Abstract

Synthesis of well-defined neoglycopolymer–protein biohybrid materials and a preliminary study focused on their ability of binding mammalian lectins and inducing immunological function is reported. Crucial intermediates for their preparation are well-defined maleimide-terminated neoglycopolymers (Mn = 8–30 kDa; Mw/Mn = 1.20–1.28) presenting multiple copies of mannose epitope units, obtained by combination of transition-metal-mediated living radical polymerization (TMM LRP) and Huisgen [2+3] cycloaddition. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was employed as single thiol-containing model protein, and the resulting bioconjugates were purified following two independent protocols and characterized by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, SDS PAGE, and SEC HPLC. The versatility of the synthetic strategy presented in this work was demonstrated by preparing a small library of conjugating glycopolymers that only differ from each other for their relative epitope density were prepared by coclicking of appropriate mixtures of mannopyranoside and galactopyranoside azides to the same polyalkyne scaffold intermediate. Surface plasmon resonance binding studies carried out using recombinant rat mannose-binding lectin (MBL) showed clear and dose-dependent MBL binding to glycopolymer-conjugated BSA. In addition, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) revealed that the neoglycopolymer–protein materials described in this work possess significantly enhanced capacity to activate complement via the lectin pathway when compared with native unmodified BSA.

Introduction

The post-genome era is one of the most challenging and exciting periods in the history of chemical and biological research. The study of oligosaccharides and lectins in the context of whole organisms–functional glycomics–is one of the most difficult yet crucial fields of post-genome analysis, with impact upon many biochemical and physiological processes such as pathogen–host interactions, cell adhesion, tissue integrity and homeostasis, and cell signaling.1-7 For example, recognition of microbial mannose-rich glycans by lectins of the immune system mediates important host defense mechanisms such as pathogen neutralization and phagocytosis.8 A major obstacle to rapid progress in the field of glycobiology and functional glycomics is the availability of purified oligosaccharides in sufficient quantities for inclusion in biological and biophysical analysis strategies.

Synthetic neoglycopolymers having multiple copies of monodentate sugar moieties are a class of macromolecular displays that have shown very promising results when employed as natural oligosaccharide mimics.9-13 The ability of some of these materials to specifically recognize lectins and cell surfaces has been the subject of extensive research, and now that the development of novel therapeutic strategies can be based on multivalent interactions a better understanding of these factors is required.13-16

A number of different strategies have been employed for the synthesis of the required multivalent carbohydrate ligands. Kiessling and co-workers have shown that polymers obtained by ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) can efficiently interact with both lectins17-28 and cells.29-34 Controlled radical polymerization techniques, in particular transition-metal-mediated living radical polymerization (TMM LRP, often called ATRP)35-38 and radical addition–fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization,39-42 have emerged as leading strategies to tailor-made neoglycopolymers with great control over a number of macromolecular features that include polymer architecture, chain length, and molecular weight distributions. One of the main advantages in using these techniques includes the high functional-group tolerance, which allows unprotected sugar monomers and polar protic and nonprotic solvents such as water and DMSO.12 Cyanoxyl-mediated radical polymerization has also been successfully employed by Chaikof and co-workers43-50 in a range of applications that include the preparation of glycocalyx-mimetic surfaces50 to the synthesis of lactose-sulfate-based synthetic heparin analogues potentially employable in areas related to therapeutic angiogenesis.48 The synthesis of well-defined synthetic glycopolymers by TMM LRP51-55 and RAFT polymerization56-60 and their use in a number of specific applications have been described, and the number of reports on this field is now rapidly growing.

Recently,28 we reported the synthesis of mannose- and/or galactose-containing neoglycopolymers by combination of TMM LRP and Cu(I)-catalyzed Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition,61,62 a “click chemistry”63 process. Our approach involved the grafting of sugar azides onto a polyalkyne “clickable” scaffold prepared by TMM LRP. Several azide-containing molecules could be simultaneously grafted in different proportions onto the same clickable scaffold, yielding libraries of different copolymers in a process that we named a “coclicking” approach.

The ability of neoglycopolymers to interact with lectins and cells is strongly dependent on their size, shape, structure, and binding epitope density (defined as “the mole fraction of specific binding epitopes incorporated into a multivalent backbone”26).3-15 For ligand comparative studies it is therefore of importance to have a set of synthetic tools that allows for the synthesis of libraries of polymers having identical macromolecular features, with the relative density of epitope binding units being the only variable. Postpolymerization processes appear to be the only way for achieving this goal as long as extremely efficient grafting processes are available. In this respect, use of “clickable”polymers is very promising,64 especially since a recent report by Munro and co-workers showed that some N-hydroxysuccinimide ester polymers, polymeric scaffolds often employed for polymer multiple functionalization, can undergo important side reactions during the final conjugation step that could potentially limit their applicability for the synthesis of multivalent therapeutics.65

Alternatively, controlled radical polymerization techniques allow for simple synthesis of well-defined glycopolymers by simply polymerization of appropriate sugar monomers. The main advantage of this approach is its simplicity, and the two synthetic strategies, postfunctionalization and direct polymerization of carbohydrate monomers, can now be regarded as complementary tools for the preparation of neoglycopolymers.

