A 72-year-old man with asymptomatic, bilateral, >80% carotid stenoses diagnosed by duplex ultrasound was scheduled for a left carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and a right CEA 2 months later. He underwent in vivo neck magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination 1 week before each scheduled CEA. Carotid plaque specimens were subsequently evaluated with ex vivo MRI and histological analysis.1 Histology sections were coregistered with ex vivo (0.5-mm thick) and in vivo (3-mm thick) MR slices using the carotid bifurcation as a point of reference. All in vivo and ex vivo MRI images were measured in millimeters from the bifurcation. The entire CEA sample (10-mm thick) was sectioned every 0.25 mm. Measurements in all modalities were referenced to the superior edge of the bifurcation. The gross morphology and calcified regions of each MR image were used to confirm registration with histology sections.1

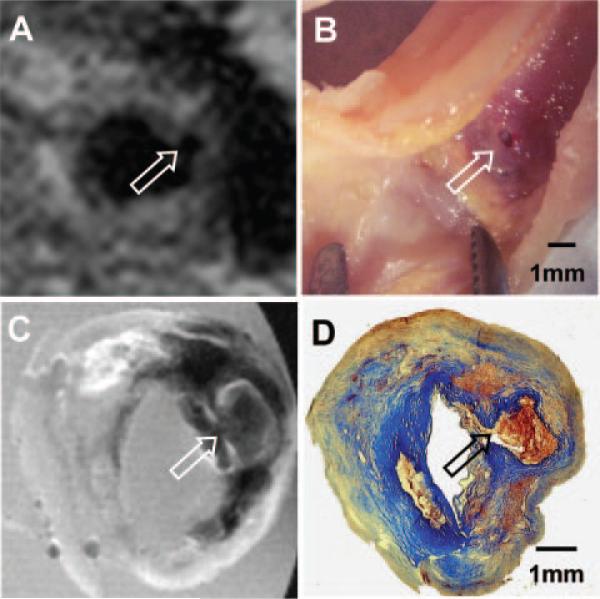

The initial neck MRI performed before the left CEA revealed a small dark region protruding into the plaque from the lumen, a characteristic of plaque ulceration (Figure 1A). An ulcer was visualized at the same location in the ex vivo specimen (Figure 1B). Matched ex vivo MRI of the specimen showed a dark region in T1W consisting of a hemorrhage filling the ulcerated plaque (Figure 1C). Histological analysis revealed intraplaque hemorrhage consisting of fibrin and intact red blood cells (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Plaque ulceration of the left internal carotid artery. A, In vivo T1W MRI at 3T (repetition time, 1 RR of cardiac cycle; echo time, 10 ms; echo train, 9; 1 average and with heart rate of 50 bpm). B, Gross inspection of the CEA specimen. C, Ex vivo T1W MRI at 11.7T of the specimen. D, Trichrome-stained matched histology. Arrows in A through D indicate plaque ulceration and hemorrhage.

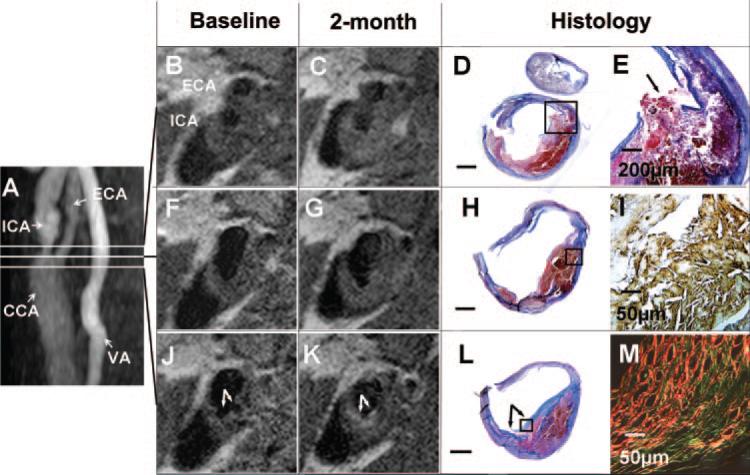

Two months later, a second MR evaluation was performed before the right CEA. A significant signal change was noted in the right common carotid artery (Figure 2J and 2K). The initial MR study revealed a dark lumen with 2 small protrusions suggestive of plaque ulceration (Figure 2J). The second MRI demonstrated a new bright region overlaying the region of ulceration in the right carotid artery (Figure 2K). Subsequent histological analysis of the right CEA specimen showed a collagen-rich fibrous cap (Figure 2L), which corresponds to the bright region in the T1W image (Figure 2K). Histological analysis of the specimen using Sirius red stain under polarized light indicated that the newly formed fibrous cap contained a mixture of type I and III collagen (Figure 2M).

