Abstract

Directed evolution can generate a remarkable range of new enzyme properties. Alternate substrate specificities and reaction selectivities are readily accessible in enzymes from families that are naturally functionally diverse. Activities on new substrates can be obtained by improving variants with broadened specificities or by step-wise evolution through a sequence of more and more challenging substrates. Evolution of highly specific enzymes has been demonstrated, even with positive selection alone. It is apparent that many solutions exist for any given problem, and there are often many paths that lead uphill, one step at a time.

Introduction

Directed evolution is now well established as highly effective for protein engineering and optimization. Directed evolution entails accumulation of beneficial mutations in iterations of mutagenesis and screening or selection; it can be thought of as an uphill climb on a `fitness landscape', a multidimensional plot of fitness versus sequence. Fitness in a directed evolution experiment - how the protein performs the target function under the desired conditions - is defined by the experimenter, who also controls the relationship between fitness and reproduction. There are an enormous number of ways to mutate any given protein: for a 300-amino acid protein there are 5700 possible single amino acid substitutions and already 32,381,700 ways to make just two substitutions. The number of ways to make four substitutions is bigger than the US national debt, a very large number indeed. Because most mutational paths lead downhill and eventually to unfolded, useless proteins (there are far many more ways to make a useless protein than a useful one), the challenge lies in identifying an efficient path to the desired function.

With accumulating evolutionary enzyme engineering experience and particularly owing to studies in which the results of evolution, both natural and directed, have been dissected to identify the adaptive mutations and possible pathways of their accumulation [1-3,4•], it is becoming clear that (1) multiple solutions are often accessible for any given functional problem and (2) there is usually a pathway whereby the target property can be acquired in a series of single, individually beneficial amino acid mutations. Whereas negative epistatic effects (in which a combination of mutations is beneficial although at least one individual mutation is not) are pervasive in natural evolution [5,6], there is little evidence that such effects have played a major role in facilitating directed evolution. The vast majority of evolutionary engineering studies over the past ten years involve simple uphill walks, one step at a time. Recent work reviewed here shows that the simple uphill walk can go to quite interesting places!

Functional characterization of intermediates along evolutionary pathways has also highlighted how the acquisition of activity on new substrates often proceeds through enzymes that accept a much broader range of substrates [7]. Studies also continue to show that subsequent re-specialization of these `generalists' is possible. Finally, it is increasingly clear that the natural history of an enzyme is a good indicator of its evolvability [8]: enzymes from large families exhibiting diverse functions or broad substrate ranges are easy to evolve in the laboratory. The same mechanisms leading to their natural functional diversity facilitate the acquisition of new functions in the laboratory.

There are many ways to create sequence diversity, and this is an important part of the search strategy for molecular optimization. The goal in choosing a mutagenesis strategy is to minimize the screening requirement and increase the chances of finding beneficial mutations [9•]. There is no single `best'mutagenesis method. Because there are many paths to a given goal, multiple methods will work (although some are far more efficient than others). Methods for generating diversity and advances in selection and screening methods for enzymes have been reviewed recently [10-12] and are also covered elsewhere in this issue. Here we will limit our discussion to a few selected topics where recent literature has made significant advances in our understanding and practice of directed enzyme evolution.

Promiscuous intermediates and the importance of natural history

Evolution has created numerous specialized enzymes that function in living cells to catalyze the chemical reactions of life. Their specificity is tuned so that they generally do not tread on each other's toes. But that does not mean their specificity is absolute: a recurring observation has been that many enzymes have weak activity on non-native substrates and that directed evolution can amplify these weak activities. When the desired activity is not measurable in the wild-type enzyme, it may be possible to find it in close variants that have been evolved for activity on other substrates [13] or even in enzymes that have been evolved neutrally, accumulating mutations that do not significantly damage the native activity [14,15]. These mutated enzymes tend to exhibit broader functional ranges, possibly through degradation of specific interactions with the natural substrate and conferring the ability to bind multiple substrates [8].