Another key advantage in using TMM LRP is that α-functional polymers can be easily prepared by simply choosing appropriate polymerization initiators; this has been exploited in the past for the synthesis of biohybrid materials by (poly)-peptide–polymer conjugation.46,66-70

In the present work we aimed to modify our “click” approach to glycopolymers for the synthesis of α-mannopyranoside-containing glycoprotein mimics suitable for probing interactions with mannose-binding lectin (MBL), a key mammalian lectin of the immune system. Mannoside structures are prevalent on the cell surfaces of many bacterial and fungal pathogens, their arrangements distinct from human mannoside glycans, thus being distinguishable from the human host. MBL is able to recognize these non-self-arrangements of mannoside residues and through binding in this way to pathogen surfaces is able to trigger the complement cascade, a powerful arm of the circulating innate immune system that subsequently opsonises the pathogens for phagocytosis as well as driving cellular pore formation that leads to pathogen cell destruction.

Essential polymeric starting materials are novel maleimide-terminated glycopolymers able to selectively react with the free-cysteine (Cys34) residue of bovine serum albumin (BSA)—an abundant model protein molecule.

Free cysteine residues are rare in native polypeptides, and when present, they constitute an excellent attachment site for protein modification as they are present in very discrete number (typically one) and their location is often identifiable. When necessary, the protein of interest can be genetically modified in order to obtain free cysteine residues in specific positions of the protein surface. Development of protein–glycopolymer conjugates carries potential for the generation of therapeutic agents and biological probes. Through site-directed conjugate formation, defined biological molecules with novel dual properties can be formed very easily. Protein components can potentially confer functions such as highly defined ligand binding, enzyme activity, and sources of specific amino acid sequences in tertiary structural motifs or in the case of immunological antigen presentation as digested peptides loaded onto major histocompatibility complex molecules. Glycopolymers can confer selective lectin binding and thus engagement with the counter-glycome in plasma, cells, and tissues. Mannose polymers are of particular interest due to the fact that a number of mammalian lectins associated with immune function have been shown to bind mannose-containing structures expressed on the surface of pathogens such as Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans, and lethal viruses such as HIV, Ebola, and Hepatitis C.71-74 In this study we focused upon modifying BSA, a protein that is inert with regard to the innate immune system, via conjugation of mannose glycopolymer in order to investigate binding to MBL, an acute phase C-type lectin of the immune system that triggers activation of the complement cascade–the fundamental and archetypal fluid-phase innate immune effector mechanism present in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and tissue mucosa.75,76

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of the α-Maleimide Neoglycopolymers.

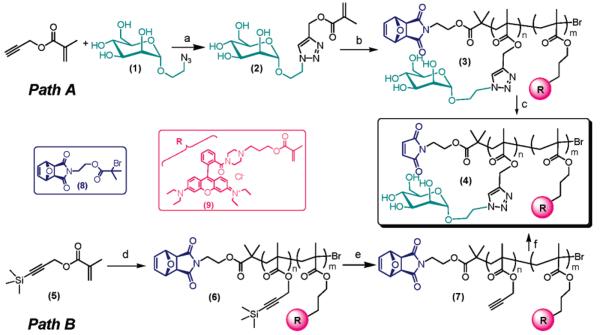

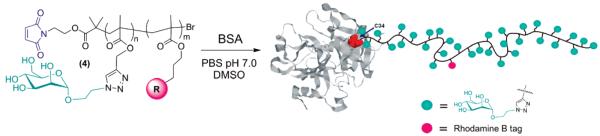

The required maleimide-terminated neoglycopolymers were prepared following two independent synthetic pathways (Scheme 2). Visibly fluorescent tag based on rhodamine B dye was introduced onto the polymers backbone in order to facilitate characterization of the relative protein conjugates and improve their traceability during the in vitro tests carried out in the present study.

Scheme 2.

a a Reagents and conditions: (a) CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, methanol/H2O (1:1 v/v), ambient temperature; (b) N-(ethyl)-2-pyridylmethanimide, Cu(I) Br, rhodamine B methacrylate 9, initiator 8, CH3OH/H2O 5:2 (v/v), ambient temperature; (c) toluene reflux, 18 h; (d) N-(ethyl)-2-pyridylmethanimide, Cu(I) Br, initiator 8, rhodamine B methacrylate 9, toluene, 30 °C; (e) TBAF·3H2O, THF, 0 °C to ambient temperature, 12 h; (f) (i) 1, (PPh3)3CuBr, Et3N, DMSO, ambient temperature, 2 days; (ii) toluene reflux, 18 h.

In the first protocol (Path A) the mannose-containing monomer 2 was readily prepared by Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of the mannose azide 1 and propargyl methacrylate using (PPh3)3CuBr as the catalyst. Polymerization of 2 in the presence of the maleimide-protected initiator 8 and fluorescent rhodamine B comonomer 9,77 using iminopyridine/Cu(I) Br as the catalytic system, afforded the macromolecular intermediate 3. This was then suspended in refluxing toluene for 18 h in order to remove the furan protecting group by retro-Diels–Alder reaction, leading to the maleimide-terminated neoglycopolymer 4. Alternatively, we found that the latter reaction occurred even in the solid state by simply leaving a powder sample of 3 in a vacuum oven at 80 °C overnight, yielding directly pure 4 and avoiding use of organic solvents and the need for a further final precipitation step.

