Abstract

The switch point theorem (SPT) is the quantitative statement of the hypothesis that stochastic effects on survival, mate encounter, and latency affect individuals' time available for mating, the mean and variance in fitness, and thus, originally favored the evolution of individuals able to make adaptively flexible reproductive decisions. The SPT says that demographic stochasticity acting through variation in (i) individual survival probability, s; (ii) individual encounter probability, e; (iii) latency, l; (iv) the number of potential mates in the population, n; and (v) the distribution of fitness conferred, the w distribution, together affect average lifetime fitness, and induce adaptive switches in individual reproductive decisions. The switch point is the rank of potential mates at which focal individuals switch from accepting to rejecting potential mates, a decision rule that the SPT proves maximizes the average lifetime fitness of a focal individual under given values of ecological constraints on time. The SPT makes many predictions, including that the shape of the distribution of fitness conferred affects individual switch points. All else equal, higher probabilities of individual survival and encounter decrease the fraction of acceptable potential mates, such that focal individuals achieve higher average lifetime fitness by rejecting more potential mates. The primary prediction of the SPT is that each decision a focal individual makes is determined jointly by e, s, l, n, and the w distribution.

Keywords: demographic stochasticity, encounter probability, mate choice, sexual selection, survival probability

When Darwin's critics said that natural selection (1) could not explain the evolution of traits such as the outrageous tails of peacocks that reduce their bearers' survival probabilities, he countered with sexual selection (2). He argued that costly traits would evolve if they also increased males' abilities to attract females or to win behavioral contests over access to females. In “Principles of Sexual Selection,” the first chapter of Part II of The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (2), Darwin defined sexual selection as that type of selection that “ … depends on the advantage which certain individuals have over other individuals of the same sex and species, in exclusive relation to reproduction” (ref. 2, p. 256). Darwin distinguished sexual selection from natural selection as selection that arises from some individuals having a reproductive advantage over other same-sex, conspecific individuals, not from different “habits of life,” but from reproductive competition with rivals. Darwin's discussion focused overwhelmingly on traits in males that could be explained by 2 mechanisms of sexual selection - male-male competitive interactions and female choice—each of which could result in variation among males in fitness and thereby favor traits that helped males win fights and attract females (see ref. 3). Most modern discussions of typical sex roles begin with Darwin's 1871 volume, and statements about choosy females and profligate, competitive males. However, Darwin probably suspected that male choice was common; he argued in Part I of the 1871 book that men's choice of mates was seemingly more common than women's at least in “civilized societies.” He even argued that the beauty of women was due to male choice. In Part II he also described cases of male domestic and companion animals refusing to copulate with some females. He was aware too of gaudy, pugnacious, and competitive females in some bird species. Controversy over whether females had the esthetic capability for discrimination dogged Darwin and his followers into the 20th century.

After most people finally agreed that females had the sensibilities to choose, focus narrowed so that modern students of sexual selection simply assumed that males were competitive and indiscriminate and females “coy,” passive, and discriminating. For example, when Bateman (4) studied sex differences in fitness variances in Drosophila melanogaster, he attributed the larger variances of males to their “undiscriminating eagerness” and the “discriminating passivity” of the females (p. 367), even though he did not watch behavior (5). Bateman's study also led many to infer that female multiple mating was unlikely to be very common as it was unlikely to enhance female fitness.

Resistance to such “narrow-sense sexual selection” was afoot in Darwin's century (see citations in 6), and accelerated with the flush of empirical papers that followed Parker et al. (7) and Trivers (8). Parker argued that the sexes are what they are because of the size of the gametes they carry: females having large, relatively immobile, resource-accruing gametes and males having smaller, mobile gametes that competed for access to the larger ones. Trivers argued, echoing Williams (9), that females were usually the choosy sex because in most species females bore the greater cost of reproduction. Challenges to the generalizations of parental investment theory included Hrdy's (10) book about the near ubiquity of competitiveness of primate females and their anything but “coy” and “passive” sexual behavior; discovery that females fight females to defend “genetic maternity” in birds (11, 12), documentation of multiple mating by wild living female Drosophila pseudoobscura (13), Sialia sialis and other bird species (14, 15); and the first study of male mate choice in beetles with typical female-biased parental investment (16). Importantly, Sutherland (17–19) showed theoretically that the sex differences in fitness variances could arise in the absence of mate choice and intramale competition and could be due entirely to chance. Building on Sutherland's insights, Hubbell and Johnson (20) showed that the variation in lifetime mating success results from chance and selection, so that measures of selection should rely only on the residual variance that cannot be ascribed to known and quantifiable nongenetic life history variation. Hrdy and Williams (21) and Hrdy (22) offered an explanation for why, in the face of so much evidence, so many biologists seem invested in the “myth of the coy female.” In response to the failures of the simpler versions of parental investment theory, new theory to explain reproductive decisions appeared (20, 23, 24) predicting that variation in encounters, latencies, survival, and their more complex proxies (relative reproductive rate, the operational sex ratio, and density) favored shifts in mean behavior of the sexes, and as a result more nuanced reports of ecologically induced variation in sex-typical behavior appeared (e.g., refs. 25–39). Currently, few investigators think that sex role behavior is entirely fixed for either sex, particularly in females in species with female biased parental investment in which many observations of changes in mating behavior exist (25, 35, 40). Nevertheless, we know little about how male mate choice behavior varies under ecological constraints, because few investigators study male mate choice in species with female-biased parental investment. The possibility of sex role flexibility has seldom been simultaneously tested in both sexes (41).