Experience indicates that changing the activities of enzymes for which there already exists functional diversity in nature is easier than for enzymes that tend to have very specific functions across many species. Diversifying function is `easy' if there are multiple single-amino acid substitutions that do it. Enzymes involved in secondary metabolite formation, for example, are often quite promiscuous in their substrate specificities and reaction selectivities [16]. They are also highly evolvable: single amino acid substitutions in carotenoid biosynthetic enzymes - synthases, desaturases, cyclases, and oxygenases - alter both substrate specificity and reaction selectivity to produce a variety of novel carotenoids [17]. O'Maille et al.[18••] analyzed the catalytic landscape between a sesquiterpene synthase and its functionally orthogonal homolog (75% identity) by investigating a large fraction of the 512 possible variants having different subsets of the nine amino acid changes known to inter-convert reaction selectivity (one synthase produces 5-epiaristolochene from farnesyl diphosphate, while the other produces premnaspirodiene). About half of the sesquiterpene synthase variants catalyzed the formation of both parental synthase products as well as several other terpenes, some produced naturally by related synthases. Alternate selectivities were accessible from these intermediate enzymes with as little as a single amino acid change.

Although amino acid residues that alter substrate selectivity or specificity are often located in the active site/substrate binding pocket, it is also often observed that mutations conferring changes in these properties are not. Even distant mutations can significantly affect catalysis by slightly altering the geometry, electrostatic properties, or dynamics of amino acids in the active site, which influence the course of a reaction, particularly after a high-energy intermediate is formed. For example, only two of the nine synthase amino acid residues investigated in the sesquiterpene synthases were in the active site, with the remainder scattered throughout the enzyme. Changing just the two in the active site resulted in the formation of 4-epi-eremophilene, a terpene not normally produced in nature, while changing two non-active site residues incrementally converted the synthase from a mainly 5-epi-aristolochene producer to one producing mainly premnaspirodiene. Umeno et al.[17] called this type of evolvable chemistry `pachinko chemistry', referring to the popular Japanese game in which the fate of a raised metal ball depends on the precise interactions it has with small metal pins as it falls down a board.

Other examples of evolvable enzymes include cytochrome P450s [19,20], glutathione transferases [21], enzymes having the common (β/α)8 barrel scaffold [22,23], and members of α/β hydrolase-fold families such as esterases and lipases [4•, 24, 25]. All these families exhibit wide functional diversity in nature. We have observed anecdotally that obtaining functional diversity - for example, activity on many new substrates - tends to be more difficult when the targeted enzyme does not have functionally diverse natural homologs. It is possible that such enzymes have more specific contacts with their substrates that preclude functional evolution through single beneficial mutations.

Evolving novel activity

Not long ago engineering a novel activity was considered to be a major challenge for directed evolution. Whereas engineering catalysts for new reactions is still extremely challenging, obtaining activity on a new substrate is far less so. If an enzyme does not already exhibit a desired activity, the difficulty of engineering that activity depends on how many amino acid substitutions are required to reach it. If even two simultaneous amino acid substitutions are needed to generate measurable activity, and those mutations are made randomly, the screening requirement is already very high. The complexity grows exponentially with the number of required changes. Strategies to overcome this exponential explosion include (1) converting the big challenge into a series of smaller ones by incrementally changing the selection pressure to achieve the desired activity (analogous to increasing temperature slightly in each generation to find highly thermostable enzymes), for example, by choosing intermediate target substrates that individually represent small hurdles but lead to the desired activity [26], and (2) creating a `generalist' enzyme, with broader specificity that includes weak activity toward the desired substrate, and then improving the activity of that generalist. Directing multiple simultaneous mutations to a smaller set of amino acid positions in a hybrid `rational'/evolutionary engineering approach is also possible [9•,27-30], but of course works only if the desired function is encoded by changes in the targeted sites.

