Abstract

Objectives

We analyzed the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) database to determine whether suicidal events (attempts and ideation) occurred early in treatment, could be predicted by severity of depression or other clinical characteristics, and were preceded by clinical deterioration or symptoms of increased irritability, akathisia, sleep disruption, or mania.

Methods

TADS was a 36-week randomized controlled clinical trial of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments involving 439 youths with major depressive disorder. Suicidal events were defined according to the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicidal Assessment.

Results

Forty-four patients (10.0%) had at least one suicidal event (no suicide occurred). Events occurred 0.4–31.1 weeks (mean 11.9 ± 8.2) after starting TADS treatment, with no difference in event timing for patients receiving medication versus those not on medication. Severity of self-rated pre-treatment suicidal ideation (Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire for Adolescents score ≥ 31) and depressive symptoms (Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale score ≥91), predicted occurrence of suicidal events during treatment (p<0.05). Patients with suicidal event were on average still moderately ill prior to the event (Clinical Global Impression- severity score 4.0 ± 1.3), and only minimally improved (Clinical Global Impression- improvement score 3.2 ± 1.1). Events were not preceded by increased irritability, akathisia, sleep disturbance, or manic signs. Specific inter-personal stressors were identified in 73% of cases. Of the events, 55% resulted in overnight hospitalization.

Conclusions

Most suicidal events occurred in the context of persistent depression and insufficient improvement, without evidence of medication-induced behavioral activation as a precursor. Severity of self-rated suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms predicted emergence of suicidality during treatment. Risk for suicidal events did not decrease after the first month of treatment, suggesting the need for careful clinical monitoring for several months after starting treatment.

The presence of suicidal ideation or behavior is among the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, but it is neither necessary nor sufficient for the diagnosis.1 Nonetheless, suicidal behavior in strongly linked to depression in both adults and adolescents.2 Besides depression, history of previous suicidal attempts, presence of psychosis, alcohol or substance abuse, sleep disturbance, and comorbidity of depression with anxiety or disruptive behavior are psychiatric risk factors for suicidal behavior.2–4 In addition, demographic characteristics, such as gender and race/ethnicity, and contextual factors, such as family conflict, dysfunctional attitudes, and other environmental stressors contribute to the risk.2

Perhaps not surprisingly given the multifactorial origin of these phenomena, the relationship between suicidal behavior and depression remains poorly understood. No clinically useful predictors of developing suicidality during treatment are known for depressed adolescents who have no specific history of suicidal behavior. Moreover, while suicidal tendencies can stem from feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness or guilt, which are core symptoms of depression, it has been clinically observed that suicidality can also emerge when depression seems to lift and patients improve.5 The finding of an association between antidepressant treatment and increased rate of suicidal ideation and behavior in pediatric controlled clinical trials of antidepressants has added a further layer of complexity to the relationship among depression, its treatment, and suicidality.6,7

The mechanism through which antidepressant medication might increase suicidal ideation and behavior is unknown. It has been proposed that antidepressants may induce behavioral activation, including anxiety, irritability, agitation, and insomnia, which would facilitate suicidal ideation and behavior.8 If this were the case, one would expect that the incidence of suicidal events would be highest at the beginning of antidepressant treatment. Analyses of community clinical practice databases have indeed indicated that the rate of suicidal behavior is highest in the first month of treatment, and especially during the first nine days.9 In other analyses of health claim data, the rate was actually the highest in the month prior to starting antidepressant medication with a gradual decline during treatment.10,11

This pattern likely reflects the fact that, in usual practice, antidepressants are often started at a time of increasing depression and acute distress. If treatment is started during a crisis, it is not surprising that the suicide risk is highest before treatment and tends to decrease in time as the crisis resolves. In any case, current practice guidelines recommend that closed monitoring be paid by clinicians and family members to adolescents during the first few weeks of antidepressant treatment.12

