Abstract

Background

The financial reimbursement for breast reconstruction is perceived to be low. We evaluated the financial impact of providing breast reconstruction for an academic medical practice and health care system.

Study Design

We examined the billing records for 97 patients receiving post-mastectomy breast reconstruction in 2006 at the University of Michigan. Professional net revenue was calculated by applying actual collection rates to procedural charges. Facility revenue was calculated by applying actual collection rates to charges from inpatient care and the operating room.

Results

The payer mix was 70.1% private insurance, 22.7% HMO, 3.1% Medicare, 2.1% Medicaid, and 2.0% uninsured. The professional revenue and costs allocated to breast reconstruction was $242,078 and $177,411, respectively, (net profit of $64,667 (27%)). Health system facility revenue and costs were $1,109,678 and $943,892, respectively, (net profit of $165,786 (15%)). Physician reimbursement by surgical time was highest for delayed tissue expander placement ($1,977.70/hour in OR) and lowest for immediate TRAM flaps ($327/hr in OR). The facility received the greatest average direct margin on TRAM flaps ($3,471) and lost money on latissimus dorsi flaps (− $398 margin).

Conclusions

Post-mastectomy breast reconstruction at this academic medical center is fiscally advantageous for both the surgical department and the healthcare system. However, reimbursement varies dramatically by type and timing of reconstructive procedure. Although immediate post-mastectomy reconstructions with TRAM flaps provide superior aesthetic results with the greatest amount of patient satisfaction, poor physician reimbursement for these labor-intensive procedures may limit surgeons’ ability to provide these services due to poor financial return.

Keywords: Healthcare Finances, Breast Cancer, Post-Mastectomy Reconstruction, Breast Reconstruction, outcomes

National health policy leaders, physicians and breast cancer advocates have been concerned about the under-utilization of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction.(1) As a result, Congress passed the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act in 1998 that mandated insurance coverage of these procedures.(2) However, the law had little effect. Rates for immediate breast reconstruction have remained low, and racial and geographical variations have persisted.(3, 4)

Potential reasons for under-use include an increase in the uninsured population,(5) limited referrals for post-mastectomy reconstruction(6) and reconstructive surgery workforce shortages.(7) A large barrier to reconstructive surgery involves the growth of the uninsured population, which reached a record high of 46.6 million Americans in 2005.(8) Often these patients may become eligible for Medicaid, but many physicians are reluctant to accept this third party payer due to poor reimbursement.(9) Compounding this problem are physicians’ concerns about declining reimbursement.(10) Surgical specialists, compared to primary care physicians, are overly burdened to provide charity care for emergency on-call responsibilities (11) and cancer care.(12) However, declining insurance reimbursement for elective surgery is making reconstructive surgery and charity care financially more burdensome.

To examine these issues, we evaluated the financial aspects of providing reconstructive services for the post-mastectomy breast cancer population at a single academic institution. Our purpose was to 1) study the overall financial impact of this patient group on both the academic surgical department and the healthcare institution; 2) evaluate the impact of procedure type and timing on reimbursement; and 3) evaluate trends in reimbursement over the past decade

Methods

Study Sample

We examined the inpatient billing records of all breast cancer patients who underwent post-mastectomy breast reconstruction at the University of Michigan Health System for the 2006 fiscal billing year (N=97). All patients had 1 of 12 primary diagnosis ICD-9 codes for breast cancer and received an immediate or delayed unilateral or bilateral pedicle transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap, latissimus dorsi flap, or tissue expander. The plastic surgery faculty consists of two full-time breast reconstructive surgeons who have, on average, two operative days per week and one clinic day per week. The remainder of their clinical week is protected for research and education. We also have an integrated plastic surgery training program, and therefore, residents are involved in patient care. However, the financial implications of resident education were not included in the analyses. Recorded data include plastic surgery professional charge, facilities (hospital) charge, attending surgeon name, and ICD-9 and CPT codes. All of the cases were performed at the University inpatient hospital. All professional and facility revenue and costs generated from inpatient operative procedures were included. We also included all inpatient revenue and costs. Non-operative outpatient professional and facility revenue and costs--such as those involving the clinic and occupational therapy-- were excluded due to incomplete data. Institutional review board approval was not required because the data were reported in aggregate without personal identifying information.

