Abstract

Objective

Determine the effectiveness of TIMER (Tool to Improve Medications in the Elderly via Review) in helping pharmacists and pharmacy students identify drug-related problems during patient medication reviews.

Methods

In a randomized, controlled study design, geriatric patient cases were sent to 136 pharmacists and 108 third-year pharmacy students who were asked to identify drug related-problems (DRPs) with and without using TIMER.

Results

Pharmacists identified more tool-related DRPs using TIMER (p = 0.027). Pharmacy students identified more tool-related DRPs using TIMER in the first case (p = 0.02), but not in the second.

Conclusion

TIMER increased the number of DRPs identified by practicing pharmacists and pharmacy students during medication reviews of hypothetical patient cases.

Keywords: medication therapy management, drug-related problems, elderly, community pharmacy

INTRODUCTION

Medicare Part D requires MTM for enrollees who use a high proportion of financial resources in the program.1 Pharmacists are challenged to find ways to effectively and efficiently provide MTM services, given the high volume of prescriptions that they dispense. While there are MTM plans that assist pharmacists, these services are not always available.2-3 Community pharmacists, who fill the vast majority of prescriptions, are in a unique position to provide important medication reviews.4-6 An MTM tool may provide pharmacists with a systematic approach for conducting medication reviews and improve efficiency.

MTM services can be especially valuable to older adults.7-8 The presence of polypharmacy and age-related physiological changes cause this population to experience more drug-related problems (DRPs).9 Medication errors consist of overuse, underuse, and misuse, and lead to more than 5% of hospital admissions in older adults.9-11 Between 14% and 23% of older adults receive a medication that should not have been prescribed for them,12-14 and 10% to 25% of patients have an adverse drug reaction or adverse drug event.15,16 However, some medications, such as statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, are under prescribed among older adults.17-21

In order to simplify medication reviews, screening tools have been developed. Available tools include Beer's list, Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders guidelines, and the Medication Appropriateness Index.22-28 These tools can rarely accommodate patients with multiple chronic diseases, multiple drug interactions, and/or organ-system insufficiency that may cause patient-specific medication problems. Medication reviews need to be done in a way that encompasses the whole patient, not just a particular disease, medication, or drug interaction. This complexity makes it nearly impossible to create a tool that is sufficiently specific and sensitive to identify drug therapy problems.28

In addition to practicing pharmacists, pharmacy students are trained to provide MTM,29,30 but there is currently no standardized approach used to provide MTM services or to identify DRPs.31,32 A tool may make the task of learning how to provide these services easier for pharmacy students and practicing pharmacists who are new to MTM. Having such a tool may also facilitate and improve the efficiency of identifying DRPs.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the Tool to Improve Medications in Elderly via Review (TIMER), a systematic approach to conducting medication reviews and improving pharmacists’ ability to identify important drug-related problems among older adults. The specific aim of this 2-part study was to compare the number and types of drug-related problems identified by practicing pharmacists (part 1) and pharmacy students (part 2) with and without using the TIMER.

