Abstract

To investigate paracrine regulation of pituitary cell growth, we tested fibroblast growth factor (FGF) regulation of TtT/GF folliculostellate (FS) cells. FGF-2, and FGF-4 markedly induced cell proliferation, evidenced by induction of pituitary tumor transforming gene-1 (Pttg1) mRNA expression and percentage of cells in S phase. Signaling for FGF-2-induced FS cell proliferation was explored by specific pharmacological inhibition. A potent inhibitory effect on FGF-2 action was observed by blocking of Src tyrosine kinase with 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidine (≥0.1 μm), followed by protein kinase C (PKC) inhibition with GF109203X. Treatment with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml; 10 min) activated phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3, ERK, stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase, Akt, and focal adhesion kinase. Src inhibition with 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidine suppressed FGF-2-induced Akt and focal adhesion kinase, indicating effects downstream of FGF-2-induced Src activation. FGF-2 also markedly induced its own mRNA expression, peaking at 2–4 h, and this effect was suppressed by Src tyrosine kinase inhibition. The PKC inhibitor GF109203X abolished FGF-2 autoinduction, indicating PKC as the primary pathway involved in FGF-2 autoregulation in these cells. In addition to pituitary FGF-2 paracrine activity on hormonally active cells, these results show an autofeedback mechanism for FGF-2 in non-hormone-secreting pituitary FS cells, inducing cell growth and its own gene expression, and mediated by Src/PKC signaling.

Targeted inhibition of FGF-2 positive auto-feedback mechanism in established cases of FS cell-dependent pituitary tumors could suppress excess intrapituitary growth factor activity and thus tumor cell growth.

Enigmatic pituitary folliculostellate (FS) cells constitute the major group of nonhormonal cells comprising about 5–10% of the anterior pituitary cell mass (1,2). These cells have a characteristic stellate shape with long cytoplasmic processes and may also form follicle-like cavities containing fluid or colloid material (1,2). Although they do not contain secretory granules and are not active endocrine cells, they form an intrapituitary cell network coupled by gap junctions capable of transmitting intercellular signals in the gland (3). FS cells are considered a major source of intrapituitary growth factors and cytokines, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, follistatin, IL-6, and leukemia inhibitory factor, which regulate the activity of neighboring hormone-secreting pituitary cells in a paracrine manner (2).

Indeed, the pituitary gland is a rich source of growth factors, and both FGF-2 (4,5,6) and VEGF-A (7) were originally isolated from pituitary extracts, and pituitary FS cells are considered the primary cellular source of these factors. FGFs comprise a family of at least 28 structurally related molecules (8) that bind and activate alternatively spliced forms of FGF receptors (FGFR1-4). In the presence of heparin or heparin sulfate proteoglycans, ligand binding leads to receptor dimerization and transphosphorylation. The phosphorylated tyrosine residues act as binding sites for cytosolic proteins and subsequent activation of receptor and cell type-specific intracellular signaling (8).

FGF-2 regulates multiple pituitary hormones (9,10) and is overexpressed and targeted by pituitary transforming gene-1 (PTTG1) in pituitary neoplasia (11). FS cell-derived paracrine FGF-2 is involved in estrogen/TGFβ3 regulation of pituitary lactotroph mitogenesis (12,13,14). In the presence of estrogen, TGFβ3 induces lactotroph cell proliferation only in mixed pituitary cell cultures containing FS cells that respond with FGF-2 up-regulation (12), mediated through a protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent MAPK signaling pathway (13) and increased gap-junctional communication (15). Despite the important role of FS cell-derived FGF-2 in pituitary microenvironment regulation, little is known of autoregulatory effects of FGF-2 on FS cells.

Using established TtT/GF FS cells (16), we report FGF-2 effects on pituitary FS cell proliferation and FGF-2 gene regulation and characterize signaling molecules involved in FGF-2 regulation and action on these hormonally inactive pituitary cells.

