Abstract

Objective

To evaluate a hospice-based advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE).

Design

Two years of data gathered from student evaluation forms and reflective journals were analyzed.

Assessment

Students completed reflective journals and expressed a high level of satisfaction with the hospice-based learning experience. They gained a better understanding of end-of-life care provided by a hospice and the pharmacist's role in optimizing supportive care for patients receiving hospice care.

Conclusion

Hospice-based APPEs can provide a rich interdisciplinary learning environment for pharmacy students interested in developing knowledge, attitudes, and skills to effectively manage the pharmacotherapy of patients receiving end-of-life care.

Keywords: assessment, advanced pharmacy practice experience, hospice care, reflective journals

INTRODUCTION

The first hospice in the United States was established in Connecticut in 1974. It began as a demonstration project supported by a National Cancer Institute grant to provide palliative care to terminally ill patients in their homes and was an inspiring success.

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) reported that 4,500 hospice programs provided care to over 1.3 million patients in 2006. Thirty-six percent of Americans who died that year received end-of-life care from a hospice and 56% of hospice patients had a terminal illness other than cancer. Additional information addressing patient demographics, median length of stay, and the profit status of hospice programs are provided in the NHPCO report.1

Pharmacotherapy is an important component of end-of-life care. Pharmacist involvement in palliative care settings has been a topic of interest since the mid-1970s and continues to be addressed in pharmacy literature.2-19 Our College began offering an elective hospice-based advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) to doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) students in 1996. This article provides a description of the APPE and student assessment of their learning experience.

DESIGN

The Hospice of the Red River Valley is a free-standing nonprofit entity that has provided end-of-life home care in a community of 150,000 residents since 1981. In 2003, a local hospital opened an 8-bed palliative care unit to provide inpatient care for patients requiring more intense symptomatic support. The North Dakota State University College of Pharmacy began offering an elective APPE to P4 students in 1996.

The goal of the APPE was to increase student understanding of hospice care and the pharmacist's role in optimizing the pharmacotherapy of hospice patients. Students were supervised by a clinical specialist in oncology with a faculty appointment at the College who volunteered as a consultant, by the nurse clinical education coordinator, and by the nurse clinical manager.

A unique aspect of the hospice APPE was the opportunity for students to develop knowledge, attitudes, and skills to effectively interact with patients and families dealing with the emotions surrounding an impending death. The 1969 landmark work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross clearly established that patients dealing with terminal diagnoses face unique challenges.20 Fear, denial, anger, and depression are some of the intense emotions experienced when patients learn they have an incurable illness that is no longer responsive to therapy. The ability of caregivers to identify the emotional stress patients experience and assist them to more effectively cope with the knowledge of their impending death is a valued skill. Hospices are committed to providing an interdisciplinary team approach to provide patients with physical, emotional, and spiritual care. Social workers, chaplains, and nurses are able and willing to provide pharmacists with the insights and support needed to deal effectively with the body, mind, and soul issues faced by patients.

Pharmacy students participated in activities to increase their understanding of hospice care, including attending new employee orientation, classes on pain management, and weekly interdisciplinary care conferences. They also accompanied nurses on patient visits to determine patients' eligibility for admission to hospice and to evaluate and provide follow-up care. Finally, students accompanied chaplains making home visits to provide spiritual or bereavement support.

To increase student understanding of a pharmacist's role in hospice care, students reviewed the medications of patients admitted to hospice and presented their evaluations to the pharmacist preceptor, provided drug information (including recommendations for changes in medication regimens to hospice staff, patients, and caregivers), and participated in assigned projects. Student projects included writing a draft of a document related to hospice care (eg, a medication cost analysis document, a manuscript describing the conversion of a patient's morphine from intrathecal to oral administration). Several projects provided opportunities for students to participate in scholarly activities such as publishing a case report, submitting a poster for presentation at a professional meeting, and participating in a research project evaluating the absorption of methadone applied topically to hospice patients.21-23 In addition, students were required to write a journal with reflections about their hospice experiences and review a published journal article germane to hospice care.

At the end of the 5-week experience, students were required to complete an evaluation of the APPE and comment on its strengths and weaknesses. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

ASSESSMENT

Evaluation Form Ratings

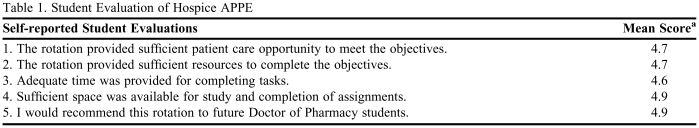

Evaluations of the APPE site for academic years 2006 and 2007 are presented in Table 1. The average daily census during the evaluation period was 200 patients. Data from 18 student evaluations were analyzed. Mean Likert scores and student comments in reflective journals documented that students valued the learning opportunities provided by the APPE.

Table 1.

