Abstract

Ovulation has long been regarded as a process resembling an inflammatory response. Recent studies indicate that genes associated with innate immune responses were also expressed during the ovulation process. Because the innate immune genes are induced in cumulus cell oocyte complexes (COCs) later than the inflammation-associated genes, we hypothesize that COC expansion is dependent on specific sequential changes in cumulus cells. Because IL-6 is a potent mediator of immune responses, we sought to determine what factors regulate the induction of Il6 mRNA in COCs and what impact IL-6 alone would have on COC expansion. We found that the levels of Il6 mRNA increased dramatically during COC expansion, both in vivo and in vitro. Moreover, IL-6, together with its soluble receptor (IL-6SR), could bypass the need for either amphiregulin and/or prostaglandin E2 to induce the expansion of COCs. This ability of IL-6/IL-6SR to induce COC expansion was blocked by the inhibitors to p38MAPK, MAPK kinase 1/2, and Janus kinase. More importantly, when COCs were in vitro maturated in the presence of IL-6, they had a significantly higher embryo transfer rate than the ones without IL-6 and comparable with in vivo matured oocytes. IL-6/IL-6SR activated multiple signaling pathways (Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription, ERK1/2, p38MAPK, and AKT) and progressively induced genes known to impact COC expansion, genes related to inflammation and immune responses, and some transcription factors. Collectively, these data indicate that IL-6 alone can act as a potent autocrine regulator of ovarian cumulus cell function, COC expansion, and oocyte competence.

IL-6 is induced in cumulus cells of ovulating follicles where it can serve as an autocrine regulator of specific genes, COC expansion, and oocyte competence.

Ovulation is essential for reproductive success in all mammals. The ovulation process is initiated by the surge of LH from the pituitary and culminates in the release of a fertilizable oocyte from the surface of the ovary. For this process to be completed, marked changes must occur in the expression of specific genes in granulosa cells (GCs), cumulus cells, and the oocyte (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Although many genes associated with inflammation and the formation of the hyaluronan-rich matrix, such as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2), hyaluronan synthase 2 (Has2), and TNF-α induced protein 6 (Tnfaip6) have been shown to impact ovulation (9,10,11), recent studies indicate that ovulation is not only similar to an inflammatory response but is associated with the induction of many genes in GCs and cumulus cells that have been thought to be specific for immune cells. These include CD34 antigen, CD52 antigen, and the pathogen recognition receptors belonging to the Toll-like receptor family (7,4,13). In addition cumulus cells within the expanded cumulus cell oocyte complex (COC) express elevated levels of the cytokine IL-6 (4) and have been shown secrete not only IL-6 but also potent chemokines [such as chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5), also known as regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES) 5] (14).

The expression of the cytokines in GCs and cumulus cells is regulated in part by paracrine and autocrine regulatory loops, respectively (6,15). During the initiation of ovulation in the mouse, LH via p38MAPK/protein kinase A (PKA) induces epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like factors [amphiregulin (Areg), betacellulin, epiregulin (Ereg)] in GCs that via the EGF-receptor/rat sarcoma viral oncogene (RAS)/ERK1/2 pathway induce PTGS2 leading to prostaglandin (PGE)-2 production. The EGF-like factors and PGE2 released from GCs subsequently activate cumulus cells leading to the expression of Ptgs2, Areg, and Il6 mRNAs, respectively, in these cells (15). The expression of Areg, Ereg, and Il6 mRNAs is reduced in ovaries of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (eCG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) primed progesterone receptor (PGR) knockout mice that fail to ovulate (15,16). Expression of synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (Snap25) mRNA and protein, a key component of secretion vesicles that mediate the release of cytokines from GCs is also reduced in ovaries of eCG-hCG primed PGR knockout mice (14). Thus, regulated expression and release of cytokines appears to be associated with, and may be required for the normal ovulatory process. However, the precise functions of specific cytokines such as IL-6 in the ovary, and more specifically in ovulatory follicles, remain ill defined.

The IL-6 family contains several members, including leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M (OSM), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), IL-11, and cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1 (CLCF1) (17,18). They share the common receptor IL-6 signal transducer (IL-6ST, also known as gp130) and have overlapping biological functions (17). LIF has been implicated in early follicle formation (19), oocyte quality (20), and implantation (21,22), indicating that this member of the family can impact reproduction. Mice with a conditional knockout of the gp130 receptor in oocytes exhibit impaired zygotic cleavage to the two-cell stage (23), indicating that oocytes can be direct targets of cytokine action. Because signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3 has been shown to be present in oocytes (24), STAT3 may be one critical downstream mediator of cytokine action in these cells. However, because Stat3 null mice are embryonic lethal (25), its role in the ovary has not yet been elucidated. Although Il6 null mice appear to be fertile (26,27), Il6 is induced dramatically in COCs during ovulation and therefore may modulate oocyte cumulus cell or oocyte functions (4). Because IL-6, as well as other potent cytokines, are increased in serum and follicular fluid of ovulatory follicles of patients with endometriosis (28,29,30), these inappropriately higher levels may reflect altered follicle/ovarian production of this cytokine and hence altered functions of GCs, cumulus cells, or oocytes in these patients.

Based on these considerations, we hypothesized that LH, AREG, and PGE2 establish a precise pattern of inflammatory and immune-related events that control the normal processes of ovulation and that IL-6 (and related cytokines) may be one critical component controlling this process. Therefore, the studies described herein were undertaken to determine not only what factors regulate the induction of Il6 expression in GCs and cumulus cells of ovulating follicles but what function(s) IL-6 itself might exert in COCs during ovulation. Importantly, we document that IL-6 alone can induce COC expansion and the expression of genes known to be involved in this process. In addition, IL-6 regulates the expression of additional genes. We also document that the presence of IL-6 in in vitro maturation protocols enhances the quality of the oocytes leading to increased fertility.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG/eCG), H89, indomethacin, SB203580 (SB20), U0126, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor I were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Pregnyl (hCG) was from Organon Special Chemicals (West Orange, NJ). Ovine FSH-16 was a generous gift from the National Hormone and Pituitary Agency (Rockville, MD). AREG, IL-6, IL-6 soluble receptor (IL-6SR), OSM, and CNTF were from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). PGE2 was purchased from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI). Routine chemicals and reagents were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) or Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Antibodies for phospho-AKT, phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2), phospho-P38 MAPK, phospho-nuclear factor-κB P65, peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ, STAT3, phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705), phospho-STAT3 (Ser727), and phospho-STAT5) were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Antibody for β-actin was from Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Denver, CO).