The second synthetic strategy relies on the ability of poly- (propargyl methacrylate) to act as a versatile “clickable” polymeric scaffold able to efficiently react with sugar azides (Path B). The first step involves polymerization of the trimethylsilyl-protected propargyl methacrylate 5 in toluene, using iminopyridine/Cu(I) Br as the catalyst, in the presence of the initiator 8. Removal of the trimethylsilyl groups with TBAF in THF followed by clicking of the α-mannopyranoside azide 1 in DMSO and retro-Diels–Alder deprotection of the maleimide moiety afforded the expected maleimide-terminated mannose-containing polymer 4.

In the polymerization steps the first-order kinetic plots showed some deviation from linearity, yet the linear increase of Mn with monomer conversion and the narrow molecular weight distributions indicate that polymerization occurred in a controlled fashion (see Supporting Information).

Both synthetic approaches developed led to the desired maleimide-terminated polymers (Tables 1 and 2). Particular effort was spent in order to further simplify the synthetic protocol presented in this study. For example, mannose azide building block 1 was originally prepared following a well-established four-step procedure (see Supporting Information).78 Subsequently, we employed an alternative two-step procedure starting from unprotected D-mannose by first reacting the sugar with 2-bromoethanol at 90 °C in the presence of Amberlite IR-120 acid catalyst and then converting the resulting α-2′-bromoethyl-d-mannopyranoside into the desired mannose azide 1 with sodium azide in refluxing water/acetone mixture.79

Table 1.

Polymers Prepared in This Study

| polymer | DP (NMR) | Mn (NMR) (kDa) | Mw/Mn (SEC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 70 | 26.1 | 1.20c |

| 3b | 20 | 7.5 | 1.22c |

| 4a a | 74 | 27.6 | 1.20d |

| 4b a | 22 | 8.2 | 1.23d |

| 6 | 41 | 8.0 | 1.22c |

| 7 | 40 | 5.0 | 1.25c |

| 4c b | 44 | 16.4 | 1.28d |

Prepared via path A.

Prepared via path B.

Determined by SEC using CHCl3/Et3N 95:5 as the mobile phase.

Determined by aqueous SEC.

Table 2.

Maleimide-Terminated Polymers Featuring Different Mannose Density Prepared in This Study

| polymer | % mannose | % galactose | DP (NMR) | Mn (NMR) (kDa) | Mw/Mn(SEC)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | 100 | 0 | 139 | 52.3 | 1.26 |

| 24 | 75 | 25 | 141 | 53.1 | 1.25 |

| 25 | 50 | 50 | 139 | 52.3 | 1.25 |

| 26 | 25 | 75 | 136 | 51.1 | 1.26 |

| 27 | 0 | 100 | 138 | 51.9 | 1.25 |

Obtained by SEC analysis using DMF as the mobile phase and RI detection.

Synthesis of BSA Glycoprotein Mimics

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) is a commercially available 66 kDa protein that is often chosen as a model single-thiol-containing substrate. Its free Cys34 residue is generally regarded as the attachment site of choice for BSA site-specific conjugation. In the past both we68 and Maynard67 have shown that BSA can be conjugated with functional polymers obtained by controlled radical polymerization bearing chain ends able to react selectively with free thiol-containing (poly)peptides. In addition, BSA had been employed as a protein carrier for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of N-glycan-containing neoglycoproteins,80 and it appeared, therefore, to be a suitable substrate to be employed in our study.

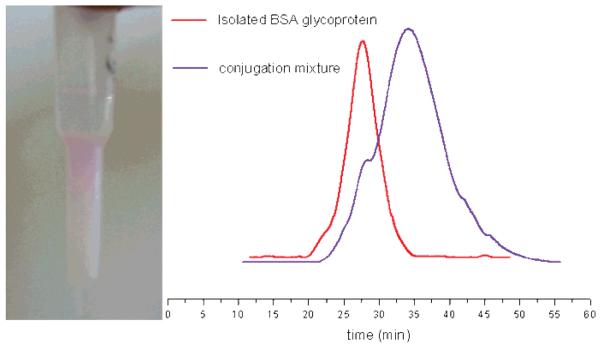

In the present work, glycoconjugate 10 was obtained by reaction of maleimide-terminated display 4a with BSA in 1:1 DMSO:PBS (50 mM, pH 7.0) (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the Glycoprotein Mimic 10 Obtained from Neoglycopolymer 4a

Several reaction conditions and purification protocols were explored for the conjugation reaction. In particular, an excess of both glycopolymer 4a and BSA protein, 10:1 and 1:10 mol/ mol, respectively, was successfully employed.

In the former case, the excess of unreacted maleimide polymer 4a was removed by repeated SEC purifications, while unreacted BSA and BSA dimer were separated by affinity chromatography using an agarose-immobilized Concanavalin A (Con A) column. Con A is a 26 kDa lectin (normally forming dimers or tetramers depending on the pH) extracted from Jack Beans that specifically recognize α-mannopyranoside sugar moieties. When the mixture obtained from SEC purification was passed through the affinity chromatography column, only the bioconjugate 10 was able to selectively interact with the Con A while the unreacted BSA and BSA dimer were rapidly eluted (Figure 1). 10 was then released from the column by simply washing the latter with a 1.0 M solution of d-mannose, a monovalent competitive ligand for Con A.

