Abstract

The protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathway plays integral roles in the expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein that regulates steroid biosynthesis in steroidogenic cells. PKC can modulate the activity of cAMP/protein kinase A signaling involved in steroidogenesis; however, its mechanism remains obscure. In the present study, we demonstrate that activation of the PKC pathway, by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), was capable of potentiating dibutyryl cAMP [(Bu)2cAMP]-stimulated StAR expression, StAR phosphorylation, and progesterone synthesis in both mouse Leydig (MA-10) and granulosa (KK-1) tumor cells. The steroidogenic potential of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was linked with phosphorylation of ERK 1/2; however, inhibition of the latter demonstrated varying effects on steroidogenesis. Transcriptional activation of the StAR gene by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was influenced by several factors, its up-regulation being dependent on phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB). An oligonucleotide probe containing a CREB/activating transcription factor binding region in the StAR promoter was found to bind nuclear proteins in PMA and (Bu)2cAMP-treated MA-10 and KK-1 cells. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies revealed that the induction of phosphorylated CREB was tightly correlated with in vivo protein-DNA interactions and recruitment of CREB binding protein to the StAR promoter. Ectopic expression of CREB binding protein enhanced CREB-mediated transcription of the StAR gene, an event that was markedly repressed by the adenovirus E1A oncoprotein. Further studies demonstrated that the activation of StAR expression and steroid synthesis by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was associated with expression of the nuclear receptor Nur77, indicating its essential role in hormone-regulated steroidogenesis. Collectively, these findings provide insight into the mechanisms by which PKC modulates cAMP/protein kinase A responsiveness involved in regulating the steroidogenic response in mouse gonadal cells.

Protein kinase C modulates cAMP/PKA-mediated steroidogenesis and thus plays an important role in controlling gonadal development and function.

Steroid hormone biosynthesis is initiated on mobilization of cholesterol from cellular stores to the mitochondrial inner membrane, the site of the cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1). This process is recognized as the rate-limiting and regulated step in steroidogenesis and has been demonstrated to be mediated by the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein (1,2,3,4,5,6). The critical role of StAR in regulating steroidogenesis was further substantiated when patients suffering from lipoid congenital adrenal hyperplasia were determined to possess mutations in the StAR gene, leading to severe impairment of adrenal and gonadal steroid biosynthesis (7,8). Targeted disruption of the StAR gene in mice generates an essentially identical phenotype to that of lipoid congenital adrenal hyperplasia in humans (8,9). Regulation of steroidogenesis in gonadal cells involves a complex interaction of a diversity of hormones and multiple signaling pathways (5,10,11). Whereas the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway is unquestionably the major signaling cascade in the regulation of trophic hormone-stimulated StAR expression and steroidogenesis, several additional intracellular events have been demonstrated to play important roles in these processes (5,10,12). These studies documented the involvement of the ERK1/2 family of serine (Ser)/theronine (Thr) kinases in the regulation of the steroidogenic response (13,14,15,16,17). Nonetheless, a considerable amount of evidence indicates that trophic hormones can also activate the protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathway (12,17,18).

Studies on the role of the PKC pathway in steroidogenesis has produced conflicting results, describing positive, negative, or no influence in different steroidogenic cells (12,19,20). We have previously shown that the activation of PKC signaling markedly increases StAR expression but only moderately elevates progesterone synthesis in mouse Leydig cells due to the inability of PKC to phosphorylate and thus activate StAR (17,18). Whereas PKC is a weak inducer of steroid synthesis, it potentiates the gonadotropin and/or cAMP-mediated steroidogenic responsiveness and by doing so controls various gonadal/adrenal steroidogenic functions (5,12). However, the regulatory mechanisms of the PKC signaling cascade in the activation of LH/human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)/cAMP-mediated StAR expression and steroidogenesis remain obscure.

Transcriptional regulation of the StAR gene is mediated by multiple cis elements that bind directly or indirectly to DNA motifs located approximately 150 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site (21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28). Notably, whereas the StAR gene lacks a canonical cAMP response element, it is regulated by cAMP-dependent signaling, suggesting the involvement of alternate mechanisms in cAMP responsiveness. As such, several positive and negative elements were identified, and the combinatorial action of these factors in StAR gene expression has been demonstrated (23,24,25,27,28,29). One of the well-known downstream targets of the PKC and PKA pathways is the activation of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), which binds to cAMP response element or its variants after its phosphorylation at Ser133 and subsequently interacts with the CREB binding protein (CBP) (16,30,31,32). CBP and p300 (a functional homolog of CBP) are transcriptional coactivators, act as bridging proteins between the transcription factors and the general transcription machinery, and thus play critical roles in gene regulation (32). As well, the nuclear receptor Nur77 (also called nerve growth factor-induced clone B) has been shown to bind steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) recognition motifs in the StAR promoter and plays an important role in steroidogenesis (27,28,33,34). In light of these observations, the present investigation was designed to explore the mechanisms of PKC signaling in the modulation of cAMP-stimulated steroidogenesis using mouse Leydig and granulosa tumor cells.

Materials and Methods

Cells, transfections, and luciferase assays

MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells (35) were cultured in HEPES-buffered Waymouth MB/752 medium containing horse serum and antibiotics (28,36,37). KK-1 granulosa cells were derived from a tumor in a transgenic mouse expressing the Simian virus 40 (SV40) virus T antigen under the control of the murine inhibin α-subunit promoter (38) and were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing high glucose plus antibiotics (39,40).

MA-10 and KK-1 cells were transfected using FuGENE-6/-HD transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN), as described previously (37,41). Transfection efficiency was normalized by cotransfecting pRL-SV40, a plasmid that constitutively expresses renilla luciferase (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). Expression plasmids used for CREB, nonphosphorylatable mutant of CREB (CREB-M1, Ser133→Ala), CBP, E1A, Nur77, and dominant-negative (DN) Nur77 have been previously described (28,37,41).

Luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) using a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA), as described previously (28,37).

Construction of plasmids

The 5′-flanking −151/−1 bp region of the mouse StAR promoter was synthesized using a PCR based cloning strategy (36,37,42). Using the −151/−1 StAR-pGL3 as template, mutations in the specificity protein-1 (Sp1), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP), SF-1, CREB/ activator protein (AP)-1, GATA, sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP), and dosage-sensitive sex reversal-adrenal hypoplasia congenita critical region on the X chromosome, gene 1 (DAX-1) sites were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The sense strand of the oligonucleotide sequences used were (mutated bases underlined): Sp1, 5′-ACACAGTCTGCgaatTCCCACCTTGGCCAG-3′; C/EBP, 5′-GCACTGCAGGATGgtcgAcTCATTCCATCCTTG-3′; SF-1, 5′-CAATCATTCCAgCtgTGACCCTCTGCAC-3′; CREB/AP-1, 5′-CCTTGACCCTCTGCACAATagaTctTGACTTTTTTATCTC-3; GATA, 5′-GACTGATGACTTTTTccggaCAAGTGATGATGCACAG-3; SREBP, 5′-ACTTTTTTATCTCtcGaGATGATGCACAGCCTTCCAC-3′; and DAX-1, 5′-GCACAGCCTTgCggccGcAGCATTTAAGGC-3′. Specific mutations were tested by restriction endonuclease digestion using EcoRI (Sp1), SalI (C/EBP), PvuII (SF-1), BglII (CREB/AP-1), BspEI (GATA), XhoI (SREBP), and NotI (DAX-1). Mutations containing an XhoI and HindIII fragment were religated into the pGL3 vector. All plasmids were confirmed by automated sequencing on a PE Biosystem 310 genetic analyzer (ABI PRISM, PerkinElmer, Norwalk, CT).