The incremental challenge approach to obtaining a new activity was used by Fasan et al.[31••], who converted a cytochrome P450 fatty acid hydroxylase into a highly efficient propane hydroxylase, an activity absent in the native enzyme. They first improved the existing weak activity on octane until there was sufficient side activity on propane to allow screening directly on a surrogate of the smaller alkane. The propane hydroxylase they obtained has sufficient side activity on ethane to allow screening for hydroxylation of that substrate.

Early steps in directed evolution for activity on a non-native substrate often create `generalists' that are active on a much broader range of substrates. These have been used in a more serendipitous approach to obtaining new activities. For example, a broad-range, stereoselective D-amino acid dehydrogenase was generated from mesodiaminopimelate D-hydrogenase [32] with a first round of directed evolution to identify variants that could accept substrates similar to the native substrate, meso-diaminopimelic acid. One variant had activity on D-lysine, and additional rounds of evolution further broadened its substrate range to include straight-chain aliphatic and aromatic amino acids. In another example, galactose oxidase was initially evolved to increase its activity on D-glucose; one variant had a broader substrate range that included 1-phenylethanol. Further directed evolution improved its activity on 1-phenylethanol as well as other secondary alcohols [33].

New activities can also arise during `neutral drifts', in which mutations that do not abolish the native activity are accumulated in multiple rounds of high-error-rate mutagenesis and screening [15,34,35]. Similarly, the large number of mutations made by recombination of homologous glutathione transferases [21] and cytochrome P450s [36] - which can be thought of as a type of intense neutral drift - led to the emergence of activities not observed in the parent enzymes.

Enzyme engineers also want to catalyze new reactions, but these are harder to obtain by directed evolution. This is where rational design can provide a crucial boost by assembling at least the rudiments of an active site. Recent enzymes designed de novo using computational methods show both the promise and limitations of the approach (and of our understanding of enzyme function and ability to translate that into a design) [37•, 38]. Reactions for which there are no known counterparts in nature become accessible when the designed protein binds the transition state with higher affinity than the substrates or products. Unfortunately, transition state binding is just one piece of the catalysis puzzle, and the resulting catalysts are not particularly impressive, at least compared to most enzymes. Directed evolution, however, can take over where rational design necessarily leaves off: with the fine-tuning. Seven rounds of random mutagenesis, recombination, and screening improved the kcat/Km of a designed Kemp elimination catalyst >200-fold [37•]. The eight accumulated amino acid substitutions occurred at positions adjacent to the designed residues as well as farther from the active site.

Evolving specific enzymes

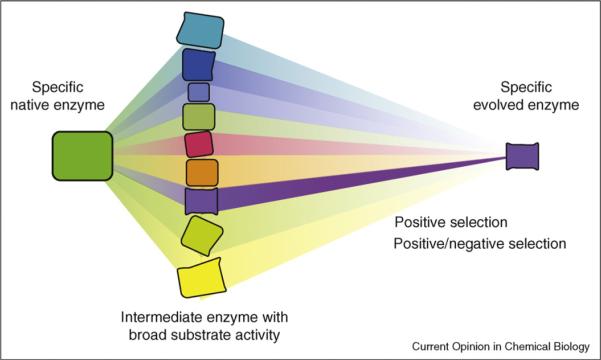

On rare occasions an enzyme with high specificity for a new substrate can be generated with a single amino acid substitution [39]. Activity on a new substrate, however, is usually achieved by broadening the substrate range (Figure 1), which indicates that these `generalist' enzymes are the most accessible, and frequent, solutions. In fact, there are usually many ways to obtain low activity on a new substrate [9•, 34, 36, 40•, 41]. If a substrate-specific enzyme is required, it may be possible to eliminate variants that maintain activity on the native or another undesired substrate using negative selection. Further mutagenesis may also be required to obtain the desired specificity, with positive selection to improve the desired activity and negative selection to remove the undesired one(s). Recent examples include highly active and selective endopeptidases generated using positive and negative selection with a fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) screen [29,30] and a D-xylose-specific xylose reductase engineered using positive and negative selection for growth or inhibition on the substrates [42].