Materials and Methods

Materials

DMEM, fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). FGF-basic (FGF-2), VEGF-A, FGF-4, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), IGF-I, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and interferon (IFN) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). GF109203X was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and LY294002, 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidine (PP2) and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor I from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). U0126 was from Promega (Madison, WI).

Cell culture

TtT/GF cells were a generous gift from Dr. Guenter Stalla (Max-Planck Institute for Psychiatry, Munich, Germany) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.4% amphotericin B in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For experiments, cells were plated in 100-mm dishes (∼1.5 × 106 cell density) or six-well plates (∼0.5 × 106 cell density) in complete medium for 24–48 h and synchronized by serum starvation (medium with 0.2% BSA) for a further 24 h. Treatment agents were added with fresh serum-depleted medium and samples collected as indicated. Cell counts were performed with a hemocytometer.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections

TtT/GF cells grown in six-well plates to about 50% confluency were serum starved overnight and transfected with 100 pmol Silencer select negative control no. 1 (Scr) siRNA (catalog no. 4390843), Silencer Select predesigned mouse Akt1 siRNA (catalog no. 4392420; ID s62215), or mouse focal adhesion kinase (FAK; Ptk2) siRNA (catalog no. 4390771; ID s65839; Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX) for 24 h using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After an additional 8 h incubation (serum free medium), treatments were added and samples collected at indicated times.

RT-PCR and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from TtT/GF cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), followed by RNA cleanup and deoxyribonuclease treatment using the RNAeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and cDNA generated using Superscript II (Invitrogen). Two microliters of cDNA were used as a template for PCR to amplify a 465-bp fragment of FGF-2 under the following conditions: 94 C, 2 min, one cycle; 94 C, 50 sec, 58 C, 50 sec, 72 C, 1 min, for 35 cycles; 72 C, 10 min. PCR products were confirmed by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining. The products were gel purified using the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced at Sequetech Corp. (Mountain View, CA).

Templates for probes and Northern blot analysis

RNA extraction was performed using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mouse Pttg1 mRNA expression was detected as described (17). The β-actin probe was a 1.076-kb fragment of the mouse β-actin gene (Ambion). Probe for mouse FGF-2 was generated by PCR, the sequence confirmed as above, and Northern blot performed (17).

Protein extraction, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

After treatments, cells were placed on ice, washed with cold PBS, and lysed in 150 μl (for whole cell extracts) or 1 ml (for immunoprecipitations) modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% NaDodSO4, 0.15M NaCl, 0.01 m sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 2 mm EDTA, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 400 μm sodium orthovanadate], containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4 C and protein concentrations determined by Bradford’s method (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with rabbit polyclonal anti-EGF receptor (EGFR; 3 μg; ab2430; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and preclearing with A/G PLUS-Agarose beads (20 μl; Sigma) overnight at 4 C. IP with appropriate antibody titers was performed for 1 h before addition of A/G PLUS-Agarose beads (20 μl) overnight at 4 C. Immunoprecipitates were washed six times in washing buffer and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (pH 6.8). Western blot analysis was performed according to the guidelines of NuPAGE electrophoresis system protocol (Invitrogen). In brief, cell lysates (∼50 μg protein per lane) were heated for 5 min at 100 C. Proteins were separated on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels and electrotransferred for 1 h to polyvinyl difluoride (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 2% nonfat dry milk (or 5% BSA) in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBS-T) buffer and incubated overnight with primary antibody. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2 (1:800), anti-pTyr (PY99; 1:200), anti-FAK (H-1; 1:200), rabbit polyclonal anti-ERK1/2 (1:800), anti-EGFR (1005; 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit monoclonal anti-pAkt (phospho-S473; 1:1000; Abcam), anti-pFAK (PY397; 1:1000, Invitrogen), rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt, antiglyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, antiphosphorylated stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Thr 183/Tyr 185), antiphosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1 (Tyr 701), anti-pSTAT3 (Ser 727), anti-pSTAT5 (Tyr 694) (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), mouse monoclonal anti-STAT3 (Cell Signaling), and anti-β-actin (1:1000; Sigma). After washing with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1.5 h (2% nonfat dry milk or 5% BSA in TBS-T buffer). Blots were washed and hybridization signals measured by enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ).