Western blotting

Immunoblotting studies were carried out using total cellular protein (16,43). Briefly, equal amounts of protein (20–30 μg) were loaded onto either 10 or 6% SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto Immuno-Blot polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were probed with the specific antibodies (Abs) that recognize StAR (44), phosphorylated (P) StAR (Ser194) (16) that detects both PKA- and PKC-induced P-StAR, DAX-1 (45), SF-1 (46), ERK1/2, SREBP-1 (BD Biosciences/PharMingen, San Diego, CA), Sp1 (sc-59), C/EBPβ (sc-150), CBP (sc-7300), cFos (sc-52), cJun (sc-1694), GATA-4 (sc-9053), P-GATA-4 (Ser262, sc-32823) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), CREB, P-CREB (Ser133), P-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), P-C/EBPβ (Thr235), Nur77 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), CYP11A1 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and actin (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX). After processing of membranes with appropriate secondary Abs, immunodetection of proteins was determined with the chemiluminescence imaging Western lightning kit (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). The intensity of immunospecific bands was quantified using a computer-assisted image analyzer (Visage 2000; BioImage, Ann Arbor, MI).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was used for amplification of mouse StAR cDNA using the following primer pairs: StAR sense, 5′-GACCTTGAAAGGCTCAGGAAGAAC-3′, and StAR antisense, 5′-TAGCTGAAGATGGACAGACTTGC-3′ (16,42,47). The variation in RT-PCR efficiency was assessed by amplifying an L19 ribosomal protein gene using the primers, L19 sense, 5′-GAAATCGCCAATGCCAACTC-3′, and L19 antisense, 5′-TCTTAGACCTGCGAGCCTCA-3′. Reverse transcription and PCR were run sequentially in the same assay tube using 2-μg of total RNA, which included [α32P]dCTP (PerkinElmer) in the deoxynucleotide triphosphate mixture. The cDNAs generated were further amplified by PCR using the primer pairs listed above. The molecular sizes of StAR and L19 were determined on 1% agarose gels, which were then vacuum dried and the resulting signals were quantified (Visage 2000; BioImage).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were carried out using a kit (Upstate/Chemicon, Temecula, CA), under optimized conditions (28,37). Briefly, cells were incubated with formaldehyde (1%) for 10 min at 37 C to cross-link DNA and its associated proteins. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer and then sonicated for seven to nine cycles of 10-sec pulses using a Tekmar sonic disruptor (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The supernatant containing chromatin was cleared with protein A agarose/salmon sperm DNA 50% slurry for 30 min at 4 C with agitation. After centrifugation, the supernatant was immunoprecipitated with 4–5 μg of Abs specific to P-CREB (as above) and CBP (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) for 14 h at 4 C. The chromatin-antibody-protein A agarose complexes were subsequently washed with low salt, high salt, LiCl, and Tris/EDTA buffers, and protein-DNA complexes were eluted. NaCl (20 mm) was added to the eluates that were then incubated at 65 C for 4 h to reverse the formaldehyde cross-linking. The samples were treated with proteinase K for 1 h at 45 C, and DNA samples were used for PCR using [α32P]dCTP in the deoxynucleotide triphosphate mixture. PCR was performed with about 100 ng of DNA and the proximal StAR promoter primers (forward, 5′-CTGGTCCTCCCTTTACACAGTC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGCGCAGATCCAGTGCGCTGC-3′) (37,42). PCR products (170 bp) were determined on 2% agarose gels. Gels were vacuum dried, and the resulting signals were visualized and quantified (Visage 2000; BioImage).

EMSAs

EMSA experiments were performed using nuclear extracts (NE) obtained from MA-10 and KK-1 cells. The sense strands of the oligonucleotide sequences used were: −83/−67 bp, 5′-GGAATGACTGATGACTTTT-3′, and −83/−67 bp mutant (−83/−67M), 5′-GGAATAGATCTTGACTTTT-3′. The doubled-stranded oligonucleotide was end labeled with [α32P]dCTP using Klenow fill-in reaction, and DNA-protein binding assays were performed (28,37). Briefly, NE (12–15 μg) was incubated for 15 min at room temperature in a 20-μl reaction buffer before the addition of a 32P-labeled probe either alone or in the presence of unlabeled oligonucleotides. DNA-protein binding was then subjected to electrophoresis on 5% polyacrylamide gels, which were dried, and the resulting signals were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA using Statview (Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, CA) followed by Fisher’s protected least significant differences test. All experiments were repeated three to six times. Data presented are the mean ± se, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Role of the PKC pathway in the modulation of dibutyryl cAMP [(Bu)2cAMP]-mediated steroidogenesis

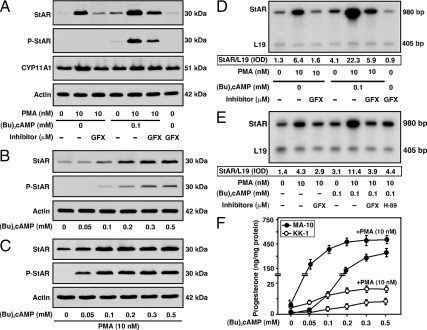

The mechanisms of PKC signaling in the activation of (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR expression and steroidogenesis was explored in gonadal cells. MA-10 cells treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 10 nm) demonstrated 7.6 ± 1.2- and 4.3 ± 0.7-fold increases in StAR protein expression and progesterone synthesis over untreated cells, respectively (Fig. 1A). P-StAR was undetectable in response to PMA. Cells pretreated with a PKC inhibitor, GF-109203X [GFX; 20 μm; (17,18)] markedly diminished (P < 0.01) PMA-induced StAR expression. A subthreshold dose of (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm) showed 3.4 ± 0.3- and 9.2 ± 1.5-fold increases in StAR expression and progesterone synthesis over respective basal values (Fig. 1, A and F). Addition of PMA to (Bu)2cAMP-treated cells synergistically enhanced StAR, P-StAR, and steroid levels. PMA also dose-dependently elevated (Bu)2cAMP-induced progesterone synthesis. Expression of the CYP11A1 protein was increased (P < 0.05) by PMA; however, its level was not further effected by cotreatment with (Bu)2cAMP. Qualitatively similar results were observed when StAR mRNA levels in response to PMA and (Bu)2cAMP were determined by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 1D). Alternatively, KK-1 cells treated with varying doses of (Bu)2cAMP (0.05–0.5 mm) demonstrated increases in StAR, P-StAR, and progesterone levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1, B, C, and F). Whereas PMA resulted in 3.2 ± 0.4- and 2.2 ± 0.3-fold increases in StAR protein and progesterone synthesis over respective basal, it enhanced (Bu)2cAMP-responsive StAR, P-StAR, and steroid levels in a dose-responsive fashion. PMA had lesser effects on the steroidogenic response with higher doses of (Bu)2cAMP (0.2–0.5 mm). RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that PMA, (Bu)2cAMP, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP resulted in approximately 3-, 2.2-, and 8-fold increases in StAR mRNA levels when compared with controls (Fig. 1E). The combined effect of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP on StAR mRNA expression was decreased (P < 0.05) by PKC (GFX) and PKA [H-89, 20 μm (17,42)] inhibitors. These findings demonstrate that PKC potentiates (Bu)2cAMP-induced StAR expression and steroidogenesis in mouse gonadal cells. Notably, PMA did not increase, but rather moderately decreased (P < 0.05), intracellular cAMP (basal, 0.67 ± 0.09; PMA, 0.48 ± 0.06 pmol per 30 min per 105 cells) and had no effect on hCG-induced cAMP levels (hCG, 4.12 ± 0.53; PMA plus hCG, 4.38 ± 0.62 pmol per 30 min per 105 cells) in KK-1 cells, patterns that were similar in MA-10 and other Leydig cells (data not shown and Refs. 19, 48).

