Abstract

Human harvest of phenotypically desirable animals from wild populations imposes selection that can reduce the frequencies of those desirable phenotypes. Hunting and fishing contrast with agricultural and aquacultural practices in which the most desirable animals are typically bred with the specific goal of increasing the frequency of desirable phenotypes. We consider the potential effects of harvest on the genetics and sustainability of wild populations. We also consider how harvesting could affect the mating system and thereby modify sexual selection in a way that might affect recruitment. Determining whether phenotypic changes in harvested populations are due to evolution, rather than phenotypic plasticity or environmental variation, has been problematic. Nevertheless, it is likely that some undesirable changes observed over time in exploited populations (e.g., reduced body size, earlier sexual maturity, reduced antler size, etc.) are due to selection against desirable phenotypes—a process we call “unnatural” selection. Evolution brought about by human harvest might greatly increase the time required for over-harvested populations to recover once harvest is curtailed because harvesting often creates strong selection differentials, whereas curtailing harvest will often result in less intense selection in the opposing direction. We strongly encourage those responsible for managing harvested wild populations to take into account possible selective effects of harvest management and to implement monitoring programs to detect exploitation-induced selection before it seriously impacts viability.

Keywords: conservation, genetic change, human exploitation

Humans have exploited wild populations of animals for food, clothing, and tools since the origin of hominids. Human harvest of wild populations is almost always nonrandom. That is, individuals of certain size, morphology, or behavior are more likely than others to be removed from the population by harvesting. Such selective removal will bring about genetic change in harvested populations if the selected phenotype has at least a partial genetic basis (Table 1). For example, the frequency of elephants (Loxodonta africana) without tusks increased from 10% to 38% in South Luangwa National Park, Zambia, apparently brought about of poaching of elephants for their ivory (1). Similarly, trophy hunting for bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in Alberta, Canada caused a decrease in horn size because rams with larger horns had a greater probability of being removed from the population by hunting (2). It has also been suggested that the greater difficulty of catching introduced brown trout (Salmo trutta) than native North American species of trout is the result of angling for brown trout in Europe for hundreds of years before their introduction to North America (3). Moreover, harvest need not be selective to cause genetic change; uniformly increasing mortality independent of phenotype will select for earlier maturation (4).

Table 1.

Traits likely to be affected by unnatural selection in harvested populations

| Trait | Selective action | Response(s) | Remedy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age and size at sexual maturation | Increased mortality | Sexual maturation at earlier age and size, reduced fertility | Reduce harvest mortality or modify selectivity of harvest |

| Body size or morphology, sexual dimorphism | Selective harvest of larger or more distinctive individuals | Reduced growth rate, attenuated phenotypes | Reduce selective harvest of large or distinctive individuals |

| Sexually selected weapons (horns, tusks, antlers, etc.) | Trophy hunting | Reduced weapon size or body size | Implement hunting regulations that restrict harvest based on size or morphology of weapons under sexual selection |

| Timing of reproduction | Selective harvest of seasonally early or late reproducers | Altered distribution of reproduction (truncated or altered seasonality) | Harvest throughout reproductive season |

| Behavior | Harvest of more active, aggressive or bolder (more vulnerable to predation) individuals | Reduced boldness in foraging or courtship behavior, potentially reduced productivity | Implement harvest methods less likely to impose selection on activity or aggressive behavior |

| Dispersal/migration | Harvest of individuals with more predictable migration patterns | Altered migration routes | Interrupt harvest with key time and area closures tied to primary migration routes |

In agriculture, the practice for thousands of years has been to use the most productive animals (and plants) as breeding stock, with the goal of increasing the frequency of desirable phenotypes. Aquaculture has adopted similar objectives over its shorter history (5). In contrast, the opposite has been true in the exploitation of wild animal populations. The most desirable individuals have been harvested, leaving behind the less desirable to reproduce and contribute genes to future generations. Therefore, harvest of wild populations has tended to increase the frequency of less desirable phenotypes in wild populations.

There has been surprisingly little consideration of human-induced selection in the wild until recently (reviewed in ref. 6). Even more surprising perhaps is the absence of any detailed consideration of this effect by Darwin because he had such a passion for hunting as a young man. In several places, Darwin commented on the lack of wildness of birds on islands where they have not been hunted by humans (page 400, ref. 7 and page 231, ref. 8). In his lengthy consideration of “Selection by Man” (9), Darwin considered in great detail the 3 types of selection that have produced domesticated plants and animals: methodological, unconscious, and natural, but he did not apply these principles to wild animals and plants. Nevertheless, he was aware that removing desirable animals by hunting could decrease the frequency of more desirable phenotypes, as indicated by the quote below. However, Darwin did not discuss the evolutionary consequences of hunting and how they might influence natural or sexual selection.

“Natural” is sometimes defined as not being affected by human influence (10). We adopt the term “unnatural” to describe unintended selection through exploitation because it is imposed by human activity in contrast to natural selection. Unnatural selection generally acts at cross purposes to the long-term goal of sustainable harvest of wild populations and can reduce the frequency of phenotypes valued by humans.

Harvest can affect sexual selection because it tends to remove individuals with particular characteristics, such as large size or elaborate weapons from those of the breeding pool. Sexual selection can act in concert with natural selection on some of these same traits (as well as others), with complex results (e.g., ref. 11). Sexual and natural selection can act simultaneously to change the frequency of particular phenotypes, depending on the intensity of natural prebreeding mortality (e.g., through predation or disease), breeding density, and the characteristics of breeding adults (e.g., frequency-dependent selection). Because different environmental conditions and population features favor different phenotypes, natural and sexual selection can interact in complex ways in different places and at different times to affect the characteristics of successful breeders.

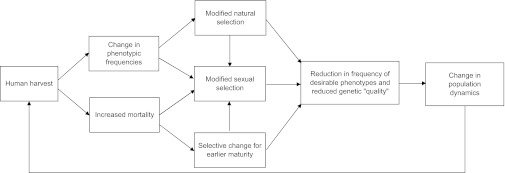

The objective of this article is to summarize the consequences of unnatural selection and sexual selection in wild populations of animals (Fig. 1), outline why these consequences threaten future yield and population viability, and suggest some measures to address this problem.

Fig. 1.

Human harvest can have a variety of direct and indirect genetic effects on populations, and it has the potential to affect the future yield and viability of exploited populations.