The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) was a 36-week controlled clinical trial that included outpatients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder, but excluded youths considered at especially high risk for suicide due to recent history of suicidal behavior or prominent suicidal ideation, or with comorbid substance abuse or severe conduct disorder. The main outcomes of TADS have been reported,13–14 including also suicidal events by treatment and a detailed analysis of the first 12-week safety data.15 During the 36-week TADS treatment, 9.8% of the patients randomized to active treatment presented with a suicidal event. The rate was higher (p<0.05) in the fluoxetine (14.7%) than in the psychotherapy group (6.3%), which was not different from the combined treatment group (8.4%), while the combined treatment and fluoxetine groups did not significantly differ from each other.14

For this report, we analyzed the TADS database to address the following five questions. First, was the rate of suicidal events highest in the first few weeks of treatment? Based on previous population epidemiological data, it was expected that peak incidence would occur within the first 3–4 weeks of treatment. Second, could pretreatment clinical characteristics predict emergence of suicidal event during treatment? Specifically, it was hypothesized that severity of depression, comorbid anxiety, and suicidal ideation at treatment entry would be associated with greater risk for suicidal events during treatment. Third, what was the clinical status of the youths with suicidal behavior proximally to the event? Based on the known link between depression and suicidal behavior, it was predicted that most suicidal patients would still be depressed and not improved. Fourth, did the youths with a suicidal event present signs of behavioral activation prior to the event? We hypothesized that a substantial number of suicidal youths would present symptoms of behavioral activation in the two weeks prior to event, and that this association with behavioral activation would be specifically present if the patient was receiving antidepressant medication. Fifth, what were the most common consequences of a suicidal event with respect to patient disposition and treatment? It was expected that most events would lead to emergency room visits or overnight hospitalization.

Methods

TADS

TADS was a publicly funded, randomized clinical trial to evaluate the acute (12 weeks) and long-term (36 weeks) effectiveness of fluoxetine (FLX), cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), and their combination (COMB) in the treatment of adolescents with major depressive disorder.13,14,16 A placebo condition was included as a control for the first 12 weeks, after which all treatments were unblinded. Patients who were deemed responders or partial responders, as documented by a score of minimally improved or better on the Clinical Global Impression- Improvement scale (CGI-I),17 continued with their assigned treatment up to the end of the 36-week trial. Non-responders were discontinued from study treatment and managed as clinically indicated while still participating in the remaining assessments throughout week 36.

The TADS sample consisted of 439 adolescents, age 12–17 years (mean 14.6 ± SD 1.5; 206 age 12–14 years and 233 age 15–17 years), 54% females, 74% Caucasian, meeting criteria for major depressive disorder. For 86% of the participants, it was the first episode of major depression, whose median duration was 40 weeks.13 Most patients had a comorbid condition, most frequently an anxiety (27%), disruptive behavior (23%) or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (14%). Exclusion criteria included: current substance abuse or dependence, severe conduct disorder, thought disorders, bipolar disorder, suicidal attempt requiring medical attention within past 6 months, clear intent or active plan to commit suicide, suicidal ideation with family disorganization, or being clinically deemed to be at “high-risk” for self-injurious or aggressive acts.13

Assessments

Suicidal events

Adverse events were reported by patients and their parents to the treating clinicians at each study visit, which included self-report ratings of depressive symptoms, including suicidal behavior. After completion of the study, known or potential suicidal events were identified with electronic and manual searches according to the same methods used for the FDA meta-analyses.6,18 Description of the events were then reviewed by independent experts at Columbia University and coded according to the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicidal Assessment (C-CASA).18 Suicidal events consisted of discrete episodes of suicidal ideation, suicidal attempts, or preparatory acts toward an imminent attempt. Harmful self-injurious acts without an expressed or inferred suicidal intent were not included.

