Abstract

Morphological plasticity in response to estradiol is a hallmark of astrocytes in the arcuate nucleus. The functional consequences of these morphological changes have remained relatively unexplored. Here we report that in the arcuate nucleus estradiol significantly increased the protein levels of the two enzymes in the glutamate-glutamine cycle, glutamine synthetase and glutaminase. We further demonstrate that these estradiol-mediated changes in the enzyme protein levels may underlie functional changes in neurotransmitter availability as: 1) total glutamate concentration in the arcuate nucleus was significantly increased and 2) microdialysis revealed a significant increase in extracellular glutamate levels after a synaptic challenge in the presence of estradiol. These data implicate the glutamate-glutamine cycle in the generation and/or maintenance of glutamate and suggest that the difference in extracellular glutamate between estradiol- and oil-treated animals may be related to an increased efficiency of the cycle enzymes. In vivo enzyme activity assays revealed that the estradiol mediated increase in glutamate-glutamine cycle enzymes in the arcuate nucleus led to an increase in γ-aminobutyric acid and is likely not related to the increase in extracellular glutamate. Thus, we have observed two-independent effects of estradiol on amino acid neurotransmission in the arcuate nucleus. These data suggest a possible functional consequence of the well-established changes in glial morphology that occur in the arcuate nucleus in the presence of estradiol and suggest the importance of neuronal-glial cooperation in the regulation of hypothalamic functions such as food intake and body weight.

A novel effect of estradiol on glutamate and GABA synthesis in the arcuate nucleus and its potential implications on homeostatic functions are discussed.

A growing body of literature has established the importance of glial cells in the regulation of neurotransmission. Once thought of as “humble servants laboring to cover neuronal needs” (1), the role of glial cells in neurotransmission is ever expanding (2). One of the first demonstrations of this was their responsiveness to hormones. Glial cells, specifically in the arcuate nucleus but in other steroid-responsive brain regions as well, respond to estradiol with a change in surface area that often correlates with a change in synaptic patterns (3,4,5). Despite this well-established phenomenon, there is a paucity of information regarding whether these changes in glial morphology correlate with changes in glial physiology.

In light of the growing appreciation for the functional role of glial cells in modulating synaptic transmission (2), it is important to explore the effect of estradiol on glial cell function. We have previously shown that estradiol modulates the expression of glial-specific genes in the adult female rat, including glutamine synthetase (GS), which plays an important role in glutamate neurotransmission (6).

GS is an integral part of the glutamate-glutamine cycle and is important for the production of glutamate as well as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (2,7). GS facilitates the conversion of glutamate to glutamine in a reaction requiring ammonia and one ATP (8). This glutamine is transferred back to the neuron. Here, it is converted by the predominately neuronal enzyme, glutaminase, into glutamate in a reaction requiring no energy (9). Fifty percent of cerebral glutamate is derived from glial glutamine (10), and glutamine from glial cells is necessary for the maintenance of normal levels of glutamate in the terminals (11). Inhibition of GS results in approximately a 50% decrease in the release of glutamate from brain slices (2). Modulation of GS activity may provide a unique opportunity for estradiol to modulate neuronal-glial interactions ultimately leading to an increase in glutamate metabolism.

We previously demonstrated an estradiol mediated increase in GS mRNA expression in the arcuate nucleus, ventromedial nucleus (VMN), medial amygdala, and the CA2/3 regions of the hippocampus in the adult female mouse (6). A similar increase in GS protein levels was observed in the medial basal hypothalamus (comprised of both the arcuate nucleus and VMN) and the hippocampus (6). In the present study, we further explore the functional significance of these changes in the arcuate nucleus because of the dynamic sensitivity of arcuate astrocytes to ovarian hormones (12) and their suspected role in a broad range of neuroendocrine functions (13). Furthermore, excitatory neurotransmission in the arcuate nucleus has been implicated in the control of such neuroendocrine functions as reproduction and feeding (14).

Based on our previous findings in the mouse, we hypothesize that estradiol increases glutamate in the arcuate nucleus via changes in the glutamate-glutamine cycle enzymes. This may be one mechanism by which estradiol can regulate neuroendocrine functions in the adult female rat.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were performed according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Adult female Sprague Dawley rats, approximately 300 g, 12–15 wk of age (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were ovariectomized and allowed to recover for 5–7 d. They were then randomly placed in control (injected with sesame oil vehicle) or estradiol-treated groups. Animals were given a single sc injection (0.1cc) of either 17β-estradiol benzoate (25 μg) or oil vehicle. This dose of estradiol was chosen to achieve proestrus levels of serum estradiol within a 24-h period. RIA analysis of trunk blood from these animals demonstrated that 24 h postinjection serum estradiol was 130–180 pg/ml in the experimental group compared with 15–35 pg/ml in the control group. Whereas physiologically relevant levels of serum estradiol were achieved at 24 h, it likely that the circulating levels were higher immediately after the injections. RIAs were done at the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core, which is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Health, Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research Grant U54-HD28934.

Immunocytochemistry

Animals were treated as described above and then euthanized 32 h later. The brains were removed and submersion fixed for 16 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% acrolein, followed by cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in potassium PBS. After cryoprotection, the brains were frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 C until processed for immunocytochemistry. The brains were sectioned at 30 μm in a cryostat and stored in a cryoprotectant solution. The tissue was processed according a standard laboratory protocol (15). GS antibody (Chemicon, Temcula, CA) was used at a 1:125,000 dilution, whereas the glutaminase antibody was used at a 1:2,000 dilution (gift from Dr. Ingeborg Aasland Torgner, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway). Neurolucida software, an image-combining computer microscopy program (MicroBrightField, Colchester, VT), was used to assess the number of GS-positive cell bodies. Additionally, the number of processes per cell were assessed by binning GS-positive cells into two groups, those cells that had fewer than three GS-positive processes and those that had greater than three GS-positive processes. The investigator was blind to the treatment groups (oil, n = 3; estradiol, n = 4).