METHODS

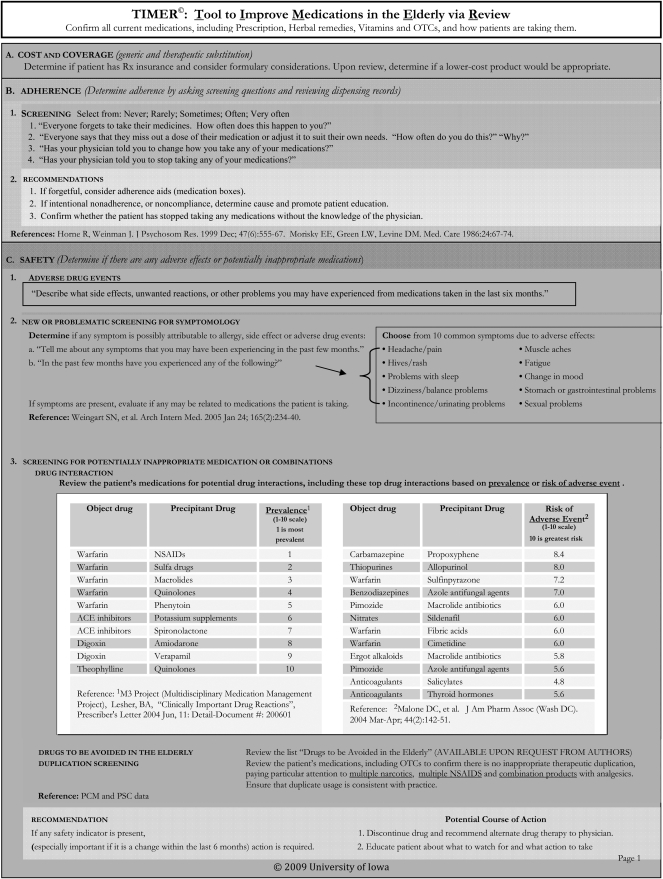

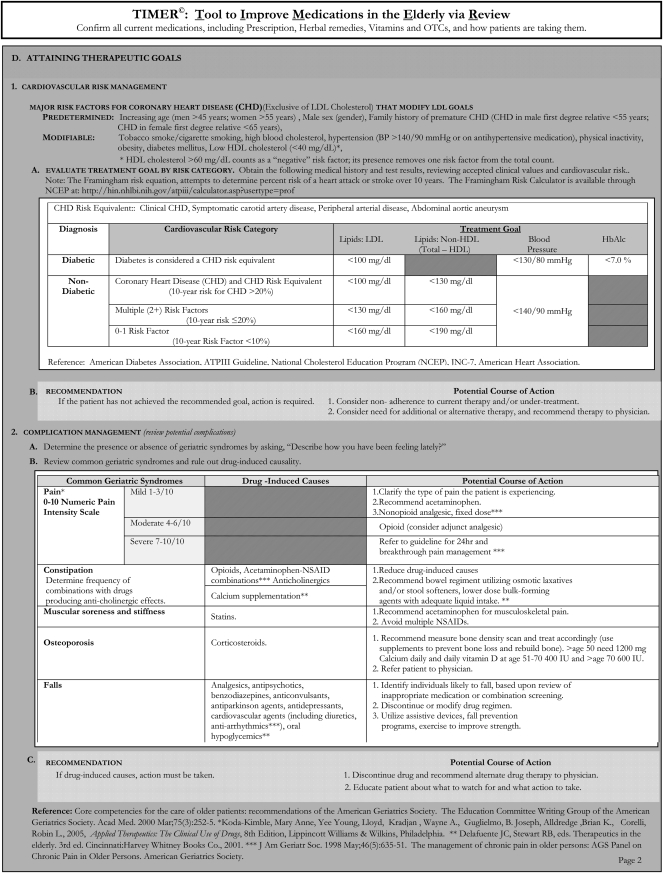

Development of the TIMER

TIMER is a guide for pharmacists and pharmacy students to follow when conducting medication reviews. TIMER was developed by 2 of the authors (KF and EC), with input from a consensus panel of 4 regional experts who reviewed the tool and provided feedback. Using a scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, reviewers rated each section of the TIMER on whether the content was evidence-based, important, helpful/useful, and understandable. Feedback from reviewers resulted in several improvements to TIMER, for example, including drug-drug interactions based on both prevalence and severity rather than just on severity, and reducing the symptom timeframe to several months.

An important assumption made in developing TIMER was that its users have conducted a patient medication history so that a complete medication list is available. TIMER has 4 sections including cost-effective drug selection, adherence, medication safety, and attaining therapeutic goals, and covers the most common medication issues that affect older adults. Specific reference to the 8 DRPs commonly used in practice-based research studies was not included because TIMER was intended to encourage pharmacists to look beyond those DRPs and consider patients’ symptomatology and complications among older adults.

Each of the 4 sections includes points to discuss with patients and suggested recommendations if a DRP is found. The section on cost-effective drug selection suggests generic and therapeutic substitution to ensure that patients are getting the most cost-effective medications. The section of adherence gives examples of how to question patients about adherence and provides specific recommendations. A section on medication safety addresses adverse drug effects, screening for symptomology, inappropriate medications, drug interactions, and Beer's criteria medications. When determining whether patients are attaining their therapeutic goals, TIMER contains guidance on cardiovascular risk reduction and complication management. The section on cardiovascular risk management outlines the major risk factors for coronary heart disease and evaluates treatment goals. The section on complication management identifies common complications seen in the geriatric population, how to screen for them, and recommendations for each complication (Appendix 1).