Animals

Immature female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Harlan, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). On d 23 of age, female mice were injected ip with 4 IU eCG to stimulate follicular growth followed 48 h later with 5 IU hCG to stimulate ovulation and luteinization (3). Animals were housed under a 16-h light, 8-h dark schedule in the Center for Comparative Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and provided food and water ad libitum. Animals were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine.

Cumulus oocyte complex isolation and expansion in culture:

The procedures used for in vivo COCs isolation and in vitro expansion were described previously (4). Briefly, COC cells and GCs were released from preovulatory follicles into the culture medium by needle puncture of the ovary. The COCs were collected separately from the GCs by pipette, pooled, and treated as described in the following details.

For analyses of in vivo gene expression patterns, COCs were isolated from ovaries of immature mice primed with eCG for 48 h, or eCG-primed mice exposed to hCG for 2, 4, 8, 12, or 16 h. The COCs from at least five mice were pooled and stored at −80 C until RNA extraction. GCs at the corresponding time points were also collected. The experiments were repeated twice.

For in vitro COC expansion, nonexpanded COCs (∼15) from eCG-primed immature mice were plated in separate wells of a Nunclon 4-well plate (Sigma) in 50 μl of defined COC medium (MEM, 25 mm HEPES, 0.25 mm sodium pyruvate, 3 mm l-glutamine, 1 mg/ml BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) (31) with 1% fetal bovine serum under the cover of mineral oil treated with or without different reagents as indicated in the text. Expansion was assessed by microscopic examination after overnight culture.

For in vitro COC gene expression analyses, nonexpanded COCs (∼50) were cultured in 500 μl COC medium with 1% fetal bovine serum in the four-well plate. The COCs were treated for 4, 8, or 16 h as explained in the text. Duplicate samples were pooled and stored at −80 C until RNA extraction.

To assess IL-6 activation of downstream signaling pathways, nonexpanded COCs (∼50) were cultured in 500 μl COC medium without serum in the four-well plate and incubated 1 h with selected inhibitors before IL-6/IL-6SR (250 ng/ml) or AREG (100 ng/ml) was added. After 15 min COCs were collected and stored at −80 C until cell lysates were prepared for Western blot analyses.

Bioplex protein array system

IL-6 present in the media of cultured COCs was analyzed with the ELISA-based bioplex protein array system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using Bio-Plex Mouse Cytokine 23-Plex panel.

In vitro maturation, fertilization, blastocyst culture, and embryo transfer

The procedures for in vitro maturation, fertilization, blastocyst culture, and embryo transfer were as described previously (20). Specifically, COCs from eCG-primed immature mice were maturated in vitro in standard in vitro maturation medium (α-MEM, 10% fetal calf serum, 0.2 IU/ml recombinant human FSH and 1.5 IU/ml hCG) with or without 2 μg/ml IL-6, a dose chosen based on previous studies done with LIF (20). Oocytes collected from in vitro expanded COCs, together with a control group of oocytes matured in vivo and collected from the oviducts of mice 16 h after hCG, were processed for in vitro fertilization, blastocyst culture, and embryo transfer. The number of two-cell embryos, blastocysts, and live pups was recorded. The entire experimental paradigm was repeated independently six times.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN Sciences, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacture’s instructions. Total RNA was reverse transcribed using 500 ng poly-dT (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Newark, NJ) and 0.25 U avian myeloblastosis virus-reverse transcriptase (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) at 42 C for 75 min and 95 C for 5 min. The real-time PCR was performed using the Rotor-Gene 3000 thermocycler (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia). The PCR program is as follows: 94 C 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 C 15 sec, 60 C 30 sec, and 72 C 30 sec, with the final extension at 72 C for 5 min followed by a melting curve analysis (from 70 to 95 C). The PCR included 5 μl of SYBR Green JumpStart Taq mix (Sigma), 4.0 μl of cDNA product (1:5 dilution), and 1.0 μl of 2 μm forward and reverse primers (supplemental Table 1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). The primers were as previously described (Pdcd1, Runx1, Runx2) (4) or were designed using software Primer3 (32). Relative levels of gene expression were calculated using Rotor-Gene 6.0 software (Corbett Research) and normalized to levels of ribosomal protein L19 mRNA.

Western blot analyses

COCs and GCs were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate] containing complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Nutley, NJ). Western blots were performed using 100 COCs and equal protein amount of GC lysates.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescent analyses were done as described previously (14) with the antibodies specified in the text. Digital images were captured using a AxioPlan2 microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with × 5–40 objectives in the integrated microscopy core.

Statistics

Differences among groups were analyzed by ANOVA after Tukey-Kramer all-pair comparisons. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Data shown were mean ± sem.

Results

Il6 is up-regulated during ovulation/COC expansion in vivo

To determine the precise temporal pattern of Il6 expression during ovulation in vivo, total RNA was prepared from GCs and COCs isolated from ovaries of immature mice treated with eCG to stimulate the formation of preovulatory follicles followed by hCG to initiate ovulation. Levels of Il6 mRNA were increased in GCs and COCs within 4 h and reached a maximal level at 12 h, just before ovulation (Fig. 1, A and B). This pattern is distinct from that of matrix-related genes such as Has2, shown as a schematic line (Fig. 1B). Although Il6 mRNA levels decline in the luteinizing GCs that remain in the ovary and in ovulated COCs present in the oviduct at 16 h, the levels in each cell type are elevated above the initial baseline (Fig. 1, A and B). The level of IL-6 receptor-α increased slightly after hCG treatment (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Il6 is up-regulated during ovulation/COC expansion in vivo. A, The expression patterns of Il6 and Il6rα in GCs were measured by real-time RT-PCR during ovulation in vivo. Il6 was dramatically induced by hCG, whereas Il6rα was not. B, The expression patterns of Il6, Il6st, Stat3, Cntf, Pparg, and Socs1 in COCs during ovulation in vivo. The dashed line in Il6-chart indicates the relative changes of Has2. Il6 was dramatically increased 4 h after hCG treatment, peaking at hCG12 h, whereas Has2 was peaked at hCG 4 h. The up-regulation of Il6 was associated with an increase of Il6st and Stat3 and a decrease of Pparg and Socs1. All the values are expressed as relative amount to L19. C, Immunofluorescence studies demonstrated that STAT3 staining was intense in oocytes and cumulus cells of preovulatory follicles (a–c), whereas the staining of PPARγ appeared to decrease (h and i) after hCG treatment in a pattern similar to the changes in mRNA. STAT3 staining was also intense in oocytes of primordial follicles (d). The immunostaining of IL-6ST (gp130, red) was also intense in oocytes of preovulatory follicles (e–g). Cg is the zoom-in image of Cf, showing the specific localization of IL-6ST in cumulus cells and oocyte. The insert (Ca) represents the negative controls. In A and B, different letters indicate statistically different groups (P < 0.05).