OD measurements were used for the quantification of glutaminase immunocytochemistry. Glutaminase is a mitochondrial enzyme and staining is punctate making it difficult to determine individual cell bodies. Therefore, to quantify the expression of glutaminase in the arcuate, NIH image software was used to obtain an OD measurement of glutaminase-positive cells and that was compared between estradiol- (n = 3) and oil (n = 4)-treated animals.

Western blots

Animals were treated as described above and then collected at either 6 or 24 h after injection (n = 6 per group). The brains were frozen on dry ice and then cut in a cryostat at 350 μm. The arcuate was then micropunched according to the Palkovits micropunch procedure (16) and homogenized via sonication in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein (10 μg) was loaded into a 10% Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Electrophoresed proteins were blotted onto a polyvinyl difluoride membrane (Invitrogen). The membranes were washed in 20 mm Tris-buffered saline solution with 0.05% Tween 20 (T-TBS) and then blocked overnight in 5% powdered milk at 4 C. After the milk block the membranes were incubated in a primary antibody solution (T-TBS, GS 1:30,000, glutaminase 1:3,000) for 2 h at room temperature, washed three times in T-TBS, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the appropriate IgG secondary antibody solution (T-TBS, 1:2000). In a subsequent incubation, antibodies to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:500,000; Chemicon) were applied. The Phototype-HRP chemiluminescent system (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) was used for detection of the protein recognized by the antisera. The blots were exposed to Hyperfilm-ECL (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for varying exposure times. The films were then scanned into a computer at 1200 dpi and the scanned images were analyzed using NIH Image software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image). The ODs were measured for each individual band and when necessary normalized to the OD of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase bands. Each time point was considered a separate experiment. Statistical analysis was performed with a Student’s t test, comparing oil- and estradiol-treated animals at 6 and 24 h.

Total amino acid concentration

Animals were treated as described above. The arcuate nucleus was microdissected and flash frozen on dry ice. The tissue was weighed and homogenized via sonication in perchloric acid (100 μl/10 mg tissue). The acid was then neutralized using potassium bicarbonate and frozen at −80 C for 10 min. The samples (n = 8 for each group) were then thawed and centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected and diluted 1:50 with H2O. Fifty microliters of the diluted sample were analyzed by HPLC (17).

HPLC

Samples were analyzed by HPLC and flurometric amino acid detection after derivatization with o-phthaldehyde (17). Data for 20 amino acids were collected.

Microdialysis

Microdialysis supplies were obtained from Bioanalytical Systems (West Layfayette, IN). Ovariectomized animals were injected with estradiol or oil, and a guide cannula was surgically implanted into the arcuate nucleus using the following stereotaxic coordinates, in relation to bregma: −3.0 mm anteroposterior; ± 0.5 mm mediolateral; −7.5 mm, dorsoventral to the dura mater. Twenty-four hours after surgery, microdialysis studies were initiated. This time point was chosen to avoid possible confounding effects of a glial scar, which can emerge within a few days of neuronal disruption (18). Moreover, the time course is consistent with the timing of our observed changes in protein levels for GS and glutaminase (24–32 h after injection). Artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) composed of 150 mm Na, 3.0 mm K, 1.4 mm Ca, 0.8 mm Mg, 1.0 mm P, and 155 mm Cl was perfused at a rate of 2 μl/min (19). All microdialysis components and solutions were maintained under sterile conditions. Samples were collected every 20 min and then analyzed by HPLC. Six baseline samples were collected (the first sample was dropped from analysis because it was during the equilibration period of the probe). aCSF containing 100 mm KCl was pumped through the microdialysis probe for 40 min, the time course for two samples; this is referred to as the KCl challenge. The increased concentration of KCl will alter the membrane potential of the arcuate neurons resulting in a depolarization and release of neurotransmitters. After 40 min, the perfusate was switched back to normal aCSF and six more baseline samples were collected. The animals were then euthanized using CO2 asphyxiation and their brains collected and processed for Neutral Red staining to examine probe placement. A placement was deemed appropriate when the needle track was located within sections that corresponded to plates 56–59 in a standard brain atlas (20) and was 0.5–1 mm from the ventricular wall (supplemental Fig. 1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). The samples collected from the microdialysis were run on the HPLC to assess glutamate concentration. Animals who did not have probes placed in the arcuate were also analyzed as negative controls (supplemental Fig. 2). The probe was correctly placed in the arcuate nucleus approximately 36% of the time resulting in a final sample size of five animals per group. Data are expressed as percent change from baseline.

Enzyme activity assays

Bilateral guide cannulae were stereotaxically implanted into the arcuate nucleus of ovariectomized animals (coordinates in relation to Bregma: −3.0 mm anteroposterior; ±0.6 mm mediolateral; −8.5 mm dorsoventral to the dura mater). After a 24-h period, the animals were injected with either estradiol or oil vehicle. Twenty-four hours after hormonal treatment, they were intracerebrally injected with approximately 0.3 μCi radiolabeled substrate [14C-glutamate (14C-GLU) for GS activity assays, n = 5 per group; 14C-GLU + 50 mm methylaminoisobutyric acid (MeAIB) for GS activity assays in the presence of glutamine uptake inhibitors, n = 6 per group; 14C-glutamine (14C-GLN) for glutaminase activity assays, n = 6 per group] mixed with Evans Blue dye. The dye was used to confirm cannula placement.

Two hours after the injection of radiolabeled substrate, the animals were euthanized and the arcuate nucleus dissected. The arcuate nucleus was then processed and run on the HPLC. Fractions eluting off the column were collected every 30 sec, and these fractions were then run on the scintillation counter. This combined methodology allowed for the temporal correlation of peaks in radioactivity with amino acids eluting from the column. The percent conversion was calculated by dividing the counts that correlated with the product peak by the total counts (defined as the sum of the counts in the glutamate, glutamine, and GABA peaks). All data were normalized to total radioactivity in the sample so all animals that had observable dye in the arcuate nucleus were included.

