Abstract

Purpose: Evidence-based consumer information is a prerequisite for informed decision making. So far, there are no reports on the quality of consumer information brochures on osteoporosis. In the present study we analysed brochures on osteoporosis available in Germany.

Method: All printed brochures from patient and consumer advocacy groups, physician and governmental organisations, health insurances, and pharmaceutical companies were initially collected in 2001, and updated in December 2004. Brochures were analysed by two independent researchers using 37 internationally proposed criteria addressing evidence-based content, risk communication, transparency of the development process, and layout and design.

Results: A total of 165 brochures were identified; 59 were included as they specifically targeted osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Most brochures were provided by pharmaceutical companies (n=25), followed by health insurances (n=11) and patient and consumer advocacy groups (n=11). Quality of brochures did not differ between providers. Only 1 brochure presented lifetime risk estimate; 4 mentioned natural course of osteoporosis. A balanced report on benefit versus lack of benefit was presented in 2 brochures and on benefit versus adverse effects in 8 brochures. Four brochures mentioned relative risk reduction, 1 reported absolute risk reduction through hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Out of 28 brochures accessed in 2004 10 still recommended HRT without discussing adverse effects. Transparency of the development process was limited: 25 brochures reported publication date, 26 cited author and only 1 references. In contrast, readability and design was generally good.

Conclusion: The quality of consumer brochures on osteoporosis in Germany is utterly inadequate. They fail to give evidence-based data on diagnosis and treatment options. Therefore, the material is not useful to enhance informed consumer choice.

Keywords: pamphlets, osteoporosis/prevention and control, decision making, evidence-based medicine

Abstract

Ziel: Evidenzbasierte Informationen sind die Voraussetzung für informierte Entscheidungen von Verbrauchern bzw. Patienten. Die Qualität von Verbraucher-Informationsbroschüren zum Thema Osteoporose ist bislang nicht untersucht. In der vorliegenden Analyse wurde geprüft, ob die in Deutschland verfügbaren Broschüren geeignet sind, informierte Entscheidungen zu begünstigen.

Methoden: Selbsthilfegruppen und Verbrauchervertretungen, Gesundheitsministerien, Fachgesellschaften, Krankenkassen und Pharmafirmen wurden um Zusendung ihrer Osteoporosebroschüren gebeten. Eine erste Sammlung wurde 2001 durchgeführt, die Aktualisierung erfolgte im Dezember 2004. Die Beurteilung der eingeschlossenen Broschüren erfolgte durch zwei, voneinander unabhängige Untersucher anhand von 37 Kriterien zu Evidenzbasierung, Risikokommunikation, Transparenz des Entwicklungsprozesses, Layout und Gestaltung.

Ergebnisse: Insgesamt wurden 165 Broschüren identifiziert; 59 erfüllten die vorab definierten Einschlusskriterien. Die Mehrzahl wurde von Pharmafirmen herausgegeben (n=25), gefolgt von Krankenkassen (n=11) und Selbsthilfegruppen und -verbänden (n=11). Die Broschüren der verschiedenen Anbieter unterschieden sich nicht in ihrer Qualität. Nur 1 Broschüre präsentierte Angaben zum Lebenszeitrisiko; in nur 4 Broschüren wurde der natürliche Verlauf der Osteoporose erwähnt. Eine ausgewogene Darstellung von Nutzen und fehlendem Nutzen bzw. Nutzen und unerwünschten Wirkungen von Therapieoptionen war in nur 2 bzw. 8 Broschüren gegeben. Vier Broschüren gaben die relative Risikoreduktion einer Therapieoption an, nur 1 Broschüre führte eine absolute Risikoreduktion durch Hormonersatztherapie (HET) an. In 10 von 28 im Jahr 2004 identifizierten Broschüren wurde immer noch die HET als Behandlungsoption empfohlen ohne die adversen Effekte zu diskutieren. Die Transparenz des Entwicklungsprozesses der Broschüren war gering: nur 25 Broschüren gaben das Publikationsdatum an, 26 nannten den Autor und nur 1 gab Literaturreferenzen an. Demgegenüber waren die Lesbarkeit und die Gestaltung durchgehend gut.