Because the IL-6 family of cytokines [IL-6, IL-11, OSM, cardiotropin 1 (CTF)-1, CLCF1, and LIF] share the common receptor IL-6ST/gp130, they are presumed to exert some redundant functions. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of the Il6-family members in the same in vivo RNA samples and show that the levels of mRNA encoding three of these (Il11, Osm, and Lif) were too low to be accurately quantified (data not shown). Clcf1 was detectable and peaked after hCG 4 h whereas Ctf1 peaked at hCG16 h and showed about a 2.5-fold increase compared with hCG0 h (data not shown). Cntf mRNA levels remained constant in the collected COCs during the ovulatory period (Fig. 1B). Similar expression patterns were observed in GCs (data not shown). Thus, Il6 appears to be the only factor in the family whose expression increases dramatically in GCs and COCs during the ovulation process after hCG treatment.

Interestingly, the up-regulation of Il6 mRNA is associated with an increase in components of the IL-6 signaling pathway, namely Il6st and Stat3. Levels of Stat3 mRNA peaked in COCs isolated at hCG 4 h (Fig. 1B), and this is associated with intense immunofluorescent staining of STAT3 in GCs and cumulus cells present in ovulatory follicles of ovaries obtained at the same time interval compared with hCG 0 h (Fig. 1, Ca and Cb). Immunostaining of STAT3 in cumulus cells also remained intense at hCG8 h (Fig. 1Cc). The intense immunostaining of STAT3 in oocytes of primordial follicles and ovulatory follicles should also be noted (Fig. 1, Cd and Cc). The expression pattern of Il6st mRNA resembled that of Stat3 and intense immunostaining of IL-6ST was observed in cumulus cells and oocytes of ovulatory follicles (Fig. 1, B and Ce, Cf, and Cg), thereby indicating that oocytes as well as somatic cells have the potential to respond to this cytokine signaling pathway.

PPARγ has been shown to inhibit Il6 expression in many cell types (33,34), and suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1 is a negative regulator of the JAK/STAT pathway (35). Therefore, we sought to determine the expression of these negative regulatory signaling molecules. Whereas Il6 mRNA was up-regulated in COCs from 4 to 12 h after hCG treatment, both Pparγ and Socs1 mRNAs were down-regulated in the same RNA samples (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence analyses of PPARγ confirmed this altered pattern of expression in cumulus cells (Fig. 1, Ch and Ci). Thus, up-regulation of Il6 mRNA after hCG treatment is associated with down-regulation of Pparγ and Socs1.

Il6 is up-regulated during in vitro COC expansion

We next sought to determine whether Il6 mRNA could be induced during COC expansion in vitro and, if so, which hormones and signaling cascades were critical. Nonexpanded COCs were cultured in defined medium with various factors known to induce COC expansion, AREG (100 ng/ml), FSH (100 ng/ml), and PGE2 (1 μm) without or with inhibitors of specific signaling pathways. As shown, Il-6 mRNA was induced by each ligand within 4 h and this response was blocked by inhibitors of p38MAPK (SB20, 10 μm), MAPK kinase (MEK) 1/2 (U0126, 10 μm), and PKA (H89, 10 μm) (Fig. 2A). These results are consistent with the critical roles for activator protein-1 (AP1) and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in regulating the Il6 promoter in other cells (36). The expression of Il6 mRNA was also blocked by indomethacin in COCs cultured with AREG or FSH but not PGE2 (Fig. 2A), indicating that Il6 is a downstream target of PGE2.

Figure 2.

Expression of Il6 mRNA and IL-6 protein in cultured COCs. A, Il6 mRNA was induced by AREG (100 ng/ml), FSH (100 ng/ml), and PGE2 (1 μg/ml) within 4 h, and this response was blocked by inhibitors of p38MAPK (SB20, 10 μm), MEK1/2 (U0126, 10 μm), and PKA (H89, 10 μm). Indomethacin (Indo, 10 μm) also blocked the induction of Il6 by FSH and AREG but not PGE2. B, The induction of Il6 mRNA was blocked by the progesterone antagonist RU486 (10 μm), but levels of Pgr mRNA were not affected. AREG, FSH, and PGE2 induced Il6 and Pgr mRNA to similar levels. Therefore, AREG was used as a representative. C, IL6 protein levels were significantly increased in cultured COCs treated with AREG or FSH for 16 h compared with the control groups (P < 0.001). Different letters indicate statistically different groups (P < 0.05).

RU486, a progesterone receptor antagonist, also blocked the induction of Il6 mRNA by FSH/AREG/PGE2 (Fig. 2B). However, the induction of Pgr mRNA itself was not affected (Fig. 2B), supporting the notion that the progesterone receptor modulates the expression of IL-6 in preovulatory follicles (16).

The induction of Il6 mRNA was associated with increased synthesis and release of IL-6 protein from cultured COCs into the culture medium: AREG (214.63 ± 37.15 pg/ml) and FSH (170.55 ± 35.66 pg/ml) compared with the control groups (4.38 ± 3.76 pg/ml) (P < 0.001) for 16 h (Fig. 2C).

