Summary

The cell biological phenomenon of autophagy (or “self-eating”) has attracted increasing attention in recent years. In this review, we first address the cell biological functions of autophagy, and then discuss recent insights into the role of autophagy in animal development, particularly in C. elegans, Drosophila and mouse. Work in these and other model systems has also provided evidence for the involvement of autophagy in disease processes, such as neurodegeneration, tumorigenesis, pathogenic infection and aging. Insights gained from investigating the functions of autophagy in normal development should increase our understanding of its roles in human disease and its potential as a target for therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

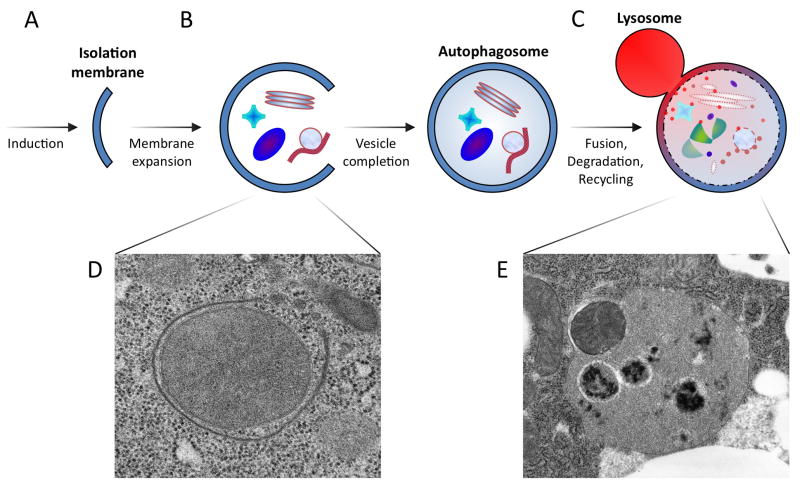

Autophagy is a ubiquitous catabolic process that involves the bulk degradation of cytoplasmic components through a lysosomal pathway. This process is characterized by the engulfment of part of the cytoplasm inside double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes. Autophagosomes subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form an autophagolysosome in which the cytoplasmic cargo is degraded (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of autophagy progression in metazoans.

(A) In response to starvation or other inductive cues, a membranous sac referred to as the phagophore or isolation membrane is nucleated from a poorly characterized structure known as the pre-autophagosomal structure or phagophore assembly site (PAS). (B) Expansion and curvature of the isolation membrane leads to engulfment of cytosolic material within the double membrane-bound autophagosome. The source of lipid contributing to this membrane growth has not been established. (C) Fusion of the autophagosomal outer membrane with lysosomes results in hydrolytic digestion of the inner membrane and the sequestered material, and export of the breakdown products into the cytoplasm. Prior fusion of autophagosomes with early or late endosomes (forming a structure known as an amphisome, not shown) may be required for autophagosome-lysosome fusion. (D–E) Electron micrographs of corresponding structures, including (D) a nearly completed autophagosome engulfing a mitochondrion, and (E) an auto-lysosome containing several degraded organelles and an intact mitochondrion.

Although this process was initially described over forty years ago (de Duve, 2005), two developments in the past decade have led to a substantial increase in interest and activity in the field of autophagy research. The first of these developments was a series of genetic screens in yeast that led to the discovery of the autophagy-related (ATG) genes that control this process (Harding et al., 1995; Thumm et al., 1994; Tsukada and Ohsumi, 1993). Orthologs to most of these ATG genes have now been identified in higher eukaryotes (Table 1), and genetic analyses have begun to decipher the functions of autophagy in multicellular organisms, such as nematodes, flies and mice.

Table 1.

Mutant phenotypes of autophagy-related genes in metazoans

| S. cerevisiae gene | Biochemical function | C. elegans ortholog | Drosophila ortholog | Mammalian ortholog | * LOF phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation of induction | ||||||

| TOR1, TOR2 | PIK-family Ser/Thr protein kinase, rapamycin target | let-363 | Tor | mTOR | AA, G, L, LL | (Blommaart et al., 1995; Hansen, 2008; Hansen et al., 2007; Hentges et al., 2001; Jia et al., 2004; Kapahi et al., 2004; Long et al., 2002; Noda and Ohsumi, 1998; Oldham et al., 2000; Scott et al., 2004; Vellai et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2000) |

| ATG1 | Ser/Thr protein kinase | unc-51 | Atg1 | ULK1, ULK2 | Aut, D, Egl, G, L, Nd, Scd, St, Unc, | (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Chan et al., 2007; Hedgecock et al., 1985; Matsuura et al., 1997; Meléndez et al., 2003; Ogura et al., 1994; Rubinsztein, 2006; Scott et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2004) |

| ATG13 | Phosphoprotein component of Atg1 complex | D2007.5 | CG7331 | KIAA0652 | ? | (Funakoshi et al., 1997; Meijer et al., 2007) |

| Vesicle nucleation | ||||||

| ATG6 | Component of Vps34 complex, BH3-like domain, Bcl-2 interacting protein | bec-1 | Atg6 | Beclin 1 | Ap, Aut, D, G, Nd, L, Scd, SL, Ster, T | (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Boya et al., 2005; Hansen, 2008; Jia et al., 2007; Jia and Levine, 2007; Kametaka et al., 1998; Kang et al., 2007; Meléndez et al., 2003; Qu et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2004; Seaman et al., 1997; Takacs-Vellai et al., 2005; Yue et al., 2003) |

| VPS34 | Class III PtdIns 3-Kinase | let-512 | Vps34/Pi3k59F | hVps34/PIK3C3 | Aut, L, SL | (Hansen, 2008; Juhasz et al., 2008; Kihara et al., 2001; Petiot et al., 2000; Roggo et al., 2002; Seglen and Gordon, 1982) |

| VPS15 | Ser/Thr protein kinase, component of Vps34 complex | ZK930.1 | Vps15/ird1 | hVps15/P150 | Aut, I | (Juhàsz et al., 2008; Kihara et al., 2001; Lindmo et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2007) |

| -- | Component of Vps34 complex, coiled-coil domain | -- | CG6116 | UVRAG | Aut, G, T | (Liang et al., 2006) |

| -- | Endophilin B1, BAR domain, component of Vps34 complex | erp-1 | endophilin B | Bif-1 | Aut, Scd, T | (Takahashi et al., 2007) |

| -- | WD40 domain, component of Vps34 complex | -- | -- | Ambra1 | Ap, Aut, G, L | (Fimia et al., 2007) |

| -- | Negative regulator of apoptosis, inhibits Beclin 1-Vps34 interaction | ced-9 | buffy | Bcl-2 | AA, Ap | (Hengartner and Horvitz, 1994; Pattingre et al., 2005; Quinn et al., 2003; Saeki et al., 2000) |

| Vesicle expansion | ||||||

| ATG3 | E2-like enzyme, conjugates PE to Atg8 | Y55F3AM.4 | Atg3/Aut1 | Atg3 | Aut, L, Scd | (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Ichimura et al., 2000; Juhasz et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2007; Tanida et al., 2002b) |

| ATG4 | Cysteine protease cleaves Atg8 C- terminus | ZK792.8, Y87G2A.3 | CG4428 | Atg4A-D/Autophagin1–4 | Aut, N, T | (Hemelaar et al., 2003; Kirisako et al., 2000; Marino et al., 2007; Thumm and Kadowaki, 2001) |

| ATG5 | Conjugated to Atg12 through internal Lys | atgr-5 | Atg5 | Atg5 | Ap, Aut, B, Cm, G, N, PL, Nd, Scd | (Boya et al., 2005; Hara et al., 2006; Hosokawa et al., 2006; Kametaka et al., 1996; Kuma et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Nakai et al., 2007; Qu et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2004) |

| ATG7 | E1-like enzyme, activates Atg8 and Atg12 | atgr-7 | Atg7 | Atg7 | Aut, D, Nd, Ox, Scd, SL, Std | (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Jia and Levine, 2007; Juhasz et al., 2007; Kim et al., 1999; Komatsu et al., 2006; Komatsu et al., 2005; Komatsu et al., 2007; Meléndez et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004) |

| ATG8 | Ubiquitin-like protein conjugated to PE | lgg-1, lgg-2 | Atg8a, Atg8b | LC3, GABARAP, GATE16 | Aut, D, Ox, Scd, SL | (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Hemelaar et al., 2003; Kirisako et al., 1999; Meléndez et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2007; Simonsen et al., 2008) |