Calculation of Professional Costs, Revenues and Income

Professional revenue was defined as dollars received by healthcare providers in the Section of Plastic Surgery. The actual collection rate of 32.2% for 2006 was applied. Professional costs were defined as expenses incurred by the surgeons in our Section of Plastic Surgery by providing reconstructive services (TRAM flap, latissimus flap or tissue expander) to the post-mastectomy breast cancer population. The proportion of each physician’s salary, benefits and malpractice allocated to post-mastectomy breast reconstruction was based on that physician’s total revenue generated from post-mastectomy breast reconstruction divided by total gross charges on all operative cases (breast and non-breast cases). Professional costs also included internal department and health system taxes, which was 10.7% of professional net revenue.

Calculation of Facility Costs, Revenues and Earnings

Facility revenue was calculated by applying the actual collection rate of 56.0% from the post-mastectomy reconstruction cases included in the study to the following downstream charge categories: inpatient/OR (included nursing, anesthesia), clinic, and pharmacy. Hospital costs were provided by the hospital finance department using the health system’s cost accounting services, TSI (Eclypsis Inc., Newton, MA). The TSI system allocated variable direct costs, fixed costs and indirect costs (allocated overhead) to the billing system, payroll system and general ledger for each patient. Variable costs included those supplies consumed by the individual patient. Fixed costs reflected items that are permanent and can not be avoided by caring for fewer patients. Indirect costs, such as the health system administrators’ salaries, were real costs associated with running the health system but were difficult to assign to individual patients.

Calculation of Professional and Facility Earnings

Operating income (earnings) was defined as net revenues minus expenses. The operating margin was calculated by dividing operating income by net revenue. These calculations were performed for the professional activity (procedure charges) and the facility activity (inpatient/OR, clinic, and pharmacy). These calculations were based on the actual, not historical, professional and facility collection rates for fiscal year 2006.

Calculation of Professional Reimbursement by Operating Room Utilization

Operating room utilization was defined as the total time that the operating room was used for an individual patient. For an immediate reconstruction, operating room utilization would include the time required for the mastectomy by the general surgeon. We calculated the average time of operating room utilization for each breast reconstructive procedure performed by the two plastic surgeons that perform post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Reimbursement per operating room hour was then calculated by dividing the average procedure reimbursement by the average operating room time.

Results

The payer mix for this patient sample was 70.1% private insurance, 22.6% HMO, 3.1% Medicare, 2.1% Medicaid and 2.1% self-pay (Table 1). The highest professional and facility collection rate was from private insurance (40% and 63%, respectfully). Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) was the primary private third party payer in our region. The lowest professional collection rate was from the self-pay group (2% collection) followed by Medicaid (13% collection). The lowest facility collection rate was from Medicaid (20.4%). The procedure mix for the patient sample included 39.6% pedicle TRAM flaps, 16.3% latissimus dorsi flaps and 44.1% expander/implant procedures. 53.5% of the cases were performed at the time of the mastectomy; 46.5% were delayed post-mastectomy reconstructions.

Table 1.

Payer mix and collection rate for the study sample

| Type of Payer | Proportion of Sample | Professional Collection Rate | Facility Collection Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| Private | 70 | 40.0 | 63.4 |

| HMO | 23 | 30.0 | 54.0 |

| Medicare | 3 | 37.0 | 33.5 |

| Medicaid | 2 | 13.0 | 20.4 |

| Self-pay | 2 | 2.0 | 33.3 |

| Total collection rate | 32.2 | 56.0 | |

Table 2 displays the professional costs, revenue and earnings for the post-mastectomy reconstruction population. Net professional revenue was $242,078, total professional costs were $177,411, and net operating income was $64,667 (27% of net revenue). Table 3 displays the facility costs, revenue and earnings. The net facility revenue was $1,109,678, the net facility costs were $943,892, and the net operating income was $165,786 (15% of net revenue).

Table 2.

Professional costs, revenues and income

| Charges & Revenue | |

| Professional surgical charges | 750,105 |

| Less contractual adjustments | (508,027) |

| Total net professional revenue | 242,078 |

| Costs | |

| Physician salary, benefits and CME | 137,563 |

| Malpractice | 13,945 |

| Department & health system taxes (10.7% of professional net revenue) | 25,902 |

| Total professional expenses | 177,410 |

| Earnings-Professional perspective | |

| Net professional revenue | 242,078 |

| Net professional expenses | 177,411 |

| Operating Income | 64,667 |

| Operating income as % of net revenue | 27% |

Table 3.