Evaluation of TIMER Via Written Cases

To evaluate TIMER, a 2-part randomized, controlled study was designed that involved practicing pharmacists and pharmacy students using the tool to assess hypothetical patient cases.

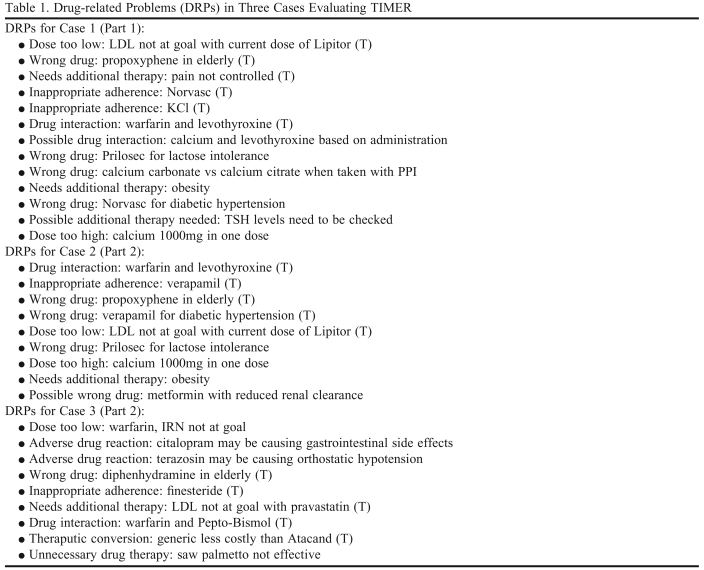

Patient Case 1 was developed by one of the authors (MA) and based on a case taken from IowaTeach, a University resource for faculty members to use in developing teaching activities. Both clinical and hypothetical patient cases are available in IowaTeach and many contain additional instructional materials such as test questions and teaching notes. Case 1 was an older adult presenting to a community pharmacist for MTM services. Two expert clinicians reviewed Case 1 and identified 13 DRPs, 6 of which were tool-related and 7 that were non-tool-related (Table 1). Tool-related DRPs were those covered in TIMER and non-tool-related DRPs were problems not included in TIMER.The non-tool-related DRPs identified by the experts were not eliminated from the case but were not expected to be affected because TIMER did not contain them.

Table 1.

Drug-related Problems (DRPs) in Three Cases Evaluating TIMER

Abbreviations: TIMER = Tool to Improve Medications in the Elderly via Review; (T) = Tool-related DRP. A Tool-related DRP is one that is included in TIMER.

Cases 2 and 3 were written by 2 of the authors (MC and JR). Both cases involved older adults presenting to pharmacists for MTM services. The authors identified 4 non-tool-related DRPs and 5 tool-related DRPs in their respective case, and this list later served as the key when coding DRPs (Table 1). Case 1 from the pharmacists study served as the basis for cases 2 and 3. The DRPs from case 1 were incorporated into cases 2 and 3, with substitution of medications. For example, warfarin interactions in cases 1 and 2 involved levothryoxin, while warfarin interactions in case 3 were caused by bismuth subsalicylate. Another example of modifications was the wrong drug used in the cases. In cases 1 and 2, the wrong drug was propoxyphene and in case 3 it was diphenhydrame: both are Beer's list drugs.

Part 1: Pharmacists’ Use of the TIMER

A randomized controlled study of practicing pharmacists who were members of a regional MTM network (Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana) was conducted and half of the pharmacists were randomly selected to receive TIMER. All pharmacists received a printed copy of case 1 and a response form with instructions to identify DRPs in the patient case and write SOAP notes including recommendations. A document of consent to participate was also included in the packet. Participants were asked to return all materials to the investigators and by doing so indicated their informed consent. IRB approval for this study was obtained.