| ATG10 | E2-like enzyme, conjugates Atg5 and Atg12 | D2085.2 | CG12821 | Atg10 | Ap, Aut | (Boya et al., 2005; Meléndez et al., 2003; Mizushima et al., 1998; Shintani et al., 1999) |

| ATG12 | Ubiquitin-like protein conjugated to Atg5 | lgg-3 | Atg12 | Atg12 | Ap, Aut, Scd, SL | (Boya et al., 2005; Hars et al., 2007; Mizushima et al., 1998; Scott et al., 2004; Tanida et al., 2002a) |

| ATG16 | Component of Atg5- Atg12 complex | K06A1.5, F02E8.5 | CG31033 | Atg16L1, Atg16L2 | Aut | (Mizushima et al., 2003; Mizushima et al., 1999; Rioux et al., 2007) |

| Recycling | ||||||

| ATG2 | Peripheral membrane protein, interacts with Atg9 | K01G5.10 | Atg2 | Atg2A, Atg2B | Aut, L, Scd | (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Scott et al., 2004; Shintani et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001) |

| ATG9 | Integral membrane protein, interacts with Atg2 | T22H9.2 | Atg9 | Atg9A, Atg9B | Aut | (Noda et al., 2000; Young et al., 2006) |

| ATG18 | Peripheral membrane protein, PI(3,5)P binding | atgr-18, Y39A1A.1 | Atg18/CG7986, CG11975, CG8678 | WIPI49/Atg18 | Aut, D, L, Nd, Scd | (Barth et al., 2001; Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Jia et al., 2007; Meléndez et al., 2003; Proikas- Cezanne et al., 2004; Scott et al., 2004) |

Phenotypes of gene inactivation: AA, autophagy activation; Ap, high incidence of cell apoptosis; Aut, Autophagy dysfunction; B, defective B cell development; Cm, Cardiomyopathy; D(+), normal dauer morphogenesis; D, abnormal dauer; Egl, egg laying defective; G, cell growth or proliferation; I, defective immune response; L, lethal; LL, long lifespan; N, modified Notch signaling; Nd, increased susceptibility to neurodegeneration; Ox, sensitive to oxidative stress; PL, postnatal lethality; Scd, suppression of cell death; SL, short lifespan; St, required for survival under starvation conditions; Ster, sterile; T, increased tumorigenesis; ?, unknown.

A second factor drawing investigators to this field is the growing awareness of the potential impact of autophagy on certain aspects of human health and disease, and the potential opportunity to develop novel therapies based on the manipulation of autophagy. Together, research into the basic cell biology of autophagy and its potential disease functions has revealed a substantial influence of autophagy on cellular physiology. For example, it is clear that autophagy plays an essential role in ridding the cell of damaged or superfluous organelles and proteins, in generating nutrients essential for cell survival under starvation and other stressful conditions, and in some cases acting as a cell death effector.

Given its role in these critical cellular functions, it would seem reasonable to expect that autophagy will have a significant impact on animal development, a process ultimately driven by changes in individual cell activity. Here, we discuss current concepts and recent findings regarding the cellular and developmental functions of autophagy. Although its role in development has yet to be fully defined, studies in model organisms have begun to describe a growing number of developmental processes that are influenced by autophagy, and are showing how this fundamental cellular process affects other cellular activities critical for development.

The molecular machinery of autophagy

The autophagic process can be divided into several distinct steps: signaling and induction, autophagosome nucleation, expansion and completion, autophagosome targeting, docking and fusion with the lysosome, and finally degradation and re-export of materials to the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). The molecular cascade that regulates autophagy and the mechanisms by which autophagy occurs have been the subject of recent, comprehensive reviews (Klionsky, 2007; Maiuri et al., 2007b; Mizushima and Klionsky, 2007; Yorimitsu and Klionsky, 2005) and thus are described only briefly below.

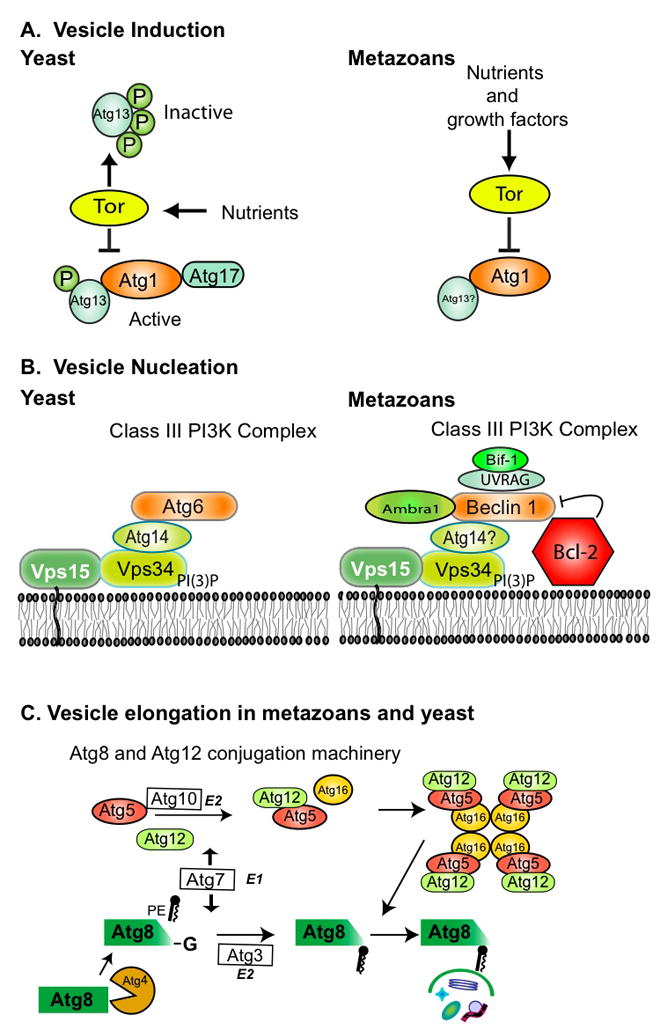

Autophagy occurs at basal levels in normal growing conditions, but can be dramatically upregulated by a number of stimuli, including starvation, hypoxia, intracellular stress, high temperature, high culture density, hormones and growth factors deprivation. The best characterized of these stimuli is nutrient starvation, which induces autophagy in part through the inactivation of the protein kinase target of rapamycin (Tor) (Fig. 2). In yeast, this inductive step includes the Atg1, Atg13 and Atg17 proteins, whose association is regulated by TOR-dependent signaling (Fig. 3). Atg1 also appears to be a target of TOR signaling in higher eukaryotes (Scott et al., 2007), suggesting that this mechanism is widely conserved.

Figure 2. Nutrient-dependent regulation of autophagy.

Autophagy proceeds constitutively at a low basal rate in most cells, and can be induced to high levels in response to starvation, loss of growth factor signaling, and other stressors. The TOR signaling pathway plays a central role in many of these responses. The kinase activity of TOR is inhibited by Tsc1 and Tsc2, which form a complex with GAP activity against the small GTPase Rheb, a direct activator of TOR (Wullschleger et al., 2006). The Tsc1/Tsc2 complex in turn is regulated by several upstream protein kinases, including Akt in response to insulin signaling and AMPK in response to AMP/ATP levels. Downstream of TOR, the protein kinases Atg1 and S6K have important roles in autophagy, but the relevant substrates of these kinases have not been determined (Kamada et al., 2000; Scott et al., 2004). In addition, both Atg1 and S6K inhibit TOR signaling through negative feedback loops (Lee et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2007). Signaling levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in response to starvation and are required for activation of the autophagy-specific protease Atg4 (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007). Starvation also inhibits the association of Beclin 1/Atg6 with Bcl-2, leading to increased autophagic activity of Beclin 1 (Pattingre et al., 2005). Abbreviations: AMP, adenosine monophosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; GAP, GTPase activating protein; S6K, p70 S6 kinase; Tsc, tuberous sclerosis complex.

Figure 3. Evolutionary conservation of the molecular machinery of autophagy.