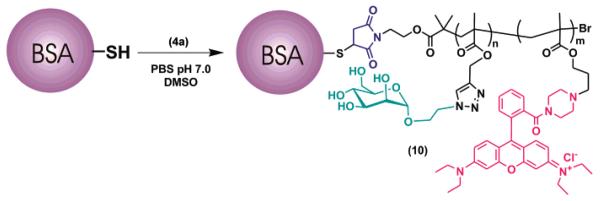

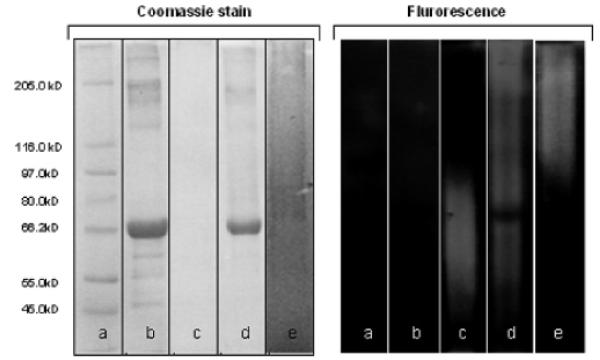

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE [Coomassie staining (left) and UV excitation at λ = 302 nm (right)] for the conjugation reaction of BSA with 4a: (a) MW markers; (b) native BSA; (c) glycopolymer 4a; (d) BSA with 10 equiv of 4a: conjugation mixture; (e) 10 purified by SEC followed by affinity chromatography.

This protocol allowed for isolation of the pure 10 biohybrid material as confirmed by SDS-PAGE and SEC analysis (Figure 1). It was evident from SDS-PAGE analysis of the crude product that some unreacted BSA was still present at the end of the conjugation reaction. This result agreed well with previous reports that indicated that only 36–69% of the BSA molecules present in commercially available samples have the free cysteine thiol required for protein conjugation.68,81-83 SDS-PAGE analysis also showed the absence of both BSA and BSA dimer in the final purified sample. SEC chromatography analysis of the purified conjugate 10 confirmed the presence of a fluorescent product with a molecular mass higher than BSA, in full agreement with the SDS-PAGE results (Figure 2).

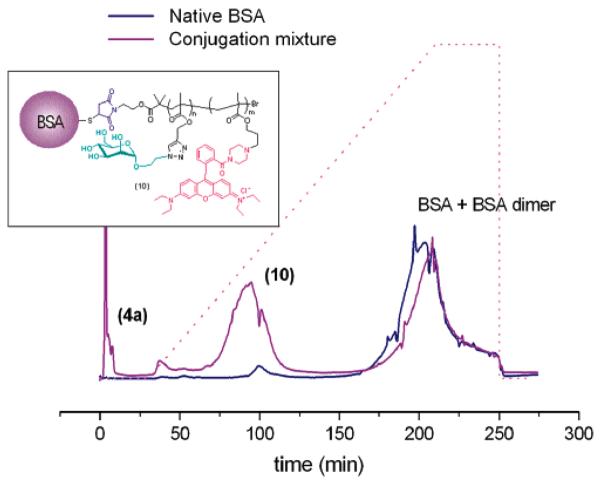

Figure 2.

BSA + maleimide glycopolymer 4a (10 equiv). (Left) Purification of conjugate 10 through an immobilized Concanavalin A column before eluting with 1.0 M mannose solution. (Right) SEC analysis of the conjugation reaction mixture (purple) and the final purified product 10. UV detection (λ = 280 nm) was employed.

The ability of 10 to interact strongly with the Con A lectin during affinity chromatography was in itself a preliminary direct evidence of the ability of this biohybrid material to act as a multivalent ligand for lectin recognition.

Ion-exchange chromatography was used for the case in which a 1:10 glycopolymer 4a:BSA molar ratio was employed in an attempt to simplify the purification process of the glycoprotein mimic 10. Optimum results were obtained by anion-exchange chromatography using a Source Q column in 20 mM TRIS buffer at pH 9.0. Under these experimental conditions the unreacted maleimide-terminated polymer 4a was not retained, while 10 showed a retention time between that of free polymer and BSA and BSA dimer (Figure 3). SEC analysis of the conjugate 10 isolated using this method confirmed that the two purification protocols developed were equivalent in terms of purity of the desired glycoprotein mimic 10 (see Supporting Information), although use of ion-exchange chromatography appeared to be more suitable for large-scale purification processes. The two purification processes are suitable for purification of crude mixtures obtained from both conjugation protocols with the SEC + affinity chromatography protocol that appeared to be less indicated for the case in which an excess of conjugating glycopolymer was employed due to the rather tedious SEC purification of the excess of unreacted glycopolymer from the polymer–protein conjugate 10.

Figure 3.

BSA (10 equiv) + maleimide glycopolymer 4a. FPLC anion-exchange chromatography purification of the conjugate 10 using Source Q column in 20 mM TRIS buffer at pH 9.0 as the mobile phase. A gradient of NaCl (pink dotted line) was used in order to elute the protein-based products.