History of Unnatural Selection

So that the Incas followed exactly the reverse system of that which our Scottish sportsman are accused of following, namely, of steadily killing the finest stags, thus causing the whole race to degenerate.

Darwin (ref. 9, page 192)

Recognition that exploitation of wild animals can produce evolutionary change is not new. It was recognized for fishing by the late 19th century and for hunting by the early 20th century. However, few studies have been able to clearly document evolutionary response to exploitative selection, and the possibility that exploitation-induced evolutionary change can oppose adaptive responses to natural and sexual selection has not been widely appreciated. Nevertheless, Coltman (12) argued that rapid contemporary evolution has now been shown to occur in response to invasive species, habitat degradation, and climate change, and exploitation, and he went on to say that exploitation-induced evolution may well have the most dramatic impact of any of these anthropogenic sources of selection to date. Mace and Reynolds (13) asked why sustainable exploitation is so difficult, and pointed to limits of biological knowledge and limits of control as the 2 primary factors that cause exploitation to be such a challenge for conservation.

Fisheries and wildlife managers have yet to adopt management strategies that guard against rapid evolutionary response to exploitation. Managers have focused on demographic parameters that affect population abundance and growth rate because their primary goal is sustainable yield in the short-term. However, recognition is growing that evolution under exploitation can reduce population growth and viability and ultimately might reduce yield (14, 15). A recent analysis has concluded that phenotypic changes in response to human harvest are much more rapid on average than changes in natural systems (16). Sustainable harvests will eventually require that fisheries and wildlife managers incorporate genetic principles into the management of wild populations. Allendorf et al. (6) recommended that managers begin by acknowledging that exploitation produces some genetic change and implementing routine monitoring to detect harmful evolutionary change before it threatens productivity.

Fish can be killed through fishing either as immature or mature individuals, depending on the characteristics of the individual fishery; the point in the life history at which fishing mortality is exacted has important ramifications for fisheries-induced evolution (17). The relatively high fecundities and high natural mortality rates, especially early in life, for many fishes, mean that although fishing mortality can be high in some years, it is not often as high as natural mortality. By contrast, hunting mortality is often substantially higher than natural mortality for adult game animals (18), a contrast that has important implications for evaluating the differences between fishing and hunting.

Fishing

Evidence is mounting that fish populations will not necessarily recover even if overfishing stops. Fishing may be such a powerful evolutionary force that we are running up a Darwinian debt for future generations.

Loder (19)

Fish size is of primary interest to fishermen; larger fish are often of higher value. Larger, older fish can also contribute disproportionately to productivity through greater weight-specific fertility and larval quality (e.g., refs. 20 and 21). There are widespread accounts supporting claims that large fish were caught more frequently in commercial fisheries in the early years of those industries. For example, a gigantic Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) weighing nearly 100 kg was caught off Massachusetts in May 1895, and large cod (> 30 kg) were frequently taken from New England waters before 1900 (22).

Concern that removal of the larger individuals from breeding populations could affect populations emerged shortly after commercial fisheries for salmon expanded in the western United States in the late 19th century. In California, Rutter (23) speculated that salmon fisheries might enhance representation of smaller, younger fish among breeding males and that removal of larger adults could eventually reduce adult size and fishery yield. Smith (24) stated that capture of immature fish in ocean salmon fisheries could reduce future yield if maturation became earlier under such fishing mortality. However, others such as Miller (3), although acknowledging the potential of evolutionary response to selective fishing, apparently believed that the extensive plasticity of growth and maturation would mitigate against selection for rapid growth and early maturation of fish like salmon. Nevertheless, some scientists remained concerned about deleterious fisheries-induced evolution. Handford et al. (25) stated that management was “seriously deficient in [its failure] to take into account the possibility of adaptive genetic change in exploited stocks of fish.”

In the last few years, such concerns about capture fisheries for a variety of species have escalated (4, 26–28). Nevertheless, in large part because direct evidence for fisheries-induced evolution in specific cases remains elusive (17), fishery management almost nowhere yet incorporates evolutionary considerations: Fisheries are managed on the basis of demographic considerations alone—primarily adult abundance. Unfortunately, fisheries tend to impose selection that alters distributions of characteristics that affect fitness and population viability, principally through removal of larger and older fish that differ in growth, development, and reproductive characteristics. To the extent that size, age, and correlated traits in such fish are heritable (4, 29–30), fishing selection will tend to reduce means and alter variability for these traits over time.

This form of selection is thought to oppose natural and sexual selection on these traits, and the fisheries-induced evolution that is likely to result from such selection will favor trait phenotypes among breeders that differ substantially from those targeted in fisheries (31). That is, fisheries-induced evolution will tend to proceed along a trajectory that is counter to one that maintains trait combinations desirable to fishermen. Exploitative selection imposed by fishing tends to reduce the frequency of desirable phenotypes through directional selection for alternative phenotypes, unlike other human-induced forms of selection, such as domestication, which often produce maladapted phenotypes indirectly by favoring alternative optima through alteration of the natural selection regime (e.g., ref. 32).

Recreational fisheries can also bring about a genetic response to angling. However, there has been little work done in this area. Some authors have reported differences in angling vulnerability between domestic and wild strains of fish (33, 34). Biro and Stamps (35) argued that behaviors such as boldness and activity, which are often correlated with growth rate, are likely to affect productivity and could respond to selective mortality. Philipp et al. (36) reported differences in hook-and-line angling vulnerability between individual largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) in a wild population. The authors estimated a realized heritability of 0.15 through a 3-generation selection experiment.

Few studies have estimated the intensity of selection that fishing exerts. Although mortality of fish caught in many fisheries tends to increase with fish size, producing negative selection differentials (37), these estimates also appear to vary substantially from place to place and over time (17, 25, 38–42) and between the sexes (43). Kendall et al. (44) estimated standardized selection differentials for a 60-year dataset of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) and found that selection intensity often differed substantially between sexes of returning fish and among years, although selection was generally higher on larger fish (especially females). Hard et al. (17) concluded that estimates of selection intensity resulting from fishing were generally modest and typically less than the few estimates of natural and sexual selection differentials that have been reported for species like Pacific salmon (11, 45–47). Nevertheless, even fisheries that are not highly selective are expected to produce evolutionary change if fishing mortality is high enough (48).