Flow cytometric cell cycle analysis

Treatments were added after cell synchronization in fresh serum-depleted medium and samples collected at indicated times. For cell cycle analysis, cells were washed and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol and flow cytometric cell cycle analysis performed as described (17). Cell cycle phases were analyzed by ModFit LT software (version 2.0; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

FGF-2 ELISA

Mouse FGF-2 release in the supernatant of the serum-free culture medium was detected with the use of a human basic FGF ELISA kit (no. ELH-bFGF-001; RayBiotech, Inc., St. Louis, MO). The ability of the assay to detect mouse FGF-2 was confirmed using known mouse FGF-2 (ProSpec, Rehovot, Israel) concentrations in the assay, which revealed a 100% cross-reactivity to mouse FGF-2.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons were evaluated using two-tailed Student’s t test and results expressed as mean ± se of independently performed experiments. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Growth factor-mediated induction of pituitary FS TtT/GF cell proliferation

To assess mitogenic effects of growth factors on TtT/GF pituitary FS cell proliferation, cells were treated with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml), VEGF-A (20 ng/ml), FGF-4 (20 ng/ml), HGF (10 ng/ml), and IGF-I (200 ng/ml) for 24 h and Pttg1 mRNA expression and flow cytometric cell cycle analysis measured (Fig. 1A). Treatment with FGF-2 increased Pttg1 mRNA levels about 3.2-fold and the percentage of cells in S phase about 8.7-fold. FGF-4 and HGF also induced Pttg1 mRNA and S phase entry about 2.4- and 6.5-fold, respectively, whereas VEGF-A and IGF-I did not alter these proliferation markers. Dose-dependent effects of FGF-2 on TtT/GF cell counts at 24 and 72 h are shown in Fig. 1B.

Figure 1.

Growth factor-mediated induction of TtT/GF cell proliferation. TtT/GF cells were serum starved for 24 h and subsequently treated with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml), VEGF-A (20 ng/ml), FGF-4 (20 ng/ml), HGF (10 ng/ml) or IGF-I (200 ng/ml) for 24 h (A) or FGF-2 (B) at indicated doses for 24 and 72 h. A, Total RNA was extracted and Pttg1 mRNA expression determined by Northern blot. Subsequently membranes were stripped and reblotted with a specific probe for β-actin. The ratio of Pttg1 vs. β-actin mRNA was calculated by densitometric analysis of each treatment group. The Pttg1 to β-actin ratio of the control group was set as 1.0 and relative mRNA expression levels normalized (mean ± se; upper panel). Twenty-two hours after growth factor induction, cells were fixed and cell cycle analysis performed by flow cytometry. Percentage of cells in G0/1 phase is depicted by black bars, cells in S phase by white bars, and cells in G2/M phase of the cell cycle by gray bars (lower panel). B, Cell counts (in triplicate) were performed at indicated time points with a ZID coulter counter (three independently performed experiments). Control values were set as 100% and treated groups normalized (mean ± se). ***, P < 0.001.

Signaling molecules involved in FGF-2-mediated TtT/GF cell proliferation

To identify signaling pathways involved in FGF-2-mediated TtT/GF cell proliferation, we blocked key signaling molecules before FGF-2-induced release into the cell cycle. Screening results of pharmacological inhibitors are depicted in Fig. 2A. Blockade of Src tyrosine kinase signaling with PP2 (5 μm) and PKC inhibition with GF109203X (5 μm) abolished FGF-2-induced Pttg1 mRNA expression and S phase induction. Modest inhibitory effects were observed for inhibition of MAPK kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and JAK signaling with U0126 (7.5 μm), LY294002 (7.5 μm), and JAK inhibitor I (5 μm), respectively.