Glycoprotein Mimics with Different Mannose Binding Unit Density

Recognition of lectin receptors is dependent on the length of the polydentate ligand counterpart21 as well as the density of the binding epitopes present in the neoglycopolymer.26,28 This makes the development of efficient and reliable strategies for the synthesis of polyvalent ligands bearing multiple binding epitopes of particular importance.

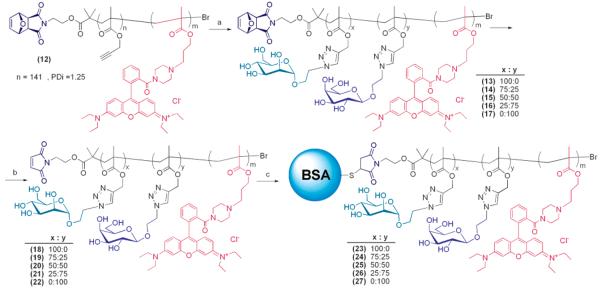

Once the necessary synthetic pathways and purification processes for the glycoconjugates were developed, a library of conjugating neoglycopolymers differing from each other for the relative density of mannose epitopes was prepared following a coclicking approach28 (Scheme 4) in order to further demonstrate the efficiency of the strategy presented in this work. As reported previously, libraries of glycopolymers identical in terms of macromolecular features (Mn, PDi, macromolecular architecture) can be obtain by simply introducing appropriate mixtures of different sugar azides in the reaction feed. BSA glycoconjugates 23–27 were then prepared using a 10:1 BSA to glycopolymer molar ratio and purified by anion-exchange chromatography.

Scheme 4.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) α-2′-azidoethyl-d-mannopyranoside 1/β-2′-azidoethyl-d-galactopyranoside 28, (PPh3)3CuBr, Et3N, DMSO, ambient temperature, 2 days; (b) reduced pressure, 80 °C, solid state, 12 h; (c) BSA (10 equiv), DMSO:PBS (50 mM, pH 7.0).

Circular dichroism (CD) analysis of the conjugates 23–27 was performed in order to evaluate the influence of the conjugated glycopolymer onto the secondary structure of BSA. α-Helix and β-sheet contents were found to be 51–65% and 0–2%, respectively, values that do not significantly differ from 54% α-helix and 1% β-sheet that was found for native BSA under identical conditions.

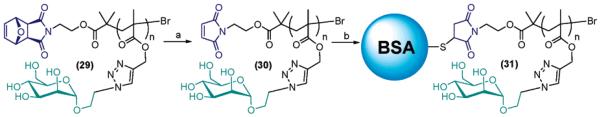

Pseudo-esterase activity of the protein part of our conjugate was assessed using p-nitrophenol acetate as model ester substrate in 50 mM PBS, pH 8.5. Since this assay relies on the spectophotometric detection (λ = 405 nm) of the p-nitrophenolate ion produced by hydrolysis of the ester substrate, our rhodamine B-tagged conjugates appeared to be unsuitable for such a test due to their non-negligible absorbance at 405 nm. A non-rhodamine-tagged biohybrid material, 31, was therefore prepared by direct polymerization of the mannose methacrylate monomer 2 in methanol/water 5:2 v/v at ambient temperature in the presence of the initiator 8 (Scheme 5). Retro-Diels–Alder removal of the furan protecting group followed by protein conjugation using an excess of BSA afforded the desired conjugate 31.

Scheme 5.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) toluene reflux, 18 h; (b) BSA (10 equiv) DMSO:PBS (50 mM, pH 7.0).

Pseudo-esterase assay84-86 revealed that 31 had an activity comparable with that of the BSA starting material (see Supporting Information), which further confirmed that the experimental conditions employed for both conjugation and purification of our biohybrid materials did not damage the protein part of the conjugates.

