119 kDa, and 122 kDa for L462P, A450P, and wild-type ΔEx3 VLCAD, respectively.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the enzyme activity of purified wild-type VLCAD versus mutants A450P and L462P with various acyl-CoA substrates. Panel (A) shows specific activity assayed with myristoyl-CoA (C14:0), palmitoyl-CoA (C16:0), palmitoleoyl-CoA (C16:1), stearoyl-CoA (C18:0), oleoyl-CoA (C18:1), linoleoyl-CoA (C18:2), and arachidonyl-CoA (C20:0). Panel (B) depicts these same data but the specific activity with C16:0-CoA has been set to 100% and the relative activities with other substrates are shown as a percentage of C16:0 activity. Bars represent means and standard deviations of triplicate assays. Black bars show wild type activity, light gray bars show A450P activity, and dark gray bars show L462P activity.

Table 2.

Substrate preference of wild-type, A450P, and L462P VLCAD enzymes.

| Enzyme | C14:0 | C16:0 | C16:1 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C20:0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 51.1 | 100 | 34.8 | 39.0 | 40.8 | 12.5 | 48.9 |

| A450P | 55.2 | 100 | 41.9 | 60.6 | 80.5 | 12.6 | 50.7 |

| L462P | 49.3 | 100 | 38.4 | 41.6 | 39.8 | 19.4 | 44.3 |

Enzyme activity with palmitoyl-CoA (C16:0) was highest for all three enzymes and was set to 100. Activity data for the other substrates is shown as a percentage of the C16:0 activity.

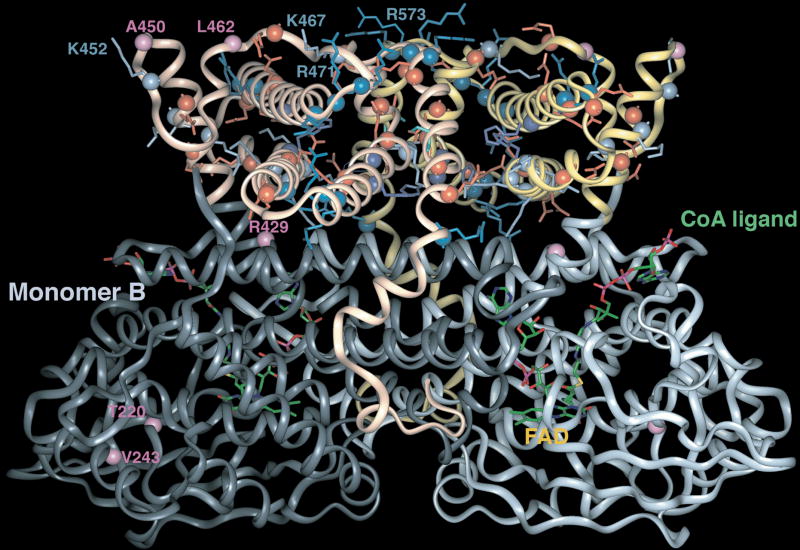

Molecular modeling of VLCAD

While the prokaryotic expression experiments showed the L462P mutant VLCAD to have reduced stability and activity, the functional deficit induced by the A450P mutation was still unclear. The C-terminal domains of VLCAD and ACAD9 have been hypothesized to interact with the mitochondrial membrane because other members of the ACD family lacking this domain localize to the mitochondrial matrix. To explore the possible function of the C-terminal domain we used the known crystal structures of several ACDs and that of a member of the related AOX superfamily to generate a molecular model of the VLCAD homodimer (Figure 5). The model predicts that the ACD domain of VLCAD, contained in the first 430 amino acids, forms a structure very similar to other ACD family members. Amino acid E422 has been thought to be the catalytic residue based on sequence alignment and site-directed mutagenesis experiments [31]. Our model confirms that E422 is indeed in the correct position to act as the catalytic base that initiates catalysis through abstraction of the α-proton from the acyl moiety of the substrate. The extended C-terminal domain, unique to VLCAD and ACAD9, is predicted to be comprised of a series of α-helices that assume an antiparallel super-secondary structure. In the VLCAD homodimer the two C-termini form an axis of symmetry that runs at an angle to the axis of symmetry of the ACD domains, such that the C-termini appear to substitute for the stabilizing function of the opposing dimer as seen in the solved crystal structures of the homotetrameric family members. Additionally, several exposed basic amino acid residues in the C-termini, namely K452, K467, R470, R471, R472, R544, R491, R498, R573 and R575, seem to be positioned to form a positively charged interface that could mediate the binding of VLCAD to the inner mitochondrial membrane by either interacting directly with the negatively charged lipid bilayer or by binding to resident inner membrane proteins. All these residues except R491, R498, and R575 are invariant in known and putative VLCADs from various species including chimpanzee, bovine, pig, mouse, rat, dog, and zebrafish.