Figure 2.

Signaling molecules involved in FGF-2-mediated TtT/GF cell proliferation. TtT/GF cells were serum starved for 24 h, and treated with U0126, LY294002 (LY; 7.5 μm), GF109203X (GF), PP2, or JAK inhibitor I (5 μm; 1 h) (A) or PP2 (B) at the indicated doses for 1 h before induction with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) for 10 min. Northern blot and cell cycle analyses were performed as for Fig. 1.

Dose-dependent effects of PP2 on FGF-2-induced cell proliferation are shown in Fig. 2B. Both Pttg1 mRNA expression (upper panel) and FGF-2-induced S phase entry (∼10-fold; lower panel) were dose-dependently suppressed by increasing concentrations of PP2 (up to 5 μm).

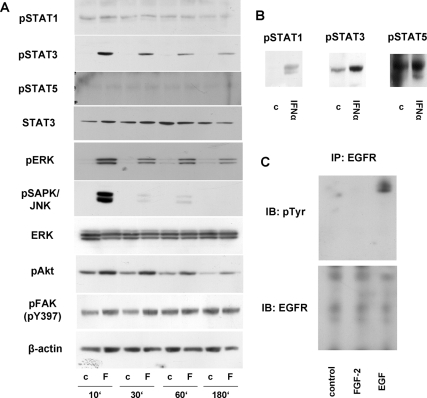

FGF-2 activates FS TtT/GF STAT3, MAPK, and Akt signaling

Time-dependent effects of FGF-2 on key signaling pathways are shown in Fig. 3A. FGF-2 induced rapid (within 10 min) induction of STAT3, ERK, SAPK/JNK, Akt, and FAK phosphorylation, whereas STAT1 and STAT5 phosphorylation were unaltered. Functional STAT protein family expression in these cells was confirmed by demonstrating STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 phosphorylation by IFNα (1000 IU/ml; Fig. 3B). Effects of FGF-2 on SAPK/JNK phosphorylation were transient, peaking at 10 min with a rapid subsequent decline, whereas FGF-induced STAT3, ERK, and Akt phosphorylation were more sustained and persisted for up to 3 h. Interestingly, phosphorylated TtT/GF Akt and FAK levels were also detected at baseline. Given the importance of growth factor induction of EGFR signaling for TtT/GF cell proliferation (17), we also examined effects of FGF-2 on the EGFR (Fig. 3C); however, FGF-2 treatment did not appear to transactivate EGFR in these cells.

Figure 3.

FGF-2-mediated signaling. TtT/GF cells were serum starved overnight and treated with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) for the indicated times (A), IFNα (1000 UI/ml) for 10 min (B), or FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) or EGF (30 ng/ml) for 10 min (C). A and B, pSTAT1, pSTAT3, pSTAT5, total STAT3, pERK1/2, pSAPK/JNK, total ERK1/2, pAkt, pFAK, and β-actin as detected by Western blot of total protein extracts are shown. C, IPs were performed with an EGFR-specific antibody and immunoblotting (IB) with pTyr (PY99; upper panel). Subsequently membranes were stripped and reblotted with EGFR antibody (lower panel). A representative of three independently performed experiments is depicted.

Inhibition of FGF-2-induced signaling by Src tyrosine kinase blockade

To explore the mechanism by which the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 inhibited FGF-2-induced TtT/GF cell proliferation, we tested effects of preincubation with PP2 on FGF-2-mediated signaling induction. As shown in Fig. 4A, Src blockade dose-dependently suppressed FGF-2-induced Akt and FAK phosphorylation but did not alter FGF-2-induced ERK, STAT3, and SAPK/JNK phosphorylation. These results suggest that inhibitory effects of PP2 on FGF-2-induced TtT/GF cell proliferation may be mediated at least in part through suppression of PI3K/Akt and FAK signaling.