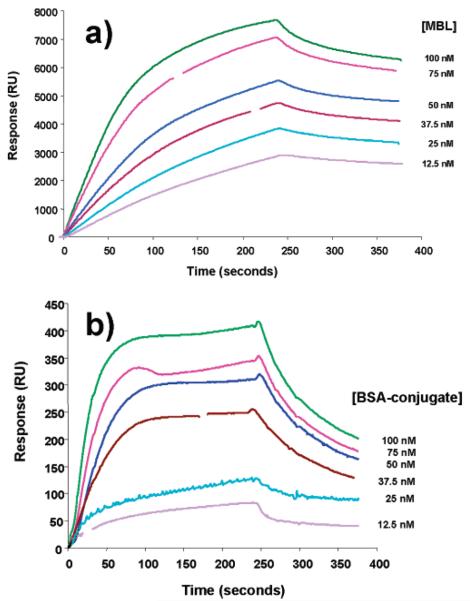

Binding studies using surface plasmon resonance (BIAcore) were carried out to examine glycopolymer–BSA conjugate interactions with recombinant rat mannose-binding lectin (MBL). Conjugates and unmodified BSA were immobilized in equal quantities on parallel flow cells within a CM5 sensor chip and sensorgrams recorded with MBL in the fluid-phase at concentrations indicated in Figure 4. Correction for background binding was achieved through subtraction of parallel sensorgram readings from hemeoglobin-coated flow cells. Clear and dose-dependent MBL binding to glycopolymer-conjugated BSA was observed within the physiological range, which is typically 20 nM, in stark contrast to plain BSA where no signal was observed (data not shown). Although MBL exists in vitro and in vivo as a heterogeneous collection of oligomers, average kinetic values were calculated for MBL binding to immobilized polymer giving a kon rate of 1.2 ± 0.45 × 105 M−1 s−1 and a koff rate of 7.3 ± 2.3 × 10−4 s−1 with a KD of 7.9 ± 4.5 × 10−9. Binding of fluid-phase glycopolymer-conjugated BSA to immobilized MBL was positive but gave lower absolute signal and showed different curve characteristics with a substantially faster dissociation curve (Figure 4b). This indicates the likely effects of multiple protein–sugar contacts required to increase avidity, but we acknowledge that immobilization of MBL on the CM5 surface may substantially effect its binding properties. Binding was not observed in either case when d-mannose was introduced into the analyte at 10 mM (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis of immobilized BSA–glycopolymer conjugate 10 with fluid phase mannose binding lectin (MBL) (a), and immobilized MBL with fluid phase BSA–glycopolymer conjugate (b). Due to the naturally heterogeneous nature of MBL oligomers, concentrations of fluid-phase MBL on immobilized BSA–conjugate are indicated assuming a molecular weight of 75 kD. (b) An average molecular weight of 100 kDa is assumed for indications of fluid-phase BSA–conjugate.

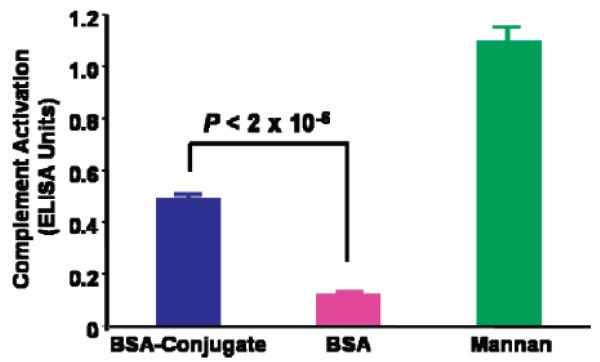

Functional analysis of the glycopolymer–BSA conjugates was performed using a protocol designed to measure complement system activation. Compared with BSA, immobilized glycopolymer–BSA conjugate showed significantly enhanced capacity to activate complement via the lectin pathway as assessed by quantitative measurement of pathway-dependent complement protein deposition by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Student's t test, P < 2 × 10−6; Figure 5). Thus, incorporation of the glycopolymer-modified BSA imparts the inert protein with innate immune system interaction properties.

Figure 5.

Detection of complement system activation. BSA–conjugate 10, BSA, and yeast mannan were immobilized on microwell plates and exposed to diluted human serum. Values indicate the level of activated complement C9 deposition resulting from positive cascade triggering, as determined by a subsequent ELISA-style assay involving p-nitrophenol detection at λ = 405 nm. ELISA units obtained as direct absorbance at 405 nm values with reagent blank values deducted

Conclusions

Glycoproteins are potent biological molecules active through the union of structural and chemical properties imparted by both specific protein and carbohydrate components. Neoglycopolymers represent very attractive molecules through which defined macrocarbohydrate properties can be generated rapidly and with high yield, providing a realistic alternative in many cases to scarce and prohibitively expensive natural oligosaccharides.

In this work we introduced a simple and general method for the synthesis of glycoprotein mimics. Well-defined maleimide-terminated neoglicopolymers (Mn = 8–30 kDa; Mw/Mn = 1.20–1.28) having multiple copies of d-mannose epitopes have been obtained following two independent synthetic pathways that involve a combination of copper-catalyzed living radical polymerization and alkyne–azide [2+3] cycloaddition (“click”). These coupled with model thiol-containing protein BSA and the resulting bioconjugates were first purified following two independent purification protocols and then characterized by SEC HPLC, SDS PAGE, and CD analysis. These biohybrid materials appear to be particularly intriguing as they could potentially combine features proper of their protein component, such as enzymatic activity, ligand affinity, or the ability of acting as source of specific aminoacid sequences, with lectin binding properties, with consequent engagement with the counter-glycome in plasma, cells, and tissues, typical of its neoglycopolymer component. The versatility of the approach was further demonstrated by preparing a library of BSA–neoglycopolymer hybrid materials featuring different relative amounts of d-mannose and d-galactose binding epitopes following a coclicking approach.

Surface plasmon resonance (BIAcore) tests carried out in the presence of the model mammalian lectin, recombinant rat mannose-binding lectin (MBL), revealed a significant and dose-dependent binding of the latter to the BSA–neoglycopolymer conjugates. ELISA tests also revealed that our biohybrid materials were also able to activate the complement system via the lectin pathway.

