Abstract

Objective

To determine if loss of protein kinase Cγ (PKCγ) results in increased structural damage to the retina by hyperbaric oxygen (HBO), a treatment used for several ocular disorders.

Methods

Six-week-old mice were exposed in vivo to 100% HBO 3 times a week for 8 weeks. Eyes were dissected, fixed, embedded in Epon, sectioned, stained with toluidine blue O, and examined by light microscopy.

Results

The thicknesses of the inner nuclear and ganglion cell layers were increased. Destruction of the outer plexiform layer was observed in the retinas of the PKCγ-knockout mice relative to control mice. Exposure to HBO caused significant degradation of the retina in knockout mice compared with control mice. Damage to the outer segments of the photoreceptor layer and ganglion cell layer was apparent in central retinas of HBO-treated knockout mice.

Conclusions

Protein kinase Cγ–knockout mice had increased retinal sensitivity to HBO. Results demonstrate that PKCγ protects retinas from HBO damage.

Clinical Relevance

Care should be taken in treating patients with HBO, particularly if they have a genetic disease, such as spinocerebellar ataxia type 14, a condition in which the PKCγ is mutated and nonfunctional.

Gap junctions have been called both “good Samaritans” and “executioners,”1 terms that refer to their ability to pass both necessary metabolites and apoptotic signals from cell to cell. It has been suggested that this spread of cell death takes place through open gap junctions, a process referred to as the bystander effect.1 The passage of apoptotic signals through gap junctions has been linked to oxidative cell death in retinal ischemia.2,3 Retinal gap junction proteins, such as connexin 43 (Cx43) and connexin 50 (Cx50), play important roles in retinal function, and defects in the control of these gap junction proteins may cause retinal cell death.4-7 In retinal and lens cells in culture, the gap junction proteins Cx43 and Cx50 are inhibited after phosphorylation by protein kinase Cγ (PKCγ), a process that is controlled by the cell oxidative state.8-10

Protein kinase Cγ belongs to a class of serine/threonine protein kinases that consist of at least 11 isoforms.11-18 Previous studies of PKCγ-knockout mice have shown reduced pain sensitivity and reduced protection against brain ischemia.19,20 However, no study has previously shown the effect of loss of PKCγ on these knockout animals' retinas, a tissue with known sensitivity to ischemia.

Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are heterogenous, autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorders that are clinically characterized by various symptoms, such as progressive ataxia of gait and limbs, cerebral dysarthria, and abnormal eye movement.21 Currently, 28 genetic loci have been linked to the clinical phenotype of SCA, and 14 causative genes have been identified.21 Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (SCA14) is caused by mutations in the PKCγ gene,22 a classic PKC isoform expressed primarily in the central nervous system, peripheral nerves, retina, and lens. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 is a very slowly progressive ataxia that mostly affects gait and limb coordination with age at onset as early as 3 years.22,23 Protein kinase Cγ consists of C1 and C2 regulatory domains and C3 and C4 catalytic domains. The C1 domain contains 2 tandem-repeat, cysteine-rich regions, C1Aand C1B. In families with SCA14, more than 20 missense coding mutations have been identified in PKCγ. Although the SCA14 mutations occur throughout the PKCγ gene from the regulatory to catalytic domains and also include a 6-pair inframe deletion (ΔK100-H101), most mutations occur in the C1B regulatory domain.22-24

Humans with SCA14 have point or truncation mutations in PKCγ, resulting in a nonfunctional enzyme.25 We have previously demonstrated that lens epithelial cells with PKCγ SCA14 mutants (H101Y, S119P, or G128D) lack PKCγ enzyme activity even when endogenous PKCγ is present.26 Effects are observed on gap junction proteins Cx43 and Cx50, which are both found in the retina.27,28 Protein kinase Cγ C1B mutants do not phosphorylate Cx43 or Cx50; they cause increased Cx43 and Cx50 plaques; and disassembly does not occur after hydrogen peroxide–stimulated activation of PKCγ.26 This dominant negative effect on endogenous PKCγ has been linked to failure of control of gap junctions and causes cells to be more susceptible to hydrogen peroxide–induced, caspase 3–dependent cell apoptosis.26

Connexin 43 is found in retinal glial cells, myelinated fiber regions of neural retinas, astrocytes, and fibrae circulares musculi ciliaris.29,30 Connexin 50, another PKCγ target, is expressed in retinal fibrae circulares musculi ciliaris, astrocytes, and filamentous processes sheathing the photoreceptors.5-7,31,32 Connexin 50 also couples between A type horizontal cells.27 Protein kinase C's are found in the bow region and cortex of the lens and in the cornea and retina.33-37

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) also causes oxidative stress in the live mouse model and is thought to deplete glutathione cells.38 It induces several physiological effects, such as increased blood pressure and hyperoxia. The HBO model is a noninvasive technique that is widely used for treatments of humans with stroke.39,40 It has also been used to ameliorate damage in the blood-retinal barrier in diabetic retinopathy.41 There are also adverse effects associated with HBO treatments, such as damage to ears, increased oxygen toxicity, and pulmonary barotraumas.40 Our goal was to determine if loss of PKCγ in knockout mice increased sensitivity of the retina to HBO stress, resulting in retinal cell damage.