Figure 1.

Directed evolution of enzyme activity on a new substrate often proceeds via a `generalist' that shows weak activity on multiple substrates. Evolution of a specific enzyme from a generalist can be done with positive selection for the new activity and negative selection to remove those variants having the undesired activity. Specificity can also be achieved by positive selection alone, if the solution to high activity on one substrate precludes high activity on others.

Specificity can also come as a side result of continued pressure for higher activity on the new substrate when interactions with the new substrate interfere with recognition of the old. Fasan et al. evolved their highly active propane monooxygenase with positive selection alone over multiple rounds of mutagenesis and screening for activity on propane [31••]. The substrate range of this enzyme turned out to be very narrow and no longer included the native C12-C20 fatty acid substrates, or even octane [43•]. When new activities are obtained in early generations of directed evolution via a generalist enzyme, these new activities are usually well below that of the native enzyme on its preferred substrates. Further evolution to enhance one activity comes at the cost of the others when the substrates differ structurally and chemically and therefore interact with the enzyme in mutually incompatible ways. The ease of re-specialization obviously depends on how easily the enzyme can recognize those differences.

Changing or increasing enzyme enantioselectivity is important for creating biocatalysts for synthetic organic chemistry [44]. Because the solution to this problem is reconfiguring the active site to accept (or produce) only one enantiomer, it was anticipated to be difficult to engineer in enzymes, probably requiring multiple simultaneous mutations. To evolve an enantioselective lipase, Reetz et al.[4•] initially used random mutagenesis with a high error rate and then saturation mutagenesis of residues in the active site. The best enantioselective lipase from that set contained six amino acid mutations. Computational analysis predicted that only two of these were necessary, and the double variant in fact had greater enantioselectivity than the variant with all six mutations. Because both mutations contributed positively to the new phenotype (no negative epistasis), an uphill walk could have found the double variant, particularly if beneficial mutations were recombined (e.g. by shuffling) or if several improved mutants were evolved in parallel after the first round.

Directed evolution usually goes through single amino acid improvements

Analysis of the directed evolution literature shows that a wide range of problems can be solved by uphill walks involving single amino acid changes. Often, single mutations are responsible for the functional change, even when multiple mutations are made [45]. Or, when multiple beneficial mutations are found, they all contribute and could have been found separately, as in the enantioselectivity example discussed above. Analysis of reconstructed evolutionary intermediates supports these observations by demonstrating that multiple pathways of small incremental improvements exist [1,2].

Not surprisingly, then, a highly effective and efficient directed evolution strategy is to gradually accumulate single beneficial mutations, either sequentially or by recombination, while applying (often increasing) selection pressure. Low error-rate random mutagenesis by error-prone PCR is very simple to implement, but only accesses a limited set of (mostly conservative) amino acid changes. Other mutagenesis methods, including saturation mutagenesis, can effectively generate additional amino acid possibilities in targeted residues. Such a walk does not require construction and screening of very large libraries: a few thousand clones can cover much of the single-mutant possibilities in each generation. With the reduced screening load comes the possibility of using screens that are higher in quality and more likely to accurately interrogate the desired properties.