In summary, through a simple and efficient conjugation step, a non-glycosylated model protein, BSA, has been site-specifically modified with a mannoside neoglycopolymer leading to a substantial addition of function with regard to engagement of a critical arm of mammalian innate immunity. This indicates the principle of how proteins can be effectively modified with neoglycopolymers in a highly defined fashion, providing a gateway for rapid, diverse, and cost-effective neoglycoprotein developments–a phenomenon that could have profound value in the deconvolution and exploitation of the functional glycome in a broad range of biological species.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the Glycoprotein Mimic Employed in This Study

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the University of Warwick (J.G. and L.T.) for funding. D.A.M. is a Research Councils UK Academic Fellow with additional support from the Warwick Research Development Fund. R.W. is a Research Councils Academic Fellow and supported by grant 077400 from the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Gianfranco de Pascale and Rajan Kumar Randev are also thanked for their help in the FPLC purification of the conjugates and providing an analytically pure sample of p-nitrophenol acetate.

Footnotes

Note Added after ASAP Publication: There was a production error in the version published on the Internet on November 17, 2007. In the print version and in the version published on the Internet on November 19, 2007, the correct version of Scheme 4 is present.

Supporting Information Available: Experimental section, including characterization of maleimide polymers and all intermediates, bioconjugation experiments, and in vitro test procedures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Rademacher TW, Parekh RB, Dwek RA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1988;57:785–838. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varki A. Glycobiology. 1993;3(2):97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dwek RA. Chem. Rev. 1996;96(2):683–720. doi: 10.1021/cr940283b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dove A. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19(10):913–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertozzi CR, Kiessling LL. Science. 2001;291(5512):2357–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1059820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiessling LL, Cairo CW. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20(3):234–235. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tirrell DA. Nature. 2004;430(7002):837. doi: 10.1038/430837a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Middel J, Cornelissen IL, Nottet HS, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y. Cell. 2000;100(5):587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy R, Laferriere CA, Pon RA, Gamian A. Methods Enzymol. 1994;247:351–61. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)47026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tropper FD, Romanowska A, Roy R. Methods Enzymol. 1994;242:257–71. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)42026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Q, Dordick JS, Linhardt RJ. Chem. Mater. 2002;14(8):3232–3244. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Ladmiral V, Melia E, Haddleton DM. Eur. Polym. J. 2004;40(3):431–449. [Google Scholar]; (b) Myura Y. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2007;45(22):5031–5036. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambrosi M, Cameron NR, Davis BG. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3(9):1593–1608. doi: 10.1039/b414350g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mammen M, Chio S-K, Whitesides GM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37(20):2755–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45(15):2348–2368. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuster MM, Esko JD. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5(7):526–542. doi: 10.1038/nrc1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortell KH, Weatherman RV, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118(9):2297–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi S-K, Mammen M, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119(18):4103–4111. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuster MC, Mortell KH, Hegeman AD, Kiessling LL. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1997;116(1–2):209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manning DD, Hu X, Beck P, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119(13):3161–3162. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanai M, Mortell KH, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119(41):9931–9932. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann DA, Kanai M, Maly DJ, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120(41):10575–10582. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strong LE, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121(26):6193–6196. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gestwicki JE, Strong LE, Kiessling LL. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39(24):4567–4570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gestwicki JE, Cairo CW, Strong LE, Oetjen KA, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(50):14922–14933. doi: 10.1021/ja027184x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cairo CW, Gestwicki JE, Kanai M, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(8):1615–1619. doi: 10.1021/ja016727k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pontrello JK, Allen MJ, Underbakke ES, Kiessling LL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127(42):14536–14537. doi: 10.1021/ja053931p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladmiral V, Mantovani G, Clarkson GJ, Cauet S, Irwin JL, Haddleton DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128(14):4823–4830. doi: 10.1021/ja058364k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon EJ, Sanders WJ, Kiessling LL. Nature. 1998;392(6671):30–31. doi: 10.1038/32073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders WJ, Gordon EJ, Dwir O, Beck PJ, Alon R, Kiessling LL. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(9):5271–5278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2000;4(6):696–703. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gestwicki JE, Strong LE, Borchardt SL, Cairo CW, Schnoes AM, Kiessling LL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9(9):2387–2393. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gestwicki JE, Kiessling LL. Nature. 2002;415(6867):81–84. doi: 10.1038/415081a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamanna AC, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE, Borchardt SL, Owen RM, Kiessling LL. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184(18):4981–4987. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.4981-4987.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato M, Kamigaito M, Sawamoto M, Higashimura T. Macromolecules. 1995;28(5):1721–1723. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J-S, Matyjaszewski K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117(20):5614–15. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamigaito M, Ando T, Sawamoto M. Chem. Rev. 2001;101(12):3689–3745. doi: 10.1021/cr9901182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matyjaszewski K, Xia J. Chem. Rev. 2001;101(9):2921–2990. doi: 10.1021/cr940534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiefari J, Chong YK, Ercole F, Krstina J, Jeffery J, Le TPT, Mayadunne RTA, Meijs GF, Moad CL, Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Macromolecules. 1998;31(16):5559–5562. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barner L, Barner-Kowollik C, Davis TP, Stenzel MH. Aust. J. Chem. 2004;57(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Aust. J. Chem. 2005;58(6):379–410. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrier S, Takolpuckdee P. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2005;43(22):5347–5393. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grande D, Baskaran S, Baskaran C, Gnanou Y, Chaikof EL. Macromolecules. 2000;33(4):1123–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grande D, Baskaran S, Chaikof EL. Macromolecules. 2001;34(6):1640–1646. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun X-L, Grande D, Baskaran S, Hanson SR, Chaikof EL. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3(5):1065–1070. doi: 10.1021/bm025561s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun X-L, Faucher KM, Houston M, Grande D, Chaikof EL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(25):7258–7259. doi: 10.1021/ja025788v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hou S, Sun X-L, Dong C-M, Chaikof EL. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15(5):954–959. doi: 10.1021/bc0499275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guan R, Sun X-L, Hou S, Wu P, Chaikof EL. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15(1):145–151. doi: 10.1021/bc034138t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun X-L, Stabler CL, Cazalis CS, Chaikof EL. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17(1):52–57. doi: 10.1021/bc0502311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faucher KM, Sun X-L, Chaikof EL. Langmuir. 2003;19(5):1664–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohno K, Tsujii Y, Fukuda T. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1998;36(14):2473–2481. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muthukrishnan S, Zhang M, Burkhardt M, Drechsler M, Mori H, Mueller AHE. Macromolecules. 2005;38(19):7926–7934. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta SS, Raja KS, Kaltgrad E, Strable E, Finn MG. Chem. Commun. 2005:4315–4317. doi: 10.1039/b502444g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ladmiral V, Monaghan L, Mantovani G, Haddleton DM. Polymer. 2005;46(19):8536–8545. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vazquez-Dorbatt V, Maynard HD. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(8):2297–2302. doi: 10.1021/bm060105f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lowe AB, Sumerlin BS, McCormick CL. Polymer. 2003;44(22):6761–6765. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albertin L, Kohlert C, Stenzel M, Foster LJR, Davis TP. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(2):255–260. doi: 10.1021/bm034199u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albertin L, Stenzel M, Barner-Kowollik C, Foster LJR, Davis TP. Macromolecules. 2004;37(20):7530–7537. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Albertin L, Stenzel MH, Barner-Kowollik C, Foster LJR, Davis TP. Macromolecules. 2005;38(22):9075–9084. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spain SG, Albertin L, Cameron NR. Chem. Commun. 2006:4198–4200. doi: 10.1039/b608383h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tornoe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67(9):3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. (Int. Ed.) 2002;41(14):2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40(11):2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Helms B, Mynar JL, Hawker CJ, Frechet JMJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126(46):15020–15021. doi: 10.1021/ja044744e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Devenish SRA, Hill JB, Blunt JW, Morris JC, Munro MHG. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47(17):2875–2878. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tao L, Mantovani G, Lecolley F, Haddleton DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126(41):13220–13221. doi: 10.1021/ja0456454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bontempo D, Heredia KL, Fish BA, Maynard HD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126(47):15372–15373. doi: 10.1021/ja045063m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mantovani G, Lecolley F, Tao L, Haddleton DM, Clerx J, Cornelissen JJLM, Velonia K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127(9):2966–2973. doi: 10.1021/ja0430999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bontempo D, Li RC, Ly T, Brubaker CE, Maynard HD. Chem. Commun. 2005:4702–4704. doi: 10.1039/b507912h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nicolas J, Khoshdel E, Haddleton DM. Chem. Commun. 2007:1722–1724. doi: 10.1039/b617596a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weis WI, Taylor ME, Drickamer K. Immunol. Rev. 1998;163:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neth O, Jack DL, Dodds AW, Holzel H, Klein NJ, Turner MW. Infect. Immun. 2000;68(2):688–693. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.688-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Turner MW. Mol. Immunol. 2003;40(7):423–429. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(03)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown KS, Ryder SD, Irving WL, Sim RB, Hickling TP. Immunol. Lett. 2007;108(1):34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walport MJ. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(14):1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walport MJ. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(15):1140–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nicolas J, San Miguel V, Mantovani G, Haddleton DM. Chem. Commun. 2006:4697–4699. doi: 10.1039/b609935a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kleinert M, Roeckendorf N, Lindhorst TK. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004;18:3931–3940. [Google Scholar]