The initial formation of the autophagosome can be divided into distinct steps: (A) induction, (B) vesicle nucleation, and (C) vesicle elongation. (A) In yeast, Tor controls the phosphorylation (P) state of Atg13, a protein required for autophagy. Inhibition of Tor causes the dephosphorylation of Atg13 and the subsequent formation of a complex containing Atg1, Atg13, Atg17 and several other proteins, which in turn induces autophagy. Orthologs of Atg13 and Atg1 have been identified in metazoans, but no ortholog to Atg17 has been identified. In metazoans, Tor similarly inhibits autophagy, but whether this is through an interaction between Atg1 and Atg13 or an equivalent protein to Atg17 is not known. (B) The vesicle nucleation step (the formation of the isolation membrane/phagophore) results from the activity of a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K/Vps34) complex, which localizes other pre-autophagosomal proteins to the phagophore. In mammals, Bcl-2, UVRAG, and Bif 1 are part of this complex. Orthologs to all three proteins exist in Drosophila and C. elegans. (C) The vesicle expansion of the phagophore into an autophagosome results from the concerted action of two novel and highly conserved ubiquitin-like conjugation pathways, the Atg12 conjugation system (Atg12p, Atg5p, and Atg16p), and the Atg8 lipidation system (Atg8, Atg3, and Atg7). These pathways function in mice, however, it is not known whether the same multimeric structures occur in all metazoans.

A second functional complex involved in the vesicle nucleation step consists of the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase Vps34, Atg6/Vps30, and several associated factors (Fig. 3B). Two distinct Vps34/Atg6 complexes have been described in yeast (Kametaka et al., 1998): an autophagy-specific complex that is thought to localize other autophagy proteins to the pre-autophagosomal structure or phagophore assembly site (PAS), and a second complex involved in vacuolar protein sorting. Likewise in metazoans, Vps34 participates in both autophagy and other vesicle trafficking processes, most likely via its assembly into distinct complexes (Zeng et al., 2006). Interestingly, C. elegans BEC-1, and human Beclin1, the ATG6 orthologs, can complement the autophagy, but not the VPS, function of ATG6 in yeast (Meléndez et al., 2003), suggesting that there are functional differences between metazoan and yeast ATG6.

Two novel and highly conserved ubiquitin-like conjugation pathways, the Atg12 conjugation system (consisting of a complex of Atg12p, Atg5p, and Atg16p), and the Atg8 lipidation system (consisting of Atg8, Atg3, and Atg7) (Fig. 3C) mediate vesicle expansion and vesicle completion (Mizushima, 2007; Ohsumi, 2001; Suzuki and Ohsumi, 2007). These conjugation systems are widely conserved in eukaryotes and have an essential role in autophagy.

Once the autophagosome is completed, it is transported to the lysosome (or the vacuole in yeast) in a dynein-dependent manner, and the outer membrane of the autophagosome fuses with the lysosomal membrane using fusion machinery that is not specific to the autophagic pathway. The subsequent breakdown of the internal autophagosomal membrane allows acidic lysosomal hydrolases to access the cytosolic cargo, leading to its degradation and, ultimately, to its recycling.

Cellular functions of autophagy

Starvation survival

One of the best understood and perhaps most fundamental cellular roles of autophagy is to provide an internal source of nutrients under starvation conditions. In most cell types, nutrient withdrawal elicits a robust stimulation of autophagy, and this can significantly extend the survival time of yeast and cultured mammalian cells in the absence of nutrients. Indeed, many yeast ATG genes were first identified through screens for starvation sensitivity (Tsukada and Ohsumi, 1993). Apoptosis-deficient Bax−/− Bak−/− mouse bone marrow cells can remain viable for several weeks in the absence of IL3, which is essential for nutrient uptake in these cells; disruption of autophagy under these conditions results in rapid cell death (Lum et al., 2005a). In mammalian cells with an intact apoptotic system, such as in mouse embryonic fibroblasts or HeLa cells, the genetic or pharmacological inhibition of autophagy also significantly accelerates starvation-induced death (Boya et al., 2005). Under normal conditions in vivo, autophagy likely acts as a buffer against fluctuations in exogenous nutrient availability, maintaining intracellular nutrient concentrations at a relatively constant level.

How do the nutrients liberated by autophagy promote survival during starvation? The death of autophagy-deficient IL3-deprived Bax−/− Bak−/− mouse cells can be prevented by the addition of methylpyruvate (Lum et al., 2005b), a cell-permeable substrate of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in mitochondria, indicating that autophagy-derived nutrients have a critical role in ATP production. In addition, in starved Atg mutant yeast cells, the intracellular level of free amino acids drops significantly, becoming limiting for protein synthesis (Onodera and Ohsumi, 2005). Thus, nutrients derived from autophagy can be essential for both energetic and biosynthetic functions.

In addition to providing these functions cell autonomously, autophagy-derived nutrients can be exported out of the cell to support peripheral tissues. Accordingly, fasting induces a more severe reduction of plasma amino acid concentrations in Atg5−/− mice than in controls (Kuma et al., 2004). Thus, in multicellular organisms, autophagy helps to maintain extracellular nutrient levels within a narrow limit compared to the wider range faced by single celled organisms or cells grown in culture. Nonetheless, the finding that fasting leads to the induction of autophagy in most of the tissues of transgenic mice that express the autophagosome marker GFP-Atg8 (a notable exception being cells of the CNS) (Mizushima et al., 2004) indicates that despite the buffering effects of autophagy, the magnitude of extracellular nutrient fluctuation in animals can be considerable.

Organelle turnover and cellular renewal

Although autophagy is most evident following starvation, a basal level of constitutive autophagy appears to be a universal feature of nearly all eukaryotic cells. One important function of basal autophagy is to rid the cell of defective or superfluous organelles, and autophagy would appear to be the sole cellular process by which this occurs. Mitochondria accumulate oxidative damage with age, and, in atg mutants, such damaged mitochondria fail to be eliminated and accumulate to high levels (Kim and Sun, 2007; Zhang et al., 2007). Defective mitochondria also appear to be a significant source of reactive oxygen species, leading to genotoxic damage in atg mutant cells, which may partially explain the potential tumor suppressive effects of autophagy (Mathew et al., 2007). Both the random and selective incorporation of mitochondria into autophagosomes can contribute to this process (Kissova et al., 2007), sometimes referred to as mitophagy. Conditions that lead to mitochondrial damage cause a strong induction of mitophagy, and, indeed, mitophagy might have a confounding effect on chemotherapeutic agents that function through mitochondria-dependent damage in metabolically active cells (Amaravadi et al., 2007).

The life cycle of other organelles can be similarly influenced by autophagy. Induction of the unfolded protein response pathway in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) results in the activation of autophagy and in the engulfment of portions of the ER (Hoyer-Hansen and Jaattela, 2007). This autophagic response is critical for surviving ER stress, although sequestration of the ER into autophagosomes without subsequent lysosomal degradation might be sufficient for protection in some cases (Bernales et al., 2006). Selective autophagy also plays a key role in eliminating excess peroxisomes in yeast and mammalian cells following removal of peroxisome-proliferating drugs or media (Iwata et al., 2006; Sakai et al., 2006).

In addition to these effects on organelles, basal autophagy also plays a key role in eliminating misfolded, aggregated or otherwise damaged proteins, which may be resistant to degradation by the ubiquitin-proteosome system. Indeed, ubiquitinated protein aggregates accumulate in atg mutant mouse hepatocytes and neuronal cells (Hara et al., 2006; Juhasz et al., 2007; Komatsu et al., 2005), and autophagy can suppress neurodegenerative phenotypes caused by the expression of aggregate-prone proteins in various fly, nematode and mouse neurodegeneration models (Florez-McClure et al., 2007; Jia et al., 2007; Ravikumar et al., 2004). Interestingly, the inhibition of proteosome function can lead to an increased rate of autophagy, indicating that communication occurs between these two, major, degradative pathways (Ding et al., 2007). Together, the turnover of organelles and macromolecules through basal autophagy plays a major role in cell renewal and viability, and the upregulation of this process is critical to surviving cellular insults and stresses. The activation of autophagy in response to fasting may further boost this renewal effect, and may contribute to the anti-aging effects of caloric restriction (Bergamini et al., 2004).