Methods

Animals

Six-week-old control mice and 6-week-old PKCγ-knockout mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Massachusetts). Control and knockout mice were treated with elevated pressure of 100% oxygen, 3 times per week for 8 weeks. The course of treatment was as follows: treatment 1, 2.5 atm for 1 hour; treatments 2 and 3, 2.5 atm for 2.5 hours; treatments 4 through 9, 2.5 atm for 3 hours; and treatments 10 through 24, 3.0 atm for 3 hours. The mice were aged 14 weeks by the end of treatment. The mice tolerated the HBO treatments well. Animals were euthanized according to approved protocols. All experiments conformed to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were performed under an institutionally approved animal protocol.

Western Blot

Retinal tissues were collected within 5 minutes of euthanization in ×2 sample buffer (100mM Tris hydrochloric acid, pH 6.8, 200mM dithiothreitol, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.2% bromphenol blue, 20% glycerol; 50 μL per retina). Proteins were separated by 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (40-μg retinal protein/lane) and underwent Western blots using monoclonal mouse anti-PKCγ antibodies (1:1000) from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, Missouri), mouse anti-Cx50 antisera (1:500) from Zymed (San Francisco, California), and/or mouse anti–β-actin antibody from Sigma-Aldrich. Immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence.

Light Microscopy

Eyes were dissected in 6- to 14-week-old mice, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.1M cacodylate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania) then postfixed with osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences). This was followed by dehydration with 70% alcohol for 12 hours, then with 100% alcohol overnight and with 100% acetone for 12 hours then embedded in Epon LX112 (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Sectioning was done using a Reichter-Jung Ultracut E Ultramicrotome (Cambridge Instruments Inc, Buffalo, New York) at room temperature. Sections were taken perpendicular to the optic nerve so that all of the layers of the retina could be observed. Eyes were sectioned until the optic nerve was observed, so that the depth was consistent in all of the sections. Thick sections (2-50 μm) were obtained using a diamond knife, then stained with 1% (weight to volume) toluidine blue O (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and viewed using a Nikon Eclipse E600 light microscope (Nikon Inc, Melville, New York) (×4-100 original magnification). Exact locations were confirmed by low-magnification photographs (×4-100 original magnification) and analyzed using analySIS software (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Munster, Germany). Statistical analyses were done using Origin 5.0 (Microcal Software Inc, Northampton, Massachusetts).

Results

Pkcγ in Retinas of Knockout Mice

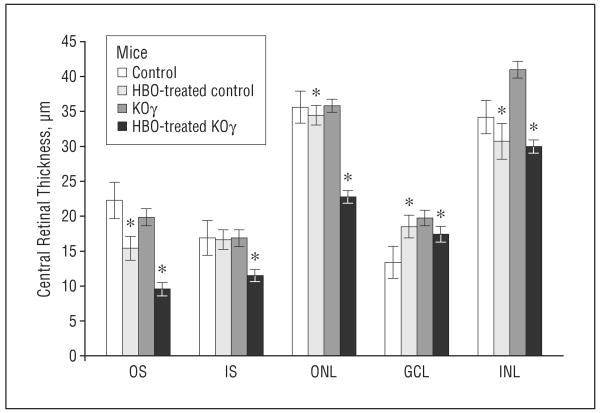

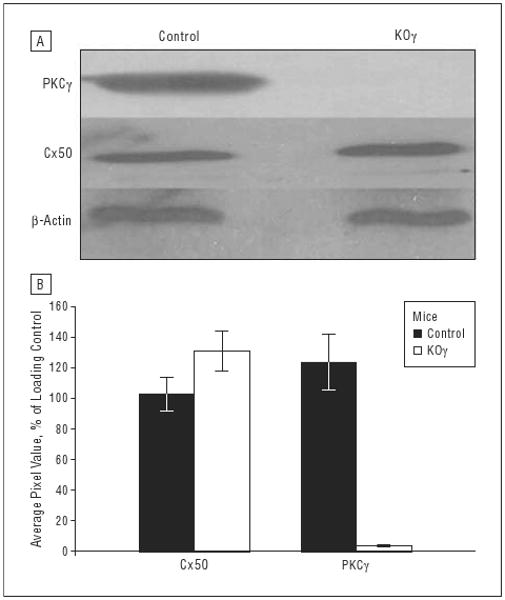

Western blot analysis was performed to confirm a lack of PKCγ protein in the retinas of PKCγ-knockout mice. Figure 1 illustrates that 6-week-old knockout mice have no detectable PKCγ in the retina. Western blots did not demonstrate any change in Cx50 protein, used as a control, in the retinas of knockout mice compared with those in control mice, indicating that normal levels of possible PKCγ targets remain intact in the knockout mice (Figure 1). As this is a well-studied knockout model, we did not examine additional protein levels. Extensive analysis in the brain has already established validity of this model.42,43

Figure 1.