- 79.To the best of our knowledge, two examples of direct conversion of d-mannose into its corresponding 2′-bromoethyl-glycoside have been previously reported: Smith EA, Thomas WD, Kiessling LL, Corn RM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(20):6140–6148. doi: 10.1021/ja034165u. (acid catalyst, camphorsulfonic acid). Mukhopadhyay B, Maurer SV, Rudolph N, Van Well RM, Russell DA, Field RA. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70(22):9059–9062. doi: 10.1021/jo051390g. (catalyst, HClO4 immobilized on silica)

- 80.Andre S, Unverzagt C, Kojima S, Dong X, Fink C, Kayser K, Gabius H-J. Bioconjugate Chem. 1997;8(6):845–855. doi: 10.1021/bc970164d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ellman GL. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959;82(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grassetti DR, Murray JF., Jr. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1967;119:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(67)90426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Riener CK, Kada G, Gruber HJ. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002;373(4–5):266–276. doi: 10.1007/s00216-002-1347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tildon JT, Ogilvie JW. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247(4):1265–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boyer C, Bulmus V, Liu J, Davis Thomas P, Stenzel Martina H, Barner-Kowollik CJ. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129(22):7145–7154. doi: 10.1021/ja070956a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu J, Bulmus V, Herlambang David L, Barner-Kowollik C, Stenzel Martina H, Davis Thomas P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46(17):3099–103. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.