Cell death

Seemingly at odds with its role in promoting cell survival, autophagy is often observed at high levels in dying cells, and in some cases might actively contribute to cell death. Also referred to as type II programmed cell death, autophagic cell death is distinguished from type I (apoptotic) cell death by the presence of abundant autophagic structures in the dying cell, a lack of phagocyte recruitment, and, in some instances, by caspase independence (Baehrecke, 2005; Schweichel and Merker, 1973). It is unclear whether autophagy provides the killing mechanism in such cells, or whether it represents a failed attempt at survival or the elimination of cell debris. Nonetheless, the disruption of autophagy can block the death of cultured cells with disabled apoptotic machinery (Shimizu et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004), and to impair or delay developmental cell death in Drosophila (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Juhasz et al., 2007), as discussed further below. In addition, the induction of high levels of autophagy can be sufficient to cause cell death (Kang et al., 2007; Pattingre et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2007). Although the mechanisms by which autophagy leads to cell death are unclear in most cases, they may involve the targeted destruction of factors required for cell survival (Yu et al., 2006). Future studies are required to understand the different contexts under which autophagy can promote either cell survival or destruction.

Cell growth

It has long been noted that there exists an inverse correlation between rates of autophagy and cellular growth. For example, most conditions that stimulate autophagy, such as starvation, growth factor withdrawal, and rapamycin treatment, result in reduced cell growth (Neufeld, 2004). Furthermore, many negative regulators of autophagy are growth-promoting oncoproteins, whereas positive regulators are often tumor suppressors (Botti et al., 2006). While these correlative data may simply reflect regulatory pathways that are common to autophagy and cell growth, they are also consistent with a mechanism by which autophagy inhibits cell growth under growth-suppressive conditions. Consistent with this model, in studies of cultured mouse embryonic fibroblasts and Drosophila larvae, it has been recently found that Atg mutant cells do not undergo a normal reduction in cell growth rate in response to starvation or rapamycin (Hosokawa et al., 2006; Scott et al., 2007). It was also shown that the overexpression of Atg1 leads to the induction of autophagy and to sharply reduced cell growth. These results indicate that autophagy likely contributes to the reduced rate of cell growth in response to certain growth inhibitory signals. Whether this results from the general catabolic nature of autophagy, or reflects the selective degradation of growth-promoting proteins or organelles has not been determined.

Functions of autophagy in development

Is autophagy essential for normal development?

It is clear that autophagy has many important cellular functions, many of which are involved in development. What is the evidence that autophagy plays a role in development, and through which cellular function does autophagy influence a given developmental process? Surprisingly, genetic studies in mice, flies and worms have found that while some mutations in genes essential for autophagy result in embryonic lethality, other mutants with strong autophagy phenotypes remain viable through embryogenesis, with defects becoming apparent only postnatally or in adulthood.

In C. elegans, bec-1 homozygous animals, derived from bec-1 heterozygous parents, exhibit a highly penetrant lethal phenotype; they arrest at various stages of development, exhibiting the formation of cellular vacuoles, uncoordinated phenotypes, and molting defects (Takacs-Vellai et al., 2005). Mutant bec-1 animals that reach adulthood are sterile. Thus, bec-1 activity is required for viability and fertility. Worms that carry a mutation in the BEC-1 partner protein, the Class III PI-3 kinase, Vps34, (C. elegans ortholog is let-512), also display a lethal phenotype (Roggo et al., 2002). In addition, RNAi-mediated knockdown of two other C. elegans atg orthologs (Atg8/lgg-1, and Atg18/F41E6.13) result in early developmental arrest, during or before the first larval stage (Meléndez et al., 2003). In contrast, the C. elegans Atg1 ortholog unc-51 is dispensable for embryonic development, despite playing an essential role in autophagy. Mutations in unc-51 result in adults with an uncoordinated phenotype, and axons of the mutant animals display abnormal vesicles and membrane cisternae (Hedgecock et al., 1985; McIntire et al., 1992). These results indicate that different autophagy genes may play distinct roles during embryonic development or that some genes display partial redundancy.

A similar conclusion can be drawn from genetic studies in flies and mice. In Drosophila, null mutations in Atg1 result in fully penetrant lethality late in the pupal stage, just prior to eclosion (Scott et al., 2004). Earlier lethality at the larval stage is observed in animals carrying mutations in the Drosophila Atg18 or Atg6 genes. Mutations in beclin 1 also disrupt embryonic development in the mouse, resulting in severely reduced growth at embryonic day (E) 7.5 and death by E8.5 (Yue et al., 2003). In contrast, flies with mutations in Drosophila Atg7 or Atg8a develop to adulthood, and mice with mutations in Atg4C, Atg5, Atg7, or Bif-1 progress through embryonic development in normal numbers, although in each of these cases, serious defects are observed postnatally (see below) (Juhasz et al., 2007; Komatsu et al., 2005; Kuma et al., 2004; Marino et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2007; Simonsen et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2007).

The mechanistic basis for this broad range of Atg mutant phenotypes in these genetic model organisms is poorly understood, in part due to our incomplete understanding of the cellular focus of the lethality. We also do not understand to what extent potential embryonic phenotypes may be masked by maternally contributed mRNA or protein, nor at what stages of development these maternal supplies may be depleted in each case. Overall, these findings suggest that autophagy plays somewhat subtle or redundant roles during development, or that defects in autophagy can be compensated for by the activation of other cellular processes. In addition, the range of mutant phenotypes indicate that some Atg genes have additional roles in other essential cellular functions. For example, Atg1/UNC-51 is involved in endocytic processes in the neurons of mice and worms, and mammalian Beclin 1 interacts with members of the Bcl-2 family, suggesting a potential role in apoptosis (Liang et al., 1998; Tomoda et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2007).

In some cases, the connection between a specific cellular function of autophagy and a given developmental process is straightforward. For example, the final stages of erythrocyte maturation occur through direct autophagic elimination of mitochondria and other organelles (Fader and Colombo, 2006; Schweers et al., 2007). Other less extreme examples of this type of cellular remodeling are likely to contribute widely to cell differentiation. However, in many cases, the mechanisms by which autophagy contributes to development are less clear and may be indirect, and more than one cellular function of autophagy may be at play. Below we discuss recent studies of development-related phenotypes of autophagy mutants in three specific areas stress adaptation, cell death, and neuronal development - emphasizing the underlying cellular mechanisms where known.

Adaptation to starvation and stress

A role for autophagy in C. elegans development was first provided by studies of dauer morphogenesis (Meléndez et al., 2003). C. elegans larvae respond to unfavorable environmental conditions (e.g. starvation, high population density, increased temperature) by arresting in an alternative third larval stage, referred to as the dauer diapause (Cassada and Russell, 1975; Riddle, 1997). Dauer larvae are characterized by radial constriction and elongation of the body and pharynx, resistance to detergent (sodium dodecyl sulfate or SDS) treatment, hyperpigmentation of the intestinal granules, increased fat accumulation, long lifespan and the ability to exit the dauer stage if the environmental conditions improve. The control of dauer development in C. elegans shares similarities with the induction of autophagy in other eukaryotes. Environmental cues, such as temperature, starvation, and high population, are potent inducers of autophagy in yeast, Dictostyelium and mammals, and also induce dauer formation in C. elegans. Dauer development is regulated by different signaling pathways that also regulate fat storage, longevity, reproduction, and stress responses, including the insulin/IGF-1, the transforming growth factor (TGF-β) and the cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathways (Barbieri et al., 2003; Patterson and Padgett, 2000; Raizen et al., 2006). In dauer constitutive daf-2 (the insulin/IGF-1 receptor) mutants, an increase in autophagy occurs as noted by the localization of GFP::LGG-1 into discrete punctate structures in hypodermal seam cells (a cell required for multiple aspects of dauer morphogenesis) (Meléndez et al., 2003). This autophagy induction is required for dauer morphogenesis, since most daf-2 mutant animals that are grown at dauer-inducing temperature and in which bec-1, unc-51/Atg1, atgr-7, lgg-1/Atg8, and atgr-18 were individually knocked down by RNAi fail to complete normal dauer development (Meléndez et al., 2003). These animals lack the characteristics associated with dauer: they do not undergo pharyngeal and total body constriction and elongation, have less fat accumulation, are not resistant to SDS, die within a few days, and fail to resume normal development when transferred to the non-dauer-inducing temperature. Autophagy is also required for dauer formation that is triggered by the lack of daf-7/TGF-β (Meléndez et al., 2003). Together, these data suggest that autophagy genes act downstream of insulin/IGF-1 and TGF-β signaling, that autophagy is required for the normal process of dauer morphogenesis, and that autophagy may be required for the cellular and tissue remodeling that permits C. elegans to successfully adapt to environmental stress. How autophagy is regulated during dauer formation is not known. Whether autophagy, in addition to its role in dauer morphogenesis, is required for dauer survival and/or dauer recovery is also unknown.