IL-6 induces the expansion of COCs

To determine whether IL-6 could bypass the need for FSH, AREG, or PGE2 and directly induce COC expansion by itself, COCs were cultured with increasing doses (100, 250, and 1000 ng/ml) of IL-6 plus the IL-6SR (used at the same concentration as IL-6 when the two were applied). As shown, IL-6/IL-6SR mediated expansion at each dose tested (Fig. 3A and data not shown) and the degree of COC expansion was comparable with that mediated by AREG (100 ng/ml) or FSH (100 ng/ml) (Fig. 3A and data not shown). IL-6 alone also induced the expansion of COCs to the degree comparable with the effect of AREG, but a higher concentration of the cytokine was needed (data not shown). IL-6SR alone failed to induce the expansion of COCs at any concentrations (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that IL-6 can bypass the need for AREG and/or PGE2 or FSH.

Figure 3.

IL-6/IL-6SR causes expansion of COCs and increase the GVBD rate and the embryo transfer rate. A, Nonexpanded COCs collected from eCG-primed mice were cultured in defined media with agonists and inhibitors as indicated. IL-6/IL-6ST (100 ng/ml, 250 ng/ml and 1 μg/ml) induced the expansion of COCs in a dose-dependent manner (only the later two are shown). The effects at the two higher doses were comparable with AREG (100 ng/ml) whereas IL-6SR (2 μg/ml) alone failed to do so. The ability of IL-6/IL-6SR (250 ng/ml) to induce COC expansion was blocked by the inhibitors to p38MAPK (SB20), MEK1/2 (U0126), and JAK (JAK Inh., which inhibits JAK1/2/3). OSM (2 μg/ml) also partially induced the expansion of COCs. B, When COCs were cultured in HX-saturated medium to block spontaneous GVBD, IL-6/IL-6SR stimulated GVBD as well as FSH, a response significantly higher than that of controls (P < 0.01). C, The presence of IL-6 in the medium of in vitro-matured COCs and oocytes significantly increased the percentage of total live births, to a level comparable with that observed with the in vivo-matured oocytes (IVO) (P > 0.05). Total number of transferred embryos is expressed in each column. Different letters indicate statistically different groups (P < 0.05).

IL-6/IL-6SR binds to the IL-6ST to activate both the JAK/STAT and the ERK1/2 pathways (37). Therefore, inhibitors of these pathways as well as p38MAPK were tested. IL-6/IL-6SR-induced COC expansion was blocked by the inhibitors to p38MAPK (SB20), MEK1/2 (U0126), and JAK (JAK inhibitor, which inhibits JAK1/2/3).

Because LIF induced the expansion of COCs (20), we tested whether other members of the family were affective this assay. Interestingly, whereas OSM partially induced the expansion of COCs at 2 μg/ml (a concentration at which IL-6 alone induced the full expansion of COCs), CNTF, whose expression was not changed after hCG treatment (Fig. 1B), failed to do so at the same concentration (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Thus, some but not all IL-6 family members induce COC expansion under the culture condition with 1% serum in the medium. This is worth noting because when the serum level in the medium was increased to 10%, all the cytokines tested (including IL-11, OSM, CTF1) can induce full COC expansion (data not shown).

IL-6 increases germinal vesicle breakdown

Because AREG, FSH, and PGE2 not only induce COC expansion but also initiate oocyte maturation and germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), we sought to determine whether IL-6/IL-6SR would mimic these effects as well. Nonexpanded COCs were cultured in hypoxanthine (HX)-saturated medium (to block spontaneous maturation) and cultured in the HX media with or without IL-6/IL-6SR (250 ng/ml) or FSH (100 ng/ml). IL-6/IL-6SR was as effective in stimulating GVBD (90 ± 5%) as FSH (90 ± 5%), a response significantly higher than that of controls (30 ± 5%; P < 0.01; Fig. 3B). However, neither IL-6/IL-6SR (250 ng/ml) nor FSH (100 ng/ml) induced denuded oocytes to undergo GVBD, indicating that IL-6 is not the direct factor from cumulus cells to stimulate oocyte GVBD.

IL-6 increases the number of pups born

To test further the effect of IL-6 on COC functions and oocyte quality, nonexpanded COCs were in vitro maturated in the presence or absence of IL-6 (2 μg/ml). These in vitro maturated COCs were then fertilized, the resulting embryos cultured to the blastocyst stage and transferred to recipient, surrogate females, as described in Materials and Methods. Although IL-6 showed no effect on the in vitro fertilization rate or the number of blastocysts obtained, it did significantly increase the success of embryo transfer (26 ± 4 vs. 13 ± 2%; P < 0.04), to a level comparable with that observed with the in vivo matured oocytes (21 ± 3%; P > 0.05; Fig. 3C).

IL-6 activates multiple signal pathways and induces the expression of target genes

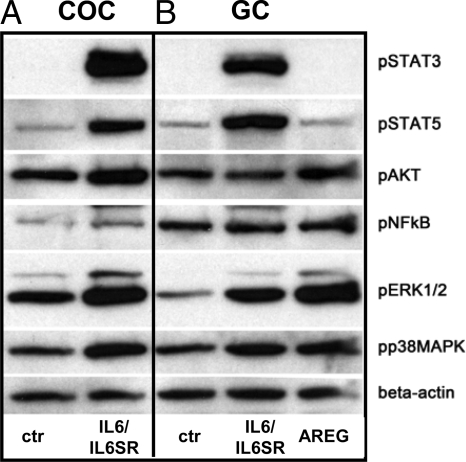

We have shown that the IL-6/IL-6SR-induced expansion of COCs was blocked by the inhibitors of p38MAPK, ERK1/2, and JAK/STAT signaling pathways. Therefore, to determine whether IL-6 activated these signaling pathways in COCs, nonexpanded COCs were cultured in serum-free medium for 1 h before treatment with IL-6/IL-6SR. As shown, IL-6/IL-6SR increased the phosphorylation of JAK targets, STAT3 and STAT5, the MEK target ERK1/2, p38MAPK, and AKT within 15 min (Fig. 4). These data document that IL-6 can activate rapidly multiple signaling cascades in cumulus cells. By contrast, AREG induced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38MAPK, and AKT but did not increase demonstrably the phosphorylation of either STAT3 or STAT5 (Fig. 4). Nuclear factor-κB was not phosphorylated in response to IL-6 or AREG at this time interval.

Figure 4.

IL-6/IL-6SR activates multiple signaling pathways. COCs (A) and GCs (B) from immature mice primed with eCG were isolated in serum-free medium, incubated for 1 h, and treated with or without IL-6/IL-6SR (250 ng/ml) or AREG (100 ng/ml) for 15 min. One hundred COCs were used for each sample treatment. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results. NFκB, Nuclear factor-κB; p, phosphorylated; ctr, control.