Figure 1.

Role of PKC in the modulation of (Bu)2cAMP-stimulated StAR expression, P-StAR, and progesterone synthesis. MA-10 (A, D, and F) and KK-1 (B, C, E, and F) cells were pretreated without or with PKC (GFX, 20 μm) and PKA (H-89, 20 μm) inhibitors for 30 min and then treated with PMA (10 nm) in the absence or presence of either fixed (0.1 mm) or increasing amounts of (Bu)2cAMP (0.05–0.5 mm) for 6 h, as indicated. Representative immunoblots show StAR, P-StAR, and CYP11A1 levels in different treatment groups using 20–30 μg of total cellular protein. Total RNA isolated from the specific treatment groups was subjected to RT-PCR analysis for determining StAR mRNA expression, and representative autoradiograms are illustrated in D and E. Integrated OD (IOD) values of each band were quantified, normalized with the corresponding L19 bands, and presented as StAR/L19. Data shown in immunoblotting and RT-PCR analyses are representative of three to five independent experiments. Actin and L19 expression was used as loading controls in Western and RT-PCR analyses, respectively. Accumulation of progesterone in the media was determined and expressed as nanograms per milligram protein (F), which represent the mean ± se of four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

Effect of PMA on (Bu)2cAMP-mediated ERK1/2 signaling and its relevance to steroidogenesis

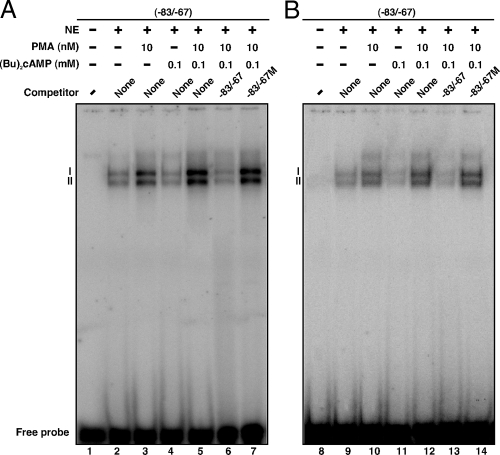

The involvement of the ERK1/2 (p44 and p42 MAPK) pathway in the steroidogenic response has been previously demonstrated (13,14,17); thus, the effect of PMA on (Bu)2cAMP-mediated ERK1/2 signaling and consequently steroidogenesis was determined. Serum-starved (∼12 h) MA-10 (Fig. 2A) and KK-1 (Fig. 2B) cells treated with either PMA (10 nm) or (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm) demonstrated enhanced (P < 0.05) P-ERK1/2 over basal. PMA and (Bu)2cAMP in combination further increased P-ERK1/2, and this increase was abrogated by a MAPK/ERK inhibitor U0126 [U0, 10 μm (16,17)]. Levels of ERK1/2 protein were unaltered in any of these treatments, suggesting the activation of ERK1/2 by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP involves protein phosphorylation rather than protein synthesis. The relevance of P-ERK1/2 induction on StAR expression and steroid synthesis was next assessed. KK-1 cells treated with PMA and (Bu)2cAMP demonstrated approximately 3.5- and 2.4-fold increases in StAR protein expression over untreated cells, respectively (Fig. 2C). U0 markedly diminished PMA- and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR protein levels but elevated (P < 0.01) (Bu)2cAMP-induced responsiveness. Whereas U0 alone increased StAR protein expression by 2-fold, it attenuated basal and stimulated progesterone levels between 38 and 60%. Effect of U0 on PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-responsive StAR expression and progesterone synthesis in MA-10 cells (not illustrated and Ref. 17) followed similar patterns as those of KK-1 cells, demonstrating ERK1/2 plays discrete effects on steroidogenesis via the PKC and PKA pathways (13,49,50).

Figure 2.

Role of ERK1/2 signaling in the activation of PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR expression and steroid synthesis. MA-10 (A) and KK-1 (B and C) cells were pretreated without or with a MAPK/ERK inhibitor U0126 (U0, 10 μm) for 30 min and then incubated with PMA (10 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), or their combination for an additional 30 min (A and B) or 6 h (C). Representative immunoblots illustrate P-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 (A and B) and StAR and P-StAR (C) using 25–30 μg of total cellular protein. Accumulation of progesterone in media was determined and expressed as nanograms per milligram protein (n = 4). Actin expression was assessed as a loading control. Letters above the bars indicate that these groups differ significantly from each other at least at P < 0.05. Con, Control.

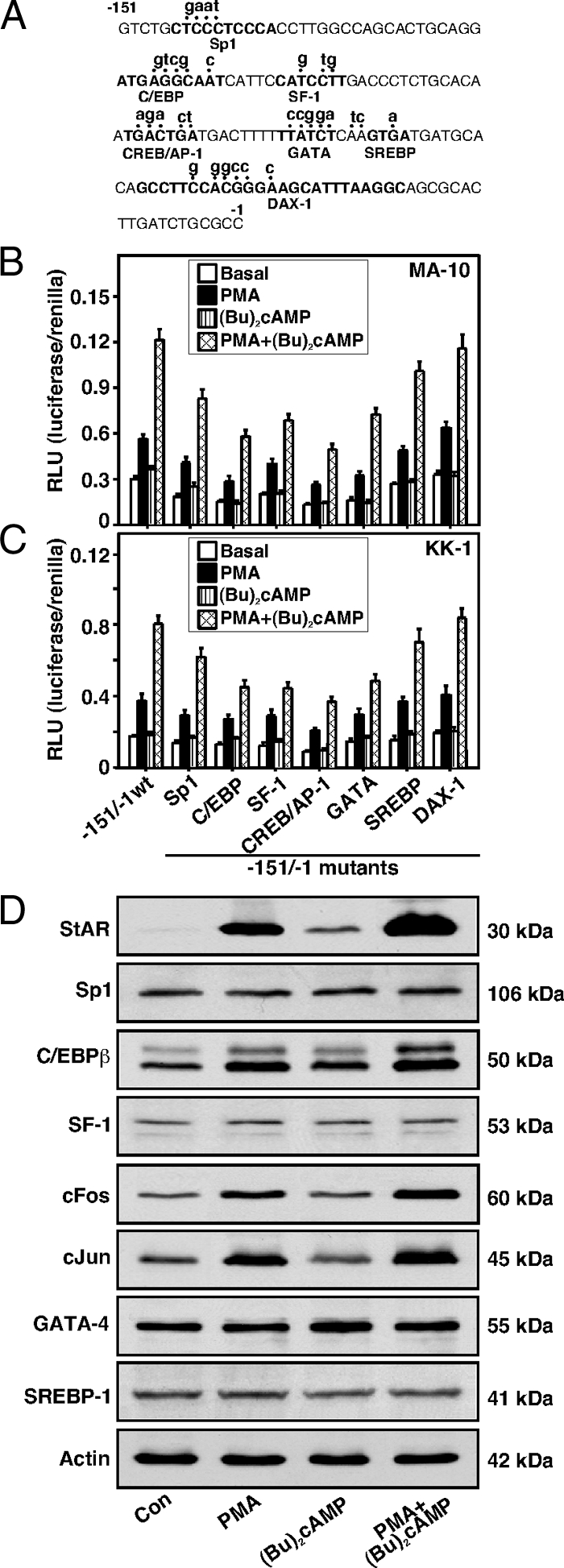

Evaluation of the effects of different transcription factors on PMA and (Bu)2cAMP-responsive StAR expression and steroidogenesis