Western blots of whole retinal tissue. Whole retina from 6-week-old control or protein kinase Cγ– (PKCγ-) knockout (KOγ) mice were loaded in sample buffer at 40-μg protein per lane. A, Immunoblots using mouse anti-PKCγ antisera at 1:1000, mouse anti–connexin 50 (Cx50) at 1:500, and mouse anti–β-actin at 1:20 000. β-Actin is used as an internal loading control. B, The average pixel values of Cx50 and PKCγ in control and KOγ mice. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

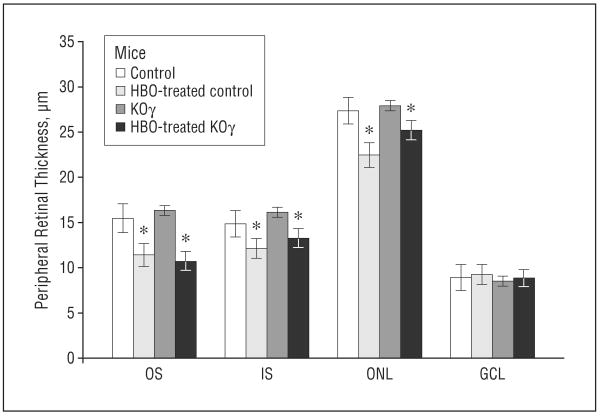

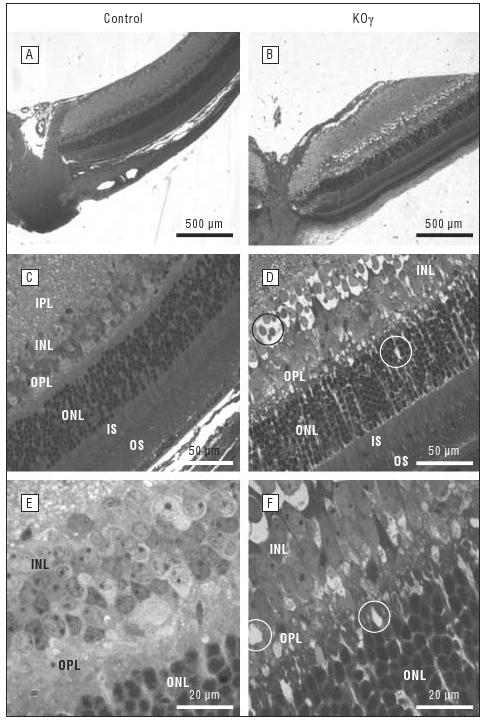

Structural Changes in Retinas of Knockout Mice at 6 Weeks of Age

All eyes were sectioned perpendicular to the optic nerve, so that we were able to view all 7 retinal layers. To keep all eyes at equal sectioning depth, we sectioned them until the optic nerve was visible (Figure 2). The widths of all the layers were determined to be 250 μm (central) and 1100 μm (peripheral) from the optic nerve. Average thicknesses for control and knockout retinas were measured using analySIS software (Figure 3 and Figure 4). It is apparent that differences in thickness and structural integrity are present when comparing control and knockout mice (even without HBO treatment), especially in the central retina 250 μm from the optic nerve (Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Structural analyses of retinas in 6-week-old control and protein kinase Cγ–knockout (KOγ) mice by light microscopy. A and B, The whole retina and optic nerve at ×4 original magnification. C and D, All the layers of the retina at ×40 original magnification. E and F, The inner nuclear layer (INL) and outer plexiform layer (OPL) at ×100 original magnification. All sections are approximately 250 μm from the optic nerve. IPL indicates inner plexiform layer; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segments. Vacuoles are circled.

Figure 3.

Thickness of central retinal layers in control and protein kinase Cγ–knockout (KOγ) mice. In knockout mice, the inner nuclear layer (INL) includes the outer plexiform layer, as the border is undefined. GCL indicates ganglion cell layer; HBO, hyperbaric oxygen; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segments. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. *Statistically significant, P≤.05.

Figure 4.

Thickness of peripheral retinal layers in control and protein kinase Cγ–knockout (KOγ) mice. GCL indicates ganglion cell layer; HBO, hyperbaric oxygen; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segments. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. *Statistically significant, P≤.05.