Figure 2.

Healing of plaque ulceration and rupture: serial MRI of the right carotid artery with histology validation. A, Magnetic resonance angiography showing internal (ICA), common (CCA), and external (ECA) carotid arteries and vertebral artery (VA); B, F, and J, Contiguous T1W MRI slices oriented at the lines in A. Plaque ulcerations are detected in the common carotid (arrows in J). C, G, and K, T1W MRI obtained 2 months later at the same location. Comparing to J, a new bright signal band is observed in K (arrows). D, H, and L, Matched histology with trichrome stain (Scale bar=1 mm). Blue-stained collagen-rich fibrous tissue is seen on top of red-stained hemorrhage of L, and it is thin in D and H. E, Fibrous cap disruption in the ICA (arrow, inset box of D). I, Immunostaining of glycophorin A (brown, inset box of H). M, Sirius red stain viewed under polarized light (inset box of L). Collagen type I is red and collagen type III is green.

MRI of the right carotid bulb and the bifurcation showed no significant signal change between the 2 MRI examinations (Figure 2F with 2G and 2B with 2C). Histological analysis demonstrated a heterogeneous juxtaluminal thrombus (Figure 2D and 2H). Immunostaining for glycophorin A revealed a thrombus with numerous cholesterol clefts (Figure 2I), and disruption of a thin fibrous cap was seen in the segment near the bifurcation (Figure 2E).

The presence of plaque ulceration and rupture correlates with increased frequency of neurological events. However, plaque ulceration and rupture occurs in almost one third of asymptomatic patients.2 The healing of silent plaque rupture can contribute to stenosis, but the mechanism and time course of the healing have not been well characterized.2

Here, we report the first case of healing of human carotid plaque ulceration over a short time period. The healed plaque was covered with mainly type I and type III collagen. Depending on the healing phase, healed atherosclerotic plaque could demonstrate proteoglycan-rich mass or collagen-rich scar.2 In general, a healed plaque rupture is associated with the presence of type III collagen, which predominates in the early healing stage and has a green appearance when stained with Sirius red and viewed under polarized light.2 The time course of healing of disrupted atherosclerotic plaques is unclear. Healing of infarcted heart tissue is promoted by initial deposition of type III collagen, followed by type I collagen, which predominates at 3 weeks after myocardial infarction.3 Our observation for the carotid plaque appears to be generally similar. Plaque rupture and healing is dynamic in nature, and noninvasive serial MRI is able to monitor changes in atherosclerotic plaque composition.4 However, no study to date has directly shown the healing of the plaque rupture. We demonstrated a mechanism of healing (growth of new fibrous cap) of the atherosclerotic plaques in vivo by MRI, supported by ex vivo MRI and histology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Donald Small and Jason Viereck for helpful comments.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant PSO HL083801.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Qiao Y, Ronen I, Viereck J, Ruberg FL, Hamilton JA. Identification of atherosclerotic lipid deposits by diffusion-weighted imaging. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1440–1446. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Farb A, Weber DK, Malcom GT, Smialek J, Virmani R. Healed plaque ruptures and sudden coronary death: evidence that subclinical rupture has a role in plaque progression. Circulation. 2001;103:934–940. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes JW, Yamashita H, Waldman LK, Covell JW. Scar remodeling and transmural deformation after infarction in the pig. Circulation. 1994;90:411–420. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu B, Yuan C, Takaya N, Shewchuk JR, Clowes AW, Hatsukami TS. Serial high-spatial-resolution, multisequence magnetic resonance imaging studies identify fibrous cap rupture and penetrating ulcer into carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Circulation. 2006;113:e660–e661. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.567255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]