Assessment of several transcription factor-binding sites within the −151/−1-bp region in PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated transcription of the StAR gene was determined by generating mutations. The elements studied were an Sp1, C/EBP, SF-1, CREB/AP-1, GATA, SREBP, and DAX-1 motifs (Fig. 3A). MA-10 cells transfected with the −151/−1-bp StAR reporter plasmid displayed a 1.9 ± 0.2 increase in reporter activity by PMA (Fig. 3B). Whereas (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm) had no significant effect, PMA elevated (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR reporter responsiveness by 4-fold. Disruption of the Sp1, C/EBP, SF-1, CREB/AP-1, GATA, and SREBP binding sites decreased basal reporter activity by 30, 48, 45, 56, 37, and 20%, respectively, but did not affect PMA- or PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-mediated fold responsiveness. Alteration in the DAX-1 binding site (DAX-1 is a negative regulator of steroidogenesis) (28) had no specific effect on StAR gene expression. The effects of mutations of these transcription factor-binding sites were qualitatively similar in KK-1 cells (Fig. 3C). In additional studies, expression of these transcription factors in conjunction with PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was assessed by immunoblotting. MA-10 cells treated with PMA, (Bu)2cAMP and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP demonstrated increases (P < 0.01) in StAR protein and progesterone (data not shown) levels over respective controls (Fig. 3D). Under similar experimental paradigms, whereas PMA demonstrated a pronounced elevation in (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR expression, it had varying effects on the expression of different transcription factors. In particular, PMA further enhanced (P < 0.05) (Bu)2cAMP-induced C/EBPβ, cFos, and cJun protein levels. These analogs also phosphorylate cFos and cJun (37,42) but not GATA-4 and C/EBPβ (not illustrated). Expression of the Sp1, SF-1, GATA-4, and SREBP-1 proteins was unaltered by PMA, (Bu)2cAMP, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP treatments. In contrast, PMA and (Bu)2cAMP alone attenuated DAX-1 protein expression by 43–58%, and levels were not further affected by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP cotreatment (data not shown and Ref. 28).

Figure 3.

Assessment of different transcription factors in PMA and (Bu)2cAMP responsiveness. Promoter sequences (−151/−1 bp) of the mouse StAR gene were studied for several elements by generating mutations (A). MA-10 (B) and KK-1 (C) cells were transfected with either the −151/−1 StAR reporter segment (−151/−1 wt) or the −151/−1 StAR containing mutations in each of the binding sites as indicated, in the presence of pRL-SV40 vector. After 36 h of transfection, cells were incubated without (basal) or with PMA (10 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP for an additional 6 h. Luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined and expressed as relative light unit (RLU, luciferase/renilla). Data represent the mean ± se five independent experiments. MA-10 cells were treated without (Con) or with PMA (10 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP for 6 h (D). Expression of the StAR, Sp1, C/EBPβ, SF-1, cFos, cJun, GATA-4, and SREBP-1 proteins was determined by immunoblotting using 25–30 μg of total protein. Immunoblots shown are representative of three to six independent experiments. Actin expression was assessed as a loading control. Con, Control.

Roles of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP in P-CREB and CBP association with the StAR promoter and their relevance to StAR gene transcription

The role of posttranslational modification of a CREB/activating transcription factor (ATF) family member in StAR expression and steroidogenesis has been demonstrated (25,37); thus, it was of interest whether PMA and (Bu)2cAMP in combination could enhance P-CREB. Treatment with PMA resulted in augmentation (P < 0.05) of P-CREB by 10 min, elevated maximally between 30 and 120 min, decreased slightly by 300 min, but remained markedly elevated over basal both in MA-10 and KK-1 cells (Fig. 4A). The amounts of CREB protein were unchanged during the time course studied. Both PMA and (Bu)2cAMP alone increased (P < 0.05) P-CREB levels in KK-1 cells, and their combination further elevated P-CREB (Fig. 4B). Whereas PMA, (Bu)2cAMP, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP enhanced P-CREB, they had no significant effects on the CBP protein expression.

Figure 4.

Effect of PMA in modulation of (Bu)2cAMP-mediated CREB, P-CREB and CBP levels, P-CREB and CBP association with the StAR promoter, and their relevance to StAR gene expression. MA-10 (A and C–F) and KK-1 (A and B) cells were pretreated without or with GFX (20 μm) and H-89 (20 μm) for 30 min and then incubated in the absence or presence of PMA (10 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP for 0–300 min (A), 6 h (B), or 1 h (C and D), and samples were processed for immunoblotting and ChIP analyses. Representative immunoblots show P-CREB, CREB, and CBP levels in response to different treatments using 25–30 μg of total protein. Integrated OD (IOD) values of each immuno-specific band in P-CREB, CREB, and CBP were quantified and either presented as a ratio of P-CREB/CREB (A) or compiled from three independent experiments (B, bottom panel). Cross-linked sheared chromatin obtained from different treatment groups was immunoprecipitated (IP) without or with anti-P-CREB (C) and anti-CBP (D) Abs. Recovered chromatin was subjected to PCR analysis using primers specific to the proximal region of the mouse StAR promoter. Representative autoradiograms (n = 3–5) illustrate the association of P-CREB and CBP with the StAR promoter. E, MA-10 cells were transfected with either empty vector (pcDNA) or a nonphosphorylatable CREB mutant (CREB-M1) in the presence of the −151/−1 StAR promoter segment. pGL3 basic (pGL3) was used as a control. Using the −151/−1 StAR reporter segment, cells were also transfected with pcDNA, wild-type CREB, CBP, and E1A expression plasmids, or a combination of them, as indicated (F). The pRL-SV40 plasmid was included in these experiments for normalization of transfection efficiency. After36 h of transfection, cells were treated without (Basal), or with PMA (10 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm) and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP for an additional 6 h. Luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined and expressed as relative light unit (RLU, luciferase/renilla). Data represent the mean ± se of four to six independent experiments. Letters above the bars indicate that these groups differ significantly from each other at least at P < 0.05.