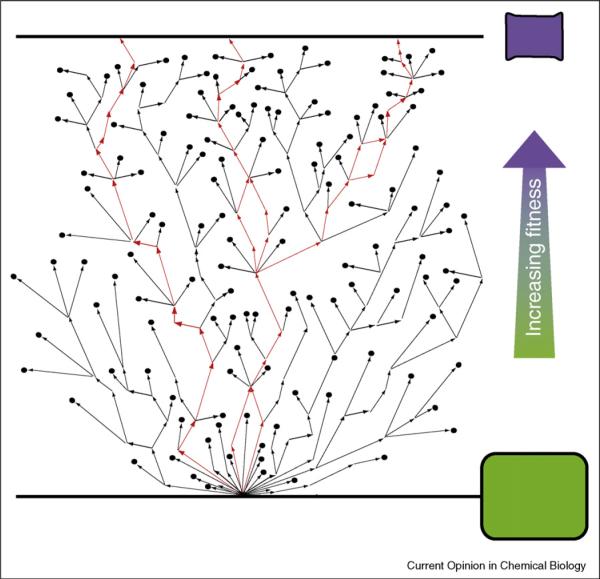

An uphill walk via single beneficial mutations works only if (1) intermediates exist along the path from the starting point to the desired enzyme that incrementally improve the desired properties, and (2) the path chosen in each generation does not lead to a dead end (Figure 2). There are effective ways to circumvent apparent dead ends, including incorporation of stabilizing mutations that allow the accumulation of new functional, but destabilizing mutations [31••, 46]. Natural evolution apparently uses this route, where a `global suppressor' mutation that is functionally neutral or even slightly deleterious can make up for the effects of an adaptive mutation that would otherwise destabilize and destroy the protein [34]. Another way to circumvent dead ends is to evolve multiple routes in parallel. Multiple routes can be explored simultaneously by maintaining populations in each round; the screening requirement scales linearly with the population size. Coupled mutations are not discovered by this route because the low error-rate in the mutagenesis step simply does not make them. But, because there are likely to be multiple solutions (sequences) that satisfy a fitness challenge, and because there are many paths to those solutions, negative epistatic paths, which definitely exist [47], can simply be bypassed.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical evolutionary trajectories following an uphill walk to the desired fitness. Single amino acid substitutions corresponding to an increase in fitness are indicated by an arrow. (The much larger numbers of neutral and deleterious mutations are not shown.) More than one sequence can have the desired fitness, and multiple paths lead to those sequences. Restricting the number of amino acid positions that are varied or the number of different amino acids sampled at each position, however, may lead to dead ends (filled circles). A dead end is also reached when the protein is no longer stable enough to accept new mutations. Further improvements from these dead ends may become accessible once the protein is stabilized.

When the mutation rate is high, beneficial mutations are quickly masked by the much more frequent deleterious ones. Low error rates - 1-2 amino acid substitutions per gene - are therefore preferred if the entire gene is mutated. Statistical methods to identify beneficial mutations in variants containing multiple mutations have been described [48,49] and allow simultaneous examination of substitutions at more positions. But, to reliably identify beneficial ones, one must examine many mutation combinations [49] or make tailored sets of sequences where mutations are represented approximately an equal number of times (to avoid statistical biases) [48].

An uphill walk by iterative saturation mutagenesis at a small number of targeted residues is feasible if the desired property is encoded by changes at the chosen sites [50]. Saturation mutagenesis of course explores a wider range of amino acid choices, but at a much smaller range of positions. Simultaneous saturation mutagenesis at more than one site has the benefit of potentially identifying mutations that only work in concert. As Reetz argues [9•], an efficient directed evolution strategy achieves the desired function with the least amount of work. And sometimes we even know enough about that function to be able to choose the sites to target [29,30].

The challenge of directing evolution

Even with high-quality mutant libraries and screening, not all bad enzymes can become good ones via a simple uphill walk—that is, not every poor enzyme lies at the base of a fitness peak. Some problems are more difficult, and coupled mutations might be necessary for the desired functional changes. Beneficial mutations are rare, but combinations of beneficial mutations that only work together are even rarer. While making targeted libraries [9•] may help, it is not clear that we know how to choose the amino acids to target. Enzymes have been found to populate an ensemble of conformational states, and each can contribute differently to catalysis if the active site residues are perturbed [51]. It is likely that not all protein folds are ideal for catalyzing desired reactions. Some starting points might require major changes (perhaps even to the protein architecture) in order to improve catalysis, and these changes are not accessible by directed evolution.