Figure 5.

Ribbon representation of a VLCAD homodimer model. The computer generated model was based on the known structures of several ACDs and straight chain acyl-CoA oxidase C-terminus (AOX). The six amino acids studied in mutagenesis experiments are shown in purple on either monomer A or B. Basic residues of the C-terminus are rendered in blue and acidic ones in red. The positively charged area at the top of the model is hypothesized to interact with the inner mitochondrial membrane.

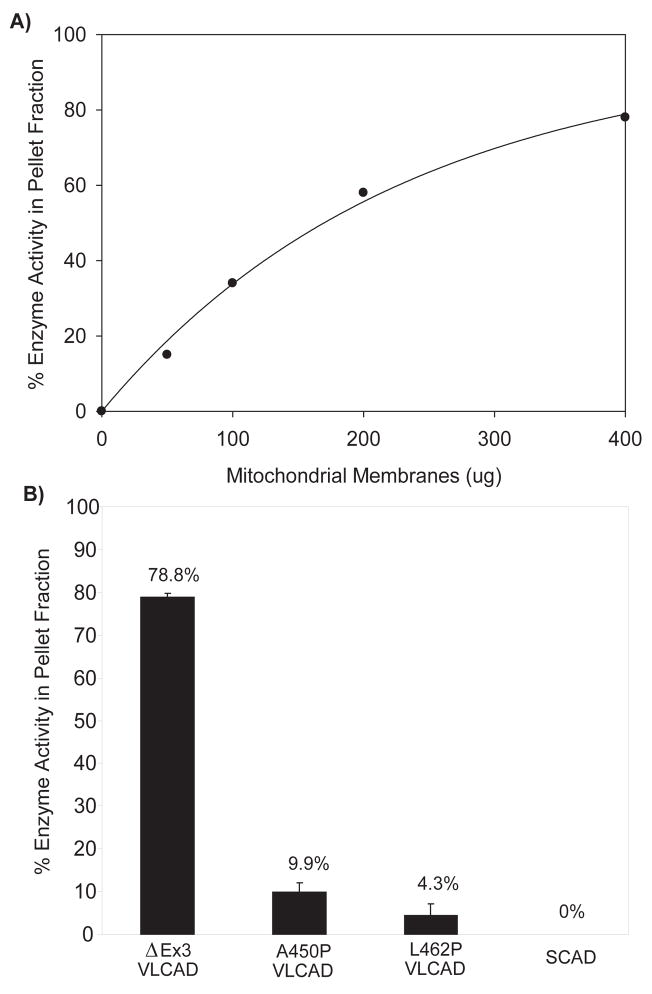

Interaction of wild type ΔEx3 variant and A450P and L462P mutant enzymes with mitochondrial membranes