To determine whether the induction of P-CREB recruits CBP to the StAR promoter, ChIP assays were performed in MA-10 cells. As depicted in Fig. 4C, PMA, (Bu)2cAMP, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP resulted in 3.2 ± 0.4-, 1.9 ± 0.3-, and 5.4 ± 0.8-fold increases in P-CREB association with the StAR proximal promoter when compared with controls. Increased association of P-CREB with the StAR promoter by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was decreased (P < 0.01) by both GFX and H-89. The association of CBP in response to PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was found to be concurrent with that of P-CREB (Fig. 4D), demonstrating the physical interaction of P-CREB-DNA in the recruitment of CBP to the StAR promoter. Association of P-CREB and CBP was not observed with the distal StAR promoter (data not shown and Refs. 25, 37). To obtain more insight into these mechanisms, the roles of CREB and CBP in PMA and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR gene expression was evaluated. Figure 4E demonstrates that PMA treatment of mock-transfected MA-10 cells, within the context of the −151/−1 StAR reporter segment, resulted in a 2-fold increase in StAR promoter activity over basal, an effect that was further increased (P < 0.05) by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP cotreatment. Cells expressing a nonphosphorylatable mutant of CREB (CREB-M1) decreased basal reporter activity by 40–52% and consequently diminished PMA and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR reporter responsiveness. CREB uses CBP as a coactivator; therefore, the influence of CBP in CREB-mediated transcription of the StAR gene was assessed (Fig. 4F). Transfection of the wild-type CREB, in the presence of the −151/−1 StAR segment, exhibited an approximately 2-fold increase in reporter activity in response to PMA and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP over those seen in mock-transfected cells. Ectopic expression of CBP enhanced the activity of CREB in basal, PMA-, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR reporter activity, and these responses were markedly repressed (P < 0.01) by the adenovirus E1A oncoprotein.

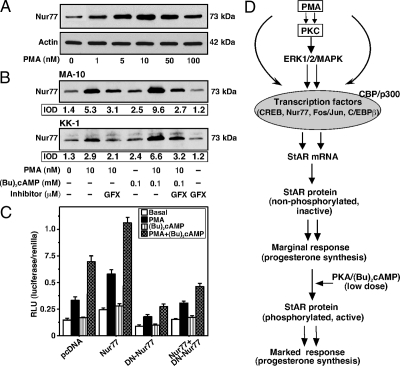

To better understand CREB signaling, EMSA DNA-protein binding was carried out with NE, using an oligoprobe (−83/−67 bp) that can bind recombinant CREB protein (36,41). The results show that a 32P-labeled probe resulted in the formation of two DNA-protein complexes (I and II) with NE obtained from MA-10 (Fig. 5A, lanes 2–7) and KK-1 (Fig. 5B, lanes 9–14) cells. PMA (10 nm) treatment demonstrated an increase in DNA-protein binding (compare Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 9 with lanes 3 and 10). (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm) had no effect on DNA-protein complexes (lanes 3 and 11). The increase in DNA-protein binding mediated by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 12) was inhibited by the unlabeled sequence (−83/−67; Fig. 5, lanes 6 and 13). Binding was not affected with an unlabeled mutant probe (−83/−67 M; Fig. 5, lanes 7 and 14). These findings demonstrate the functional involvement of CREB in PMA and (Bu)2cAMP mediated induction of StAR gene transcription.

Figure 5.

Binding of the CREB/ATF motif (−83/−67 bp) of the StAR promoter to MA-10 and KK-1 NE, using EMSAs. NE (12–15 μg) obtained from control, PMA (10 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-treated MA-10 (A, lanes 2–7) and KK-1 (B, lanes 9–14) cells were incubated with the 32P-labeled probe specific to the −83/−67 bp region of the StAR promoter. DNA-protein complexes (labeled as I and II) were challenged with unlabeled wild-type (−83/−67; lanes 6 and 13) or mutant (−83/−67 M; lanes 7 and 14) sequences. Cold competitors were used at 100-fold molar excess. Migration of free probes is shown in both cases. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Effect of PMA on (Bu)2cAMP-induced Nur77 expression and its relevance to StAR transcription

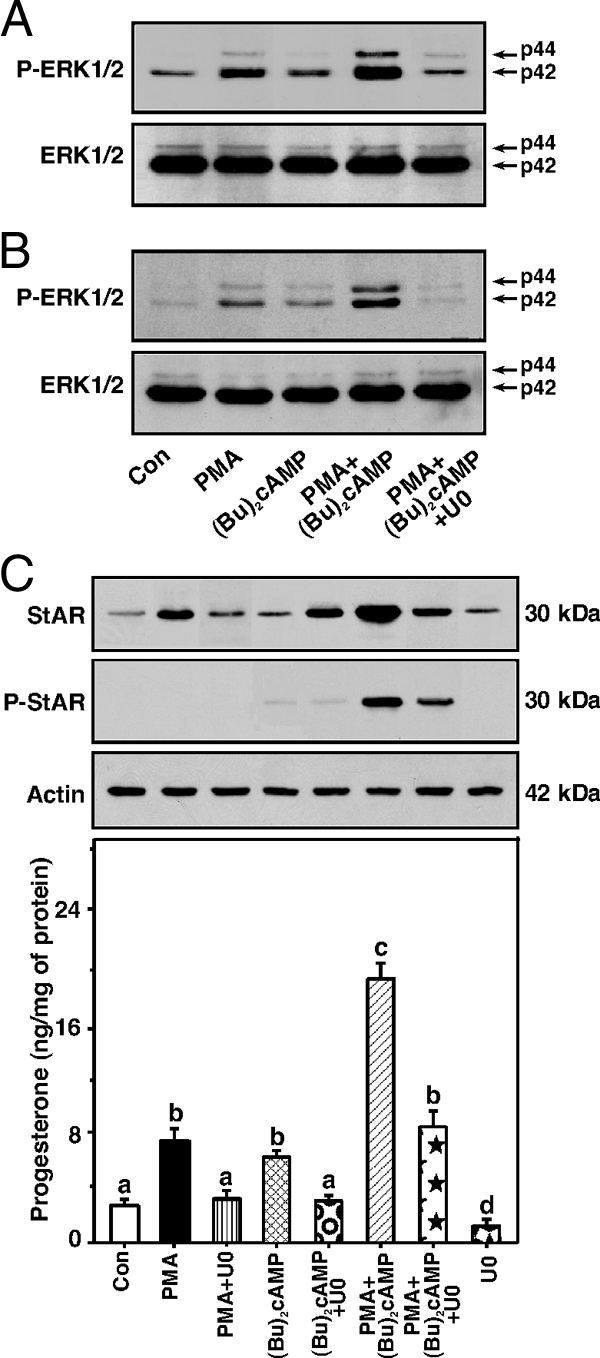

Because Nur77 can up-regulate StAR gene expression (27,28), its role in PMA-dependent modulation of (Bu)2cAMP responsiveness was investigated. MA-10 cells treated with PMA (1–100 nm) resulted in an increase in the expression of Nur77 protein in a dose response fashion, being a maximum of 3.3 ± 0.6-fold over basal at 10 nm (Fig. 6A). Increased levels of Nur77 in response to PMA in MA-10 and KK-1 cells were decreased by GFX (Fig. 6B). (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm) modestly, but consistently, elevated (P < 0.05) Nur77 protein levels. PMA in combination with (Bu)2cAMP further augmented Nur77 protein expression. KK-1 cells transfected with the wild-type Nur77, in the presence of the −151/−1 StAR segment, showed an approximately 2-fold increase in StAR reporter activity by PMA and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP over the responses seen in mock-transfected cells (Fig. 6C). Expression of a DN-Nur77 decreased basal, PMA-, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-induced StAR reporter activity between 46 and 72%. These data demonstrate that the activation of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP mediated StAR transcription is influenced, at least in part, by Nur77 in mouse Leydig and granulosa cells.

Figure 6.