Statistical analysis

The microdialysis data were expressed as a percent change from baseline. Total glutamate over the course of the experiment was measured by taking the area under the curve for both estradiol- and oil-treated animals. The areas were then compared between estradiol- and oil-treated animals using a one-tailed t test. The extracellular glutamate levels before and after KCl administration were compared by averaging the five time points before and after KCl for each animal. A Wilcoxon test was used to compare extracellular glutamate levels before and after KCl within a treatment group, and a Mann-Whitney U analysis was used to compare the concentration of extracellular glutamate after KCl between estradiol- and oil-treated animals. Based on our previous results (6), we had an a priori prediction that estradiol would increase glutamate-glutamine cycling in the arcuate nucleus; therefore, the immunocytochemistry, Western blots and enzyme activity assays were analyzed with a one-tailed t test.

Results

Estradiol increases the expression of both enzymes in the glutamate-glutamine cycle

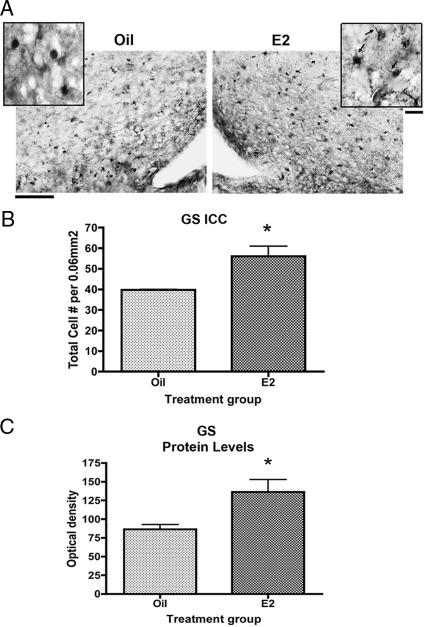

Immunocytochemistry was used to explore the cellular localization of GS expression in the arcuate nucleus. Estradiol significantly increased the number of GS-positive cells in the arcuate nucleus by 41% 32 h after treatment (Fig. 1, A and B). There was also a trend toward an increased frequency of cells with greater than three GS-positive processes (data not shown). In addition, Western blot analysis revealed that estradiol significantly increased GS protein levels by approximately 60% 24 h after treatment but had no effect at 6 h (Fig. 1C and data not shown). The range of time points assessed suggest that estradiol significantly increased GS protein levels on a time course consistent with classic actions of estradiol.

Figure 1.

Estradiol (E2) increases the expression of GS in the arcuate nucleus. Data are the mean ± sem. A, Representative photomicrographs of GS-positive astrocytes in estradiol- and oil-treated sections. Scale bar, 100 μm. Inset, Higher magnification view of GS-positive astrocytes. There was a trend toward an increased frequency of cells with greater than three GS-positive processes in estradiol-treated animals (P = 0.0744). Arrow, GS-positive processes. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, Estradiol significantly increased the number of GS-positive cells in the arcuate 32 h after treatment (t test, *, P = 0.0375). ICC, Immunocytochemistry. C, GS protein levels, as measured by Western blots, are significantly increased 24 h after treatment (t test, *, P = 0.0196).