Student Evaluation of Hospice APPE

a Score based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Reflective Journal Comments

Pharmacy students often commented on how the APPE affected them personally and professionally. One student stated that the hospice experience “helped in developing medication knowledge, communication skills, and most of all compassion for patients and their families. I would recommend this rotation to other pharmacy students.” Another student wrote that “this rotation should be mandatory. As a pharmacist we really don't have the opportunity to see the difference that we make in a patient's life. Until you get to go into their home and actually see them and their family, it's hard to put into perspective the role that we play. So far this has been one of the best experiences I've ever had.”

Some students felt that even though this was not a standard pharmacy APPE, it was beneficial. One student wrote: “I have had many opportunities to contribute my pharmacy knowledge at hospice, and even if I wasn't counting pills or counseling on proper use, I still made a difference in the care of the patient. ”Another student felt that a patient visit with a chaplain had a big impact on her personally: “[This visit] really made me re-evaluate my own faith. I think I would definitely like to go on another chaplain visit.” Students regularly wrote in their journals that the hospice APPE was a great experience for them. A student stated that he would “recommend continuing the experience for future PharmD students and others that are involved in healthcare. It has taken away some of the misconceptions that I had about dying and specifically what to say to those family members who have a loved one that is dying. I have gained some valuable experience over the last 5 weeks that will stick with me and last for a lifetime.”

During patient home visits, students commonly answered medication-related questions from nurses and patients and educated patients and families on the proper use of their medications. They assisted in setting up patient medication “minders” and have filled insulin syringes. A student noted in her reflective journal: “As a pharmacist, I can see an opportunity to impact many patients with the proper management of medication in this stage of life in that there are many unnecessary prescriptions that are not indicated or the endpoint of therapy has long been reached.”

DISCUSSION

Americans' acceptance of end-of-life care provided by hospice organizations has resulted in substantial growth of hospice care in the United States. Pharmacists' responsibility to provide care to hospice patients has grown commensurately. Student reflective journals and evaluations of hospice experiences documented that the APPE provided a rich interdisciplinary learning environment for pharmacy students interested in developing knowledge, attitudes, and skills to effectively manage the pharmacotherapy of patients receiving end-of-life care. The development of a hospice-based APPE was well received by students and hospice staff members.

Initially, some students questioned their role. A student wrote: “Right away I felt like I didn't belong there and was intruding on the family's privacy, but I started talking to his wife and felt more comfortable.” Another student wrote about being on a patient visit: “In some ways being there made me uncomfortable. I sometimes wonder what the patients are thinking about others being there, especially this patient, because she knows she is dying…I wonder if they are embarrassed or uncomfortable with my presence. I really hope not.” Also, some families do not understand the role of the pharmacy student on patient visits. After a patient asked why the pharmacy student was there, the student wrote: “She asked what my purpose was there. [The chaplain] and I told her that I was there to learn about patient care, review medications, and make suggestions or answer questions about medications and how to better the patient through medication management. She nodded in understanding.” Even though patients and students may not understand at first why students are there, students benefitted from the patient contact during patient visits, as a student noted: “To me [patient visits] are very interesting because you get to see first hand how the patient is really doing. They no longer become just a piece of paper sitting in front of you. You get to hear what concerns they have, how their pain is doing.”

While on the hospice APPE, students learned to shift their focus to palliative care. The goal of pharmacotherapy in many diseases is to prevent or slow a pathologic process before it becomes life threatening. On the hospice APPE, students may struggle when confronted with evaluating pharmacotherapy options for patients with advanced illnesses refractory to pharmacotherapy, as described in this student comment: “It was hard at first on this rotation to switch my way of thinking from curative treatment to comfort care. We are not taught this at pharmacy school, and I always had to remind myself in the beginning that the goals here are different.” Another student found it difficult to perform his typical pharmaceutical care plan review: “My hardest struggle with hospice care plans is to provide monitoring parameters in patients who do not get routine labs.” Students on the hospice APPE learned that “the focus of care…switches from a ‘cure it' state of mind to ‘help the patient with whatever they so choose' type of mentality.” One student wrote: “I often catch myself asking the question, ‘Why are we not trying to fix this problem?’ I am having somewhat of a hard time making myself think in a palliative manor [sic].”

Learning about the dying process and how to support dying people and their families was a large part of the hospice APPE. Students learned about the signs of impending death, a topic that is not covered in pharmacy school. A student noted that a patient “had mottling of the leg and arms and her respirations were labored and forceful. She was unresponsive but looked peaceful.” Pharmacy students sometimes were present when a patient died. One student wrote: “During our visit this morning he died. Wow. He died right while I was standing next to him. I can not explain how I felt but that I will remember that moment for the rest of my life. I got to help clean him up and help funeral home staff prepare him for transportation. Again I was so proud of helping care for him. It was a very satisfying feeling to see him die so comfortably.” Another student who was present when a patient died wrote: “He died this afternoon while we were there. This was the first time that I have seen a patient die. It was very hard to not be emotional as you watch and try to help the family with their loss. This was a very meaningful and memorable day here at hospice.” Students saw more than patients dying, however. They also had the chance to see patients living with terminal diseases. A student wrote: “I think the biggest misconception I had about this experience is that I expected to go on these visits and to see everyone on their death bed. This has not been the case. I met a 94-year-old lady who was able to get around and take care of herself.” Another student wrote: “In my mind, I envisioned the patients lying in bed not being able to function. This definitely wasn't the case!” Students on the hospice APPE had the opportunity to see people living with terminal diseases as well as patients facing imminent death.