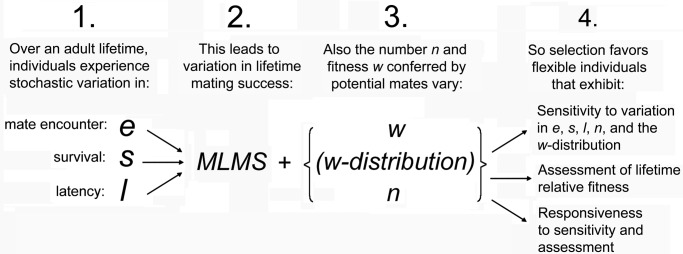

Most modern theories of sex roles begin with Trivers's (8), and Parker's et al. (7) ideas about sex differences to predict further sex differences. The derivative theories assume that the origin theories are an accurate reflection of past selection, which is an intuitive place to begin in refinement of theory—until one seriously considers the explicit challenges to the embedded assumptions about sex differences in fitness variances. Consider what Hubbell and Johnson (20) proved theoretically: that demographic stochasticity gives rise to chance variances in lifetime reproductive success. They proved that nonheritable environmental variation in an individual's lifetime number of mates could have favored the evolution of mate assessment in the first place. They showed that variances in number of mates similar or identical to those usually attributed to sexual selection could arise without mate choice and other sources of intrasexual competition. In other words, the arrow of causation linking classic mechanisms of sexual selection to fitness variances can go in either direction (42). This means that fitness variances can arise from demographic stochasticity, acting through chance effects on individual encounter probabilities with potential mates, individual survival probabilities, and latencies, which are variables that can then induce individual behavior (Fig. 1). This conclusion is turned around from the usual conclusion that mate choice and intrasexual competition cause fitness variances. This observation was profound, just as Sutherland's (17) earlier one was, because it showed that the usual linkage between mechanisms of sexual selection and means and variances in number of mates is best interpreted as correlation rather than causation until one partitions the deterministic and stochastic components of means and variances in number of mates.

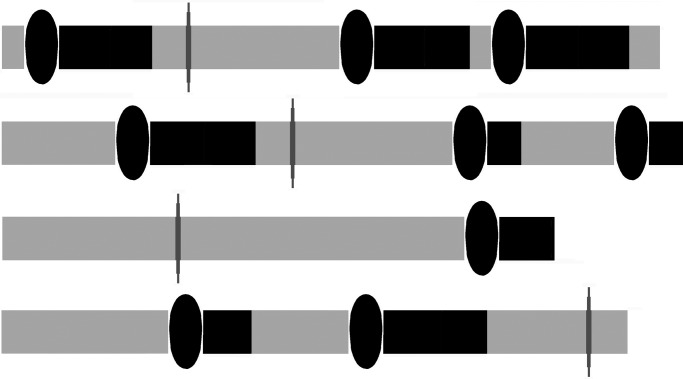

Fig. 1.

Scheme showing a scenario of the evolution of switches in reproductive decisions. Modified from ref. 42.

Most recent sex roles research has focused on female mate choice for fancy male traits, much of which was inspired by Hamilton and Zuk's (43) hypothesis that fancy male traits indicate good genes for offspring viability, a compelling hypothesis given Red Queen dynamics between hosts and pathogens. Later quantitative genetics theory suggested that indirect fitness effects are less likely than direct fitness effects to favor the evolution of such traits (44, 45). Additionally, until relatively recently, few data existed in support of the good genes hypothesis of mate choice. However, female and male choice studies in flies (46), cockroaches (47, 48), ducks (49, 50), and mice (39, 51, 52) have demonstrated that offspring viability was significantly higher when choosers were mated with discriminatees they preferred, as was productivity (the number of offspring surviving to reproductive age). In contrast, fecundity (the numbers of eggs laid or offspring born) was almost always lower and sometimes significantly lower when choosers were experimentally paired with partners they preferred compared with partners they did not prefer (53). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis of reproductive compensation (54) and inconsistent with theories predicting that mate choice favors enhanced fecundity.

Why were these studies (39, 46–51, 53) successful in showing the predicted associations between mate choice and offspring viability, when others were not? There are at least 3 reasons. First, the studies had controls that eliminated the effects of intrasexual behavioral contests and intersexual coercion that often confound mate choice studies (55). Second, these studies were not designed to understand the evolution of traits mediating preferences, but to test the effects of mate choice independent of their effect on the evolution of discriminatee traits. The investigators picked choosers and discriminatees at random with respect to their phenotypes, so these studies are silent about the traits in the discriminatees that mediated choosers' preferences. Questions about the evolution of fancy traits are really 2 separate questions: one about the fitness payouts of preferences, and the other about the evolution of the traits that mediate the preferences. Multiple traits may mediate preferences (56). However, few have evaluated the hypothesis that fancy traits may exploit preexisting sensory biases that could manipulate choosers in ways that could decrease rather than increase their fitness. Third, the investigators (53) were motivated to study the effects of constraints on the free expression of mate preferences, so their methodologies were designed to get unambiguous pretouching behavioral indicators that choosers preferred one discriminatee more than the other. Once the investigators knew whom the choosers liked and did not like, they randomly assigned the choosers to breed with one of the discriminatees. In that way, they captured the effects of constraints on the fitness payouts for choosers in unconstrained and constrained partnerships.

Why are these studies (39, 46–52, 53) of interest in an article on sex roles? (i) They provide powerful empirical counterpoint to theory that argues that indirect fitness effects are unlikely to accrue from mate preferences. (ii) They demonstrate trade-offs in components of fitness for choosers breeding under constraints, thus suggesting that to understand selection from mate choice, investigators may profit from knowing about as many components of fitness as possible, including fecundity, productivity, and offspring viability, when individuals breed under constraints. (iii) They show that individuals—both males and females—can and do make pretouching assessments of likely fitness payouts before mating. They made clear that males, not just females, are able to modify their behavior and physiology when breeding under constraints (53), observations inconsistent with typical ideas about sex role variation in species with female-biased parental investment.

What is needed now is a theory that will allow investigators to parse differential effects on fitness and behavior, and the direction of their effects on each other (behavior to fitness/fitness to behavior) on both females and males. Such a theory will allow investigators to attribute reproductive decisions and behavior to 3 causal factors (i) chance variation in ecological contingencies that may induce flexible and adaptive individual reproductive decisions; (ii) competitive forces including natural and sexual selection; and (iii) fixed sex differences. The model we present facilitates these goals.