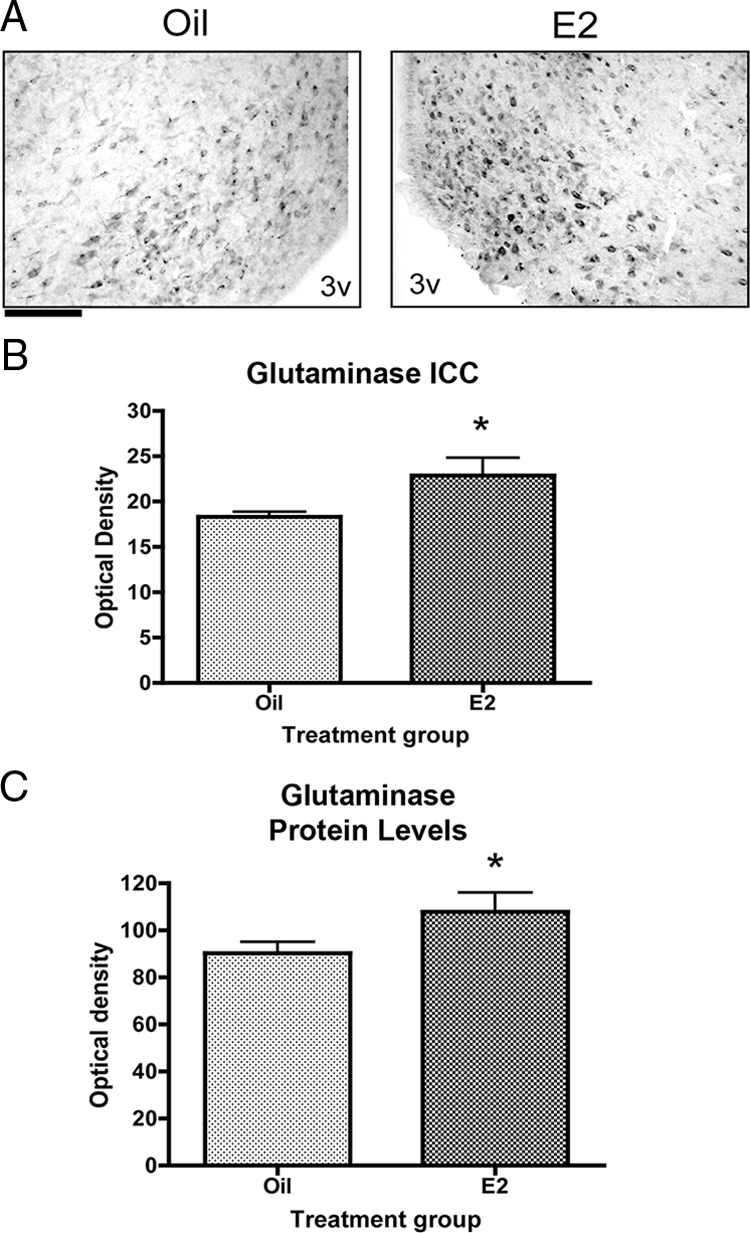

Glutaminase is the complimentary neuronal enzyme in the glutamate-glutamine cycle; converting glutamine to glutamate. Because estradiol has been shown to have effects on both neurons and glial cells, we examined the effect of estradiol on glutaminase protein levels. Estradiol significantly increased the density of glutaminase immunoreactivity in the arcuate nucleus by approximately 25% 32 h after treatment (Fig. 2, A and B). Similarly, Western blot analysis revealed that estradiol significantly increased glutaminase protein levels by 20% 24 h after treatment but had no effect at 6 h (Fig. 2C and data not shown). These results demonstrate that estradiol significantly increased the protein levels of the two enzymes in the glutamate-glutamine cycle, suggesting that there is neuronal-glial cooperation resulting in an increase in the production of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus.

Figure 2.

Estradiol increases the expression of glutaminase in the arcuate nucleus. Data are the mean ± sem. A, Representative photomicrographs of glutaminase staining in the estradiol- and oil-treated sections. Glutaminase is a mitochondrial enzyme and appears as punctate immunocytochemical staining. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, Estradiol significantly increased the density of glutaminase immunoreactivity in the arcuate 32 h after treatment (t test, *, P = 0.0259). ICC, Immunocytochemistry. C, Glutaminase protein levels are significantly increased 24 h after treatment (t test, *, P = 0.0476). 3v, Third ventricle.

Estradiol increases the concentration of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus

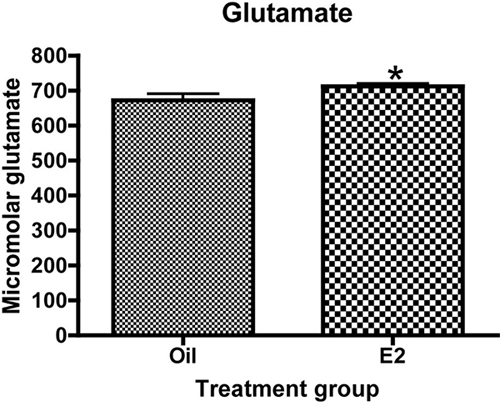

To determine whether estradiol increases total glutamate levels in the arcuate nucleus, glutamate concentration was measured using HPLC. Estradiol treatment resulted in a small, approximately 6%, but significant increase in the concentration of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus (Fig. 3). Curiously, glutamine concentration in the arcuate nucleus was not significantly different between estradiol- and oil-treated animals (data not shown) despite the increase in GS protein levels.

Figure 3.

Estradiol increases the concentration of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus. Animals were ovariectomized and treated with either estradiol or oil vehicle. The arcuate was dissected and processed for HPLC. Data are the mean ± sem. Estradiol significantly increased the concentration of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus (t test, *, P = 0.0365).

Estradiol increases extracellular glutamate in the arcuate nucleus

Estradiol increased the concentration of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus, but there are functionally distinct pools of glutamate in the brain including a neurotransmitter pool, a metabolic pool, a glial pool, and a GABA precursor pool (14). Therefore, it was necessary to determine whether the observed increase in glutamate was reflected in the neurotransmitter pool. Microdialysis was used to compare extracellular glutamate levels in the arcuate nucleus during and after a KCl challenge. KCl depolarizes the neuronal membrane resulting in the release of neurotransmitters from synaptic pools. High concentrations of potassium pumped through the dialysis probe drastically increase the release of glutamate (41). This increase is readily detectable in the dialysate and has been characterized as calcium-dependent (41). Thus, changes in the extracellular glutamate concentrations after KCl administration represent synaptically released glutamate.

Qualitatively an increase in extracellular glutamate after KCl administration was observed in the estradiol-treated animals (Fig. 4A). Total glutamate over the course of the experiment was measured by quantifying the area under the curve for both estradiol- and oil-treated animals. There was approximately a 40% increase in total extracellular glutamate in estradiol-treated animals compared with oil-treated animals (Fig. 4, C and D). This suggests that, overall, extracellular glutamate levels were increased in the arcuate nucleus in response to estradiol.

Figure 4.

Estradiol increases extracellular glutamate in the arcuate nucleus. Microdialysis was used to compare extracellular glutamate levels in the arcuate nucleus during and after a KCl challenge, which will stimulate release of neurotransmitter pools from arcuate neurons. All data are expressed as a percent change from baseline. A, A qualitative increase in extracellular glutamate is observed after KCl inclusion in the perfusate in the estradiol-treated animals. B, Extracellular glutamate concentration is significantly increased in both oil- and estradiol-treated animals after KCl administration (Wilcoxon test, oil, P = 0.0312, estradiol, P = 0.0312). Estradiol significantly increased the concentration of glutamate after KCl compared with oil-treated animals (Mann-Whitney U, *, P = 0.0476). C and D, The total extracellular glutamate in the arcuate over the course of the experiment was measured by taking the area under the curve for both estradiol- and oil-treated animals. Estradiol significantly increased the total extracellular glutamate concentration in the arcuate nucleus (t test, *, P = 0.05). E, Extracellular glutamine also responds to a synaptic challenge. Extracellular glutamine was also measured in the microdialysis studies. The concentration of extracellular glutamine was decreased before the peak in extracellular glutamate during KCl administration. There was no effect of treatment on extracellular glutamine levels.