Estimates of natural selection gradients in salmon, for example, can vary widely but are typically in the range of 0.5 standard deviations (SD) or less (e.g., ref. 47). Hamon and Foote (ref. 11; see also ref. 45) estimated standardized sexual selection differentials on morphology and run timing that ranged between −0.14 and +0.52 (linear) and between −0.29 and +0.11 (nonlinear), and sexual selection gradients on these traits that ranged between −0.16 and + 0.33 (linear) and between −0.33 and 0 (nonlinear). Total selection estimates that combined natural and sexual selection intensities tended to be smaller, in general, and sexual selection on morphology was often stronger than natural selection. Furthermore, several of the predicted consequences of selective fishing (such as earlier maturation and greater reproductive effort) are similar to those expected from ecological changes after a decrease in population density. For this reason, ecological and evolutionary responses are usually difficult to tease apart with temporal phenotypic trends alone.

Nevertheless, selection of this intensity is not inconsistent with estimates of natural selection in nature (49) and might be sufficiently strong to produce rapid evolutionary change in many cases. In their long-term study of Windermere pike (Esox lucius) in England, Edeline et al. (50) contrasted temporal patterns of natural and fishing selection on this species; it was the first study to relate these patterns to long-term trends in life-history characteristics of wild fish (12). They estimated a substantial, fishing-induced negative selection differential on the reaction norm describing variation in gonad weight/body length, a measure of reproductive investment, in age-3 females. The temporal dynamics of life history appear to reflect the combined influences of a half century of natural and fishing selection; growth rate and reproductive investment at younger ages tended to decline during periods of higher exploitation, a pattern that diminished when fishing rates eased.

Hunting

I suggest that minimizing the impact of sport hunting on the evolution of hunted species should be a major preoccupation of wildlife managers.

Marco Festa-Bianchet (18)

Like fishery managers, wildlife managers have typically placed a primary emphasis on the demographic consequences of hunting, with little direct consideration of potential evolutionary effects (51). European wildlife managers have paid more attention than their North American counterparts to the selective effects of hunting, and hunting in Europe has often targeted specific phenotypic characteristics of game; as a result, European hunting regulations are typically more specific than American regulations (18, 52).

Game and especially trophy hunting generally differ from fishing in several ways. For example, key aspects of the life histories of the 2 groups of animals often differ. Game hunting often focuses on animals with relatively low reproductive output, and relatively low natural mortality rates; many fishes have higher fecundities and higher natural mortality rates than game animals. We expect that hunting selection could have a considerable effect on the evolution of adult characteristics, particularly those in prime-aged adults under sexual selection because hunting mortality is often substantially higher than natural mortality for adult game animals (18, 53).

Virtually all hunting invokes selective elements of some kind. These elements are often associated with particular phenotypic characteristics such as body size, coat color, and weapons or ornaments such as horns and antlers. As is the case for fishing, hunting for many animals can produce the paradoxical situation of selecting against the traits that are preferred by hunters (18). Because variation in many of these traits has an appreciable genetic component (54–57), such selection is likely to produce detectable evolutionary responses that reduce the ability of breeders with desirable characteristics to contribute to reproduction (58). Harris et al. (52) argued that available information is sufficient to recommend hunting patterns that minimize deviations of sex- and age-specific mortality rates from natural mortality rates.

Harris et al. (52) and Allendorf et al. (6) identified 3 primary genetic consequences of hunting: alteration of population structure, loss of genetic variation, and evolution resulting from selection. These general consequences apply to all forms of human exploitation. An early study by Voipio (59) was one of the first to show that the genetic consequences of selective hunting were likely to vary with the phenotypic characteristics of the hunted animals. In a simple, discrete-locus simulation of harvest of antlered male red deer (Cervus elaphus), Thelen (60) demonstrated how the frequency of alleles influencing large antler size, and therefore the yield of trophy males, would decline under different harvest management strategies. With regard to the loss of genetic diversity that can result from hunting mortality, Harris et al. (52) and Allendorf et al. (6) focused on the relationship between harvest and decline in heterozygosity or allelic diversity and how they are reflected in reduced effective population size (Ne) and the ratio of Ne to census size (Nc). These metrics are important indicators of a population's evolutionary potential, and substantial reductions in them can indicate unsustainable practices.

Several key population characteristics can affect genetic variability and adaptive potential. In most ungulates, for example, breeding population size, generation length and adult longevity, and mating structure, including the breeding sex ratio and harem size, can have a large influence on the dynamics of genetic and phenotypic variation under exploitation (61–64). Exploitation tends to skew the breeding sex ratio (65) and reduce adult longevity, especially of males, and mean male reproductive success and variance in progeny number per family. However, sex ratio can also be sensitive to population density (66, 67). These factors have a direct influence on Ne. If the mean generation length differs for males and females, which is common for several of these species, exploitation can also contribute to a reduction in Ne. The consequences of reduced Ne for adaptive potential can be serious, but they depend critically on the characteristics of the life history (68).

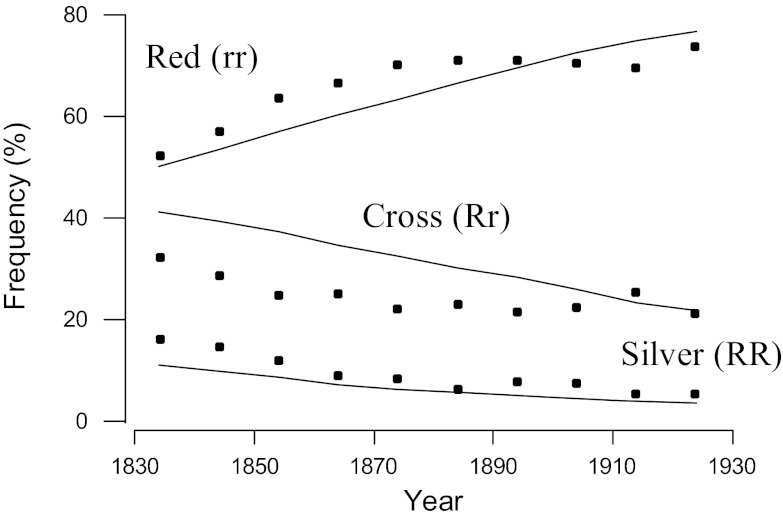

The reduction in the frequency of the silver morph in the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) between 1834 and 1933 in eastern Canada was perhaps the first documented change over time resulting from selective harvest (69). J. B. S. Haldane used these data to provide one of the first estimates of the strength of selection in a wild population using his then recently developed mathematical models of the effects of selection on a single locus (70). The fur of the homozygous silver morph (RR) was worth approximately 3 times as much as the fur of the cross (Rr) or red (rr) fox to the furrier, and, therefore, was more likely to be pursued by hunters. The fur of the heterozygous cross fox (Rr) was smoky red and was classified as red in the fur trade. The frequency of the desirable silver morph declined from ≈16% in 1830 to 5% in 1930 (Fig. 2). Haldane (70) concluded that this trend could be explained by a slightly greater harvest rate of the silver than the red and cross phenotypes. The lines in Fig. 2 show the expected change in phenotypic frequencies, assuming that the relative fitness of the silver phenotype was 3% less than both the red and cross phenotypes, and the generation interval was 2 years.