Facility costs, revenues and earnings

| Charges & Revenue | |

| Facility inpatient care & operating room charges | 1,991,142 |

| Less contractual adjustments | (881,464) |

| Total net facility revenue | 1,109,678 |

| Costs | |

| Fixed expenses- inpatient care & operating room charges | 223,507 |

| Variable expenses- inpatient care & operating room charges | 416,631 |

| Indirect expenses- inpatient care & operating room charges | 303,755 |

| Total facility costs | 943,892 |

| Earnings-Facility perspective | |

| Total net facility revenue | 1,109,678 |

| Total facility expenses | 943,892 |

| Operating Income | 165,786 |

| Operating income as % of net revenue | 15% |

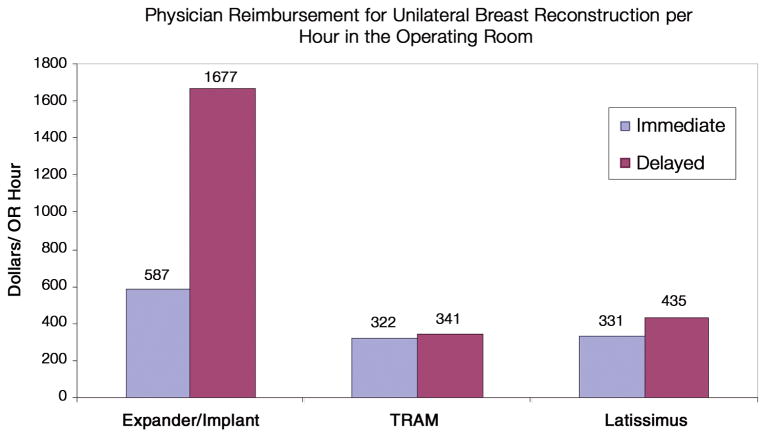

The average professional reimbursement per hour of operating room time for unilateral breast reconstructive procedures is displayed in Figure 1. The highest professional reimbursement for unilateral procedures per hour in the operating room was a delayed tissue expander ($1,677/hr), with the second highest being an immediate tissue expander ($587/hr). Autogenous tissue procedures ranged from $435/hr for a delayed latissimus flap to $322/hr for an immediate pedicle TRAM. Similar trends existed for bilateral procedures, with reimbursement per hour in the operating room the highest for a delayed bilateral tissue expander ($1,387/hr), with the second highest being an immediate bilateral tissue expander ($719/hr). Reimbursement for bilateral autogenous tissue reconstructions ranged from $428/hr for a delayed bilateral latissimus flap to $370/hr for an immediate bilateral pedicle TRAM flap.

Figure 1.

Physician Reimbursement for Unilateral Breast Reconstruction by Operating Room Time Utilization

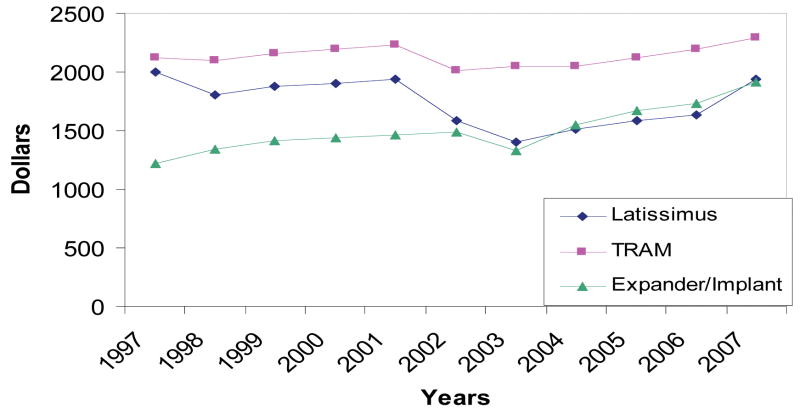

Reimbursement for breast reconstruction over the past 10 years from the largest payer in our region, Blue Cross Blue Shield, is displayed in Figure 2. BCBS reimbursement for a unilateral pedicle TRAM flap has remained relatively flat at $2,120 in 1997 and $2,297 in 2007. Reimbursement for a unilateral latissimus dorsi flap fell from $2,003 in 1997 to $1,404 in 2003 but had a slight gain ending at $ 1,939 in 2007. Expander/implant procedures have had a 64% increase in reimbursement over the past 10 years, from $1,224 in 1997 to $1,912 in 2007.