Schlussfolgerung: Die Qualität von Verbraucher-Informationsbroschüren zu Osteoporose in Deutschland ist völlig unzureichend. Sie sind nicht geeignet, informierte Entscheidungen zu unterstützen.

Introduction

Recently, osteoporosis has become an issue increasingly covered by disease awareness campaigns. A popular example is the exhibition by the former Benetton photographer Olivero Toscani [1], displaying portraits of nude people, elderly and younger, suffering from osteoporosis. Such campaigns have been blamed as disease mongering [2]. There is no doubt that people require more information for decision making on preventive or treatment options. Ethical guidelines demand that evidence-based, clear and unbiased information are offered and made available to all patients and consumers [3]. Consumers' needs should be targeted, and best available evidence should be prepared using principles of risk communication and plain language [4], [5], [6].

Information brochures on osteoporosis prevention and treatment are widespread and readily available. Their suitability to support consumer decision making is not known. Therefore, we surveyed publicly available information brochures on osteoporosis in Germany using evidence-based criteria.

Methods

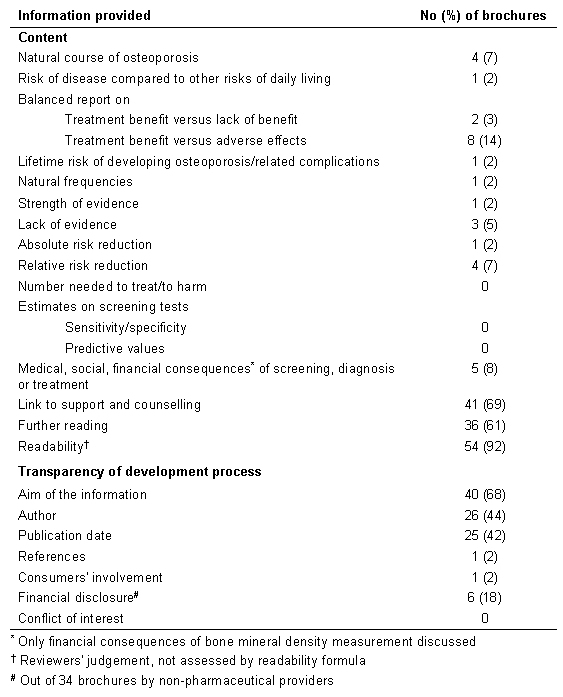

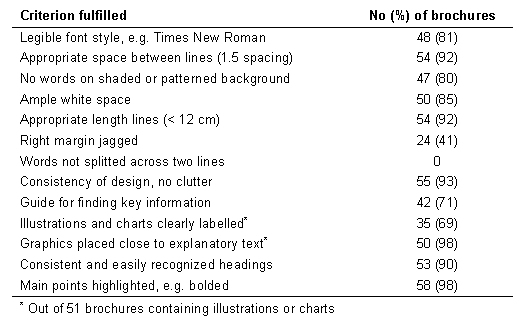

Brochures were initially collected in 2001, an update was made in December 2004. Written request was sent to patient and consumer advocacy groups, government organisations, medical associations, health insurances, and pharmaceutical companies. An internet search was performed in order to identify additional sources. Brochures were suitable for inclusion if they explicitly addressed patients or consumers, did not only present nutritional advice and did not cost more than € 3. Two reviewers (GM and AS) independently assessed the brochures, discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Thirty-seven criteria (Table 1 and Table 2) addressing content (n=17), transparency of the development process (n=7), layout and design (n=13) were used. The criteria were derived from publications by the General Medical Council of the United Kingdom [3] and the Harvard School of Public Health [5], and from former consumer information analyses [7], [8] and own work [6], [9].

Table 1. Content and transparency of the development process of 59 German consumer information brochures on osteoporosis.

Table 2. Layout and design of 59 German consumer information brochures on osteoporosis.