The extracellular glutamate levels before and after KCl administration were also compared by averaging the five time points before and after KCl for each animal. There was a significant increase in extracellular glutamate after KCl in both oil- and estradiol-treated animals (Fig. 4B). This is to be expected because KCl administration stimulates the release of neurotransmitter and increases extracellular glutamate. More interestingly, the concentration of extracellular glutamate after KCl was increased by 58% in estradiol-treated animals compared with oil-treated animals (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that estradiol increases the availability of glutamate to arcuate nucleus synapses. A possible mechanism for this increase in glutamate availability may be through activity of the glutamate-glutamine cycle.

Glutamine responds to synaptic challenge

The glutamine concentration was also measured during the microdialysis experiment. The concentration of extracellular glutamine was decreased before the appearance of the peak in extracellular glutamate during KCl administration (Fig. 4E). Whereas there was not an effect of estradiol on the extracellular glutamine concentration, the rapid decrease in glutamine before the peak in extracellular glutamate suggests that glutamine may be necessary for the generation and/or maintenance of the glutamate response to KCl and further implicates the glutamate-glutamine cycle enzymes in the increased production of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus. These data suggest that the difference in extracellular glutamate between estradiol- and oil-treated animals may be related to an increased efficiency of the glutamate-glutamine cycle.

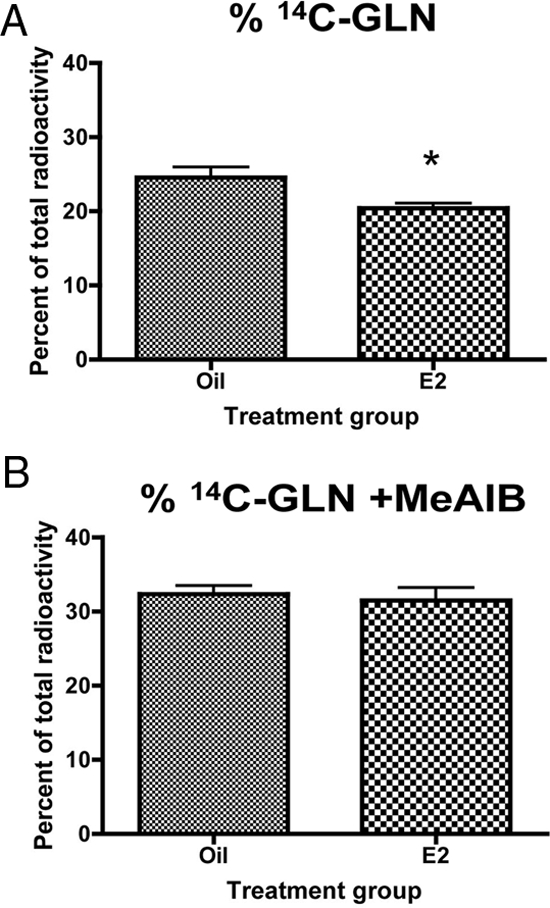

Estradiol decreases the conversion of 14C-GLU to 14C-GLN

The microdialysis data suggest that the difference in extracellular glutamate between estradiol- and oil-treated animals in the arcuate nucleus may be related to a difference in the efficiency of the glutamate-glutamine cycle enzymes. We have shown a significant increase in GS and glutaminase protein levels; however, it is important to determine whether this correlates with an increase in enzyme activity. To this end, we used HPLC paired with liquid scintillation spectroscopy to measure GS activity in vivo. The used of radiolabeled substrates allowed for the direct measurement of GS activity in vivo by calculating the percent of 14C-GLU converted to 14C-GLN. Estradiol decreased the percent of 14C-GLN in the arcuate nucleus by 17% (Fig. 5A). This was an unexpected result, given the significant increase in GS protein. The most parsimonious explanation is that the injected 14C-GLU was converted to GABA instead of entering the cycle as a substrate for GS. Glutamate is an immediate precursor for GABA. Additionally, estradiol has been shown to increase the expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) 65/67 (the GABA synthesizing enzymes) and GABA synthesis in other hypothalamic nuclei (21,22). However, the percent conversion of 14C-GABA was not significantly different between estradiol- and oil-treated animals (data not shown). This raises the possibility that the increase in enzyme protein does not correlate with an increase in enzyme activity.

Figure 5.

Estradiol decreases the conversion of 14C-GLU to glutamine. GS activity was measured in vivo by calculating the percent conversion of 14C-GLU injected in the arcuate nucleus to glutamine. Data are the mean ± sem. A, Estradiol significantly decreased the percent of 14C-GLN in the arcuate nucleus (t test, *, P = 0.0313). B, Blocking glutamine uptake reverses the effect of estradiol on the conversion of 14C-GLU to 14C-GLU. The decreased conversion of 14C-GLU to glutamine in the presence of estradiol was blocked when MeAIB was injected.

Blocking glutamine uptake reverses the effect of estradiol

Alternatively, glutamate metabolism is a cyclic process that involves both neurons and glial cells. Astrocytic transporters take glutamate into the astrocyte, where GS converts the glutamate to glutamine. This glutamine is then transported back to the neurons by system A transporters. Once inside the neuron, it can be converted by glutaminase into glutamate. Estradiol significantly increased both GS and glutaminase mRNA and protein. Therefore, it is possible that the decrease in 14C-GLN results from the glutamine being rapidly transported back to the neuron and converted to glutamate. When glutamine uptake in the arcuate nucleus was blocked with a specific glutamine transporter inhibitor MeAIB in the presence of 14C-GLU, there was no significant difference in 14C-GLN between estradiol- and oil-treated animals (Fig. 5B). Thus, suggesting that the difference seen in the absence of MeAIB was due to increased glutamine uptake and likely increased glutaminase activity.