Role of PMA in the activation of (Bu)2cAMP-mediated Nur77 protein expression and its relevance to StAR gene transcription and a schematic model on PKC-dependent modulation of cAMP-mediated steroidogenesis. MA-10 (A and B) and KK-1 (B and C) cells were pretreated without or with GFX (20 μm) for 30 min and then incubated with PMA (10 or 1–100 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), or their combination for 6 h, as indicated. Representative immunoblots (n = 3–4) show expression of Nur77 in different treatment groups using 25–30 μg of total cellular protein. Integrated OD (IOD) values of each band were quantified and presented (B). C, KK-1 cells were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA), wild-type Nur77, DN-Nur77, or a combination of them, in the presence of the −151/−1 StAR promoter segment. Cells were cotransfected in the presence of pRL-SV40 plasmid for normalization of transfection efficiency. After 36 h of transfection, cells were treated without (basal) or with PMA (10 nm), (Bu)2cAMP (0.1 mm), and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP for an additional 6 h, and luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined and expressed as relative light unit (RLU, luciferase/renilla). Data represent the mean ± se of four independent experiments. D, Illustration of how a number of factors may serve in the PKC-dependent potentiation of cAMP/PKA-mediated steroidogenesis. Induction of PKC by PMA can induce StAR expression but is incapable of P-StAR and thus produces a marginal response in progesterone synthesis. However, a nominal increase in PKA activity by means of a low dose of (Bu)2cAMP, phosphorylates and activates PMA-induced StAR, increases its cholesterol-transferring capacity, and results in the modulation cAMP-mediated steroid synthesis.

Discussion

Regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis by trophic hormones is mediated by multiple processes and signaling pathways in steroidogenic tissues (3,5,10,11). The interaction of trophic hormones with specific receptors enhances intracellular cAMP levels, which, in turn, activate cAMP-dependent PKA and results in the phosphorylation of proteins involved in steroidogenesis. Ligand-receptor interaction can stimulate phospholipase C and trigger the activation of the downstream PKC pathway. Diacylglycerol is known to be a physiological regulator of PKC in various tissues. Nonetheless, a wide variety of signaling processes have been shown to augment PKC activity including those involved in steroidogenesis, such as LH/ACTH, prolactin, several growth factors, and arachidonic acid (18,48,51,52,53). Whereas the effect of the cAMP/PKA pathway is, by far, the most robust in inducing steroid synthesis, PKC has been shown to have moderate effects on adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis (12). PKC has been shown to be capable of potentiating the steroidogenic response mediated by suboptimal concentrations of LH/hCG or cAMP analogs (17,18). The present studies extend those observations by elucidating the molecular events by which PKC signaling acts to modulate the cAMP/PKA response involved in regulating StAR expression and steroidogenesis in mouse gonadal cells.

Our current data demonstrate that PMA, by itself, cannot phosphorylate StAR at Ser194, but it dramatically enhanced the activity of a subthreshold concentration of (Bu)2cAMP to do so, leading to increases in StAR, P-StAR, and progesterone levels (17,18,42). In fact, the marked elevation in StAR expression concomitant with a moderate increase in steroid synthesis by PMA was due to a requirement for PKA-dependent posttranslational modification. PMA was also found to be a weak inducer of CYP11A1 protein expression (17,18,19,20,42). We reported that several agents that do not require cAMP signaling stimulate StAR expression and steroid synthesis in the absence of StAR phosphorylation; however, they enhance hCG-mediated cAMP levels and thus increase StAR expression and steroid synthesis (16,43). By contrast, PMA does not elevate, but rather decreases, intracellular cAMP and has been demonstrated to have no effects on LH/hCG-induced cAMP levels, observations in agreement with previous findings (19,48). Even so, the inhibition of PKA activity diminished PMA (17,42) and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP mediated StAR expression and steroid synthesis, suggesting the synergistic effects of these analogs on steroidogenesis require the involvement of endogenous cAMP. In fact, a low level of PKA activity is critical in the modulation of (Bu)2cAMP-mediated steroidogenesis by PKC, and it appears that the PKC-dependent regulation of gonadotropin and/or cAMP responsiveness is important in gonadal and adrenal steroidogenic functions. However, the roles of other factors (i.e. chloride ion conductance, calcium signaling, arachidonic acid) in StAR expression and steroidogenesis, which have been demonstrated to be sensitized to low levels PKA in different steroidogenic cell models, cannot be excluded.

The results of the present findings demonstrate the influence of the ERK1/2 pathway in PMA and (Bu)2cAMP mediated steroidogenesis. Inhibition of the ERK1/2 activity by U0126 markedly affected PMA and (Bu)2cAMP-responsive ERK1/2 phosphorylation, but not ERK1/2 protein synthesis, both in Leydig and granulosa cells. Interestingly, whereas inhibition of ERK1/2 attenuated PMA- and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-mediated steroidogenesis, it had opposing effects on StAR expression and steroid synthesis induced by (Bu)2cAMP. Accordingly, ERK1/2 inhibition enhanced (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR expression but decreased progesterone synthesis. These results are in support of previous findings that demonstrated that MAPK/ERK inhibition increases LH/hCG/(Bu)2cAMP- and IGF-I-induced StAR expression but decreases steroid synthesis in Leydig cells (13,16,17). Conversely, inhibition of ERK1/2 has been shown to be associated with increases in LH/FSH- and forskolin-mediated StAR and steroid levels in rat granulosa cells (14,50). Furthermore, whereas ERK1/2 inhibition was shown to have no effect on LH/hCG-induced steroidogenesis, it attenuated (Bu)2cAMP, cholera toxin, and forskolin-induced progesterone levels in human granulosa cells (49). Altogether, the ERK1/2 signaling cascade plays a complex role in regulating the steroidogenic response, which appears to be dependent on receptor-effector coupling and is stimulus and pathway specific in different steroidogenic cells.

An interesting aspect of the present findings is the involvement of CREB in the potentiation of PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated steroidogenesis. More specifically, the relevance of CREB induction was elucidated by three independent approaches that all demonstrated that alteration/inhibition of this event markedly affected the PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated synergism involved in the steroidogenic response. First, reporter gene analyses demonstrated that the expression of a non phosphorylatable CREB-M1 (Ser133→Ala) repressed PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-stimulated StAR gene transcription. Second, EMSAs using a CREB/ATF binding region [−83/−67 bp (36,41)] of the StAR promoter showed a clear increase in DNA-protein binding by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP cotreatment when compared with their responses individually and that the binding was affected by wild-type and mutant cold competitors. Third, in vivo ChIP data revealed that the induction of P-CREB by PMA, (Bu)2cAMP, and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP was concurrent with CBP, indicating the physical interaction of P-CREB-DNA in CBP recruitment with the StAR proximal promoter. Thus, the induction of CREB in conjunction with PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP involves a mechanism that results in the marked increase in the steroidogenic response by PKA activation. In addition, whereas the steroidogenic potential of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was found to be associated with increased expression/phosphorylation of C/EBPβ, cFos, and cJun, they had no effects on GATA-4/P-GATA-4 and P-C/EBPβ. Disruption of several putative binding sites (with the exception of DAX-1), diminished basal StAR reporter activity to varying degrees but did not affect PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP-mediated fold responsiveness. It is highly likely that the effects of PMA and PMA plus (Bu)2cAMP, in the absence of specific transcription factor binding, remain intact due to coactivator recruitment by other transcription factors bound within the −151/−1-bp region of the StAR promoter. Conversely, DAX-1 binds to the hairpin structure in the mouse (28) and human (54) StAR promoters and effectively suppresses steroid synthesis by impairing transcription of the StAR gene. Hence, it is conceivable that the synergistic action of PMA and (Bu)2cAMP on steroidogenesis is influenced by several positive and negative factors and that a balance between the inducer and repressor functions may fine-tune regulatory events in the gonads.