Figure 4.

FGF-2 cell signaling inhibition and mRNA regulation. A, TtT/GF cells were serum starved overnight and treated with PP2 at the indicated doses for 1 h before induction with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) for 10 min. pERK1/2, ERK1/2, pAkt, Akt, pSTAT3, STAT3, pSAPK/JNK, pFAK, and β-actin were detected by Western blot of total protein extracts. A representative of three independently performed experiments is depicted. B and C, TtT/GF cells were serum starved overnight and treated with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) for indicated times (B) or PP2 at the indicated doses before induction with FGF-2 for 10 min (C). Total RNA was extracted and FGF-2 mRNA expression determined by Northern blot. Subsequently membranes were stripped and reblotted with a specific probe for β-actin. A representative of two independently performed experiments is depicted.

FGF-2 autoregulation in folliculostellate TtT/GF cells

Given the potent mitogenic effect of FGF-2 on TtT/GF cell proliferation (Fig. 1), we examined whether FGF-2 regulates its own gene expression. Cell number-dependent FGF-2 protein secretion in the cell culture medium was confirmed by ELISA (at 300,000 TtT/GF cells and 24 h detection of ∼300 pg/ml FGF-2; not shown). As shown by Northern blot in Fig. 4B, treatment with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) induced FGF-2 mRNA expression, which peaked at 2–4 h. Pretreatment with PP2 partially suppressed FGF-2-induced FGF-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 4C), suggesting that FGF-2 mRNA autoregulation is mediated at least in part by Src signaling.

Because blockade of Src suppressed FGF-2-induced Akt and FAK (Fig. 4A), we examined involvement of these pathways on autocrine FGF-2-induced FGF-2 mRNA expression. Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K with LY294002 dose-dependently suppressed FGF-2-induced Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 5A), validating the inhibitor activity. However, at the same doses, the inhibitor failed to suppress FGF-2-induced (3 h) FGF-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 5B). In addition, siRNA-mediated Akt and FAK down-regulation (Fig. 5C) both failed to suppress FGF-2 mRNA induction (Fig. 5D), suggesting that these pathways do not signal for FGF-2 autoregulation. In contrast, inhibition of PKC signaling with GF109203X (≥5 μm) abolished FGF-2 induction (Fig. 6A), with no observed effect on FGF-2-induced ERK phosphorylation (up to 10 μm; Fig. 6B), demonstrating specificity of the inhibitor action. Thus, pituitary folliculostellate FGF-2 autoregulation appears to be mediated primarily by PKC signaling.

Figure 5.

Akt and FAK do not mediate FGF-2 mRNA expression. TtT/GF cells were serum starved overnight and treated with LY294002 (A and B) at indicated doses for 1 h before induction with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) for 10 min (A) or 3 h (B). C and D, TtT/GF cells were serum starved overnight, transfected with negative control (Scr), mouse Akt, or FAK (100 pmol) siRNA (24 h). After an additional 8 h (serum free medium), cells were treated with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) for 10 min (C) or 3 h (D). Phosphorylated Akt and FAK, total Akt, and FAK as well as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) loading controls were detected by Western blot in whole-protein extracts (A and C). FGF-2 mRNA expression was detected as in Fig. 4. A representative of two independently performed experiments is shown.

Figure 6.

PKC signals for FGF-2 mRNA expression. TtT/GF cells were serum starved overnight and treated with GF109203X at the indicated doses for 1 h before induction with FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) for 3 h (A) or 10 min (B). FGF-2 mRNA expression was detected as in Fig. 4 (A). Phosphorylated ERK and total ERK were detected by Western blot in whole cell protein extracts (B). A representative of two independently performed experiments is shown.