The packet of materials was mailed to 136 pharmacists in mid-April 2007 and a follow-up postcard was sent to non-responders 2 weeks later. A second packet with the same materials was mailed again in mid-June to nonresponders and a follow-up postcard was sent 1 month later. Responses obtained by mid-August 2007 were included in the analysis. Demographic information obtained when the MTM network was formed was linked to the responses in this study. These data included age, practice years, gender, average hours spent in pharmacy per week, and state in which they practiced.

An investigator (AS) coded the pharmacists’ responses as either correctly identifying each of the 13 DRPs or not, using a pre-established set of coding rules. Only the DRPs were considered when coding the responses, and not the actions the pharmacist recommended. If a DRP was unclear, the study team reviewed it and consensus was reached. The data were entered into a spreadsheet and analyzed using SPSS. The 2 groups of pharmacists (those who received the TIMER and those who did not) were compared for age, years in practice, and hours worked per week using t tests, and for gender using the chi-square test. The numbers of tool-related and non-tool-related DRPs were summed for each respondent. The total number of tool-related and non-tool-related DRPs identified per study group were compared, controlling for gender and practice years. A chi-square test also was used to compare each tool-related DRP identified with whether the pharmacist had received the TIMER.

Part 2: Pharmacy Students’ Use of the TIMER

In the second part of the study, third-year pharmacy students enrolled in the Pharmacy Practice Laboratory course at University of Iowa College of Pharmacy were asked to identify DRPs in 2 cases, 1 using and 1 not using TIMER. IRB approval for this study was obtained. As seating was randomly assigned at the start of the course, students were already assigned to 54 groups of 2. Students were informed that their answers would not affect their grade for the course. Students reviewed a study information sheet containing all elements of informed consent. Their submission of answers indicated informed consent. For the first 30 minutes of class time, each group of 2 students was assigned 1 of 2 patient cases and asked to identify drug-related problems. For the next 30 minutes, each group was given a second case along with the TIMER and again asked to identify DRPs. Groups of 2 were randomly assigned to receipt of TIMER for 1 of the 2 cases.

The students were asked to provide their age, pharmacy grade point average (GPA), gender, laboratory section, and a unique identifier, which allowed for statistical comparisons to be made later without compromising students’ anonymity. Groups of 2 students were asked to list all DRPS that they could find in 30 minutes and state the action that would be taken for each DRP. As the objective was to determine whether TIMER improved students’ ability to identify DRPs, only the DRPs were considered during coding and not students’ proposed solutions.

Coding of responses was done by an investigator (SL) trained to examine the SOAP notes and identify the presence or absence of the DRPs. Each DRP was coded as either correctly identified or not correctly identified for each group. A set of coding rules for each case was developed by the investigator and reviewed by other investigators before coding was completed. The classification of a correct versus incorrect DRP was based on their written identification of a DRP, not necessarily how the student described it. For example, for the presence of nonadherence to verapamil in case 2, any mention of poor compliance with verapamil was coded as a “yes, the DRP was identified” whether the cause of noncompliance was attributed to side effect, inability to swallow, or patient thinking the drug did not work. Also, if poor compliance with another drug besides verapamil was identified, subjects were not given credit for identifying noncompliance with verapamil. Simply identifying the ADR of verapamil and constipation was not sufficient if compliance or patient education was not mentioned. Proposed actions or recommendations were not used to determine DRPs—the DRP had to be stated. If a DRP was unclear, the study team reviewed it and consensus was reached.

Results were entered into a spreadsheet and analyzed using SPSS. Subjects were divided into 2 study groups: those who received case 2 first and those who received case 3 first. Age, gender, and GPA of the student pharmacists in the 2 study groups were analyzed using chi-square and t tests. The number of tool and non-tool related DRPs identified by student groups were summed across both cases and used as dependent variables. Tool-related DRPs were those that were included in TIMER. The independent variables used in analyses were laboratory section of the student, whether TIMER was used, and patient case. A one-way ANOVA was used to calculate the difference in dependent variables between the 3 Pharmacy Practice Laboratory sections. Then the effect of TIMER and case on total tool-related and total non-tool-related DRPs identified was examined using 2-way ANOVA. We also analyzed the cases separately for significance of TIMER using 2-tailed t tests, as case was significant in the primary analysis. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Eighty-seven of the 136 practicing pharmacists participated in the study. Of these, 41 had been given the TIMER and 46 had not. The average age of participants was 37.0 ± 10.6 years; average time in practice was 13.0 ± 11.2 years; hours worked per week were 36.3 ± 11.2 hours, and 63.2% were female. There were no significant demographic differences between the 2 groups of pharmacists. Practice years and age were correlated (0.965), so age was not included in any further analyses.