Fig. 2.

Reduction in frequency of the silver morph of the fox in eastern Canada resulting from the preferential harvest by hunters of the more valuable silver morph (69, 70). The points represent data presented by Elton (69). The lines represent the expected change in frequencies of the 3 phenotypes via selection at a single locus assuming that the silver fox morph has a 3% survival disadvantage per generation relative to the red and cross morphs. The initial frequency of the R allele was 0.3 and the mean generation interval was 2 years (70).

For roe deer, Hartl et al. (71) concluded that the intensity of harvest influenced the degree of selection against large body size, larger number of antler points and yearling males with small spikes; harvest intensity also affected the length of the antler main beam and produced changes in allele frequencies (see also 72). For mountain sheep, Coltman et al. (2) showed that harvest of trophy rams led to selection for lighter and smaller-horned rams. Different hunters invoke different methods in being selective, and Martínez et al. (73) argued that the urge for hunters to kill males with large antlers and to maximize opportunity to be selective by hunting early in the season were primary motivations. Mysterud et al. (74) found that hunter type (local vs. “foreign”) provided substantial variation in terms of temporal and spatial components of hunting activity, and that although the activities of the different hunter types influenced the relationship between age and antler mass, much of this influence arose from variation in the timing and location of hunting.

In their simulation of the evolution of exploited red deer, Hard et al. (75) found that selective hunting could reduce Ne and Ne/Nc if annual hunting mortality of males is high enough (>25–30%), and they concluded that reducing hunting mortality on males to keep breeding stag:hind ratios during the rut sufficiently high (≥18 stags:100 hinds) is important to maintain adequate Ne and, therefore, long-term adaptive potential. They also found that size-selective hunting is likely to result in only modest short-term evolutionary changes in life-history traits unless the annual harvest rate on males is high (>30%) or realized genetic variance components were large.

Coltman et al. (2) used a quantitative genetic analysis of a reconstructed pedigree for a wild population of Canadian bighorn sheep to show how hunting selection affected body weight and horn size. They showed that selection was most intense against rams with high breeding values because of hunter preference for large rams with large horns, with the consequence that breeding values for both ram traits declined steeply over 35 years. Because both traits are highly heritable and positively genetically correlated (2), continued selection against large rams with large horns is expected to directly reduce horn size with a correlated response in reduced body mass. Such selection will reduce the frequencies of these phenotypes to lower levels, with likely adverse consequences for male breeding success. Both ram weight and horn size are undoubtedly subject to sexual selection through male-male competition during the rut, but it is unclear to what extent such sexual selection can alter the rate of evolution under hunting selection because sexual selection gradients have not been estimated. However, they must be high for some heavily hunted populations, where heritabilities for traits under selection are high and observed temporal declines in breeding values for these traits are often substantial (e.g., ref. 2). Garel et al. (76) found similar patterns in morphology and life history resulting from trophy ram hunting in Europe.

Exploitation by Specimen Collectors

Understanding the response of consumers and hunters to perceived rarity is vital for predicting the impact of intervention strategies that seek to minimize extinction risk.

Hall et al. (77)

Another human activity that can impose exploitative selection on wild populations is specimen collecting, whether for private, commercial, or scientific use. The actions of collectors, which most commonly target vertebrates, such as tropical fishes, and invertebrates, such as arthropods and gastropods, could impose selection on wild populations through the removal of specimens conspicuous by their large size and appearance. Such selection is likely to be effective when populations are rare, phenotypes are dramatic, and opportunity for harvest by humans is substantial. Highly selective collection practices could affect the sustainability of these trades and the conservation of rare species (77, 78).

Terrestrial snails are one of the most imperiled groups in the world, and overcollecting has been one of the major threats to many of these species. For example, collecting of live tree snails (Liguus and Orthicalus spp.) found on isolated hardwood hammocks in the Florida Everglades began in the early 19th century and peaked in the 1940s before regulations were enacted because of conservation concerns (79). The loss of prized forms led collectors to translocate valuable morphs to places unknown to other snail collectors (79). In addition, collection of especially attractive morphs was competitive so that some attractive morphs were purposefully overcollected because they were more valuable when they became rare. Similarly, major snail collecting took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Hawaii, focusing on the brightly colored and variable Achatinellinae tree snails. Overcollecting did lead to extinctions, but it is unknown if there was any differential selective effects on morphs (80). In Moldova, Andreev (81) compared land snail (Helix pomatia) characteristics from exploited and unexploited sites and found that sites where land snails were exploited for food had much lower densities and a higher proportion of adult snails than sites that were not exploited. Specimen collecting can therefore provide an opportunity for selection that might reduce population viability.

Sexual Selection

Fishing techniques could remove certain sexes or sizes of squids, thus leading to “unnatural” sexual selection processes that affect recruitment.

Hanlon (82)

Sexual selection has been largely overlooked as a factor that can influence evolution under exploitation. In an important article, Hutchings and Rowe (28) concluded that the effects of fishing on the distributions of traits subject to sexual selection in an Atlantic cod life history could have a major impact on the rate and magnitude of fisheries-induced evolution. How mating systems influence the resistance of wild animals to collapse under exploitation and their ability to rebound when conditions improve remains an open question. Rowe and Hutchings (83) suggested that mate competition, mate choice and other components of mating systems are almost certain to have an impact on population growth rate at low levels of abundance. For example, if larger individuals enjoy greater reproductive success, sexual selection for increased body size could counter selection against larger size imposed by fishing.