The charged surface seen in the three-dimensional molecular model indicates a possible mechanism by which the VLCAD C-terminus mediates binding to the inner mitochondrial membrane. Residues A450 and L462 both map to a subdomain of VLCAD (G448–Q468) that by sequence alignment is equivalent to an apparently disordered area in the AOX crystal structure. This portion of VLCAD is predicted to be located adjacent to the positively charged surface and we hypothesized that the A450P and L462P substitutions may interfere with membrane binding. To investigate this hypothesis we employed an in vitro assay in which the purified VLCAD proteins were incubated with a washed rat liver mitochondria membrane preparation. After 30 minutes of incubation the membrane suspension was subjected to centrifugation and the pellet and supernatant were assayed for enzymatic activity with C16:0-CoA. Under these conditions wild type ΔEx3 variant VLCAD bound to the mitochondrial membranes in a dose-dependent fashion with nearly 80% of the enzyme recoverable in the pellet at high membrane concentration (Figure 6a). VLCAD binding was not reduced by pre-boiling the mitochondrial membranes (not shown). Next, purified VLCAD mutants A450P and L462P were tested for membrane binding with the highest concentration of membranes used in the wild type binding experiments. In contrast to wild type VLCAD, both mutant enzymes were found to remain predominately in the supernatant after centrifugation (90% and 96% for the A450P and L462P mutant proteins, respectively versus 21% of wild type enzyme) (Figure 6b). Purified SCAD, a homotetrameric ACD which localizes to the mitochondrial matrix, remained entirely in the supernatant fraction when incubated with mitochondrial membranes.

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial membrane binding is impaired in VLCAD mutants A450P and L462P. (A) Wild-type ΔEx3 VLCAD shows dose-dependent binding to mitochondrial membranes in vitro. A constant amount of pure VLCAD (3 μg) was incubated with increasing amounts of mitochondrial membranes and the percentage of enzyme activity appearing in the pellet fraction following centrifugation was determined. (B) Binding of mutant enzymes A450P and L462P to mitochondrial membranes as compared to wild-type VLCAD. 3 μg of purified wild type or mutant enzyme was incubated with 400 μg of mitochondrial membranes and the percentage of enzyme activity appearing in the pellet fraction following centrifugation was determined. SCAD, a mitochondrial matrix ACD enzyme, was used as a control and showed no membrane binding.

DISCUSSION

As with many inborn errors of metabolism, VLCAD deficiency presents with a wide range in severity of symptoms. While some genotype/phenotype correlations are suggested on the basis of mutation analysis, the relationship is imperfect. Functional studies have been restricted due to the lack of a robust prokaryotic expression system to allow production of large enough quantities of wild type and mutant enzymes. In this report, we describe a prokaryotic expression system that achieves this end. While expression of the previously recognized VLCAD cDNA in E coli was unsuccessful, an exon 3 splice variant identified in the databases that is missing 22 amino acids near the N-terminus was stable enough to allow purification. Interestingly, ACAD9, which similarly expresses well in E coli, also lacks the region homologous to VLCAD exon 3. The VLCAD ΔEx3 splice variant was first identified in an Israeli patient with the severe form of VLCAD deficiency [32]. The patient was homozygous for two alterations– 194C>T (P65L), which lies within exon 3, and 739A>C (K247Q). The P65L amino acid change had no effect on enzyme activity but appeared to be associated with a greatly increased level of exon 3 skipping in an in vivo mRNA splicing experiment. The mechanism by which this exonic mutation increases exon 3 skipping is not clear but was proposed to involve disruption of an exonic splicing enhancer. It is not known what the population frequency of the P65L alteration is or what degree of exon 3 skipping occurs in the absence of this mutation. Our prokaryotic expression experiments indicate that the ΔE3 variant produces a stable protein with very high specific activity and has a substrate specificity profile similar to that previously reported for VLCAD purified from native sources or expressed in mammalian systems [18, 33, 34]. Thus, it appeared that this variant would be useful for the investigation of the enzymatic properties and structure of wild type and mutant VLCAD.