Because IL-6/IL-6SR alone could induce COC expansion and stimulated phosphorylation of key kinase cascades in cumulus cells, we next analyzed which genes were regulated by IL-6/IL-6SR during COC expansion. For this, nonexpanded COCs were cultured in defined COC medium alone or in the presence of IL-6/IL-6SR (250 ng/ml) for 4, 8, and 16 h. As shown in Fig. 5A, IL-6/IL-6SR induced expression of genes known to impact COC expansion, including Has2, Ptgs2, Ptx3, and Tnfaip6. Interestingly, unlike FSH or AREG, which induce the expression of these genes within 4 h (Fig. 5A and data not shown), IL-6/IL-6SR induced the expression at a slower rate, with levels at 8 h higher than those observed at 4 h. On the other hand, IL-6/IL-6SR did not induce the expression of either Areg or Il6 itself (Fig. 5A) but did induce the immune-related genes such as Runx1, Runx2, and Pdcd1 (Fig. 5B). IL-6/IL-6SR also highly induced the expression of IL-6/JAK/STAT pathway factors, Il6st and Stat3, and the negative feedback factor Socs1 (Fig. 5C). In addition, IL-6/IL-6SR up-regulated many transcriptional factors, such as Cebpb, Rip140/Nrip1, and Fosl2 (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that although IL-6/IL-6SR induces COC expansion and genes associated with this process, IL-6/IL-6SR also regulates a set of genes distinct from those controlled by FSH or AREG. That AREG/EREG/ betacellulin (BTC) are not induced indicates clearly that the effects of IL-6 occur independently and likely downstream of the EGF-like factors. The induction of Runx1, Runx2, the IL-6/JAK/STAT pathway genes, and some of the transcription factors by IL-6/IL-6SR are clearly more dramatic than by FSH and indicate that they may play a critical role in mediating specific effects of IL-6/IL-6SR.

Figure 5.

Relative gene expression levels in COCs cultured with either FSH or IL-6 for 4, 8, or 16 h as indicated. A, IL-6/IL-6SR induced expression of genes known to impact COC expansion, including Ptgs2, Has2, Tnfaip6, and Ptx3. The peak induction by IL-6/IL-6SR at 8 h differs from the peak induced by FSH (100 ng/ml) at 4 h. IL-6/IL-6SR induced only minimal expression of Areg or IL-6 itself. On the other hand, IL-6/IL-6SR dramatically and rapidly induced the expression of genes related to immune (Runx1, Runx2, Pdcd1) (B), JAK/STAT pathway (Il6st, Stat3, Socs1) (C), and some transcription factors (Cebpb, Fosl2, Rip140) (D). The expression levels were expressed as relative fold changes compared with control (ctr). Different letters indicate statistically different groups (P < 0.05).

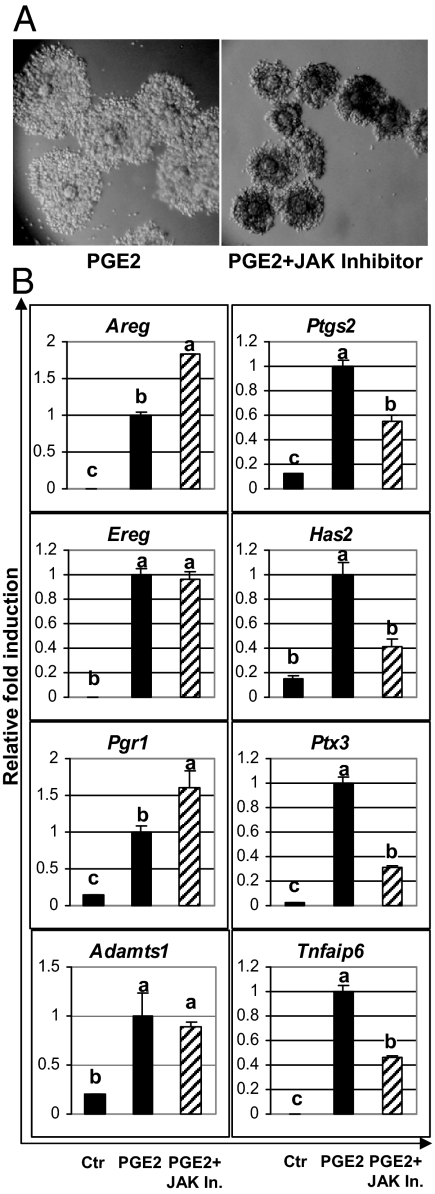

JAK/STAT pathway modulates the expression of key COC expansion genes

Because IL-6 can bypass the requirement of FSH, AREG, or PGE2 to induce the expansion of COC, and this effect was blocked by the JAK inhibitor, we sought to determine whether blocking the JAK/STAT pathway could impair the effects of FSH/AREG/PGE2 on COC expansion. Importantly, COC expansion induced by FSH/AREG/PGE2 was blocked partially by the JAK inhibitor (Fig. 6A and data not shown). To determine which genes were affected by the JAK inhibitor, the COCs were cultured in the presence of PGE2 with or without the JAK inhibitor for 4 h. Whereas genes such as Areg, Ereg, Pgr, and Adamts1 were highly induced by PGE2 and not affected by the JAK inhibitor, the expression levels of Has2, Ptgs2, Tnfaip6, and Ptx3 were reduced about 50% by the JAK inhibitor (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Impact of JAK inhibitor (JAK In.) on COC expansion and gene expression induced by PGE2. A, The expansion of COCs induced by PGE2 (1 μm) was blocked partially by the JAK inhibitor (5 μm). B, COCs were cultured in the presence of PGE2 with or without the JAK inhibitor for 4 h. JAK inhibitor selectively reduced the expression levels of Has2, Ptgs2, Tnfaip6, and Ptx3, whereas it had no inhibitory effect on other genes such as Areg, Ereg, Pgr, and Adamts1. The expression levels were expressed as relative fold changes compared with PGE2-treated samples. Different letters indicate statistically different groups (P < 0.05). ctr, control.