The autophagic machinery has been shown to directly promote organismal survival during starvation. Using animals that express the autophagy marker GFP::LGG-1 in the pharynx (see Box 1), Kang et al. have shown that starvation activates autophagy in the pharyngeal muscle (Kang et al., 2007). Interestingly, a deficiency in the levels of autophagy, caused by either a partial knockdown of bec-1 or of atgr-7, promotes the death of starved animals. The decrease in pharyngeal pumping that occurs in knockdown bec-1 animals can be attenuated by giving them food. A correlation between pumping efficiency and survival suggests that autophagy may provide the energy that is essential to maintain pharyngeal pumping efficiency and to ensure organismal survival during starvation. Whether autophagy is induced in other tissues in response to starvation is not yet known. In mammals, other muscle cells may also undergo autophagic catabolism to generate nutrients in order to maintain the health of neurons and other vital tissues.

Box 1. Detection of autophagy in vivo.

Several methods are used to monitor the progression of autophagy in vivo. Autophagy is classically detected by electron microscopy. In electron micrographs, autophagosomes are characterized by a double-membrane that surrounds sequestered cytoplasmic material. The discovery that Atg8 and its metazoan orthologs become stably associated with the autophagosomal membrane led to the development of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Atg8 molecules as effective and reliable ways of monitoring autophagy in nematodes, flies and mammals (Kabeya et al., 2000; Meléndez et al., 2003; Mizushima et al., 2004). The induction of autophagy in living animals can be detected by the localization of Atg8 (and its mammalian and C. elegansorthologs, LC3 and LGG-1, respectively) to punctate dots, in contrast to a diffuse cytoplasmic localization observed in the absence of autophagy.

GFP-LC3 has been used to detect autophagosomes through direct fluorescence microscopy both in mammalian cultured cells and in mice in vivo. In the figure, panel A shows GFP-LC3-labeled autophagosomes between myofibrils in the muscle tissues from mice after 48 h of starvation (asterisks indicate nuclei, adapted from Mizushima et al. 2004).

In C. elegans, GFP fusions to the Atg8 ortholog LGG-1 have been used to detect autophagy in most developing tissues (Meléndez et al., 2003). Induction of autophagy by starvation, inactivation of Tor, and during dauer development is marked by the punctate localization of GFP-LGG-1 in hypodermal seam cells, a cell type known to be important for certain dauer-associated morphological changes (Hansen, 2008; Meléndez et al., 2003). Panel B shows GFP::LGG-1 expression in the hypodermal seam cells of daf-2 mutant animals that have an increase in autophagy (arrow shows representative GFP-positive punctate areas, modified after Meléndez et al., 2003). In C. elegans, inactivation of autophagy genes results in an aberrant localization of GFP-LGG-1 to large aggregates, presumably due to ineffective clearance of LGG-1 through the autophagolysosomal pathway (Meléndez et al., 2003).

In Drosophila, GFP-Atg8 can be used to monitor both starvation-induced autophagy as well as the developmental induction of autophagy in the larval fat body toward the end of the larval period (arrow-head in C shows a representative autophagosome; Rusten et al., 2004; Scott et al., 2004). Inactivation of autophagy genes in Drosophila results in a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern of GFP-Atg8 under starvation conditions similar to that observed in the absence of autophagy (Juhasz et al., 2007). In the absence of high levels of autophagy, GFP-Atg8 often accumulates in the nucleus. In addition, the expansion of the lysosomal system in response to autophagy induction in the Drosophila fat body can be followed using Lysotracker dyes.

An important point when detecting autophagy in vivo is that autophagy is a dynamic process that can be positively or negatively regulated. Thus, accumulation of autophagosomes may reflect induction of autophagy, or reduced turnover of autophagosomes. Other strategies for detecting autophagy biochemically include: determining the static or flux-dependent lipidation state of Atg8 (Atg8-II/Atg8-I) by western blot analysis; measuring the degradation of long-lived protein by pulse-chase labeling; and determining the levels of selective autophagy substrates. See Klionsky et al. (2008) for further discussion of this topic.

Although the developmental response to starvation in Drosophila is quite distinct from that of C. elegans, autophagy has an important role in the survival of stress and starvation in the fly, and at least some of the genetic circuitry appears to be conserved. The larval fat body is a nutrient storage organ that contains large deposits of lipid and glycogen, somewhat analogous to the vertebrate liver. Drosophila larvae can survive several days in the complete absence of nutrients, and two or more weeks in the absence of amino acids (Britton and Edgar, 1998). During these periods of starvation, nutrients are mobilized from the fat body to support the imaginal tissues, which are destined to give rise to adult structures of the fly. This starvation-induced mobilization occurs in large part through autophagy, and indeed autophagy-defective Drosophila mutants die more rapidly under starvation conditions (Juhasz et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2004). Like dauer development in C. elegans, this starvation response occurs through the downregulation of insulin/IGF and TOR signaling, and constitutive activation of these pathways prevents the induction of autophagy by starvation and leads to starvation hypersensitivity (Britton et al., 2002; Scott et al., 2004). Paradoxically, the downregulation of TOR signaling in response to starvation leads both to the induction of autophagy and to the reduced activity of S6K, a substrate of TOR that is required for autophagy (Scott et al., 2004). This self-limiting feature of the TOR pathway may prevent autophagy from reaching excessive levels during chronic starvation. Autophagy also appears to promote Drosophila survival against a number of additional stressors, including oxidative stress, chill-induced coma and CO2 anesthesia (Juhasz et al., 2007).

Autophagy also plays a critical role in stress responses in mammals, and is required for starvation survival during postnatal development in the mouse (Komatsu et al., 2005; Kuma et al., 2004). Newborn mice experience an early period of starvation just after birth, due to the lack of placental nutrient supply. This early starvation induces autophagy in various neonatal tissues, such as the heart, lung and pancreas. In the absence of Atg5 or Atg7 function, mice do not survive the period of neonatal starvation and die within a day after birth (Komatsu et al., 2005; Kuma et al., 2004). Mutant mice deficient for the Atg4C gene progress to adulthood, possibly due to the activity of other Atg4 gene family members, but show a reduction in locomotor activity under prolonged starvation, and an increased susceptibility to chemical carcinogens (Marino et al., 2007). Similarly, in mice carrying a disruption of the Bif-1 gene, which encodes a critical component of the Beclin 1-Vps34 complex, early development appears normal, but adult mutant mice display enlarged spleens and an increased incidence of spontaneous tumors (Takahashi et al., 2007).

In each of these examples, we have only a dim appreciation of the cellular functions and cell-specific requirements that are supported by autophagy. In autophagy-defective newborn mice, plasma concentrations of amino acids are significantly reduced, and these animals display electrocardiograms consistent with a shortage of respiratory substrates (Kuma et al., 2004). Thus general defects in energy metabolism may be the immediate cause of the premature death of Atg5− and Atg7 null mice, although other abnormalities observed in these mutants, such as suckling defects and ubiquitin-positive cytoplasmic inclusions (Komatsu et al., 2005), are consistent with their having additional problems earlier in development. The role of autophagy in dauer formation in C. elegans is likely to be more complicated, given the involvement of multiple cell types and physiological responses in this process. Autophagy is likely to serve as a critical source of the nutrients and energy that are necessary for the extensive morphogenetic changes that occur during dauer development. In addition, autophagy may directly contribute to cellular remodeling by eliminating superfluous cytoplasmic components, and may influence the survival of specific cell types. Mosaic analysis of autophagy mutants may help to identify cell types with special requirements for autophagy in these developmental processes.

Neuronal development

An exclusive role for autophagy in mouse neuronal development has been reported for the Ambra1 (activating molecule in Beclin1-regulated autophagy) protein (Fimia et al., 2007). Ambra1 was identified in a gene-trap approach in mice to find genes expressed in the developing nervous system. Cecconi and colleagues have shown that Ambra1 interacts with Beclin 1 in vivo, and regulates Vps34-dependent autophagy. As in Beclin 1 in vitro studies, overexpression of Ambra1 in human fibrosarcoma cells leads to constitutively high levels of autophagy and to decreased cell proliferation. Furthermore, downregulation of Ambra1 impairs the interaction between Beclin 1 and Vps34. Ambra1 null mutant mice display embryonic lethality (starting from E14.5) that is characterized by severe neural tube defects, associated with an impairment in the autophagy pathway, an excess in programmed cell death, an increase in cell proliferation, and an accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. However, no defects in neuronal specification were detected (Fimia et al., 2007). Hyperproliferation is the earliest detectable abnormality in the developing neural tubes of these mutant embryos, followed by a wave of caspase-dependent apoptosis, indicating that there is a complex interplay between autophagy, the regulation of cell survival and the regulation of cell proliferation in mammals. Interestingly, hyperproliferation is observed in response to the disruption of any of several components of the Beclin 1/Vps34 complex in mammalian cells, including Beclin 1, Ambra1, UVRAG or Bif-1. This phenotype is not observed in other autophagy mutants, indicating that the disruption of this complex results in a distinct autophagy defect that leads to increased proliferation, or that this complex has a growth suppressive function that is separate from its role in autophagy. Once again, the cellular basis for the developmental phenotypes of Ambra1 mutants is unclear, although the increased rate of cell proliferation and death are consistent with defective turnover of an oncogenic factor(s). The restriction of the Ambra1 phenotype to neurons suggests that other factors may supplant its role in non-neuronal tissues.