To validate this supposition we introduced six mutations previously reported in VLCAD deficient patients into the ΔEx3 variant cDNA. Four of the mutations (T220M, V243A, A450P, and R573W) had been previously investigated using eukaryotic systems. The T220M and V243A mutant proteins were over-expressed in COS-7 cells. The T220M enzyme was detected in greatly reduced quantities with only 5% activity compared to wild type while the V243A mutant was produced to ~20% of wild type VLCAD antigen levels with 20–25% activity [5]. Our recombinant enzymes behave similarly. Crude cellular extracts from E coli expressing the T220M mutant had 3% of the activity obtained with the wild type insert and very little detectable VLCAD antigen (Figure 3) while expression of the V243A mutant yielded ~20% activity and ~20% antigen compared to wild type VLCAD. The correlation between amount of detectable VLCAD antigen and enzyme activity suggests that the T220M and V243A mutations may affect folding and/or stability of the abnormal proteins. A failed attempt to purify the V243A enzyme is a further indication that this mutant may be unstable. Expression of the T220M mutant was too low to allow purification.

Only a few missense mutations have been reproducibly linked to the severe disease phenotype in VLCAD deficiency including R429W and R573W [5, 14]. When expressed under conditions identical to the wild-type ΔEx3 VLCAD, the R429W and R573W cDNAs yielded no or very minimal VLCAD antigen (Figure 2) suggesting these mutations may severely affect either enzyme assembly or stability. These results provide a suitable explanation for the severe clinical phenotype of VLCAD deficiency found in four patients with R429W and one patient with R573W. In our three-dimensional molecular model (Figure 5), R573 lies at a turn between two helices in the C-terminal domain. These helices lie at the monomer-monomer interface and may be critical for stabilizing the VLCAD homodimeric tertiary structure. Substitution with a bulky tryptophan residue (R573W) would be predicted to interfere with dimerization. This is supported by previous experiments expressing the R573W mutant using a baculovirus system in which the enzyme showed severe folding defects and was detected only as monomers [14, 30].

While the function of the long C-terminal domain of VLCAD is unknown, it has generally been assumed to mediate binding of the enzyme to the inner mitochondrial membrane [13, 14]. This 180 amino acid section of VLCAD bears no homology to other ACDs with solved three-dimensional structures but has some homology to proteins in the acyl-CoA oxidase (AOX) family. Computer modeling based on the known structures of other ACDs for the conserved ACD domain and straight-chain AOX for the 180 amino acid C-terminal domain was useful in providing clues for the possible function of the C-terminal domain. One major question regarding the structure of VLCAD is its quaternary structure. All ACD structures solved thus far are homotetramers arranged as a “dimer of dimers.” Multiple residues from an opposing dimer play a role in stabilizing the non-covalently attached FAD cofactor in the holoenzyme and substrate interaction during catalysis. In our model of the dimeric VLCAD the C-termini are predicted to assume a configuration with multiple flexible α-helices that substitute for the second dimer present in the tetrameric ACDs. Additionally, a number of positively charged residues can be seen to align along the surface of the C-terminal in our model. This conformation, we hypothesize, provides a domain that could interact directly with the negatively charged inner mitochondrial membrane. The reactivity of the positive charges is supported by the fact that VLCAD, unlike other known ACDs, binds tightly to negatively charged chromatography resins. The current experiments show that recombinant VLCAD can bind to isolated mitochondrial membranes that have been washed to remove all peripherally-associated membrane proteins. Boiling the membranes, which should denature the remaining integral membrane proteins, did not reduce VLCAD binding (not shown). Our model and membrane binding experiments suggest a direct interaction between the surface formed by the VLCAD C-terminus and the lipid bilayer. However, the hyperbolic nature of Figure 6a, where a constant amount of VLCAD was titrated with increasing amounts of washed membranes, indicates that the binding interaction may not be governed by a simple equilibrium. Further experiments are needed to determine the exact components of the mitochondrial membrane that interact with VLCAD.

The L462P mutant showed greatly decreased membrane binding as well as decreased activity. Interestingly, the enzymatic activity of L462P in E coli crude extract was higher than wild-type VLCAD crude extract (Figure 2) but in the purified state activity was reduced to 25%–35% of the wild-type enzyme. This discrepancy is likely due to enzyme stability. While we did not directly test the stability of the L462P mutant, there was circumstantial evidence to support this conclusion. The L462P mutant was more difficult to purify than the other enzymes with lower yield. Additionally, L462P was more labile than the wild type and A450P enzymes, requiring the presence of glycerol for stability when diluted for enzyme activity assays. The ETF fluorescence reduction assay is highly sensitive and requires significant dilution when purified enzymes are assayed, potentially causing partial unfolding and thus lower activity measurements.