Selective harvest can directly affect mating and have a strong effect on subsequent recruitment because it tends to remove individuals with particular characteristics, such as large size or elaborate weapons from those of the breeding pool (84). Hunting and fishing often impose direct selection against particular phenotypes by targeting individuals with sexually selected characters (e.g., antlers, horns, hooked jaws on salmon, or deep bodies). These activities can also indirectly alter sexual selection by affecting the distributions of traits under sexual selection (28, 82) by decreasing population size, or by favoring earlier maturation at the expense of later maturing individuals (e.g., ref. 17). In this way, exploitative selection can change both the means and variability of traits that determine mating and reproductive success. For example, reducing the maximum and compressing the variation in body size of breeding adults through exploitation is likely to change the dynamics of courtship and mate selection, and it might reduce overall mating success and productivity as well.

Harvest can also affect sexual selection by modifying the ratio of males and females available for mating. Hunting regulations for most mammal and bird species have traditionally favored greater harvest rates for males. Sex ratios of less than 1 adult male per 10 adult females are not uncommon in species where males are selectively hunted (52). Fishing also can produce biased sex ratios if one sex is larger than the other or is geographically more vulnerable to fishing (85). Theory predicts that the more abundant sex will become less choosy in mate choice and more aggressive in competition for mates (86).

Estimates of sexual selection in large mammals where some populations are subjected to hunting are relatively uncommon, but they evidently can be large. Sexual selection on male phenotypes is expected to be strongest when there is intense competition among males for mates, as when the operational sex ratio is highly skewed toward males (86). For example, Kruuk et al. (87) estimated large total (natural plus sexual) selection gradients on antler weight and leg length in unhunted male Scottish red deer. Lifetime breeding success was positively correlated with antler weight. In an elasticity path analysis that links selection gradients between phenotypes and components of fitness with the contributions of these components to population growth rate (mean absolute fitness), Coulson et al. (88) estimated selection gradients on a number of life history traits in unhunted red deer, including survival rates, birth date, and birth weight. They showed that, although many of them were statistically significant, most estimates varied widely over time, presumably in response to environmental and ecological factors that differ in importance in different years.

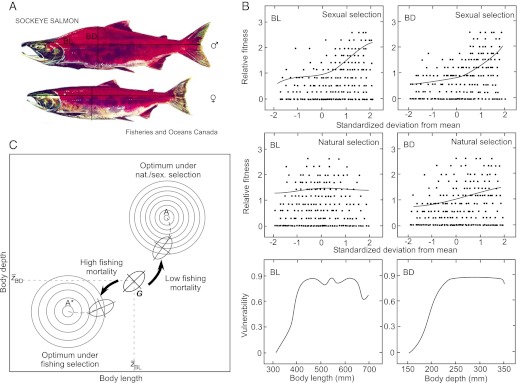

Some investigators have suggested that the effects of selection for smaller body size associated with fishing or hunting might be countered by sexual selection favoring larger individuals (28). Fig. 3 depicts a hypothetical example to illustrate how sexual and natural selection might affect evolution in response to exploitative selection in sockeye salmon. In this case, combined natural and sexual selection impose a selection gradient on a bivariate phenotype that opposes the selection gradient imposed by exploitation. As a result, a suboptimal phenotype in the wild breeding population can increase in frequency as the effectiveness of natural and sexual selection is reduced.

Fig. 3.

Potential consequences of natural, sexual, and fishing-induced selection in exploited sockeye salmon. (A) Typical morphological phenotypes for adult male and female sockeye salmon. BL, body length; BD, body depth. (B) Hypothetical relative fitness, as measured by reproductive success, among breeders that vary in body length and body depth. (Top) Sexual selection favors individual breeders with higher BL and BD phenotypes. (Middle) Natural selection favors individual breeders with intermediate BL and larger BD phenotypes. (Bottom) Individuals with larger values of BL and especially BD are more vulnerable to fishing mortality. (C) Potential evolution of the genetic covariance matrix (G) for the bivariate body length (BL)–body depth (BD) phenotype under combined natural, sexual, and fishing-induced selection. The box represents the bivariate adaptive landscape (in the sense of ref. 89). G is represented by the oval. Under natural and sexual selection on BL and BD in the absence of fishing, G will tend to move toward the “global” optimum bivariate phenotype A. When the population is subjected to substantial selective fishing mortality that targets potential breeders of larger BL and BD, G will tend to move toward the “local” alternative optimum bivariate phenotype A*. Natural and sexual selection impose a selection gradient on the bivariate phenotype, which tends to oppose the selection gradient imposed by selective fishing. The result is a suboptimal phenotype in the wild breeding population that might deviate substantially from A. Note the difference in elevation and steepness of fitness for the 2 alternative fitness optima.

Intense sexual selection can be common in populations of spawning salmon (90). The intensity of sexual selection might be diminished when fishing mortality is high because of reduced population sizes and human activities that have increased the cost of migration and changed the balance between natural and sexual selection. As migration becomes more difficult, individuals have less energy to devote to secondary sexual characteristics (91), which can further erode the strength of sexual selection beyond the effects related solely to smaller population size.

What are the possible long-term effects of reduced sexual selection that might ensue from continued exploitation? One possibility is reduced genetic quality of progeny resulting from relaxed sexual selection and reduced female mate choice (e.g., refs. 92 and 93). Pitcher and Neff (94) found in their breeding study of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) that additive and nonadditive genetic effects together increased survival of fish during early development by nearly 20%. They concluded that incorporating information on genetic quality of parents into breeding designs could increase survival by some 3 times over designs that exclude sexual selection processes by relying on random mating alone.

Implications

Several authors (2, 6, 14, 52) have recently emphasized that selection is an important but often ignored consequence of human exploitation of wild animals and that adaptation to exploitation can produce undesirable evolutionary change. Fisheries and wildlife management that does not incorporate evolutionary considerations is at risk of reducing wild productivity and eventual yield because exploitation removes phenotypes that might be those most favored by natural and sexual selection in the wild. Accounting for selection that is at odds with natural adaptive processes is therefore an important component of a comprehensive and effective sustainable management strategy. For this situation to change, at least 3 questions must be addressed: What are the primary genetic consequences of exploitation, and what is the evidence for them? Do these consequences influence demography in a way that would affect yield and concern managers? How effective can management be in detecting and countering these effects? Recently, promising strides have been made to address the first question but the evidence is still largely circumstantial (e.g., ref. 17). The other questions have seldom been addressed directly except through simulation (e.g., refs. 95 and 96).

Sustainable Harvest.