Suicidal Ideation

Suicidal ideation was systematically assessed with the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire adapted for adolescents (SIQ-Jr), a 15-item patient-rated instrument, administered before starting treatment and every 6 weeks afterwards.13,14, 19 A total score above 31 is indicative of elevated suicidal risk (“suicidal flag”). Another index of suicidal risk was the item 3 of the clinician-rated Child Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), with a score of 1 or 2 indicating no suicidal ideation, a score of 3 indicating some suicidal thinking and/or behavior, and a score of 4 or higher indicating significant concern about suicidality due to presence of persistent or recurrent ideation and/or behavior.20

In addition, the Adolescent Depression Scale (ADS), a 31-item Likert rating scale of DSM-IV depressive and related symptoms, was completed by the study clinician based on information elicited from the patient at each visit.15 On this scale, each item is rated from 0 (not present) to 3 (severe). A principal component analysis, with varimax rotation, of the ADS data from TADS identified five factors, including depression, mania, attention, appetite, and suicidality. The ADS depression score was correlated with the CDRS-R score at baseline (r=.42. p<0.0001, n=384). Because the ADS was administered more frequently than the CDRS-R or the SIQ-Jr, it was used in these analyses to assess the clinical status of the patient immediately prior to the suicidal event.

Severity of Illness, Psychopathology, and Improvement

Severity of illness was assessed with the Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S),17 which was completed by the study clinician at study entry and at each treatment visit. Severity of depressive psychopathology was assessed with the clinician-rated CDRS-R, with a total score of 60 or above at study entry was taken as an index of severe depression. The CDRS-R items of irritability and sleep disturbance, and the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS)21 at baseline were also examined as possible predictors of suicidal events during treatment. In addition, a score above 90 on the patient self-rated Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS) was considered an index of severe depression. 22

Presence and history of comorbid attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional/defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), or substance abuse were assessed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Present and Lifetime version, which was administered at baseline before starting treatment.23 Anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC).24

Improvement compared with status at study entry was measured with the CGI-I and change in the ADS, which were completed by the clinician at each visit. Clinical status prior to the event was measured by the most proximal rating available before the event occurrence, and in any case no more than 2 weeks prior to the event.

Behavioral activation

The ADS items of mania, irritability, and sleep disturbance within the 2 weeks prior to the suicidal event, and their change from baseline scores, were used to assess whether the event was preceded by signs suggesting behavioral activation. In addition, the adverse event database was searched for reports of akathisia, agitation, mania, sleep disturbances, irritability or aggression during the 2 weeks prior to suicidal events.

Interpersonal Stressors

The Family Assessment Measure-III General Scale overall T score and the Children’s Conflict Behavior Questionnaire,25,26 independently completed by parent and adolescent at baseline, served as a measure of reported family conflict. The individual descriptors of the suicidal events were manually searched for any record of environmental stressors immediately prior to the event.

For each suicidal event that occurred during TADS, the reports of the clinicians describing the events were reviewed and possible presence of interpersonal conflict immediately preceding the event was noted.

Data analyses

Unit of analysis was the patient. Descriptive statistics were applied and associations were tested using non-parametric tests such as chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at a conventional p=0.05 with no attempt to control for multiple testing given the exploratory intent of these analyses. For patients with more than one suicidal event, the suicidal event of greatest severity (e.g., suicidal attempt as compared with suicidal ideation) was included in most analyses. The exception was that the first suicidal event was included in the analyses examining time to first event and clinical changes prior to first event. For each significant predictor variable identified, a receiver operator curve (ROC) was plotted in order to examine visually the relationship between sensitivity and sensitivity as a function of the cut-off used.

Results

Incidence and Timing of Suicidal Events

During the 36 weeks of TADS, 44 adolescents (10% of the entire sample) presented with at least one suicidal event, of which 23 consisted of suicidal ideation and 21 of suicidal attempts (Table 1). There were no suicides. Incidence did not differ by gender (9.6% in females vs. 10.5% in males), race/ethnicity (9.9% in Caucasian vs. 10.4% in other racial/ethnic groups), or age (10.7% among 12–14 year-olds vs. 9.4% among 15–17 year-olds).

Table 1.