To describe the model, which we call the switch point theorem (SPT), we (i) discuss individual reproductive time budgets, which encapsulate some of the most important ecological constraints on reproduction. (ii) We introduce the concept of the fitness conferred by alternative potential mates. (iii) We verbally describe the steps in model construction (the mathematical description is in online SI). (iv) We show some of the results of the model. In the discussion, we (v) list what the SPT does and does not do, and (vi) describe several possible empirical tests and applications of the SPT.

Constraints on Individual Reproductive Time Budgets.

For all mortal individuals, their time is finite. Time available for mating affects means and variances in number of mates (Fig. 1) (42), and chance effects on life-history that affect time available for mating can have strong effects on fitness means and variances (17, 20). The simplest set of parameters to affect lifetime variance in numbers of mates is based on stochastic effects on an individual's survival and the individual's encounters with potential mates, and, if the individual is a nonvirgin (i.e., a remating individual), its latency from one copulation to receptivity for the next (17, 20, 42). Indeed, in order for a receptive individual to mate, it must encounter a potentially mating opposite sex individual; thus an individual's encounter probability (e) with potential mates affects how much time the focal individual spends searching for mates. Likewise, for already-mated individuals in iteroparous species, the time they spend “handling” the reproductive consequences of mating, during which they are in latency (l) and unavailable for further mating, affects the time remaining for future matings and the opportunity cost of the past mating (17–19, 42). Importantly, individuals vary in reproductive life span, a function of their survival probability (s). All else equal, when search time and latencies are short, and life span is long, individuals have more time for reproduction than when search time and latencies are long, and life span is short. Individuals with short search times and long lives have more opportunities to mate than individuals whose search time is long and whose probability of future life is short. Intuitively (Fig. 2), it is easy to see that when opportunities vary, the costs and benefits of accepting or rejecting potential mates also vary. This means that for individuals with many opportunities, the costs of rejecting more potential mates are smaller, whereas, when focal individuals have fewer opportunities, the costs of rejecting potential mates are greater. However, relative opportunities predict only means and variances in number of mates; to predict adaptive, flexible reproductive decisions of an individual, one must also know the fitness that would be conferred if a focal individual were to mate with any given alternative potential mate.

Fig. 2.

Four stick models of idealized reproductive careers of 4 individuals. On each stick, the gray bars represent the stage, search. The ovals attached to black bars represent the time used when an individual encounters and accepts for mating a potential mate, and enters a latency, a period during which the individual is unreceptive to further mating. The gray vertical ovals attached to gray bars represent encountering and rejecting a potential mate, after which the individual reenters search. Some sticks are longer than others indicating that some individuals die before others, when they enter the absorbing state, death.

Fitness Distributions.

Just as most models of mate preferences do (57), the SPT assumes that individuals assess the fitness that would be conferred (w) by potential mates before making reproductive decisions. We further assume that individuals obtain information during their development of the distribution of fitness that would be conferred (the w distribution) by potential mates in their population. To conceptualize the meaning of w distributions, imagine an experiment with no carry-over effects in which every female in a population is mated with every male and every male with every female. Fill in every cell of a matrix with the fitness that would result from each pairwise mating. This matrix specifies what we mean by “fitness conferred by alternative potential mates.” We assume that focal individuals have information about the distribution, which is a key component of expected mean reproductive success. The fitness components one might consider empirically or theoretically include: fecundity (the number of eggs laid or offspring born), productivity (the number of their offspring that survive to reproductive age), or offspring viability (the proportion of eggs laid or offspring born that survive to reproductive age). On completion, one would have a matrix of values representing “fitness conferred by alternative potential mates, w.” One can imagine a variety of scenarios for how fitnesses are distributed in such a fitness matrix. For example, one might observe a situation in which w is as an absolute, meaning that all focal individuals rank a potential mate the same way, as predicted by many theories of sexual selection (57). Alternatively, w might often differ from one focal individual to another, as we think likely, and be an interaction effect and self-referential, meaning that each focal individual will not rank specific potential mates in the same way. Such self-referential mate preferences occur in mice and other organisms (58, 59). The entries in the fitness matrix have some statistical distribution, which we call the w distribution.

In the SPT, we assume the w distributions are beta distributions. The beta distribution is convenient because a beta random variate takes values from 0 to 1, as fitness does, and a beta distribution can assume a very large diversity of shapes depending on its 2 parameters, nu (ν) and omega (ω), from flat to strongly unimodal, left or right skewed, and even bimodal. We illustrate several possible fitness distributions in the analyses including beta (1, 1), which gives a uniform probability density from 0 to 1; beta (8, 3), which is skewed to high values; beta (3, 8), which is skewed to low values; and beta (5, 5), which has a strong central tendency. Note that although we use a beta probability density function in the SPT, there is no necessity for the w distribution to be beta for the SPT to be valid.