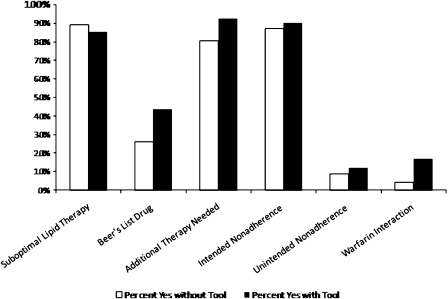

The average tool-related DRPs identified by the respondents was 3.4 ± 1.0 by those using the TIMER and 3.0 ± 1.0 for those not using the TIMER (t = −2.26, p = 0.027). The overall model predicting tool-related DRPs using practice years, gender, and TIMER use was significant (F = 6.53, p = 0.001). Gender and TIMER use were significant (p = 0.007 for both), while number of practice years was not significant (p = 0.44). There was no significant difference in the number of DRPs identified by pharmacists in Iowa compared to those in other states (p = 0.23). Both use of TIMER and practice years were associated with the number of non-tool-related DRPs identified (p = 0.027 and p = 0.030, respectively). When individual tool-related DRPs were analyzed according to use of TIMER, none showed a significant difference (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pharmacists’ Identification of Individual Tool-Related DRPs by Use of TIMER (Tool to Improve Medications in the Elderly via Review)

In part 2 of the study, the average age of the pharmacy students was 25 ± 4.2 years; average GPA was 3.3 ± 0.4; and 57.5% were female. There were no significant differences in demographics between the 2 groups of students.

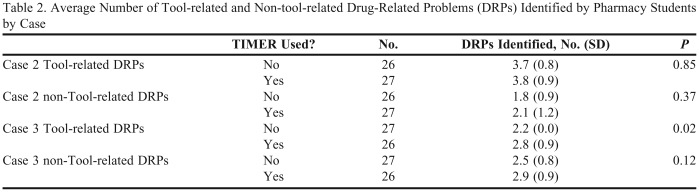

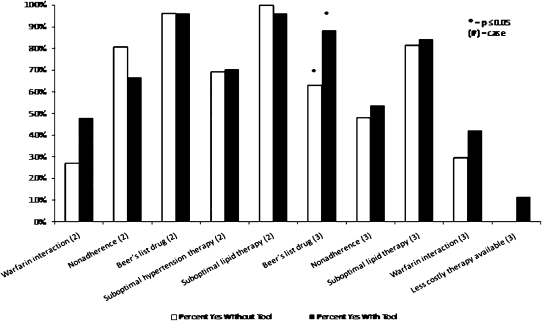

The average number of tool-related DRPs identified by the pharmacy students was 3.30 ± 1.05 using TIMER and 2.96 ± 1.13 not using TIMER (p = 0.11). There was no significant difference in the number of DRPs identified by laboratory section (p = 0.31). The overall 2-way ANOVA model predicting tool-related DRPs using TIMER and case was significant (p < 0.001). Case was significant (p < 0.001), but use of TIMER (p = 0.07) and the interaction were not significant (p = 0.12). When the effect of TIMER for each case was examined separately, the number of tool-related DRPs identified was significantly different for case 2 (p < 0.001, Table 2). Finally, the effect of TIMER on each tool-related DRP was examined. Only the DRP involving Beers’ list medications in case 2 showed a significant difference with use of TIMER (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Average Number of Tool-related and Non-tool-related Drug-Related Problems (DRPs) Identified by Pharmacy Students by Case

Abbreviations: TIMER = Tool to Improve Medication in Elderly via Review

Figure 2.