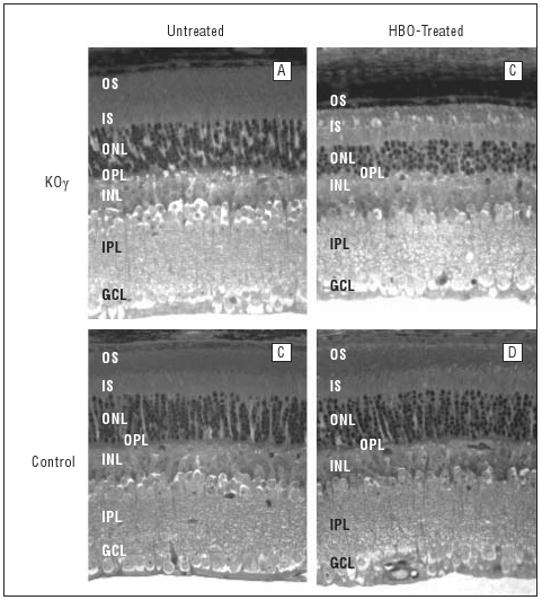

Figure 5.

Structure of mouse retinas (aged 14 weeks) before and after hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) treatment. Sections of fixed retina, about 250 μm away from the optic nerve, are shown. GCL indicates ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; IS, inner segments; KOγ, protein kinase Cγ knockout; ONL, outer nuclear layer, OPL, outer plexiform layer; OS, outer segments.

We observed that the average thicknesses of the ganglion cell layer in the knockout mice were consistently greater by about 25%. The inner nuclear layer in some retinas (Figures 2 and 3) were about 30% thicker, which was due to the formation of vacuoles (empty space) between the cells (shown circled, Figures 2 and 5). These increases in thickness, when values were averaged among many retinas, were not significant, though vacuoles appeared in all inner nuclear layers in the retinas of knockout mice. The total number of nuclei in the outer nuclear layer was reduced by about 20% in the central retinas of knockout vs control mice (Figure 5 and the Table). The vacuoles that were observed in PKCγ-knockout retinas (Figure 2, Figure 5, and Figure 6) were responsible for the increase in thickness and reduction of total nuclei in the inner nuclear layer, outer nuclear layer, and ganglion cell layer (Figure 4 and the Table).

Table. Nuclei in the INL, ONL, and GCL of Control and PKCγ-Knockout Mice.

| Nuclei/1000 μm2, Mean (SEM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | INL | ONL | GCL |

| Central Retina, 250 μm From the Optic Nerve | |||

| Control | 20 (0.58) | 59 (2.1) | 13 (1.5) |

| HBO-treated control | 21 (0.75) | 50.5 (3.6) | 9 (0.75) |

| PKCγ knockout | 15 (1.2) | 45.2 (5.1) | 7.5 (0.5) |

| HBO-treated PKCγ knockout | 18 (1.5) | 32.2 (6.2) | 6.5 (0.55) |

| Peripheral Retina, 1100 μm From the Optic Nerve | |||

| Control | 19 (1.2) | 47.5 (1.8) | 11 (1.1) |

| HBO-treated control | 19.5 (1.4) | 47.5 (3.1) | 10 (1) |

| PKCγ knockout | 15 (0.75) | 42.2 (2.8) | 8 (0.5) |

| HBO-treated PKCγ knockout | 16 (1) | 43.8 (3.6) | 7 (0.75) |

Abbreviations: GCL, ganglion cell layer; HBO, hyperbaric oxygen; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; PKCγ, protein kinase Cγ; SEM, standard error of the mean.

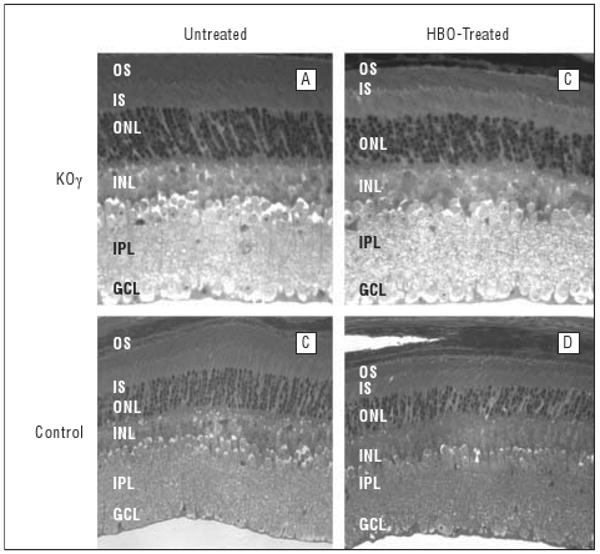

Figure 6.

Structure of mouse retina (aged 14 weeks) before and after hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) treatment. Sections of fixed retina, about 1100 μm away from the optic nerve, are shown. GCL indicates ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; IS, inner segments; KOγ, protein kinase Cγ knockout; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segments.

The greatest damage was observed in the outer plexiform layer. This layer was completely undefined; therefore, when measuring thicknesses, we combined the outer plexiform layer with the inner nuclear layer. The outer plexiform layer had extreme vacuoles and lacked any kind of organization or structure (Figures 2 and 5). The outer plexiform layer of control retinas appeared normal (Figure 2).

The outer nuclear layer of the knockout retinas had 9 to 10 layers of nuclei vs 10 to 11 layers of nuclei in the control mice. This was not reflected in the thickness measurements, probably because of increased space (due to formation of vacuoles, resulting in overall reduction of nuclei per unit area) (Table). The photoreceptor layers and the inner plexiform layers were comparable in the control and knockout mouse retinas.