In the case of the A450P enzyme, reduced membrane binding was the only identifiable biochemical abnormality. The A450P mutation was originally detected in one of 14 VLCAD patients who had been thought to be deficient in long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) prior to the discovery of the VLCAD gene [35]. The patient (number 14 in the original report) was later found to have a small deletion on one VLCAD allele and the A450P mutation on the other allele [18]. She was diagnosed at age 8 with stress-induced myopathy and never suffered an acute decompensation or showed any indication of hypoglycemia [35]. VLCAD antigen levels in cultured fibroblasts were only modestly reduced, approaching the normal range [36]. The presence of disease in this patient despite substantial VLCAD antigen suggested that the A450P substitution was not a benign polymorphism. Furthermore, the A450P mutant enzyme produced by baculovirus expression showed reduced activity with substrates longer than 14 carbons [18]. In the current study, we have found this purified mutant enzyme to actually have somewhat higher activity with C18:0- and C18:1-CoAs than purified wild-type ΔEx3 VLCAD. The disparity in these findings may be due to differences in the assay methods employed. In the original report, an artificial dye was used as the electron acceptor and the assay was performed in the presence of 0.2% detergent. Our assay employs ETF, the native electron acceptor for VLCAD, and does not include detergent. The latter conditions are more likely to reflect the substrate specificity of the mutant enzyme in vivo. Also, in our experience, VLCAD was qualitatively more difficult to assay than other ACDs we have studied. We find VLCAD to be quite sensitive to product inhibition, particularly when palmitoyl-CoA is used as substrate (data not shown). The substrate specificity of wild-type ΔEx3 enzyme is not significantly different from that previously reported for native full-length VLCAD, thus we presume that the lack of exon 3 in our construct does not contribute to the differences between our results for A450P and those of Souri et al [18]. However, it does remain possible that the ΔEx3 variant may influence substrate specificity in the context of certain mutations.

In summary, the ability to produce large quantities of recombinant VLCAD is a significant milestone in the study of this enzyme. Our knowledge of structure/function relationships in the dimeric, membrane-associated ACDs (VLCAD and ACAD9) is minimal compared to the tetrameric, matrix-soluble ACD family members. It will now be possible to produce enough recombinant VLCAD for X-ray crystallography, allowing the generation of the three-dimensional crystal structure of the enzyme. The VLCAD expression system will also be useful for the investigation of mutations found in VLCAD deficient patients. The six patient mutations examined in the current study demonstrated a variety of mechanisms of molecular pathogenesis, interfering with VLCAD protein folding, assembly, and stability. Moreover, in vitro binding experiments with wild type and mutant VLCAD proteins have provided the first direct proof that the C-terminal domain unique to VLCAD and ACAD9 plays a role in interaction with the mitochondrial membrane. Clinical disease in patients with these mutations– affecting interaction with the mitochondrial membrane despite considerable in vitro enzymatic activity– provides evidence that membrane binding is critical for proper VLCAD function in vivo.