Acknowledgements

CAT was supported by Ruth M Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32 GM076964 and NIH grant R01 GM074712-01A1. We also acknowledge support from the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies, the Jacobs Institute for Molecular Medicine, and the Department of Energy.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest published within the period of review have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Weinreich DM, Delaney NF, Depristo MA, Hartl DL. Darwinian evolution can follow only very few mutational paths to fitter proteins. Science. 2006;312:111–114. doi: 10.1126/science.1123539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poelwijk FJ, Kiviet DJ, Weinreich DM, Tans SJ. Empirical fitness landscapes reveal accessible evolutionary paths. Nature. 2007;445:383–386. doi: 10.1038/nature05451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poelwijk FJ, Kiviet DJ, Tans SJ. Evolutionary potential of a duplicated repressor-operator pair: simulating pathways using mutation data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e58. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4•.Reetz MT, Puls M, Carballeira JD, Vogel A, Jaeger KE, Eggert T, Thiel W, Bocola M, Otte N. Learning from directed evolution: further lessons from theoretical investigations into cooperative mutations in lipase enantioselectivity. Chembiochem. 2007;8:106–112. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors reexamine a variant containing six mutations identified in an earlier study. They confirmed previous computational predictions experimentally and demonstrated that only two substitutions contributed to the change in enantioselectivity

- 5.Yokoyama S, Tada T, Zhang H, Britt L. Elucidation of phenotypic adaptations: molecular analyses of dim-light vision proteins in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13480–13485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802426105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinreich DM, Watson RA, Chao L. Perspective: sign epistasis and genetic constraint on evolutionary trajectories. Evolution. 2005;59:1165–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khersonsky O, Roodveldt C, Tawfik DS. Enzyme promiscuity: evolutionary and mechanistic aspects. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Loughlin TL, Patrick WM, Matsumura I. Natural history as a predictor of protein evolvability. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2006;19:439–442. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9•.Reetz MT, Kahakeaw D, Lohmer R. Addressing the numbers problem in directed evolution. Chembiochem. 2008;9:1797–1804. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper compares libraries constructed from NNK codons (32 codons/20 aa) to libraries having reduced codon degeneracy composed of NDT codons (12 codons/12 aa). The reduced library complexity yields a higher frequency of positive hits

- 10.Jackel C, Kast P, Hilvert D. Protein design by directed evolution. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:153–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bershtein S, Tawfik DS. Advances in laboratory evolution of enzymes. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong TS, Roccatano D, Schwaneberg U. Steering directed protein evolution: strategies to manage combinatorial complexity of mutant libraries. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2645–2659. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landwehr M, Hochrein L, Otey CR, Kasrayan A, Backvall JE, Arnold FH. Enantioselective alpha-hydroxylation of 2-arylacetic acid derivatives and buspirone catalyzed by engineered cytochrome P450 BM-3. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6058–6059. doi: 10.1021/ja061261x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloom JD, Romero PA, Lu Z, Arnold FH. Neutral genetic drift can alter promiscuous protein functions, potentially aiding functional evolution. Biol Direct. 2007;2:17. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta RD, Tawfik DS. Directed enzyme evolution via small and effective neutral drift libraries. Nat Methods. 2008;5:939–942. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischbach MA, Clardy J. One pathway, many products. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:353–355. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0707-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umeno D, Tobias AV, Arnold FH. Diversifying carotenoid biosynthetic pathways by directed evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:51–78. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.51-78.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18••.O'Maille PE, Malone A, Dellas N, Andes Hess B, Jr, Smentek L, Sheehan I, Greenhagen BT, Chappell J, Manning G, Noel JP. Quantitative exploration of the catalytic landscape separating divergent plant sesquiterpene synthases. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:617–623. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper examines how nine naturally occurring amino acid substitutions in a pair of synthases affect the product spectrum. The authors analyze the product distributions of 418 out of the 512 possible variants containing a subset of these mutations. Quantitative comparisons indicate context dependence of mutations. Single amino acid substitutions can significantly alter the product distribution, demonstrating the evolvable nature of these secondary metabolic pathway enzymes