Discussion

Regulation of pituitary cell growth and hormone secretion is mediated by at least three tiers of control (18). Hypothalamic release and inhibitory factors regulate pituitary trophic cell growth and hormone expression and secretion. Peripheral hormones control respective pituitary function by negative or positive feedback, whereas intrapituitary growth factors regulate trophic hormone cell growth and secretion in an autocrine or paracrine fashion. Pituitary FS cells are an abundant source of growth factors and cytokines, which act in a paracrine manner to target trophic hormone-secreting pituitary cell function (1,2).

The anterior pituitary gland produces abundant amounts of FGF-2. In fact, FGF-2 was originally isolated from pituitary extracts, and the FS cell is considered the primary FGF-2 production source (19). FGF-2 is implicated in the regulation of pituitary hormone secretion in the normal pituitary (9,10), and FGF-2 and FGF receptors are expressed in human pituitary adenomas (20,21), with highest FGF-2 mRNA and blood levels associated with the most aggressive tumors (22). In addition, FGF-2 is targeted by PTTG1, a gene implicated in pituitary cell proliferation and pathogenesis of pituitary tumors (11). PTTG1 overexpression induces FGF-2 mRNA expression in several cell types and cellular coexpression of PTTG1 with its binding factor, PTTG-binding factor, directly regulates FGF-2 transcription (11), suggesting a role for FGF-2 in pituitary tumorigenesis.

In vitro studies have revealed an important role for FS cell-derived FGF-2 in the regulation of 17β-estradiol (E2)/TGF-β3-mediated control of lactotroph cell growth (12,13,23). In addition to direct inhibitory effects of E2 on lactotroph TGF-β1 and TGFβ type II receptor expression and associated loss of growth-inhibitory control, E2 increases lactotroph TGF-β3 release, which induces FGF-2 secretion in neighboring FS cells. Subsequent FS cell-derived FGF-2 stimulates lactotroph proliferation (12,23) through Src-Ras-ERK signaling (24). The mechanism of FS cell FGF-2 regulation by E2/TGF-β3 appears to involve a PKC-dependent ERK signaling pathway (13). These results suggest an important role for locally secreted FGF-2 in pituitary trophic cell growth regulation. Despite the central role of FS cells in pituitary microenvironment regulation, little is known of potential autocrine effects of FGF-2 on FS cell function.

In addition to known mitogenic effects in response to EGF (17), we show here potent induction of cell proliferation in response to FGFs (2 and 4) and HGF in the FS cell line TtT/GF. Although VEGF-A is also secreted by FS cells (7) and locally active IGF-I has been implicated in pituitary GH regulation (25), both growth factors failed to induce cell growth, indicating FGF-2 specificity for FS cell autocrine growth regulation.

Given the cell type specificity and broad spectrum of potential FGFR signaling induction (8), we screened for several FGFR-related pathways (8). Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K, JAK/STAT, MAPK kinase, and PKC signaling suppressed the number of cells entering S phase in response to FGF-2, suggesting that direct or indirect activation of multiple signaling pathways is required for FGF-2-mediated induction of cell proliferation (Fig. 2A); however, the most potent inhibitory effect was achieved with Src blockade.

The nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase, Src, is the archetypal member of a large gene family involved in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, migration, angiogenesis, and immune function (26). Src kinase regulates FGFR activity and signaling (27), and we show here that Src-mediated induction of cell growth in response to FGF-2 appears to involve downstream Akt and FAK signaling because the Src inhibitor PP2 suppressed activation of both pathways in response to FGF-2. Although we did not observe inhibition of peak FGF-2-induced ERK activity by Src blockade, changes in the kinetics of ERK activation and decay, as have been reported in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (27), cannot be excluded.