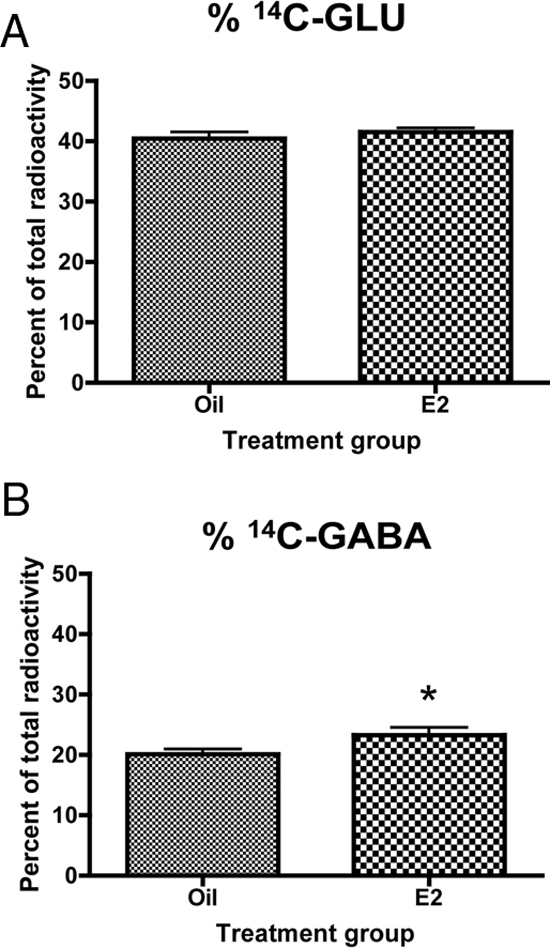

Estradiol increases the conversion of 14C-GLN to 14C-GABA

The above data suggested glutaminase activity may be the key factor in regulating glutamate levels in the arcuate. Therefore, glutaminase activity was measured in vivo by injecting animals with 14C-GLN and measuring the percent conversion to glutamate and GABA. Estradiol had no significant effect on the percent of 14C-GLU in the arcuate nucleus (Fig. 6A). However, estradiol did increase the percent of 14C-GABA in the arcuate nucleus by 16% (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Estradiol increases the conversion of 14C-GLN to GABA. Glutaminase activity was measured in vivo by calculating the percent conversion of 14C-GLN injected into the arcuate nucleus to glutamate. Data are the mean ± sem. A, Estradiol had no significant effect on the percent of 14C-GLU in the arcuate nucleus. B, Estradiol significantly increased the percent of 14C-GABA in the arcuate (t test, *, P = 0.0261).

Discussion

The data presented here suggest that there are two independent effects of estradiol on amino acid neurotransmission in the arcuate nucleus. Estradiol increases glutamatergic neurotransmission in the arcuate nucleus by a mechanism that is independent of its effects on the glutamate-glutamine cycle. Estradiol does affect the glutamate-glutamine cycle, but it seems to be more important for the production of GABA rather than glutamate (supplemental Fig. 3).

This is consistent with reports of the importance of glutamine to GABA neurotransmission. GABAergic neurons contain all the necessary machinery for the metabolism of glutamine. System N transporters (those that transport glutamine from the astrocyte into the extracellular space) are associated with GABAergic synapses in a range of brain regions (23) and system A transporters (those responsible for glutamine uptake into neurons) are present on both excitatory and inhibitory neurons (24). There is also some evidence to suggest that there is colocalization of GAD65/67 and glutaminase is certain brain regions (25,26,27). Electrophysiological studies in hippocampal slices have shown that inhibition of the glutamate-glutamine cycle, either by blocking glutaminase uptake or GS activity affects evoked inhibitory post-synaptic current amplitude after burst stimulation, suggesting that the glutamate-glutamine cycle is important to the maintenance of synaptic GABA release (28). A separate electrophysiological study observed that neurons can maintain glutamate neurotransmission independent of the glutamate-glutamine cycle for extended periods of time (29). Taken together, these electrophysiological studies support the hypothesis that the glutamate-glutamine cycle is more important for GABAergic neurotransmission than glutamatergic neurotransmission.

However, most studies implicating glutamine in GABA production report that this glutamine comes from astrocytic GS (7,24,28). This is contrary to the results reported here. When 14C-GLU is injected, there is no effect of estradiol on GABA production, which would be expected if the glutamine required for GABA synthesis were coming from astrocytic GS. However, when 14C-GLN is injected into the arcuate nucleus, there is a significant increase in GABA production. This may be explained because the fate of glutamate or glutamine often depends on their concentrations. It has been reported that adding glutamine stimulates GABA synthesis in cortical synaptosomes in a concentration-dependent manner (30). It is possible that the amount of glutamine generated when 14C-GLU is injected into the arcuate nucleus is not enough to stimulate GABA production. In addition, as the concentration of extracellular glutamate rises, it is more likely to be metabolized in the tricarboxylic acid cycle than by GS (31). Therefore, one of the reasons there is no effect of estradiol on GABA production when 14C-GLU is injected may be because the majority of the glutamate is being converted to lactate and aspartate via the trichloroacetic acid cycle rather than to glutamine and the small amount that is being converted to glutamine is preferentially shuttled to glutamatergic neurons. When 14C-GLN is added to the endogenous extracellular glutamine pools, the shift in concentration may be enough to stimulate GABA production and reveal the difference between estradiol- and oil-treated animals. This is further supported by reports that estradiol has been shown to modulate the mRNA for GAD65/67 (22) and in a developmental model increases GABA concentration (21).