A new APPE hospice site became available for students during the 2007-2008 academic year. The site employed an off-site medical director and clinical pharmacist. When students had medication questions, they were referred to these off-site clinicians. Meetings between the student and clinical pharmacist were not regularly scheduled. Student evaluations noted that the APPE did not provide them with a satisfactory learning experience because of the difficulty in having their general as well as specific patient medication questions addressed in a timely manner. Consequently, the site was not continued and led to our recommendation that the active participation of a hospice-affiliated pharmacist preceptor be a prerequisite for a hospice-based APPE.

CONCLUSION

Hospice programs have the potential to provide a rich interdisciplinary learning environment for pharmacy students interested in developing knowledge, attitudes, and skills to effectively manage the pharmacotherapy of patients receiving end-of-life care. Our evaluation supports further development of hospice-based advanced experiences for pharmacy students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are most grateful for the contributions of the dedicated Hospice of Red River Valley staff members and their patients for providing our students a valuable learning opportunity.

REFERENCES

- 1. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization's Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America - November 2007 Edition; Available at http://www.caringinfo.org/userfiles/File/2009%20NHPCO%20Outreach%20Guide/National%20Hospice%20%20Palliative%20Care%20Month%20Outreach/Media%20Outreach%20Documents/Background%20Documents%20-%20PDFs/NHPCO_Facts_and_Figures_Nov_2007.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2009.

- 2.Hammel MI, Trinca CE. Patient needs come first at Hillhaven Hospice: Pharmacy services essential for pain control. Am Pharm. 1978;NS18:655–7. doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(15)32666-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry JI, Pulliam CC, Caiola SM, Eckel FM. Pharmaceutical services in hospices. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1981;38:1010–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuBe JE. Hospice care and the pharmacist. US Pharmacist. 1981:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arter SG, Berry JI. The provision of pharmaceutical care to hospice patients: results of the national hospice pharmacist survey. J Pharm Care Pain Symptomatic Control. 1993;1:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipman AG, Berry JI. Pharmaceutical care of terminally ill patients. J Pharm Care Pain Symptomatic Control. 1995;3:31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diment MM, Evans BL. Implementation of a pharmaceutical care practice models for palliative care. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1995;48:228–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas C, Glare Paul A, Sykes JV. Contribution of a liaison clinical pharmacist to an inpatient palliative care unit. Palliative Med. 1997;11:209–16. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ASHP statement on the pharmacist's role in hospice and palliative care. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2002;59:1770–3. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.18.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rule AM. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists' pain management network. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2004;18:59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suh ES, Bartlett G, Inguanti M, Folstad J. Evaluation of a pharmacist pain management education program and associated medication use in a palliative care population. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004;61:277–80. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussainy SY, Beattie J, Nation RL, et al. Palliative care for patients with cancer: what are the educational needs of community pharmacists? Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:177–84. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, McPherson ML. Outcomes of recommendations by hospice pharmacists. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2006;63:2235–9. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill RR. Clinical pharmacy services in a home-based palliative care program. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64:806–10. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardoni JB. How pharmacy students learn to serve on the hospice team. Pharm Times. 1986:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron MF. Death and dying. Am J Pharm Educ. 1998;62:220–2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herndon CM, Fike DS, Anderson AC, Dole EJ. Pharmacy student training in United States hospices. Am J Hosp Palliative Care. 2001:181–6. doi: 10.1177/104990910101800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aragon FD, Forman WB, Dole EJ. Description of a palliative care/hospice clerkship for entry level doctor of pharmacy students. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002:515–7. doi: 10.1331/108658002763316978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herndon CM, Jackson K, Fike DS, Woods T. End-of-life care education in United States pharmacy schools. Am J Hosp Palliative Care. 2003:340–4. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kübler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York, NY: MacMillian; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sylvester RK, Lindsay SM, Schauer C. The conversion challenge: from intrathecal to oral morphine. Am J Hosp Palliative Care. 2004;21:143–7. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sylvester RK, Schauer C, Thomas J Weisenberger, Steen. An Evaluation of the Bioavailability of Methadone Administered Transdermally in Hospice Patients. American College of Clinical Pharmacy Spring Practice and Research forum 2007 Abst 69; Available at http://www.pharmacotherapy.org/pdf/Pharm2704e-ACCP_Spring_Abstracts.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2009.

- 23. Sylvester RK, Roden W, Roberg J, Smithson K. Student assessment of a hospice advanced practice experience. American Association Colleges of Pharmacy Annual Meeting, 200; Available at http://ajpe.org/view.asp?art=aj710360&pdf=yes. Accessed April 26, 2009.