A role for autophagy in the clustering of neurotransmitter receptors in development has been reported in C. elegans (Rowland et al., 2006). The clustering of neurotransmitter receptors results from signaling events during development that are initiated when presynaptic terminals are contacted by the postsynaptic cell. In C. elegans, body-wall muscles are innervated by both GABA and non-GABA neurons (White, 1986). GABA terminals organize GABAA receptors into synaptic clusters, which are internalized and degraded, as long as they lack presynaptic input. This degradation of GABAA receptors is specifically mediated by an autophagic pathway, while that of acetylcholine receptors in the same cells is not (Rowland et al., 2006). Curiously, the mammalian GABAA-receptor-associated protein GABARAP is an ortholog of the yeast autophagy protein Atg8p (two other mammalian orthologs of Atg8p are LC3 and GATE16, see Table 1), which may hint at a potentially regulatory role of autophagy in balancing neuronal excitation and inhibition (due to selective GABAA receptor degradation). These findings show an unexpected degree of specificity and a novel function for autophagy in the degradation of neuronal cell surface receptors. Similar mechanisms of selective receptor degradation by autophagy may also be at play to regulate cellular growth, differentiation, and development.

Programmed cell death

The developmental process of insect metamorphosis involves the wholesale death and elimination of a substantial portion of the larval body, providing both space and nourishment for imaginal tissues as they are reorganized into their adult form inside the pupal case. Destruction of larval structures such as the Drosophila salivary gland and digestive tract is triggered by a sharp rise in the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone, and is associated with a dramatic upregulation of autophagy prior to and during cell death. This process has thus served as a valuable model for studying developmentally-regulated autophagic cell death (Baehrecke, 2005). Interestingly, death of these tissues displays characteristics of both autophagy, such as abundant cytoplasmic vacuolization, as well as apoptosis, including the upregulation of proapoptotic genes, caspase activation and DNA cleavage (Lee et al., 2002; Martin and Baehrecke, 2004). Elimination of larval gut and salivary glands can be partially suppressed or delayed by mutations in components of either the apoptotic or autophagic machinery (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Juhasz et al., 2007; Muro et al., 2006). Disruption of both autophagy and apoptosis results in a more complete suppression (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007), indicating that these processes act cooperatively, and that one process may be upregulated to compensate for the lack of the other. Pupal development is delayed by approximately four hours in Atg7 mutant animals, consistent with a reduction in the efficiency of cell elimination when autophagy is defective (Juhasz et al., 2007). The ultimate viability of these mutants, however, indicates that other death mechanisms are sufficient to compensate for this defect. A similar combination of apoptotic and autophagic morphologies has been described in the death of nurse and follicle cells during oogenesis in a number of insects, including silkmoths, medflies, and other Drosophila species (Mpakou et al., 2006; Nezis et al., 2006; Velentzas et al., 2007), although the requirement for these processes in cell death has yet to be determined experimentally in these cases.

Under what conditions and in what cell types is autophagy likely to be used as a means of cell death? Although phagocytes normally play an important role in eliminating apoptotic corpses, few phagocytes are observed in dying salivary glands. The extremely large size of polyploid larval cells, their sequestration into inaccessible areas of the body cavity, and the sheer number of cells dying during metamorphosis may preclude their efficient engulfment by phagocytes, necessitating their self-clearance by autophagy. However, although the function of autophagy in the death of these cells would appear to be direct, it is important to consider other mechanisms by which autophagy may contribute to cell elimination. In an in vitro model of mouse embryonic cavitation using embryoid bodies derived from ES cells, it was found that disruption of autophagy prevented the clearance of the inner core of ectodermal cells, which normally die by an apoptotic form of programmed cell death (Qu et al., 2007). In this case, however, autophagy was required not as an effector of death nor to degrade dying cells, but rather as an energy source to facilitate signaling from the dying cells to macrophages (Qu et al., 2007). The absence of autophagy resulted in decreased engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages, leading to accumulation of apoptotic corpses within the embryoid bodies. These results suggest that caution is warranted when interpreting effects of autophagy on apoptosis. For example, the observed increase in apoptotic corpses in bec-1 mutant embryos in C. elegans (Takacs-Vellai et al., 2005) may reflect either an increased rate of apoptosis or a decrease in the clearance of dead cells.

So far, there is only limited evidence that autophagy functions as a death mechanism in cells with an intact apoptotic pathway, apart from the studies described above in Drosophila. In mammalian cells, most reports of the involvement of autophagy in the death execution process are in cells that are defective in the apoptotic pathways (Levine and Yuan, 2005; Maiuri et al., 2007b). Furthermore, defects in autophagy, as in bec-1/Atg6 or beclin 1 mouse knockouts, cause an increase, and not a decrease in cell death, supporting a pro-survival role for autophagy during development.

Recent studies of EGL-1 in C. elegans, provide interesting insights in regard to the connection between autophagy and apoptosis (Maiuri et al., 2007a). EGL-1 encodes a novel protein that contains a Bcl-2 homology-3 (BH3) domain. In C. elegans, EGL-1 functions as a positive regulator of apoptosis by interacting directly with the antiapoptotic CED-9 to induce the release of CED-4 from CED-4/CED-9 complexes, resulting in the activation of the caspase CED-3 (Conradt and Horvitz, 1998; Conradt and Horvitz, 1999; del Peso et al., 1998; Trent et al., 1983). While a deletion of egl-1 compromises starvation-induced autophagy, a gain-of-function mutation of egl-1 induces autophagy (Maiuri et al., 2007a). The interaction between mammalian Bcl-2/Bcl-xL and Beclin 1 involves a BH3 domain within Beclin 1, and this interaction is competitively blocked by the overexpression of BH3-only pro-apoptotic proteins or by pharmacological BH3 mimetics (Maiuri et al 2007b). Thus, EGL-1 might not only positively regulate programmed cell death, but might also positively regulate autophagy by interacting with CED-9 to induce BEC-1 release from CED-9/BEC-1 complexes. It is unclear whether the increase in autophagy in egl-1 mutants contributes directly to cell death. Future studies in C. elegans should clarify the molecular cross-talk between the autophagic and apoptotic machinery during development.

In addition to these connections between autophagy and apoptosis, recent studies suggest that autophagy may also play a role in necrotic cell death. Gain of function mutations in C. elegans ion channel genes (mec-4 or deg-1), the acetylcholine receptor channel subunit gene (deg-3), and the Gs protein α-subunit gene (gsa-1), cause a necrotic-like cell degeneration in neurons (Berger et al., 1998; Chalfie and Wolinsky, 1990; Driscoll and Chalfie, 1991; Korswagen et al., 1997; Treinin and Chalfie, 1995). Studies of dying neurons in animals carrying the gain of function mec-4(d) allele, display extensive degradation of cellular contents during the process of necrosis (Hall et al., 1997). This ultrastructural feature is reminiscent of autophagy and does not require the caspase CED-3, which mediates programmed cell-death, nor CSP-1, CSP-2 or CSP-3 (CED-3 related proteases)(Chung et al., 2000), indicating that a distinct and non-apoptotic mechanism may function in neurodegeneration (Syntichaki et al., 2002). The knockdown of three autophagy transcripts (unc-51/ATG1, bec-1/ATG6, and lgg-1/ATG8) by RNAi suppresses the degeneration of neurons with hyperactive toxic ion channels (Toth et al., 2007), suggesting a role for autophagy in cellular necrosis. Recently, Samara et al. have also shown that excessive autophagosome formation is induced early during necrotic cell death and that the autophagy pathway synergizes with lysosomal proteolytic mechanisms to facilitate necrotic cell death in C. elegans neurons (Samara et al., 2008). Together these results suggest that the boundaries between apoptotic, autophagic and necrotic forms of cell death are not sharply defined, and aspects of each mechanism can be used together to achieve a cell death process that is appropriate for a given developmental context.