Sensitivity to Hbo Damage in Knockout Mice

After HBO treatments, the thickness and structural differences between control and knockout retinas were more apparent. In Figure 5 we show the results of treating 6-week-old mice with HBO (100%), 3 times a week for 8 weeks (see the “Methods” section). Light microscopy in all retinal layers in the central area of the retina near the optic nerve demonstrated the most prevalent damage (Figures 3 and 5). As shown, the reduction of all layers was extensive in the PKCγ-knockout mice, whereas damage was much less severe in control mice. In particular, a severe loss of outer segments in the photoreceptor layers was observed. The average thickness was reduced by more than 50% (Figures 3 and 5) in knockout retinas after HBO treatment vs a 25% decrease in the control retina. In addition to reduction of thickness, the integrity of the outer segment seemed completely collapsed (Figure 5). Vacuoles were observed between the inner and outer segments, and outer segment fibers had no apparent direction in knockout retinas compared with control fibers, which were organized in a very tight manner. Figure 5 demonstrates the extreme increase of structural damage to the outer segments of knockout retina compared with control retina after HBO treatment.

The outer nuclear layer, which contains the nuclei of photoreceptor cells, decreased significantly in thickness in knockout mice after HBO treatment. The thickness of the outer nuclear layer decreased by 45% in the HBO-treated knockout mice (Figure 3) compared with no decrease in control retinas. The number of layers of nuclei also decreased in the HBO-treated knockout mice from 8-9 to 4-5 layers. This was not observed in control retinas.

Ganglion cell layers were also damaged in the knockout retinas even after HBO treatment. Figure 5 shows many vacuoles in the ganglion cell layer, resulting in an increase in thickness of this layer. The total number of nuclei decreased (Table), indicating that the increase in thickness was due to formation of vacuoles and not to the extra nuclei. The HBO-treated knockout ganglion cell layer had the same thickness, but the number of nuclei was reduced significantly. Ganglion cell layers from HBO-treated knockout mice had 11 valid nuclei, while the untreated knockout mice had 17 per 100 μm of ganglion cell layer.

Figure 6 demonstrates that the structural effects on peripheral retina were not as significant as on the central retina. The thickness of outer segments of photoreceptor layers was reduced to a lesser extent and there were not significant differences between the knockout and control mice in other layers. This fact indicates that the knockout mice are much more sensitive to HBO damage in the central retina than in the peripheral retina.

Comment

Results from this study clearly demonstrate that retinas from PKCγ-knockout mice are more sensitive to damage from HBO treatments. Previous findings suggest that PKCγ is required for protection of the brain from ischemic stress damage.19 The PKCγ-knockout model is more sensitive to pain and has changes in long-term potentiation, increased alcohol consumption, enhanced opioid response, and decreased memory.42,43 Protein kinase Cγ is involved in brain ischemic responses and it may serve a similar role in retinas in cell regulation and developmental signaling.

Protein kinase Cγ is an important enzyme in signal-transduction pathways. One of its functions is to regulate gap junction signaling.8-10,16 Thus, by knocking out PKCγ, the signal transduction pathway and gap junction control may be disrupted in the retina. Gap junctions, like those assembled from Cx50 or Cx43, though still present in the knockout mice (Figure 1), may be dependent on PKCγ for closure in response to oxidative stress (ie, the bystander effect). Gap junctions are observed throughout the retina and provide electrical coupling between retinal cells.28,44-47

Besides gap junctions, there are several other targets of PKCγ that are involved in neural protection and transmission of synaptic signals. Ionotropic glutamate receptors, which play a role in signal transduction in the brain and are involved in learning and memory formation, are regulated by phosphorylation. Protein kinase Cγ has been shown to phosphorylate the GluR4 ser-482 α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate–type glutamate receptor.48 Calmodulin-binding RC3 (neurogranin) is phosphorylated through the activation of the postsynaptic glutamate receptor by PKCγ.49 Protein kinase Cγ has also been shown to be associated with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor–associated signal transduction, which is specifically associated with diacylglycerol levels.50 The exact biochemical effects in PKCγ-knockout mice are yet to be identified. In this study, we explore its overall structural effect on the retina from the knockout-mouse model and determine that retinas show increased damage after HBO treatments. This could be partly due to uncontrolled gap junctions.

The bystander effect occurs when an adjacent cell delivers a cellular apoptotic signal, such as high Ca+2, to an adjacent cell through an open gap junction, causing spread of the death signal.51,52 The process is well documented in brain injury caused by ischemia, in which the expansion of the ischemic infarct results from transfer of apoptotic signal molecules through gap junctions of astrocytes and other cells.1-4 It is apparent that proper control of gap junctions is required for retinal cell survival and the identification of the gap junctions. Their control mechanisms provide a challenge for future work.