Student Pharmacists’ Identification of Individual Tool-Related DRPs by Use of TIMER (Tool to Improve Medications in the Elderly via Review)

DISCUSSION

In this randomized study, practicing pharmacists who used TIMER were able to identify more DRPs than practicing pharmacists given the same patient case but not TIMER. TIMER may be helpful to pharmacists because it provides a structured way of reviewing patients’ profile and medications. Importantly, it may identify DRPs that pharmacists otherwise would not have considered, such as Beer's List medications or new symptoms attributable to adverse drug events. TIMER also increased the number of non-tool-related DRPs identified by pharmacists. TIMER appeared to increase DRPs where pharmacists were less likely to identify problems, namely unintended adherence, warfarin interactions, and Beer's list drugs – although these were identified by less than 50% of pharmacists.

In part 2 of the study, pharmacy students identified nearly half of the tool-related DRPs in the patient cases without using TIMER. This may have occurred because students were given the case to complete at their laboratory workstations where they had a vast number of reference texts and online resources available to them. Students also had uninterrupted time in class to complete the cases. However, pharmacy students appeared less likely to identify warfarin interactions, nonadherence, and less costly therapy when TIMER was not used.

In the analysis for pharmacy students, the use of TIMER was not significant, but analysis by case indicated that TIMER increased the number of DRPs identified in case 2. The differences in the effects of TIMER on the 2 cases were probably due to the differences in the authors of the cases. Although the authors of each case reviewed both cases to ensure they contained similar numbers and types of DRPs, the author of case 1 has been an instructor for 12 years and had written cases for examinations as well as laboratory activities, while the author of case 2 had been an instructor for 1 year. The author having less experience writing cases may have made the DRPs in the first case “easier” for students to find, and having 2 different authors write the cases may be a limitation of this study. Yet, given that each case had a randomized control group for comparison strengthens the findings.

In 2 of the 3 patient cases used in this study, the number of DRPs identified by subjects increased. The fact that 3 different cases were used in this study increases the generalizability of the findings because findings are not limited to 1 set of drug-related problems or 1 type of patient care. TIMER may be more useful in some patients’ cases than others, as indicated by the results from pharmacy students. There was no single DRP that seemed more easily identifiable using TIMER.

The content validity of TIMER was established by experts who practice in geriatrics or family medicine. TIMER could be improved by including other DRPs typically identified by pharmacists such as high/low dose, ensuring an existing indication for all medications, and considering whether all indications are treated. However, we sought to include DRPs beyond those traditionally used by pharmacists. There are a number of companies that have created MTM plans or systems that prompt pharmacists when a DRP or problem is detected. These programs prompt pharmacists when an MTM service needs to be performed for a specific reason.1,2 Typically, these prompts are generated from prescription claims analyses, and we assert that pharmacists need to look at the entire patient when performing MTM. This reasoning was critical to the inclusion of a symptomology assessment in TIMER. It guides pharmacists through a broader review of patients and may serve as an added tool to any of these programs.

In order to use TIMER in practice, pharmacists may require training. We did not provide any training to participants in this study. Training could consist of how to read TIMER, how to apply it to individual patients, and how to examine each patient differently while using it. This might consist of a 30-minute session with an investigator, or a training program in print or online. TIMER also requires regular updates to reflect new guidelines, medications, and evidence.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. Although the cases used were representative of typical cases seen in practice, TIMER has not been tested with actual patients. Recommendations made by pharmacists or pharmacy students were not included, and these are important in resolving DRPs. Also, how TIMER may affect the efficiency of providing an MTM service was not tested. Additionally, 3 different case writers were used, but cases 2 and 3 were based on case 1 and the latter 2 cases were each reviewed by 2 of the investigators. Finally, this study involved pharmacy students from one University and innovative community pharmacists from the upper Midwest and West, thereby limiting its generalizability.

CONCLUSION

TIMER was effective in increasing the number of tool-related DRPs found by pharmacists and by pharmacy students in hypothetical patient cases. TIMER may help pharmacists provide required MTM services for older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was conducted with a grant from the University of Iowa Older Adults CERT (Centers for Education & Research on Therapeutics) that is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1 U18 HS016094-01) led by Dr. Elizabeth A. Chrischilles.

At the time of this study, Drs. Lee and Schwemm were fourth- and third-year pharmacy students, respectively, at the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Medicare Part D Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Programs 2008 FACT SHEET. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/MTMFactSheet.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2009.