Results

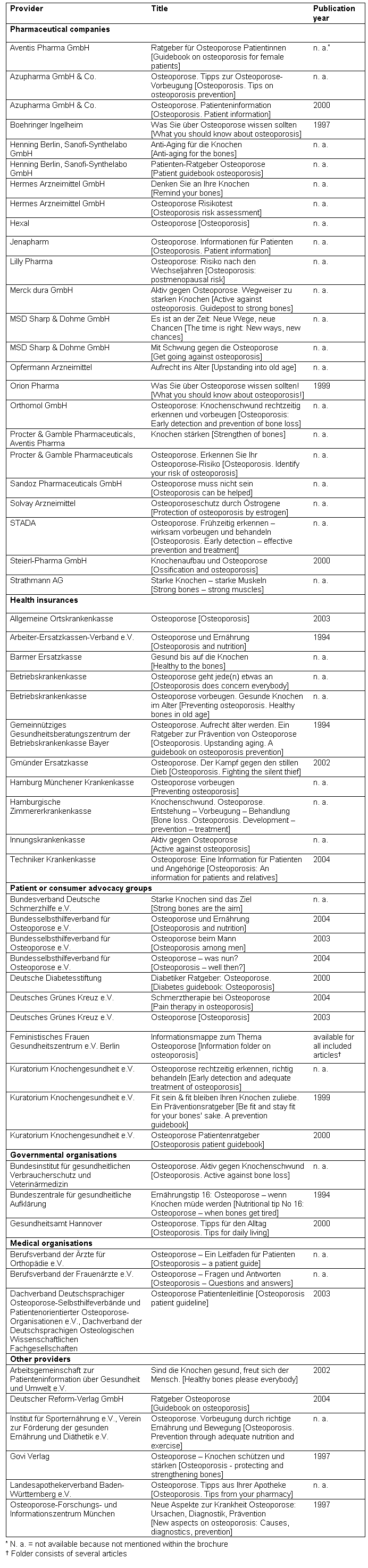

A total of 165 brochures were identified, and 59 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Twenty-eight brochures were excluded since they cost more than € 3 or did not explicitly address patients or consumers, 66 brochures did not specifically target osteoporosis prevention and treatment or only marginally discuss osteoporosis, and 12 brochures were replaced by an update in 2004. A list of excluded brochures is available from the authors on request. Table 3 displays the included material. Most brochures were provided by pharmaceutical companies (n=25), followed by health insurances (n=11), patient and consumer advocacy groups (n=11), government (n=3), medical organisations (n=3), and other providers (n=6). Independent agreement between the assessors was 97.9%. Table 1 shows the results of the analysis of the brochures' content and transparency of the development process. Remarkably, 10 out of 28 brochures accessed in 2004 still recommended hormone replacement therapy (HRT) without discussion of increased overall risk through venous thromboembolism, heart attacks, strokes, and breast cancer [10]. At that time, the Drug Commission of the German Medical Association had already advised doctors to prescribe HRT only for particularly severe menopausal symptoms [11].

Table 3. Brochures included in the review (n=59).

If mentioned, disease prevalence was commonly presented in a manner that is misleading such as “at least 6 to 8 million Germans suffer from osteoporosis” or “it affects every third woman aged over 50 years”. Only 1 brochure displayed the lifetime risk of hip fractures, the proportion of elderly remaining free from hip fracture, and the absolute risk reduction through HRT. Relative risk reduction was presented in 4 brochures, all referring to hip fracture reduction through external hip protectors. Financial consequences of screening on bone mineral density were mentioned in 5 brochures. The procedure is not covered by the German health insurances. Medical and social consequences of screening, diagnosis and treatment have not been discussed. All except 1 brochure failed to involve consumers within the development process.

Transparency of the development process was poor. None of the brochures provided a declaration on conflict of interest. References were presented only by 1 brochure. Less than half of the material mentioned author and publication date.

In contrast, layout and design criteria were largely fulfilled (Table 2).

Quality of brochures from patient and consumer advocacy groups did not differ from those from pharmaceutical companies and other providers. However, our sample may have been too small for such comparisons.