- 19.Trefzer A, Jungmann V, Molnar I, Botejue A, Buckel D, Frey G, Hill DS, Jorg M, Ligon JM, et al. Biocatalytic conversion of avermectin to 4″-oxo-avermectin: Improvement of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase specificity by directed evolution. Appl Env Microbiol. 2007;73:4317–4325. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02676-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Vugt-Lussenburg BMA, Stjernschantz E, Lastdrager J, Oostenbrink C, Vermeulen NPE, Commandeur JNM. Identification of critical residues in novel drug metabolizing mutants of cytochrome P450BM3 using random mutagenesis. J Med Chem. 2007;50:455–461. doi: 10.1021/jm0609061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtovic S, Moden O, Shokeer A, Mannervik B. Structural determinants of glutathione transferases with azathioprine activity identified by DNA shuffling of alpha class members. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:1365–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damian-Almazo JY, Moreno A, Lopez-Munguia A, Soberon X, Gonzalez-Munoz F, Saab-Rincon G. Enhancement of the alcoholytic activity of alpha-amylase AmyA from Thermotoga maritima MSB8 (DSM 3109) by site-directed mutagenesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5168–5177. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00121-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterner R, Hocker B. Catalytic versatility, stability, and evolution of the (betaalpha)8-barrel enzyme fold. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4038–4055. doi: 10.1021/cr030191z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Hassler M, Bugg TD. Catalytic promiscuity in the alpha/beta-hydrolase superfamily: hydroxamic acid formation, C-C bond formation, ester and thioester hydrolysis in the C-C hydrolase family. Chembiochem. 2008;9:71–76. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartsch S, Kourist R, Bornscheuer UT. Complete inversion of enantioselectivity towards acetylated tertiary alcohols by a double mutant of a Bacillus subtilis esterase. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1508–1511. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Z, Zhao H. Rapid creation of a novel protein function by in vitro coevolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reetz MT, Wang LW, Bocola M. Directed evolution of enantioselective enzymes: iterative cycles of CASTing for probing protein-sequence space. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1236–1241. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman A, Tawfik DS. Incorporating synthetic oligonucleotides via gene reassembly (ISOR): a versatile tool for generating targeted libraries. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2007;20:219–226. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varadarajan N, Georgiou G, Iverson BL. An engineered protease that cleaves specifically after sulfated tyrosine. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:7861–7863. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varadarajan N, Rodriguez S, Hwang BY, Georgiou G, Iverson BL. Highly active and selective endopeptidases with programmed substrate specificities. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:290–294. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Fasan R, Chen MM, Crook NC, Arnold FH. Engineered alkanehydroxylating cytochrome P450(BM3) exhibiting nativelike catalytic properties. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:8414–8418. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This works demonstrates the progressive challenge approach to evolving an enzyme for a substrate not accepted by the wild-type enzyme. Furthermore, positive selection for activity on propane was sufficient to generate a highly specific enzyme. Unlike most engineered cytochrome P450s, utilization of NADPH in the evolved enzyme is fully coupled to substrate oxidation, a result of evolutionary optimization of all three domains. The properties of the intermediates along the evolutionary trajectory are described in reference [43]

- 32.Vedha-Peters K, Gunawardana M, Rozzell JD, Novick SJ. Creation of a broad-range and highly stereoselective D-amino acid dehydrogenase for the one-step synthesis of D-amino acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10923–10929. doi: 10.1021/ja0603960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Escalettes F, Turner NJ. Directed evolution of galactose oxidase: generation of enantioselective secondary alcohol oxidases. Chembiochem. 2008;9:857–860. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bershtein S, Goldin K, Tawfik DS. Intense neutral drifts yield robust and evolvable consensus proteins. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:1029–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peisajovich SG, Tawfik DS. Protein engineers turned evolutionists. Nat Methods. 2007;4:991–994. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1207-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landwehr M, Carbone M, Otey CR, Li Y, Arnold FH. Diversification of catalytic function in a synthetic family of chimeric cytochrome P450s. Chem Biol. 2007;14:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Rothlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, DeChancie J, Betker J, Gallaher JL, Althoff EA, Zanghellini A, Dym O, et al. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature. 2008;453:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Computational enzyme design generated a `bad' enzyme that was made significantly `better' by multiple rounds of directed evolution, clearly demonstrating the power of combining these approaches. While a variety of scaffolds were tested for incorporation of this new activity, the (ba) barrel was the most effective and most evolvable