The Switch Point Theorem

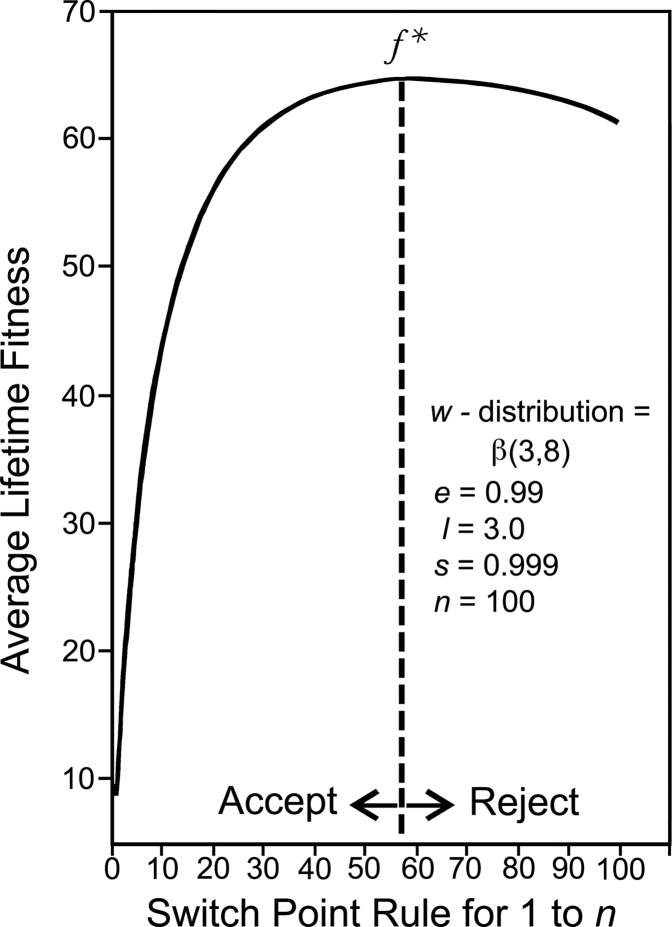

The SPT arises from a Markov chain state transition model. The SPT is a generalization of an earlier model (20, 42) in which focal individuals made mating decisions when potential mates occurred in only 2 qualities. In the current model, focal individuals make mating decisions when potential mates may occur in up to n qualities, where n is the number of potential mates in the population, so that there is a state for mating each potential mate. In Markov state transition models, individuals move from one state to another with some probability. The model is an absorbing Markov chain, so individuals continue to move through states until death (a terminal state individuals cannot leave). The solution to the model is a theorem that specifies the mean and the variance of the number of times the individual enters each state. The solution to the SPT (below) is ƒ*, the number of potential mates a focal individual finds acceptable that maximizes relative lifetime fitness. The SPT says that focal individuals should accept all potential mates whose rank (with 1 being the highest fitness rank) is less than or equal to the rank at which average lifetime fitness would be maximized (ƒ*); and reject all whose fitness rank is above ƒ*.

The SPT assumes that individuals encounter potential mates at random with respect to their rank, and shows that focal individuals who follow the mating decision rule to accept any potential mate i for which wi > wf*, and reject any potential mate j for which wj < wf*, will maximize their average lifetime reproductive fitness. Note that any given focal individual in this stochastic ensemble may not actually mate with all individuals having wi > wf*, in their lifetime. However, the rule that maximizes lifetime reproductive success is to find acceptable any individual encountered whose w is greater than wf*, the fitness of the potential mate at rank ƒ* (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

An example of a switch point graph.

Derivation of the SPT

The SPT proof is provided in the SI. Here, we describe the steps that allowed us to analytically solve for the number of potential mates that a focal individual should find acceptable to maximize the focal's average lifetime fitness.

In step 1, we constructed a series of absorbing Markov chain models for each decision rule associated with n, under specified ecological constraints affecting values of e, s, l, and the w distribution. If n = 3, for example, there are 3 decision rules and 3 matrices are required to deduce the rule that would maximize average lifetime fitness: (i) accept the potential mate ranked 1 and reject potential mates ranked 2 and 3; (ii) accept potential mates ranked 1 and 2 and reject the potential mate ranked 3; and (iii) accept all 3 potential mates. If n = 100, there are 100 decision rules and, without the SPT proof by induction (see SI), 100 matrices would have been required to deduce the rule that would maximize the focal individual's average lifetime fitness under specified values of e, s, l, n, and w distribution. The 100 rules take the following form: accept up to rank ƒ* (where ƒ * equals the highest acceptable rank), reject all from rank n − ƒ*. The probabilities associated with e, s, and l determine the mean number of times the focal will pass through each cell in each matrix. It is possible to solve this algebraically without specifying numerical values of e, s, l, or n.

In step 2, we computed for each decision rule the mean number of times that an individual passed through the mating state with each acceptable potential mate and multiplied this mean by the fitness, w, that would be conferred if the focal actually mated with the acceptable mate. The w for each potential mate comes from the specified beta distribution.

In step 3, we summed up these products from each decision rule for a focal with specified e, s, l, n, and w distribution to find ƒ*, the decision rule that would maximize average lifetime fitness, if the focal actually mated with each acceptable mate.

Because of social and ecological constraints (53), it is unlikely that focal individuals actually mate with all potential mates who are acceptable to them. Therefore, we characterize the rule as the “switch-point” at which focal individuals switch from accepting potential mates to rejecting them. That is, it is important to keep in mind that the SPT does not state that individuals actually mate up to ƒ*, only that they will accept any potential mate they encounter whose rank is 1 to ƒ*. Thus, the SPT is only a decision rule, not a statement of how many mates a focal individual will have. The SPT specifies whether to accept or reject a potential mate under chance effects from demographic and environmental stochasticity. The information embodied in the SPT is about future opportunities, and, if one actually mates with a potential mate, the opportunity costs associated with having mated with a particular potential mate. We hypothesize that individuals use this information to adjust their reproductive decisions as their ecological circumstances change. The “two body” problem that occurs when 2 individuals meet and one accepts but the other rejects cannot be studied in the current Markov chain model.

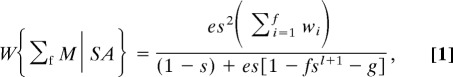

The analytical solution for a switch point set at ƒ, for which the derivation is the SI, is:

|

where g = n − ƒ.

The solution is the decision rule ƒ* that maximizes Eq. (1). Note that e, s, l, n, and the w distribution could be functions of 1 or more of the other parameters. There is nothing in the theorem that precludes such functional interactions between the parameters. We have presented the version without interaction for heuristic simplicity.

The SPT allows us to predict how an individual's switch point changes with changing ecological and life-history circumstances that affect e, s, l, n and w distribution, which we present next.

Results

Fitness Distributions Affect the Switch-Points of Focal Individuals.