- 2. Outcomes Pharmaceutical Health Care, http://www.getoutcomes.com/aspx/Pharmacists/currentmtmopportunities.aspx, accessed 14 January 2009.

- 3. Helping community pharmacies thrive. Mirixa, Reston, Va. http://www.mirixa.com/pharmacies.aspx. Accessed April 30, 2009.

- 4.McGivney MS, Meyer SM, Duncan-Hewitt W, Hall DL, Goode JV, Smith RB. Medication therapy management: its relationship to patient counseling, disease management, and pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47:620–8. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2007.06129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen RA, Roth MT, Brouwer ES, Herndon S, Christensen DB. Medication therapy management services in North Carolina community pharmacies: current practice patterns and projected demand. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2006;46:700–6. doi: 10.1331/1544-3191.46.6.700.hansen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doucette WR, McDonough RP, Klepser D, McCarthy R. Comprehensive medication therapy management: identifying and resolving drug-related issues in a community pharmacy. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1104–11. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(05)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currie JD, Chrischilles EA, Kuehl AK, Buser RA. Effect of a training program on community pharmacists' detection of and intervention in drug-related problems. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1997;37:182–91. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassam R, Farris KB, Burback L, Volume CI, Cox CE, Cave A. Pharmaceutical care research and education project: pharmacists' interventions. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2001;41:401–10. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenback KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296:2858–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan SD, Kreling DH, Hazlet TK. Noncompliance with medication regimens and subsequent hospitalizations: a literature analysis and cost of hospitalization estimate. J Res Pharm Econ. 1990:219–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roughhead EE, Gilbert AL, Primrose JG, et al. Drug-related hospital admission: a review of the Australian studies published 1988-96. Med J Australia. 1998;168:405–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb138996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caterino JM, Emond JA, Carmargo CA. Inappropriate medication administration to the acutely ill elderly: a nationwide emergency department study, 1992-2000. J Am Geriatric Soc. 2004;52:1847–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis LH, Ostbye T, Sendersky V, et al. Inappropriate prescribing for elderly Americans in a large outpatient population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1621–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan C, Correa-de-Araujo R, Bierman A, et al. Suboptimal prescribing in elderly outpatients: potentially harmful drug-drug and drug-disease combinations. J Am Geriatric Soc. 2005;53:262–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borum J, et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1556–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older people in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003;289:1107–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higashi T, Shekelle PG, Solomon DH, et al. The quality of pharmacologic care for vulnerable older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;104:714–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-9-200405040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raffel OC, White HD. Drug insight: Statin use in the elderly. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3:318–28. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kvan E, Pettersen KI, Landmark K, Reikvam A. INPHARM study investigators. Treatment with statins after acute myocardial infarction in patients >or=80 years: underuse despite general acceptance of drug therapy for secondary prevention. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:261–7. doi: 10.1002/pds.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran CT, Laupacis A, Mamdani MM, Tu JV. Effect of age on the use of evidence-based therapies for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004;148:834–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:755–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher J, Reuben DB, Beck JC. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1825–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. New Facts About Pharmacologic Management in Older Adults, Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders, Pfizer Inc. Available at: http://www.rand.org/health/projects/acove/acove3/. Accessed May 7, 2009.

- 25.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzgerald LS, Hanlon JT, Shelton PS, et al. Reliability of a modified medication appropriateness index in ambulatory older persons. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:543–8. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassam R, Martin LG, Farris KB. Reliability of a modified medication appropriateness index in community pharmacies. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:40–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1c077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Smet PA, Denneboom W, Kramers C, Grol R. A composite screening tool for medication reviews of outpatients: general issues with specific examples. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:733–60. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dugan BD. Enhancing community pharmacy through advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70:21. doi: 10.5688/aj700121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urmie JM, Farris KB, Herbert KE. Pharmacy students' knowledge of the Medicare drug benefit and intention to provide Medicare medication therapy management services. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71:41. doi: 10.5688/aj710341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cameron KA. Comment on medication management models and other pharmacist interventions: implications for policy and practice. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2005;24:73–85. doi: 10.1300/J027v24n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Pharmacists Association. National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication Therapy Management in community pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service (version 1.0) J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005;45:573–9. doi: 10.1331/1544345055001256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]