Suicidal Event Categoriesa

| Randomized Treatment Assignmentb | N | Suicidal Ideation (code 6) | Suicide Attemptc (code 1 or 2) | Total (code 1, 2, or 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMB | 107 | 5 (4.7%) | 4 (3.7%) | 9 (8.4%) |

| FLX | 109 | 9 (8.3% | 7 (6.4%) | 16 (14.7%)d |

| CBT | 111 | 3 (2.7%) | 4 (3.6%) | 7 (6.3%) |

| PBO | 112 | 6 (5.4%) | 6 (5.4%) | 12 (10.7%) |

| Total: 4 arms | 439 | 23 (5.2%) | 21 (4.8%) | 44 (10.0%) |

Numbers are patients with at least one event with code 1, 2, or 6 on the C-CASA (Posner et al. 2007). For patients with two events (N=7), only the more severe event was included in this table.

FLX: fluoxetine monotherapy; CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; COMB: combination of FLX and CBT. Treatment at time of event was different from the randomized one for 3 CBT and 9 PBO patients, who had started antidepressant medication due to poor response to assigned treatment.

Including also one episode of preparatory act towards imminent suicidal attempt (code 2).

Higher than in CBT (p=0.04) or PBO (p=0.02), when considering only the CBT and PBO patients who were not on medication at time of the event (Fisher’s exact test).

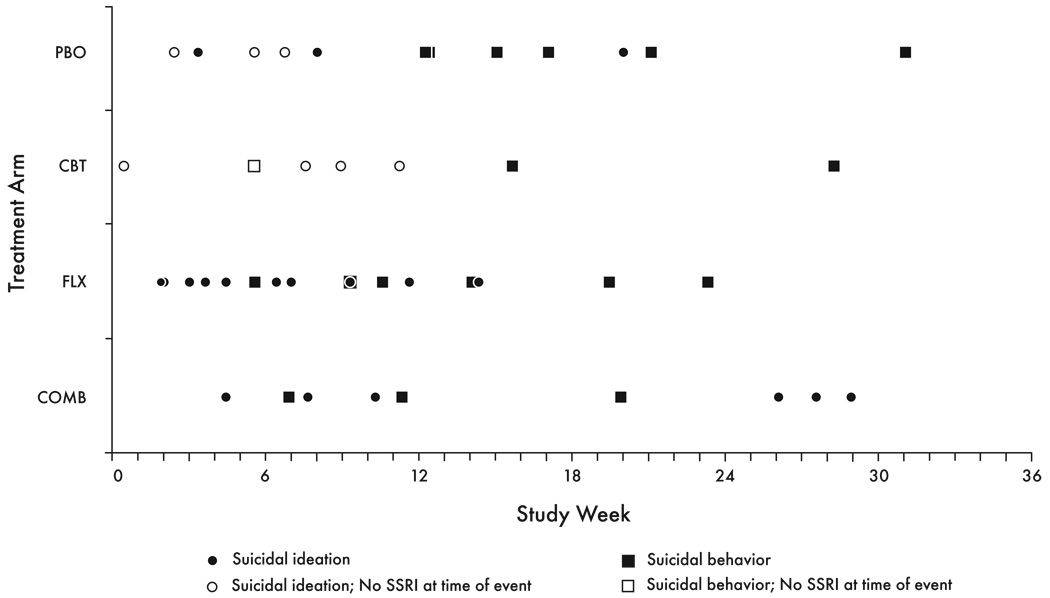

The time from entering treatment to occurrence of suicidal event ranged from 0.4 to 31.1 weeks (mean 11.9 ± SD 8.2 weeks), with no differences among the four treatment arms (COMB: 15.9 ± 9.7; FLX: 9.1 ± 23.3; CBT: 11.1 ± 8.9; PBO: 12.9 ± 8.2; Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2=3.5, p=0.31). Suicidal events occurred as early as a few days after entering treatment, and were not less frequent in the second month of treatment as compared with the first one. In particular, none of the 21suicidal attempts occurred in the first 4 weeks (Fig.1). No suicidal events occurred in the last month of the 9-month treatment.

Figure 1.