Discussion

These studies document unequivocally, and for the first time, that the potent inflammatory cytokine IL-6 is expressed in, released by, and can act via autocrine regulatory mechanisms in cumulus cells of ovulating follicles. IL-6 acting via IL-6ST/gp130 mediates specific changes in gene expression profiles and COC expansion. Additionally, the production of IL-6 within COCs of ovulating follicles appears to impact oocyte function and quality leading to improved fertility.

The induction of Il6 expression is initiated by the LH surge but is regulated downstream of that by the EGF-like factors and PGE2. Specifically, inhibitors of the ERK1/2, PKA, and p38MAPK block the induction of Il6 mRNA mediated by AREG, FSH, and PGE2. Because there are AP1, CREB, and CAAT enhancer binding protein (CEBP)-β binding sites within the Il6 proximal promoter (36), it is likely that these factors impact the transcriptional regulation of the Il6 gene. However, because the induction of Il6 mRNA in vivo and in cultured COCs occurs much later than that of Areg or Ptgs2 and the rapid increase in CREB phosphorylation, potent negative regulatory factors such as PPARγ (33,34) may also impact Il6 expression because Pparγ mRNA declined dramatically in COCs at a time when Il6 mRNA increased. These results in COCs contrast with those of Kim et al. (16), who reported recently that PPARγ is a target of PGR that is required for the expression of IL-6 in GCs. Although our results confirm that PGR impacts Il6 expression in cumulus cells, the role of PPARγ on Il6 mRNA levels are likely distinct based on the inverse expression patterns of Pparγ and Il6 mRNAs in the COCs. The secretion of IL-6 is also an important PGR-regulated process based on the reduced secretion of this and other cytokines and reduced synaptosomal-associated protein 25 expression in the granulosa/cumulus cells of the Pgr null mice (14).

IL-6 production by cumulus cells appears to be critical because IL-6 alone mediated COC expansion independently of the expression of Areg, Ereg, or Btc mRNAs (Fig. 5A and data not shown). The inability of IL-6 to induce Areg is likely due to its inability to activate PKA and CREB that impact Areg promoter transactivation (39,40). This may also account for the observation that IL-6 did not induce expression of its own gene that contains critical CREB binding sites (36). However, IL-6 did induce genes controlling matrix formation and stability (Has2, Ptx3, Ptgs2, and Tnfaip6) and immune cell related genes (Pdcd1, Runx1, and Runx2) selectively by the JAK pathway. However, the magnitude and temporal pattern of induction of these genes differed from that of FSH and AREG. Whereas levels of Has2 and Ptgs2 at 8 h after IL-6 were similar to those of FSH at 4 h, the levels of Tnfaip6 and Ptx3 at these same time intervals after IL-6 were much lower than those induced by FSH. By contrast, IL-6 was much more potent than FSH in inducing Runx1, Runx2, Nrip1, and Pdcd1. Thus, although the IL-6-induced COC expansion is visibly similar to that induced by AREG, it occurred with reduced expression of key matrix stabilizing factors, Ptgs2, Tnfaip6, and Ptx3. This seems quite remarkable and suggests that runt-related transcription factors (RUNX)-1 and RUNX2 impact specific functions in ovarian cells (41,42) in addition to their impact in osteoblast differentiation and immune cells (43,44). IL-6/IL-6ST induction of other factors including Cebpb and nuclear receptor interacting protein (RIP)-140 (Nrip1), both shown to be critical for COC expansion and ovulation (45,46) as well as the AP1 factors, Fosl2 and Junb, shown to be associated with luteinization (47) may also be important.

IL-6 is a member of the cytokine family that binds to the gp130 receptor/IL-6ST to activate both JAK/STAT and ERK1/2 signaling cascades as indicated by its phosphorylation of STAT3, STAT5, and ERK1/2 in cumulus cells. Moreover, IL-6 induced positive and negative regulatory components of the gp130 pathway, including Stat3, Il6st, Socs1, and Socs3. In addition, IL-6 stimulated the phosphorylation of AKT and p38MAPK, indicating that the gp130 receptor can activate multiple signaling events that mediate IL-6 induction of COC expansion. Because IL-6 induces higher levels of Runx1, Runx2, and Rip140/Nrip1 and because IL-6 but not AREG stimulates the JAK-STAT pathway, it is possible that these transcriptional regulatory factors as well as Pdcd1 are regulated, in part, by the JAK/STAT signaling cascade. Most importantly, the JAK/STAT pathway inhibitors substantially blocked FSH/AREG/PGE2-induced COC expansion and reduced the expression levels of several key expansion-related genes (Ptgs2, Has2, Ptx3, Tnfaip6), thereby documenting that physiologically relevant levels of IL-6 (and other family members) are produced endogenously within these cultured COCs. Therefore, although the levels of IL-6 in the culture medium are less than the concentrations of this cytokine that we used to stimulate COC expansion and gene expression, they reflect the levels associated with a known physiological process. Because IL-6 is acting in the COCs primarily in an autocrine manner, it is likely that the local effective concentration of IL-6 at the cell surface is quite high compared with levels in the culture medium. Moreover, because the EGF-like factors (AREG/EREG/BTC) peak at hCG 2.5 h in vivo whereas IL-6 increases dramatically after hCG 4 h, it is tempting to speculate that IL-6/JAK/STAT pathway acts to help maintain the levels of key matrix genes as well as Runx1, Runx2, Cepbb, and Nrip1 when levels of EGF-like factors decline.