A substantial amount of evidence indicates that transcriptional synergy requires the simultaneous interaction of multiple transcription factors with CBP/p300 or relevant coactivators (32). CBP/p300 harbors several functional domains, possess histone acetyltransferase activity in facilitating chromatin remodeling and as a consequence promote transcriptional activation (24,26,32,37). In the present study, whereas treatment with PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was found to increase the association of P-CREB and CBP to the proximal StAR promoter, they had no effects on CBP protein levels, suggesting these analogs do not affect CBP synthesis, but rather they increase P-CREB-CBP interaction. Furthermore, ectopic expression of CBP enhanced CREB involvement in PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR gene expression, events that were inhibited by the adenovirus E1A that binds to the cysteine/histidine-rich domain of CBP/p300 and inactivates its function. This indicates that E1A prevents the histone acetyltransferase activity of CBP and/or its interaction with other transcription factors or general transcriptional machinery (24,37). Likewise, decreased association of CBP with the StAR promoter during CREB and Fos/Jun cross talk has been demonstrated to coincide with transcriptional repression of the StAR gene (37). In addition, CBP/p300 has been shown to be involved in the activity of Fos/Jun, C/EBPβ, and GATA-4, demonstrating these cofactors act as integrators among diverse signaling pathways and play important roles in regulating StAR gene transcription (26,37).

In view of the present results, it is apparent that the nuclear factor Nur77 plays an essential role in the PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated regulation of StAR expression and steroidogenesis. Overexpression of Nur77 was capable of activating PMA and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated StAR gene transcription, which was markedly affected by a DN-Nur77. Nur77 is expressed in adrenal and gonadal cells and is activated by multiple signaling pathways (27,28,33,34). Specifically, Nur77 is induced by both PKC and PKA signaling, which down-regulates DAX-1 (28), indicating that induction of Nur77 and attenuation of DAX-1 are crucial for steroidogenesis. Recent studies demonstrated that Nur77 activates StAR gene transcription by binding to SF-1 recognition sites, and its trans-activation potential is influenced by posttranslational modification (27,28). Furthermore, several cofactors (i.e. steroid receptor coactivator, CBP/p300, and vitamin D receptor-associated protein-205) have been shown to be involved in Nur77-mediated activation of a number of steroidogenic genes, including 17α-hydroxylase, 21-hydroxylase, and 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (34,55,56). Therefore, it may not be surprising that PMA- and (Bu)2cAMP-mediated induction of Nur77 could recruit CBP/p300 and aid in the transcriptional regulation of the StAR gene. Taken together, the present results led us to propose a model in which the mechanisms of PKC signaling modulate those of cAMP-stimulated StAR expression and steroidogenesis through the combined action of multiple factors and processes in mouse Leydig and granulosa cells (Fig. 6D). The synergistic activation of the steroidogenic response by PMA and (Bu)2cAMP was found to be predominantly mediated via induction of CREB, although other factors appear to mediate part of the response. The eventual effect of PKC in modulation of cAMP/PKA signaling may allow for fine-tuning the steroidogenic machinery involved in gonadal development and function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Ascoli (Department of Pharmacology, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA) for the generous gift of MA-10 cells. We also thank Drs. A. R. Brasier (The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX) and H. S. Choi (Chonnam National University, Kwangju, Republic of Korea) for the generous gifts of CBP, E1A, and wild-type and mutant Nur77 expression plasmids, respectively.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD-17481 and funds from the Robert A. Welch Foundation Grant B1-0028.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 12, 2009

Abbreviations: Ab, Antibody; AP, activator protein; ATF, activating transcription factor; (Bu)2cAMP, dibutyryl cAMP; CBP, CREB binding protein; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; DAX-1, dosage-sensitive sex reversal-adrenal hypoplasia congenita critical region on the X chromosome, gene 1; DN, dominant negative; GFX, GF-109203X; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; NE, nuclear extract; P, phosphorylated; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; Ser, serine; SF-1, steroidogenic factor 1; Sp1, specificity protein-1; SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding protein; StAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein; SV40, Simian virus 40; Thr, theronine.