Figure 2.

Blue Cross/Blue Shield Physician Reimbursement for Unilateral Breast Reconstruction

Discussion

Despite a federal mandate for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction, the availability of reconstructive services is driven by market forces that take into account the profitability of the surgical procedures.(13) Because breast reconstruction is an elective procedure and not a life-threatening condition, the federal mandate cannot dictate whether patients will receive breast reconstruction. The labor intensive breast reconstructive procedures are perceived to be poorly remunerated, unless patients pay the “customary” charges of the surgeons. This study showed that a breast reconstruction program can be financially favorable for the academic health system and the academic professional practice. However, to generate this positive margin, this academic practice has a favorable reimbursement profile, marked by a low percentage of the lower paying insurance carriers.

We found that providing post-mastectomy breast reconstruction is fiscally advantageous for the surgical department (27% margin) and marginally fiscally advantageous for the healthcare institution (15% margin). Professional reimbursement by operating room utilization was highest for delayed tissue expander procedures, which require less operative time, and lowest for immediate or delayed autogenous tissue reconstructions. It appears that the more labor-intensive autogenous tissue procedures are under-valued despite their aesthetic advantages.(14, 15) Lastly, BCBS reimbursement for autogenous tissue procedures has not reflected the rise in inflation.

The Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act mandated insurance coverage of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction.(2) However, the federal law did nothing to ensure fair and equitable reimbursement for these procedures. The current outcomes data strongly suggests that patients are significantly more satisfied with autogenous tissue procedures compared to expander/implants.(14, 15) However, when one considers operative time by procedure type, surgeons are reimbursed almost four times more for an expander/implant compared to a flap procedure. And, with rising inflation, it will become financially more difficult for surgeons to offer complex autogenous tissue reconstructive procedures when reimbursement ranges from $331 to $435 per hour in the operating room.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. Our financial analyses were limited to the Section of Plastic Surgery at the University of Michigan Health Care System and may not be able to be generalized to other settings with different payer mixes, collection rates, procedure mixes, physician salary structures and operative times. For example, the allocation of indirect facility costs (such as the hospital building related to expenses, health system CEO salary, etc.) was based on the specific accounting system cost allocation assumptions used by our health system. Other institutions may have different accounting systems for indirect costs, especially on the facility side, and different efficiency models, which may affect net revenue. Furthermore, we do not account for geographical differences in revenue and costs.

These financial disincentives for breast reconstruction may be contributing to the low use of these procedures across the U.S.(3, 4) The continued observation that breast reconstruction after mastectomy is under-utilized in the US may be partially explained by this financial analysis. There are some data that suggest that free market forces impact healthcare utilization. For example, the rates of tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy significantly declined by 25% after a 30% reduction in Medicaid’s professional fees.(16) In breast cancer care, many general surgeons are expressing frustration that plastic surgeons are not accepting insurance reimbursement for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction.(6) This real or perceived disinterest in breast reconstruction by our society may be contributing to the rise of oncoplastic surgery by our general surgery colleagues.(17) Financial analysis and economic modeling will be an important research agenda in American medicine. With the declining resources available for healthcare in the US, healthcare institutions and physicians must make informed choices based on financial considerations and potential returns by relying on outcomes and quality of care indices.(18, 19) The creation of centers of excellence for breast reconstruction may be one method to improve efficiency and lower costs while strengthening negotiating power with third party payers.

These concerns are particularly germane to the breast reconstruction arena because according to the US National Cancer Institute, 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer during the course of their lifetime.(20) The need for reconstruction to restore self image for a woman after mastectomy should be an important concern for policy makers in allocating resources for specific high impact diseases. But these federal initiatives can not be instituted successfully unless financial considerations are part of decision- making processes. It is impractical for societies to demand breast reconstruction for all women when they are not willing to pay for it. Plastic surgeons who perform breast reconstruction will naturally base their decision to offer reconstruction, as well as the types of reconstruction, by considering the financial impact of these services. However, compared to other physicians, plastic surgeons are well-compensated. Given the current health of our economic environment, plastic surgeons must make individual decisions on what are acceptable reimbursements for these procedures, which definitely falls short of cosmetic procedures but may be more generous than other reconstructive services performed by other specialists.