The ability of IL-6 to improve oocyte quality and fertility in in vitro fertilization protocols in mice is of keen clinical interest and potentially important for human in vitro fertilization protocols. The mechanisms by which IL-6 (or other members of the family) mediates this effect are not entirely clear but could be related to activation of STAT3 via gp130/IL-6ST, which are both present in cumulus cells and oocytes of ovulating follicles compared with smaller follicles (24,48). Certainly the role(s) of these cytokines do not appear to be straightforward and many more studies need to be done to resolve the specific vs. redundant functions of each of these factors. Disrupting any one cytokine does not exhibit a major impact in the ovary because disrupting LIF causes an implantation defect (49) and disrupting IL-6 alone also does not appear to impact ovarian function (26,27). However, the disruption of gp130 (Il6st) causes abnormal oocyte-zygotic development, indicating that this pathway is critical during and/or after fertilization (23). Whether this defect is caused by faulty oocyte maturity at an earlier stage of development or a specific event in the oocyte-zygotic stage is not known. Thus, until all cytokines are disrupted, the issue will remain open. However, the potent effects of IL-6/IL-6SR on COC expansion and gene expression profiles that are blocked by the JAK inhibitor clearly indicate that IL-6 can exert potent effects on these cells, and this is relevant to situations in which IL-6 production is normally expressed as well as when it is misregulated. Interestingly, the effects of cytokines mediated by IL-6ST (gp130) are similar to the positive effects of leptin that also appears to enhance oocyte quality via activation of STAT3 (48). Therefore, of further clinical relevance, IL-6 and other cytokines as well as leptin may exert positive effects under normal conditions. However, given their potent effects on cumulus cells and the oocyte, one might predict that if they are elevated within the follicle at inappropriate times or for extended periods of time, such as during chronic infections and in endometriosis and obese patients, negative rather than positive effects could result. Therefore, impaired fertility associated with these conditions could be related to the direct effects of abnormally high and inappropriate levels of IL-6 and other potent cytokines that can alter/impair ovarian follicular cell function, including steroidogenesis and oocyte quality (12,28,29,30,38,50,51,52).

In summary, IL-6 alone can serve as a potent regulator of ovarian cumulus cell function and COC expansion and may mediate some of its effects via activating the ERK1/2, JAK/STAT, and p38MAPK pathways. Its ability to increase oocyte competence not only makes IL-6 a potent factor to be used to increase the in vitro fertilization rate but also provides insights into the functions of COCs and oocyte quality.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD-16229 and U54-HD-007495 (Project III, Specialized Cooperative Program in Reproductive Research.

Disclosure Summary: Z.L., H.-Y.F., M.S., and J.S.R. have nothing to declare. D.G.d.M. and S.P. are employed by EMD Serono Research Institute Inc. and are inventors on U.S. patent WO/2005/054449 (also filed in Australia, Canada, Europe Israel, Japan, and Norway).

First Published Online March 19, 2009

Abbreviations: AP1, Activator protein-1; AREG, amphiregulin; BTC, betacellulin; CEBP, CAAT enhancer binding protein; CLCF1, cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; COC, cell oocyte complex; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; CTF, cardiotropin 1; eCG, pregnant mare serum gonadotropin; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EREG, epiregulin; GC, granulosa cell; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; HX, hypoxanthine; IL-6SR, IL-6 soluble receptor; IL-6ST, IL-6 signal transducer; JAK, Janus kinase; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; MEK, MAPK kinase; OSM, oncostatin M; PGE, prostaglandin E; PGR, progesterone receptor; PKA, protein kinase A; PPAR, peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor; RIP, nuclear receptor interacting protein; RUNX, runt-related transcription factor; SB20, SB203580; SOCS, suppressor of cytokine signaling; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