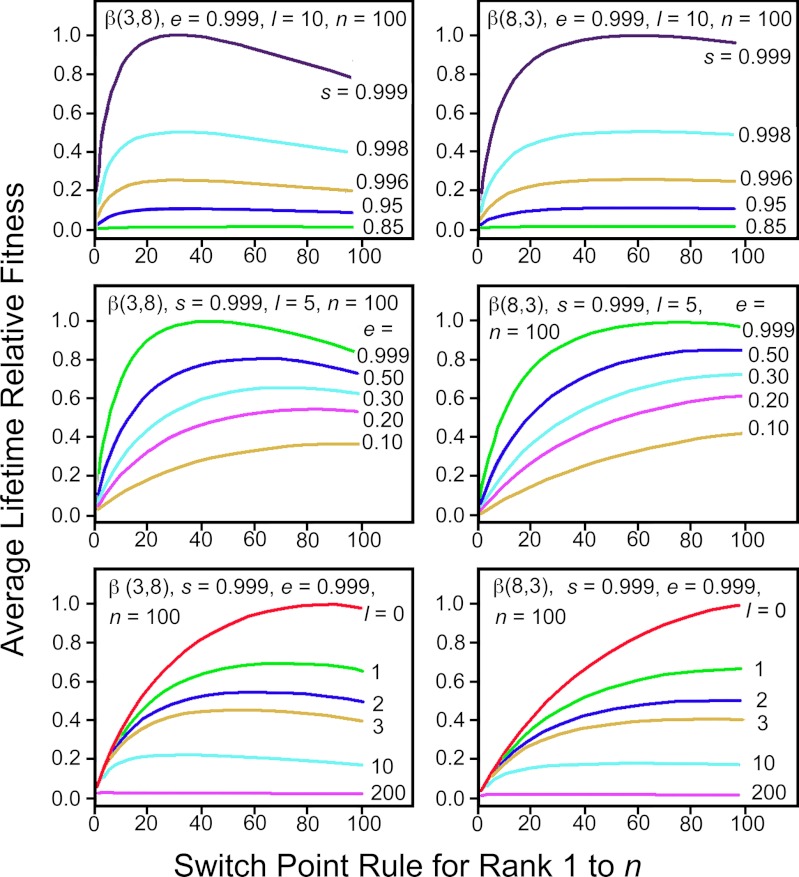

Fig. 4 shows how the switch point changes for a focal individual experiencing identical values of e, s, l, and n, when the w distribution varies. When the w distribution is right skewed, the fitness conferred at ƒ* is on average higher than when the w distribution is left skewed; and the fraction of acceptable mates is greater when w distributions are strongly right-skewed with many potential mates conferring high fitness.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the effects of different w distributions on the switch point when e, s, l, and n are held constant.

Variation in Number of Potential Mates.

In populations of different sizes, individuals with identical e will see different numbers of potential mates, with those in larger populations seeing more than those in small. The SPT predicts that individuals in larger populations, when holding e, s, l and the w distribution constant, reject a larger fraction of potential mates than those in smaller populations. This is because for a given e, s, or l a larger n allows focal individuals to sample a larger portion of the fitness distribution. Likewise, for a given e, s, and l, individuals in smaller populations will accept more mates, because they will sample a smaller portion of the fitness distribution.

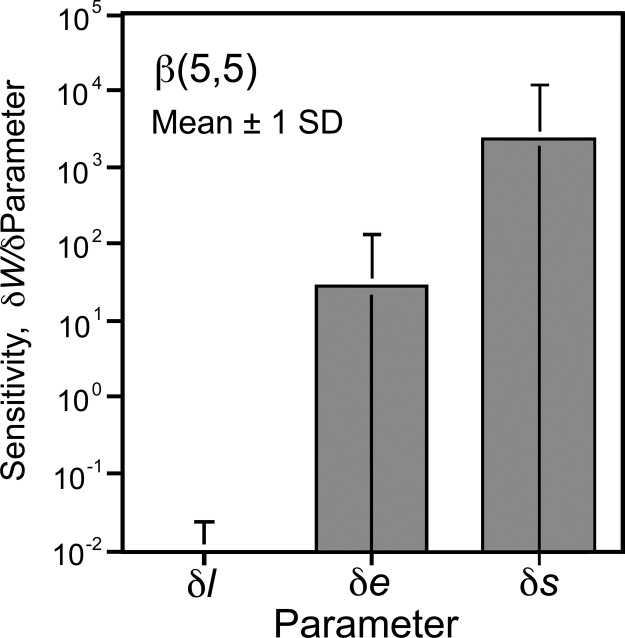

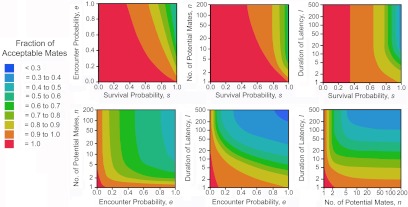

Variation in s Changes Individual Switch Points Most.

A sensitivity analysis of Eq. 1 indicates that changes in fitness with respect to changes in s, e, and l are such that dw/ds > dw/de > dw/dl (Fig. 5;further discussion in the SI). Of the 3 parameters, the greatest sensitivity is to s, and the least sensitivity is to l. As s → 1, the focal individual has a longer and longer mean life span, and the derivatives increase without bound. This is because total lifetime fitness at ƒ* is the sum of mean fitness conferred over all acceptable mates from rank 1 to rank ƒ*. Lifetime fitness at ƒ* is approximately 2 orders of magnitude less sensitive to changes in e than to changes in s. Lifetime fitness at ƒ* is least sensitive to l. The parameters also interact in their sensitivity effects on fitness. The interactions are manifest in the fact that the sensitivity of the fitness function at ƒ* to e, s, and l is a function of the specific values of the other parameters. For example, increasing e increases the sensitivity of fitness to s. Similarly, increasing s strongly increases the sensitivity of fitness to e.

Fig. 5.

The mean and standard deviation in the rate of change in log average lifetime fitness relative to changes in s, e, and l for a beta distribution with a strong central tendency.

Time Available for Mating Affects the Switch Points of Focal Individuals.

Increases in e, s, and n decrease the time to finding potential mates, thereby increasing reproductive opportunities for focal individuals, an effect that enhances the fitness benefit of rejecting more potential mates. The SPT shows that within a sex, individuals experiencing longer latencies must make up opportunity costs relative to individuals that experienced shorter latencies.