Induction of FGF-2 mRNA expression by FGF-2 is a novel observation that supports an autofeedback mechanism for FGF-2 in FS cell regulation. Surprisingly, despite the potent antimitogenic effect of Src blockade, inhibition of Src signaling with PP2 only modestly suppressed FGF-2 mRNA induction. In addition, pharmacological and siRNA-mediated suppression of downstream Akt and FAK signaling failed to suppress FGF-2-induced FGF-2 expression, suggesting involvement of alternative signaling molecules in regulation of FGF-2 gene expression. Indeed, pharmacological inhibition of PKC signaling with GF109203X abolished FGF-2-induced FGF-2 mRNA expression, suggesting a central role for PKC signaling in FGF-2 autoregulation, similar to gp130 cytokine regulation in TtT/GF cells (28).

These results support an additional role for pituitary FGF-2 function, i.e. paracrine regulation of hormonally active cells. FS cell-derived FGF-2 may also sustain its own gene expression and enhance FS cell growth in an autocrine fashion. Although isolated cases of human pituitary adenomas composed of FS cells have been reported (29,30,31,32), the role of FS cells in pituitary tumorigenesis still remains unclear. Targeted inhibition of FGF-2-positive autofeedback mechanism in established cases of FS cell-dependent pituitary tumors could suppress excess intrapituitary growth factor activity and thus tumor cell growth.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia Lin (Flow Cytometry Core, Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center).

Footnotes

This work was supported by a scholarship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (VL 55/1-1), National Institutes of Health Grant CA 075979 (to S.M.), and the Doris Factor Molecular Endocrinology Laboratory.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online April 9, 2009

Abbreviations: E2, 17β-Estradiol; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FS, folliculostellate; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IFN, interferon; IP, immunoprecipitation; JAK, Janus kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; p, phosphorylated; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; PP2, 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidine; PTTG1, pituitary tumor-transforming gene-1; SAPK, stress-activated protein kinase; siRNA, small interfering RNA; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TBS-T, Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