Autophagy and disease

The recent surge in interest and activity in the field of autophagy research is driven in part by the impact of this process on several aspects of human health and disease, and by the potential opportunity to develop novel therapies involving the manipulation of autophagy (Box 2). In two areas in particular, tumorigenesis and neurodegeneration, autophagy plays an important role, and developmental studies in model organisms are leading to new insights into disease mechanism and potential therapeutic strategies.

Box 2. Autophagy and human health.

As a fundamental cellular process important for energy homeostasis and renewal, it is perhaps not surprising that defects in autophagy are being associated with an increasing assortment of human diseases. As in the case for tumorigenesis and neurodegeneration described in the text, autophagy can potentially play both beneficial and detrimental roles in these other contexts as well. For example, autophagy has been shown to impact immune system function at several levels, acting to promote the degradation of a variety of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses and intracellular parasites (Andrade et al., 2006; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Talloczy et al., 2006). In contrast, some viruses are able to subvert the autophagic machinery to their advantage, utilizing autophagosomal membranes to facilitate viral replication and release (Jackson et al., 2005). Autophagy also plays a central role in the processing, and MHC class II-mediated presentation of intracellular antigens (Munz, 2006). Recently, Atg16L has been identified as a susceptibility gene for Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory disorder associated with a maladaptive immune response to intestinal flora (Rioux et al., 2007). The potential roles of autophagy in this, and other, immune-related illnesses in vivo should soon become more clear through studies in Atg mutant model organisms.

Accumulating evidence suggests that autophagy may play an especially prominent role in the heart, consistent with the high metabolic demand placed on cardiomyocytes, the contractile cells of cardiac tissue. As observed in the nervous system, basal levels of autophagy are critical for normal cell function in the mouse heart (Nakai et al., 2007). In addition, autophagy is markedly upregulated in cardiac cells in response to a number of stresses, including ischemia, hypoxia, and pressure overload. The role and ultimate outcome of this increase in autophagy is as yet unclear. For example, pathological effects of pressure overload were reported to be either less or more severe in mice mutant for different autophagy related genes (Nakai et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2007). In mouse models of ischemia/reperfusion, autophagic activation plays an adaptive role at the early stage of insult but have harmful effects in the recovery phase (Matsui et al., 2007).

One promising area in which the effects of autophagy may be more purely beneficial is in promoting longevity. Treatments that induce autophagy such as caloric restriction and reduced insulin or TOR signaling are known to increase lifespan across the animal kingdom, and in C. elegansthese effects depend on autophagy (Meléndez et al., 2003). Direct manipulation of the autophagic machinery through increased expression of the Atg8agene has also been shown to extend life in Drosophila(Simonsen et al., 2008).

Together, these types of studies can point toward specific dietary programs and pharmaceutical interventions that may provide effective therapy for a number of medical conditions. Pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy such as 3-methyladenine (3-MA) and the AMP-activated protein kinase activator, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-s-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR), and autophagy inducers such as rapamycin, an FDA-approved immunosuppressant, serve as proof-of-principle that drugs targeting autophagy can be effectively developed. Although these compounds are not selective for autophagy, recent small-molecule screens have begun to identify additional autophagy modulators (Sarkar et al., 2007), and an important future goal will be to develop drugs that specifically target autophagy.

Although correlations between malignancy and defects in autophagy have long been noted, the first indication of a mechanistic connection between autophagy and cancer came from studies of beclin 1, which is monoallelically deleted in a high percentage of human breast and prostrate cancer (Aita et al., 1999; Liang et al., 1999). The heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 gene in mice was found to increase the rate of spontaneous and virally-induced tumor formation, confirming the role of beclin 1 as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor (Qu et al., 2003; Yue et al., 2003). Other components of the Beclin 1/Vps34 complex, including UVRAG and Bif-1, also have tumor suppressive properties (Liang et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2007). Recent studies by White and colleagues have demonstrated that a loss of autophagy in immortalized mouse epithelial cells leads to a marked increase in DNA damage, genomic instability and necrosis, all of which potentially contribute to tumorigenesis (Degenhardt et al., 2006; Mathew et al., 2007). In contrast to this tumor suppressive function, autophagy might promote tumorigenesis by supporting the growth and survival of solid tumors at early stages of development, prior to vascularization. Thus autophagy appears to play both positive and negative roles at different stages of cancer development. Studies of the normal functions of autophagy during vasculogenesis in developing embryos may help to clarify these issues. Indeed, observations of increased inflammatory responses in atg5 mutant mouse embryos (Qu et al., 2007) suggest additional mechanisms by which autophagy may contribute to tumorigenesis.

An essential role for autophagy has also been found in the maintenance of axonal homeostasis and prevention of neurodegeneration (Rubinsztein, 2006). As in the case of cancer, autophagy appears to play primarily a protective role against neuropathy, likely stemming from the function of basal autophagy in degrading damaged organelles and aggregate-prone proteins. This neuroprotective role is exemplified by the neurodegeneration phenotypes observed in fly and mouse autophagy mutants, and by the suppression of polyglutamine-induced toxicity by autophagy in fly and worm models of Huntington’s and other neurodegenerative diseases (Hara et al., 2006; Jia et al., 2007; Juhasz et al., 2007; Komatsu et al., 2006; Sarkar et al., 2007). However, in some cases autophagy appears to play dual harmful and beneficial roles in neuronal health. For example, autophagy contributes to the production of amyloid beta peptide through degradation of amyloid beta precursor protein (APP)-containing organelles. Normally this toxic peptide is degraded following the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes; however, in Alzheimer disease, the fusion process of autophagosomes with lysosomes is defective, leading to the massive accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and to increased amyloid beta levels in the degenerating neurons (Nixon, 2007). A similar accumulation of autophagic vacuoles has been described in an increasing number of neurodegenerative conditions, but additional investigation is necessary to determine whether this represents increased induction of autophagy or defects in autophagosome turnover.

Conclusions

In the past few years, there has been a deluge of publications identifying many of the components of the protein machinery involved in autophagic function in yeast, and providing insights as to the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Although orthologs to many of these components exist in metazoans, in some cases formal proof of their involvement in autophagy is still lacking. Another area where our understanding is still limited is that of the regulatory pathways that control autophagy, and the level of cross-talk that likely exists between these pathways. Genetic model organisms may be able to shed light on this issue. Based on our current understanding of the physiological functions of autophagy, both basal levels and stress-induced levels of autophagy can promote mammalian health. Autophagy maintains energy homeostasis and provides nutrients under conditions of stress and nutrient deprivation. In addition, autophagy rids the cell of intracellular proteins and damaged organelles that may cause cellular degeneration, genomic instability, tumorigenesis and aging.

As our appreciation of the roles of autophagy in cancer, neurodegeneration and other diseases grows, it will become increasingly important to understand the normal range of autophagic functions and control mechanisms in the healthy state. Increased insight into the developmental roles of autophagy is likely to point toward ways in which this process can be exploited for therapeutic purposes. A challenge for the future will be to identify the signaling mechanisms and regulatory steps that can be targeted for intervention, and to determine the circumstances under which autophagy plays a net beneficial vs. detrimental role. Developmental studies in nematodes, flies and mice have already begun to shed light onto the variety of uses to which autophagy has been put by evolution, and how this fascinating process influences a wide spectrum of developmental events.