Changing More than One Parameter at a Time.

All else is seldom equal, and the SPT allows evaluation of the effects of variation in e, s, l, n, and w distribution on ƒ* while varying only 1 parameter, 2 parameters (Fig. 6),or all 5 parameters at a time.

Fig. 6.

Contour plots of the marginal means in fraction of acceptable mates when 2 parameters vary.

Discussion

What the SPT Does and Does Not Do.

The SPT makes no assumptions about underlying sex differences. We assume that individuals' time available for reproduction is finite, and we characterize variation in individual reproductive careers in terms of constraints on time available for mating. We simplify the parameters of previous theories and unify them in a general framework that provides a unique way to think about reproductive decisions (Fig. 1). We start simply with an individual and its time budget.

The SPT predicts the fraction of potential mates that a focal individual finds acceptable to mate. Each calculation of the switch point is about a single individual under specific values of ecological constraints on their time available for future reproduction. The SPT assumes that individuals assess the likely fitness that would be conferred by alternative potential mates before accepting or rejecting a potential mate. Furthermore, it ranks potential mates from highest fitness conferred (rank 1) to lowest fitness conferred (rank n, where n is the total number of alternative potential mates in the population). The SPT assumes that focal individuals encounter potential mates at random with respect to the rank the focal assigns them. The switch point is the rule (what lowest fitness rank to accept), which if obeyed, maximizes average lifetime fitness for a focal individual under specified time constraints. These constraints arise from social or ecological factors. The primary prediction of the SPT is that e, s, l, n, and the w distribution jointly determine each reproductive decision a focal individual makes.

The SPT is silent about how many times a focal individual actually mates, so that the SPT is accurately characterized as a model of the decision rule that a focal individual would use, if it encounters a particular potential mate. Because the absorbing Markov chain model is stochastic, some focal individuals may be unlucky during their entire lives and never encounter a potential mate. Because the SPT provides an analytical solution, one can calculate how many focal individuals, under different time constraints, may never encounter a potential mate. So, the SPT is a model of the decision rules—accept this one, reject that one, when potential mates come in up to n qualities, if the focal individual encounters that potential mate. We hypothesize that flexible individuals should use these rules under variation in opportunities for future matings and opportunity costs of realized matings.

The SPT is silent also about the proximate mechanisms mediating preferences. The SPT may be used to inform models of trait evolution under sexual selection (see below), but the SPT by itself is not a model about the evolution of traits in preferred individuals.

With the SPT, we are able to design studies to answer whether sex differences primarily are due to past selection on females for choosy behavior and on males for profligate, competitive behavior. With it, we are able to ask by what ways, and to what effects on fitness, do ecological and social constraints influence sex roles. With it, we are able to determine if contemporary assessments of future fitness costs and benefits induce individual reproductive decisions.

Are Both Sexes Flexible?

It is possible to empirically test the hypothesis that both sexes make flexible reproductive decisions, as the SPT predicts. Imagine an experiment in which individuals of both sexes develop in social environments in which they have controlled exposures to future potential mates. Imagine also that the population has been managed so that the w distribution for all individuals of either sex has the same shape (such as might occur in large out-bred populations without sex-biased dispersal) and that n is equal. In our thought experiment, investigators move all individuals into same-sex holding arenas just before they reach sexual maturity to guarantee that mating does not occur. Then, they carry out pretouching arena (such as the one pictured in ref. 46) tests, to measure the fraction of potential mates acceptable to focal individuals. Note that the experiments evaluating accept/reject responses must be tightly controlled so that subject's responses are not contaminated by intrasexual interactions among the discriminatees or sexual coercion (55). Then investigators manipulate one variable, say, e so that in similar time periods some focal individuals encounter fewer potential mates, and in other trials the same focal individuals encounter more potential mates. This experimental procedure would vary the focal individual's encounter rate with potential mates and, if carried out, would provide a strong within-subject test of the prediction that focal individuals reject more potential mates as e increases. Importantly, the SPT predicts that if e, s, l, n, and the w distribution are the same for all tested individuals, males and females will show no significant differences in their accept/reject behavior.

The SPT is an Alternative Hypothesis to Anisogamy Theory.

The SPT is not only a predictive hypothesis of when individuals should switch their reproductive decisions. It is also a strong alternative hypothesis that can be simultaneously tested along with classic ideas about the evolution of sex roles. Anisogamy theory is silent about ecological and temporal constraints on reproductive decision-making. It predicts that in species with gamete size asymmetries, such as D. pseudoobscura and D. melanogaster, that the sex with the larger gametes will reject more potential mates (i.e., “be choosier”) than individuals of the sex with the smaller gametes. In species, such as Drosophila hydei, with little or no gamete size asymmetries, anisogamy theory predicts that males and females should be similarly “choosy” and similarly “indiscriminate.” In contrast the SPT predicts that for both sexes in all 3 species, individuals will flexibly adjust their decisions to accept or reject particular mates as e, s, l, n and w distribution vary. These alternatives could be tested with a crucial experiment (60) in which a test of a single prediction—about accepting or rejecting potential mates—could simultaneously reject one hypothesis and provide support for the alternative.

The SPT is an Alternative Hypothesis to Parental Investment Theory.

For species in which parental investment is biased toward one sex, investigators could compete the predictions of the SPT with parental investment theory. Controlling for s, e, n, l, and w distribution for experimental subjects, the predicted behavior of individuals of different sexes would be the same under the SPT. Parental investment theory, by contrast, predicts that in a species with female-biased parental investment, females would reject more and males would accept more potential mates, whereas, in a species with male-biased parental investment, females would accept more and males reject more potential mates. Another valuable test would be of virgins of both sexes, for whom l = 0, in species with female-biased parental investment and in species with male-biased parental investment. As with anisogamy theory, these alternative predictions of the SPT and parental investment theory could be tested with a crucial experiment.

Almost Nothing is Known Empirically About w Distributions.