Timing of First Suicidal Event (N=44)

Some patients who had been randomized to CBT (N=2) or PBO (N=9) and had a suicidal event were in fact on SSRI medication at the time for the event having started antidepressant treatment because of non-response to the randomly assigned treatment. For these patients, time to event was recomputed by taking the time when SSRI medication was initiated as the starting point. Using this approach, for all the patients on SSRI at time of the event (N=36), the time to event was 10.0 ± 7.7 weeks (range 0.7–28.9), which was not statistically different from that for the patients not on antidepressant medication at the time of the event (N=8; 5.8 ± 3.2 weeks, range: 0.4–10.4; Wilcoxon two-sample test, z=−1.2, p=0.22).

Searching for Predictors of Suicidal Events

An SIQ-Jr score of 31 or greater at baseline was significantly associated with emergence of a suicidal event during treatment. Of the 125 patients with baseline suicide risk flag >30, 15.2% had a suicidal event as compared with 8.3% of the 303 patients without a flag (χ2=4.6; p=0.03, OR=2.0, 95% CI 1.1–3.8). With 31 as a cutoff, the sensitivity was 43% and specificity 72%. The ROC had an area under the curve of 63.7% and indicated that, if a cutoff score of 21 were to be used instead of 31, the sensitivity would be 64% and specificity 60%.

A RADS score above 90 at baseline was also associated with emergence of a suicidal event during treatment. Of the 94 patients with baseline score above 90, 16.0% had a suicidal event as compared with 8.7% of those with a lower score (χ2=4.2; p=0.04, OR=2.0, 95% CI 1.0–3.9). The ROC had an area under the curve of 56.0% and confirmed that a cutoff above 90 offered the best balance between sensitivity (34%) and specificity (79%).

No association was found between suicidal events and the other tested clinical characteristics, including baseline severity of depression (CDRS-R total score, CGI-S), severity of specific depressive symptoms (CDRS-R suicidal ideation, irritability, and sleep disturbance), hopelessness (BHS), anxiety symptoms (MASC), comorbidity with ADHD, ODD, or CD, family conflict, or history of substance abuse.

Clinical Status in the Two Weeks Prior to the Suicidal Event

For 31 of the 44 patients with suicidal events, proximal (i.e., within two weeks prior to the event) scores of severity of illness, improvement status, depression, irritability, mania, and sleep disturbances were available (Table 2). Even if depression symptoms had decreased compared with the beginning of treatment, most of these patients were still at least moderately depressed and unimproved. Based on the CGI-I, 33.3% were unchanged, 33.3% were minimally improved, 26.7% were very much or much improved, and 6.6% were worse. There was no evidence of an increase of irritability, mania, or sleep problems. A systematic search of the adverse event database for possible reports of symptoms suggestive of behavioral activation found that only in one case the patient had insomnia, mood lability, and irritability in the two weeks prior to the suicidal event.

Table 2.

Clinical Status Prior to the Suicidal Event vs. Starting Treatment

| Na | At First Treatment Visit mean + SD | Prior to Eventb mean + SD | Changec mean + SD | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGI-Sd | 31 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | −0.8 ± 1.2 | 22 (74.0%) with score ≥4 prior to event. |

| CGI-Ie | 30 | Not applicable | 3.2 ± 1.1 | Not applicable | 22 (73.2%) with score ≥3 prior to event. |

| ADSf | |||||

| Depression | 31 | 21.0 ± 7.7 | 13.3 ± 8.5 | −8.1 ± 9.3 | |

| Irritability | 31 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | −0.3 ± 1.3 | |

| Mania | 31 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 1.6 ± 2.2 | −0.6 ± 2.3 | |

| Insomnia | 31 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | −0.4 ± 1.3 |

A total of 44 patients had an event. N indicates patients for whom data were available.

The data most proximal to the event were included, and in any case within the 2 weeks prior to the event.

Score prior to event minus score at first treatment visit.

CGI-S: Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness; 1=normal; 2=borderline ill; 3=mildly ill; 4=moderately ill; 5=markedly ill; 6=severely ill; 7=extremely ill.