Acknowledgments

The work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by NIH grants GM62509 (T.P.N.) and 3R01AG024882-04S1 (A.M.), and by the PSC CUNY Research Award Program (A.M.). We thank Hannes Bulow for comments and helpful suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VV, Pincus DL, Yu W, Cayanis E, Kalachikov S, Gilliam TC, Levine B. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics. 1999;59:59–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, Bui T, Christophorou MA, Evan GI, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Thompson CB. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:326–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI28833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade RM, Wessendarp M, Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Subauste CS. CD40 induces macrophage anti-Toxoplasma gondii activity by triggering autophagy-dependent fusion of pathogen-containing vacuoles and lysosomes. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2366–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI28796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehrecke EH. Autophagy: dual roles in life and death? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:505–10. doi: 10.1038/nrm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri M, Bonafe M, Franceschi C, Paolisso G. Insulin/IGF-I-signaling pathway: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of longevity from yeast to humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E1064–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00296.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini E, Cavallini G, Donati A, Gori Z. The role of macroautophagy in the ageing process, anti-ageing intervention and age-associated diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AJ, Hart AC, Kaplan JM. G alphas-induced neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2871–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02871.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S, McDonald KL, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DL, Baehrecke EH. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;131:1137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommaart EF, Luiken JJ, Blommaart PJ, van Woerkom GM, Meijer AJ. Phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 is inhibitory for autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2320–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botti J, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Pilatte Y, Codogno P. Autophagy signaling and the cogwheels of cancer. Autophagy. 2006;2:67–73. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Casares N, Perfettini JL, Dessen P, Larochette N, Metivier D, Meley D, Souquere S, Yoshimori T, et al. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1025–40. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1025-1040.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JS, Edgar BA. Environmental control of the cell cycle in Drosophila: nutrition activates mitotic and endoreplicative cells by distinct mechanisms. Development. 1998;125:2149–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JS, Lockwood WK, Li L, Cohen SM, Edgar BA. Drosophila’s insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev Cell. 2002;2:239–49. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassada RC, Russell RL. The dauerlarva, a post-embryonic developmental variant of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1975;46:326–42. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Wolinsky E. The identification and suppression of inherited neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1990;345:410–6. doi: 10.1038/345410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan EY, Kir S, Tooze SA. siRNA screening of the kinome identifies ULK1 as a multidomain modulator of autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25464–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Gumienny TL, Hengartner MO, Driscoll M. A common set of engulfment genes mediates removal of both apoptotic and necrotic cell corpses in C. elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:931–7. doi: 10.1038/35046585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans protein EGL-1 is required for programmed cell death and interacts with the Bcl-2-like protein CED-9. Cell. 1998;93:519–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B, Horvitz HR. The TRA-1A sex determination protein of C. elegans regulates sexually dimorphic cell deaths by repressing the egl-1 cell death activator gene. Cell. 1999;98:317–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C. The lysosome turns fifty. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:847–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb0905-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen G, Mukherjee C, Shi Y, Gelinas C, Fan Y, et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Peso L, Gonzalez VM, Nunez G. Caenorhabditis elegans EGL-1 disrupts the interaction of CED-9 with CED-4 and promotes CED-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33495–500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding WX, Ni HM, Gao W, Yoshimori T, Stolz DB, Ron D, Yin XM. Linking of autophagy to ubiquitin-proteasome system is important for the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell viability. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:513–24. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll M, Chalfie M. The mec-4 gene is a member of a family of Caenorhabditis elegans genes that can mutate to induce neuronal degeneration. Nature. 1991;349:588–93. doi: 10.1038/349588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fader CM, Colombo MI. Multivesicular bodies and autophagy in erythrocyte maturation. Autophagy. 2006;2:122–5. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimia GM, Stoykova A, Romagnoli A, Giunta L, Di Bartolomeo S, Nardacci R, Corazzari M, Fuoco C, Ucar A, Schwartz P, et al. Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature. 2007;447:1121–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-McClure ML, Hohsfield LA, Fonte G, Bealor MT, Link CD. Decreased insulin-receptor signaling promotes the autophagic degradation of beta-amyloid peptide in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2007;3:569–80. doi: 10.4161/auto.4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi T, Matsuura A, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Analyses of APG13 gene involved in autophagy in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1997;192:207–13. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DH, Gu G, Garcia-Anoveros J, Gong L, Chalfie M, Driscoll M. Neuropathology of degenerative cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1033–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-01033.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Chandra A, Mitic LL, Onken B, Driscoll M, Kenyon C. A Role for Autophagy in the Extension of Lifespan by Dietary Restriction in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Taubert S, Crawford D, Libina N, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. Lifespan extension by conditions that inhibit translation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding TM, Morano KA, Scott SV, Klionsky DJ. Isolation and characterization of yeast mutants in the cytoplasm to vacuole protein targeting pathway. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:591–602. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hars ES, Qi H, Ryazanov AG, Jin S, Cai L, Hu C, Liu LF. Autophagy regulates ageing in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2007;3:93–5. doi: 10.4161/auto.3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock EM, Culotti JG, Thomson JN, Perkins LA. Axonal guidance mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans identified by filling sensory neurons with fluorescein dyes. Dev Biol. 1985;111:158–70. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemelaar J, Lelyveld VS, Kessler BM, Ploegh HL. A single protease, Apg4B, is specific for the autophagy-related ubiquitin-like proteins GATE-16, MAP1-LC3, GABARAP, and Apg8L. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51841–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO, Horvitz HR. C. elegans cell survival gene ced-9 encodes a functional homolog of the mammalian proto-oncogene bcl-2. Cell. 1994;76:665–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges KE, Sirry B, Gingeras AC, Sarbassov D, Sonenberg N, Sabatini D, Peterson AS. FRAP/mTOR is required for proliferation and patterning during embryonic development in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13796–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241184198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N, Hara Y, Mizushima N. Generation of cell lines with tetracycline-regulated autophagy and a role for autophagy in controlling cell size. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2623–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer-Hansen M, Jaattela M. AMP-activated protein kinase: a universal regulator of autophagy? Autophagy. 2007;3:381–3. doi: 10.4161/auto.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, Satomi Y, Shimonishi Y, Ishihara N, Mizushima N, Tanida I, Kominami E, Ohsumi M, et al. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature. 2000;408:488–92. doi: 10.1038/35044114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata J, Ezaki J, Komatsu M, Yokota S, Ueno T, Tanida I, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Kominami E. Excess peroxisomes are degraded by autophagic machinery in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4035–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WT, Giddings TH, Jr, Taylor MP, Mulinyawe S, Rabinovitch M, Kopito RR, Kirkegaard K. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia K, Chen D, Riddle DL. The TOR pathway interacts with the insulin signaling pathway to regulate C. elegans larval development, metabolism and life span. Development. 2004;131:3897–906. doi: 10.1242/dev.01255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia K, Hart AC, Levine B. Autophagy genes protect against disease caused by polyglutamine expansion proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans. Autophagy. 2007;3:21–5. doi: 10.4161/auto.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia K, Levine B. Autophagy is required for dietary restriction-mediated life span extension in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2007;3:597–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz G, Csikos G, Sinka R, Erdelyi M, Sass M. The Drosophila homolog of Aut1 is essential for autophagy and development. FEBS Lett. 2003;543:154–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz G, Erdi B, Sass M, Neufeld TP. Atg7-dependent autophagy promotes neuronal health, stress tolerance, and longevity but is dispensable for metamorphosis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3061–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1600707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhász G, Hill JH, Yang Y, Sass M, Baehrecke EH, Backer JM, Neufeld TP. The class III PI(3)K Vps34 promotes autophagy and endocytosis but not TOR signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712051. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. Embo J. 2000;19:5720–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y, Funakoshi T, Shintani T, Nagano K, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1507–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kametaka S, Matsuura A, Wada Y, Ohsumi Y. Structural and functional analyses of APG5, a gene involved in autophagy in yeast. Gene. 1996;178:139–43. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kametaka S, Okano T, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. Apg14p and Apg6/Vps30p form a protein complex essential for autophagy in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22284–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C, You YJ, Avery L. Dual roles of autophagy in the survival of Caenorhabditis elegans during starvation. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2161–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.1573107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P, Zid BM, Harper T, Koslover D, Sapin V, Benzer S. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2004;14:885–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y. Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:519–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Sun H. Functional genomic approach to identify novel genes involved in the regulation of oxidative stress resistance and animal lifespan. Aging Cell. 2007;6:489–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Baba M, Ishihara N, Miyazawa K, Ohsumi M, Yoshimori T, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Formation process of autophagosome is traced with Apg8/Aut7p in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:435–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Ichimura Y, Okada H, Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi M, Takao T, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. The reversible modification regulates the membrane-binding state of Apg8/Aut7 essential for autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:263–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissova I, Salin B, Schaeffer J, Bhatia S, Manon S, Camougrand N. Selective and non-selective autophagic degradation of mitochondria in yeast. Autophagy. 2007;3:329–36. doi: 10.4161/auto.4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:931–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS, Baba M, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Ballabio A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151–75. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, Murata S, Iwata J, Tanida I, Ueno T, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, Iwata J, Murata S, Tanida I, Ezaki J, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]