Sustainable exploitation requires that phenotypic changes induced by harvest do not appreciably reduce yield and viability. Although we cannot be certain that many of the observed phenotypic trends in a variety of exploited animals are solely the result of exploitative selection, it would be imprudent to assume that such selection has not had an effect. The coupling of such trends with evidence for reduced productivity and yield is reason enough to adopt a risk-averse approach in considering sustainable harvest practices. One means of maintaining viability is by reducing selectivity in exploitation; assuming that the level of exploitation is not so high that it poses excessive demographic risk, reducing selectivity ameliorates the potential for selection to erode viability through phenotypic evolution. It also maintains the opportunity for natural and sexual selection to maximize reproductive fitness. Sustainable harvest practices require adequate monitoring of traits that are sensitive to selection and influence viability (6), and promote management that maintains breeding populations that are large and diverse enough to foster the full range of phenotypes that natural and sexual selection can act on (28). Moreover, sustainable management strategies should adapt quickly and appropriately to detected changes (97).

Recovery.

Recovery after relaxation, or even reversal, of selective harvest is likely to be slower than the initial accumulation of harmful genetic changes (98). This is because harvesting can create strong selection differentials, whereas relaxation of this selective pressure will more often produce weaker selection in the opposing direction (99). de Roos et al. (100) used an age-structured fishery model to show that exploitation-induced evolutionary regime shifts can be irreversible under likely fisheries management strategies such as belated or partial fishery closure. Swain et al. (99) concluded that human-induced adaptation to fishing may be a primary reason for lack of recovery of northwest Atlantic cod because harvest has been reduced after the collapse of this fishery. This effect has been termed “Darwinian debt,” and has been suggested to have general applicability (19). That is, time scales of evolutionary recovery are likely to be much longer than those on which undesirable evolutionary changes occur. Conover et al. (101) provided the first experimental test of this expectation with laboratory populations of Menidia menidia. They found that the selective effects of fishing were reversible, but recovery took more than twice as many generations as the original period of fishery selection. Bromaghin et al. (95) and Hard et al. (96), in their simulation studies of Chinook salmon, found that complete recovery of size and age structures generally required 15–20 generations or more of substantial reductions in exploitation rate or no harvest at all. However, gene flow has the potential to accelerate the rate of recovery by restoring alleles or multiple-locus genotypes associated with the trait. For example, trophy hunting might reduce or eliminate alleles for large horn size, but gene flow from areas with no hunting might quickly restore alleles associated with large horn size (12).

No-take protected areas have considerable potential for reducing the effects both of loss of genetic variation and harmful exploitative selection. Models of reserves in both terrestrial (102) and marine (103) systems support this approach for a wide variety of conditions. However, the actual effectiveness of such reserves on exploited populations outside of the protected area depends on the amount of interchange between protected and nonprotected areas and on understanding the pattern and drivers of dispersal, migration, and genetic subdivision (104, 105). Some have suggested that as exploitation pressure intensifies outside protected areas, local protection could select for decreased dispersal distance and thereby increase isolation and fragmentation and potentially reduce the genetic capacity of organisms to respond to future environmental changes (106).

Acknowledgments.

We dedicate this article to Hampton Carson who failed through no fault of his own to convince FWA of the importance of sexual selection in the conservation of salmon. We thank Joel Berger, Steve Chambers, Dave Coltman, Roger Cowley, Doug Emlen, Marco Festa-Bianchet, Mike Ford, Roger Hanlon, Rich Harris, Wayne Hsu, Dan Jergens, Gordon Luikart, and Robin Waples for providing references and helpful comments. This article is based partially on work supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation Grant DEB 074218 (to F.W.A.) and by the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Sustainable Salmon Initiative Project 607 (to J.J.H.).