Although this financial analysis is based on data from a large academic plastic surgery practice, the strategy used to derive these financial numbers can be useful for different practices in plastic surgery to evaluate their current margin for various types of breast reconstruction procedures. It also can be helpful to assist health policy-makers in allocating appropriate resources to assure that surgeons performing these procedures are not disadvantaged, when compared to hospitals that typically have a higher financial margin due to facility charges alone. If the institution is keen to offer breast reconstruction as part of its clinical offerings, it must remunerate surgeons appropriately if certain contracts are money losing ventures for the surgeons. If indeed autogenous breast reconstruction, including complicated microvascular reconstruction, gives the most optimal reconstruction in women, adequate payments from both the hospital and insurance companies must be given to the surgeons to reflect the added effort for these procedures. Otherwise, the number of women receiving breast reconstruction will continually decline, particularly those in the minority populations who have less financial means to receive these treatments. It would be most interesting to follow-up this study with national data to evaluate the large area variation of breast reconstruction in different regions of the country and varying reimbursement model. Improvement in the quality of healthcare will depend on strategies to minimize healthcare disparity, (21) while providing equitable and affordable treatments such as breast reconstruction.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Allison Pushman for her help in organizing this paper.

This project was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (to Dr Amy K. Alderman) and in part by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (to Dr Kevin C. Chung).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Horner-Taylor C. The Breast Reconstruction Advocacy Project: one woman can make a difference. Am J Surg. 1998;175:85–86. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [accessed June 8, 2005]; http://www3.cancer.gov/legis/dec01/womenshealth.html.

- 3.Alderman AK, McMahon L, Wilkins EG. The national utilization of immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction & the impact of sociodemographic factors. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;11:695–703. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041438.50018.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderman AK, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. Use of breast reconstruction after mastectomy following the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act. JAMA. 2006;295:387–388. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldfarb CA, Stern PJ. Metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:1869–1878. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Waljee J, et al. Correlates of referral practices of general surgeons to plastic surgeons for mastectomy reconstruction. Cancer. 2007;109:1715–1720. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Exodus of older physicians could create shortages. Phys Financial News. 2000 Aug;3 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas FL, Stukel TA, Morris AM, et al. Race and surgical mortality in the United States. Ann Surg. 2006;243:281–286. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197560.92456.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverstein G. Physicians’ perceptions of commercial and Medicaid managed care plans: a comparison. Journal of health politics, policy and law. 1997;22:5–21. doi: 10.1215/03616878-22-1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor TB. Threats to the health care safety net. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:1080–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung KC, Ram AN. Evidence-based medicine, the fourth revolution in American medicine? Plast Reconstr Surg. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181934742. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham P, May JH. A growing hole in the safety net: physican charity care declines again. Tracking report 13, Center for Studying Health System Change. 2006 March; Available at http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/2826/ [PubMed]

- 13.Ghori AK, Chung KC. Market concentration in the healthcare insurance industry has adverse repercussions on patients and physicians. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:435–440e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318170816a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alderman AK, Wilkins E, Lowery J, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction in post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2000;106:769–776. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200009040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alderman AK, Kuhn LE, Lowery JC, et al. Does patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction change over time? Two-year results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shwartz M, Martin SG, Cooper DD, et al. The effect of a thirty per cent reduction in physician fees on Medicaid surgery rates in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:370–375. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.4.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kollias J, Davies G, Bochner MA, et al. Clinical impact of oncoplastic surgery in a specialist breast practice. ANZ journal of surgery. 2008;78:269–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis Sears E, Burns PB, Chung KC. The outcomes of outcome studies in plastic surgery: a systematic review of 17 years of plastic surgery research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:2059–2065. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287385.91868.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung KC. Where do we find the best evidence? In: McCarthy C, Pussic A, Collins D, editors. Plast Reconstr Surg. Invited Commentary. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 20. [Accessed Aug 8, 2008]; http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html?statfacts_page=breast.html.

- 21.Chung KC, Rohrich RJ. Measuring surgical quality: is it attainable? Plast Reconstr Surg. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181958ee2. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]