CGI-I: Clinical Global Impression-Improvement; 1=very much improved; 2=much improved; 3=minimally improved; 4=no change; 5=minimally worse; 6=much worse; 7=very much worse.

ADS: Adolescent Depression Scale. Depression score included 19 items, with possible range 0-57. The mania score included 9 items, with possible range 0–27. Irritability and insomnia included one item each with possible range 0–3.

For 72.7% of the 44 patients with a suicidal event, an acute interpersonal conflict (youth-parent conflict in 84% and youth-peer conflict in 16% of the cases) was identified. In addition, 13% of the patients with suicidal event had some identifiable recent legal problem. However, measures of family stressors or parent-child conflict at baseline were not significant predictors of suicidal events during TADS.

Disposition after Suicidal Events

Of the 44 patients experiencing a suicidal event, 24 (55%) were hospitalized for a period ranging from 1 to 9 days. Six others (14%) had only a hospital emergency room visit without inpatient hospitalization, while 14 (22%) had neither.

Discussion

Previous publications have reported on the increased incidence of suicidal events observed in TADS among youths randomized to fluoxetine monotherapy and the protective effect of CBT when combined to fluoxetine in decreasing suicidal risk.13–15 In this report, we present analyses of the timing of suicidal events and the possible associations between suicidal events and clinical characteristics at study entry or proximally to the event. The purpose was to identify possible predictors and immediate antecedents of suicidal behavior in depressed adolescents entering treatment without more specific risk factors for suicide. In fact, TADS participants were outpatients who were not abusing drugs or alcohol, had no psychotic or manic symptoms, nor history of recent suicidal attempts or suicidal threats, and were not in acute crisis at study entry. One particular aim was to search for possible indicators of an antidepressant-induced behavioral activation syndrome preceding the suicidal event. If the increased rate of suicidal events observed on antidepressants were mediated by behavioral activation, one would expect suicidal events to occur in the initial period after starting medication and to be preceded by increase in irritability, mood instability, insomnia, and akathisia.

We found that time to suicidal event was variable, occurring as early as the first week and as late as 6 months after starting treatment, and that it was not shorter for patients treated with antidepressant medications than those off medication. Overall, the rate of suicidal events was not higher in the first month of treatment than in the subsequent two months. Furthermore, there was no evidence of increased irritability, insomnia, or agitation in the two weeks prior to the event. Thus, these data do not support the hypothesis of medication-induced behavioral activation as a trigger for suicidal behavior during SSRI treatment. It must be observed, however, that TADS did not use a rapid dose escalation and that the starting dose was only 10 mg/day.

Although depressive symptoms had declined since entering treatment, most patients who become suicidal were still depressed at the time of the suicidal event, had not achieved a clinically adequate level of improvement, and reported some acute inter-personal stressor just before the event. These findings indicate that suicidal events during treatment occurred in a context of persistent depression, insufficient improvement, and an acute inter-personal conflict. In addition, the data indicate that suicidal events, even if not resulting in physical harm, often led to hospitalization and consequently had substantial cost implications.

The results also confirm the difficulty of predicting with any precision the emergence of suicidal behavior among clinically depressed patients. Even though pretreatment indexes of self-reported suicidal ideation (SIQ-Jr) and depressive symptomatology (RADS) were statistically associated with presenting with suicidal events during treatment, both the sensitivity and specificity of these instruments are suboptimal for diagnostic purposes, as also shown by ROC areas under the curve below 0.70 (accuracy is considered excellent if AUC is 0.90–1.0, good if 0.80– 0.90, fair if 0.70–0.80, and poor if 0.60–0.70). In any case, these data suggest that self-rated instruments of suicidality and depression are more sensitive in detecting suicidal risk than rating scales scored by the clinician (i.e., CDRS-R). This finding is consistent with another study in adolescent depression.27 Thus, youths appears more likely to indicate clinically relevant suicidal ideation when completing an assessment questionnaire themselves rather than to share these thoughts in a directly interview with a clinician.

Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Despite being one of the largest controlled clinical trials in adolescent depression, TADS is still rather small in sample size to allow adequate exploration of predictors and moderators of treatment. In fact, the power to detect predictors with a two-tail alpha of 0.05 was only about 30% or less (according to the variable being tested). Because of this low power, we cannot rule out false negative findings. Furthermore, the TADS was designed in 1999 and conducted before attention was brought to suicidality in antidepressant treatment in 2003 and subsequent years. The adverse event data were collected based on spontaneous patient report rather than systematically elicited by the investigators. This limitation is in part attenuated by the systematic administration of rating scales that included suicidal ideation and other relevant symptoms. Another limitation is that the baseline assessment, although quite detailed, did not include a number of variables potentially relevant to suicidal behavior, such as family history of suicide. Finally, consistent with the TADS inclusion and exclusion criteria, the results of these analyses are limited to depressed youths who entered treatment while not being at high risk for suicide due to recent suicidal behavior, substance abuse, or stressful circumstances.

In conclusion, depressed adolescents who manifest suicidal ideation at treatment entry are at increased risk for suicidal events during treatment. The risk for suicidal events does not seem to decrease after the first month of treatment, suggesting the need for maintaining close monitoring for several months after starting treatment. Most depressed adolescents presenting with suicidal events during treatment are still significantly depressed, with no or minimal signs of improvement, and without evidence of drug-associated behavioral activation.

Acknowledgments

TADS was supported by contract N01 MH80008 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Duke University Medical Center.

The opinions and assertions contained in this publication are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure:

Susan Silva is a consultant with Pfizer. Christopher Kratochvil receives research support from Eli Lilly, Somerset, Abbott, Shire, McNeil, and Cephalon, is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Cephalon, AstraZeneca, Organon, and Shire, and is on the Speaker’s Bureau of Eli Lilly. Dr. Posner has been consultant and/or received research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Forest, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Johnson&Johnson, Abbott, Wyeth, Organon, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, Cephalon, Novartis, Shire, and UCB Pharma. John March is a consultant or scientific advisor to Pfizer, Lilly, Wyeth, GSK, Jazz, and MedAvante and holds stock in MedAvante; he receives research support from Lilly and study drug for an NIMH-funded study from Lilly and Pfizer. The other authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foley DL, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, Angold A. Proximal psychiatric risk factors for suicidality in youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1017–1024. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:84–91. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruenberg AM, Goldstein RD. Mood disorders: depression. In: Rasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, editors. Psychiatry. 2nd Edition. Vol. 2. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. pp. 1207–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:332–339. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, Ren L, Brent DA. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683–1696. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman WK, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Risk of adverse behavioral effects with pediatric use of antidepressants. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jick H, Kaye JA, Jick SS. Antidepressants and the risk of suicidal behavior. JAMA. 2004;292:338–343. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon GE, Savarino J, Operskalski B, Wang PS. Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:41–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon GE, Savarino J. Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medications or psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1029–1034. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.TADS Team: Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. JAMA. 2004;292:807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TADS Team: The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emslie GJ, Kratochvil CJ, Vitiello B, Silva SG, Mayes TL, McNulty S, Weller E, Waslick B, Casat C, Walkup J, Pathak S, Rohde P, March J. Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): safety results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1440–1455. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240840.63737.1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team: The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): demographics and clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:28–40. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145807.09027.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for the Psychopharmacology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Dept. of Health and Human Services Publication No. (ADM); 1976. pp. 91–338. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicidal Assessment (C-CASA) Classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds WM. Professional Manual for the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Manual for the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised. Los Angeles, LA: Western Psychological Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AT. Beck Hopelessness Scale. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynolds WM. Professional Manual for Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale. Odessa, FL: The Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skinner H, Steinhauer P, Sitarenios G. Family Assessment Measure (FAM) and Process Model of Family Functioning. J Family Therapy. 2000;22:190–210. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robin AL, Foster SL. Negotiating Parent Adolescent Conflict: A Behavioral Family Support System Approach. New York: Guilford; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bridge JA, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Kolko DJ, Brent DA. Emergent suicidality in a clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2173–2175. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]