References

- Espey LL 1980 Ovulation as an inflammatory reaction–a hypothesis. Biol Reprod 22:73–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS 2007 Genetics of ovulation. Semin Reprod Med 25:235–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robker RL, Russell DL, Espey LL, Lydon JP, O'Malley BW, Richards JS 2000 Progesterone-regulated genes in the ovulation process: ADAMTS-1 and cathepsin L proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:4689–4694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Shimada M, Wayne CM, Ochsner SA, White L, Richards JS 2006 Gene expression profiles of cumulus cell oocyte complexes during ovulation reveal cumulus cells express neuronal and immune-related genes: does this expand their role in the ovulation process? Mol Endocrinol 20:1300–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS 2005 Ovulation: new factors that prepare the oocyte for fertilization. Mol Cell Endocrinol 234:75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti M, Hsieh M, Park JY, Su YQ 2006 Role of the EGF network in ovarian follicles. Mol Endocrinol 20:715–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robanya I, Richards JS 2006 Induced expression of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs): novel evidence for innate immune-like cells functions during ovulation. Mol Endocrinol 20:3228–3239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YQ, Sugiura K, Wigglesworth K, O'Brien MJ, Affourtit JP, Pangas SA, Matzuk MM, Eppig JJ 2008 Oocyte regulation of metabolic cooperativity between mouse cumulus cells and oocytes: BMP15 and GDF9 control cholesterol biosynthesis in cumulus cells. Development 135:111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BJ, Lennard DE, Lee CA, Tiano HF, Morham SG, Wetsel WC, Langenbach R 1999 Anovulation in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice is restored by prostaglandin E2 and interleukin-1β. Endocrinology 140:2685–2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fülöp C, Salustri A, Hascall VC 1997 Coding sequence of a hyaluronan synthase homologue expressed during expansion of the mouse cumulus-oocyte complex. Arch Biochem Biophys 337:261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fülöp C, Szántó S, Mukhopadhyay D, Bárdos T, Kamath RV, Rugg MS, Day AJ, Salustri A, Hascall VC, Glant TT, Mikecz K 2003 Impaired cumulus mucification and female sterility in tumor necrosis factor-induced protein-6 deficient mice. Development 130:2253–2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Abreu LG, Romão GS, Dos Reis RM, Ferriani RA, De Sá MF, De Moura MD 2006 Reduced aromatase activity in granulosa cells of women with endometriosis undergoing assisted reproduction techniques. Gynecol Endocrinol 22:432–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Yanai Y, Okazaki T, Noma N, Kawashima I, Mori T, Richards JS 2008 Hyaluronan fragments generated by sperm-secreted hyaluronidase stimulate cytokine/chemokine production via the TLR2 and TLR4 pathway in cumulus cells of ovulated COCs, which may enhance fertilization. Development 135:2001–2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Yanai Y, Okazaki T, Yamashita Y, Sriraman V, Wilson MC, Richards JS 2007 Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 gene expression is hormonally regulated during ovulation and is involved in cytokine/chemokine exocytosis from granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 21:2487–2502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Richards JS 2006 Paracrine and autocrine regulation of epidermal growth factor-like factors in cumulus oocyte complexes and granulosa cells: key role for prostaglandin synthase 2 and progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 20:1352–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Sato M, Li Q, Lydon JP, Demayo FJ, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK 2008 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is a target of progesterone receptor regulation in preovulatory follicles and controls ovulation in mice. Mol Cell Biol 28:1770–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taga T, Kishimoto T 1997 Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol 15:797–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaldi G, Varnum BC, Sarmiento U, Starnes C, Lile J, Scully S, Guo J, Elliott G, McNinch J, Shaklee CL, Freeman D, Manu F, Simonet WS, Boone T, Chang MS 1999 Novel neurotrophin-1/B cell-stimulating factor-3: a cytokine of the IL-6 family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:11458–11463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MK 2005 Regulation of primordial follicle assembly and development. Hum Reprod Update 11:461–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matos DG, Miller K, Scott R, Tran CA, Kagan D, Nataraja SG, Clark A, Palmer S 2008 Leukemia inhibitory factor induces cumulus expansion in immature human and mouse oocytes and improves mouse two-cell rate and delivery rates when it is present during mouse in vitro oocyte maturation. Fertil Steril 90:2367–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ 2007 p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF. Nature 450:721–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CL 2007 Reproduction: the unusual suspect. Nature 450:619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux KA, Schaible K, Wylie C 2003 GP130, the shared receptor for the LIF/IL6 cytokine family in the mouse, is not required for early germ cell differentiation, but is required cell-autonomously in oocytes for ovulation. Development 130:4287–4294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Carvajal L, Medico L, Pepling M 2005 Expression of Stat3 in germ cells of developing and adult mouse ovaries and testes. Gene Expr Patterns 5:475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Noguchi K, Shi W, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Akira S 1997 Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat3 gene leads to early embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:3801–3804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli V, Balena R, Fattori E, Markatos A, Yamamoto M, Tanaka H, Ciliberto G, Rodan GA, Costantini F 1994 Interleukin-6 deficient mice are protected from bone loss caused by estrogen depletion. EMBO J 13:1189–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, Freudenberg M, Lamers M, Kishimoto T, Zinkernagel R, Bluethmann H, Köhler G 1994 Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature 368:339–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez S, Garrido N, Coperias JL, Pardo F, Desco J, García-Velasco JA, Simón C, Pellicer A 2007 Serum interleukin-6 levels are elevated in women with minimal-mild endometriosis. Hum Reprod 22:836–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlberg M, Nejaty J, Fröysa B, Guan Y, Söder O, Bergqvist A 2000 Elevated expression of tumour necrosis factor α in cultured granulosa cells from women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 15:1250–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer A, Albert C, Garrido N, Navarro J, Remohí J, Simón C 2000 The pathophysiology of endometriosis-associated infertility: follicular environment and embryo quality. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 55:109–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner SA, Day AJ, Rugg MS, Breyer RM, Gomer RH, Richards JS 2003 Disrupted function of tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated gene 6 blocks cumulus cell-oocyte complex expansion. Endocrinology 144:4376–4384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H 2000 Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132:365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B 1998 PPAR-γ agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature 391:82–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JH, Kim KH, Kim H 2008 SOCS 3 and PPAR-γ ligands inhibit the expression of IL-6 and TGF-β1 by regulating JAK2/STAT3 signaling in pancreas. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:677–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea JJ, Gadina M, Schreiber RD 2002 Cytokine signaling in 2002: new surprises in the Jak/Stat pathway. Cell 109(Suppl):S121–S131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Brown DA, Kitajima I, Xu X, Heidenreich O, Gryaznov S, Nerenberg M 1996 Binding and functional effects of transcriptional factor Sp1 on the murine interleukin-6 promotor. J Biol Chem 271:7330–7335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S 2000 Roles of STAT3 defined by tissue-specific gene targeting. Oncogene 19:2607–2611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder DM, Mueller MD, Birkhäuser MH, Bersinger NA 2005 Steroids and protein markers in the follicular fluid as indicators of oocyte quality in patients with and without endometriosis. J Assist Reprod Genet 22:257–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Lee SB, Guo H, Evers BM, Sheng H 2003 Prostaglandin E2 stimulates the growth of colon cancer cells via induction of amphiregulin. Cancer Res 63:5218–5223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Evers BM, Sheng H 2004 Prostaglandin E2 synergistically enhances receptor tyrosine kinase-dependent signaling system in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem 279:14287–14293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park ES, Choi S, Muse KN, Curry Jr TE, Jo M 2008 Response gene to complement 32 expression is induced by the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge and regulated by LH-induced mediators in the rodent ovary. Endocrinology 149:3025–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M, Curry Jr TE 2006 Luteinizing hormone-induced RUNX1 regulates the expression of genes in granulosa cells of rat periovulatory follicles. Mol Endocrinol 20:2156–2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JS, Alliston T, Delston R, Derynck R 2005 Repression of Runx2 function by TGF-β through recruitment of class II histone deacetylases by Smad3. EMBO J 24:2543–2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alliston T, Choy L, Ducy P, Karsenty G, Derynck R 2001 TGF-β-induced repression of CBFA1 by Smad3 decreases cbfa1 and osteocalcin expression and inhibits osteoblast differentiation. EMBO J 20:2254–2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterneck E, Tessarollo L, Johnson PF 1997 An essential role for C/EBPβ in female reproduction. Genes Dev 11:2153–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullet JM, Pocock V, Steel JH, White R, Milligan S, Parker MG 2005 Multiple signaling defects in the absence of RIP140 impair both cumulus expansion and follicle rupture. Endocrinology 146:4127–4137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SC, Richards JS 2000 Regulation of AP1 (Jun/Fos) factor expression and activation in ovarian granulosa cells. Relation of JunD and Fra2 to terminal differentiation. J Biol Chem 275:33718–33728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antczak M, Van Blerkom J 1997 Oocyte influences on early development: the regulatory proteins leptin and STAT3 are polarized in mouse and human oocytes and differentially distributed within the cells of the preimplantation stage embryo. Mol Hum Reprod 3:1067–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Köntgen F, Abbondanzo SJ 1992 Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature 359:76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machelon V, Emilie D, Lefevre A, Nome F, Durand-Gasselin I, Testart J 1994 Interleukin-6 biosynthesis in human preovulatory follicles: some of its potential roles at ovulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79:633–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass A, Weiser W, Munafo A, Loumaye E 2001 Leukemia inhibitory factor in human reproduction. Fertil Steril 76:1091–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deura I, Harada T, Taniguchi F, Iwabe T, Izawa M, Terakawa N 2005 Reduction of estrogen production by interleukin-6 in a human granulosa tumor cell line may have implications for endometriosis-associated infertility. Fertil Steril 83(Suppl 1):1086–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.