Acknowledgments

JV was supported in part by NIH grants RO1DK45482 and RO1DK54936, and the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Tobacco Formula Funding.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gregersen N, Andresen BS, Corydon MJ, Corydon TJ, Olsen RK, Bolund L, Bross P. Mutation analysis in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation defects: Exemplified by acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiencies, with special focus on genotype-phenotype relationship. Hum Mutat. 2001;18:169–89. doi: 10.1002/humu.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweetman L, Williams JD. Branched chain organic acidurias. In: Scriver C, Beaudet AL, Sly W, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2125–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wanders RJA, Vreken P, Den Boer MEJ, Wijburg FA, Van Gennip AH, IJlst L. Disorders of mitochondrial fatty acyl-CoA β–oxidation. J Inher Metab Dis. 1999;22:442–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1005504223140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vockley J, Singh RH, Whiteman DA. Diagnosis and management of defects of mitochondrial beta-oxidation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002;5:601–9. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andresen BS, Olpin S, Poorthuis Bjhm, Scholte HR, Vianey-Saban C, Wanders R, Ijlst L, Morris A, Pourfarzam M, Bartlett K, Baumgartner ER, deKlerk JBC, Schroeder LD, Corydon TJ, Lund H, Winter V, Bross P, Bolund L, Gregersen N. Clear correlation of genotype with disease phenotype in very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:479–94. doi: 10.1086/302261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogilvie I, Pourfarzam M, Jackson S, Stockdale C, Bartlett K, Turnbull DM. Very long-chain acyl coenzyme-A dehydrogenase deficiency presenting with exercise-induced myoglobinuria. Neurology. 1994;44:467–73. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smelt AH, Poorthuis BJ, Onkenhout W, Scholte HR, Andresen BS, van Duinen SG, Gregersen N, Wintzen AR. Very long chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency with adult onset. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:540–4. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ensenauer R, He M, Willard JM, Goetzman ES, Corydon TJ, Vandahl BB, Mohsen AW, Isaya G, Vockley J. Human acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-9 plays a novel role in the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32309–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He M, Burghardt TP, Vockley J. A novel approach to the characterization of substrate specificity in short/branched chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37974–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen T, Riggs C, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Kim YS, Carpenter JF, Burghardt TP, Gregersen N, Vockley J. Purification and Characterization of two polymorphic variants of short chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase reveal reduction of catalytic activity and stability of the Gly185Ser enzyme. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11126–33. doi: 10.1021/bi026030r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen TV, Andresen BS, Corydon TJ, Ghisla S, Abd-El Razik N, Mohsen AW, Cederbaum SD, Roe DS, Roe CR, Lench NJ, Vockley J. Identification of isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase and its deficiency in humans. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;77:68–79. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohsen AA, Vockley J. High-level expression of an altered cDNA encoding human isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1995;160:263–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andresen BS, Bross P, Vianeysaban C, Divry P, Zabot MT, Roe CR, Nada MA, Byskov A, Kruse TA, Neve S, Kristiansen K, Knudsen I, Corydon MJ, Gregersen N. Cloning and characterization of human very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase cDNA, chromosomal assignment of the gene and identification in four patients of nine different mutations within the VLCAD gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:461–72. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Souri M, Aoyama T, Hoganson G, Hashimoto T. Very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase subunit assembles to the dimer form on mitochondrial inner membrane. FEBS Lett. 1998;426:187–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumon-Seignovert L, Cariot G, Vuillard L. The toxicity of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli: a comparison of overexpression in BL21(DE3), C41(DE3), and C43(DE3) Protein Expr Purif. 2004;37:203–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vockley J, Nagao M, Parimoo B, Tanaka K. The variant human isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase gene responsible for type-II isovaleric acidemia determines an RNA splicing error, leading to the deletion of the entire 2nd coding exon and the production of a truncated precursor protein that interacts poorly with mitochondrial import receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2494–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohsen AW, Anderson BD, Volchenboum SL, Battaile KP, Tiffany K, Roberts D, Kim JJ, Vockley J. Characterization of molecular defects in isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase in patients with isovaleric acidemia. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10325–35. doi: 10.1021/bi973096r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souri M, Aoyama T, Yamaguchi S, Hashimoto T. Relationship between structure and substrate-chain-length specificity of mitochondrial very-long-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase. Eur J Biochem. 1998;257:592–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2570592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frerman Frank E, Goodman Stephen I. Fluorometric assay of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases in normal and mutant human fibroblasts. Biochem Med. 1985;33:38–44. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(85)90124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumegi B, Srere PA. Binding of the enzymes of fatty acid beta-oxidation and some related enzymes to pig heart inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:8748–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barycki JJ, O’Brien LK, Bratt JM, Zhang RG, Sanishvili R, Strauss AW, Banaszak LJ. Biochemical characterization and crystal structure determination of human heart short chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase provide insights into catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5786–98. doi: 10.1021/bi9829027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battaile KP, Molin-Case J, Paschke R, Wang M, Bennett D, Vockley J, Kim J-JP. Crystal structure of rat short shain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase complexed with acetoacetyl-CoA; comparison with other acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12200–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djordjevic S, Pace CP, Stankovich MT, Kim JJP. Three-dimensional structure of butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase from Megasphaera esdenii. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2163–71. doi: 10.1021/bi00007a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Jung-Ja, Wang Ming. The three dimensional structure of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. Prog Clinical Biol Res. 1992;375:111–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JJ, Wu J. Structure of the medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase from pig liver mitochondria at 3-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;84:6677–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JJP, Wang M, Paschke R, Djordjevic S, Bennett DW, Vockley J. Three dimensional structures of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases: structural basis of substrate specificity. In: Yagi K, editor. Flavins and Flavoproteins 1993. New York: Walter deGruyter; 1994. pp. 273–82. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JJP, Wang M, Paschke R. Crystal structures of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase from pig liver mitochondria with and without substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7523–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiffany KA, Roberts DL, Wang M, Paschke R, Mohsen AWA, Vockley J, Kim JJP. Structure of human isovaleryl-coA dehydrogenase at 2.6 angstrom resolution - basis for substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8455–64. doi: 10.1021/bi970422u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiffany KD, Wang M, Paschke R, Mohsen AW, Vockley J, Kim JJ. Structural basis for substrate specificity in acyl-CoA dehydrogenases: What makes isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase specific for a branched chain substrate? Flavins and Flavoproteins. 1997;1996:649–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Souri M, Aoyama T, Orii K, Yamaguchi S, Hashimoto T. Mutation Analysis Of Very-Long-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme a Dehydrogenase (Vlcad) Deficiency - Identification and Characterization Of Mutant Vlcad Cdnas From Four Patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:97–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souri M, Aoyama T, Cox GF, Hashimoto T. Catalytic and FAD-binding residues of mitochondrial very long chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4227–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe H, Orii KE, Fukao T, Song XQ, Aoyama T, Jlst IL, Ruiter J, Wanders RJ, Kondo N. Molecular basis of very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in three Israeli patients: identification of a complex mutant allele with P65L and K247Q mutations, the former being an exonic mutation causing exon 3 skipping. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:430–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200005)15:5<430::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lea WP, Abbas AS, Sprecher H, Vockley J, Schulz H. Long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase is a key enzyme in the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta Molecular & Cell Biology of Lipids. 2000;31:2–3. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Izai K, Uchida Y, Orii T, Yamamoto S, Hashimoto T. Novel fatty acid β–oxidation enzymes in rat liver mitochondria. 1. Purification and properties of very-long-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1027–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hale DE, Stanley CA, Coates PM. The long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. In: Tanaka K, Coates PM, editors. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research: Fatty Acid Oxidation. Clinical, Biochemical and Molecular Aspects. New York: Alan R. Liss. Inc; 1990. pp. 303–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi S, Indo Y, Coates PM, Hashimoto T, Tanaka K. Identification of very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in 3 patients previously diagnosed with long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr Res. 1993;34:111–3. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199307000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voermans NC, van Engelen BG, Kluijtmans LA, Stikkelbroeck NM, Hermus AR. Rhabdomyolysis caused by an inherited metabolic disease: very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Am J Med. 2006;119:176–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boneh A, Andresen BS, Gregersen N, Ibrahim M, Tzanakos N, Peters H, Yaplito-Lee J, Pitt JJ. VLCAD deficiency: pitfalls in newborn screening and confirmation of diagnosis by mutation analysis. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;88:166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiekerkoetter U, Sun B, Zytkovicz T, Wanders R, Strauss AW, Wendel U. Ms/MS-based newborn and family screening detects asymptomatic patients with very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Pediatr. 2003;143:335–42. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]