Estradiol also increased the concentration of glutamate in the arcuate nucleus. This effect was significant, albeit small in magnitude. However, it is important to consider that at the cellular level, quantitatively small changes in glutamatergic neurotransmission may be amplified by the induction of biologically significant signaling cascades leading to changes in cellular function. In addition, our results are consistent with previous reports that estradiol can modulate glutamatergic neurotransmission in various brain regions (32,33,34) and that it increases excitability in the arcuate specifically (4,35). Our results show a significant increase in extracellular glutamate levels over the course of the experiment, suggesting that estradiol causes a significant change in glutamatergic signaling that is amplified after stimulation. Although the increases in glutamate-glutamine cycle enzymes do not seem to be important for the increase in extracellular glutamate, it is possible that this increase is the result of a presynaptic change in glutamate release. Estradiol has been shown to increase glutamate release in cultured hippocampal and VMN neurons (33,36). In the case of the VMN, this increase in presynaptic glutamate release leads to an increase in dendritic spines (36). Estradiol can also modulate synaptic morphology in the arcuate nucleus by increasing the number of axospinous synapses (4).

Estradiol is a potent inhibitor of feeding in rodents; however, the mechanism of this action is largely unknown (37). The generally accepted theory is that estradiol is acting centrally to affect food intake (37). Leptin, a peripheral signal that reflects body fat storage and is known to regulate food intake and body weight, causes a rewiring of arcuate synapses that increases the number of inhibitory inputs to orexigenic neuropeptide Y neurons and the number of excitatory inputs to anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons (38). Interestingly, it has been shown that estradiol can mimic leptin in the arcuate nucleus by altering excitatory inputs to POMC neurons and decreasing food intake and body weight (39). Estradiol also increases the number of c-Fos expressing POMC neurons in the arcuate nucleus and the number of miniature excitatory postsynaptic current compared with controls (39). Our observed increase in extracellular glutamate levels in the arcuate nucleus in the presence of estradiol suggests that there is increased glutamatergic innervation of the arcuate nucleus in the presence of estradiol that may be contributing to its anorexigenic effects.

Similarly, POMC neurons have been shown to be able to release GABA, but it seems that this is not important for reciprocal signaling onto neuropeptide Y neurons but rather is important for mediating rapid inhibitory inputs on extrahypothalamic targets (40). Our results have shown an estradiol-mediated increase in the production of GABA, supporting the possibility that it is a downstream mediator of an anorexigenic feeding circuit.

We hypothesize, based on the data presented here as well as the literature on amino acid metabolism, neuroendocrine processes, and feeding and energy metabolism, that a possible mechanism by which estradiol decreases food intake in female rodents may be by modulating glutamate neurotransmission and GABA production in the hypothalamus. Furthermore, these data reveal a possible functional consequence of the observed changes in glial morphology in the arcuate nucleus in the presence of estradiol and suggest the importance of neuronal-glial cooperation in the regulation of important hypothalamic functions. Future experiments will test the hypothesis that the glutamate-glutamine cycle plays a role in mediating the anorexigenic effects of estradiol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Benham for her assistance on the immunocytochemistry experiments and Dr. Ingeborg Aasland Torgner for the glutaminase antibody.

Footnotes

This work was supported by predoctoral National Research Service Award NS059166 (to T.B.); Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Award K12HD43489 (to J.A.M.); and Grants HL85037 (to J.A.M.) and HD16596 (to H.R.Z.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 19, 2009

Abbreviations: aCSF, Artificial cerebral spinal fluid; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GAD, glutamic acid decarboxylase; 14C-GLN, 14C-glutamine; 14C-GLU, 14C-glutamate; MeAIB, methylaminoisobutyric acid; GS, glutamine synthetase; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; T-TBS, Tris-buffered saline solution with Tween 20; VMN, ventromedial nucleus.

References

- Garcia-Segura LM, Chowen JA, Naftolin F 1996 Endocrine glia: roles of glial cells in the brain actions of steroid and thyroid hormones and in the regulation of hormone secretion. Front Neuroendocrinol 17:180–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L, Zielke HR 2004 Astrocytic control of glutamatergic activity: astrocytes as stars of the show. Trends Neurosci 27:735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintsova A, Levy WB, Desmond NL 1995 Astrocytic volume fluctuates in the hippocampal CA1 region across the estrous cycle. Brain Res 690:269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parducz A, Hoyk Z, Kis Z, Garcia-Segura LM 2002 Hormonal enhancement of neuronal firing is linked to structural remodelling of excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Eur J Neurosci 16:665–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mong JA, Glaser E, McCarthy MM 1999 Gonadal steroids promote glial differentiation and alter neuronal morphology in the developing hypothalamus in a regionally specific manner. J Neurosci 19:1464–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blutstein T, Devidze N, Choleris E, Jasnow AM, Pfaff DW, Mong JA 2006 Oestradiol up-regulates glutamine synthetase mRNA and protein expression in the hypothalamus and hippocampus: implications for a role of hormonally responsive glia in amino acid neurotransmission. J Neuroendocrinol 18:692–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnewald U, Westergaard N, Schousboe A, Svendsen JS, Unsgård G, Petersen SB 1993 Direct demonstration by [13C]NMR spectroscopy that glutamine from astrocytes is a precursor for GABA synthesis in neurons. Neurochem Int 22:19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD, Martinez-Hernandez A 1979 Fine structural localization of glutamine synthetase in astrocytes of rat brain. Brain Res 161:303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laake JH, Takumi Y, Eidet J, Torgner IA, Roberg B, Kvamme E, Ottersen OP 1999 Postembedding immunogold labelling reveals subcellular localization and pathway-specific enrichment of phosphate activated glutaminase in rat cerebellum. Neuroscience 88:1137–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Espinosa MA, Rodrigues TB, Sierra A, Benito M, Fonseca C, Gray HL, Bartnik BL, García-Martín ML, Ballesteros P, Cerdán S 2004 Cerebral glucose metabolism and the glutamine cycle as detected by in vivo and in vitro 13C NMR spectroscopy. Neurochem Int 45:297–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laake JH, Slyngstad TA, Haug FM, Ottersen OP 1995 Glutamine from glial cells is essential for the maintenance of the nerve terminal pool of glutamate: immunogold evidence from hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurochem 65:871–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, McCarthy MM 2004 Minireview: role of glia in neuroendocrine function. Endocrinology 145:1082–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, Lorenz B, DonCarlos LL 2008 The role of glia in the hypothalamus: implications for gonadal steroid feedback and reproductive neuroendocrine output. Reproduction 135:419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann DW, Mahesh VB 1997 Excitatory amino acids: evidence for a role in the control of reproduction and anterior pituitary hormone secretion. Endocr Rev 18:678–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjimarkou MM, Benham R, Schwarz JM, Holder MK, Mong JA 2008 Estradiol suppresses rapid eye movement sleep and activation of sleep-active neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic area. Eur J Neurosci 27:1780–1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M, Brownstein M 1988 Maps and guide to microdissection of the rat brain. New York: Elsevier [Google Scholar]