Discussion

Our results show that consumer brochures on osteoporosis prevention and treatment available in Germany do not fulfil internationally suggested criteria on evidence-based information and risk communication. Overall, the material assessed is not useful to enhance informed decision making since it is highly persuasive and misleading. Our results are supported by former studies on consumer information materials targeting other health issues. A recent analysis demonstrated that information on bone mineral density measurement available to consumers on the internet strongly differs from evidence coming from HTA reports. Consumer information was inaccurate and incomplete [12]. Analyses of pamphlets [8] and websites [7] on mammographic screening found that the information was poor and severely biased. In a previous study we demonstrated the deficiencies of consumer brochures dealing with screening for colorectal cancer [9]. Consequently, we developed an evidence-based information tool [13].

In recent years, osteoporosis has been recognised as an important area of research and intervention. Numerous preventive and treatment options have been suggested [14]. For consumers several issues of uncertainty remain such as limited predictive validity of bone mineral density measurement, marginal benefits of medication, and unknown long-term effects [15]. Therefore, osteoporosis prevention and treatment is a typical area for evidence based consumer information aimed to enhance decision making based on individual risk of disease, best external evidence and personal preferences. Ideally, such material should be produced by medical associations or advocacy groups. Suggestions have been made how to develop evidence-based consumer information [6], [16]. If these suggestions are feasible and acceptable beyond university institutions is still unknown.

Notes

Authorship

All authors declare that they have substantially contributed to this paper and that they agree with the content and format of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Gabriele Meyer, Anke Steckelberg, and Ingrid Mühlhauser all declare that they have no financial disclosures to make in relation to this paper.

There were no sponsors for this project.

References

- 1.Deutsches Grünes Kreuz. [cited 2006 Oct 31];Aufklärung mit Aktaufnahmen [Internet] 2005 Available from: http://www.dgk.de/web/dgk_content/de/toscani_austellung.htm.

- 2.Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering. BMJ. 2002;324(7342):886–891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.General Medical Council. [cited 2006 Oct 31];Protecting patients, guiding doctors. Seeking patients' consent: the ethical considerations [Internet] 1998 Available from: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/archive/library/consent.asp.

- 4.Coulter A. Evidence based patient information. is important, so there needs to be a national strategy to ensure it. BMJ. 1998;317(7153):225–226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7153.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudd RE. How to create and assess print materials [Internet] Harvard School of Public Health: Health Literacy Studies; 2005. [cited 2006 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/healthliteracy/materials.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steckelberg A, Berger B, Kopke S, Heesen C, Mühlhauser I. Kriterien für evidenzbasierte Patienteninformationen. [Criteria for evidence-based patient information] Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitätssich. 2005;99(6):343–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorgensen KJ, Gotzsche PC. Presentation on websites of possible benefits and harms from screening for breast cancer: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2004;328(7432):148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7432.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slaytor EK, Ward JE. How risks of breast cancer and benefits of screening are communicated to women: analysis of 58 pamphlets. BMJ. 1998;317(7153):263–264. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7153.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steckelberg A, Balgenorth A, Mühlhauser I. Analyse von deutschsprachigen Verbraucher-Informationsbroschüren zum Screening auf kolorektales Karzinom. [Analysis of German language consumer information brochures on screening for colorectal cancer] Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitätssich. 2001;95(8):535–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgermeister J. Head of German medicines body likens HRT to thalidomide. BMJ. 2003;327(7418):767. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green CJ, Kazanjian A, Helmer D. Informing, advising, or persuading? An assessment of bone mineral density testing information from consumer health websites. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(2):156–166. doi: 10.1017/s0266462304000935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steckelberg A, Mühlhauser I. [cited 2006 Oct 31];Darmkrebs-Früherkennung. [Colorectal cancer screening] [Internet] 2003 Available from: http://gesundheit.chemie.uni-hamburg.de/upload/CRC_Broschuere_as_final.pdf.

- 14.Sambrook P, Cooper C. Osteoporosis. Lancet. 2006;367(9527):2010–2018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68891-0. Erratum in: Lancet. 2006;368(9529):28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, Maalouf N, Gottschalk FA, Pak CY. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1294–1301. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sänger S, Lang B, Klemperer D, Thomeczek C, Dierks ML. Manual Patienteninformation. Empfehlungen zur Erstellung evidenzbasierter Patienteninformationen. Berlin: 2006. (äzq Schriftenreihe; 25). Available from: http://www.patienten-information.de/content/download/manual_patienteninformation_04_06.pdf. [Google Scholar]