- Allaerts W, Vankelecom H 2005 History and perspectives of pituitary folliculo-stellate cell research. Eur J Endocrinol 153:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef C 2008 Paracrinicity: the story of 30 years of cellular pituitary crosstalk. J Neuroendocrinol 20:1–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauquier T, Lacampagne A, Travo P, Bauer K, Mollard P 2002 Hidden face of the anterior pituitary. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:304–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armelin HA 1973 Pituitary extracts and steroid hormones in the control of 3T3 cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70:2702–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gospodarowicz D, Moran JS 1975 Mitogenic effect of fibroblast growth factor on early passage cultures of human and murine fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 66:451–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhlen P, Baird A, Esch F, Ling N, Gospodarowicz D 1984 Isolation and partial molecular characterization of pituitary fibroblast growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81:5364–5368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Henzel WJ 1989 Pituitary follicular cells secrete a novel heparin-binding growth factor specific for vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 161:851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton LM, O'Bryan MK, Hinton BT 2008 Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and their receptors (FGFRs) in male reproduction. Endocr Rev 29:193–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird A, Mormède P, Ying SY, Wehrenberg WB, Ueno N, Ling N, Guillemin R 1985 A nonmitogenic pituitary function of fibroblast growth factor: regulation of thyrotropin and prolactin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:5545–5549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson GH, Koos RD, Sortino MA, Wise PM 1990 Acute effect of basic fibroblast growth factor on secretion of prolactin as assessed by the reverse hemolytic plaque assay. Endocrinology 126:927–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlotides G, Eigler T, Melmed S 2007 Pituitary tumor-transforming gene: physiology and implications for tumorigenesis. Endocr Rev 28:165–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges S, Boyadjieva N, Sarkar DK 2000 Transforming growth factor-β3 stimulates lactotrope cell growth by increasing basic fibroblast growth factor from folliculo-stellate cells. Endocrinology 141:859–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi K, Sarkar DK 2004 Involvement of protein kinase C-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase p44/42 signaling pathway for cross-talk between estradiol and transforming growth factor-β3 in increasing basic fibroblast growth factor in folliculostellate cells. Endocrinology 145:706–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomizu S, Chaturvedi K, Sarkar DK 2004 Folliculostellate cells determine the susceptibility of lactotropes to estradiol’s mitogenic action. Endocrinology 145:1473–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir N, Chaturvedi K, Liu LS, Sarkar DK 2005 Transforming growth factor-β3 increases gap-junctional communication among folliculostellate cells to release basic fibroblast growth factor. Endocrinology 146:4054–4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Matsumoto H, Koyama C, Shibata K, Nakazato Y, Ito A 1992 Establishment of a folliculo-stellate-like cell line from a murine thyrotropic pituitary tumor. Endocrinology 131:3110–3116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlotides G, Cruz-Soto M, Rubinek T, Eigler T, Auernhammer CJ, Melmed S 2006 Mechanisms for growth factor-induced pituitary tumor transforming gene-1 expression in pituitary folliculostellate TtT/GF cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:3321–3335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melmed S 2003 Mechanisms for pituitary tumorigenesis: the plastic pituitary. J Clin Invest 112:1603–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Couch EF, Takano K, Ogawa S 1999 The structure and function of folliculo-stellate cells in the anterior pituitary gland. Arch Histol Cytol 62:205–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzat S, Smyth HS, Ramyar L, Asa SL 1995 Heterogenous in vivo and in vitro expression of basic fibroblast growth factor by human pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:878–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbass SA, Asa SL, Ezzat S 1997 Altered expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors in human pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1160–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzat S, Horvath E, Kovacs K, Smyth HS, Singer W, Asa SL 1995 Basic fibroblast growth factor expression by two prolactin and thyrotropin-producing pituitary adenomas. Endocr Pathol 6:125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges S, Sarkar DK 2001 Transforming growth factor-β regulation of estradiol-induced prolactinomas. Front Neuroendocrinol 22:340–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi K, Sarkar DK 2005 Mediation of basic fibroblast growth factor-induced lactotropic cell proliferation by Src-Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase p44/42 signaling. Endocrinology 146:1948–1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D, Melmed S 1997 Pituitary cytokine and growth factor expression and action. Endocr Rev 18:206–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summy JM, Gallick GE 2006 Treatment for advanced tumors: SRC reclaims center stage. Clin Cancer Res 12:1398–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandilands E, Akbarzadeh S, Vecchione A, McEwan DG, Frame MC, Heath JK 2007 Src kinase modulates the activation, transport and signalling dynamics of fibroblast growth factor receptors. EMBO Rep 8:1162–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlotides G, Zitzmann K, Hengge S, Engelhardt D, Stalla GK, Auernhammer CJ 2004 Expression of novel neurotrophin-1/B cell stimulating factor-3 (NNT-1/BSF-3) in murine pituitary folliculostellate TtT/GF cells: pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and vasoactive intestinal peptide-induced stimulation of NNT-1/BSF-3 is mediated by protein kinase A, protein kinase C, and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase1/2 pathways. Endocrinology 145:716–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenacchi G, Giovenali P, Castrioto C, Giangaspero F 2001 Pituicytoma: ultrastructural evidence of a possible origin from folliculo-stellate cells of the adenohypophysis. Ultrastruct Pathol 25:309–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncaroli F, Scheithauer BW, Cenacchi G, Horvath E, Kovacs K, Lloyd RV, Abell-Aleff P, Santi M, Yates AJ 2002 ‘Spindle cell oncocytoma’ of the adenohypophysis: a tumor of folliculostellate cells? Am J Surg Pathol 26:1048–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min HS, Lee SJ, Kim SK, Park SH 2007 Pituitary adenoma with rich folliculo-stellate cells and mucin-producing epithelia arising in a 2-year-old girl. Pathol Int 57:600–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori S, Hayashi N, Fukuoka J, Kurimoto M, Hamada H, Miyajima K, Nagai S, Endo S 2009 Folliculostellate cell tumor in pituitary gland. Neuropathology 29:78–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]