Footnotes

This paper results from the Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy of Sciences, “In the Light of Evolution III: Two Centuries of Darwin,” held January 16–17, 2009, at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center of the National Academies of Sciences and Engineering in Irvine, CA. The complete program and audio files of most presentations are available on the NAS web site at www.nasonline.org/Sackler_Darwin.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Jachmann H, Berry PSM, Immae H. Tusklessness in African elephants: A future trend. Afr J Ecol. 1995;33:230–235. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coltman DW, et al. Undesirable evolutionary consequences of trophy hunting. Nature. 2003;426:655–658. doi: 10.1038/nature02177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller RB. Have the genetic patterns of fishes been altered by introductions or by selective fishing? J Fish Res Bd Can. 1957;14:797–806. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Law R. Fisheries-induced evolution: Present status and future directions. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2007;335:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gjedrem Te. Selection and Breeding Programs in Aquaculture. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allendorf FW, England PR, Luikart G, Ritchie PA, Ryman N. Genetic effects of harvest on wild animal populations. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darwin C. The Voyage of the Beagle. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darwin C. The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life. New York: Mentor; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darwin C. The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. Vol. II. New York: D. Appleton; 1896. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous. Handle with care: Ecologists must research how best to intervene in and preserve ecosystems. Nature. 2008;455:263–264. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamon TR, Foote CJ. Concurrent natural and sexual selection in wild male sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka. Evolution. 2005;59:1104–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coltman DW. Evolutionary rebound from selective harvesting. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:117–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mace GM, Reynolds JD. In: Conservation of Exploited Species. Reynolds JD, Mace GM, Redford KR, Robinson J, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2001. pp. 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law R. Fishing, selection, and phenotypic evolution. ICES J Mar Sci. 2000;57:659–668. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milner JM, et al. Temporal and spatial development of red deer harvesting in Europe: Biological and cultural factors. J Appl Ecol. 2006;43:721–734. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darimont CT, et al. Human predators outpace other agents of trait change in the wild. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:952–954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809235106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hard JJ, et al. Evolutionary consequences of fishing and their implications for salmon. Evol Appl. 2008;1:388–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Festa-Bianchet M. In: Animal Behavior and Wildlife Conservation. Festa-Bianchet M, Appollonio M, editors. Washington, DC: Island; 2003. pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loder N. Point of no return. Conserv Pract. 2005;6(3):29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sogard SM, Berkeley SA, Fisher R. Maternal effects in rockfishes Sebastes spp: A comparison among species. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2008;360:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venturelli PA, Shuter BJ, Murphy CA. Evidence for harvest-induced maternal influences on the reproductive rates of fish populations. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2009;276:919–924. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan DS, Evermann BW. American Food and Game Fishes: A Popular Account of All the Species Found in America, North of the Equator, With Keys for Ready Identification, Life Histories and Methods of Capture. New York: Doubleday; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutter C. Natural history of the quinnat salmon. Investigation on the Sacramento River, 1896–1901. Bull U.S. Fish Commission. 1904;22:65–141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith VE. The Taking of Immature Salmon in the Waters of the State of Washington. Olympia, WA: State of Washington Department of Fisheries; 1920. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Handford P, Bell G, Reimchen T. A gillnet fishery considered as an experiment in artificial selection. J Fish Res Bd Can. 1977;34:954–961. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birkeland C, Dayton PK. The importance in fishery management of leaving the big ones. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:356–358. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenberg PB, Roy K. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of size-selective harvesting: How much do we know? Mol Ecol. 2008;17:209–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutchings JA, Rowe S. Consequences of sexual selection for fisheries-induced evolution: An exploratory analysis. Evol Appl. 2008;1:129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2007.00009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh MR, Munch SB, Chiba S, Conover DO. Maladaptive changes in multiple traits caused by fishing: Impediments to population recovery. Ecol Lett. 2006;9:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson SM, Seamons TR. A review of quantitative genetic components of fitness in salmonids: Implications for adaptation to future change. Evol Appl. 2008;1:222–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naish KA, Hard JJ. Bridging the gap between the genotype and the phenotype: Linking genetic variation, selection and adaptation in fishes. Fish Fish. 2008;9:396–422. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Araki H, Cooper B, Blouin MS. Genetic effects of captive breeding cause a rapid, cumulative fitness decline in the wild. Science. 2007;318:100–103. doi: 10.1126/science.1145621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beukema JJ. Angling experiments with carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) 1. Differences between wild, domesticated and hybrid strains. Neth J Zool. 1969;19:596–609. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biro PA, Abrahams MV, Post JR, Parkinson EA. Predators select against high growth rates and risk-taking behaviour in domestic trout populations. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2004;271:2233–2237. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biro PA, Stamps JA. Are animal personality traits linked to life-history productivity? Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Philipp DP, et al. Selection for vulnerability to angling in largemouth bass. Trans Amer Fish Soc. 2009;138:189–199. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falconer DS, Mackay TFC. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. 4th Ed. Harlow, UK: Longman Science and Technology; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ricker WE. Changes in the average body size and average age of Pacific salmon. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1981;38:1636–1656. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Law R, Rowell CA. In: The Exploitation of Evolving Resources. Stokes TK, McGlade JM, Law R, editors. Berlin: Springer; 1993. pp. 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinclair AF, Swain DP, Hanson JM. Measuring changes in the direction and magnitude of size-selective mortality in a commercial fish population. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2002;59:361–371. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hindar K, de Leaniz G, Koljonen M-L, Tufto J, Youngson AF. In: The Atlantic Salmon: Genetics, Conservation, and Management. Verspoor E, Stradmeyer L, Nielsen JL, editors. Oxford: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 299–324. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilborn R, Minte-Vera CV. Fisheries-induced changes in growth rates in marine fisheries: Are they significant? Bull Mar Sci. 2008;83:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamon TR, Foote CJ, Hilborn R, Rogers DE. Selection on morphology of spawning wild sockeye salmon by a gill-net fishery. Trans Amer Fish Soc. 2000;129:1300–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kendall NW, Hard JJ, Quinn TP. Quantifying six decades of fishery selection for size and age at maturity in sockeye salmon. Evol Appl. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2009.00086.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamon TR. Measurement of concurrent selection episodes. Evolution. 2005;59:1096–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fleming IA, Gross MR. Breeding competition in a Pacific salmon (Coho: Oncorhynchus kisutch): Measures of natural and sexual selection. Evolution. 1994;48:637–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ford M, Hard JJ, Boelts B, Lahood E, Miller J. Estimates of natural selection in a salmon population in captive and natural environments. Conserv Biol. 2008;22:783–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Policansky D. In: The Exploitation of Evolving Resources. Stokes TK, McGlade JM, Law R, editors. Berlin: Springer; 1993. pp. 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kingsolver JG, Pfennig DW. Patterns and power of phenotypic selection in nature. BioScience. 2007;57:561–572. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edeline E, et al. Trait changes in a harvested population are driven by a dynamic tug-of-war between natural and harvest selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15799–15804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705908104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rhodes OE, Jr, Smith MH. In: Wildlife 2001: Populations. McCullough D, Barrett R, editors. New York: Elsevier Science; 1992. pp. 985–996. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris RB, Wall WA, Allendorf FW. Genetic consequences of hunting: What do we know and what should we do? Wildl Soc Bull. 2002;30:634–643. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaillard J M, Loison A, Toigo C. In: Animal Behavior and Wildlife Conservation. Festa-Bianchet M, Appollonio M, editors. Washington, DC: Island; 2003. pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 54.FitzSimmons NN, Buskirk SW, Smith MH. Population history, genetic variability, and horn growth in bighorn sheep. Conserv Biol. 1995;9:314–323. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartl GB, Apollonio M, Mattioli L. Genetic determination of cervid antlers in relation to their significance in social interactions. Acta Theriologica. 1995;40(Suppl 3):199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moorcroft PR, Albon SD, Pemberton JM, Clutton-Brock TH. Density-dependent selection in a fluctuating ungulate population. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1996;263:31–38. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lukefahr SD, Jacobson HA. Variance component analysis and heritability of antler traits in white-tailed deer. J Wildl Manag. 1998;62:262–268. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mills LS. Conservation of Wildlife Populations: Demography, Genetics, and Management. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Voipio P. Evolution at the population level with special reference to game animals and practical game management. Papers on Game Research (Helsinki) 1950;5:1–175. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thelen TH. Effects of harvest on antlers of simulated populations of elk. J Wildl Manag. 1991;55:243–249. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryman N, Baccus R, Reuterwall C, Smith MH. Effective population size, generation interval, and potential loss of genetic variability in game species under different hunting regimes. Oikos. 1981;36:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez JG, Carranza J, Fernandez Garcia JL, Sanchez Prieto CB. Genetic variation of red deer populations under hunting exploitation in southwestern Spain. J Wildl Manag. 2002;66:1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mysterud A, Coulson T, Stenseth NC. The role of males in the dynamics of ungulate populations. J Anim Ecol. 2002;71:907–915. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wade MJ, Shuster SM. Sexual selection: Harem size and the variance in male reproductive success. Am Nat. 2004;164:E83–E89. doi: 10.1086/424531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clutton-Brock TH, Lonergan ME. Culling regimes and sex ratio biases in Highland red deer. J Appl Ecol. 1994;31:521–527. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kruuk LEB, Clutton-Brock TH, Albon SD, Pemberton JM, Guinness FE. Population density affects sex ratio variation in red deer. Nature. 1999;399:459–461. doi: 10.1038/20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bonenfant C, Gaillard J-M, Loison A, Klein F. Sex-ratio variation and reproductive costs in relation to density in a forest-swelling population of red deer (Cervus elaphus) Behav Ecol. 2003;14:862–869. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lande R, Barrowclough GF. In: Viable Populations for Conservation. Soulé ME, editor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1987. pp. 87–124. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elton CS. Voles, Mice, and Lemmings: Problems in Population Dynamics. Oxford: Clarendon; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haldane JBS. The selective elimination of silver foxes in Canada. J Genet. 1942;44:296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hartl GB, Reimoser F, Willing R, Koller J. Genetic variability and differentiation in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus L) of Central Europe. Genet Sel Evol. 1991;23:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Malo AF, Roldan ERS, Garde J, Soler AJ, Gomendio M. Antlers honestly advertise sperm production and quality. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2005;272:149–157. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martínez M, Rodriguez-Vigal C, Jones OR, Coulson T, Miguel AS. Different hunting strategies select for different weights in red deer. Biol Lett. 2005;1:353–356. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mysterud A, Tryjanowski P, Panek M. Selectivity of harvesting differs between local and foreign roe deer hunters: Trophy stalkers have the first shot at the right place. Biol Lett. 2006;2:632–635. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hard JJ, Mills LS, Peek JM. Genetic implications of reduced survival of male red deer Cervus elaphus under harvest. Wildl Biol. 2006;12:427–441. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garel M, et al. Selective harvesting and habitat loss produce long-term life history changes in a mouflon population. Ecol Appl. 2007;17:1607–1618. doi: 10.1890/06-0898.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hall RJ, Milner-Gulland EJ, Courchamp F. Endangering the endangered: The effects of perceived rarity on species exploitation. Conserv Lett. 2008;1:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Slone TH, Orsak LJ, Malver O. A comparison of price, rarity and cost of butterfly specimens: Implications for the insect trade and for habitat conservation. Ecol Econ. 1997;21:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Humes RH. A story of Liguus collecting: With a list of collectors 1744 to 1958. Tequesta. 1965;25:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hadfield MG. Extinction in Hawaiian Achatinelline snails. Malacologia. 1986;27:67–81. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Andreev N. Assessment of the status of wild populations of land snail (Escargot) Helix pomatia L. in Moldova: The effect of exploitation. Biodiv Conserv. 2006;15:2957–2970. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hanlon RT. Mating systems and sexual selection in the squid Loligo: How might commercial fishing on spawning squids affect them? CalCOFI Rep. 1998;39:92–100. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rowe S, Hutchings JA. Mating systems and the conservation of commercially exploited marine fish. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18:567–572. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kingsolver JG, et al. The strength of phenotypic selection in natural populations. Am Nat. 2001;157:245–261. doi: 10.1086/319193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vincent A, Sadovy Y. In: Behavioral Ecology and Conservation Biology. Caro T, editor. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1998. pp. 209–245. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Emlen ST, Oring LW. Ecology, sexual selection and the evolution of mating systems. Science. 1977;197:215–233. doi: 10.1126/science.327542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kruuk LEB, et al. Antler size in red deer: Heritability and selection but no evolution. Evolution. 2002;56:1683–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coulson T, Kruuk LEB, Tavecchia G, Pemberton JM, Clutton-Brock TH. Estimating selection on neonatal traits in red deer using elasticity path analysis. Evolution. 2003;57:2879–2892. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Simpson GG. The Major Features of Evolution. New York, NY: Columbia Univ Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Quinn TP. The Behavior and Ecology of Pacific Salmon and Trout. Seattle: Univ of Washington Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kinnison MT, Unwin MJ, Quinn TP. Migratory costs and contemporary evolution of reproductive allocation in male chinook salmon. J Evol Biol. 2003;16:1257–1269. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Drickamer LC, Gowaty PA, Christopher CM. Free female mate choice in house mice affects reproductive success and offspring viability and performance. Anim Behav. 2000;59:371–378. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Neff BD, Pitcher TE. Genetic quality and sexual selection: An integrated framework for good genes and compatible genes. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:19–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pitcher TE, Neff BD. Genetic quality and offspring performance in Chinook salmon: Implications for supportive breeding. Conserv Genet. 2007;8:607–616. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bromaghin JF, Nielson RM, Hard JJ. An investigation of the potential effects of selective exploitation on the demography and productivity of Yukon River Chinook salmon. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Technical Report 100. Anchorage, AK: US Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Region; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hard JJ, Eldridge WH, Naish KA. In: Sustainability of the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Salmon Fisheries: What Do We Know About Salmon Ecology, Management, and Fisheries? Krueger C, Zimmerman C, editors. Bethesda, MD: Alaska Sea Grant and American Fisheries Society; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuparinen A, Merilä J. Detecting and managing fisheries-induced evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2007;22:652–659. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Heino M. Management of evolving fish stocks. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1998;55:1971–1982. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Swain DP, Sinclair AF, Hanson JM. Evolutionary response to size-selective mortality in an exploited fish population. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2007;274:1015–1022. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Roos AM, Boukal DS, Persson L. Evolutionary regime shifts in age and size at maturation of exploited fish stocks. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2006;273:1873–1880. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Conover DO, Munch SB, Arnott SA. Reversal of evolutionary downsizing caused by selective harvest of large fish. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2009;276:2015–2020. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tenhumberg B, Tyre AJ, Pople AR, Possingham HP. Do harvest refuges buffer kangaroos against evolutionary responses to selective harvesting? Ecology. 2004;85:2003–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Baskett ML, Levin SA, Gaines SD, Dushoff J. Marine reserve design and the evolution of size at maturation in harvested fish. Ecol Appl. 2005;15:882–901. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kritzer JP, Sale PF. Metapopulation ecology in the sea: From Levins' model to marine ecology and fisheries science. Fish Fish. 2004;5:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Palumbi SR. Population genetics, demographic connectivity, and the design of marine reserves. Ecol Appl. 2003;13:S146–S158. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dawson MN, Grosberg RL, Botsford LW. Connectivity in marine protected areas. Science. 2006;313:43–44. doi: 10.1126/science.313.5783.43c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]