Protein kinase Cγ is a member of the classic PKC family and has both a C1, diacylglycerol-binding domain and a C2, calcium-binding domain.20 Unlike other classic PKCs, PKCγ can be activated directly by an oxidative signal without elevated calcium.8 The C1 domain of PKCγ is exposed and becomes oxidized upon exposure of cells to hydrogen peroxide.12 This causes PKCγ enzyme activation, phosphorylation of Cx43 and Cx50, and inhibition of these gap junctions.8 Protein kinase Cγ is found in the retinas of normal but not knockout mice (Figure 1). Thus, normal control of Cx43 and/or Cx50 gap junctions in response to stress would not occur. This would be reflected in enhanced damage to retinas in these mice.

A similar condition is observed in mutants of PKCγ, which mimic mutations found in humans with SCA14. When these mutations are overexpressed in neural mouse hippocampal (HT22) cells, gap junctions are no longer controlled, the mutation causes inactivation of the endogenous and normal PKC, and there is increased apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress.25 Because HBO is sometimes used to treat a number of conditions, it may be critical to know if PKCγ is normal in certain patients.

We have chosen HBO as a stress signal because it is noninvasive and unlike other treatments does not require anesthesia, which activates PKC.53 This treatment has been extensively studied in cells in culture and lens models in which cataracts occur.38 In Figure 5, we demonstrate that retinas from the knockout mice have reduction in all retinal layers and a severe loss of outer segments and retinal ganglion cells. Significant structural damage in the knockout retinas was observed in the outer plexiform, ganglion cell, and inner nuclear layers, while other layers had less damage after HBO treatment.

In our study, we noticed that the effects of HBO on knockout mice were more apparent in the central retina. The retina is a highly specialized tissue that integrates the light signal into the neural signal. In humans, this explains why some diseases affect different regions preferentially, as in age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.54,55

After HBO, we observed a more prevalent loss of photoreceptor outer segments, which was greater in the central region of the retina. Loss of outer segments plays an important role in age-related macular degeneration pathophysiology.56 Human age-related macular degeneration provides a good example of how different areas of the retina contain different structures and may show various responses to stress.

Retinopathy of prematurity, a vasoproliferative disease, is a potentially blinding disorder of premature infants.57 The retinopathy of prematurity model is known to cause vessel leakage. The PKCγ-knockout model has no such phenotype.

Glutathione peroxidase 3 catalyzes the reduction of hydrogen peroxide and protects cells against oxidative damage.38 The peripheral retina contains larger amounts of glutathione peroxidase 3 than the central retina, which could explain why depletion of glutathione by HBO affected the central retina more than the peripheral retina.58 The central retina is also more abundant in neuronal axons, ganglion cells, and neuron filaments.58

At present, little is known of the specific function of individual gap junctions in the retina. Earlier studies have shown that gap junctions are located between the rod bipolar cells and AII type amacrine cells.59 Rod bipolar cells do not make direct connections with ganglion cells. Neural signals first pass to AII type amacrine cells and AII type cells make synapses with the ganglion cells. In a connexin 36 knockout model, there was no AII/AII or AII/bipolar coupling, which demonstrated that the presence of connexin 36 was essential for normal coupling in rods.60

Protein kinase Cγ phosphorylates gap junction proteins, which results in disassembly of gap junction plaques and therefore in decreases in gap junction activity. We have shown that the presence of PKCγ is essential for normal functioning and organization of the retina, and we speculate that some of the causes of the HBO stress damage are the loss of control by PKCγ on gap junction activity and disassembly in response to stress. Because PKCγ is vital to stress protection in the retina, care should be given when treating patients with HBO. Screening for SCA14, for example, could prevent HBO-induced damage to the retina. In conclusion, these data demonstrate that PKCγ-knockout mice are more sensitive to retinal damage due to HBO than control mice, particularly in the central retina.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by grants NEI-RO1-13421 (Dr Takemoto); EY02027 and EY04803 (R24) (Dr Giblin); and EY07158 (Dr Sitaramayya) from the National Eye Institute, the National Institutes of Health. This is publication No. 05-96-5 from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Takemoto had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