The w distribution has only been characterized for a few populations (unpublished data), and no one to our knowledge has tested the effects of w distributions on individual reproductive decisions. For laboratory populations of flies and other organisms with short generation times and no sex-biases in dispersal, it is relatively easy to estimate the shape of the w distribution, measuring fecundity, productivity, and offspring viability from a sample of random pairs breeding under enforced monogamy. An experiment that we plan to do will begin with flies cultured under inbreeding and outbreeding, which may produce w distributions with different shapes, and then to test the predictions (Fig. 5) for virgins (l = 0) when e, s, and n are held constant, using pretouching arenas.

Implications for Experimental Studies of Mate Preferences for Fancy Male Traits.

The SPT is not a hypothesis for the evolution of fancy male traits, nor does it predict the evolution of traits mediating preferences. Nevertheless, the SPT suggests that selection should favor traits that increase a focal individual's encounters with potential mates. Enhanced encounters increase reproductive opportunities, thereby reducing the opportunity costs of accepting potential mates who would confer low w. Traits, such as bizarre or easily seen plumage, loud calls, songs or pheromones that travel over large distances may attract more potential mates to the focal individual. In contrast to classic sexual selection ideas, however, the SPT predicts a different payout, not necessarily more mates, but in more reproductive opportunity. The SPT thus predicts that attractive focal individuals reject more potential mates than other, less attractive same-sex conspecifics, all else equal (i.e., if s, l, n and w distribution are equal for attractive and unattractive focals). This prediction has not been made by any hypothesis of classic sexual selection.

The SPT suggests that many previous failures to associate fitness rewards for female mate choice for fancy traits in males might be explained by experimentally uncontrolled variation in e, s, l, n or w distribution. The SPT predicts that a focal individual exposed only to a small number of potential mates would fail to show a preference. It is also possible that investigators have exposed females to males of nearly equivalent fitness. If this were the case, adaptively flexible females would more often accept potential mates, because the differences in w between potential mates may be very small, thus reducing the opportunity costs from any particular mating. Thus, the SPT may inform previous ambiguities in mate preference studies.

The Ecology of Sex Roles.

Thinking about time constraints on reproductive decisions suggests a new, powerful framework for sex differences research. If individuals of different sexes have different feeding niches and/or different exposure to pathogens or predators, there are likely to be associated differences in e, s, and l experienced by individuals of different sexes and, as the SPT predicts, differences in the typical reproductive decisions of individuals of different sexes. Or, if species in which one sex disperses, but the other does not, individuals of different sexes may see different w distributions and therefore express differences in the fraction of potential mates acceptable. Thus, it is possible that sex differences in typical reproductive decisions may have more to do with what Darwin called “habits of life,” rather than to fixed sex differences. Data on how different habits of life affect e, s, l, n, and w distribution of individuals are not yet systematically collected to our knowledge, and may prove interesting indeed, perhaps providing a path toward resolution of the some of the controversies that dogged Darwin and his followers up to the current day.

Acknowledgments.

We thank John Avise and Francisco Ayala for inviting P.A.G. to contribute to the Arthur M. Sackler Colloquia of “In the Light of Evolution III: Two Centuries of Darwin” and J. P. Drury, Brant Faircloth, Graham Pyke, Steve Shuster, and Elliott Sober for comments on a previous version of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant “Beyond Bateman,” which has allowed us and our collaborators, W. W. Anderson and Y.K. Kim, to study variances in number of mates and reproductive success in 3 species of flies with different gamete size asymmetries.