- 38.Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, Doyle L, Rothlisberger D, Zanghellini A, Gallaher JL, Betker JL, Tanaka F, Barbas CF, 3rd, et al. De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes. Science. 2008;319:1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1152692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saravanan M, Vasu K, Nagaraja V. Evolution of sequence specificity in a restriction endonuclease by a point mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10344–10347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804974105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Patrick WM, Matsumura I. A study in molecular contingency: Glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase is a promiscuous and evolvable phosphoribosylanthranilate isomerase. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors unexpectedly found that overexpressing glutamine phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase (PurF) rescued a tryptophan biosynthesis deficient strain (DtrpF) missing phosphoribosylanthranilate isomerase (PRAI) activity. The two enzymes are not homologous: PRAI is a (βα)8-barrel whereas PurF is neither a barrel nor related mechanistically. PurF, however, does bind phosphoribosylated substrates. Directed evolution improved the PRAI activity in PurF 25-fold, and the cells could survive with near wild-type fitness under the conditions tested, even though the enzyme was >107-fold less efficient than wild-type PRAI

- 41.Kurtovic S, Runarsdottir A, Emren LO, Larsson AK, Mannervik B. Multivariate-activity mining for molecular quasi-species in a glutathione transferase mutant library. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2007;20:243–256. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nair NU, Zhao H. Evolution in reverse: engineering a D-xylosespecific xylose reductase. Chembiochem. 2008;9:1213–1215. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Fasan R, Meharenna YT, Snow CD, Poulos TL, Arnold FH. Evolutionary history of a specialized P450 propane monooxygenase. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:1069–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Substrate specificity profiles of intermediates along the evolutionary path from wild-type P450 BM3 to the propane-hydroxylating variant (identified in reference [31••]) are compared on C2-C10 alkanes. Evolution for high activity on propane was achieved at the cost of activity on the native fattyacid substrates and even on slightly larger alkanes

- 44.Bolt A, Berry A, Nelson A. Directed evolution of aldolases for exploitation in synthetic organic chemistry. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carballeira JD, Krumlinde P, Bocola M, Vogel A, Reetz MT, Backvall JE. Directed evolution and axial chirality: optimization of the enantioselectivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipase towards the kinetic resolution of a racemic allene. Chem Commun (Camb) 2007:1913–1915. doi: 10.1039/b700849j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloom JD, Labthavikul ST, Otey CR, Arnold FH. Protein stability promotes evolvability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5869–5874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510098103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams GJ, Zhang C, Thorson JS. Expanding the promiscuity of a natural-product glycosyltransferase by directed evolution. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:657–662. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liao J, Warmuth MK, Govindarajan S, Ness JE, Wang RP, Gustafsson C, Minshull J. Engineering proteinase K using machine learning and synthetic genes. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox RJ, Davis SC, Mundorff EC, Newman LM, Gavrilovic V, Ma SK, Chung LM, Ching C, Tam S, Muley S, et al. Improving catalytic function by ProSAR-driven enzyme evolution. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:338–344. doi: 10.1038/nbt1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reetz MT, Carballeira JD. Iterative saturation mutagenesis (ISM) for rapid directed evolution of functional enzymes. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:891–903. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rissin DM, Gorris HH, Walt DR. Distinct and long-lived activity states of single enzyme molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5349–5353. doi: 10.1021/ja711414f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]