References

- Clark BJ, Wells J, King SR, Stocco DM 1994 The purification, cloning, and expression of a novel luteinizing hormone-induced mitochondrial protein in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Characterization of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR). J Biol Chem 269:28314–28322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Sugawara T, Strauss 3rd JF, Clark BJ, Stocco DM, Saenger P, Rogol A, Miller WL 1995 Role of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis. Science 267:1828–1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco DM, Clark BJ 1996 Regulation of the acute production of steroids in steroidogenic cells. Endocr Rev 17:221–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson LK, Strauss 3rd JF 2000 Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and the intramitochondrial translocation of cholesterol. Biochim Biophys Acta 1529:175–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Stocco DM 2005 Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: functional and physiological consequences. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord 5:93–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL 2007 StAR search—what we know about how the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein mediates mitochondrial cholesterol import. Mol Endocrinol 21:589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose HS, Sato S, Aisenberg J, Shalev SA, Matsuo N, Miller WL 2000 Mutations in the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in six patients with congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:3636–3639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, Zhao L, Caron KM, Majdic G, Suzuki T, Shizawa S, Sasano H, Parker KL 2000 Developmental roles of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) as revealed by StAR knockout mice. Mol Endocrinol 14:1462–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron KM, Soo SC, Wetsel WC, Stocco DM, Clark BJ, Parker KL 1997 Targeted disruption of the mouse gene encoding steroidogenic acute regulatory protein provides insights into congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:11540–11545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke BA 1999 Signal transduction involving cyclic AMP-dependent and cyclic AMP-independent mechanisms in the control of steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 151:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL 2002 The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor, a 2002 perspective. Endocr Rev 23:141–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco DM, Wang X, Jo Y, Manna PR 2005 Multiple signaling pathways regulating steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: more complicated than we thought. Mol Endocrinol 19:2647–2659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyles SL, Burns CJ, Whitehouse BJ, Sugden D, Marsh PJ, Persaud SJ, Jones PM 2001 ERKs regulate cyclic AMP-induced steroid synthesis through transcription of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) gene. J Biol Chem 276:34888–34895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seger R, Hanoch T, Rosenberg R, Dantes A, Merz WE, Strauss III JF, Amsterdam A 2001 The ERK signaling cascade inhibits gonadotropin-stimulated steroidogenesis. J Biol Chem 276:13957–13964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelle N, Holst M, Söder O, Svechnikov K 2004 Extracellular signal-regulated kinases are involved in the acute activation of steroidogenesis in immature rat Leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology 145:4629–4634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Chandrala SP, King SR, Jo Y, Counis R, Huhtaniemi IT, Stocco DM 2006 Molecular mechanisms of insulin-like growth factor-I mediated regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in mouse Leydig cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:362–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Jo Y, Stocco DM 2007 Regulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2: role of protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling. J Endocrinol 193:53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo Y, King SR, Khan SA, Stocco DM 2005 Involvement of protein kinase C and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent kinase in steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression and steroid biosynthesis in Leydig cells. Biol Reprod 73:244–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary LR, Stocco DM 1988 Stimulation of progesterone production by phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate in MA-10 Leydig tumor cells. Biochimie 70:1353–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresta C, Mioni R, Bordon P, Gottardello F, Nogara A, Rossato M 1995 Erythropoietin and testicular steroidogenesis: the role of second messengers. Eur J Endocrinol 132:103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooton-Kee CR, Clark BJ 2000 Steroidogenic factor-1 influences protein-deoxyribonucleic acid interactions within the cyclic adenosine 3,5-monophosphate-responsive regions of the murine steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. Endocrinology 141:1345–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea-Eaton W, Sandhoff TW, Lopez D, Hales DB, McLean MP 2002 Transcriptional repression of the rat steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein gene by the AP-1 family member c-Fos. Mol Cell Endocrinol 188:161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Wang XJ, Stocco DM 2003 Involvement of multiple transcription factors in the regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression. Steroids 68:1125–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi H, Christenson LK, Chang L, Sammel MD, Berger SL, Strauss III JF 2004 Temporal and spatial changes in transcription factor binding and histone modifications at the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) locus associated with stAR transcription. Mol Endocrinol 18:791–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem BF, Hudson EA, Clark BJ 2005 Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) enhances cAMP-responsive element binding (CREB) protein phosphorylation and phospho-CREB interaction with the mouse steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene promoter. Endocrinology 146:1348–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman E, Yivgi-Ohana N, Sher N, Bell M, Eimerl S, Orly J 2006 Transcriptional activation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene: GATA-4 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta confer synergistic responsiveness in hormone-treated rat granulosa and HEK293 cell models. Mol Cell Endocrinol 252:92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Boucher N, Brousseau C, Tremblay JJ 2008 The orphan nuclear receptor NUR77 regulates hormone-induced StAR transcription in Leydig cells through cooperation with Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I. Mol Endocrinol 22:2021–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT, Jo Y, Stocco DM 2009 Role of dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia congenita, critical region on the X chromosome, gene 1 in protein kinase A- and protein kinase C-mediated regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression in mouse leydig tumor cells: mechanism of action. Endocrinology 150:187–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Eubank DW, Stocco DM 2004 Assessment of the role of activator protein-1 on transcription of the mouse steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. Mol Endocrinol 18:558–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH 1993 Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature 365:855–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker D, Ferreri K, Nakajima T, LaMorte VJ, Evans R, Koerber SC, Hoeger C, Montminy MR 1996 Phosphorylation of CREB at Ser-133 induces complex formation with CREB-binding protein via a direct mechanism. Mol Cell Biol 16:694–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo N, Goodman RH 2001 CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem 276:13505–13508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song KH, Park JI, Lee MO, Soh J, Lee K, Choi HS 2001 LH induces orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 gene expression in testicular Leydig cells. Endocrinology 142:5116–5123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalovsky D, Refojo D, Liberman AC, Hochbaum D, Pereda MP, Coso OA, Stalla GK, Holsboer F, Arzt E 2002 Activation and induction of NUR77/NURR1 in corticotrophs by CRH/cAMP: involvement of calcium, protein kinase A, and MAPK pathways. Mol Endocrinol 16:1638–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli M 1981 Characterization of several clonal lines of cultured Leydig tumor cells: gonadotropin receptors and steroidogenic responses. Endocrinology 108:88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT, Eubank DW, Clark BJ, Lalli E, Sassone-Corsi P, Zeleznik AJ, Stocco DM 2002 Regulation of steroidogenesis and the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein by a member of the cAMP response-element binding protein family. Mol Endocrinol 16:184–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Stocco DM 2007 Crosstalk of CREB and Fos/Jun on a single cis-element: transcriptional repression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. J Mol Endocrinol 39:261–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kananen K, Markkula M, Rainio E, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Huhtaniemi IT 1995 Gonadal tumorigenesis in transgenic mice bearing the mouse inhibin α-subunit promoter/simian virus T-antigen fusion gene: characterization of ovarian tumors and establishment of gonadotropin-responsive granulosa cell lines. Mol Endocrinol 9:616–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Pakarainen P, Rannikko AS, Huhtaniemi IT 1998 Mechanisms of desensitization of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) action in a murine granulosa cell line stably transfected with the human FSH receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid. Mol Cell Endocrinol 146:163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena-Sempere M, Manna PR, Huhtaniemi I 1999 Molecular cloning of the mouse follicle-stimulating hormone receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid: functional expression of alternatively spliced variants and receptor inactivation by a C566T transition in exon 7 of the coding sequence. Biol Reprod 60:1515–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Eubank DW, Lalli E, Sassone-Corsi P, Stocco DM 2003 Transcriptional regulation of the mouse steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene by the cAMP response-element binding protein and steroidogenic factor 1. J Mol Endocrinol 30:381–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Stocco DM 2008 The role of JUN in the regulation of PRKCC-mediated STAR expression and steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells. J Mol Endocrinol 41:329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Chandrala SP, Jo Y, Stocco DM 2006 cAMP-independent signaling regulates steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells in the absence of StAR phosphorylation. J Mol Endocrinol 37:81–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose HS, Whittal RM, Baldwin MA, Miller WL 1999 The active form of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, StAR, appears to be a molten globule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:7250–7255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai KT, Monaco L, Alastalo TP, Lalli E, Parvinen M, Sassone-Corsi P 1996 Hormonal and developmental regulation of DAX-1 expression in Sertoli cells. Mol Endocrinol 10:1561–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K, Zanger UM, Honda S, Hara M, Waterman MR, Omura T 1993 Activation of CYP11A and CYP11B gene promoters by the steroidogenic cell-specific transcription factor, Ad4BP. Mol Endocrinol 7:1196–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Tena-Sempere M, Huhtaniemi IT 1999 Molecular mechanisms of thyroid hormone-stimulated steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig tumor cells. Involvement of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein. J Biol Chem 274:5909–5918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ruiz MP, Choi MS, Rose MP, West AP, Cooke BA 1992 Direct effect of arachidonic acid on protein kinase C and LH-stimulated steroidogenesis in rat Leydig cells: evidence for tonic inhibitory control of steroidogenesis by protein kinase C. Endocrinology 130:1122–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewi DA, Abayasekara DR, Wheeler-Jones CP 2002 Requirement for ERK1/2 activation in the regulation of progesterone production in human granulosa-lutein cells is stimulus specific. Endocrinology 143:877–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima K, Yoshii K, Fukuda S, Orisaka M, Miyamoto K, Amsterdam A, Kotsuji F 2005 Luteinizing hormone-induced extracellular-signal regulated kinase activation differently modulates progesterone and androstenedione production in bovine theca cells. Endocrinology 146:2903–2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe PD, Buckley AR, Zorn NE, Rui H 1991 Prolactin activates protein kinase C and stimulates growth-related gene expression in rat liver. Mol Cell Endocrinol 79:29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster RH 2004 Reciprocal influences between the signalling pathways regulating proliferation and steroidogenesis in adrenal glomerulosa cells. J Mol Endocrinol 32:893–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DC, Johnson AL 2007 Protein kinase C activity mediates LH-induced ErbB/Erk signaling in differentiated hen granulosa cells. Reproduction 133:733–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazopoulos E, Lalli E, Stocco DM, Sassone-Corsi P 1997 DNA binding and transcriptional repression by DAX-1 blocks steroidogenesis. Nature 390:311–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco CO, Lau LF, Gibori G 2002 A calcium/calmodulin-dependent activation of ERK1/2 mediates JunD phosphorylation and induction of nur77 and 20α-HSD genes by prostaglandin F2α in ovarian cells. J Biol Chem 277:3293–3302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Tremblay JJ 2005 The human 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Δ5-Δ4 isomerase type 2 promoter is a novel target for the immediate early orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 in steroidogenic cells. Endocrinology 146:861–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]