Footnotes

This paper results from the Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy of Sciences, “In the Light of Evolution III: Two Centuries of Darwin,” held January 16–17, 2009, at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center of the National Academies of Sciences and Engineering in Irvine, CA. The complete program and audio files of most presentations are available on the NAS web site at www.nasonline.org/Sackler_Darwin.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0901130106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Darwin C. On the Origin of Species. London: J. Murray; 1859. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darwin C. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: J. Murray; 1871. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones AG, Ratterman NL. Mate choice and sexual selection: What have we learned since Darwin? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(Suppl):10001–10008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901129106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman AJ. Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity. 1948;2:349–368. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1948.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewsbury DA. The Darwin-Bateman paradigm in historical context. J Integra Comp Biol. 2005;45:831–837. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gowaty PA. In: Modern Controversies in Evolutionary Biology In Science and Technology in Society: From Space Exploration to the Biology of Gender. Klienman DL, Handelsman J, editors. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 2007. pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker GA, Baker RR, Smith VGF. The origin and evolution of gamete dimorphism and the male-female phenomenon. J Theor Biol. 1972;36:529–553. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(72)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivers RL. In: Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man. Campbell B, editor. Chicago: Aldine; 1972. pp. 136–179. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams GC. Adaptation and Natural Selection. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hrdy SB. The Woman That Never Evolved. Cambridge: Harvard Univ Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gowaty PA. The aggression of breeding eastern bluebirds Sialia sialis toward each other and intra- and inter-specific intruders. Anim Behav. 1981;29:1013–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gowaty PA, Wagner SJ. Breeding season aggression of female and male eastern bluebirds (Sialia sialis) to models of potential conspecific and interspecific eggdumpers. Ethology. 1987;78:238–250. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson WW. Frequent multiple insemination in a natural population of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Am Nat. 1974;108:709–711. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowaty PA. In: Avian Monogamy, Ornithological Monographs. Gowaty PA, Mock DW, editors. Vol 37. McLean, VA: American Ornithologists' Union; 1985. pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowaty PA, Karlin AA. Multiple parentage in single broods of apparently monogamous eastern bluebirds (Sialia sialis) Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1984;15:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson LK, Hubbell SP. Male Choice: Experimental demonstration in a Brentid weevil. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1984;15:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutherland WJ. Chance can produce a sex difference in variance in mating success and account for Bateman's data. Anim Behav. 1985;33:1349–1352. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutherland WJ. In: Oxfords Surveys in Evolutionary Biology. Dawkins R, Ridley M, editors. Vol 2. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 1985. pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutherland WJ. In: Sexual Selection: Testing the Alternatives. Bradbury JW, Andersson MB, editors. New York: John Wiley & Sons Limited; 1987. pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubbell SP, Johnson LK. Environmental variance in lifetime mating success, mate choice, and sexual selection. Am Nat. 1987;130:91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hrdy S, Williams GC. Behavioral biology and the double standard. In: Wasser S, editor. Social Behavior of Female Vertebrates. New York: Academic; 1983. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hrdy SB. Empathy, polyandry and the myth of the “coy” female. In: Bleier R, editor. Feminist Approaches to Science. New York: Pergamon; 1986. pp. 119–146. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowley PH, et al. Mate density, predation risk, and the seasonal sequence of mate choices: A dynamic game. Am Nat. 1991;137:567–596. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clutton-Brock TH, Parker GA. Potential reproductive rates and the operation of sexual selection. Q Rev Biol. 1992;67:437–456. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnhagen C. Predation risk as a cost of reproduction. Trends Ecol Evol. 1991;6:183–186. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(91)90210-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forsgren E. Predation risk affects mate choice in a Gobiid fish. Am Nat. 1992;140:1041–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shelly TE, Bailey WJ. Experimental manipulation of mate choice by male katydids—the effect of female encounter rate. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1992;30(3–4):277, 282. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berglund A, Rosenqvist G. Selective males and ardent females in pipefishes. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1993;32:331–336. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedrick AV, Dill LM. Mate choice by female crickets is influenced by predation risk. Anim Behav. 1993;46:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berglund A. The operational sex-ratio influences choosiness in a pipefish. Behav Ecol. 1994;5:254–258. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulin R. Mate choice decisions by parasitized female upland bullies, Gobiomorphus breviceps. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1994;256:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berglund A. Many mates make male pipefish choosy. Behaviour. 1995;132:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simmons LW. Relative parental expenditure, potential reproductive rates, and the control of sexual selection in katydids. Am Nat. 1995;145:797–808. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dill LM, Hedrick AV, Fraser A. Male mating strategies under predation risk: do females call the shots? Behav Ecol. 1999;10:452–461. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grand TC, Dill LM. Predation risk, unequal competitors and the ideal free distribution. Evol Ecol Res. 1999;1:389–409. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itzkowitz M, Haley M. Are males with more attractive resources more selective in their mate preferences? A test in a polygynous species. Behav Ecol. 1999;10:366–371. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gowaty PA, Steinichen R, Anderson WW. Mutual interest between the sexes and reproductive success in Drosphila pseudoobscura. Evolution. 2002;56:2537–2540. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiggins FM. Widespread “hilltopping” in Acraea butterflies and the origin of sex-role-reversed swarming in Acraea encedon and A-encedana. African J Ecol. 2002;40:228–231. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drickamer LC, Gowaty PA, Wagner DM. Free mutual mate preferences in house mice affect reproductive success and offspring performance. Anim Behav. 2003;65:105–114. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gong A. The effects of predator exposure on the female choice of guppies (Poecilla reticulata) from a high-predation population. Behaviour. 1997;134:373–389. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gowaty PA, Steinechen R, Anderson WW. Indiscriminate females and choosy males: Within- and between-species variation in Drosophila. Evolution. 2003;57:2037–2045. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gowaty PA, Hubbell SP. Chance, time allocation, and the evolution of adaptively flexible sex role behavior. J Integrat Comp Biol. 2005;45:931–944. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.5.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton WD, Zuk M. Heritable true fitness and bright birds: A role for parasites? Science. 1982;18:384–387. doi: 10.1126/science.7123238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirkpatrick M. Evolution of female choice and male parental investment in polygynous species: The demise of the “sexy son.”. Am Nat. 1985;125:788–810. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf JB, Wade MJ. On the assignment of fitness to parents and offspring: Whose fitness is it and when does it matter? Evol Biol. 2001;14:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson WW, Kim Y-K, Gowaty PA. Experimental constraints on female and male mate preferences in Drosophila pseudoobscura decrease offspring viability and reproductive success of breeding pairs. 2007;104:4484–4488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611152104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore AJ, Gowaty PA, Moore PJ. Females avoid manipulative males and live longer. J Evol Biol. 2003;16:523–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore AJ, Gowaty PA, Wallin WJ, Moore PJ. Sexual conflict and the evolution of female mate choice and male social dominance. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2001:517–523. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bluhm CK, Gowaty PA. Reproductive compensation for offspring viability deficits by female mallards, Anas platyrhynchos. Anim Behav. 2004;68:985–992. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bluhm CK, Gowaty PA. Social constraints on female mate preferences in mallards Anas platyrhynchos decrease offspring viability and mother's productivity. Anim Behav. 2004;68:977–983. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drickamer LC, Gowaty PA, Holmes CM. Free female mate choice in house mice affects reproductive success and offspring viability and performance. Anim Behav. 2000;59:371–378. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gowaty PA, Drickamer LC, Holmes S-S. Male house mice produce fewer offspring with lower viability and poorer performance when mated with females they do not prefer. Anim Behav. 2003;65:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gowaty PA, et al. The hypothesis of reproductive compensation and its assumptions about mate preferences and offspring viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15023–15027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706622104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gowaty PA. Reproductive compensation. J Evol Biol. 2008;21:1189–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kingett PD, Lambert DM, Telford SR. Does mate choice occur in Drosophila melanogaster? Nature. 1981;293:492. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Candolin U. The use of multiple cues in mate choice. Biol Rev. 2003;78:575–595. doi: 10.1017/s1464793103006158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andersson M. Sexual Selection. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryan KK, Altmann J. Selection for male choice based primarily on mate compatibility in the oldfield mouse, Peromyscus polionotus rhoadsi. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2001;50:436–440. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryan KK, Lacy RC. Monogamous male mice bias behaviour towards females according to very small differences in kinship. Anim Behav. 2003;65:379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Platt JR. Strong inference. Science. 1964;146:347–353. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3642.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]