References

- 1.Ripps H. Cell death in retinitis pigmentosa: gap junctions and the “bystander” effect. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74(3):327–336. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naus CC, Ozog M, Bechberger J, Nakase T. A neuroprotective role for gap junctions. Cell Commun Adhes. 2001;8(46):325–328. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frantseva MV, Kokarovtseva L, Perez Velazquez JL. Ischemia-induced brain damage depends on specific gap-junctional coupling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(4):453–462. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cusato K, Bosco A, Rozenthal R, et al. Gap junctions mediate bystander cell death in developing retina. J Neurosci. 2003;23(16):6413–6422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06413.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schütte M, Chen S, Buku A, Wolosin J. Connexin 50, a gap junction protein of macroglia in the mammalian retina and visual pathway. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66(5):605–613. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang H, Li H, He S. Identification of connexin 50 and 57 mRNA in A-type horizontal cells of the rabbit retina. Cell Res. 2005;15(3):207–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massey SC, O'Brien J, Trexler E, et al. Multiple neuronal connexins in the mammalian retina. Cell Commun Adhes. 2003;10(46):425–430. doi: 10.1080/cac.10.4-6.425.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin D, Takemoto DJ. Oxidative activation of protein kinase Cγ through the C1 domain. J Biol Chem. 2005;80(14):13682–13693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin D, Lobell S, Jewell A, Takemoto DJ. Differential phosphorylation of connexin 46 and connexin 50 by H2O2 activation of protein kinase Cγ. Mol Vis. 2004;10:688–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin D, Boyle DL, Takemoto DJ. IGF-1 induced phosphorylation of connexin 43 by PKCγ: regulation of gap junctions in rabbit lens epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(3):1160–1168. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosinsky GE, Nicholson BJ. Structural organization of gap junction channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711(2):99–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newton AC. Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(48):28495–28498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampe PD, TenBroek EM, Burt JM, Kurata WE, Johnson RG, Lau AF. Phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368 by protein kinase C regulates gap junctional communication. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(7):1503–1512. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen TA, Takemoto LJ, Takemoto DJ. Inhibition of gap junction activity through the release of the C1B domain of protein kinase Cγ (PKCγ) from 14-3-3: identification of PKCγ-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(50):52714–52725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solan JL, Lampe PD. Connexin phosphorylation as a regulatory event linked to gap junction channel assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711(2):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saleh SM, Takemoto DJ. Overexpression of protein kinase Cγ inhibits gap junction intercellular communication in the lens epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71(1):99–102. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner LM, Saleh SM, Boyle DJ, Takemoto DJ. Effect of protein kinase Cγ on gap junction disassembly in lens epithelial cells and retinal cells in culture. Mol Vis. 2002;8:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett M, Lin D, Akoyev V, Willard L, Takemoto D. Protein kinase C epsilon activates lens mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV during hypoxia. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86(2):226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.10.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronowski J, Grotta JC, Strong R, Waxham MN. Interplay between the gamma isoform of PKC and calcineurin in regulation of vulnerability to focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20(2):343–349. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katsura K, Kurihara J, Siesjo BK, Wieloch T. Acidosis enhances translocation of protein kinase C but not Ca+2 /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II to cell membranes during complete cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 1999;849(12):119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soong BW, Paulson HL. Spinocerebellar ataxias: an update. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20(4):438–446. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3281fbd3dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen DH, Brkanac Z, Verlinde CL, et al. Missense mutations in the regulatory domain of PKCγ: a new mechanism for dominant nonepisodic cerebellar ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(4):839–849. doi: 10.1086/373883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlak MH, Sinke RJ, Rabelink GM, Kremer BP, van de Warrenburg BP. Novel PRKCG/ SCA14 mutation in a Dutch spinocerebellar ataxia family: expanding the phenotype. Mov Disord. 2006;21(7):1025–1028. doi: 10.1002/mds.20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seki T, Adachi N, Ono Y, et al. Mutant protein kinase Cγ found in spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 is susceptible to aggregation and causes cell death. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(32):29096–29106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin D, Takemoto DJ. Protection from ataxia-linked apoptosis by gap junction inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362(4):982–987. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin D, Shanks D, Prakash O, Takemoto DJ. Protein kinase C γ mutations in the C1B domain cause caspase-3-linked apoptosis in lens epithelial cells through gap junctions. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85(1):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Brien JJ, Li W, Pan F, Keung J, O'Brien J, Massey SC. Coupling between A-type horizontal cells is mediated by connexin 50 gap junctions in the rabbit retina. J Neurosci. 2006;26(45):11624–11636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2296-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zahs KR, Ceelen PW. Gap junctional coupling and connexin immunoreactivity in rabbit retinal glia. Vis Neurosci. 2006;23(1):1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0952523806231018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson K, Bruun A, Ehinger B. Gap junction protein connexin 43 is heterogeneously expressed among glial cells in the adult rabbit retina. J Comp Neurol. 1999;407(3):395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen-Bienhold U, Dermietzel R, Weiler R. Distribution of connexin 43 immunoreactivity in the retinas of different vertebrates. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396(3):310–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zampighi GA. Distribution of connexin 50 channels and hemichannels in lens fibers: a structural approach. Cell Commun Adhes. 2003;10(46):265–270. doi: 10.1080/cac.10.4-6.265.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srinivas M, Kronengold J, Bukauskas FF, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. Correlative studies of gating in Cx46 and Cx50 hemichannels and gap junction channels. Biophys J. 2005;88(3):1725–1739. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujisawa N, Ogita K, Saito N, Nishizuka Y. Expression of protein kinase C subspecies in rat retina. FEBS Lett. 1992;309(3):409–412. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80818-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bazan HE, Dobard P, Reddy ST. Calcium and phospholipid-dependent protein kinase C, and phosphatidylinositol kinase: two major phosphorylations systems in the cornea. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6(5):667–673. doi: 10.3109/02713688709034829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Negishi K, Kato S, Teranishi T. Dopamine cells and rod bipolar cells contain protein kinase C-like immunoreactivity in some vertebrate retinas. Neurosci Lett. 1988;94(3):247–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greferath U, Grünert U, Wässle H. Rod bipolar cells in the mammalian retina show protein kinase C-like immunoreactivity. J Comp Neurol. 1990;301(3):433–442. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborne NN, Barnett NL, Morris NJ, Huang FL. The occurrence of three isoenzymes of protein kinase C (α, β and γ) in retinas of different species. Brain Res. 1992;570(12):161–166. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90577-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Padgaonkar VA, Leverenz VR, Dang L, Chen S, Pelliciccia S, Giblin FJ. Thioredoxin reductase may be essential for the normal growth of hyperbaric oxygentreated human lens epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79(6):847–857. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinkovic A, Smolle-Juettner FM, Krunic B, Marinsekz M. Severe carbon monoxide poisoning treated by hyperbaric oxygen therapy: a case report. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18(3):211–214. doi: 10.1080/08958370500434289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nighoghossian N, Trouillas P. Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of acute isch-aemic stroke: an unsettled issue. J Neurol Sci. 1997;150(1):27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)05398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang YH, Chen PL, Tai MC, Chen CH, Lu DW, Chen JT. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy ameliorates the blood-retinal barrier breakdown in diabetic retinopathy. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34(6):584–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowers BJ, Wehner JM. Ethanol consumption and behavioral impulsivity are increased in protein kinase Cγ null mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21(21):RC180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-j0004.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narita M, Mizoguchi H, Suzuki T, et al. Enhanced mu-opioid responses in the spinal cord of mice lacking protein kinase Cγ isoform. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(18):15409–15414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan F, Mills SL, Massey SC. Screening of gap junction antagonists on dye coupling in the rabbit retina. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24(4):609–618. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ciolofan C, Li XB, Olson C, et al. Association of connexin36 and zonula occludens-1 with zonula occludens-2 and the transcription factor zonula occludens-1-associated nucleic acid-binding protein at neuronal gap junctions in rodent retina. Neuroscience. 2006;140(2):433–451. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cuntz H, Haag J, Forstner F, Segev I, Borst A. Robust coding of flow-field parameters by axo-axonal gap junctions between fly visual interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(24):10229–10233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703697104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dedek K, Schultz K, Pieper M, et al. Localization of heterotypic gap junctions composed of connexin45 and connexin36 in the rod pathway of the mouse retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(6):1675–1686. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Correia SS, Duarte CB, Faro CJ, Pires EV, Carvalho AL. Protein kinase Cγ associates directly with the GluR4-α-amino-3hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptor subunit: effect on receptor phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(8):6307–6313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramakers GM, Gerendasy DD, de Graan PN. Substrate phosphorylation in the protein kinase Cγ knockout mouse. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(4):1873–1874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giordano G, Sanchez-Perez AM, Burgal M, Montoliu C, Costa LG, Felipo V. Chronic exposure to ammonia induces isoform-selective alterations in the intracellular distribution and NMDA receptor-mediated translocation of protein kinase C in cerebellar neurons in culture. J Neurochem. 2005;92(1):143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perez Velazquez JL, Frantseva MV, Naus CC. Gap junctions and neuronal injury: protectants or executioners? Neuroscientist. 2003;9(1):5–9. doi: 10.1177/1073858402239586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farahani R, Pina-Benabou MH, Kyrozis A, et al. Alterations in metabolism and gap junction expression may determine the role of astrocytes as “good samaritans” or executioners. Glia. 2005;50(4):351–361. doi: 10.1002/glia.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohsawa M, Narita M, Mizoguchi H, Cheng E, Tseng LF. Reduced hyperalgesia induced by nerve injury, but not by inflammation in mice lacking protein kinase Cγ isoform. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429(13):157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zarbin MA. Current concepts in pathogenises of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):598–614. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owsley C, Jackson GR, Cideciyan AV, et al. Psychophysical evidence for rod vulnerability in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(1):267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ethen CM, Reilly C, Feng X, Olsen TW, Ferrington DA. The proteome of central and peripheral retina with progression of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(6):2280–2290. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muñoz B, West SK. Blindness and visual impairment in the Americas and the Caribbean. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(5):498–504. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharon D, Blackshaw S, Cepko CL, Dryja TP. Profile of the genes expressed in the human peripheral retina, macula, and retinal pigment epithelium determined through serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(1):315–320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012582799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Söhl G, Güldenagel M, Traub O, Willecke K. Connexin expression in the retina. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;32(1):138–145. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feigenspan A, Janssen-Bienhold U, Hormuzdi S, et al. Expression of connexin 36 in cone pedicles and OFF-cone bipolar cells of the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2004;24(13):3325–3334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5598-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]