- Shank RP, Leo GC, Zielke HR 1993 Cerebral metabolic compartmentation as revealed by nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of d-[1–13C]glucose metabolism. J Neurochem 61:315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H, Ransom BR, eds. 2005 Neuroglia. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Zielke HR, Zielke CL, Baab PJ 2007 Oxidation of (14)C-labeled compounds perfused by microdialysis in the brains of free-moving rats. J Neurosci Res 85:3145–3149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C 1986 The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Davis AM, Ward SC, Selmanoff M, Herbison AE, McCarthy MM 1999 Developmental sex differences in amino acid neurotransmitter levels in hypothalamic and limbic areas of rat brain. Neuroscience 90:1471–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Kaufman LC, Brooks PJ, Pfaff DW, Schwartz-Giblin S 1995 Estrogen modulation of mRNA levels for the two forms of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in female rat brain. J Comp Neurol 360:685–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulland JL, Osen KK, Levy LM, Danbolt NC, Edwards RH, Storm-Mathisen J, Chaudhry FA 2002 Cell-specific expression of the glutamine transporter SN1 suggests differences in dependence on the glutamine cycle. Eur J Neurosci 15:1615–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke MN, Jones-Davis DM, Mathews GC 2007 Glutamine uptake by System A transporters maintains neurotransmitter GABA synthesis and inhibitory synaptic transmission. J Neurochem 102:1895–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns ID, Mainville L, Jones BE 2001 Evidence for glutamate, in addition to acetylcholine and GABA, neurotransmitter synthesis in basal forebrain neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex. Neuroscience 107:249–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti I, Henny P, Galloni F, Mainville L, Mariotti M, Jones BE 2006 Stereological estimates of the basal forebrain cell population in the rat, including neurons containing choline acetyltransferase, glutamic acid decarboxylase or phosphate-activated glutaminase and colocalizing vesicular glutamate transporters. Neuroscience 143:1051–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS 2007 Co-localization of glutamic acid decarboxylase and phosphate-activated glutaminase in neurons of lateral reticular nucleus in feline thalamus. Neurochem Res 32:177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang SL, Carlson GC, Coulter DA 2006 Dynamic regulation of synaptic GABA release by the glutamate-glutamine cycle in hippocampal area CA1. J Neurosci 26:8537–8548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam K, Nicoll R 2007 Excitatory synaptic transmission persists independently of the glutamate-glutamine cycle. J Neurosci 27:9192–9200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglioli G, Martin DL 1996 Glutamine stimulates gamma-aminobutyric acid synthesis in synaptosomes but other putative astrocyte-to-neuron shuttle substrates do not. Neurosci Lett 209:129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna MC 2007 The glutamate-glutamine cycle is not stoichiometric: fates of glutamate in brain. J Neurosci Res 85:3347–3358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Moss RL 1992 Long-term and short-term electrophysiological effects of estrogen on the synaptic properties of hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Neurosci 12:3217–3225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokomaku D, Numakawa T, Numakawa Y, Suzuki S, Matsumoto T, Adachi N, Nishio C, Taguchi T, Hatanaka H 2003 Estrogen enhances depolarization-induced glutamate release through activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase in cultured hippocampal neurons. Mol Endocrinol 17:831–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SG, Humphreys AG, Juraska JM, Greenough WT 1995 LTP varies across the estrous cycle: enhanced synaptic plasticity in proestrus rats. Brain Res 703:26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kis Z, Horváth S, Hoyk Z, Toldi J, Párducz A 1999 Estrogen effects on arcuate neurons in rat. An in situ electrophysiological study. Neuroreport 10:3649–3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Liang SL, Thompson SM, McCarthy MM 2008 Estradiol induces hypothalamic dendritic spines by enhancing glutamate release: a mechanism for organizational sex differences. Neuron 58:584–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarian L, Geary N 2006 Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361:1251–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto S, Roseberry AG, Liu H, Diano S, Shanabrough M, Cai X, Friedman JM, Horvath TL 2004 Rapid rewiring of arcuate nucleus feeding circuits by leptin. Science 304:110–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Mezei G, Nie Y, Rao Y, Choi CS, Bechmann I, Leranth C, Toran-Allerand D, Priest CA, Roberts JL, Gao XB, Mobbs C, Shulman GI, Diano S, Horvath TL 2007 Anorectic estrogen mimics leptin’s effect on the rewiring of melanocortin cells and Stat3 signaling in obese animals. Nat Med 13:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges ST, Nishiyama M, Overstreet LS, Stenzel-Poore M, Williams JT, Low MJ 2004 GABA release from proopiomelanocortin neurons. J Neurosci 24:1578–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink BHC, Cremers TIFH, eds. 2007 Handbook of microdialysis: methods, and perspectives. New York: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.